Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Quiller

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

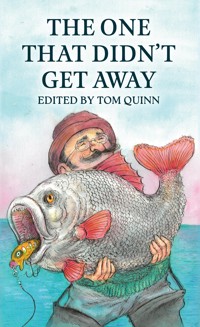

The One That Didn't Get Away celebrates the triumphant days and victorious moments for game, coarse and sea anglers from the past two centuries. Following Tom Quinn's previous book Great Angling Disasters, he has compiled this collection of archive articles and extracts, which captures the excitement, skill and satisfaction of successful angling expeditions. Taking readers from rivers to seas and all points of the compass, this is a wonderful chronicle filled with the highlights of fishing. Anglers will find much here to entertain and delight them – and to remind them why the next best thing to fishing is reading about it!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © 2024 Tom Quinn

First published in the UK in 2024 by Quiller, an imprint of Amberley Publishing Ltd

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-84689-401-5 (HARDBACK)ISBN 978-1-84689-402-2 (e-BOOK)

The right of Tom Quinn to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the Publisher, who also disclaims any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Cover illustration by John Holder

Typesetting by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India.Printed in Malta

Quiller

An imprint of Amberley Publishing Ltd

The Hill, Merrywalks, Stroud, GL5 4EP

Tel: 01453 847800

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.quillerpublishing.com

As soon as you think of fishing you think of things that don’t belong to the modern world. The very idea of sitting all day under a willow tree beside a quiet pool – and being able to find a quiet pool to sit beside – belongs to a time before the war, before radio, before aeroplanes …

George Orwell, Coming Up for Air

The trout within yon wimpling burnGlides swift, a silver dart,And, safe beneath the shady thorn,Defies the angler’s art.

James Tayler, Fly Fishing, 1888

You that fish for dace and roches,Carpes or tenches, bonus noches,Thou wast borne between two dishes,When the fryday signe was fishes.

Anon

Contents

INTRODUCTION

1HIGH DAYS AND HOLIDAYS

Big Fish, Tiny Fly

A Beauty from a Ditch!

A Carp on Roach Tackle

Brazilian Fishing Dog

If They Don’t Sleep, They Rises to the Top of the Water: Battles with Mister Conger

When the Boulder Came to Life

Two Big Salmon on One Cast

An Honest Fly-Taker – the Sprightly Dace

Remembrance of Things Past

Battle Royal – and a Trout Against all the Odds

Twelve-Hour Battle with a Salmon

The Impossible Fish and the Bluebottle

Light Hold on a Thames Giant

The Ghostly Twin

A Gathering of Giant Pike

Mixed Bag to Beat …

2AGAINST THE ODDS

Barbel Landed on a Single Horsehair

Beginner’s Luck and a Novice Sea Trout

A Whopper in the Weir

Thames Miracle

Salmon on Horsehair and Hazel

Nothing Goes Right and Then Nothing Goes Wrong

The Last of the Thames Trout

A Hopeless Chance …

Right up to the Wire

The Duck-Eating Golden Pike

Three Wild Days in Wessex

Christmas Chubbing

Just When all Seemed Lost

The Most Provoking Loch …

An Eel Takes a Trout Fly

3SHOW-STOPPING … AND HEART-STOPPING

Two on at Once

What a Battle was This …

Not Quite Impossible

A Record for the Eden

Freaks Fresh from the Sea …

Herrings Caught on the Fly

Thankless Task

Salmon on the Vicar’s Side!

A Tench Caught on a Fly

Definitely an Undeserved Fish

An Ancient Fish from the Dark

A Giant Pike Lost … and Then Landed

The Biter Bit …

4PLEASURES OF THE FISH

Lucky Angler … Very Unlucky Salmon

Specimens in the Old Canal

Salmon Fishing – Much too Easy!

Salmon Enchanted Evening

Fought by Firelight – a Fifty-Pounder from the Wye

Joey the Impossible Trout, and the Importance of Half-Truths

Pike on Bacon

Slack-Line Beetling

Almost too Easy!

Brook Trout in the Jungle

Mad, Mad Mayfly

A Carp Takes to the Air

5GLORY DAYS

Floods and Storm – and a Fine Fish

Battle of a Lifetime

Betrayed by a Reel

A Grumpy Gillie on the Dee

Fish from a Ruined Swim

Tied and Tangled

Everything Comes to Him who Waits

Fly Fishing with a Spinning Rod

Bass Gone Mad

Never Such Luck Again

New Rod, First Salmon

Better Wild Than Stocked

Introduction

WE – BY which I mean anglers – are a curious bunch. We love to tell tales of the one that got away – the thirty-pound salmon that made a last, mad rush and cut the line on a rock, the huge tench that threw the hook just as it neared the landing net – but we neglect those happier days when the sun shines and we can hardly put a foot wrong.

Of course, the disastrous days are never entirely disastrous because at the very least they whet the appetite for another day by lakeside or riverbank; and we return to fishing each time more determined because each and every outing could be that glorious red-letter day when everything goes to plan and that fish of a lifetime does not get away.

The One That Didn’t Get Away celebrates these red-letter days – and for the vast majority of Britain’s near one million anglers there are always red-letter days. They may not come thick and fast and they may not involve a fish that breaks all the records, but we have all known the supreme excitement, the joy even, of landing a fish beyond all expectation.

And it was ever thus which is why I have trawled through a vast archive of reports from contemporary sources as well as from long-forgotten angling newspapers and magazines to unearth the most amusing, intriguing and occasionally extraordinary stories of angling at its best – stories that include big fish landed against all the odds on the flimsiest of tackle, monsters netted just when all hope had been lost and wonderful fish brought to the bank in the most unlikely of circumstances.

Whatever your interest in angling, whether you are a game fisher, coarse or sea angler, you will find much here to entertain and to delight – and to remind you why the next best thing to fishing is reading about it!

Chapter 1

HIGH DAYS AND HOLIDAYS

Big Fish, Tiny Fly

THE UPPER part of the back stream at Kimbridge joined the Mottisfont water then rented by our old friends, Foster and Alexander Mortimore.

They asked us to fix a date to come over and have a turn in their water, and the only available day was June 7th. Foster Mortimore wrote to us in a day or two that he was afraid we should be full late as there were few fresh flies hatching. However, we decided to go and chance it.

The rods at Mottisfont that day were the two brothers Mortimore, John Day, Marryat, and myself. On our arrival we found the meadows, and even the railway line, covered with spent gnats, and clouds of males were dancing in the air.

There had been very few sub-imagines hatching on the 6th and at our host’s suggestion we decided to try all the wide carriers that held fish.

I do not think we saw a single green drake, and these big fish were as shy as possible, having been fished hard for many days, and a large proportion of them hooked and lost.

Occasionally the female imagines would be seen laying their eggs, and at intervals a fall of spent gnat on the water would bring every fish on the rise.

Presently we had a terrific thunderstorm, and we all took shelter in the station booking office. As soon as it cleared off, we separated, the two Mortimores going downstream, Marryat walking up, and John Day and I having the central part of the water. Day would not fish; he had been hard at it all through the mayfly, and with his usual unselfishness wanted to see me get a big one.

In one of the carriers, we saw the head of a huge trout come up and take a spent gnat. I was on my knees in a moment, crawled up in position and waited for the next rise. This is always a good policy when trout are on spent gnat, as they invariably travel and are dreadfully shy. Up it came again four or five yards higher up, a good underhanded cast landed the fly right at the first attempt, and the fish came with a flop which set my heart beating.

I struck, and upstream went the fish at a great pace. The carrier was full of thick weed beds, and for a time I managed to keep on terms with the trout. At last, it plunged into the thickest part of the vegetation, and worked itself round the weeds until at length it stopped.

In those days we knew nothing of the wonders wrought by slacking a hooked fish, and working it out of the weeds by hand, so I held on and did all I could to move the brute. It was of no avail: Day started off, got hold of a pole and went over to the far side of the carrier and tried to move the weeds apart so that we could get at the trout. The usual result ensued – the trout started, and in a moment broke the gut and was free.

Feeling very downhearted, I tried to persuade Day to have a turn at the next rising fish, but he declined and did his best to console me and held out all sorts of alluring prospects of another bigger fish higher up the same carrier, and just below a brick bridge. On our arrival at this place, sure enough, the fish was on the rise, and after another ineffectual attempt to get Day to fish it, I repaired the damage and put up another spent gnat.

The trout was rising in a small open space below the bridge, and above another fearful tangle of weed.

Using all care and keeping well out of sight, another horizontal cast put the fly on the spot, another bold rise, and I found myself again in another big fish.

I then did what I should have done with the first one, jumped up, and without a moment’s consideration, skull-dragged the trout over the weed bed and started at full pace downstream. After about thirty yards of this the fish shook its head with a savage jerk and tried to turn upstream. I simply stopped it by brute force, and once more started dragging it down as fast as I could go. This was repeated several times, and at last, when we were quite 150 yards below the bridge, the fish made a roll on the water and was netted by Day before it could recover. It was a splendid female and weighed four pounds two ounces.

F. M. Halford, An Angler’s Autobiography, 1903

A Beauty from a Ditch!

VERY WONDERFUL is the perspective of childhood, which can make a small burn seem greater than rivers in afterlife. There was one burn which I knew intimately from its source to the sea. Much of the upper part was wooded, and it was stony and shallow, till within two miles of its mouth. Here there was for a child another world. There were no trees, the bottom of the burn was of mud or sand, and the channel was full of rustling reeds, with open pools of some depth at intervals.

These pools had a fascination for me, there was something about them which kept me excited with expectation of great events, as I lay behind the reeds, peering through them, and watching the line intently. The result of much waiting was generally an eel, or a small flat fish up from the sea; or now and then a small trout, but never for many years one of the monsters which I was sure must inhabit such mysterious pools. At last, one evening, something heavy really did take the worm. The fish kept deep, played round and round the pool and could not be seen, but I remember shouting to a companion at a little distance, that I had hooked a trout of one pound, and being conscious from the tone of his reply that he didn’t in the least believe me, for a trout of one pound was in those days our very utmost limit of legitimate expectation. But soon it lay on the bank – a beauty from little more than a ditch.

Lord Grey of Falloden, Fly Fishing, 1899

A Carp on Roach Tackle

FOR PRACTICAL purposes there are big carp and small carp. The latter you may sometimes hope to catch without too great a strain on your capabilities. The former – well, men have been known to catch them, and there are just a few anglers who have caught a good many.

I myself have caught one, and I will make bold to repeat the tale of the adventure as it was told in The Field newspaper of July 1, 1911.

The narrative contains most of what I know concerning the capture of big carp. The most important thing in it is the value which it shows to reside in a modicum of good luck.

So far as my experience goes, it is certain that good luck is the most vital part of the equipment of him who would seek to slay big carp . . .

And so to my story. I had intended to begin it in a much more subtle fashion, and only by slow degrees to divulge the purport of it, delaying the finale as long as possible, until it should burst upon a bewildered world like the last crashing bars of the 1812 Overture.

Now that a considerable section of the daily press has taken cognisance of the event, it is no good my delaying the modest confession that I have caught a large carp. It is true. But it is a slight exaggeration to state that the said carp was decorated with a golden ring bearing a rare inscription of some sort.

Nor was it the weightiest carp ever taken. Nor was it the weightiest carp of the present season. Nor was it the weightiest carp of June 24. Nor did I deserve it. But enough of negation. Let me turn to the story which will explain the whole of it.

To begin with, I very nearly did not go at all because it rained furiously most of the morning. To continue, towards noon the face of the heavens showed signs of clearness and my mind swiftly made itself up that I would go after all. I carefully disentangled the sturdy rod and the strong line, the hooks, and the other matters which had been prepared the evening before, and started armed with roach tackle. The loss of half a day had told me that it was vain to think of big carp. You cannot of course fish for big carp in half a day. It takes a month.

I mention these things by way of explaining why I had never before caught a really big carp, and also why I do not deserve one now. As I have said, I took with me to Cheshunt Lower Reservoir roach tackle, a tin of small worms, and intention to try for perch, with just a faint hope of tench. The natural condition of the water is weed, the accumulated growth of long years. When I visited it for the first time some eight years ago, I could see nothing but weed, and that was in mid-winter. Now, however, the Highbury Anglers, who have rented the reservoir, have done wonders towards making it fishable.

A good part of the upper end is clear, and elsewhere there are pitches cut out which make excellent feeding grounds for fish and angling grounds for men. Prospecting, I soon came to the forked sticks, which have a satisfying significance to the groundbaitless angler.

Someone else had been there before, and the newcomer may perchance reap the benefit of another man’s sowing. So, I sat me down on an empty box thoughtfully and began to angle. It is curious how great, in enclosed water especially, is the affinity between small worms and small perch. For two hours I struggled to teach a shoal of small perch that hooks pull them suddenly out of the water.

It was in vain. Izaak Walton must have based his ‘wicked of the world’ illustration on the ways of small perch.

I had returned about twenty and was gloomily observing my float begin to bob again when a cheery voice, that of Mr R. G. Woodruff, behind me, observed that I ought to catch something in that swim. I had certainly fulfilled the obligation; and it dawned on me that he was not speaking of small perch, and then that my rod was resting on the forked stick and myself on the wood box of the Hon. Secretary of the Anglers’ Association. He almost used force to make me stay where I was, but who was I to occupy a place so carefully baited for carp, and what were my insufficient rod and flimsy line that they should offer battle to ten-pounders? Besides, there was tea waiting for me, and I had had enough of small perch.

So I made way for the rightful owner of the pitch, but not before he had given me good store of big lobworms, and also earnest advice to try for carp with them, roach rod or no roach rod. He told me of a terrible battle of the evening before when a monster took his worm in the dark and also his cast and hook. Whether it travelled north or south he could hardly tell in the gloom but it travelled far and successfully. He hoped that after the rain there might be a chance of a fish that evening.

Finally, I was so far persuaded that during tea I looked out a strong cast and a perch hook on fairly stout gut, and soaked them in the teapot till they were stained a light brown. Then, acquiring a loaf of bread by good fortune, I set out to fish. There were plenty of other forked sticks here and there which showed where other members had been fishing, and I finally decided on a pitch at the lower end, which I remembered from the winter as having been the scene of an encounter with a biggish pike that got off after a considerable fight.

There, with a background of trees and bushes, some of whose branches made handling a fourteen-foot rod rather difficult, it is possible to sit quietly and fairly inconspicuous. And there accordingly I sat for three hours and a quarter, watching a float which only moved two or three times when a small perch pulled the tail of the lobworm, and occupying myself otherwise by making pellets of paste and throwing them out as groundbait.

Though fine it was a decidedly cold evening, with a high wind; but this hardly affected the water, which is entirely surrounded by a high bank and a belt of trees. Nor was there much to occupy the attention except when some great fish would roll over in the weeds far out, obviously one of the big carp, but a hundred yards away. An occasional moorhen and a few rings made by small roach were the only signs of life. The black tip of my float about eight yards away, in the dearth of other interests began to have an almost hypnotising influence. A little after half past eight this tip trembled and then disappeared and so intent was I on looking at it that my first thought was a mild wonder as to why it did that. Then the coiled line began to go through the rings, and I realised that here was a bite.

Rod in hand, I waited until the line drew taut, and struck gently.

Then things became confused. It was as though some submarine suddenly shot out into the lake. The water was about six feet deep, and the fish must have been near the bottom, but he made a most impressive wave as he dashed straight into the weeds about twenty yards away, and buried himself in them. And so home, I murmured to myself, or words to that effect, for I saw not the slightest chance of getting a big fish out with a roach rod and fine line. After a little thought, I decided to try hand-lining, as one does for trout, and getting hold of the line – with some difficulty because the trees prevented the rod point going far back – I proceeded to feel for the fish with my hand.

At first there was no response; the anchorage seemed immovable.

Then I thrilled to a movement at the other end of the line which gradually increased until the fish was on the run again, pushing the weeds aside as he went, but carrying a great streamer or two with him on the line. His run ended, as had the first, in another weed patch, and twice after he seemed to have found safety in the same way. Yet each time hand-lining was efficacious, and eventually I got him into the strip of clear water; here the fight was an easier affair, though by no means won.

It took, I suppose, some fifteen or twenty minutes before I saw a big bronze side turn over, and was able to get about half the fish into my absurdly small net. Luckily by this time he had no fight left in him, and I dragged him safely up the bank and fell upon him. What he weighed I had no idea, but I put him at about twelve pounds, with a humble hope that he might be more.

At any rate, he had made a fight that would have been considered very fair in a twelve-pound salmon, the power of his runs being certainly no less and the pace of them quite as great. On the tackle I was using, however, a salmon would have fought longer.

The fish in my net, I was satisfied, packed up my tackle, and went off to see what the other angler had done. So far, he had not had a bite, but he meant to go on as long as he could see, and hoped to meet me at the train. He did not do so, for a very good reason; he was at that moment engaged in a grim battle in the darkness with a fish that proved ultimately to be one ounce heavier than mine, which, weighed on the scales at the keeper’s cottage, was sixteen pounds five ounces. As I owe him my fish, because it was his advice that I put on the strong cast, and the bait was one of his lobworms, he might fairly claim the brace. And he would deserve them, because he is a real carp fisher and has taken great pains to bring about his success. For myself – well, luck attends the undeserving now and then. One of them has the grace to be thankful.

H. T. Sheringham, Coarse Fishing, 1912

Brazilian Fishing Dog

ONE DAY I witnessed a very strange thing, the action of a dog by the waterside. It was evening and the beach was forsaken; cartmen, boatmen, fishermen, all gone, and I was the only idler left on the rocks; but the tide was coming in, rolling quite big waves on to the rocks, and the novel sight of the waves, the freshness, the joy of it, kept me at that spot, standing on one of the outermost rocks not yet washed over by the water.

By and by a gentleman, followed by a big dog, came down to the beach and stood at a distance of forty or fifty yards from me, while the dog bounded forward over the flat, slippery rocks and through pools of water until he came to my side, and sitting on the edge of the rock began gazing intently down at the water.

He was a big, shaggy, round-headed animal, with a greyish coat with some patches of light reddish colour on it; what his breed was I cannot say, but he looked somewhat like a sheepdog or an otterhound. Suddenly he plunged in, quite vanishing from sight, but quickly reappeared with a big shad of about three and a half to four pounds weight in his jaws.

Climbing on to the rock he dropped the fish, which he had not appeared to have injured much, as it began floundering about in an exceedingly lively manner. I was astonished and looked back at the dog’s master; but there he stood in the same place, smoking and paying no attention to what his animal was doing.

Again, the dog plunged in and brought out a second big fish and dropped it on the flat rock, and again and again he dived, until there were five big shads all floundering about on the wet rock and likely soon to be washed back into the water.

The shad is a common fish in the Plata and the best to eat of all its fishes, resembling the salmon in its rich flavour, and is eagerly watched for when it comes up from the sea by the Buenos Aires fishermen, just as our fishermen watch for mackerel on our coasts.

But on this evening the beach was deserted by everyone, watcher included, and the fish came and swarmed along the rocks, and there was no one to catch them – not even some poor hungry idler to pounce and carry off the five fishes the dog had captured. One by one I saw them washed back into the water, and presently the dog, hearing his master whistling him, bounded away.

W. H. Hudson, Far Away and Long Ago, 1918

If They Don’t Sleep, They Rises to the Top of the Water: Battles with Mister Conger

AT LAST, the weather became favourable. We therefore at once determined to go fishing, and see whether, after their long holiday from hook and line the fish would not be in a biting humour.

‘How long shall we be out?’ said the friend who went with me.

‘As long as the fish bite,’ said I, ‘therefore we had better take some food with us, for there are no bakers’ shops by the Spit Buoy, and they don’t sell cheese at the Boyne.’

‘Morning, sir,’ said Barney, the civil and obliging provider of boats on the beach, and whose name was once Barnabas, but who never will be called anything but Barney again. ‘Better have the Laughing Jackass, sir, she’s all ready.’

I have an unfortunate habit of looking after little matters, and knowing that there is a hole, which ought to be stopped up by a cork in the bottom of every boat, I examined it to see if the cork was in its place; of course it was not. We soon got a cork and fastened it in tight, one of our party telling us that he once knew a young man who went out a little way to sea, and who, finding that there was a little water in the bottom of the boat, actually took the cork out of the hole to let the water out, quite forgetting that the water would rush in; it did rush in to his great surprise, and the boat was pretty nearly full before he could get ashore again.

We were soon out on the marks Robinson Crusoe had indicated, and were wondering whether the old man would keep his appointment. At last, we were delighted to see him paddling away out of the harbour. He was soon alongside, his brave old face radiant with smiles, for he had taken a great fancy to me, though he does not to everybody.

‘Are we on the marks, George?’

‘Not by a long ways, sir.’

‘Then just put us right like a good fellow, will you? Better come into our boat; we will tow your old tub astern.’

‘Don’t you go to insult my old boat, sir, or I won’t show you the wrack.’

‘Never mind, George, it’s only a joke.’

‘Let go the anchor, boy,’ said George.

The boy picked it up and spat on it.

‘What’s that for?’ said I.

‘That’s for luck,’ said George. ‘And to make the fish bite; but it don’t always, for a chap the other day spit on his anchor (and it was a brannew one, too) he heaved it overboard; but there was no cable on it so he lost it right off, and was obliged to go home to fetch another, so he lost his anchor and his tide of fish too.’

‘When do you go out fishing most, George?’

‘I don’t fish much of a day, sir; I fishes at night most and almost every night too when it’s anyways like weather. I got no clock nor yet watch; but I’ve got the stars, as will let me know the time to a quarter of an hour. There’s one star in particular as serves me, and in a month’s time I noticed there was never a quarter of an hour’s difference in her time.’

‘Do you ever go to sleep, George?’

‘No, sir. I don’t go to sleep; but I tell you what, sir, I thinks the fish sleep of nights that’s my experience of them. I’ve been out thousands of nights and I’ve always observed as one particular hour is different from any other hour of a night, and that’s between twelve and one.

‘The fish never bites at that time, and after that hour is over they begins again and keeps on till daylight; but before that hour they always fishes slack, and I can sleep between twelve and one if I likes, for it’s no use heaving the line overboard; but after the clock strikes one the fish won’t let me go to sleep and I’ve always found it so.

‘That’s what makes me think the fish sleep; if they don’t sleep they rises to the top of the water. When the water is thick and it’s a moonlight night, that’s the time to catch ’em if the water is thick and it’s dark too, the fish can’t see the bait. They are on the bite, too, of frosty nights. I puts my sail over my head, and it gets as white as a sheet. I often prays for it not to come daylight, for I never feels cold as long as the fish bites, the night is the best time to catch the congers, sir. The congers is as taffety fish as is; there’s not a delicater fish as swims, and they are very nice in their feeding. If a whelk was to get on the bait the conger would never touch it, not if you was to bid at right; they are regular bait robbers them whelks. But when the congers gets on to the hook they lets you know it, and when you pulls them up, they curls their tails and holds a powerful sight of water; it’s ten to one you don’t lose them if you have not got strong gear. But you must have nice fresh bait.

‘If there’s a bone in the bait, they won’t touch it; Master Conger will have the first grab, or none at all. I’ve cut up a dozen pouts, and seen the conger whack at them all, and then he never takes them if they don’t quite suit his taste. The biggest conger as ever I catched was in the grass at the back of the Gosport Hospital. Just as the sun goes down I hooks my gentleman, and says I to the man who was fishing near me: “Joe, I’ve got him this time and no mistake, and a beautiful fish he is!”

‘He towed me and my little boat round my anchor six times, and I got a good Dutch line, so strong that three men could not break it, for we tried it afterwards. Master Conger had got hooked outside of his teeth, still the hook had a good strong hold, but yet it gave him the chance of chawing the line; and he kept on chawing it a good one, so I played him till at last I got him alongside, and tried to haul him, and then he flew right at me out of the water. It was a terrible dark night, and I could hardly see, but I hit him a rap over the head with my stump, and then I was obliged to let him run again, or he would have slewed my arm right off, and pulled me out of the boat as well, for I could not slip my cable. At last, I got terribly tired, and so did Master Conger, for he let me haul him up alongside; Joe then came up with his boat, and we both whipped into him amidships, and jerked him into the boat. When he got aboard I thought he would have knocked my old boat all to pieces, for he was fore and aft in a minute, and sent everything flying. I was only afraid he would get his tail on the gunwale (for congers is terribly strong in the tail) and then he would have hauled himself overboard; so I watched my chance, and hit him a crack just where his life lay, and then he was quiet at last.

‘He was all six foot long and sixteen inches round the thickest part.

‘His great head was like a sheep’s, and his jaws was awful. I sold over four shillings’ worth of him, besides what I ate myself; and all along his backbone was fat, as fine and white as suet.

‘He was a fish he was.’

Frank Buckland, Curiosities of Natural History, 1858

When the Boulder Came to Life

THE THIRD day, in the afternoon, we had our first and only thorough sensation in the shape of a big trout. It came none too soon. The interest had begun to flag. But one big fish a week will do. It is a pinnacle of delight in the angler’s experience that he may well be three days in working up to, and once reached, it is three days down to the old humdrum level again. At least it is with me.

It was a dull, rainy day; the fog rested low upon the mountains, and the time hung heavily on our hands. About three o’clock the rain slackened and we emerged from our den, Joe going to look after his horse, which had eaten but little since coming into the woods, the poor creature was so disturbed by the loneliness and the black flies; I, to make preparations for dinner, while my companion lazily took his rod and stepped to the edge of the big pool in front of camp. At the first introductory cast, and when his fly was not fifteen feet from him on the water, there was a lunge and a strike, and apparently the fisherman had hooked a boulder. I was standing a few yards below engaged in washing out the coffee pail, when I heard him call out: ‘I have got him now!’

‘Yes, I see you have,’ said I, noticing his bending pole and moveless line.

‘When I am through I will help you get loose.’

‘No, but I’m not joking,’ he said. ‘I have got a big fish.’ I looked up again, but saw no reason to change my impression and kept on with my work.

It is proper to say that my companion was a novice at fly fishing, he never having cast a fly until this trip.

Again he called out to me, but deceived by his coolness and nonchalant tones, and by the lethargy of the fish, I gave little heed. I knew very well that if I had struck a fish that held me down in that way I should have been going through a regular war dance on that circle of boulder-tips, and should have scared the game into activity, if the hook had failed to wake him up. But as the farce continued, I drew nearer.

‘Does that look like a stone or a log?’ said my friend, pointing to his quivering line, slowly cutting the current up toward the centre of the pool.

My scepticism vanished in an instant, and I could hardly keep my place on the top of the rock.

‘I can feel him breathe,’ said the now warming fisherman, ‘just feel of that pole.’

I put my eager hand upon the butt and could easily imagine I felt the throb or pant of something alive down there in the black depths.

But whatever it was it moved like a turtle. My companion was praying to hear his reel spin, but it gave out now and then only a few hesitating clicks. Still the situation was excitingly dramatic, and we were all actors. I rushed for the landing net, but being unable to find it, shouted desperately for Joe, who came hurrying back, excited before he had learned what the matter was.

The net had been left at the lake below, and must be had with the greatest dispatch.