Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

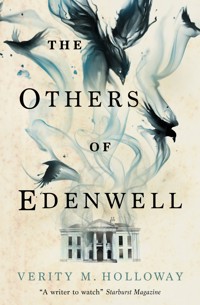

A dark spirit haunts an isolated Norfolk retreat in this unsettling and sinister historical horror set in the early 1900s, perfect for readers of Michelle Paver, Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Andrew Michael Hurley. Norfolk, 1917. Unable to join the army due to a heart condition, Freddie lives and works with his father in the grounds of the Edenwell Hydropathic, a wellness retreat in the Norfolk broads. Preferring the company of birds – who talk to him as one of their own – over the eccentric characters who live in the spa, bathing in its healing waters, Freddie overhears their premonitions of murder. Eustace Moncrieff is a troublemaker, desperate to go to war and leave behind his wealthy family. Shipped to Edenwell by his mother to keep him safe from the horrors of the trenches, he strikes up a friendship with Freddie at the behest of Doctor Chalice, the American owner of the Hydropathic. As the two friends grow closer and grapple with their demons, they discover a body, and something terrifying stalking the woods. The dark halls of the spa are breached, haunted by the woodland beast, and the boys soon realise that they may be the only things standing between this monster and the whole of Edenwell.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 578

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

1942

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“Strange, infinitely sad, and ambiguously haunted, Verity Holloway's new novel is entirely its own creature. Edenwell – a WW1 hydrotherapy retreat surrounded by ominous woodland and the scars of ancient mines – offers a deliciously spooky, folk horror-imbued setting for this Weird meeting of scars and secrets; fans of Lucie McKnight Hardy will be delighted.”

Ally Wilkes, Bram Stoker Award-nominated author of All the White Spaces

“This is a book of gentle strength, which works its magic by luring and inviting, without ever shouting. It will make you forget the world for a while, and then look at it from a new perspective. It is a story with a great sense of time and place, which also manages to be timeless and universal. Call it horror, call it fantasy, call it what you want, as long as you read it.”

Francesco Dimitri, World Fantasy Award winner and author of Never the Wind

“The absolutely convincing recreation of the past combined with a gradual, creeping dread make this a fascinating and frightening book. The prose is accomplished, the characters perfectly realised; rarely has horror been treated with such intelligence and attention to detail. Holloway is a major talent.”

Alex Pheby, author of Mordew

“In The Others of Edenwell, Verity M. Holloway has woven a world of strange and secret treasures. It’s a beautifully written novel that finds its way under your skin and makes a lasting impression.”

A. J. Elwood, author of The Cottingley Cuckoo

“A mesmeric novel. This is such an absorbingly-written book, that I was annoyed with myself that I had read it so quickly.”

Johnny Mains, author of A Man at War

“An uncanny heart beats between the pages of this beautifully crafted book. Beguiling, chilling and profoundly disorientating, something terrifying and ancient stirs in this story of friendship, love and loyalty set against the all-pervading grief and loss of the Great War.”

Lucie McKnight Hardy, author of Water Shall Refuse Them

“Verity M. Holloway makes otherworldly darkness all too real.”

Priya Sharma, author of Ormeshadow and the award-winning collection All the Fabulous Beasts

THE

OTHERS

OF

EDENWELL

VERITY M. HOLLOWAY

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Others of Edenwell

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363950

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363967

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Verity M. Holloway 2023

Verity M. Holloway asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

FOR EDWARD, FRED, AND BILL URRYWHO DIED TOGETHER AT GALLIPOLION THE 12TH OF AUGUST 1915

THERE ARE THREE TYPES OF MEN

Those who hear the call and obey.

Those who delay.

And – The Others.

To which do you belong?

—PARLIAMENTARY RECRUITING COMMITTEE

“In some peculiar way great wars open up fresh channels for the psychic senses, and the physical struggle of great armies appears ever to have its counterpart on the spiritual plane.”

—RALPH SHIRLEY, editor ofThe Occult Review, 1915

PROLOGUE

THERE IS ONE surviving photograph of young Freddie, rescued from the bins of a Thetford charity shop during the 1970s. We glimpse him lined up with the rest of the hospital staff, shrugging against the wind rolling in from the flat Norfolk breckland. The photograph serves as a roll call for that hard year of 1917, when so many orderlies of sound body and mind had crossed the Channel to die. It is, in essence, a ghost image; of a young man on the cusp of a maturity that would never come, but also of a world beyond the frame of frail celluloid. Too much conspicuous absence. Too many women, standing with their backs to the fading grandeur of Edenwell Hydropathic Hotel.

It has been my pleasure these past thirty years to dedicate myself to the study of Alfred Ferry and the trail of breadcrumbs he left behind. Much has been said of the events of May 1917 in that hitherto quiet corner of East Anglia. I prefer to focus on Freddie’s output; his puzzling, beguiling talent.

Surveying his body of work, collected here, what can one expect of the youth himself? Perhaps someone more striking than the figure at the back left of the photograph. Tall-ish, blond-ish, thin yet soft of face, he wears his rifle slung over his shoulder, mirroring his father beside him. These men were not soldiers, but groundsman and son. For young Freddie, there would be no sons. His energies were spent elsewhere, unbeknownst to those closest to him, let alone the art world. So strangely interrupted, so nearly lost.

We believe we know the world in which Alfred Ferry lived. Half blind, we squint into it each November on Armistice Day and convince ourselves we can see. We know the images Freddie left behind, impenetrable and unsettling, intricate and troubling. But we may never know the thoughts in his head. I believe he preferred it this way.

DR FRANCIS BYATT,Norwich Academy of Art and AnthropologyAlfred Ferry: A Centenary of Strange Illusion

ONE

Broken apothecary bottle. Pencil on butcher’s paper, 6×8in. C. February 1917.

Oblong bottle, medicinal type, smashed in two. In the white slash of reflected light, we see a speck. Something is coming.

AJACKDAW WILL TALK in his sleep, but Alfred Ferry made little noise at all.

He dozed, his head wrapped in damp linen like a desert explorer from The Boys’ Realm. The warm bathwater rippled with his breath, and in the dark of his drowsing mind he heard the crows calling.

Out there, in conference without him, they teemed in the pine trees, a raucous Ha! Ha! while gangs of rooks jeered and wheezed, all pipe tobacco and spilled ale. The blue-tinged magpies clattered musically like the man at the Red Lion playing the spoons, and the jackdaws, always bolder, were the first to break through the canopy to survey the Hydropathic. Where is the knave? they were saying. Where is he?

“They’re putting out the breakfast things, Ferry. Get on.”

Nick Scole leaned over the bath as far as his bad leg would allow. Rough fingers clipped Freddie’s nose, and the rooks blew away like coal dust. Freddie pulled the linen from his face and hauled himself upright in the tub. Gooseflesh prickled across his bony shoulders.

The Solarium had no clocks, but the wisteria foaming over the gallery windows was drowsy purple in the February half-light, signalling the late hour. Freddie was permitted to use the baths before the guests were breakfasted, and only on Doctor Chalice’s prescription. Here he could lie with the sun reaching down through the glass roof, the potted ferns bursting green around him and the tiles gleaming like a Mediterranean lagoon. It was a ballroom once, Chalice told him, when Edenwell was a private house, long ago. It was part of his vision to keep the soul of the place intact. That spirit of gentle leisure and pleasure, so good for the body and the mind.

Freddie let his hands break the surface of the water and placed them over his heart. It felt more agreeable, if he wasn’t mistaken.

“You awake?” said Scole. “Better be. When I was twenty-two, I was doing thirteen-hour days at the dairy.”

If the Solarium walls were a lagoon, Nick Scole was an iceberg. His white uniform glowed. Some institutions required their male staff to wear little black dickie-bows, a palate cleanser to the starched tunic and trousers that so nearly said hospital and therefore death. At Edenwell, Doctor Chalice preferred more formal garb, verging on military. It lent the orderlies a most British authority, he said, which Freddie’s father thought was quite astute for an American. As for Scole, the Edenwell tunic and trousers were the closest he would get to a soldier’s kit ever again. The silver Wound Badge shone on his chest. ‘For King and Empire. Services rendered.’ Freddie disliked how often he found himself looking at it, or at the orderly’s shaved cheeks, the texture of shingle. Rendered, the rooks snickered. Like tallow.

“Get dressed,” Scole said. “And wipe up after yourself, else I square you up.”

He lurch-thumped away through the swinging doors and out into the gentlemen’s changing rooms. Beyond that, in the main corridor, the maids could be heard, carrying mounds of white towels and pushing tea trolleys. Freddie could almost smell the breakfast kippers, though the building was judiciously laid out so no rogue odours could ever infiltrate the treatment rooms.

The guests would be stirring. Up in their suites, some availed themselves of the washbasins steaming with Edenwell water and lavender soap, while the wealthier visitors enjoyed private showers or steeled themselves for a morning massage from Katie Healey whose hands could subdue concrete. The fire was being coaxed in the library, the morning papers fanned out, the linen smoothed over the dining room tables. And in the groundskeeper’s cottage, flung out on the edge of Choke Wood, Fa would be hunched at the hearth, preparing his, and Freddie’s rifles.

Time to dry off, put on his overalls, and pretend he had never been there at all.

* * *

The breckland would look underdressed without a monument to the special water coursing beneath the black soil. If a stranger had no idea they were standing on such a remarkable spot, Edenwell Hydropathic commanded respect by virtue of being the only building for miles, bar the odd shepherd’s hut and bramble-bound hunting blind. Visitors had plenty of time to stare at the edifice, square and white and far too large, as they were drawn down the driveway through acres of patchy pines, interrupting the occasional cluster of deer. By the time they reached the front portico with its polished Grecian columns, they had already been treated to a wholly unnecessary jaunt around the four-layered fountain on the front lawn – the Well of Eden, the source of their hopes.

For the staff of Edenwell, Freddie included, the Hydropathic was about a different kind of hope: that of keeping the old girl afloat. Freddie tucked his broom under his arm and fumbled with the gaolers’ ring of keys jangling on his belt. The North Wing had been shut off since a year after the war began. Freddie remembered the day they locked it, draping beds and tables, shutting the windows tight. The staff chatted nervously, filling the silence where once there had been the shuffling of slippers and the ever-present sound of water, pouring, spraying, douching. Doctor Chalice brimmed with optimism that day.

“When all this is over – and it won’t be long, friends, I firmly believe it – what men will want is sanctuary. A little amusement. Imagine thousands of weary English soldiers disembarking at Folkestone, and the first thing they see is a billboard promising a pretty Norfolk nurse pouring a cool glass of healing water. And you and I? We’ll be ready.”

Freddie tucked the memory away, shunting open the door with one shoulder. They closed the North Wing because the lack of men meant a lack of staff, and soon a lack of guests to run after. Putting half of Edenwell to sleep was required to keep the place alive. But an investor was just around the corner, Chalice promised them with one of his ever-ready grins.

“These things take time. Here, you people do business like you’re dancing the two-step on a glacier.”

Oh, and when this investor got his act together… a new sun terrace, an expanded tennis court with a refreshment stand, and fine refurbished bedrooms with views of the landscaped gardens. Maybe even a proper Turkish sauna fit for a sultan, with great cascading monstera plants from the jungles of Panama. Chalice told Freddie stories of the big London hospitals, where canaries were bred in gleaming aviaries so every patient would have a singing companion for the duration of their stay.

“Would you like that, Freddie-fella? You have a way with the birds. How’d you fancy conjuring me up some canaries?”

Canaries needed sand and cuttlefish bones. The birds he was used to laughed at the idea of cages. But he could manage it, Freddie said solemnly. Yes, he most definitely wouldn’t let Doctor Chalice down.

When he told Fa, he received a fond slap. “You’re a canary,” Fa said. The idea was disappointingly never mentioned again, but Freddie took a scrap of butcher’s paper and made a drawing of a golden palace on a rolling dune of pristine sand.

Soon. The word on everyone’s lips.

Until then, it was Freddie’s job to interfere with the North Wing, and it disliked him accordingly. Each day, he unlocked the double doors and slipped through, turning the key behind him so no stray guests could follow him in error. Though the living portion of Edenwell could be trying, with the guests’ frank talk of bald pates and spreading waistlines, the North Wing’s emptiness rang loud with memories of those who came too late for the water’s magic. Women drawn and brittle, men shaking too hard to drink their soup. Freddie didn’t always notice guests as they arrived – in high season, Edenwell could expect up to twenty newcomers a day, sometimes together in a rowdy party – but when the most fragile visitors left, wheeled into private cars by manservants and white-capped nurses, Freddie often felt a nudge of personal failure.

There was a fat cobweb swinging in the draught caused by his entrance. Freddie swiped his broom at it, pretending it was a broadsword. The spiders loved the old Morton family crest, high up in the ceiling frieze. It had always frightened Freddie, that story. Given a few ales, Nick Scole was known to do a fearsome turn as the hermit Lord Morton, his brain softened by age and indolent living, swinging his hammer and turning every last coat of arms in the house to dust. Grief for his only son, killed by assailants unknown. The frieze in the North Wing was the only one to survive, being just out of Mad Morton’s marauding reach. Missus Hardy the cook said he pulled up the kitchen flagstones and dug his own grave there. But servants would say anything to break up the monotony of the day.

Freddie made his apologies to the spiders and hurried on.

The North Wing was laid out in an open ward style, offering cheap, comfortable beds in opposing rows for Edenwell’s cheaper, less comfortable guests. There were five fireplaces, spread down the centre of the long room to evenly heat the beds in the raw East Anglian winter. Freddie went to each one, knelt down, and felt about inside with the broom handle. It was his childish fear that one day he would dislodge a pair of human legs, but there were no limbs that morning, just clods of chimney dust and the odd twig from the nests perched high above. It was not unknown for a pair of fighting jackdaws to slide all the way down a chimney, bursting out into the room, furious but unharmed. Freddie kept an envelope of stale bread in his waistcoat for that eventuality. Better to coax them out than chase them. They remembered that sort of thing.

The beds remained, stripped and empty, with a locker and washbasin each. Freddie was always thankful they had pulled back the dividing curtains before closing the wing. It was easy to succumb to uneasy feelings in such a long, silent room, and each time a stray breeze caught a curtain Freddie found himself thinking of the hikey sprites who moved with the sound of rustling leaves and got you if you left a candle burning at bedtime. But there were worse things to stumble upon, he reminded himself. Like Nick Scole with a girl.

Freddie got down on his knees at the fifth and final hearth, jabbing his broom handle about in the dark. Something plopped between his knees, showering him in dust and soot. His breath stopped in his throat as he brushed aside the crumbling dirt. The delicate architecture of a spine.

Drummerboy had been gone a month.

Outside, the rooks cackled. A knave counts the days.

“Stop that,” he hissed.

Nothing but mouse parts: an owl pellet. Freddie swept it up. He heard the owl at night, screeching as he tried to sleep. Birds calling in the dark had always made him nervous. He supposed it was Fa’s fault. When Freddie was small, his father took a fledgling jackdaw from a nest and locked it in a cage hanging outside the cottage door. Jackdaws had always been friends of farmers and field-dwellers, he told Freddie. A tame one would loudly tell the master when a stranger approached. “A guard dog’ll be bribed,” Fa said, “but not one of these boys.” Birds saw things men did not.

Young Freddie saw the cage and felt an overwhelming glee at having this wild thing at his command. Fa didn’t want to give it a name – “You mustn’t grow fond” – so Freddie only called him Wellington in private. He fed Wellington bits of bacon fat and sang songs to him.

The grand old Duke of York

He had ten thousand men

He marched them up to the top of the hill

And he flew – exploded! – swept a black broom down the land andthen…then…

When Wellington died, Freddie wept. He cried so long, Fa went to Doctor Chalice for something to soothe him, but the doctor said he should be allowed to grieve. Fa gave Freddie some beer and disposed of the jackdaw in the hospital furnace. For weeks, Freddie dreamt of Wellington calling to him in the night, wanting more bacon, more songs. He took the empty cage down to Choke Wood and watched it sink in the old well.

He dusted up after the owl pellet and brushed off his trousers. Drummerboy would have said something if he was going for good. Freddie had been over his weather diaries with the utmost care. There was nothing – no sudden flare of rain or gales – to spook the bird. Nothing he could see suggested an omen. Drummerboy had simply gone.

That was the way of it now. Most of the orderlies were gone. Mister Daventry and Mister Rhodes went right at the start when it all felt like a big party. Doctor Chalice shook their hands and said he’d keep their white uniforms pressed and clean for their return. Clarence, the farrier’s boy, was an inch too short but they let him go anyway. Freddie could hardly remember John Pollard who used to deliver the coal. And what about Scole? Scole had come back. And look at Scole.

But those were people. And people didn’t work in the sensible circles animals did.

He set about checking the windows. It was mechanical up-down work that made stars glitter in his eyes, sweeping his hands over the outer sills searching for rotting patches, and when the last window was done, his heart was labouring as though he had never taken Doctor Chalice’s healing water at all.

He rested against the sill. Fa was down on the driveway with the Albion van, craning his neck, waiting for Freddie to notice him. He was waving his cap, and not cheerfully. In his other hand, something dead.

* * *

“Here he comes. That’s right, nice and leisurely.”

If the pines of Edenwell could up roots and walk, they would strongly resemble James Ferry. At sixty-six, he was an old father to such a young son, but he carried out his duties with a glum humour which endeared him to everyone at the Hydropathic, his home for nearly thirty-five solid, careful years. Freddie had inherited his Fa’s rather bashful, long-legged demeanour, but not much else. If any of the guests had seen the pair of them on the driveway that cold morning, they would have assumed this was a groundskeeper who would rather be alone, and an apprentice who felt similarly.

The squirrel dangled heavily in Fa’s grip.

“It needs burning. But for now, we need traps.”

Freddie tugged thoughtfully at his bottom lip. “I’ve never trapped a fox.”

“A fox takes his leavings. Besides, they kill with a bite. Look at this.” He pressed the limp animal into Freddie’s hands.

The squirrel had been all but crushed. A motorcar would have left a clear track across the body, but the unfortunate creature was crumpled like a bullet. Freddie’s sketching eye was drawn to the strange fall of light and shadow; a crater where the ribcage once swelled, broken angles interrupting soft fur. It was spongey to the touch, a cold bag of skin, and Freddie gave it back.

“I’ll set a snare,” he said.

“Snare won’t do it. We need an ironmonger.”

The weight of the metal settled into Freddie’s core. He stole a look at the van.

“You has to learn,” said Fa.

The Albion van was already loaded with shears and lawnmower blades for the knife sharpener. In Freddie’s opinion, he had done enough learning. Learn to clean your boots of an evening, said Fa, learn to focus on the task at hand, learn to say good morning. And he had, but only when Fa was there to hear it, and sometimes in the afternoon.

Fa opened the driver’s door. “Three or four traps, I reckon.”

Freddie put his hands in his pockets. There were pencil stubs to fiddle with. “There’s litter on the bowling green. While you’re off, I can clear it.”

“Can’t lug four traps alone.” Fa looked him over, and when the annoyance in his face passed, Freddie noted the drop of concern underneath. “You sickening for summat?”

He could say his heart was off. It had been hard to sleep lately with it thudding away like a drunken dancer. But he didn’t want to worry Fa.

“Just hungry.”

“We’s all hungry,” Fa grumbled, and gave him a gentle shove towards the van.

Freddie scrunched his long body into the passenger seat. With the window down he could hear the rooks calling. He looked to the trees. In town, there would be motorcars and horns and the clatter of horses and the squabbling of trade, all simmering around him until his head was boiling. He had tried to articulate the sensation to Fa, but the answer was always the same: he had to learn.

The van spluttered into life. When Doctor Chalice purchased the property, long before Freddie was born, he was struck, he said, by the aloof beauty of the breckland, with its mounds of bristling heather and spires of blue viper’s bugloss. He put that in the brochure, a romantic quotation beside his serene portrait. A guest could take to the tennis courts and see almost all the way to Thetford, or walk through Choke Wood and emerge into the brecks where Freddie spent his boyhood searching for dinosaur bones in the sandy furrows. Guests came from smoky cities which teemed with motorcars; some had never encountered such peace. Freddie always wondered, why would anyone make the mistake of leaving?

When they came to the gates, Fa clambered out to open the latch, shooing away a pair of perching rooks. The gates of Edenwell were another of Chalice’s flourishes, a boundless ocean of winding iron. Freddie was too young to have ever seen the old gates before the rusted remnants were tossed away in Choke Wood, down in the well that swallowed everything offered to it with black indifference. The original gatehouse was long gone, but if Freddie were to believe the more ancient guests, it was a grim ecclesiastical thing, a relic of Edenwell’s days as a site of pilgrimage. Better off demolished. “Monks are mawkish,” Chalice said. “They had to go.” Nowadays, instead of holy grace, a drink from the Edenwell springs brought clearer skin, stronger lungs and renewed husbandly potency. Respectable science, recommended by Good Housekeeping.

Freddie was jolted out of his reverie by Fa opening the passenger door. He nodded at the driver’s seat. “Off you go, then.”

Freddie’s stomach rolled. “We could’ve had a horse.”

“Who’d feed the horse?”

“You feed this.”

Besides, you couldn’t talk to a van the way you could to a horse. Couldn’t get to know each other. Freddie wanted a giant plodding shire horse with feathered feet, but Doctor Chalice gave them a gleaming 1914 Albion van with the hotel’s name emblazoned on the side, and Fa expected him to drive the thing.

Fa’s grim old face was so hopeful, Freddie couldn’t bring himself to refuse. He climbed over the gearstick and settled into the driver’s seat, feeling the shape of his father’s bony backside under him, stamped into the leather.

“There’s a lad. Foot on the accelerator, gentle as a lamb. Ease up the clutch.”

The van stalled immediately. Fa waited for him to try again. Key, clutch, gear, pedal, gentle as a lamb, KRUMPH. Freddie could feel his face turn red. On the third try, the van heard his prayers and sailed down the driveway. Automobile accidents were the worst, he reminded himself, second only to steam engines. When a train’s boiler blew up in Cardiff, bodies were found strewn five hundred yards away. He traced the picture from the newspaper at the time, a spray of monstrous metal ribbons. The wrecked locomotive resembled the twisted winter hazels down in the woods.

In the rear mirror, he saw Fa watching him.

“Are you reet?” Fa said.

“You angry with me?”

“You’re doing well. We’ll park her up behind the munitions factory. When we’ve bought the traps, what say we have a pie from Henby’s while we’re waiting for the knife boy?”

There were no pies to be had, Missus Hardy said so. No pies anywhere. Still, eating together, even sharing an apple, sealed up inside the car down a quiet street… If Freddie could focus on that, he might ignore the spindles of electricity turning at the base of his spine. It might almost be possible to touch the other side, the creaky haven of his bed and books and pencils.

He was almost feeling better when a bird rocketed across their path. Freddie hit the brake so hard he and Fa were slammed back into their seats.

“Heart alive!” Fa cried. “What’s the matter with you?”

Freddie swung out of the door, leaving Fa to pull up the handbrake. He looked up, spinning on his heel. A jackdaw, small for his age and uniquely half white, clattering joyfully across the sky and back towards the Hydropathic.

Freddie put his fingers to his lips and whistled.

“Drummerboy!”

White feathers sharp as lightning. His heart kicked against his ribs.

“Oi,” said Fa. “Where you going?”

“He’s back,” Freddie cried. “It was him.”

He heard Fa shout as he raced back towards Edenwell. “You see to them leaves in the fountain. Don’t doss about.” Then an afterthought, ringing out across the lawn: “I am not best pleased.”

* * *

There was a chunk of potato peel bread in the larder, half of which was his by right. Who knew how Drummerboy had changed this past month? Perhaps he’d lost his taste for potato bread, found someone offering something finer. As a rumpled chick, Drummerboy had yelled for food. Freddie would smear fish paste on his finger and allow him to clamp down, squackering with happiness. Freddie wished he had a tin of the cream crackers the little jackdaw couldn’t resist. He’d borrow the best hospital china to serve them on if it would tempt him home. And a napkin.

Freddie rushed to his room and threw open the window. All five of his hanging thermometers clattered like icicles against the casement. He hadn’t seen the floor in years, cushioned by a layer of books and newspapers, and the pictures pasted to the walls shivered in the breeze. The ceiling was dark with silhouettes of rooks and crows, copied from life. Fa disapproved. A gypsy once told him if you looked up and saw through a hole in a passing bird’s wing, you were born to hang.

Freddie sprinkled crumbs on the windowsill, trying not to dwell on the sad sight of Drummerboy’s empty bed, an upturned cap trimmed with twigs of the bird’s own choosing and a few fallen feathers. His food bowl was an ashtray purloined from somewhere – Freddie forgot. He snatched up Drummerboy’s favourite toys from the floor and arranged them by the window to tempt him in. A spool of thread, good for rolling. A disc of mirrored glass for inspecting his handsome face.

It was a funny way for a young man to carry on, Fa always said. Before the war, when he and Fa still went to Saint Peter’s church out in Thetford, Freddie listened with dread as the vicar spoke of casting off childish things. If Freddie were to cast off everything people wanted him to, there would be nothing left but bones. No Drummerboy, no paintboxes, no Martha Talbot picture books. Freddie knew every dog-eared page by heart. The Heroics of Harold Hedgehog. Moon Over Toadstool Hill. Those little books taught him to read and taught him to draw. Give a bird a crust, said Miss Talbot, and he’ll fill your dreary life with magic. Why cast that away?

Come back, he willed the empty sky. Since Drummerboy disappeared, Freddie dreamt that he himself had died, his spirit hanging over the hospital. Whirling below him, the rooks and the crows left offerings to tempt their lost human back to the brecks. A bar of Fry’s chocolate. Charcoals. Laundered socks.

But Drummerboy was not dead.

He went outside, watching the sky through his visible breath. He clicked his tongue, tossed chunks of bread, called the bird’s name. But the thin clouds were the only things watching over him. Drummerboy, if it had been him, was nowhere to be seen.

Freddie took the last handful of potato bread and headed for the trees. The guests were still breakfasting, emptied out by the previous day’s purging and massaging. No one would see him.

Freddie was privy to things not mentioned in the Edenwell brochure. Chiefly, he knew the four-tiered fountain on the front lawn was not the original holy well, as much as Chalice was happy to allow guests to believe it. The fountain, like the Gothic bandstand and the stone folly on the lawn, was a flourish of the Morton family’s wealth. The true well did exist, but down an uneasy path, an incline of pines where no guest in their slippers would think of venturing. As a boy, Freddie had been free to play in the gullies of Choke Wood, spoiling his trousers in the loamy dirt. Lead soldiers, a stick for a hobby horse and a bulrush for a lance. A boy didn’t need companions when he had such toys. Some of those soldiers were probably still waiting for him down there, reaching out from the bracken for their lost commander. But the well lay beyond, in the centre of things. It was never a place for playing.

He headed down through the frost-tipped bracken. Freddie always marvelled at how his cottage vanished when he stepped into the wood. Edenwell loomed – it could do nothing but loom – but his own little home could wink out of existence as quick as a sneeze. It was oddly comforting.

A few rooks clustered in the canopy, their bristly faces turned to Freddie as if he had intruded on a private conversation. As Freddie edged carefully down a rain channel, he spied one cracking a snail on a fallen log. A short black beak and strong talons made easy work of the shell. Somewhere, a pheasant shrieked for a mate.

The fountain on the lawn was a blousy affair of whorls and trimmings, but the real holy well was far more beautiful to Freddie. The first one saw of it was a mossy stone easily mistaken for an oak split by a gale. It had once been a column, one of four, framing the circular pool. Freddie fancied there had originally been a golden cloth draped over the water, turning each ripple into a display of molten metal. Now leaves and algae made soup of the water, and the steps pilgrims had trodden for centuries were reduced to a shapeless slope of flint and mortar.

At the back of the well was an altar of sorts with an alcove where Fa said a Popish statue had once presided over the water. The nuggets of pork rind Freddie had laid out inside the alcove a week ago were gone, as he expected. The rooks knew what it meant to find Freddie down here, and they gathered above him, greeting and jeering.

“Have any of you seen Drummerboy?” he called out.

What’s it worth to a knave?

“Traps are coming. But not for you.” With chalk from his pocket, he sketched a jackdaw’s stubby head on the altar. “My friend. If you see him—”

His audience snickered. A crack of twigs at the top of the gulley. Freddie stiffened, but it was nothing more than a hefty partridge grubbing about. He thought about the pork rind, how hungry he was. He should have brought his rifle.

“We’re finding dead pigeons every day now,” he said. “And hedgehogs, and squirrels. It’s not eating them. And it’s very nice for you, because it’s easy meat, but it could be a wild cat, and they in’t fussy.”

The rooks laughed, and he reluctantly joined in. Nothing worried them. What was their trick?

He tore the bread into pieces and laid it out in a ring around the drawing of Drummerboy. As he withdrew to the edge of the well, the rooks swept down to claim the scraps. Feathers flashed blue in the morning light.

Watching them feast, Freddie dreamt of omelettes swimming in butter. Of plates of ham and cheese. He could open his ledgers at any page and see dashed-off drawings of pre-war teas with Fa, of toffees sucked in the street, Christmas dances at the Hydropathic with plates of sugared almonds. There was nothing in the shops these days, just women talking, women working, women where men once were. The town crier was a girl now, and Freddie had listened out for her shrill ‘Oh yea!’ with uneasy fascination. Sixteen-year-old Florrie Clark with her long hair in ribbons, pasting up recruitment posters. Men of Thetford, you are urgently wanted.

His hands were covered in black potato rind and chalk, and he squatted by the water. He dipped his hands in up to the wrists, as pilgrims had for hundreds of years. The cold tremored in his pulse, clearing his mind of everything but how lonely he would be without the little jackdaw to come home to.

What more could he give?

* * *

The boyish figure of Lottie Mulgrave pushed through the dining room doors and out onto the veranda. She was rounding up the second chorus of ‘A Little of What You Fancy Does You Good’, her breath a white plume to match her Turkish cigarette. Lottie was Edenwell’s resident celebrity, known better as Colonel Crumb of the vaudeville circuit. The laughing Irishwoman’s morning performances had come to be part of the Edenwell experience. At the fountain, scooping leaves, Freddie could hear the late breakfasters call for the Colonel’s more ribald numbers. Lottie, her yellow braids bright against her paisley dressing gown, hailed Freddie with a salute of her fag.

“Morning! He’yer fa’got a dickey, bor? Come now, you know how it goes: ‘Yis, an’ he’ll want a fool ter ride ‘im, yew comin’?’ We must work on your repartee, kid.”

Lottie tipped her head, hearing something above. A second-floor window was thrown up, revealing half of Doctor Chalice, clapping with his usual happy sincerity.

“You’re in fine voice, Miss Mulgrave,” he called down. “I trust that’s Edenwell water in that tumbler you have there?”

“Frightfully soothing, thank you, Doctor. Though one has to temper the taste with a little something stronger, I find.”

“And you, Freddie-Fella. Caught any carp?”

Freddie shrank in the light of attention, but managed a grin. The skin of ice clinging to the fountain’s rim took several hard thwacks to break.

“Come up here a minute,” Chalice said.

Freddie held the net aloft. Busy.

“That’s a shame. There’s a small stipend in it for you.”

Freddie didn’t know what a stipend of any size was, but when Chalice mimed the opening of a book and the flourish of a pencil, he put down the net.

Matthew Chalice was handsome in the way any sixty-something man could be, given a sensitive barber. But his smile transformed him. One quirk of his sandy eyebrows made everyone he met feel included in an exclusive, clever joke. His accent had mellowed in the years spent in Norfolk, but there was still a trace of the Midwest in it, enough to make even the sternest spinster turn buttery as she signed her name in the guest book.

Freddie enjoyed any moment spent in Doctor Chalice’s company, but to be invited inside his princely den was a special treat. He could sketch it all from memory; the model cars, the crystal bowl of carnival-coloured candy shining on the wide, dark desk. Along the mantelpiece, a row of beer bottles paid homage to the Chalice family brewing empire, the fountain of his wealth. But it was the pictures Freddie liked, modern American cities with buildings so tall they could scratch the clouds and leave a scar. Framed photographs of film actresses, reed-waisted and dreamy. Freddie had never seen a film. When Freddie was small, Chalice permitted him to copy the pictures sometimes, crunching butterscotch while Chalice caught up on paperwork by the fire. Freddie was a man now, but that juvenile wonder came roaring back the moment his eyes fell upon on the gleaming telescope.

“My latest acquisition.” Chalice grinned, patting the tripod.

All that glossy bronze. Freddie saw his face in it, the longing shape of his mouth.

“Want to see something remarkable?” Chalice coaxed him to the eyepiece and showed him where to point it.

At first all he saw was sky, the same empty space he’d watched for hours saying prayers for Drummerboy. Then, dancing on the horizon like a kite: an aeroplane. Forest green, with a red tail and target circles on the wing. It seemed to be flying for the joy of it, turning like a swallow.

Then he saw the guns.

“It’s got teeth.”

“Big ones. Lewis gun. You’d know about it if she bit you.”

“What’s it doing here?”

“There’s an aerodrome out in Snarehill now, and Lakenheath. And what about you? Where’s father Ferry this morning?”

“Town.”

“Couldn’t convince you to accompany him, I take it?”

Freddie said nothing. The aeroplane turned a slow arc as Chalice gently took Freddie’s wrist, watching the clock over the fireplace.

Freddie took the focus off the aeroplane to scan the woods for Drummerboy. Beyond his cottage, Choke Wood was almost naked after the worst of winter, blotched with nests. In the tallest trees, the rooks gathered. A ripple went through the mass of black; they knew he was watching them. They no doubt wished they had a telescope of their own. Think of what a rook could do if he could see into every guest bedroom, spy every indiscretion and petty human embarrassment.

“You’re not feeding them, I hope.” Chalice released his wrist, satisfied with whatever data he had gathered. “Defence of the Realm Act, fella. You could be prosecuted.”

“Why did you need to see me, sir?”

“I have business in Thetford. I need to pay an old colleague a visit, but then, more pleasingly, I have an order to pick up from the stationers. I could use the help. Paper is heavy. Of course, you wouldn’t go home empty-handed, if you’d oblige me.”

It was the one carrot guaranteed to tempt him. Freddie had only the most basic of schooling, so Chalice had taken his education into his own hands, providing composition books, pencils and instructional works of literature for Freddie to take to his little room in the groundskeeper’s cottage and absorb. Freddie imagined it gave Chalice a pleasant, charitable feeling to think of him hunched by a candle long after bedtime, attempting sums and letters with the materials he provided. Chalice might be less pleased to learn how Freddie filled those ledgers, or what happened to the books with pictures in them. He could feel the doctor’s inquisitive gaze sometimes, cast down from his office where he sat up in the evenings, nursing a brandy while Freddie scribbled and daubed.

“Finished it,” Freddie would say, a touch awkwardly, each time he visited Chalice to ask for a fresh ledger. Then, one day, sudden and unbidden as most of Freddie’s communications were: “Colours. Are colours summat you can buy?”

Chalice was pleased to oblige. But what were Freddie’s plans? Botanical sketches, perhaps? A budding naturalist? Colours? Certainly! All the colours of the imagination. But could Chalice see inside that ledger he was clutching? Could he take a peek? Freddie spooked easily. The thought of showing his drawings to anyone besides Drummerboy made his guts clench. Chalice didn’t push the matter. That Christmas, a box of watercolours from Walker’s Stationers, nicely wrapped. Nothing so extravagant as to embarrass the senior Mister Ferry, of course. He was perfectly content with a bottle of brown ale.

“Fa couldn’t spare me, sir. He’ll want help with the traps. He thinks it could be a wild cat.” Freddie tugged on his lip, thinking about it. “Maybe a distempered dog.”

“Fella…” Chalice gently took the telescope and replaced the lens cap. “If you don’t get over it now, you never will.”

WHO made these little islands the centre of the greatest and most powerful empire the world has ever seen? Our forefathers.

WHO ruled this Empire with such wisdom and sympathy that every part of it – of whatever race and origin – has rallied to it in our hour of need? Our forefathers.

WHO will stand up to preserve this great and glorious heritage? We will. ENLIST TODAY.

Fa liked the poster outside the Tribunal, Freddie recalled. No pictures, no silliness. Plain talking.

When Freddie emerged from the Guildhall with a piece of paper in both hands, he watched as the lines of tension on Fa’s face melted away. His father made a show of studying the poster, but Freddie had his exemption. It was safe to like things again.

“They measured me. Listened to my chest.” Murmur, they called it. As if his heart were a dull child who needed to speak up. “Category E. Grade 4. One of them said maybe send me off as a cook. But the others were adamant.”

They didn’t embrace.

“Well, they know best,” Fa said. “I reckon we can stretch to a quick half in the Red Lion before heading home.”

Freddie didn’t recognise the old woman watching them. She had stopped by the steps to open her umbrella, but he could feel her picking apart their conversation. He touched Fa’s arm, silently agreed to a drink so that they could walk away from the crowded marketplace, but the woman took her opportunity.

“All smiles, are we?”

Fa pivoted. “Beg pardon?”

“Ought to be ashamed, parading about like that. A big lad like him. Shirker.”

They could have walked away. Turning it over in his mind a thousand times since, Freddie could list as many methods of leading his father away. But her words lit a taper Freddie hadn’t seen before or since.

“Shirker?”

“Fa—”

“Don’t you turn away from me. Shirker? His mother died before his eyes were open. He nearly went with her, his heart was so weak, so keep your opinions to yourself, if you don’t mind, madam. You join up if you’re so keen.”

He was shouting by the end. How people stared. Market grocers, bicycle repairmen, housekeepers with baskets on their arms. People who knew them. And it didn’t take a tribunal panel to understand the looks on their faces, and where their sympathy lay when the woman stepped back, her lip flapping in distress. Freddie wanted to turn heel back to the Guildhall and beg them to give him any old uniform, any old post.

“Bitch.”

It was the first and last time he heard such language from Fa. But it was that other word, spat out like gristle, that ran through Freddie’s head at night and made his forehead prickle. He couldn’t look into his shaving mirror. In his own eyes he saw those of the old woman, narrowed, disgusted; the eyes of the friends she surely told; the eyes of everyone who heard the tale, feeding it and breeding it until everyone in Norfolk knew there was a shirker in their midst.

Habit turned him to the comforting books of his boyhood, but even Martha Talbot had turned against him.

A coward isn’t always plain to see. Like a chameleon, he changes his colours on a whim. Like a fox, he goes to ground. Like a cheetah, hewill dash away in the blink of an eye. But unlike all these animals – all God’s dazzling furred and feathered creations – a coward comes in but one form, and that is Man.

Freddie tore out the page and with a pencil committed his own form to it: a dishevelled dawdler, all legs and elbows, frowning in ill-fitting clothes. He took it down to Choke Wood and drowned it in the well.

Doctor Chalice brought him round with a pat on the back. “Give me a couple of hours to prepare my things. I’ll drive. Now go and scoop those leaves. It’s a good day, fella. We’re taking off.”

* * *

He scooped the leaves. He fed the chickens. He pulled the milk thistles from the parsnip patch where Mister Tungate’s gardening hat hung mouldering on the hook. The gardener left it there two full years ago, and now it had cultivated flora of its own. Freddie stretched, looked back at the strip of sky over the Hydropathic. Empty. He’d tossed his breakfast to the birds, and now he was empty too.

With the guests’ morning victuals over and the luncheon broth simmering, Freddie could try his luck for leftovers down in the kitchens. When he reached the bottom of the twisting stone stairs, Missus Hardy was rolling out pastry perilously close to Nick Scole’s wooden leg, shiny and strangely massive on the table. It made Freddie queasy that it wore a real shoe. Scole had his trouser leg rolled up and was rubbing ointment into his stump, and when Freddie noticed an unfamiliar girl skulking by the pantry door he knew why. Squat little bruiser, with a long-skirted Edenwell uniform and a mouth like a scar. She watched the orderly, arms folded, as if to say he couldn’t scare her.

“A lot of the lads likened it to Hell, but I’ve never seen Hell and I’m not one to draw false comparisons.” Scole took a gobbet of ointment and warmed it in his palms. Freddie could see the pink tideline where a flap of skin had been folded over under the knee, packaging it up like a jam roly poly. “Still. I have seen France. And I’d forgive any fellow unable to tell it apart from the Book of Revelation.”

Missus Hardy shielded her flour from Scole’s bristled thigh. “Do you mind?”

The new girl spoke up. “I spent eleven months filling shells.”

Scole didn’t look at her. “I ’spect you stopped once your pretty hair started coming out, didn’t you?”

The girl’s cheeks coloured, and not charmingly. “My mum made me give it up.” She rolled up her sleeve. Freddie was surprised to see a cross on her burly forearm, mortuary black, with a name underneath. Thomas.

Nick Scole saw. His face was unreadable, but he made an approving noise. So long, Thomas.

Missus Hardy paused rolling pastry to wipe her brow on her sleeve. “You sneaked in, Freddie. This is Tabitha Clarke. She’ll be taking some of the strain for Annie and Maud in the guests’ rooms and helping me down here from time to time.”

Scole screwed the lid back on the grease and began the laborious task of reattaching his leg. Leather and laces and creaking callipers. It reminded Freddie of a suit of armour, only there was no flesh for it to cover and protect.

Will a knave ask where he left it? We are peckish boys and girls.

Scole’s hands were too greasy to tighten his straps. “Freddie never served, Miss Clarke. The Home Office wouldn’t let him go – thought they’d give the Boche a sporting chance.”

“Lay off, Nick,” Missus Hardy said. “There’s a bun there for you, Freddie, you can share it with your father. I’m making stock from the ham, so keep your mitts off.”

Freddie tugged at his lip and mumbled his thanks. Tabitha stared.

“How’d y’do?” she said tonelessly.

Good morning. That’s what Fa would want him to say. The bun wouldn’t quite fit into his pocket. “Don’t go into the woods.”

Nick Scole barked with surprise. “You what?”

“We’re laying traps,” he blurted. Everyone’s eyes were on him. His face started to burn, so he focused on the bone bucket on the floor, a heap of used-up whiteish rock. “We think it’s a dog. It could be foaming at the mouth and you shouldn’t go wandering.”

Missus Hardy was less inclined to amusement. She beat the flour from her hands. “Well, that’s a fine welcome for Tabitha, isn’t it?”

The new girl glanced at Scole, who was snickering still. Her hard mouth twisted, but then she was looking past them all, up at the window close to the ceiling where a dainty hand tapped on the panes.

Tabitha drew back in disbelief. A little princess in a blue gown bent down and waved.

Scole saw it. “Bugger off!” he yelled. He went to get up, forgetting his leg, and irritably hurried to reattach it. “You been feeding him again, Missus Hardy?”

The princess drew back, the tiny hand frozen mid-wave. Her sweet porcelain face was replaced by a flappy-soled boot, then a bent knee, followed by a dusky beard pressed to the window. Wearing a look of bovine confusion, the weathered complexion couldn’t be more different to the sweet marionette’s. Poor old Mister Jenks, a creature of such grime and grit Freddie could have believed he had been born straight out of the earth if it weren’t for his pristine puppets. People said he made them with his own crooked hands.

Scole bellowed up at the window. “I know you can hear me, you old goat. Clear off! I’ll ’ave you.”

“He only wants a cup of tea,” said Missus Hardy.

“You bring him in here, we’ll all be itching. You can make me a cup of tea, if you’re desperate for something to do.”

Tabitha was trying to get a better look at the princess. “Who is that?”

“The real reason you shouldn’t go into the woods,” said Scole.

It was as good a moment to flee as any. Freddie ignored their laughter as he slipped up the stairs.

* * *

When the war began, men queued to volunteer. They queued to have their measurements taken. They queued for khaki tunics.

If they were lucky lieutenants, their mothers went to department stores and bought them brown belts and swagger sticks. They had their pictures taken for the parlour wall. Freddie was not a lieutenant, nor a ten-a-penny Tommy Atkins, and he had no mother to frame his picture, so before the awful day of the tribunal he made do by standing in front of the mirror, posing with his chest puffed out and Drummerboy on his shoulder. Captain Ferry, Bane of The Kaiser.

But the Kaiser didn’t hold his attention for long. As the months went by, Freddie was half convinced France was a place they’d concocted to hide where all the men were really going. Letters came, but they weren’t written by anyone Freddie recognised. Postcards with pre-prepared statements, scribbled over in pencil where applicable. I am well andhappy […] andam going onwell […] Ihave received yourpackage […] signatureonly on this line.

Now he and Doctor Chalice drove past Dales, the butchers. Poultry hung in the window, three birds where twenty once dangled temptingly. Harold, the butcher’s apprentice, was keen to go. People supposed he was, anyway, but Freddie thought his face said one thing and his mouth another. Harold and his nimble fingers joined the Navy. What went on at sea, Freddie didn’t know, but he and everyone else prayed for Harold at midday chimes. Freddie could hardly recall the shape of Harold’s face, let alone the boundaries of the ocean. Perhaps they were down a great black hole somewhere, a slave encampment, building pyramids all day. Freddie drew pyramids sometimes, great tricky tombs for him to hide in, his body safe beneath the deep cool stone.

He’d tried to draw Harold as he remembered him, doling out chops at the counter. A year later and he needed the paper, so now the butcher’s boy dawdled alongside Saint George piercing the dragon, a page boy proffering a plate of serpent’s meat.

Freddie remembered Thetford on market day as practically shoulder-to-shoulder – horrid thought – but Doctor Chalice had conjured up a fine rain to stop people milling about. Chalked outside Mitchell’s Grocers: SOLD OUT BUTTER. All Freddie could think of then was buttered toast, buttered muffins, butter melting in his mouth like sunshine.

Chalice smoked as he drove, drumming a tune on the wheel. As they passed the meadows where the abbey ruins stood tall, he sighed with pleasure.

“I will never become accustomed to that sight. Living alongside the Middle Ages. When I come here, I feel like a noble knight.”

A knight and his squire, riding out. Yes, Freddie liked that. Knights never ran out of butter.

“Doctor Ridley’s office is near Burrell’s factory,” Chalice said. “I need to pay him a visit.”

“Is the new girl from Burrell’s?”

“You met Miss Clarke? Yes, a munitionette. Why? You like her?” Chalice made a naughty face.

“She made… bombs?”

“Big poisonous things, spoiled her skin. She was like a canary when I found her.”

Chalice slowed, allowing a pair of women to trot across the road. Their skirts dark with rain.

“Do you remember what you said a few Christmases ago, about breeding birds for the guests?” Freddie ventured. “I was thinking, the old folly. We can sort out the draughts and make it nice. When we open up the North Wing again, we can bring in some pairs of canaries, and I can keep them happy.”

“I suppose that leaves Ferry Senior to deal with the wild cats, doesn’t it?”

Freddie stole a glance at Chalice, feeling he ought to elaborate, prove he wasn’t making frivolous demands. “One of the lady guests said she wanted something to dote on. The lady with the stammer, you remember. I think it could have helped her, to have a friend.”

Chalice looked ahead, a small smile on his handsome face. He breathed a long stream of smoke until Freddie couldn’t see the American’s eyes. “It’ll all be different soon.”

“Soon?”

“I believe it.”

As the town swelled around them, the streets narrowing, Freddie could feel his heart protesting. “I’d like to look in Walker’s.”

“On a fine day like this? Only if you promise to take this and spend it on something frivolous.”

Chalice tossed him a coin and dropped him off at the shop to save him getting wet. There was a new sandwich board outside the door:

The boys are doing splendidly in Egypt, Mesopotamia, France. Another Bahamas contingent will be sailing soon. Roll up, men! Make it the best. GOD SAVE THE KING!

Pyramids, Freddie quietened himself. Deep in a black safe tomb.

Much like a pyramid, Walker’s was a gloomy cavern, one of the primary reasons Freddie liked the place. The windows were stuffed with prints and books, washed out by years of lacklustre Norfolk sunlight. There were two customers already inside: a woman buying baccy and a small boy waiting for an opportunity to pocket a bar of Fry’s from the display on the counter. Pillowy Missus Walker was in charge these days. She had a bad hip, and it was an agony watching her laboriously fetch things for the more impatient customers, but Freddie felt comfortable around her. Mainly because she couldn’t appear suddenly by his side, asking if he needed assistance. In addition to shelves of papers and sweets, her absent husband had amassed a wonderful collection of oddments. Freddie could happily root through the shelves and boxes for hours and never run out of artefacts to unearth. Postcards and watercolour tins and fat sticks of chalk. Penny mysteries and second-hand toys. Not everything good had passed away.

Towards the back of the shop, behind a stack of shelves, was a travellers’ chest of disintegrated books. He spotted Martha Talbot and her forest creatures straight away, like old friends. The works of Dickens and Stevenson muddled alongside Moon Over Toadstool Hill and elephantine Bibles. He was drawn to a bundle of precious colour illustrations, loose pages of turtles and bobcats and fabulous birds. A vivid macaw caught his eye, flamboyant and grinning. Take a rook and wash him in a jungle waterfall and the dye of his feathers will wash away like so much soot, he thought. How to put that on paper? Indian ink? A few drops of water? And underneath, the fabulous macaw, laughing at his own magic.

The bell above the door tinkled. A woman and a man entered the shop. They were arguing in a friendly manner – chaffy talk, Fa would say resentfully. Young townies who wanted everyone to hear how clever they were. The woman wished Missus Walker a good morning, laughter in her voice.

“If only someone had told you to bring a scarf,” she remarked to her companion. “If only someone – say myself – had informed you it’s February.”

“Look, I’m so used to filtering all the useless information you come out with…”

Behind the stacks, Freddie listened. The woman was young and petite, with a birdy jauntiness to her voice, but he couldn’t fix the man. Mostly, he wanted to know if they were coming his way so he could pay for his macaw and go. Peeping out, Freddie could see the woman’s red pigtails and a little of the man’s back as they lingered around the newspaper racks. He was much taller than his companion, made more so by a long overcoat, but the lanky, insouciant way he moved told Freddie he was a lad of his own age or thereabouts. That was an unusual sight. A soldier on leave, perhaps, or a useless person like himself. Nothing appeared to be wrong with him, apart from refusing to take off his hat. Freddie watched the stranger’s narrow back as he paid a ha’penny for the Daily Mirror.

“Lieutenant-Colonel Broadstair,” the young man read aloud as the woman chose from a stack of postcards. “Yorkshire Light Infantry, brother of the Mayor of Sheffield, was killed in action last week at… I can’t pronounce it. Malines?”

The woman dubiously compared two postcards of Marie Lloyd and her

toothsome smile. “Malines like marine, not malign.”

“Turned out to be pretty malign for him.”

“Would Mother like a local interest postcard, do you think, or something flowery?”

“There’s an excellent picture of him. The Lieutenant-Colonel. Will you look?”

“We didn’t know him.”

“Look. I think he looks very fine.”

“Jodhpurs make men look silly.”

“Heaven forbid a man looks silly as he’s slain by the Hun.”

“Eustace.”

Behind the counter, Missus Walker busied herself with a duster. Her husband was with the Royal Artillery and the words were hurtful. The boy – Eustace – ruffled the paper, turning to a depiction of a U-boat gliding like a shark underneath a supply ship. A black nest of hair peeked out from his cap. Freddie could still only see a slice of his profile through the shelves. He