9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

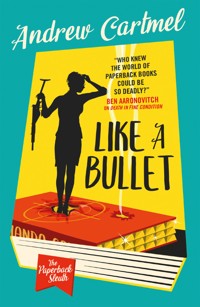

Launching a new series, a cast of lovable rogues face fiendish puzzles and murderous villains in this love letter to Agatha Christie murder mysteries and classic whodunnits. Introducing a new series from the creator of the beloved, bestselling Vinyl Detective novels. Cordelia knows books. An addict-turned-dealer of classic paperbacks, when she's not spending her days combing the charity shops and jumble sales of suburban London for valuable collector's items, she's pining for the woman of her dreams and nimbly avoiding her landlord's demands for rent. The most elusive prize of all, her white whale, has surfaced — a set of magnificent, vintage Sleuth Hound crime novels. Gorgeous, and as rare as they come. Just one problem. They're not for sale. Still, that won't stop a resourceful woman like Cordelia… One burglary later, the books are hers. Unfortunately, the man she's just robbed turns out be one of London's most dangerous gangsters, and now he's on her trail and out for blood. Cordelia's best laid plans to pay the rent and woo the object of her affections start to fall apart, and she realises she may have placed herself in the crosshairs of a villain torn straight from the pages of her treasured novels.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue: A Perfectly Nice Girl

1: Forgery

2: Book Hunting Terms

3: Sainted Not Stained

4: A Crate of Crime

5: Guilty

6: Weed

7: The Photo

8: Green Butter

9: Self Care

10: Break-In

11: Jackpot

12: Curry and Loot

13: Bath Night

14: Paperback Sleuth

15: Book Fair

16: Blue Note Paper

17: A Commission

18: The Paperback Sleuth’s First Stakeout

19: Benched

20: Double-Decker Karma

21: Allotment

22: Exonerated

23: Coffee At Sadie’s

24: Burning Oil and Detonation

25: Exorcism

26: Countermeasures

27: Timber

28: Edwin

29: Cath Kidston

30: Al Fresco

31: The Eyes of St Drogo

32: Amber

33: The Devil’s Liquorice

Acknowledgements

About the Author

“An intriguing mystery with an amoral protagonist. Who knew the world of paperback books could be so deadly?” Ben Aaronovitch

“Andrew Cartmel introduces a new kind of heroine, entirely immoral, somewhat venal and slightly foxed.” David Quantick, Emmy award-winning producer of VEEP

PRAISE FOR THE VINYL DETECTIVE

“A surprising, refreshing story… this novel is a winner… the series will be a hit.” New York Journal of Books

“A quirky mystery of violent death and rare records.” The Sunday Times

“One of the most innovative concepts in crime fiction for many years. Once you are hooked into the world of the Vinyl Detective it is very difficult to leave.” Nev Fountain

“This tale of crime, cats and rock & roll unfolds with an authentic sense of the music scene then and now – and a mystery that will keep you guessing.” Stephen Gallagher

“Crime fiction as it should be, played loud through a valve amp and Quad speakers. Witty, charming and filled with exciting solos. Quite simply: groovy.” Guy Adams, critically acclaimed author of The Clown Service

“This charming mystery feels as companionable as a leisurely afternoon trawling the vintage shops with a good friend.” Kirkus Reviews (Starred review)

“Marvelously inventive and endlessly fascinating.” Publishers Weekly

Also by Andrew Cartmel and available from Titan Books

THE VINYL DETECTIVE

Written in Dead Wax

The Run-Out Groove

Victory Disc

Flip Back

Low Action

Attack and Decay

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Paperback Sleuth: Death in Fine Condition

Print edition ISBN: 9781789098945

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098952

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: June 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organisations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Andrew Cartmel 2023

Andrew Cartmel asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Ann Karas

“We now anticipated a catastrophe,and we were not disappointed.”

—Edgar Allan Poe, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym

PROLOGUE: A PERFECTLY NICE GIRL

He was dead all right.

The man was lying on the floor in front of Cordelia. She stared down at him as the wind screamed through the broken window in the storm-wracked night outside.

He was dead, beyond question.

He was dead and Cordelia was glad he was dead.

Also lying on the floor, some distance from the man, a reassuring distance although Cordelia supposed it didn’t really matter anymore, since he was now dead, was the gun with which the man had so recently been trying to kill her.

Cordelia was breathing hard in a ragged rhythm and, hardly surprisingly, her eyes stung with tears. What perhaps was surprising was the reason she was crying.

It was the unfairness.

The sheer unfairness of it.

Cordelia was a perfectly nice girl—she really didn’t think that it was being immodest or overstating the case to say this. She was a perfectly nice girl and it was entirely unfair that she should have ended up in a situation such as this.

It was like something out of the crime stories of James M. Cain, she reflected as she stood there listening to the wind screaming in the night and looking at the dead man lying at her feet and trying hard not to think about where she was, what had just happened, and what she had to do next…

Cain’s classic novels—Double Indemnity, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Serenade (there was an edition of this with a particularly fine cover)—all dealt with perfectly nice people who ended up in hellish nightmares, inexorably propelled there by their passions.

And that was what had happened to Cordelia.

Admittedly, her passion was for acquiring rare vintage paperbacks… But nevertheless. Here she was.

As the intensity of the storm grew and the keening of the wind became ceaseless, she looked at the dead man.

She didn’t want to get any nearer to him.

She didn’t want to touch him.

But she was going to have to.

It really was quite unfair.

1: FORGERY

It had all begun some weeks earlier with Cordelia standing outside her house, thinking, rather tensely, that the first thing she had to do was get back inside unseen.

Cordelia should never have gone out, but she’d needed quite urgently to scoot down into the village to obtain, of all things, a fountain pen.

The local bookshop had turned out to have one in stock. Luckily. The pen was in her hand now, a Lamy 2000, cool and elegant. It hadn’t been particularly cheap, but once she’d decided to buy one, Cordelia decided she had to have a good one.

Previously, whenever she’d needed a fountain pen—and she did occasionally need one for her work—she’d always borrowed Edwin’s. Naturally, Edwin owned a fountain pen. It was all of a piece with his Rohan corduroy trousers, his bicycle clips and his unseemly addiction to the Guardian crossword puzzle.

Cordelia stood outside the house now, some distance away, at the corner.

The challenge was to get back inside without Edwin seeing her. The trouble was, he could be sitting or standing in direct line of sight of at any of the downstairs windows or, much worse, might actually be outdoors.

Cordelia’s heart sank at the thought.

Edwin outdoors.

In the garden, or perhaps in the entranceway. He could be pretty much anywhere depending on the time of day and the available light. Working on his beloved bicycle.

Edwin had a special kind of steel frame device for working on his bike.

Of course he did.

The frame looked like a cruelly emaciated robot on which the bicycle could be mounted, the starving robot clutching it, making the bike easier to repair or maintain or pimp, or whatever stupid boring things stupid boring Edwin did with his stupid boring bicycle.

Cordelia eased forward on the pavement. She might be fretting for nothing. She couldn’t actually see any sign of Edwin outside the house…

But at this distance and at this angle, Cordelia’s view wasn’t ideal and there were a number of places where Edwin and his reprehensible bicycle frame could be lurking in concealment.

She couldn’t see enough of the front garden. And, to see more, she would need to get nearer and put herself in a position to be reciprocally spotted by the al fresco cycle mechanic. The hypothetical al fresco cycle mechanic. Cordelia hesitated. Get nearer and potentially expose her presence to Edwin, or wait?

But wait for what?

And she didn’t have much time. Cordelia realised that she was fondling the pen like some kind of talisman. She put it away and checked the time again. If she got into the house now and set to work, everything would be fine. Wait any longer and things would begin to get problematical. Really quite problematical.

Cordelia hesitated. Should she make a dash for it? There was no sign of Rainbottle.

That was promising. There was no way Edwin would be outside except in the company of his dog.

And vice versa.

Rainbottle was a rather agreeable auburn mutt—perhaps in a bid for camouflage, he was approximately the same colour as his master’s cherished corduroys (Ash Brown). The dog was certainly much preferable to the owner. But Rainbottle was disposed to lying quietly dormant, out of sight but vigilant, his tail occasionally swatting back and forth while, from concealment, he watched his master tenderly ministering to his cherished velocipede.

The dog worshipping the man, the man worshipping the bicycle.

So just because there was no sign of either of them, there was no guarantee they weren’t there.

Shit.

Cordelia needed to make a decision and move. She had to move now.

But if Edwin spotted her—

And then Cordelia saw the cat.

It was next-door’s ginger tom, somnolent and surly and much given to taking a dump in Edwin’s rose beds. (Clever little cat.) It had just emerged from under the gate of next door, oozing its corpulent form beneath the wrought-iron structure with impressive ease and then making a beeline for Edwin’s house and those very rose beds.

Cordelia moved forward with matching swiftness, jubilant, silently thanking the crafty little crapper. There was no way this providential puss would approach their house if Rainbottle was outside.

And if the dog was indoors, then so was Edwin. The two were inseparable, dog virtually invisible against those trousers.

Which just left the windows to worry about. Being spotted from the windows.

Cordelia darted forward, ducking into the concealment of the waist-high whitewashed wall at the front of the house. She was bent down because if she straightened up, she would be clearly visible to any potential Edwin in any downstairs room. But straighten up she must.

Cordelia raised herself with judicial caution to peer over the lip of the low wall.

Edwin wasn’t in the front room, so the coast was clear. Cordelia got up and opened the gate, a pale green wooden thing with an art deco sunrise carved into it. The hinges of the gate tended to squeak but Cordelia periodically spritzed them with a fine lubricating oil purloined from Edwin’s bicycle maintenance kit, in mind of just such occasions as this.

Congratulating herself on her foresight, she opened and closed the gate silently behind her, moving swiftly and noiselessly across the black-and-white-tiled garden path.

Her key went into the front door, also silently—more farsighted lubricant spraying of a mechanism with the residue of dead dinosaur—and Cordelia eased it open, slipped inside, and closed it behind her without a sound.

There was no danger of Edwin hearing her footsteps in the front hall thanks to the sound-deadening qualities of the hateful red and yellow ethnic rug that extended like a very long and very diseased tongue from the landing upstairs all the way to the front door, its final unfurling presenting itself lapping at the feet of unwitting visitors. Cordelia stepped inside the red hallway.

Not only was the interior of the hallway painted red, so was the upstairs landing and the staircase itself. Edwin had eccentric ideas about interior design.

Up the stairs she went, moving slowly, despite the urgent need to get into her room and get to work, because there were a number of hazard areas on the ascent, where if you put your foot down, the wooden staircase complained.

Indeed, even the lightest pressure would create a loud, agonising creaking that would inevitably bring Edwin out of his lair at the back of the house, like a lamprey lunging on its prey. A lamprey in Rohan corduroys.

But luckily Cordelia knew these danger spots by heart. So, treading carefully, she moved up to the landing with the loo on it, and then up the remaining section of staircase to where she finally stood now, safely outside the door of her attic room. Cordelia opened the door, went in, and was mildly disgusted with herself to find that she’d broken out in a sweat.

Quite apart from everything else, it was undignified.

Having to hide from one’s landlord.

But the fact was, Cordelia was late with this month’s rent; and if Edwin pressed her for it, she simply didn’t have it. Or rather, she had had it, but had spent it on other things. Better things.

She’d been compelled to spend it on other, better things.

Compelled by the fact that spending it that way was so much more fun than paying the rent.

But with a bit of luck, funds were about to be topped up. Topped up to such an extent that even Edwin might get paid.

Cordelia took out the fountain pen. It was black and silver and felt heavy and reassuringly well engineered, as it ought to, considering the price, an appreciable fraction of the rent she no longer had.

But Cordelia hoped the pen would soon pay for itself. And more besides.

Some years ago, Cordelia had been amused to discover an esoteric fact from the byzantine world of book dealing. Of course, she always known that any handwriting by a former owner in a book tended to lower the price of that book. So far, so obvious…

And, infuriatingly, it seemed there was always some abhorrent klutz who thought it acceptable to despoil a beautiful first edition with some repugnant personal message that permanently and significantly reduced its value.

Unless it was written in fountain pen.

That’s right: if it was written in fusty old fountain pen and not a dreaded modern pen, be it ballpoint or fibre tip, so long as those abominations were avoided, then, thanks to some deep-rooted retro snobbery in the rare book trade, it was deemed to be okay.

An inscription in fountain pen was as good as no inscription at all.

Cordelia had had occasion to take advantage of this piece of arcane lore a number of times in the past when she’d come across a rare and valuable paperback, pristine but for the fact that some bastard had written in it. These memoranda were inevitably penned with some unacceptable modern writing implement.

So, Cordelia took a fountain pen—up until now she’d borrowed Edwin’s—and painstakingly wrote over the price-lowering inscription, rewriting it, lovingly following its contours, saturating the old skeleton of the handwriting, until it looked like it had always been written in fountain pen.

And suddenly, voila, the book was back up to its full market value.

Fountain pen in hand, Cordelia moved to the large table where half a dozen neat stacks of paperbacks waited, competing for space with her dining area.

The paperbacks were all stuff she could sell, including some nice items—an immaculate Tom Wolfe Panther with a Philip Castle cover, to name one—but nothing to get particularly excited about.

Except for the Quiller.

Quiller was a mononymic secret agent who had been a rival of James Bond, George Smiley and Len Deighton’s nameless operative from the 1960s. Vintage Quiller paperbacks in exemplary condition, which was the kind of condition Cordelia tried to deal exclusively in, would always fetch a few quid. Except for the last novel in the series, which had become dramatically rare.

And was now priced accordingly.

Over the years Cordelia had found a number of copies, often in quite dodgy condition, yet she had always flipped them at a considerable profit. Then just last week she had found one in a charity shop in Chiswick in spectacularly good shape. In top or, as the book trade put it, fine condition.

She would easily be able to sell it for fifty times what she’d paid for it.

But… hubris…

That hadn’t been quite good enough for Cordelia.

She’d got to thinking how much more she might be able to sell the book for if it had also been signed by the author. Of course, it hadn’t also been signed by the author. But that had never stopped her before.

So, she had borrowed Edwin’s fountain pen. Because Cordelia had also now standardised on using that whenever she was going to create the one kind of handwriting in a book that could be guaranteed not to lower its value. Quite the opposite…

Which was to say, an inscription by a famous person.

Or more simply, the signature of the author.

Many was the time Cordelia had counterfeited an author’s signature using a good old fountain pen. Edwin’s good old fountain pen.

And so, when she got the Quiller book, it was inevitable she would jack the price up by making it another putatively signed copy. So, with Edwin’s pen she had set to work painstakingly, sitting in the good daylight of the bay window seat that was her favourite thing about her attic room and, in brutal truth, its only redeeming feature.

Cordelia had been very proud of the job she’d done that day.

But the ink had hardly been dry when she’d gone back online to gloat over her accomplished penmanship and confirm what a splendid forgery she’d achieved…

And indeed her work had been perfect. The signature was utterly convincing. But while establishing this gratifying fact, she also made a horrible discovery.

The book she had just signed had been published posthumously.

Oh fuck.

She’d just signed the author’s name in a book that was printed some fair while after the author had departed this world.

Oh fuck.

Instead of meticulously increasing the value of her acquisition, she’d just saddled it with the most obvious of forgeries.

Now, if she went ahead and sold the damned thing, it could start people wondering about all the other rare, signed paperbacks she’d flogged. People might start thinking she was a shameless and systematic counterfeiter, underhanded upgrader and an all-around sharp operator.

All of which, of course, she was.

And if her reputation went south, so would the price Cordelia could command for the books she sold.

There was only one thing for it.

Turn the signature into an inscription.

And to do that seamlessly and convincingly required a fountain pen. She couldn’t borrow Edwin’s because with his landlord hat on, so to speak, he would be eager to talk to her about the small matter of her outstanding rent. Or not so small matter. Certainly not so small in Edwin’s mind. What passed for his mind. Hence the Lamy.

Cordelia confirmed what she knew—that the colour of the ink in her new pen precisely matched Edwin’s—and proceeded to write inside the book.

A few seconds later, what had been a lone, bogus signature—Adam Hall—had become part of a respectful inscription. The last novel by the great Adam Hall. Cordelia added the dates of the author’s life, inspected it, and set it aside, satisfied. What had once been a blatant forgery was now a rather touching memorial. In fountain pen.

And the book was saleable.

Again.

Thank fuck. Thank goodness. Thank fucking goodness.

2: BOOK HUNTING TERMS

It was considerably easier sneaking out of the house than sneaking in, because Cordelia had been able to formulate a pretty good idea of Edwin’s whereabouts, having stood on the landing listening carefully for some five minutes.

She’d thereby established that her landlord was in his little sitting room at the back of the house. She’d concluded this from the occasional sound of movement—up from the armchair and across to the biscuit tin on the sideboard; Edwin deliberately kept this on the other side of the room to enforce a kind of rationing on himself—and back to the armchair again, biscuit craving temporarily abated.

Edwin was thus occupied, safely ensconced there in his bijou sitting room with Rainbottle, probably most of the time with his feet in his sensible woolly socks comfortably propped up on the back of the dog reading the cookery section of the Observer. Edwin, not the dog. If past form was anything to go by.

And anyway, even if he did hear Cordelia, so long as she moved briskly he wouldn’t be able to get to the front door in time to engage her in any form of conversation; in particular, in any form of conversation that would lead them by a very circuitous route but with a maddening inevitability, like a labyrinth in a Borges story, towards the destination of having a discussion about her being late with the rent. Really quite late.

But Edwin didn’t hear her, and Cordelia was out the door, down the steps and into the street.

Outside in the crisp fresh air and the autumnal chill, she paused to look back at the house.

Astonishingly, she had lived here for three years now, pretty much ever since she’d left university, with the degree in English literature which her mother had rather unkindly characterised as “About as much use as tits on a pterodactyl.”

(As a leading palaeontologist and a recognised authority on the neurobiology of the reptile–avian transition, her mother was in a position to know.)

Cordelia’s mother, and her passive, shiftless and ever-acquiescent father, had struck a deal with Cordelia whereby they’d pay off her student loan if she agreed to move out of the family home. And, it was strongly implied, never come back. This was just fine with Cordelia. She had then gone through a sequence of varyingly seedy flat shares before she’d had the good luck and good judgement to secure Edwin’s attic.

It hadn’t been easy finding a room to rent which could safely accommodate her collection.

Her beloved paperbacks.

It had been while at university that the paperback bug had bitten Cordelia. During one spring break she had gone to Amsterdam for the obvious reason but discovered to her astonishment that it had more to offer than dope cafés. And she didn’t mean the picturesque canals or flower markets or brothels.

It transpired that Amsterdam was probably the world centre, certainly the European centre, for the vintage paperback trade. Cordelia had accidentally wandered into a street market where there was a stall selling what she would later realise to have been a really first-rate selection of rare and desirable items. The lurid covers had immediately attracted her, with their exotic aura of a lost and distant era that was at once more innocent and more depraved than her own.

The one that really did it for Cordelia was the Bantam edition of Hal Elson’s Tomboy with the James Bama cover. She had always been a devotee of crime fiction, and this was a key text in the “JD” or “juvie” (juvenile delinquent) crime subgenre of the 1950s, which found its apotheosis, or its nadir if you were Cordelia, in West Side Story.

Hal Elson, who turned out not to be a pseudonym for Harlan Ellison, later to become another paperback favourite of Cordelia’s, could tell a strong story.

But it was the cover art that hooked her…

A teenage tramp with dirty blonde hair very like Cordelia’s was leaning against a wall with a cigarette negligently held in one hand, her entire posture a sexual challenge, leather jacket falling open to reveal the aggressive jut of her belle poitrine in a clinging brown sweater. Also on show were a pair of tight, rolled-up blue jeans displaying the artist’s incredible mastery of the depiction of fabric texture. The masterstrokes, though, were the dirty sneakers on the girl’s bare, sockless feet and the sardonic, knowing defiance on her feral babyface.

This little paperback book was absurdly expensive and not in perfect nick (she had subsequently long since upgraded to a treasured copy in fine condition), but Cordelia had to have it. She’d spent all the remaining money she had earmarked for binging in the hash cafés on buying Tomboy and then picking up from the same stall, for a modest additional increment, The Book of Paperbacks, a crucial reference work featuring some amazing colour reproductions of classic covers, written by Piet Schreuders, a local lad.

And once she started dipping into Schreuders’s book, that had been that.

Cordelia had found her calling.

Now she hurried happily along, her jaunty newish red rucksack bouncing on her shoulder. A cool clean breeze flowed in from the direction of the river and the rucksack patted Cordelia on the back as she walked.

It was a light pat because it was mostly empty, the rucksack, since she was planning to shortly fill it with books. With a lavish find of rare paperbacks.

Corresponding to the happy patting on the outside, Cordelia felt a happy pulsing inside that was the pleasurable anticipatory excitement she always experienced when she was on her way to a book sale.

This one started in a few minutes and was at the local church, St Drogo’s. It was to be a grand sale of old paperbacks with the proceeds going to repairing and maintaining St Drogo’s early-twentieth-century Bauhaus roof, the perpendicular purity of which was said to evoke Gropius, but which was also acknowledged to let the rain in, and leak a lot. Really quite a lot.

Cordelia didn’t give a shit about the church’s early-twentieth-century Bauhaus roof, or indeed the entire school of Gropius. What she was interested in was the healthy torrent of books donated by the local churchgoing community, many of which would be of exactly the vintage, and hopefully the genre, in which she was most interested.

In other words, lurid crime paperbacks of the 1950s and ’60s.

The more lurid the better. Visions danced in her mind. Immaculate copies of green-spined Corgis with John Richards covers, Carter Browns with Robert McGinnis art, preferably the original Signets, but some of the international editions were nice, too. Or, most especially, some British Sleuth Hound titles, with their fabulous Abe Prossont covers.

Cordelia was by now frankly addicted to collecting these, and their ilk.

But like many an addict-turned-dealer, she had found a way to support her habit. And, indeed, turn a profit. Which was how she came to make a living—of sorts—hustling vintage paperbacks.

Which was why she was now hotfooting it through Barnes towards the white and green blocks of that miniature Bauhaus masterpiece of ecclesiastical architecture, St Drogo’s—those flat roofs really did let in the rain, though, and repairs weren’t cheap. Someone—Cordelia’s face twitched into a smile as she hurried along—someone had suggested that one way of raising funds for the church roof would be by holding a sale of paperbacks.

As Cordelia crossed the road by the Sun Inn, a sleek silver car, spilling sunlight, came swooping towards her, moving fast, from the direction of the rather complex traffic junction by the duck pond.

Cordelia was compelled to jump back out of the road, onto the pavement, out of the path of the vehicle.

True, she hadn’t been looking where she was going, and she’d been in a considerable, some might say reckless, hurry. But, nevertheless, she turned to the car, looking to make eye contact with the driver and give him a good thorough cussing.

And she saw that the driver wasn’t a him, but rather a her.

And not just any her. Her. The Woman.

Eye contact had been made and it was like someone had thrown the switch on the electric chair. But in a good way. An electrifyingly good way. At least, that’s how it was for Cordelia…

With the Woman looking out at her from the silver car, window buzzed down, an expression of sincere concern and contrition on her face. Her face, her face.

Her lovely face.

The deep copper tone of her skin contrasted so wonderfully with the silver fuselage of the car that it took Cordelia’s breath away.

“I’m so sorry,” said the Woman. “I was going too fast. It was entirely my fault.”

Cordelia stared at her, still rendered breathless, still unable to formulate a single syllable. And then, with a wrench of desperation, she recovered the power of speech. And uttered this deathless soliloquy: “That’s okay. No problem!”

“Sorry,” said the Woman again. And she smiled again. And then she drove off.

Cordelia stared after her, cursing herself.

That’s okay. No problem!

How brilliant. How witty. And the rising, emphatic, cheery inflection on “no problem”…

What magnificent words for her to have used to sanctify the occasion. This sacred occasion – sacred wasn’t too strong a word. It was the first time the Woman had ever spoken to her. The first time she’d spoken to the Woman.

Cordelia had always regarded herself as pretty damned good looking. But whenever she was in the vicinity of the Woman, she felt herself disclosed as a snaggle-toothed, wall-eyed frump. Probably with flies circling her. A stupid shallow grinning white girl with dishwater blonde hair which she hadn’t even bothered to brush this morning.

The Woman, in contrast, loomed in Cordelia’s mind as composure personified.

The Woman had been cool and beautiful and kind and amused and penitent. Of course she had.

And she had smiled, smiled, smiled that smile…

Cordelia stared after her. The Woman had completely vanished now, but Cordelia gazed in the direction the car had gone, the shiny silver car. Hoping that it might do a U-turn and come back. She tried to make this happen, to bring the situation about by sheer willpower. She tried to visualise the car coming back. They did say visualisation worked, didn’t they?

Hurrying footsteps behind her on the pavement brought Cordelia back, at least partially, from this reverie. Someone was approaching her, gaining fast, then was beside her, then was abruptly brushing past her in a negligently rude and brusque fashion. Cordelia only glimpsed this person out of the corner of her eye as he shouldered her to one side, but an all-too-familiar aroma of body odour intruding on her nostrils was more than enough to convey his identity.

The Mole.

Well, there was a book sale, so of course the Mole was here.

Unlike Cordelia, the Mole didn’t specialise. Whereas Cordelia was obsessed (not too strong a word) with paperbacks, the Mole was obsessed (not too strong a word) with books in general. Large lavishly illustrated glossy hardcovers about the history of steam engines were as likely to go into his rucksack as—may he never find them, or at least never find them before Cordelia—vintage Boardman Bloodhound crime paperbacks with Denis McLoughlin covers.

The Mole knew what had value, and if he found such before Cordelia, he would scoop it up.

Cordelia watched the Mole’s stocky, bent back hurrying away, garbed in his traditional Mole garb of waxed cotton jacket and jeans.

Cordelia had known the Mole, or known of him, for as long as she’d been collecting books, which was as pretty much as long as she could remember.

Whenever she turned up at a jumble sale or boot fair or, as in this case, a church sale, there he would be hurrying to get in first, the Mole. Obsessively searching through the books and snapping up bargains, greedily gobbling up the best titles and, as Cordelia later learned, reselling them at a smart, sometimes eyewatering, profit.

In short, a rival.

The thought of this rivalry brought Cordelia the rest of the way out of her fantasy of the Woman in the car.

The accursed Mole.

Cordelia scooted.

She hurried across the road, once again not bothering to look out for approaching cars. Once again displaying the sort of flagrant disregard for traffic safety that had already almost got her run over by the Woman.

Wait.

Of course.

Of course, she realised, that was why the Woman was here.

The book sale.

She had come in search of vintage paperbacks, too.

And if she’d found somewhere to park her sleek silver car close to St Drogo’s, then the Woman was probably already at the front of the queue that had now begun to form. Whereas Cordelia, despite arriving on the scene well before the sale was officially due to start, nevertheless found herself near the back of that queue. She couldn’t believe it…

Cordelia was still a long way from the church and yet there was already this line of people stretching in front of her, people in their droves, ready, eager and willing to buy books. Many of them people who could probably actually read. And all of them obviously loving the prospect of a bargain.

The riverside suburb where Cordelia lived was inhabited by some of the richest people in London, and indeed featured a sprinkling of some of the richest in the world. Yet a myriad of these locals had turned out on this bonny autumn afternoon in search of cheap books.

But then it had always been Cordelia’s observation that no bastard likes a bargain better than a rich bastard.

It proved to be a long slow wait in the queue—in actuality it was less than five minutes, but it felt like an eternity, and indeed in book hunting terms it might as well have been. Because by the time Cordelia got inside, it was all over.

3: SAINTED NOT STAINED

The entire floorspace of the communal central area of the church of St Drogo’s was given over to the book sale—ranks of paperbacks conveniently arrayed spine-up in shallow crates for easy perusal (at least, by the literate), on long trestle tables.

This big space packed with tables, all covered with books, was pretty much Cordelia’s idea of heaven. So a church was certainly an appropriate setting.

Or at least it would have been her idea of heaven if it wasn’t already writhing with a crowd of bibliophile bargain hunters who had arrived before her.

All presided over by an enormous stained-glass window occupying virtually an entire wall of the central atrium of this Bauhaus masterpiece, a rectangular shaft rising fully three floors through the hollow heart of the building, all the way to its famously problematical roof.

But by the time Cordelia had got in here, with that big window looming balefully over her, all the good stuff had gone.

Cordelia was too late, or rather not early enough, and consequently she was getting a look at the way a book sale would appear to your average punter, the customers who never knew what treasures, what bargains, what bargain-priced treasures, surfaced at such events.

Because such gems are all always snapped up in a few crucial seconds after the doors were opened.

And Cordelia hadn’t been here for those few crucial seconds.