Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

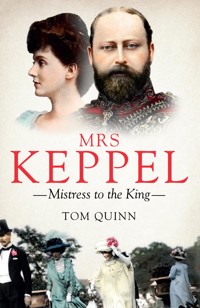

For Alice Keppel, it was all about appearances. Her precepts were those of the English upper classes: discretion, manners and charm. Nothing else mattered - especially when it came to her infamous affair with King Edward VII. As the King's favourite mistress up until his death in 1910, Alice held significant influence at court and over Edward himself. But it wasn't just Edward she courted: throughout her life, Alice enthusiastically embarked on affairs with bankers, MPs, peers - anybody who could elevate her standing and pay the right price. She was a shrewd courtesan, and her charisma and voracity ensured her both power and money, combined as they were with an aptitude for manipulation. Drawing on a range of sources, including salacious first-hand eyewitness accounts, bestselling author Tom Quinn paints an extraordinary picture of the Edwardian aristocracy, and traces the lives of royal mistresses down to Alice's great-granddaughter, the current Duchess of Cornwall. Both intriguing and astonishing, this is an unadulterated glimpse into a hidden world of scandal, decadence and debauchery.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 349

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MRS KEPPEL

— Mistress to the King —

Tom Quinn

‘More knowledge may be gained of a man’s real character by a short conversation with one of his servants than from a formal and studied narrative begun with his pedigree and ended with his funeral.’ —SAMUEL JOHNSON, THE RAMBLER

‘Alice Keppel had the sexual morals of an alley cat.’ —VICTORIA GLENDINNING

‘She [Alice Keppel] has had her fists in the moneybags these fifty years…’ —VIRGINIA WOOLF’S DIARY

Contents

Prelude: Then and Now

ABOVE ALL THINGS Alice Keppel loved money and position, and it was these loves that motivated her to climb the social ladder into the highly lucrative position of the King’s favourite mistress. Three generations later, Alice’s great-granddaughter, Camilla Parker Bowles, followed in her footsteps when she became the lover of Charles, Prince of Wales, at catastrophic cost to Charles’s marriage to Lady Diana Spencer.

Camilla Shand, as she then was, grew up in an atmosphere in which affairs were treated much as her great-grandmother Alice Keppel’s circle treated them: they were private matters with no moral aspect at all. And thus when Camilla said to Charles in 1970, ‘My great-grandmother was the mistress of your great-great-grandfather, so how about it?’ she no doubt simply thought this was carrying on an exciting upper-class tradition; a tradition that says morality, like taxes, is for little people.

Camilla’s affair with Charles continued before, during and after his marriage to Diana Spencer, and Camilla even helped Charles buy Highgrove House, still his home today, because it was close to the house she shared with her husband. It was a shrewd move of which Camilla’s great-grandmother would have approved.

Knowing that as a divorced woman she would not be allowed to marry Charles, Camilla advised him to marry Lady Diana Spencer. The perception was that Diana was timid, easily led and therefore unlikely to make a fuss when she discovered that Charles had no intention of giving up his mistress.

Diana was to become Charles’s ‘brood mare’, just as Queen Alexandra had been his great-great-grandfather’s brood mare. Camilla played the role of her own great-grandmother Alice Keppel, who was described at the time as a key figure in Edward VII’s ‘loose box’.

Camilla’s affair with Charles was aided and abetted by an upper-class set that, in its attitudes and morals, is largely unchanged since Edwardian times. It’s a world closed to outsiders with its own rules and its own fierce desire to protect those on the inside. It relies heavily on the deference paid to it by politicians and the governing classes. It is the set centred on a few dozen large country estates still privately owned by ancient families. Social mobility via great wealth allows no admittance to this world even today – foreigners are still seen as outsiders just as the Cassels and Rothschilds were seen as outsiders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

It was this group of aristocrats, a group that overlaps with those who helped Lord Lucan on the night he killed the family nanny, that enabled Charles and Camilla to pursue their affair by meeting each other at the country houses of their friends; friends who would never dream of letting anyone outside their circle know what was going on. They would have known, too, about the plan to find Charles a complacent wife. Then and now they live as their ancestors lived a century ago. The only difference is that the broughams and phaetons have become Range Rovers and Bentleys.

These are families who find it absurd that there are still people in the world who live on less than half a million a year; they laugh at the idea that there are people who have to buy their own furniture (rather than inheriting it) or cook their own food. They still defer to the royals and believe the rules that apply to the wider world do not apply to them, and since they can say and do as they please because their livelihoods are never at stake, their lives are very much like those lived by Edward VII, Alice Keppel and their friends a century and more ago.

Mocked by the media as a world of Tims who are nice but Dim, the English upper classes, though diminished in number, were until recently supported on their landed estates by vast subsidies – effectively state handouts – from the European Union. These largely made up for incomes lost to taxes and death duties in the early twentieth century – taxes that were fiercely resisted by the then Prince of Wales and his circle.

Charles and Camilla received these subsidies (and despite the recent Brexit vote will continue to receive them for some time) even though they are enormously wealthy anyway. Any concerns they may have had about Britain’s so-called loss of sovereignty in the EU were more than compensated for by these state handouts. They helped ensure that Charles did not have to befriend financiers as his great-great-grandfather was forced to do; they helped instead to ensure that Charles and Camilla were and are able to live the opulent lives lived by both their ancestors. And as Alice Keppel, the subject of this book, knew: ‘Love is all very well, but money is better.’

Introduction

BOOKS ABOUT EDWARDVII and his circle return again and again to the same sources. These typically include papers held by the British royal family and other European royal families along with documents held in official or government archives. Many of these books make a point of thanking the royal family for allowing access to various official papers and this is almost certainly a sign that these books will have little genuinely new to tell us. This applies particularly to books about Queen Victoria and her son Edward VII because so much has deliberately been destroyed – what’s left can be seen because it is usually innocuous.

Edward VII’s life was so scandalous – numerous mistresses and perhaps half a dozen illegitimate children – that we can be sure the royal family has done as much as possible to conceal or destroy the most incriminating evidence. We know, for example, that Edward VII himself insisted all his personal papers and letters be destroyed after his death. This was, no doubt, partly due to the fact that the papers included painful memories recorded during his extremely unhappy childhood. But mostly the document bonfires that lasted for several days after the King died were part of a comprehensive effort to protect his reputation.

Alice Keppel became the Prince of Wales’s mistress in 1898 and she remained his favourite mistress from then until his death in 1910. Alice got into bed with Bertie, as Edward was known to his friends, at the first opportunity because she wanted money and he had vast amounts of it. But Bertie was by no means the first wealthy man Alice had slept with for money. Almost from the day she married the Hon. George Keppel in 1891 she knew that she wanted to live among the very richest in the country and as her husband did not have the kind of money she needed, she was determined to get it by the only means open to her: the sale of her body to much wealthier men than her husband.

What makes the story particularly shocking is that Alice’s husband was only too happy to live on the money Alice earned by sleeping with the King, various aristocrats and numerous bank managers.

Alice and George had two children, but, as this book will show, neither was fathered by Alice’s husband. Both children were illegitimate and one, Sonia, is the grandmother of the present Duchess of Cornwall, the former Camilla Parker Bowles, now wife of Charles, Prince of Wales. It is very possible – and indeed believed by many – that Sonia was fathered by Edward VII, Charles’s own great-great-grandfather. This would make the Duchess of Cornwall a blood relation of her husband, albeit distantly.

Alice Keppel’s affair with the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, damaged the King’s relationship with Queen Alexandra; Alice Keppel’s great-granddaughter Camilla Parker Bowles’s adulterous relationship with Prince Charles destroyed his relationship with his wife, the late Diana, Princess of Wales.

It was always said that Sonia Keppel was the daughter of Alice and George Keppel. By contrast it was a barely concealed secret that Sonia’s elder sister Violet, born six years earlier than Sonia in 1894, was certainly not George Keppel’s daughter. Violet’s father was the MP and banker Ernest William Beckett (1856–1917), later Baron Grimthorpe, with whom Alice Keppel had an affair – in return for money – very soon after marrying the financially inadequate George Keppel.

Violet Keppel was to become notorious for a string of lesbian affairs in the 1920s and beyond, and her parentage became a matter of public speculation as a result. She was well known across fashionable London during her affair with Vita Sackville-West – an affair described in painful detail by West’s son Nigel Nicolson in his book Portrait of a Marriage.

Alice’s second daughter Sonia, by contrast, stayed out of the public eye, partly because she was far more conventional than her sister but also to avoid drawing attention to her dysfunctional family and the very real possibility that she might in fact be the daughter of King Edward VII.

The destruction of Edward VII’s private papers was carried out in accordance with the King’s wishes by his private secretary Francis Knollys. Edward’s long-suffering wife, Queen Alexandra, also insisted on her death that all her papers should be destroyed, and for similar reasons. In Alexandra’s case Charlotte Knollys, Francis’s wife, burnt the papers.

Had the Knollys’s servants behaved as Edward had behaved, the couple would have thrown them out on the street, but the rules were different for a King and Queen – however messy their lives, their reputations must be protected. That at least was, and is, the view of the royal family and their immediate circle.

Embarrassing documents that escaped the fires and might have turned up in succeeding years were also destroyed by a notoriously secretive family understandably embarrassed by the antics of a King who spent most of his life chasing other men’s wives and, when necessary, either bending the law or breaking it to avoid any repercussions for himself.

Edward’s most significant extramarital affair was with Alice Keppel, and this book is the story of her life. I have drawn to a limited extent on published versions of her life as well as official papers and the memoirs of those who knew her and the people around her. I say to a limited extent because memoirs of the time were mostly written by people who shared, to a large extent, Alice’s values and aristocratic background and they therefore had every reason to hide the truth about her. Osbert Sitwell, for example, describes her charm and humour; Princess Alice writes almost as if Alice Keppel were Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Virginia Woolf, a rebel from Victorian and Edwardian values of hypocrisy and deceit, was one of the few to write bluntly about Mrs Keppel. After meeting her at lunch in 1932 Woolf wrote:

I lunched with Raymond [Mortimer] to meet Mrs Keppel; a swarthy, thick set, raddled, direct (‘My dear’ she calls one) old grasper: whose fists have been in the money bags these 50 years: but with boldness: told us how her friends used to steal, in country houses in the time of Ed. 7th. One woman purloined any jewelled bag left lying. And she has a flat in the Ritz; old furniture; &c. I liked her on the surface. I mean the extensive, jolly, brazen surface of the old courtesan; who has lost all bloom; & acquired a kind of cordiality, humour, directness instead. No sensibilities as far as I could see; nor snobberies; immense superficial knowledge, & going off to Berlin to hear Hitler speak. Shabby underdress: magnificent furs: great pearls: a Rolls Royce waiting – going off to visit my old friend the tailor; and so on.

The anglophile American novelist Henry James called Bertie ‘Edward the Caresser’ and he thought his character and relationship with Alice Keppel ‘quite particularly vulgar’.

But we must weigh against this the many statements that recall Alice Keppel’s good qualities – her kindness, for example, at least to her social equals. Harold Acton, famously a member of the Brideshead set at Oxford in the 1920s, later lived in Italy close to where Alice Keppel had her final home. He said of her: ‘She possessed enormous charm, which was not only due to her cleverness and vivacity, but to her generous heart.’

Alice was also the last word in discretion and secrecy; she was, if anything, more secretive even than the royal family. She left no significant papers, and would have been horrified at the idea of writing her memoirs. When in later life she heard of the scandal surrounding Edward and Mrs Simpson, she famously remarked that things had been better done in her day – meaning affairs and sleeping with men for money were fine so long as no one found out or made a fuss if they did. When in 1921 Alice heard that Daisy Brooke, another of Edward VII’s former mistresses, planned to write her memoirs, Alice condemned the idea as a breach of a ‘sacred’ relationship.

I had long wanted to write about Alice Keppel’s life, but it was only in the early 1980s while researching a book on domestic servants that, quite by chance, I met and interviewed at great length a remarkable woman who, from her early teens, had worked as a maid for the Keppels.

Agnes Florence Cook, known to her friends as Flo, was a mine of information about the Keppel household from the late 1890s until 1924 when the Keppels effectively left England for good. Many of Agnes’s tales came down to her from her mother and grandmother, who had also worked for the Keppels. Agnes, who was in her late eighties when I met her, had a remarkably detailed memory of life in the Keppel’s grand London houses seventy and more years earlier, and it is these memories that inform much of this book.

The story Agnes told me was deeply shocking in many ways, revealing as it did that Alice Keppel was prepared to sleep with almost anyone rich enough to make it worth her while and that Camilla Duchess of Cornwall’s grandmother may well have been fathered by Prince Charles’s own great-great-grandfather.

The convention that describes upper-class women who sleep with men for money as ‘mistresses’ seemed to Agnes entirely unfair. A woman from what used to be called the lower orders would always be referred to as a prostitute or a kept woman if she slept with men for money so why did the same or similar labels not attach to more aristocratic women living similar lives? According to Agnes it was another example of one rule for the rich and another for the poor.

Agnes’s memories stayed with her for decades because she felt deeply the injustices of a world where servants were seen as scarcely human. They were expected to devote their lives to the families for whom they worked and for little financial reward. Agnes herself spent more than a decade working fourteen-hour days in the Keppel household for very little money and with only one afternoon off each week. Even this free time was strictly controlled by the family. Talking to servants from other houses was strictly forbidden; boyfriends were strictly forbidden.

Grand houses were built with separate servants’ staircases so the family might have as little contact with the people who looked after them as possible. If by chance Agnes or one of the other lower servants met a member of the family on the main stairs she was instructed to turn to face the wall. Any servant who forgot to do this and made eye contact with a member of the family faced instant dismissal. It was all a far cry from the absurd fiction of television’s Downton Abbey.

Rose Plummer, a friend of Agnes who also worked as a maid in many great London houses in the 1920s, recalled the kind of thing servants had to put up with:

I was on the landing at the right time – that is, when the family should have been elsewhere – dusting away when I heard someone coming up the main stairs. I didn’t have time to dodge into a bedroom or down the back stairs, which is what you were supposed to do, so I just turned to face the wall and, bearing in mind what had happened before when I’d got told off for glancing up, I made sure I kept my eyes on the little flowers on the wallpaper.

Next thing was I felt him stop behind me. He just stopped and I thought, ‘Bloody hell. He’s got stuck. Or he thinks I shouldn’t be here.’

A bit of me wanted to giggle. Then I froze. I felt a hand on my bum. It wasn’t just a light pat. He left his hand there quite gently for a bit then pushed and tried to get his fingers right between my legs.

I had my big apron on and my dress as well as thick stockings – with very attractive thick pads sewn to the knees! – and a giant pair of bloomers made out of cotton as thick as sailcloth, so I knew he wasn’t going to get very far. But I wasn’t really shocked. I didn’t think of it as a sexual assault while it was happening. I didn’t think of anything. I was just surprised by what seemed to be happening.

I think he was disappointed and having shoved a bit more and done some odd noisy breathing he stopped and I heard him go off down the corridor.

This was the grubby underpinning of an aristocratic – and royal – world that wanted society to think it represented the height of moral probity.

There has never been a full biography of Alice Keppel despite the fact that she is one of the most fascinating figures of late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century British history, a figure who personifies the late Victorian and Edwardian era of upper-class decadence and vast social inequality.

Most of the published material refers to Mrs Keppel as the King’s confidante or his maîtress en titre, or as ‘la favourite’. The suggestion is that her position in relation to Edward had a semi-official air about it; that her role was far more than that of sexual partner. It’s as if historians and biographers have been seduced by Alice just as Edward VII was. Biographies of the King all repeat the same clichés about Alice. They emphasise how good she was for Bertie – she kept him in a good temper, she was a conduit for various powerful figures who wished to influence the King, she knew how to soothe and flatter him, she knew how to keep him in temper as no one else could. She is therefore seen in almost every history of the period as a benign influence; as someone who enabled Edward VII to be much better (and better-tempered) than he might otherwise have been.

Royal biographers who trot out the same old stories about Alice’s virtues and good influence on the King tend to forget that flattering and soothing him arguably made him more unreasonable, more difficult to deal with, not less. And the effect of Alice’s constant presence on Queen Alexandra tends to be played down, and little mention is made of the fact that Mrs Keppel was the first to sack any of her servants who she believed to be behaving immorally, even if that ‘immorality’ amounted to no more than having a boyfriend or ‘follower’, to use the jargon of the time.

Alice Keppel always did as she pleased so long as the outward show of respectability was maintained. Her life was underpinned by attitudes that were to destroy her daughter Violet’s chance of happiness, and two generations on, those same attitudes caused the divorce of the present Prince of Wales from his first wife.

Alice could sleep around but the servants could not – this hypocrisy is something Agnes Cook never forgot. The upper-class attitude to servants can perhaps best be seen in Nigel Nicolson’s embarrassed description of his mother Vita Sackville-West stepping over a servant scrubbing the front step of a grand London house as if the poor woman was simply a parcel.

The real life of Alice Keppel lies behind the official versions trotted out by biographers and historians who often suffer from a perhaps unconscious tendency to treat the upper classes with a level of deference they would not afford lesser mortals.

This unacknowledged bias also afflicts those who write about Bertie, as Prince of Wales and later as Edward VII. Certainly his philandering is mentioned and often at length, but the emphasis is always on the fact that despite his womanising, his gross overeating and his almost pathological love of pleasure, he managed to get some work done. Official histories somehow become squeamish at the idea that he was a selfish, idle, bad-tempered, immature man who lost his temper if the whole world did not dance attendance on him. Friends’ wives were expected to sleep with him automatically; aristocratic women such as Mrs Keppel and others were expected to become his mistresses. No one was ever allowed to complain at how they were treated.

Can we really believe that so many women would have slept with this 5ft 7in. man with a 48in. waist who stank of cigars and sweat if he had not been King? The emphasis on his kingly qualities is absurd. He could speak French and German, it is true, and he liked to keep up his continental connections – largely because brothels and gambling were legal in France while they were illegal in Britain – but there was little to his statesmanship beyond that.

The writer A. N. Wilson makes the point that Edward’s diplomatic skills lay not in his abilities but in the fact that he let professional politicians get on with it rather than, like his mother, constantly interfering in areas where he could contribute nothing. It is true that Edward, though quick to anger, could be charming and was often at pains to put lesser mortals at their ease, but as one of his friends commented, ‘he was happy to ignore his own rank so long as no one else did’.

This book starts from the premise that Edward VII really couldn’t be bothered much with work if he could possibly avoid it. His childhood, as we will see, destroyed any interest he might have had in anything beyond enjoying himself in brothels, gambling dens and in the beds of other men’s wives. His bleak early years produced an adult who expected Parliament to provide him with millions of pounds each year (in today’s values) so he could lead a playboy life of tantrums and over-indulgence, hypocrisy and cruelty. He was good to his favourites, but liked occasionally to humiliate them as he did regularly with his friend and fellow rake Sir Christopher Sykes.

An anonymous critic writing in The Clarion in the 1880s implied that Bertie’s mother Queen Victoria would not have had the brains to become a maid if she had not been lucky enough to be born a Princess. Her son was perhaps little better, but then the sort of childhood experiences he endured were never going to produce a well-balanced adult.

Charles I lost his head because he would not accept that the days when monarchs had absolute political power were over. His son Charles II was wiser and therefore devoted his life to pleasure not power, knowing that he could still use his position to ennoble his friends and illegitimate children and make them rich, and to seduce any woman who took his fancy. Bertie was remarkably similar. It’s as if power must find an outlet; monarchs without political power inevitably enjoy wielding personal power.

My main sources for this book are not, as I have said, the usual official histories, nor have I had access to the Keppel family papers, nor indeed to the royal archives. What would be the point? That has all been done before.

The destruction of Edward and Alexandra’s papers may have been a tragedy for historians but the act of destruction itself speaks volumes. There is no doubt Bertie’s letters would have revealed a string of mistresses and casual affairs – including affairs with what were then known as common prostitutes. They would also have revealed that the King interfered on several occasions with the justice system and was utterly ruthless in his treatment of anyone who threatened to expose him. He was supported in this by numerous aristocratic members of the establishment who would have been the first to condemn such behaviour in lesser mortals.

The dark side of Bertie’s life, the side that went up in flames with his papers, can at last be glimpsed through the memories of someone who was there. Someone who lived in the Keppels’ house when Bertie visited, as he did regularly, to have tea and sex with Alice Keppel while her husband was away from home. And Agnes Cook’s memories don’t just relate to life in the Keppel household. They reveal a network of communication between numerous servants working at the Keppel’s various houses over the decades, for despite their employers’ best efforts to prevent their servants gossiping, gossip they did. They managed to communicate with each other, and Agnes’s mother’s servant grapevine included friends below stairs at Bertie’s London home Marlborough House, at Buckingham Palace, Sandringham and the Keppels’ family houses in Norfolk and in Scotland.

The long silence of those destroyed royal papers can now be broken and through Agnes Cook’s first-hand, often eyewitness accounts of those far-off days we get a remarkable glimpse of the real world of Alice and Bertie: a world with no moral compass; a world of hypocrisy and deceit, of criminality and illegitimacy and all in the name of pleasure and money.

Chapter 1

Alice – ‘Not Quite Top Drawer’

ALICE FREDERICA EDMONSTONE came from a family that was always a little too keen to emphasise its ancient lineage and its royal connections. Her male ancestors were almost invariably military men who were often also given ceremonial posts at court that amounted to little more than sinecures.

The earliest record of the family appears to be that of Henricus de Edmoundiston who lived near Edinburgh in the mid-thirteenth century. But the family really sprang from Culloden near Inverness. Here, Duntreath Castle in Strathblane had been given to William Edmonstone by Robert III in the mid-fourteenth century. Edmonstone had married Robert’s daughter Mary, and the castle was a wedding present. This royal connection, however ancient, was one the Edmonstones were always keen to recall.

But by the mid-nineteenth century the family was indistinguishable from any English aristocratic family. After the destruction of Catholic claims to the throne the Scottish aristocracy fell over each other in their haste to seem more English than the English. Their male children were schooled at Eton and Harrow and it was the ultimate disgrace for a member of a family such as the Edmonstones to speak with a Scottish accent.

Alice’s family looked to London and spoke in patrician tones that would sound absurdly clipped by today’s standards, and via marriage for the daughters and commissions in the army for the sons, they expected preferment and lucrative employment as of right.

Many of Alice Edmonstone’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ancestors had also been lawyers and MPs. Sir William Edmonstone, Alice’s father, was born at Hampton in Middlesex, now part of greater London, in 1810. He joined the navy as a young man, served in India and had risen to the rank of rear admiral by 1869 and then full admiral in 1880. From 1874–1880 he was also MP for Stirlingshire.

William married Alice’s mother, Mary Elizabeth Parsons, in 1841. She was the daughter of the British resident of the Greek island of Zakynthos. He was effectively governor of the Ionian islands.

In addition to Duntreath Castle, a vast pile largely rebuilt in the nineteenth century, the Edmonstones had a house in Edinburgh and rented a house each year in London’s Belgravia, but they were not rich by the standards of the aristocrats who dominated London society.

Edward VII was to be the centre of this world and he enjoyed an annual income of roughly £11 million (in today’s values) while the Edmonstone estates produced around £200,000–£300,000 a year in today’s values.

This made the family feel relatively poor, but one should remember a large suburban house on the outskirts of London in 1900 might cost around £1,000 to buy, so aristocratic expectations then as now were high. If landowners and the upper classes have a sense of entitlement today it is nothing to the sense of entitlement felt by the Edmonstones and others like them a century and more ago.

The expectation of preferment at court was a way to augment diminishing rents from land and relatively small amounts of army pay. And the Edmonstones might have been far poorer had they not been able gradually to sell off land to railway companies expanding across Scotland in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Earlier on the family had also sold their Irish estates to make ends meet.

The problem for William Edmonstone was that he had nine children – Alice, born in 1868, was the last – and expected them all to live as the Edmonstones had always lived. But the estates, or what remained of them, could not produce the money to keep the family in the style they felt was their due. The need for good marriages was therefore paramount, but there was a further difficulty. Eight of William Edmonstone’s children were daughters who needed dowries. Had they been sons the situation would have been easier, but the old cultural norms still held sway and daughters were much more expensive to marry off well.

Of course other aristocratic families found themselves in the same position and looked for wealthy marriages for their children. This was why numerous American heiresses – more than seventy between 1880 and 1920 – were able to marry into the increasingly desperate British aristocracy. The aristocracy would have loved to continue to marry only within and across the families they had always married but taxes and the fall in land values made this impossible.

This chink in the armoury of the British class structure was spotted by status-obsessed Americans who had money but no history or titles, so they sent their daughters and sons to London to buy their way into the peerage. And it worked. It was a tradition that to some extent dated back to the eighteenth century – a tradition satirised by Hogarth in his series of paintings Marriage à-la-mode, where an aristocratic family allows a wealthy industrialist to marry into the family in return for money.

This was the background to Alice’s childhood. The family was ancient and well connected but not quite rich and well connected enough. They were also Presbyterians who took a strict view of morality and the rules of behaviour – ironic, given Alice’s future career. In later life Alice’s sisters, who all married clergymen, soldiers or minor landowners, hated even to mention Alice and what they saw as her embarrassingly sordid life.

Agnes Cook recalled that when Alice occasionally visited one of her siblings she would joke about expecting a frosty welcome; she rarely in fact visited any of them with the sole exception of her brother Archie, whom she adored and whose family she supported financially throughout his life. Archie would never have judged his sister since he benefited from her relationship with various wealthy men, especially Edward VII. Indeed, it was Alice who persuaded Edward VII to give Archie a well-paid job as groom-in-waiting in 1907. Needless to say, the job involved almost no work at all. But there is no doubt her other siblings wanted little to do with her. They would have shunned her completely, but as her illicit relationship was by then with the King, they had to stifle their protests.

This was all far in the future when Alice was born in 1868 at Duntreath Castle. Or is that where she was born? The biographers disagree, some insisting she was actually born not in Scotland, but at Woolwich at the naval dockyard where her father was superintendent, a role not unlike that of comptroller of the navy, a job held by Samuel Pepys more than two centuries earlier. Her father was nearly sixty when she was born and had not yet succeeded to the baronetcy – which is why they may have been living at Woolwich rather than at Duntreath. Her mother, Mary Elizabeth, was twenty years younger than her husband, but still decidedly a geriatric mother by the standards of the time.

Alice was the prettiest girl in the family and her nickname was always Freddie after her middle name Frederica. Family legend has it that in her early years she was boisterous, argumentative and very much a tomboy who liked to get her own way. She was also decisive and rather masculine both in appearance and manner. By the time she reached her teens she realised that being a tomboy was frowned upon and she gave it up almost overnight, but her confidence and assurance remained. Her argumentative nature gave way slowly to a curious, steely will combined with charm and good looks; she quickly realised these were the qualities that would get her what she wanted without the need for loud protests. Her daughter Violet recalled her good humour and her lack of malice. Even when she was telling a funny story about someone the story never had a cruel edge. She had a reputation which she retained throughout her life of never being deliberately malicious.

Alice learned to be what we today would call manipulative. She could get people to do as she wished. One of her siblings said:

Freddie suddenly stopped upsetting people with her rowdy behaviour and chose instead a subtle but very firm approach that involved never losing her temper but also never giving up till she had gained her object. She smiled but would brook no opposition and she had that rare skill which involves persuading other people that they want to do what you want them to do.

Life at Duntreath revolved around the unchanging pastimes of the rural aristocracy: riding, shooting and fishing, stalking, large family meals, and the whole edifice supported by numerous servants. Among the children only Alice and Archie seemed to take any interest in these pursuits. Indeed, Archie, who enjoyed painting throughout his life, was remarkably similar to George Keppel, the man Alice was later to marry. Archie disliked rough sports, was quiet, meticulous and unobtrusive. Having been brought up surrounded by girls this was perhaps hardly surprising, but he also deferred to Alice in everything and allowed her to take charge completely of his life as a child and as an adult.

Alice disliked lessons but loved playing outside and already enjoyed male conversation, whether that of her father, the footmen or the stable lads. Like all aristocratic children she was expected to be neither seen nor heard when she was very young, but she had an uncanny ability to charm her father, especially out of his occasional gloomy moods. Her sisters claimed that she manipulated him, but whatever the truth, she was certainly her father’s favourite, and the rules that normally applied to Victorian girls were relaxed for her.

Governesses ran the nursery and the older children’s lives and at most the younger children might expect to be presented to their parents once a day in the early evening, well dressed and carefully coached into saying something intelligent or amusing or both.

Well-born mothers of new infants still packed them off to a wet nurse as the idea that an aristocratic woman would breast-feed her own children was considered probably indecent and certainly disgusting. Queen Victoria herself loathed the whole idea of babies and small children, and in this as in so much else she set the tone for the upper classes of the nineteenth century.

Alice’s great love as a child, and it was a love shared by her favourite sibling Archie, was gardening and flowers and for the rest of her life her various houses were always filled with blooms that she insisted were changed every day. At Duntreath as a child and later in life she and Archie would design and plant out new parts of the garden while the men set off for the hill to shoot stags.

According to family legend a bored twelve-year-old Alice set off one day with her brother Archie and climbed Ben Lomond. Her mother was horrified, feeling this was decidedly unladylike. But then Alice did not aspire to be like her mother, who seems to have been a vague presence obsessed with painting – a love she passed on to only one of her children, Archie.

Every summer the family left Scotland and lived in a rented house in London’s Belgravia.

Agnes Cook recalled the gossip about young Alice among the servants:

Well, the family came to London for what was called the season – girls coming out I mean and visiting all the families they knew. They were looking for suitable husbands even from when the girls were eight or ten and when I say suitable I mean from a very closed circle of families – just a few hundred families ran the whole of London society. Anyway my grandmother and mother told me all the servants used to be amazed that Alice was always playing with the boys while her sisters were much more serious but she had the family boldness and was really much more like a boy. She used to come down to the kitchen where she wasn’t really supposed to come at all, my grandmother said, and ask if there were any cakes. Well there were always cakes or something and she’d have to be answered as if she was her ladyship. My grandmother said that if she fancied something she would just say ‘give me that’, take it and walk off without a word of thanks.

Her sisters were all much older, more like aunts really and far more serious than Alice who had almost nothing to do with them then or thereafter. Her sister Mary married the Lord Advocate of Scotland, another married a major and a third a vicar. They were all worthy but very boring. Alice felt she had little or nothing in common with them. She was determined I think to have a more exciting life; to do better and she had the looks to do it. My grandmother said she was glorious-looking as a young girl.

Mind you, she was still very attractive when I knew her later on. Rumours had it that she used to kiss the stable lads when she was a girl just to see what it was like but I think that was probably said because of how she later behaved – you know, sleeping with the King and all sorts of men who used to come to the house when her husband was away.

By the time she was in her teens Alice’s sisters had all married and left to live in various places across Scotland. That sort of provincial life would never do for the precocious and already ambitious Alice, who longed to be in London and escape the long dreary days in the Highlands.

Like most aristocratic girls in the second half of the nineteenth century Alice received no formal education at all. She read to Archie and he read to her and like all well-born girls she learned to dance and especially enjoyed Scottish reels. She was by all accounts an accomplished dancer, which no doubt stood her in good stead when she visited Balmoral years later with the King.

There was a widespread idea among the upper classes that wellborn men disliked well-educated girls, which is why they were excluded from English public schools and from the old universities. Even when they were finally admitted to Oxford and Cambridge they could not be awarded degrees. Cambridge, for example, only began awarding women degrees after the end of the Second World War. But even the social accomplishments typically expected of a girl of Alice’s class appear to have been largely missing – Alice never spoke French well, unlike her daughter Violet who was a brilliant linguist, and she did not play the piano or paint. But an upbringing that involved learning very little was in some ways considered the correct upbringing for a girl who was expected to marry someone with a title and rich enough to ensure she could spend the rest of her life simply organising lunches and dinner parties.