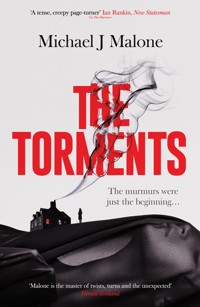

The Murmurs: The most compulsive, chilling gothic thriller you'll read this year… E-Book

Michael J. Malone

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Annie Jackson Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

A young woman starts experiencing terrifying premonitions of people dying, as it becomes clear that a family curse known only as The Murmurs has begun, and a long-forgotten crime is about to be unearthed… `His biggest smash hit yet, an assured paranormal thriller in which the paranormal isn't even the scariest part … A tale that leaves our interest piqued throughout, with the tension and foreboding reaching fever pitch´ Herald Scotland `A tense, creepy page-turner´ Ian Rankin `A master storyteller at the very top of his game, Michael J. Malone weaves the most exquisite tale … mesmeric and suspenseful´ Marion Todd ________________ In the beginning there was fear. White-hot, nerve-shredding fear. Terrifying premonitions of deaths. And then they started… The Murmurs… On the first morning of her new job at Heartfield House, a care home for the elderly, Annie Jackson wakens from a terrifying dream. And when she arrives at the home, she knows that the first old man she meets is going to die. How she knows this is a terrifying mystery, but it is the start of horrifying premonitions … a rekindling of the curse that has trickled through generations of women in her family – a wicked gift known only as 'the murmurs'… With its reappearance comes an old, forgotten fear that is about to grip Annie Jackson. And this time, it will never let go… A compulsive gothic thriller and a spellbinding supernatural mystery about secrets and small communities, about faith, courage and self-preservation, The Murmurs is a startling and compulsive read from one of Scotland's finest authors… ________________ `Poetic and beautifully crafted, this is a chilling and compelling read´ Caro Ramsay `A fine, atmospheric chiller couched in Malone's customary elegant prose´ Douglas Skelton Praise for Michael J Malone `A gothic ghost story and psychological thriller all rolled into one. Brilliantly creepy … a spine-tingling treat´ Daily Record `Prepare to have your marrow well and truly chilled by this deeply creepy Scottish horror … A complex and multi-layered story´ Sunday Mirror `A beautifully written tale, original, engrossing and scary… a dark joy´ The Times `A deeply satisfying read´ Sunday Times `A fine, page-turning thriller´ Daily Mail `Unsettling, multi-layered and expertly paced´ CultureFly

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

On the first morning of her new job at Heartfield House, a care home for the elderly, Annie Jackson wakens from a terrifying dream. And when she arrives at the home, she knows that the first old man she meets is going to die.

How she knows this is a terrifying mystery, but it is the start of horrifying premonitions … a rekindling of the curse that has trickled through generations of women in her family – a wicked gift known only as ‘the murmurs’…

With its reappearance comes an old, forgotten fear that is about to grip Annie Jackson.

And this time, it will never let go…

A compulsive gothic thriller and a spellbinding supernatural mystery about secrets and small communities, about faith, courage and self-preservation, The Murmurs is a startling and compulsive read from one of Scotland’s finest authors.

The Murmurs

Michael J. Malone

‘Not everything that is faced can be changed – but nothing can be changed until it is faced’

—James Baldwin

Contents

Prologue

MOIRA MCLEAN – A MEMOIR

Scottish Highlands 1818

A curse is a difficult thing to master. Like weaving a piece of lace from spider silk, moonbeams and a desperate sense of hope. A pause in the wrong place, words too close together, or spend too long on the utterance of a vowel sound, and you risk the magic shifting, the intention being warped and the target changing.

Such were my learnings at my great-grandmother, Jeannie McLean’s knee, a woman who lived well into her hundreds – a woman who had the power to defy death itself. It was said that Jeannie was the only surviving child of the last witch to be burned in the whole of Ardnamurchan. It was also said she had watched as the local people had dragged her mother, and her older sister and brother, twins Isobel and Andra, from the house towards a smoking pyre. And then she was forced to listen to their pleas for mercy before they were strangled and their bodies thrown onto the flames.

Isobel and Andra, Jeannie told me, had blue eyes, white-blond hair and a beauty unmatched in the country. In the days before the murmurs started, they were tall, slim and strong.

How could children be so beautiful, people asked? How could they be so clever? For they were both well ahead of their peers in the local school.

They had good, kind hearts, Jeannie asserted, but they had no need of anyone else, such was their connection. And there lay the seed of their destruction.

It was unnatural, the local gossips opined. A boy and girl, related, being so independent of everyone else. They had to be up to something ungodly. They had to be giving in to their most base desires. Why else would they be so indifferent and different to everyone else?

And so the sullen stares became whispers. Hands that had curved over mouths to hide evil conjecture became pointed fingers. Unease grew into a murmuring that wouldn’t fade, and suspicion followed them like their own personal haar.

First, it was the turnip crop that failed. Then the oats.

Every ship sent out into the Sound of Mull returned without landing a single fish.

A lamb was born with two heads.

A white-tailed eagle swooped and snatched a child from its mother’s arms.

That was nonsense of course, Jeannie said. Who’d ever heard of an eagle doing such a thing? But repeat a lie often enough and it becomes as solid and as unwieldy as fact, she added.

It’s a sad truth that the gossip was led by people from our own family – and who else, these self-anointed judges opined, but the McLean twins could make such things happen?

Fire and prayer were the answer.

Fire would cleanse, and prayer would see that the land and sea would turn back to health and prosperity.

And if the twins had to be sent back to hell, so would the wretch who gave them life.

The pain of it all had settled in Jeannie’s eyes and informed every look, every gesture. And so, as soon as she was able, she’d relocated to this glen, away from the clan that had treated her and hers so abominably.

Jeannie paused in the telling, her eyes gleaming with the light from the fireplace. ‘Of course, they had no idea how wrong they were.’ Satisfaction warred with something else in her expression. Another emotion I had difficulty naming, at first. Could it have been humility? ‘The twins didn’t have the gift.’ She paused and looked deep into my eyes as if searching for something. ‘I did. And you have it too, I’m sure.’

I felt fear burrow into my heart. ‘I do?’

‘Don’t fret, child. I’ll teach you how to use it wisely. For the good of your family.’ Her eyes narrowed. ‘And to protect you from the sanctimonious.’ She grabbed my hand with the power and strength of someone much lesser in years. ‘But I shall teach you and you will be wise to it all.’

And here and now, the past had come back to hurt me and mine, and I was desperately glad that Jeannie was long dead and unable to see what had become of her sanctuary.

Having lived a life almost as long in years and pain as the fabled Jeannie, I sneaked back up to the village of Anlochard – carried the last five hundred yards on the strong back of my great-nephew Archie. Now I was knee-deep in the waters of a near-frozen stream that ran through the village down to Loch Suinart, with loam under my fingernails, my white hair loose around my shoulders, and a crown of sage and rosemary on my head.

Pain, Jeannie had warned me, was the key to an efficacious spell. Emotional or physical. Preferably both. Hence, the bone-seeping chill of the river that ran past our erstwhile homes.

With a barely stifled sob and a heart near breaking I took one look over my shoulder at the homes that had housed my family for generations. Flames still licked at the sky from the timber and thatched roofs lit by the factor and his men after they had thrown me and mine out onto the cold moor and destroyed everything we owned.

It was happening all over the country, I knew: lands being cleared of humans for the more profitable sheep and lambs. But I also knew that in our case the motivation wasn’t that simple.

A sin other than greed was our undoing, and it came from family – the same family line that pointed the finger and accused poor Jean, Isobel and Andra around a hundred years ago, and that made the betrayal cleave even more deeply through my soul.

Head thrown back, arms wide, throat bare, and eyes staring sightless at the countless stars, I threw words in the old tongue into the night sky. Words of power and meaning. Words that fired my mouth as they slipped out into the frigid air.

Words scour, they scald, they lacerate, they leach into the deepest recesses of the mind. They shame. They rob of you the will to live, and to love.

The words I hurled into the night sky were such words. I prayed that they had the ability to reach into the future, causing more harm than any mere fire or sword. The woman I targeted, it was her and hers that set off the whispering – the murmurs that started the agony for my family. And maddening, agonising, unceasing murmurs would be the instrument of my revenge.

Chapter 1

Annie – Now

She was underwater. The world reaching her ears through a muffle, gurgle and splash.

At first, it was nice. The water just how she liked it. She was on her own. No annoying sibling or parents demanding anything.

Then.

Pressure and a weight on her head.

Strong.

Firm.

Determined pressure.

She kicked furiously. Screamed, ‘Help!’ But as she opened her mouth it filled with water. She spat it out. Panic sparked bright, increasing her need for oxygen.

Desperately trying to scream while not taking in any more water.

‘Help.’

Shaking her head, fighting to get away from the pressure. Fighting to get a hold of the fingers holding her head. Struggling to get purchase that would help her push up out of the water. But her heels slipped furiously against the floor of the bath.

And no matter how much she fought, and struggled, and screamed, she was stuck. Always stuck.

Lungs desperate for air.

Breathe, breathe, BREATHE. But she couldn’t open her mouth because it would fill with water again.

In silent desperation she pretended she’d drowned. Went limp. Waited for the hand to move. Then she could shoot up out of the water onto dry land.

But the pressure never let up.

Until, blessed relief, she shot up from her pillow, hair sweat-plastered to her forehead and her quilt wrapped so tightly around her legs it took several moments to get free.

That Annie had the dream on the night before the next big change in her life, having not had it for a long time, made her query her choices. Was she doing the right thing? Going for the right job? Was the dream some kind of warning?

‘Did I nearly drown as a kid?’ she’d asked her brother Lewis after the first dozen times the dream visited her.

‘Pff,’ he snorted. ‘I can barely remember what I had for dinner last night, and you expect me to remember something like that?’

‘Godssake,’ she countered. ‘Surely you’d remember something like your favourite sister nearly dying?’

‘Only sister.’ He grinned.

‘Well, what the hell is this dream all about then?’

If she’d had parents, she could have asked them, but they both died when she was in her teens. Her mother in a car accident – that she was also supposedly in; no memory of that either – and her father ten months later, of a broken heart.

‘Great that he loved his wife, and all that,’ she’d said to Lewis during a teenage Buckfast session in the local park. ‘But suicide? Really? Couldn’t he have loved his kids a wee bit more? Save us having to live with those losers.’

Those ‘losers’ were the McEvoys, childhood friends of their father – church elders, who applied to adopt them when their father died, to save them going into the system. A fact that Mrs McEvoy reminded Annie of after every teenage huff.

They were good people, Annie was able to freely acknowledge when she grew up, realising that her petty rebellion was a complication of her grief and anger at being left so young without parents. They could have had so much worse, and Mrs McEvoy had become a friend to her now, as an adult.

As she finally shook off her duvet and sat on the edge of the bed, ready to get up, her phone pinged an alert. It was said lady wishing her good luck on the first day of her new job.

Teenage rebellion had not only led Annie to distrust her carers – and get her belly-button pierced – it had fuelled her anger and a resolution that she didn’t want to take an active part in the world. Consequently, education was for stiffs, and work was for the enslaved. And while Lewis got himself a good degree and a well-paid job, as an accountant, for God’s sake, she huffed and puffed from one arts course to another. She was self-aware enough to know that she needed to keep busy, and doing something in art would satisfy that need without kowtowing to The Man and becoming a good little sheep.

But whether she agreed with it or not, she was living in a material world, and that meant she had to have some stuff – like a roof over her head, some clothes, and possibly even a television. And that meant earning a living. Selling tie-dyed T-shirts and leggings from a stall was not going to bring in enough to give her independence; that required regular income, and that meant an actual job.

Mrs Mac – as she now affectionately called her – had advanced her a small loan against future earnings, meaning that for the first time Annie could rent a place of her own.

‘It’s not that we want rid of you, dear … ’ Mrs Mac said while all but wringing her hands against the thought that Annie might feel unloved.

‘But it is time to grow up,’ Mr Mac said with his trademark gruff honesty. An honesty that was always delivered with a half-grin and a twinkle in his grey-blue eyes. Such was his charm, Annie had always felt unable to be offended by the man, even as she railed against his wife.

What neither of them said was that it was time she grew up, like her brother. And she appreciated that. All through her school years that was the attempt at encouragement her teachers had thrown at her. They were twins for goodness’ sake, how could they be so different? He was a top student and athlete. If he wasn’t her brother she would have hated him.

That the McEvoys realised this and never compared the two siblings was one of the reasons why Annie grew to love them.

Annie looked down at her phone, at the message from Mrs Mac wishing her good luck, and with a little lift in her heart replied with a simple thank-you – and:

Feeling a wee bit of first-day nerves, tbh.

Mrs Mac came straight back with:

You worked for this – you deserve it – now go and do what you were born for. Love you, doll.

She wasn’t one for displays of affection, but Annie pictured Mrs Mac in her living room right then, among her china ornaments and doilies, wiping away a tear as she typed out the message on her new tablet, and then doing that thing she did every time her emotions threatened to spill over. A little cough, a shake of her head and an upward tilt of her chin, as if that was enough to reset her brain.

Annie fetched her breakfast, and while she spooned cereal into her mouth she watched the TV news.

An item snagged her attention. A man and woman stood side by side, in the background a small hotel, and beyond that a glimpse of mountain and loch.

‘It’s been fifteen years,’ the woman said, her expression an essay in grief.

Annie stilled her spoon and bit her lip.

‘She just disappeared,’ the man said as he put an arm over the woman’s shoulder. ‘Surely somebody out there knows something.’ In response the woman moved even closer to the man.

Annie noticed the woman was holding a framed photograph of a teenage girl. She held it up and the camera zoomed in on it while the mother spoke.

‘We’ve never given up hope that our girl is still alive,’ she said. ‘If you’re watching this, honey, come home. Please. Come home.’

That face, Annie thought; it was so familiar. Who was that girl, and how did Annie know her? She became aware of a pressure just behind her right eye. Pain built and bloomed across her forehead. She screwed her eyes tight. Not today, please. Not today.

She looked at the screen again, diving into memory and finding nothing. Who was that girl, and why did Annie suddenly feel certain that her parents’ prayers would never be answered?

Chapter 2

Annie – Now

All the way to her new job, Annie couldn’t stop thinking about the girl in the photo, and the unending grief her parents must face. Five minutes into her journey she fished her phone out of her bag and searched for the story. The news channel she’d been watching had a page given over to it.

Mossgow, it said, was a small town in the Scottish Highlands and a scene of a possible tragedy…

Annie’s heart gave a twist. Mossgow. That was where she, apparently, grew up, but she had little recollection of the place. The accident with her mother had wiped almost everything from her memory, although the landscape behind the girl’s parents did stir something in her mind. She scrolled through the article, hoping that if she read it a few times it might unravel more solid memories. But nothing more presented itself.

God, that poor girl. Her poor parents. To have lived with that for fifteen years and still be functional. Annie guessed that it was the hope that kept them going, but again, somehow she knew, or could sense, that there simply wouldn’t be a positive outcome.

She realised her stop was next, and putting her phone back in her bag with a mental promise to phone Lewis and pick his brain, she stood and shuffled towards the door.

When the bus stopped, she jumped off and made her way up the hill to Heartgrove House, arriving only slightly out of breath and warmed through from the climb. It was a modern, red-brick, two-floor structure with large windows and a high sloping roof. Despite the builders’ best attempts at softening the look with a large, curved drive and plenty of trees and shrubs, the purpose of the place was evident in the safety doors and signage. This was a functional building and no amount of dressing up was going to offer a disguise. It was a care home for the elderly. The fact that current Annie was determined to work in this sector would have had teenage Annie squirming with disbelief.

The lobby was full of large-leafed plants, eighties-style red-and-yellow wallpaper, a small reception desk and a row of chairs against the wall, which gave a view out of the glass door and down the driveway.

Sitting there, a chair’s space apart, were two old men. They both looked past Annie and down the hill as if they were losing patience with whoever was going to visit them.

One had a particularly lost expression on his face. He was wearing a light-blue cardigan over a vanilla-coloured shirt, with grey trousers. His face was well lined; one eye drooped and shone with fluid, and his hair was sparse and white over a freckled scalp.

‘Morning,’ Annie said to the men.

‘Whit’s guid about it, hen?’ the man she’d been studying asked. ‘I’ll no’ be happy until I’m away wi’ fae this damn place.’

‘Och, you’re an arsehole, Jimmy. The lassie was just trying to be nice,’ the other man said.

Where Jimmy was dimmed with the need to escape, this man was wreathed in smiles. He was wearing similar clothing to the other man, except his cardigan was green. Glasgow’s age-old Celtic and Rangers rivalry evident even in a place like this.

‘Don’t give me your “glass half full” bollocks the day, Steve. I’m no’ in the mood for it,’ Jimmy replied.

Steve looked across at Annie and rolled his eyes. ‘He’s lovely guy really, hen. His son’s late coming to pick him up, so he’s worried he’s no’ getting out the day.’

‘Aye, Steve,’ Jimmy said as he reached down to the floor, moving in increments towards a stick that lay there. ‘Talk about me as if I’m no’ here. That’s how you win friends and influence people, eh?’

A car horn beeped and both men perked up. But Jimmy’s energy quickly faded when he realised it wasn’t for him.

‘’Sake,’ he said under his breath.

Annie heard someone approaching and turned to see Jane Anderson, the woman who’d interviewed her.

‘Morning, Annie, I see you’ve met our star turns, Jimmy and Steve,’ Jane said with the energy that Annie remembered from her interview. An energy that Annie found herself instantly warming to, thinking this would be a woman she could work with. ‘Gents, this is Annie, a new member of our staff.’

‘Hello, darling,’ said Steve with a chuckle. ‘I’m awfy sorry, but Jimmy appears to have got out the twisted-bugger side of the bed this morning.’

Annie thought it was because she’d moved her head too quickly from Jane to Steve, but her head spun. Lights flickered until her vision dimmed altogether. Her head buzzed with pain. Fear twisted in her gut.

She had to leave. She had to get out of here. Her breathing reduced to gulps.

Annie screwed her eyes shut tight, held a hand out to the wall to steady herself.

‘Here, Annie. You alright?’ Steve asked.

‘I’m fine, thanks,’ Annie replied, fighting down her mounting panic. What was going on? What was wrong with her? She closed her eyes and flashed them open again to send Steve a smile of thanks, but with horror she saw that instead of the kindly face she expected there was nothing there but the bleached bones and vacant eyeholes of a skull, and a low hateful voice murmuring in her head that the old man was about to die.

Chapter 3

Then

The light hurt the girl’s eyes. She blinked hard, trying to see where she was. But her head was so sore. And she was tired. So very tired. She could barely focus.

She slept. Woke again. A flash of memory.

She was in a car.

Too fast.

‘Mum!’ she screamed.

A tree loomed. They were approaching it far too quickly.

Mercifully, sleep tugged at her consciousness, pulling her back.

The girl dreamed. A series of confused sensory impressions. Hot water. She was in a bath. Under the water. Pressure on her head. Unable to breathe. She kicked. Her heels drumming against the floor of the bath. She was only small. The person holding her head down so much stronger than she was. Then shouts. Screams. Release, and a deep, lung-filling breath.

Sleep.

And the dream.

But this time the car reached the water. And went under. And the water was cold. So very cold.

‘Mum!’ she screamed again.

A face – with a terrible light in its eyes – changed into a skull.

The girl woke again.

Again, the light. It scoured her eyes, her brain. Sleep tugged, but she fought it. Where was she? Tentatively, she sought feedback from her senses. Her head was on a pillow. Her body was being pressed down onto a mattress. She moved her feet. Her arms. Sheets were tucked in so tight it was like she’d been restrained. Cushioned shoes squeaking on a hard floor. The swish of trousered thighs. Then a kind-faced woman leaned over her. She felt a light touch on her shoulder.

‘You’re back with us, dear.’ The woman sounded pleased. ‘We thought we’d lost you there.’

‘Where…?’ The girl found that the question escaped her lips in a croak.

‘Let me get you a glass of water.’

‘Don’t leave … ’ Panicked, she managed to release an arm from under her covers and reached for the woman. Nurse?

The warm skin on hers was reassuring. Something tangible to help her align her senses. Help her feel this world was real.

‘It’s okay, honey. I’m just here. Getting you some pillows so you can drink without getting the water all over you.’

The light wasn’t so painful now, so the girl swivelled her head round to follow the progress of the nurse. Who moved to the side and returned, as promised, with a couple of pillows.

‘Here’ she said before carefully propping the girl up in the bed, just enough to slide the pillows under her head and shoulders.

Head elevated now, she groaned as pain shot in.

‘You’re our little miracle.’ The nurse beamed. ‘Just some bruising, as far as we can tell,’ she added. ‘You’re going to be just fine.’

The girl detected something unspoken in the nurse’s tone. Someone else was not so fortunate?

‘Who…?’

Out of sight, she heard more movement. Someone approaching in a rush.

A man. His face tight with anguish and concern.

‘You’re alive,’ he said. Strangely, his voice was familiar, but his face wasn’t. ‘We thought you were dead too.’ He reached the bed, and pulled the girl into his arms, his body convulsing with movements that were like hiccups.

Too. The word rang in her mind like the pealing of a bell.

Body limp in his arms and mind ablaze with confusion, the girl watched the show as if removed from herself. She sent a mute plea for help over the man’s shoulder towards the nurse. She had no idea who he was. But strangely, the one thing she knew was her name. Four syllables announcing her identity.

She was Annie Jackson.

Chapter 4

Annie – Now

Annie was on a seat in her new boss’s office. Jane offered her a drink of water. Everything was coming at her through a dissociative fog, as if her senses were somehow coated in cotton wool.

‘You really have taken a funny turn,’ Jane said. ‘Perhaps you should go home, Annie. You don’t look well.’

‘No, no,’ Annie replied. She shook her head. And immediately regretted it as pain lanced through. ‘I’ll be fine,’ she groaned, holding a hand to her forehead. She had no idea if she would be fine. Ever again. What on earth happened? The old man’s face had changed into a skull right in front of her eyes. Her head was bursting with the pain that had begun at the same time as the vision – or whatever it was. But what she was trying hardest to ignore was the voice that sounded in her mind at the same time.

He’s going to have a massive stroke, it murmured. If he doesn’t get help quickly he’ll die.

Then, in her mind’s eye, like a lost reel from a movie, she’d watched the old man in a room, wearing pyjamas and stumbling towards a door. The door was ajar, and beyond it Annie could make out the white porcelain curve of a sink, topped by a mirror. The man reached out desperately. For what, Annie couldn’t tell. Then he was on the floor, mouth open, eyes staring.

A stroke. The old man was going to have a stroke, and she knew this with the same certainty she knew how to breathe.

What the hell was going on?

‘Is Steve okay?’ she managed to ask, squinting against the pain that was drilling into a point between her eyes.

‘He’ll outlive us all, that man … ’ Jane’s answer clearly one of habit. ‘Why are you asking? Did he say something?’

‘No,’ Annie replied. ‘No. It’s just … ’ How could she say what she’d seen? They’d rush her out of the door and tell her never to come back. They’d think she was deranged. ‘Sorry. This sudden headache … I’ve never had anything like this before.’ She took a long, slow breath, marshalling her resources. She couldn’t afford to mess up. Not on her first day on the job.

‘That drink of water,’ Annie said, ‘and a couple of paracetamol, and I’ll be right as rain.’

Jane looked relieved, and as if she was allowing herself to be persuaded. ‘We are a bit short today. Holidays and all that. And we never really recovered staffing levels after the pandemic. So if you’re sure you’ll be okay?’

‘I’ll be completely fine.’ Annie worked a smile onto her face. Opened her eyes wide, hoping that would sell the lie. ‘See. I’m better already.’

‘Excellent,’ Jane replied. All bustle now, she got up from behind her desk and made for a door just off to her left that Annie somehow knew was to the bathroom.

‘My office is being redecorated, so I’m using one of the bedrooms for the moment,’ Jane said when she returned, as if she’d read the question in Annie’s eyes. She handed Annie a glass.

‘Thank you.’

Annie sipped, trying to disguise her discomfort. A sudden chill enveloped her entire body. She recognised this room, yet she’d never been in it. She hadn’t been in any of the bedrooms, but she knew this was the double of the one she’d ‘seen’ as she’d watched in her mind’s eye while Steve clutched at his arm, collapsed and fell to the ground.

Chapter 5

Annie – Now

Gradually, by attempting to focus on what was in front of her, Annie managed to get control of herself.

Sandra was the other woman on the shift and was asked to show her the ‘tea and toast’ ropes. She was about the same age as Annie, and at a guess she was around six feet tall, had no chest or hips to speak of and had her long, black hair pulled tight to the back of her neck in a ponytail. The hairstyle served to exaggerate Sandra’s sharp chin and cheekbones, and Annie got the impression that Sandra couldn’t have cared less.

Annie fancied that the other woman sized her up in a milli second. The line of her mouth sagged with disappointment.

‘Where have you worked before then?’ Sandra asked.

‘Here and there,’ Annie answered brightly, refusing to show Sandra that she was put off by her tone. ‘A few shops and cafés. Mostly retail.’

‘Mostly retail.’ Sandra’s eyes joined her mouth in a sag. ‘At least you’ll be used to being on your feet all day.’

Then she turned and started walking away along the corridor. ‘The kitchen’s this way,’ she announced over her shoulder.

Another woman in the same uniform was already hard at work in the kitchen. She turned to face them when she heard their approach.

‘Hiya,’ she said and gave a little wave. ‘I’m Joy.’

She was a small woman, arranged as if from a composite of parts. Her face and upper body were tight and wiry, but her hips were wide enough to almost fill the doorway at her back. Her white hair was cut short and her eyes were circled with enough kohl to bleed into her wrinkles.

Sandra stepped away. ‘Can I leave you with Joy … while I go and…?’ Without explaining what she was about to do she left.

‘Right.’ Joy clapped her hands. ‘You’re about to make yourself very popular. Our ladies and gents love their elevenses, so they do.’ She swept a hand across the ranks of brown cupboards, double sink, tall aluminium urn and a machine that looked like one of those toasters provided at a buffet breakfast in a hotel. ‘Everything you need is here. We just need to fill the trolley with cups and saucers, load up the industrial toaster behind me, get the urn boiling and we can serve up.’

As soon as they entered the Sun Room, a large conservatory full of soft chairs and coffee tables, all heads turned to face them. There was an audible ‘ooo’ when those waiting realised there was a new member of staff in the room.

‘Everyone,’ Joy said, ‘this is Annie. She’s new, so be gentle with her.’

A round of soft laughter, and then voices that ranged from the querulous to the brisk sounded out.

‘Hello rerr, Annie.’

‘Welcome, dear.’

Annie felt a hand in hers. Looked down to see a woman in a purple cardigan propped up with a number of cushions. Her hand was so light that Annie felt it was almost imaginary.

‘You look just like my grand-daughter, Lucy. Lovely girl.’ The woman paused. ‘Frances,’ the woman added, holding a trembling hand to the middle of her chest.

‘Frances likes milky tea,’ Joy said with a little edge, suggesting to Annie that they didn’t have enough time to pause over every resident.

Soon it was time to set up for lunch, and after that had been served it was not long before they had to get things ready for afternoon tea and visiting time. And after that, dinner. It felt like Annie’s whole day had been taken up by doling out food and drink. How tragic, she thought, that for many of these people the highlight of their day, every day, was to be served teas and coffees.

One old lady stood out. Her skin was remarkably smooth, her white hair lacquered into place, bright-red lipstick lining her smile, and her eyes were shining. She was wearing a light-blue twinset with pearls and a navy skirt. Thin limbs folded into her chair, she looked lost among the cushions, but her head was up as if ready for a photo shoot. There was a frailty to her that had Annie annoyed at the waste of her own youth. She wanted nothing more than to sit with the woman and listen to her story. To validate a life well lived.

‘Welcome to the nut house,’ the lady said to her, the glint in her eyes suggesting that though the body was struggling with the effects of old age, her mind was as sharp as ever. ‘My name’s Margaret.’

Instinctively, Annie reached forward and lightly touched the back of Margaret’s hand. ‘Enjoy your tea,’ she said before moving on to the next person.

What frustrations must this woman be feeling? Like everyone else here, she may have had a career, or businesses, or organised her family, thrown herself into hobbies – and done the multitude of things we do as we try and live a fulfilled life. But here she was, the best part of her day spent with a hand out, waiting for a hot drink to be placed in it. Nothing on the horizon but a long, silent prayer for a quick and peaceful death.

Back in the staff room, standing with her coat on, ready to go home, Annie was a mess of indecision. What on earth she should do about Steve? All day, she hadn’t been able to rid her mind of the image of him on the floor in his bedroom. But if she told anyone what she knew, or thought she knew, she’d be carted off to the nearest psych ward.

Another thought occurred to her. This place was essentially an end-of-life station. Would Steve be the only one, or would she get more of these visions?

Just thinking of it, and that strange voice in her head, her heart began to race, and her hands were sweating. God forbid that she’d spend the next few years seeing things like that and knowing when and how people were going to die. It would drive her crazy.

Upstairs, after having checked at reception for his room number, she exited the lift, took a left and walked down the corridor until she located Steve’s room.

She placed her head to the wood and paused to listen. The faint burble of a familiar theme tune sounded from the other side of the door. Steve liked his soaps then, she thought. Would he want to be interrupted?

Annie took a step back. What was she doing? The old man would think she was crazy. Was she crazy?

She was certainly beginning to worry that might indeed be the case, but there was no shaking her certainty. If she did nothing, Steve would die.

Chapter 6

Annie – Then

Just a few days before the accident that was to change her life forever, Annie was in the back garden chatting with her best friend and neighbour, Danni. They always met up after school at the far end of the garden, under the wild cherry tree that grew there. Cross-legged on the grass, their conversation would invariably begin with: ‘I hate this place.’ Danni usually said it, and ‘this place’ referred to Mossgow, a town a couple of hours south-west of Fort William on the banks of Loch Suinart. Annie guessed that most preteens who lived in similar-sized places in the Highlands of Scotland would rather be anywhere there might be bright lights and more interesting people, but the kids of Mossgow were doubly troubled, because the place held a church of historic importance and a religious community, meaning adherence to the rules of said church were strictly observed and a complete kill-joy.

‘I’m telling you. It’s like we’re living in a cult,’ Danni said, eyes large.

Annie made a dismissive noise, Danni was always going on about cults. As far as she could understand it, the area was selling itself as a place of religious retreat and hoping that would attract visitors.

‘Well, anyway.’ Danni tossed her hair. ‘It’s like they want us to die of boredom before we grow up,’ Danni said. ‘Save on having all those teen pregnancies.’ The girls shared a giggle. ‘I have a cousin in Edinburgh,’ Danni said, for the millionth time, ‘and she has an actual computer and a TV in her room. She watches TV for hours, and says I have to get Destiny’s Child’s new album.’

A voice cried out into the garden.

‘Danni. Mum says it’s time to come in and do your homework.’

It was her brother, Chris. He and Annie had exchanged a small kiss the previous night. Her first kiss, and she hadn’t yet managed to talk to Danni about it.

Danni read her reaction and smiled knowingly. ‘Well?’ she asked.

‘What?’

Danni laughed. ‘Don’t play the innocent with me. He’s my brother. He tells me everything.’ She tossed her head. ‘Well, not everything, because that would be gross. But … ’ she stared into Annie’s eyes ‘…is my brother a good kisser?’

Annie felt her face heat. ‘It was okay.’

In truth it was better than okay. It was thrilling, embarrassing, fraught with feelings of failure and the possible promise of an exciting time. Her head had been so full of conflicting thoughts since, she worried they might drive her out of her mind.

She leaned forward and asked, ‘What did Chris say?’

‘Danni,’ Chris shouted. ‘Dad’s home.’ Annie could hear a warning there: Danni needed to comply, there and then, and go back into her house.

Danni sighed and looked to the sky. ‘You can tell me about it later.’ She winked, then she jumped to her feet and without a word clambered over the fence that separated their gardens, something she did with such ease, it scandalised her church-elder father, Dennis Jenkins.

Next it was Annie’s turn. A voice from her back door. ‘Kids?’ Annie’s mother.

Her mother was out of bed? She often took what she called her ‘turns’ and stayed in bed for weeks at a time. Annie wasn’t stupid. She’d heard about depression and was sure that was the source of her mother’s intermittent incapacity.

Her mother was standing, arms crossed, just outside the back door; there was something in her stance that sent a shiver of warning through Annie. Something was wrong.

‘Annie!’ her mother repeated. ‘Lewis!’ she called to Annie’s twin brother, who was playing keepie-uppie with a football.

She and Lewis raced to the back door. Everything, or almost everything, they did was in competition. They charged inside and made for the sink. Lewis stopped so abruptly that Annie ran into the back of him.

‘Ouch,’ he complained.

‘Idiot,’ she replied.

‘Kids,’ their mother said. Annie turned to her, recognising the strain in her voice. ‘I want you to meet someone.’

By the door to the hall stood their father, wearing the same tight smile as their mother, and beside him stood a woman. She was like a slightly older version of their mother. Same height and build. Same face but with more lines, and a light in her eye that was almost completely missing from their mother’s.

‘Meet your aunt Sheila,’ their father said, a forced brightness in his voice.

Annie and Lewis looked at each other. A look that asked: we have an aunt Sheila?

Chapter 7

Annie – Then

They were in the dining room. Mother and Father at either end of the table, Lewis and Annie to their mother’s left, and Aunt Sheila facing them.

The table was heavy with food, as if her mother was keen to show off to her sister that she had made a success of her life. See: the food I can provide at the drop of a hat. There were dishes high with mashed potato, green beans, carrots, corn, French fries, chicken wings, sausages, burgers. Annie knew her mother had raided the chest freezer. Meat was a rare treat in their house, usually only served on Sundays, or hot summer’s days when her father took a notion for a barbeque.

Without waiting for the command to begin eating, Lewis’s arm hand shot out as he helped himself to the sausages. They were his favourite and Annie knew he wanted to make sure he got the most.

‘Lewis,’ Dad chided. His eyes shot to the cross on the wall. ‘You know we wait to say grace.’

Lewis sighed.

Annie nudged him with her elbow. Snorted in appreciation of her brother being publicly reproached.

‘Say grace, please, Annie,’ Mum asked.

Annie looked from her mother to her father. Then to her aunt, who was smiling across at her. But the smile halted, became stuck as if there was a shadow lurking behind it.

‘She looks like her.’ Sheila stared at Annie, nodding her head. ‘Mum would have been so pleased.’

Like who? Annie wanted to ask, but the words were frozen by her certainty that her mother wouldn’t want the question answered.

She instinctively liked her aunt. She was like her mother, but softer. Life for this woman wouldn’t be about absolutes, she was certain.

‘Grace, please, Annie?’ Mum said.

Stifling a sigh, Annie ducked her head and recited the prayer by rote.

‘Always so fast,’ Mum said when she’d finished. ‘Try to show some genuine appreciation at your good fortune.’ She made a slow waving movement with her hand across the food.

‘Kids,’ Sheila said. ‘Always with an empty belly.’ She laughed. A sound Annie rarely heard from her parents. ‘To be fair, it does all look delicious. Thank you for inviting me to stay for dinner.’

‘It is good to see you, Sheila, after all this time, but some kind of warning would have been nice,’ Mum replied, and Annie could read a guardedness there. Just what had gone on between these two, and why had Sheila never been mentioned to them? Annie was desperate to ask, but felt, strongly, that she couldn’t.

‘You’re right,’ Sheila said. ‘I shouldn’t have imposed on you like this, but I was worried. We didn’t exactly part on the best of terms.’

Annie watched as her mother inhaled and corrected her posture so that she was sitting perfectly straight. Her head had a slight tilt to the left. A challenge. She didn’t like something about Sheila’s statement.

‘You did a good thing, Ellie,’ Sheila added, a note of affirmation in her voice. ‘The Christian thing. I’m grateful for that, and I’m not here to cause a fuss.’

Annie exchanged a quick look with Lewis. What on earth was happening here? She couldn’t shake the thought that it involved her and Lewis.

And ‘Ellie’. Annie had never heard her mother being called anything but Eleanor. It brought another version to her mind; of her mother as a young girl, jeans dirty at the knee, face smudged. Where that image came from she had no idea, because that was far from the version she’d known all her life. Her mother rarely had a hair out of place, and Annie was sure she had an invisible shield around her that any particle of dirt wouldn’t dare cross.

‘Have you left the army then, Sheila?’ Annie heard her mother ask, and even to her it felt like a clumsy attempt to change the subject. Nonetheless, it was very cool that her aunt had been in the army. It meant she’d got to see a lot of the world. Most of the people she knew had barely left Mossgow.

‘You wanted a fresh start.’ Sheila bluntly bypassed her sister’s conversational thread. ‘You wanted to protect … them … ’ Sheila inclined her head in the direction of the children. ‘And I get that. But there are other people involved.’

‘Not now, Sheila. Please,’ Eleanor replied. Annie recognised that firmness of tone and waited to see how her aunt Sheila might respond.

‘Try the chicken, Sheila,’ Dad said, with a look to his wife. ‘Same butcher. And the … ’

Whatever her father said next was lost to Annie. The room spun. Sounds stuttered. Lights flashed at the back of her eyes.

She shook her head. Shut her eyes. Opened them again.

What was that?

‘You okay, Annie?’ Sheila asked.

‘Yes … I’m … ’ Annie looked towards her aunt. But the woman speaking was no longer there. Annie’s vision shifted. Light fluttered furiously. Her aunt’s face wavered. Lines crossing it as if Annie was viewing her through a broken screen. Her face reformed, and Annie could see through the skin and muscle and veins to the bones of her skull. A voice began in her head, its words unintelligible, strung together without pause. A harrying, urgent voice, the sibilant ‘S’ loudest of all, linking the words like the long coil of a serpent. The face shook again, and then the benign version of her aunt once again looked back. Her eyes full of concern, and a certain knowing.

Annie gasped. Fear a charge under her skin. What was happening to her? She scanned the other faces in the room. They were all completely normal, and all of them were looking at her with worry.

Pain pierced Annie’s head as if she’d been speared, right through the space between her eyebrows.

‘You okay?’ Aunt Sheila asked again, her voice softened with tenderness.

Through the stream of words issuing in Annie’s mind, one word was more prominent. Two syllables. A diagnosis. A word of dread. A word that even she knew, as a preteen, was one to shrink from.

And she just knew, somehow, that it was true.

Annie made herself look up, across the table at Sheila, and spoke with terrible certainty. ‘That’s why you’ve come. You’ve got cancer.’

Chapter 8

Annie – Now

Resolve strengthened, she raised her hand and knocked on Steve’s door. She heard him call something, then his footsteps. Swithering at the wisdom of her approach, she took a step back. Turned to walk away. The door opened.

‘Annie, isn’t it?’ Steve asked, his face warm with a smile of surprise. ‘What can I do for you, hen?’

‘I just wanted to check in on you before I go home.’ Feeling unable to explain why, Annie took another step back, her eyes darting to his shoulders, feet, the carpet at his feet, anywhere but at his face. What was she doing?

Annie forced herself to glance up, and directly into his face. She gasped. Turned away. Then realising his face was normal she looked back into his eyes. They were framed with concern. ‘You okay, Annie? Want to come in for a wee blether?’ He opened the door a little wider.

Annie could see the TV in the background. It had been paused on the face of a well-known actor in a long-running TV series.

‘Sorry. You’re watching your programme. I’ll just … ’

‘Don’t be daft. It’s not often I get visited by a lovely young woman.’ He stepped back, and then stopped. ‘You don’t mind that all the old codgers around here will be gossiping about us?’ He laughed. ‘’Mon in and have a seat.’

Annie stepped inside and sat down in one of the armchairs positioned either side of the TV.

‘What’s on your mind, doll?’ Steve asked as he sat too. He raised an eyebrow. ‘And I mean what’s really on your mind?’

Annie cringed at her stupidity. Steve might be old but he wasn’t daft, and he could clearly see that she was hiding something.

She met his gaze and wondered how much, if anything, she should say. She scanned the room and recognised all of the items from her vision. What she’d seen as the bathroom door was shut.

Something about the directness of his look snagged in her mind. She considered his almost military bearing. There was something about Steve that reminded her of the few cops she met in her life.

‘You weren’t in the police were you?’ she asked.

‘Why? Has there been a murder?’ he laughed. ‘Aye. Did my full service, hen. I guess it leaves its mark on you, eh?’

His answer made Annie consider carefully what she was going to say next. She opened her mouth to speak.

‘Here,’ Steve said. ‘Has there been a murder?’

‘No,’ Annie replied. ‘It’s just … I got this feeling when I met you this morning … ’ God. She was going to sound like a fool. She reviewed the vision she’d had. The bathroom door had been open. The sink in full view. On a shelf above it were some items.

‘I’ve never been in this room, right?’ she asked.

‘Far as I know,’ Steve replied as he sat back in his chair.

‘That’s your bathroom door, yeah?’

‘What’s this about, Annie?’

‘Humour me. Please.’ Annie leaned forward, hoping the earnestness in her face would convince him to bear with her. She closed her eyes and, despite her fear, took herself mentally back to her vision. ‘You have Boots shaving cream and an orange-handled razor on a shelf above the sink. Oh, and a glass with a green-handled toothbrush sticking out of it.’

Steve got to his feet, eyes wide with confusion and alarm. ‘Annie, hen, you need to explain yourself.’

Annie held a hand up. ‘I got this … this impression this morning. I saw you. Here.’ She looked around herself. ‘It was a vision. A warning. Or something. You fell on the way to the bathroom. It was the middle of the night. A stroke.’ Annie felt her fear of the skull face and her worry for Steve mount. ‘And I know, I just … know … if you don’t get immediate help the damage will be so bad you’ll never recover.’ She paused, almost too frightened to say the words, as if casting them into the air might see them pass into truth. ‘And you’ll die.’

Chapter 9

Annie – Then

Annie was on her bed, lying on top of the covers, with a damp cloth over her eyes. Terrified to lift it off because she might see the same skull superimpose itself over her aunt’s face. Because then the voice would come back. That insistent voice full of ill portent and certainty.

Was her aunt really going to die?

Her bedroom door opened.

‘Jeez, you’re a weirdo.’ It was Lewis. She heard his footfall on the carpet as he walked inside, and then she felt the bed give as he climbed on. ‘What was that all about?’

‘Leave me alone,’ Annie demanded. In her mind’s eye she saw him cross-legged, staring at her like she was a strange exhibit at the zoo.

‘Lewis,’ the shout came from downstairs. ‘Don’t be bothering your sister when she has a headache.’

‘That’s not a headache,’ he snorted.

‘Just go, will you?’ Annie said.

There was a moment’s silence.

‘Seriously, though, you okay, sis?’ Lewis asked. ‘That was freaky.’

The concern in his voice was so surprising that Annie pulled the cloth from her eyes and sat up. She groaned as the pain pulsed through her head. Screwing shut her eyes against it she asked Lewis, ‘What did you see? Did you hear anything?’

‘Hear what?’ Lewis asked. ‘You went pure white and stared at Aunt Sheila like she’d just grown a horn out of the middle of her forehead.’

For a moment Annie felt like jumping off the bed and checking herself in the mirror. Maybe that was where the pain was coming from? Maybe she’d grown a horn herself.

‘It was scary,’ she said. Pleading. ‘You’ve got to believe me.’

‘What was?’ Lewis replied. He edged further away from her. ‘You’re freaking me out, Annie.’

‘Aunt Sheila’s face. It became like this … skull. And I heard a horrible voice, and I knew, I just knew, she was going to die.’

‘Fuck,’ Lewis replied.

Annie didn’t know whether to be more shocked at Lewis’s language or the fact that he clearly believed her.

‘Cancer, you said.’

Lewis climbed off the bed as if he was worried that whatever Annie had was catching. He sat in the chair at her desk. Elbows on knees, he leaned towards her. ‘Did you see Aunt Sheila’s face after?’

‘After what? My head was so sore, and Mum was staring at me as if I’d just taken a crap on her favourite piece of china.’

Lewis laughed. A note of joy that rang through her terrified mind and settled it a little.

She reviewed her mother’s face in that moment. Tried to read what her thoughts might have been. No. That wasn’t a look of disgust. It was a look of fear. But mingled with it a terrible truth. And a decision made.

‘The strange thing is … ’ Lewis began. ‘No. One of the strange things is that Aunt Sheila just nodded. She wasn’t weirded out by you at all. It was like none of it – the word popping out of your mouth, the way you were shaking your head – none of it was a surprise to her.’

‘Just leave me alone, Lewis. Please?’

‘It was like … ’ he continued, as he walked to the door. ‘It was like she was expecting it.’ And with that he left.

A few minutes later there was a knock at her door.

‘Leave me alone,’ she groaned.

‘Mind if I come in?’ It was her aunt Sheila.

Annie didn’t reply. She turned over and faced the wall.

Sheila entered her room. Just a couple of steps. In her imagination, Annie could see her standing there, looking around. With that skull face of hers. She shuddered.

‘Nice space you have. I never had a room to myself as a kid. Longed for it, to be sure, but with three girls in a two-bedroom house that was never going to happen.’

Annie sat up so quickly her head spun. ‘There were three of you?’

‘Yes,’ Sheila replied, her mouth settling into a line of sympathy. ‘Your mother’s been keeping you in the dark, eh?’

‘What else hasn’t she told me?’ Annie replied, looking everywhere but at her aunt’s face.

‘Is it okay now?’ Sheila asked. ‘The voice? Has it gone?’

Annie shot a glance up at Sheila, prepared to look away just as fast. But, with relief, she noted it was just her new aunt Sheila looking back at her.

‘Do you know what’s happening to me, Aunt Sheila?’ she asked. ‘And why did I not know I had an aunt? Two aunts?’

‘Your mother had her reasons,’ Sheila replied. ‘It’s not for me to say.’

The door behind her opened wider and her mother came in.

‘No, it isn’t, Sheila,’ Eleanor said.

Sheila squared up to her sister. ‘She needs to know, Ellie.’

Annie watched as her mother’s face grew pale and her mouth tightened. ‘And she will. When the time is right.’

Please don’t talk about me as if I’m not here, Annie wanted to say, but instead she just stared at these two women, these sisters.

‘I wanted to see them. Just once. Before … ’ Sheila began.

‘Well, you have. And now you need to go.’ Eleanor pushed her chin out, but not before Annie read a stab of pain and concern in her mother’s face.

‘But Ellie,’ Sheila said, holding her hands out. Almost pleading. ‘She needs to know.’

‘I’ll be the judge of that,’ Eleanor replied.

‘Yes,’ Sheila said quietly. ‘You always were good at that. Judging.’

The two sisters looked at each other for a long moment. A library of secrets weighted in that look.

‘Just go,’ Eleanor said.

Sheila stepped across the room to Annie and then did something the adults in Annie’s life rarely did: she leaned forward and hugged her.

‘What we don’t understand scares us,’ Sheila whispered. ‘Learn,’ she urged. ‘Try to understand. Only then will you be able to work with the family gift.’

‘Gift?’ Eleanor said so loudly it made Annie jump. ‘How dare you. It’s a damned curse. Leave us, Sheila. Leave us and never come back.’

Sheila held up a hand. ‘Okay. Okay,’ she said.

Then she stepped closer to her sister and pulled her into a hug. But Eleanor’s hands were limp by her side, as if the hug was the price she had to pay for her sister leaving.

When Sheila stepped back her smile took in both Eleanor and Annie.

‘Regardless, it was lovely to see you again, Ellie. And Annie, you’re going to grow into a wonderful human being.’ Her eyes were shiny with suppressed tears. Then, without another word, she turned and left the room.

Once she was gone, Annie’s mother visibly relaxed.

‘What’s going on, Mum?’ Annie asked. ‘Why didn’t I know you had two sisters? Why are you telling her to leave already? It feels like I don’t even know you anymore.’

‘I care for you, Annie Jackson,’ Eleanor said, and Annie in all her twelve years had never seen her mother look so vulnerable. ‘Please understand: I’ve only ever done what I’ve done to protect you. To try and keep you safe.’

For a long while after her mother left the room, Annie tried to puzzle through everything that had occurred – everything she’d just learned – and couldn’t help but wonder who her mother really was.

With a sigh of exasperation, she threw herself back onto her pillow. And regretted the movement when pain bloomed once again between her eyes.

She placed her forearm over her face, squeezed her eyes shut, and considered her mother’s words.

‘I care for you, Annie Jackson,’ she’d said. Care for you.

Not love.

Care.

Chapter 10

Annie – Now