Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

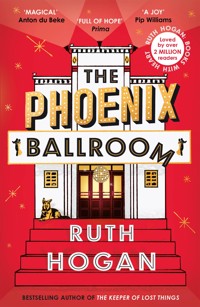

THE BRAND NEW UPLIFTING NOVEL FROM THE AUTHOR OF THE TWO-MILLION COPY BESTSELLER THE KEEPER OF LOST THINGS 'Magical ... uplifting ... the Phoenix Ballroom feels like an old friend' ANTON DU BEKE 'A rich and joyful story, told with wit and heart' BETH MORREY 'Every page is a joy' PIP WILLIAMS ITS NEVER TOO LATE TO SPREAD YOUR WINGS... Recently widowed Venetia Hamilton Hargreaves is left with a huge house, a bank balance to match and an uneasy feeling that she's been sleepwalking through the last fifty years. Buying the dilapidated Phoenix Ballroom and with it a community drop-in centre could be seen as reckless, but Venetia's generosity, courage and kindness provide a refuge for an array of damaged and lonely people. As their stories intertwine, long-buried secrets are revealed, missed opportunities seized and lives renewed - the Phoenix lives up to its name. 'Will enthral and delight everyone who reads it' MIKE GAYLE 'Packed with Ruth Hogan's trademark warmth' MATT CAIN

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Readers love The Phoenix Ballroom

“What a well written and beautifully woven tale, of kindness and supporting others and the happiness that this can bring”

“Ruth Hogan has done it again…another book that grabs you from the start”

“A real heartwarming tale and a captivating read”

“Another wonderful, uplifting and utterly lovely book by Ruth Hogan”

“Put the kettle on, curl up and lose yourself in this chocolate box of characters”

“A book to read and comfort yourself on the gloomiest of days”

“Brought me back to my great love, and I think that was due to the extraordinary writing…no one like her out there”

“The richness and quality of the writing is so beautiful – a bit like finding a box of really expensive chocolates and savouring them one by one!”

“I galloped through this book so quickly that I’m annoyed with myself for not savouring it”

“Ruth Hogan’s Keeper of Lost Things is one of my all-time favourite books to be read and re-read, and I think The Phoenix Ballroom has just joined it!”

“I was so engrossed with the storyline I just couldn’t put it down”

“Everything she writes is worth every inch of type space. Bravo Ruth”

“How I loved this book, once I began it, I couldn’t stop reading it, even though I wanted it to last, and that doesn’t happen too often!”

“This truly is an uplifting and emotional read”

“This is a heartwarming read populated with characters who will stay with me”

“Love Ruth Hogan, love literally ALL of her books! Without exception”

“A nice heartwarming story about second chances”

“Her books have become real favourites of mine”

Praise for The Phoenix Ballroom

“The ballroom is a magical place, and Ruth Hogan’s love and warmth for all the things within it shine brightly in the pages of this wonderful story. She has created such an uplifting world, and the Phoenix Ballroom feels like an old friend of mine” – Anton du Beke

“Pulsing with life, hope and full of characters that leap off the page and straight into your heart” – Mike Gayle

“A delightfully uplifting novel” – Woman’s Own

“Kindness, courage and charm aplenty…connections and conundrums drive a story that thrums with understated sensitivity” – Mail on Sunday

“Packed with her trademark warmth, populated by vulnerable characters she once again brings to life with sensitivity, and is bursting with dark secrets, unresolved tensions and unexpected plot twists – but this time it has added social commentary and takes a great big bite out of the zeitgeist!” – Matt Cain

“A gorgeous book that made me feel better about the world. It is comforting, captivating and beautiful.” – Eithne Shortall

“Hugely compelling…a wonderful read” – Kit Fielding

“Another gem from the queen of heart-filled storytelling, The Phoenix Ballroom is an enchanting tale of community, friendship and acceptance, illuminating the joys of living your life as your own true self whatever your age…A hugely entertaining read.” – Sarah Haywood

“Love, friendship and compassion abound – every page is a joy.” – Pip Williams

“A lovely, life-affirming story…poignant and inspirational, the novel has at its heart a promise: whatever has gone before, lives can change. I loved it.” – Elizabeth Buchan

“A sparkling, intensely moving story that sweeps the reader along. Full of hope, love and the power of new friendships.” – Celia Anderson

“A rich and joyful story told with wit and heart…look out for this sweeping waltz of a novel.” – Beth Morrey

“Ruth Hogan’s latest will make your heart soar and your eyes tear up…The Phoenix Ballroom is an uplifting novel filled with wit, heart, and humour and is as satisfying as a turn around the dance floor.” – Janet Skeslien Charles

Ruth Hogan studied English and Drama at Goldsmiths College and went on to work in local government. A car accident and a subsequent run-in with cancer convinced her finally to get her act together and pursue her dream of becoming a writer. The result was her debut novel – The Keeper of Lost Things, which went on be a global bestseller. She is now living the dream (and occasional nightmare) as a full-time author, along with her husband and rescue dogs in a rambling Victorian house stuffed with treasure that inspires her novels.

For more information and updates, follow her on Facebook @ruthmariehogan, and on Instagram @ruthmariehoganauthor

Also by Ruth Hogan

The Keeper of Lost Things

The Wisdom of Sally Red Shoes

Queenie Malone’s Paradise Hotel

Madam Burova

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Corvus

Copyright © Ruth Hogan, 2024

The moral right of Ruth Hogan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 073 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 072 5

Printed in Great Britain

Design benstudios.co.uk

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Title

Copyright

Once Upon a Time …

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Acknowledgements

Landmarks

Cover

Title

Start

To Ancients of Moo Moo

‘Blessed are the cracked, for they shall let in the light’

Attributed to Groucho Marx

Once Upon a Time …

The ballroom was a sleeping beauty waiting for the kiss of life. After years of neglect, the floor was velveted with dust that lay undisturbed save for the feather-light tracery fashioned by resident mice. The once-bright stars that studded the indigo ceiling were now a ghostly constellation barely visible beneath the dirt, and the art deco chandeliers were choked with cobwebs. Along one wall tall mirrors hung in a line, but the glass in each was mottled; a metallic leopard print that threw back only a scattered mosaic of imperfect reflections. A dozen or so chairs stood moth-eaten and forlorn around the edges of the room, like wallflowers waiting for an invitation to dance, but the piano in the corner was silent, its keys sticky with damp. Dead flies freckled the sills of the windows where faded curtains still hung, ravaged by moths. But outside, as the sun slipped down behind the rooftops of the town, its fiery light caught crystal from a chandelier and ricocheted a rainbow across the ballroom floor.

Up on the roof, Crow watched ribbons of gold and purple light bleed into blackness and the moon swap shifts with the sun.

Chapter 1

Venetia Hamilton Hargreaves wondered whether sandwiches and sausage rolls might have been a better choice than canapés as she waited for her husband’s corpse outside St Paul’s Church. It would soon be lunchtime and surely people would prefer something more substantial than a sliver of smoked salmon on a cracker smeared with cream cheese? Well, it was hard cheese now. Too late to change. The air was heavy and humid, and a heat haze shimmered off the gleaming black paintwork of the hearse. A storm was forecast. The coffin was crowned with an elaborate spray of lilies and ivy, and the blooms trembled with every step the pallbearers took as Venetia followed them down the aisle; the same aisle that she had walked as a bride, carrying freesias and lily-of-the-valley on the arm of her handsome groom almost fifty years before. A sad but somehow satisfying symmetry. This time she had her son at her side. It had been her son, Heron, who had insisted on canapés, specified the champagne, and booked the hotel where both were to be served after the service. Venetia’s suggestions had been swatted aside because Heron had assured her that he ‘knew best’. He had even chosen her outfit, and she had let him have his way. For now. He took his place beside her in the front pew as the coffin was set down on trestles before the altar. His face was red with the effort of containing his emotions and he clutched a meticulously folded handkerchief in his fist in case eventually he should fail. Heron was an unfortunately comic misnomer for one so deficient in stature and grace, but his grandfather had been a keen amateur ornithologist. He had named his children Hawk, Osprey, Nightingale and Swan, and his sons had continued the practice with their own offspring. With his scarlet cheeks and tubby torso, poor Heron looked more like a crotchety Christmas card robin. Venetia placed her hand on his arm and gave it a gentle squeeze. She felt him tense at her touch and returned her hand to her lap. In contrast to her son’s discomfort, Venetia was surprisingly sanguine for her public debut as a widow. She would miss her husband, of course she would, but in the way that one misses a comfortable cardigan that has shrunk in the wash and become too tight to wear.

The church was almost full. Hawk Hamilton Hargreaves had been a popular and well-respected man, and he would have been gratified to see such an impressive turn-out for his last hurrah. He had chosen the order of service himself and Venetia was grateful. It had saved her the worry and she was glad for him that he was getting exactly what he wanted. After welcoming the congregation with respectful solemnity, the vicar announced the first hymn and as they stood to sing ‘Jerusalem’, the small boy beside Venetia clattered to his feet, dramatically brandishing his hymn book in both hands. Kite was Venetia’s ten-year-old grandson, and this was his first funeral. He was clearly enjoying the occasion immensely and sang with gusto, his dark curls bouncing as he nodded vigorously in time to the music. A growl of thunder added an impromptu percussion accompaniment to the organ and Kite’s eyes widened with delight. The front-pew line-up was completed by his mother, Monica, who was a born-again atheist and had made it clear that she was only there to keep up appearances. When the congregation sang ‘Bring me my spear, O clouds unfold’, their command was seemingly obeyed as a bolt of lightning flashed and forked behind the largest of the stained-glass windows, showering its rainbow colours onto the altar.

The rest of the service was conducted in competition with the storm and was, at times, all the better for it. Heron’s eulogy to his father – touching and sincere in sentiment but a little dull in its delivery – was much enlivened by cracks and booms from the heavens above. Swan, sister of the deceased, wearing a velvet opera coat and a black net veil attached to a jewelled Alice band, recited the Henry Scott-Holland poem about death being nothing at all and the person having only slipped into the next room. Having forgotten to renew the batteries in her hearing aids, Swan spoke at a volume that not only could be clearly heard above the thunder, but was probably audible in the next street. Kite struggled valiantly to supress his giggles until Monica silenced him with a scowl. Venetia caught his eye and winked at him consolingly. Prayers were said, ‘Abide with Me’ was sung, but it wasn’t until the final piece of music began to play that tears blurred Venetia’s eyes. Hawk had chosen Edward Elgar’s ‘Nimrod’ to mark his farewell. Of course he had. Dignified, tasteful, British. Achingly conventional. Exactly like himself. A decent, kind, respectable, slightly pompous man who had guarded his conventionality with his life. Literally. And Venetia couldn’t help wondering how things might have been if he hadn’t. But he had been the best husband to Venetia that it was possible for him to have been and for that she would be forever grateful.

Before leaving the church, Venetia approached the coffin and brushed her fingertips across the polished oak.

‘Goodbye, Hawk,’ she whispered. ‘Time to face the music.’ She hoped sincerely that he would dance.

Kite hovered behind her uncertainly. ‘Can I touch it?’ he asked.

‘Of course,’ Venetia replied.

Kite slapped both hands down on the lid of the coffin with a resounding thud.

‘Bon voyage, Grandpa! And don’t forget you said I could have your chess set!’

Outside, the storm had passed, and the air was clean and fresh. Sunlight glistened on the wet pavements. It was only a short distance to the hotel, and although Heron would have preferred them to travel in the limousine, Venetia insisted on walking.

‘The arrangement was that we should take the car,’ he chided her, clearly irritated at the deviation from his meticulously planned programme for the day. But Venetia held firm. She took Kite’s hand to cross the busy main road and set off towards the town’s Victorian embankment in her smart but sensible low-heeled, much-hated black court shoes. Within minutes they had reached the hotel and were met by a member of staff who told them that she was ‘very sorry for their loss’ and showed them through to a function room overlooking the river where the wake was to be held. A waiter offered Venetia a glass of champagne, which she accepted gratefully, and she took a large sip. Heron frowned.

‘Best take it easy with that, Mother,’ he warned. ‘We have a lot of guests to greet’ – the first of whom arrived before Venetia had a chance to reply. There followed almost half an hour of thanking people for coming and accepting their condolences, during which time the waiter discreetly refilled Venetia’s glass as necessary. It struck her once again that this was a strange echo of their wedding – the stream of guests and perfunctory exchanges with people ranging from family and friends through to acquaintances and even some, to Venetia at any rate, complete strangers. The last mourners to enter the room were two men whom she had never seen before. Heron thanked them for coming and excused himself before they could reply, his priggish sense of propriety finally exhausted, or perhaps simply usurped by the desire for a drink. But Venetia was curious. They certainly didn’t look like former colleagues of Hawk’s from the legal profession, nor did they resemble his usual brand of cronies who wore jumbo cords, had season tickets at Twickenham and Lord’s, and holiday homes in Scotland or Norfolk. The first of the two, a man of about Venetia’s age with grey hair and pale-green eyes, took her hand and instead of shaking it, simply held it between his own.

‘You must be Venetia,’ he said. ‘We were old friends of Hawk’s. We lost touch with him some years ago, but we thought of him often. I’m so very sorry.’

His sincere and concise expression of sympathy was spoken quietly, but with warmth and confidence, and Venetia was touched. Before she had time to respond, Kite appeared wearing a pained expression and waving a canapé, and the two men moved away towards a waiter serving champagne.

‘Nisha, what is this?’ Kite asked in a stage whisper, sniffing the canapé with exaggerated suspicion. ‘Why isn’t there any proper food?’

‘Nisha’ had been his earliest attempt at pronouncing her name and had somehow stuck.

‘It’s smoked salmon and cream cheese.’

Kite was unimpressed. ‘It’s all slimy. Aren’t there any sandwiches? I’m starving.’ He was still whispering, having been warned by his father to be on his best behaviour, but his grandmother was always his chosen ally.

Venetia smiled. ‘I’ll see if we can rustle up a bag of crisps.’ She spoke to one of the waiters and Kite was soon tucking into his favourite salt and vinegar snack.

‘Now that I’ve got you some crisps,’ she told him, ‘you can return the favour.’

He immediately offered her the packet. She shook her head.

‘No, I want you to come with me and chat to your great-aunts. I need a wingman.’

‘What’s a wingman?’

‘Someone who helps you out in tricky situations. Someone you can trust.’

Kite grinned. ‘Well, that’s definitely me. I’m your wingman. Mum says Nightingale and Swan are as mad as a box of frogs.’

Venetia glanced over to the window where her husband’s sisters were sitting surveying their fellow guests and downing as much champagne as they could.

‘That may be true, but they’re also family.’

‘I like them,’ Kite replied. ‘I like frogs too. But not to eat.’

Nightingale saw them approaching and waved them over.

‘How are you bearing up, my dear?’ she asked Venetia.

Venetia shrugged, hoping that that would suffice as the answer to an impossible question, but one that everyone kept asking her. She had no idea how she was. Her husband had died, and she had just attended his funeral. How was she supposed to be?

‘And how’s my great-nephew? Let me have a proper look at you.’

Kite stepped forward gamely, waiting for the inevitable ‘Haven’t you grown?’

‘Haven’t you grown? You look exactly like your father did at your age.’

Kite didn’t appear to be flattered by the comparison, but remembering his role as wingman, offered Nightingale a crisp. She declined – to his obvious relief.

‘It’s lovely to see you both. How was your journey?’ Venetia wondered how many platitudes they could exchange before Swan interjected.

‘Bloody awful!’ bellowed Swan. She had lifted the black veil away from her face and swept it back over her hair. She looked like a Halloween bride.

‘Oh dear! Was it the trains?’

‘No, not that! I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about dying! Bloody awful thing to happen!’

‘Grandpa was very old,’ ventured Kite.

‘I’m very old!’ Swan replied. ‘But I don’t want to bloody die!’

Kite offered her his crisps and she took a handful.

‘Now don’t upset yourself, dear. You’re years younger than Hawk was.’ Nightingale grabbed another two glasses of champagne and handed one to her sister. Swan swigged from her glass.

‘I’m not upset! I’m bloody furious! It’ll be us next.’

Venetia’s wingman stepped up once again. ‘It’s an empirical fact that women live longer than men,’ Kite announced. ‘So, it’s more likely that Great-Uncle Osprey will die first.’ Great-Uncle Osprey was standing at the bar looking perfectly well and drinking a whisky and soda. Meanwhile, Heron had joined them, anxious to find out what all the shouting was about and equally anxious to put a stop to it.

‘Is everything all right?’

‘No, it bloody well isn’t!’ boomed Swan. ‘We’re all going to die!’

‘But Great-Uncle Osprey’s going first,’ added Kite helpfully.

That evening, alone in her bedroom, Venetia stood at the window watching a pair of swans glide beneath the elegant arch of the suspension bridge. She recalled that swans mate for life (except her sister-in-law, who had never shown any inclination to mate with anyone) and Venetia too had pledged ‘till death do us part’. She had kept her promise. But what now? It had been a long day and she was exhausted. She kicked off her shoes and sat down on the bed where she had laid Hawk’s dressing gown on top of the covers on his side. They had their own rooms, largely due to their conflicting nocturnal habits. Hawk had snored like thunder and had fallen asleep as soon as his head hit the pillow, and Venetia liked to read or watch old films until past midnight. But they had still occasionally shared a bed and it had been comforting and companiable. Sometimes one would read aloud to the other, or they would attempt a crossword together. Sometimes they would simply hold hands and say nothing until they drifted off to sleep.

Catching sight of herself in the full-length mirror beside her wardrobe, she shook her head in disbelief. How had she allowed herself to become this old woman? At eighty-four, Hawk had been ten years her senior. He had been old and perhaps it had rubbed off on her like rust. But she wasn’t ready for that yet. She wasn’t ready to be old. She studied her reflection in dismay. Her grey hair was styled in a neat but unflattering bob, and the black crêpe-de-Chine dress that Heron had chosen for her was little better than an expensive sack. He had wanted her to stay with them for a few days. ‘It isn’t right that you should be on your own at a time like this,’ he had told her, but she had insisted that she would be fine. He had eventually relented but told her that he would be round first thing in the morning to check on her. Poor Heron. He always tried so hard to get things right. But right for whom? He worried far too much about what other people thought instead of thinking for himself. It had been hard for him today – Hawk hadn’t just been his father, he had been his hero. Venetia had told him that the day had been perfect – that his father would have been very proud of him. Heron had broken down and sobbed in her arms. He had spent his whole life trying to live up to his father’s example, but Venetia hoped that now he might discover that he could be his own man.

She drew the curtains and got undressed, folding the black sack and leaving it on the back of a chair. There was no point returning it to her wardrobe because she had no intention of ever wearing it again. The shoes were going in the bin. Suddenly she wasn’t tired any more. She pulled on Hawk’s dressing gown. The faint scent of Acqua di Parma, the cologne that he had always worn, still clung to the fabric. Downstairs in the kitchen, she took a bottle of wine from the fridge and poured herself a glass. It was getting dark, and stars were beginning to prick the evening sky. She raised her glass in a silent, affectionate toast to the man who had died, and vowed that her life was about to begin anew.

Chapter 2

Heron arrived too early the following morning, apparently keen to get something off his chest.

‘I’m arranging a live-in companion-cum-housekeeper for you,’ he announced, his tone clearly implying that his mother should be pleased. Venetia was appalled.

‘I don’t want a companion-cum-housekeeper! I can manage perfectly well on my own.’

Heron sighed. ‘Now, Mother, we can’t have you rattling around in this big house all alone. What if you were to have a fall?’

‘I’m perfectly fit and healthy. Why on earth should I have a fall? I’m not a toddler!’

‘Exactly! You’re an elderly lady who simply needs a little help around the house and someone to keep you company on outings – visits to the theatre and cinema and the like …’ he trailed off.

The word ‘elderly’ stung like a nettle.

‘For heaven’s sake, Heron! You sound like one of those advertisements for domestic staff in The Lady. I don’t need any help and I already have company for visits to the theatre and cinema and the like. They’re called friends!’

Heron flushed a little. ‘It’s completely understandable that you want to keep your independence, and surely this is the best way? Better than moving into some dreadful retirement village.’

Venetia laughed out loud in disbelief but was saved from saying precisely what she thought by the breathless arrival of Kite, who had been distracted on his way in, checking for ripe strawberries in the garden. The red stains on his fingers revealed that he had found some.

‘Did Dad tell you that he’s getting you a granny nanny?’

There was an awkward silence which Heron hurriedly filled.

‘I didn’t say that at all! I said that we were going to get Nisha someone to …’ he struggled to find an appropriately placatory phrase and eventually settled on ‘to help her out with … things.’

‘Mum definitely said that you were getting Nisha a granny nanny. I remember because I didn’t know that grannies had nannies.’

‘They don’t,’ Venetia replied pointedly.

‘I found some strawberries,’ Kite informed her. ‘Did Dad tell you that he and Mum are going to France and that I’m going to start as a boarder at school next term?’

‘No, he didn’t. But I’m sure he was just getting round to it.’

Venetia looked at Heron and raised her eyebrows expectantly. ‘Would anyone like tea?’

Kite’s face lit up. ‘If you’ve got any dead-fly biscuits then I would, please.’

Venetia smiled. ‘I think there’s some in the pantry. You go and have a look and I’ll put the kettle on. And then your father can tell me all about his defection to France.’

As they sat around the table, Kite dunked Garibaldi biscuits into his mug and Venetia watched her tea grow cold while Heron explained that he and Monica were opening a new office in the South of France and that they needed to be there for eighteen months or so to oversee the start-up. They ran a lucrative business selling holiday properties – Monica did the selling and Heron the conveyancing.

‘I appreciate that the timing isn’t ideal so soon after …’ Heron let his sentence tail away, unable to bring himself to say the words ‘Dad’ and died’ in such painful proximity.

Kite was fishing around with his finger for half a biscuit that was floating in his tea. Venetia passed him a teaspoon. Having regrouped, Heron continued.

‘I’m afraid it can’t be helped. We have to be in France by the beginning of September which is why I want to make sure that you are safe and well looked after before we leave.’

Venetia was tempted to remind him that she was the parent, and he was the offspring in their relationship, and that she was neither old nor infirm enough to warrant a role reversal just yet. But now, at any rate, his motivation was clear. The appointment of companion–housekeeper hybrid would enable him to depart to France with a clear conscience that he had fulfilled his filial obligations, despite his physical absence.

‘And what about you, Kite? How do you feel about boarding?’

Kite shrugged.

‘It’ll be fun! He’ll love it!’

Heron proclaimed it as fact rather than opinion, but Venetia knew that he genuinely believed it. Heron himself had been at boarding school from the age of eleven (against Venetia’s wishes, but she had been overruled by both her husband and her son) and had thrived, finding comfort and confidence within the confines of routine and conformity, just as Hawk had before him. He had enjoyed the camaraderie of the cricket and rugby teams, the rough and tumble of dormitory pranks, the swagger and zeal of the debating society and the sense of pride and achievement at prize-givings. His schooldays had confirmed rather than formed who he was. He had belonged. But Kite was different – in so many ways. Venetia worried that too many rules and expectations might bruise and chafe a boy whose character was still unfixed, and stifle his ability to choose his own place in the world.

‘He doesn’t have to board,’ Venetia offered. ‘He could live here with me and be a day pupil.’ She saw a glimmer of hope flicker in Kite’s eyes, only to be immediately extinguished by his father.

‘Nonsense! It’ll be good for him!’ Heron replied with that irritating jollity that parents employ to win over reluctant children.

Kite said nothing but Venetia could see that he was unconvinced. She wanted to fight his corner and insist that he stay with her while Monica and Heron were in France, but they were his parents, and while she could offer her opinion, only they had the right to make decisions concerning their own child. But she had thought of something that might make Kite smile.

‘I think we ought to go and fetch Grandpa’s chess set,’ she told him. ‘It belongs to you now.’

Heron had some ‘errands to run’ in town which would be completed more speedily without his son in tow, so he excused himself and departed, leaving a delighted Kite in the company of his beloved grandmother. The chess set was in Hawk’s study, a small room lined with bookshelves that led off the square entrance hall of the house. Venetia opened the door and she and Kite paused for just a moment in reverent silence before going in. This was the room where Hawk had died, dozing in his chair after a light lunch of Welsh rarebit followed by a small whisky and soda. The Times had been spread across his knees when Venetia found him – the crossword almost completed in his confident black scrawl. His fountain pen had fallen from his fingers and stabbed an ink stain into the carpet. The only unsolved clue had been 5 down – ‘Endgame’, 9 letters. This had been the mundane minutiae of Hawk’s death. Later that evening before going to bed, Venetia had completed the crossword for him: Checkmate.

‘It still smells like Grandpa,’ whispered Kite. Venetia drew back the half-closed curtains to let in the sunlight, startling glittering dust motes into the musty air. Her husband’s leather chair still bore the vestiges of his presence; indentations in the cushion where he had sat for so many hours, and patches on the arms polished to a shine where his sleeves had rested. This was the chair where a younger Kite had perched on his grandfather’s knee and listened to the adventures of Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit and the exploits of Richmal Crompton’s Just William. The chess set sat on Hawk’s battered mahogany desk in a small wooden box. It was a travel set made in the 1930s, which had originally belonged to Hawk’s father. The pieces themselves were cherry red and butterscotch yellow Bakelite, and Kite had loved to play with them long before he had learned the rules of the game. His grandfather had taught him the rudiments when he was eight and Kite had been addicted ever since. Venetia handed the box to Kite, who hugged it to his chest.

‘But who will I play with now?’ he asked, his eyes suddenly filling with tears.

‘Perhaps one of your new friends at school?’ Venetia suggested.

‘But what if I don’t make any new friends?’

‘Why wouldn’t you?’

Kite sniffed and rubbed his eyes with the back of his hand.

‘Because I’m not very good at that stuff. I don’t know the rules. I don’t know how to get people to like me.’

Venetia wrapped her arm around his shoulder. ‘Making friends isn’t like chess, sweetheart. There aren’t any rules, and you can’t make people like you. But I do know that anyone would be very lucky to have you as their friend.’

‘Or their wingman?’

‘Absolutely! You are an excellent wingman. And if you can’t find anyone else to play chess with you, then you can teach me how, and I will. Now, is there anything else of Grandpa’s that you would like to remember him by?’

‘Yes please,’ Kite replied. ‘Can I have his bow ties?’

Heron returned at lunchtime to collect his son and present Venetia with the book of condolences that had been signed by guests at the wake.

‘I thought that perhaps you could write to the people who came and thank them. It might be good to have something to keep you occupied and take your mind off things,’ he said as he handed it to her. Kite squeezed her hard in a hug and thanked her for the chess set, but his shoulders drooped as he followed his father out to the car.

Later that afternoon, Venetia sat in the garden watching the bees dipping in and out of the honeysuckle, their legs fuzzy with orange pollen. Her head buzzed with irritation at Heron’s revelations. Her first concern was for Kite. He was clearly unhappy at the prospect of becoming a boarder, but his father was far too engrossed in his fancy French business plans to notice. Kite had a quick mind, a kind heart and a couple of friends, but no reliable internal map when it came to navigating the ways of the world. For the most part, he lived on his own private planet. But at least Venetia would be his designated guardian as far as the school was concerned whilst his parents were abroad. She would be able to intervene if it became necessary. And as for the ‘granny nanny’ – what a damn cheek! Heron had actually called her ‘elderly’. At only seventy-four she was younger than Cher! She couldn’t imagine anyone having the nerve to call Cher ‘elderly’. But she had to concede that, in a way, it was her own fault. She had allowed herself to become subsumed by her marriage. She had finished up being the character she had, at the start, only played. She had become the supporting actor, never the lead – the directed, never the director. And that was how her son saw her and so assumed that she would be unable to cope on her own. What he failed to understand is that support requires strength. As a supportive wife, she had been the cornerstone of the marriage; the buttress that had kept their family solid. Hawk had been a traditional, head-of-the-household husband, but he couldn’t have managed that without her. She didn’t need a carer or a chaperone, but perhaps it might be useful to have some help around the house. After all – it was a big place for her to manage on her own. She knew that it would ease Heron’s conscience and it would certainly give her more time to pursue new interests and make the changes to her life that were long overdue. She wasn’t sure exactly what they would be yet, but she was pretty sure that Heron wouldn’t approve of them. But then Heron would be in France. And perhaps the granny nanny could write the thank-you notes to the funeral guests.

Chapter 3

Liberty Bell watched her mother’s coffin disappear behind the not-quite-velvet curtains of the municipal crematorium while the Edwin Hawkins singers belted out ‘Oh Happy Day’. Some of her mother’s friends from church were joining in. Some were even dancing. The rest of the mourners looked on with affectionate smiles. A few brushed away tears, but from the expressions on their faces they could just as easily have been attending a wedding rather than a funeral. Liberty felt hopelessly detached from everything that was happening around her – a spectator rather than a participant. She couldn’t quite believe that her mother had been in that box. Bernadette Bell had been a Technicolor tornado of a woman who had lived this life gleefully, vigorously and splendidly. And she had had no intention of going quietly into the next. She had chosen her own funeral director, left him with precise instructions and prepaid the bill. The arrival of her coffin had been accompanied by Shirley Bassey singing ‘Get the Party Started’. They had, to Liberty’s relief, also sung the more traditional ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ and said a few prayers before Liberty had delivered a dignified and loving eulogy to her mother. This was followed by a flash mob from the pews performing ‘This Is Me’ from The Greatest Showman – but without the waving of sparklers that Bernadette had requested. The crematorium had had to draw the line somewhere.

Outside, in brilliant sunshine, Liberty stood by a profusion of floral tributes, leaden with grief. A lone, grey figure in a kaleidoscope of colour. Bernadette had specified ‘No black’, but grey was as far as Liberty could permit herself to stray from the confines of convention. She allowed herself to be hugged and consoled by a handful of relatives and a seemingly endless stream of her mother’s friends. She smiled and nodded, agreed that the service had been exactly what her mother would have wanted, and yes – they’d been lucky with the weather, and yes – the flowers were beautiful. But what she really wanted to do was to tell them all to bugger off so that she could go home, down an obscene quantity of gin, eat her own body weight in chips and cry herself to sleep. She desperately needed the release of tears, but so far, they had resolutely refused to fall. She had inherited none of her mother’s carefree spirit and hoped that spirit of a different kind might help to unlock her frozen emotions.

‘Are you ready to make a move, darlin’?’

She felt someone take her elbow and turned to find her mother’s oldest friend, Evangeline, beside her. Evangeline guided her towards a waiting black limousine and climbed in after her.

The wake was held in a local pub just around the corner from the house that Liberty had shared with her mother. Bernadette had paid for a substantial tab at the bar and there were a great many increasingly rowdy toasts proposed and drunk in her memory. Liberty sat at a table in a corner nursing a large gin and tonic and a growing sense of grievance that she was incapable of truly participating in this glorious celebration of her mother’s life. Evangeline arrived at the table with a plate piled high with food from the buffet and sat down opposite her.

‘Have something to eat, sweetheart. You don’t want to be drinking on an empty stomach,’ she said, sipping from a tall glass of rum and Coke.

Liberty selected a sausage roll and bit into it without enthusiasm.

‘She’ll be missed at church, you know,’ Evangeline declared, and helped herself to a cheese and pickle sandwich from the plate. ‘But at least she’s with your father again now.’

And several other boyfriends that came after him but went before her, Liberty thought, wondering how that might work in the afterlife, if there was such a thing.

‘What are you going to do now?’ Evangeline interrupted her musings. ‘Your mother told me that you’d lost your job before she died. And no bad thing it is either! That man was never going to walk you down the aisle, girl! You’re worth a lot better than him.’ Evangeline kissed her teeth to emphasise her point.

Liberty chewed morosely and wondered how many more details of her personal life her mother had shared with her friend.

‘You sold yourself short with that married man,’ Evangeline continued, warming to her theme. ‘You’re a fine-looking lady and clever, too. You can get yourself another job and a proper gentleman friend in no time.’ She raised her glass towards Liberty and then took a serious swig.

‘You just need to loosen up a little.’

That evening Liberty sat in her mother’s courtyard garden, surrounded by wind chimes and Moroccan lanterns, sipping more gin and wondering how she had ended up with so little to show for her forty-six years on the planet. By the same age, her mother had enjoyed numerous interesting jobs – including working as a croupier in Cannes, nanny to the children of a famous British actor, driver for a viscount and viscountess in London, and personal assistant to a best-selling crime novelist. She had also clocked up several lovers, one husband, one daughter, a public disorder offence at an anti-apartheid march, and a beach hut in Brighton. Liberty had loved that beach hut, but her mother had swapped it on a whim one summer for a VW campervan. Bernadette had truly been a bohemian soul, and she had also been a loving wife and mother. But when her husband, Liberty’s father, had died five years previously she had grieved and then she had got on with life. For the last twenty or so years, she had worked as an antiques dealer, travelling to fairs all over the country and selling items online. She had flatly refused to retire, even when she was told that she was dying. Her defiant response to her consultant, her daughter and her friends had been ‘I intend to live right up to the moment when I bloody welI die.’ And she had. Propped up in bed in the local hospice wearing her favourite silk dressing gown and listening to Dolly Parton on her headphones.

Liberty drained her glass and leaned back in her chair to watch a pair of pigeons fussing and fluffing their feathers on the wall at the bottom of the garden. Without warning, tears began to trickle down her face. Her mother’s greatest gift had been her capacity to find happiness. Liberty hadn’t the first idea where to look.

Chapter 4

Geoffrey Court glanced down at the paperwork on the desk in front of him and straightened it unnecessarily. He pulled off his glasses, smiled at Liberty and then parked them back on his nose. A more diligent observer might have deduced his discomfort, but Liberty considered this visit to her mother’s solicitor to hear the terms of her last will and testament to be a mere formality. She was an only child and next of kin, so naturally she assumed that everything would come to her. Mr Court loosened his tie a fraction and cleared his throat.

‘As you are no doubt aware, Miss Bell, I drew up your mother’s will at her request and undertook to share its contents with you when the time came. Sadly, that time has now come.’

Liberty nodded encouragingly, hoping that it might speed things along. After a moment’s pause, the solicitor finally took the plunge.

‘I’m afraid it may not be the news that you were hoping for. Well, not hoping,’ he hurriedly corrected himself, ‘but expecting – perhaps that’s a better word.’

Now he had Liberty’s full attention.

‘Your mother’s last wishes were somewhat unusual. Perhaps the easiest way to begin is if you take a look at her will for yourself.’

Liberty felt a prickle of unease as he passed the relevant document across the desk. Mr Court watched her face crumple into a perplexed frown as she began to read. She understood the meaning of each word in isolation, but together they mutated into unnerving nonsense. This couldn’t be right.

‘I’m sorry, Mr Court, there must be some mistake.’

‘I’m afraid not, Miss Bell. Your mother was very clear in her intentions.’

‘But according to this, she left me nothing. Absolutely nothing at all.’

Mr Court pulled off his glasses once more and set them down on the desk. ‘Well, that’s not strictly the case. You may take whatever you wish from the contents of the house and its garden before they are sold.’

Liberty couldn’t believe what she was hearing. Her mother had left her without a penny, and soon-to-be homeless. It was completely unfathomable. And cruel. What on earth could she have done to deserve it?

‘She couldn’t have been in her right mind,’ Liberty protested, somewhat desperately.

Mr Court sighed. ‘I think we both know that she was,’ he replied gently.

‘Well, who gets it then – the money, the house, the antiques?’

Liberty’s disbelief was distilling into anger as the implications of her mother’s will began to sink in.

‘I’m afraid I’m not at liberty to disclose that. Your mother made me the sole executor of her will and she instructed me to keep the details of the beneficiaries confidential.’

Liberty leaned back in her chair and took a deep breath. She felt sick.

‘Would you like a glass of water?’ Mr Court enquired.

Liberty shook her head. A neat gin might be more helpful.

‘I realise that this might have come as a bit of a shock, but if you turn over to the second page you will see that your mother did, in fact, make some provision for you in her will.’

Liberty looked up at him, her expression full of suspicion, and then down again at the page he had directed her to. She read the words but was none the wiser for doing so.

‘What on earth does that mean?’

Mr Court cleared his throat again. ‘Mrs Bell left something in trust for you, but at present, I’m unable to divulge any specifics.’

Liberty was sorely tempted to reach across the desk and throttle him with her bare hands to squeeze some answers out of him.

‘At present!’ she exploded. ‘Well, if not now, then when? When the sodding hell will you be able to tell me what the buggering hell is going on?!’

It was unlike Liberty to swear – particularly in public – but these were unprecedented times. Mr Court raised his eyebrows in response to her expletives.

‘The inheritance from your mother is dependent on you fulfilling certain conditions. I am not able to tell you what they are, but I am to judge on your mother’s behalf whether or not her criteria have been met.’

Liberty felt like screaming. At first, she had been shocked, but now she was beginning to recognise her mother’s idiosyncratic stamp on these maddening machinations.

‘So let me get this straight. My mother has left me something, conditional on something else, and you can’t tell me what either of these somethings are?’

Mr Court nodded. ‘That’s exactly right. I’m also instructed to give you this,’ he added, handing her a carrier bag from behind his desk. Liberty snatched the bag from him and got up to leave. She’d had enough. But then something struck her.

‘How will you know when the conditions have been met?’

Mr Court stood up to see her out.

‘You are to meet me for lunch at regular intervals and I will … assess the situation.’

Liberty shook her head in disbelief. ‘Well, I hope you’re paying!’

Back home, she flung the carrier bag onto the kitchen table, sloshed some gin into a tumbler and took a bottle of tonic water from the fridge. When she looked inside the bag she found a small photo album and the latest copy of The Lady.

Chapter 5

The interviews for the granny nanny were being held in Venetia’s sitting room, which made Heron’s suggestion that Venetia should ‘leave it all to him’ and take no part in the final selection process herself all the more preposterous.

‘Of course I’m going to be there,’ she had told him. ‘I’m the one they’re supposed to be “assisting” and it’s my home they’ll be living in while you’re swanning around in the South of France.’ She would also be paying their wages, she thought ruefully. The successful candidate, should they manage to find one, would actually be living in the garden, in the studio flat above the former coach house that now served as a garage. Some years ago, Heron had persuaded his father to consent to the flat conversion on the grounds that it would make a profitable Airbnb, but once the work had been completed, Hawk had demurred, preferring instead to seek a ‘respectable, long-term tenant’. But he had never got round to it. Instead, it had been used occasionally as guest accommodation at Christmas when Hawk’s relatives had come to stay.

Heron and Venetia had eventually managed to whittle down a motley assortment of applicants to a shortlist of three. The CVs had made interesting reading. Venetia had immediately discounted the ex-headteacher of a girls’ school – ‘She can’t possibly need the money. She just wants someone else to boss about now that she’s retired’ – and a Nordic walking enthusiast – ‘She’ll be forever trying to get me to walk with those silly sticks!’ Heron had vetoed an army veteran aged sixty-three, who described himself as having ‘excellent organisational and interpersonal skills, a cheerful disposition and all my own teeth’. Heron declared that facile humour had no place on a professional job application and that, in all probability, the man was a gold-digger. Venetia was a little disappointed. She thought that he sounded quite fun.

The first interviewee was a Ms Stella Stoney. She arrived promptly and Heron met her at the front door and showed her through to the sitting room. She was dressed in a no-nonsense navy pleated skirt and matching cardigan over a white blouse and flat Mary Jane shoes with Velcro straps. Her grey-streaked beige hair was pulled back into a donut-shaped bun. Venetia’s heart sank.

‘This is my mother, Venetia Hamilton Hargreaves.’

Ms Stoney looked Venetia up and down appraisingly and offered her a hand to shake.

‘Good morning, Mrs Hamilton Hargreaves – or may I call you Venetia? I’m sure we shall get along famously.’

I’ll be the judge of that, thought Venetia.

‘Please take a seat, Ms Stoney – or may I call you Stella?’ Heron permitted himself a wry smile – which was quickly wiped from his face by her reply as she sat down with her legs spread and placed her hands firmly on her knees.

‘I’d prefer to keep things on a professional basis if you don’t mind, so I think we’ll stick with Ms Stoney.’

Heron sat down beside his mother and consulted his clipboard.

‘Right then, Ms Stoney, perhaps you’d like to tell us why you think you’d be suitable for the job?’

Ms Stoney flashed a confident, perilously-close-to-smug smile.

‘Well, I have over thirty years of nursing experience – eleven of those on geriatric wards and four in a nursing home for the elderly.’

Venetia flinched – that damn word again!

‘So you can be sure that any medical needs your mother has would be taken care of. Other than that, I’m punctual, well organised and have excellent interpersonal skills.’

Venetia begged to differ. The wretched woman was completely ignoring her and addressing all her answers to Heron, who appeared to be favourably impressed. He consulted his notes again.

‘And it says here that you have a clean driving licence and are au fait with online shopping.’

‘Absolutely. I’ve never had so much as a parking ticket, I have an Amazon Prime account and I’m a long-term Ocado customer.’

‘And you’re a competent cook?’

‘Oh, more than competent. I’m a great believer in good, plain wholesome food cooked from scratch. Much better for an elderly digestive system than too much rich food and alcohol. Although I wouldn’t want you to think I’m a killjoy – there’s no harm in the occasional glass of wine on special occasions.’

Venetia had had enough. She’d sooner run naked down the high street during rush hour than have this woman set foot in her house again. But she couldn’t resist making a little mischief before ending the interview.

‘Ms Stoney, what’s your favourite musical?’

Ms Stoney looked surprised, as though she had forgotten that Venetia was in the room. She glanced at Heron as though expecting him to intervene, but when he didn’t, she turned her attention back to Venetia.

‘Well, I’m not sure how relevant that is,’ she replied slowly and softly, as though speaking to a small child. ‘I’d have to give it some thought.’

‘It’s relevant because my son is keen to find me a companion to accompany me on outings – I believe it said as much in the advertisement – and I love musical theatre. I’m also a fan of opera – what about you?’

Ms Stoney looked relieved. ‘Oh yes – Oprah! Oprah Winfrey. Well, she’s certainly an interesting woman.’

Venetia smiled sweetly. ‘No, no – I’m afraid you’ve misunderstood. O-pe-ra,’ she continued slowly, adopting Ms Stoney’s earlier tone. ‘Puccini’s La Bohème and Bizet’s Carmen – that sort of thing.’

Ms Stoney refused to be ruffled. ‘I can’t pretend to be an expert, but I’m sure I’ll get the hang of it.’

Heron made a note on his clipboard. ‘Now, Ms Stoney, are there any questions you would like to ask?’

Ms Stoney shook her head. ‘I don’t have any questions, but there are a few things I should like to clarify. Firstly, I will need to see my accommodation.’

‘Of course.’

‘I should also point out that I don’t do cleaning, I don’t do personal care – assistance with washing, toileting etc. – and I don’t do dog-walking.’

‘My mother doesn’t have a dog,’ Heron replied, clearly keen to get away from the topic of toileting.

‘But I’m thinking of getting one now,’ Venetia added. She didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. The interview had been a farce as far as she was concerned. She would never consent to having Ms Stoney under her roof. But it had also been a stark and distressing reminder of her own mortality. A warning that she had passed the halfway point long ago, and was now facing, if not the final furlong, then certainly the closing stages of the race, with all the frailties and indignities that it might entail. And it did seem now as though her life had raced away from her like a runaway horse. Was this truly all that was left to look forward to – infirmity, insanity and incontinence? While Heron showed Ms Stoney the studio flat, Venetia went through to the kitchen to fix herself a medicinal gin and tonic. As she went to the fridge for ice, she caught sight of a note that Kite had given her a few days after he had taken the chess set home.

‘You’re the best, Nisha! Love you lots from your wingman Kite xxx’

The thought of her grandson banished her gloom. What had she been thinking? Old age might be coming for her, but she wasn’t going down without a fight. Kite needed her as his protector and potential chess partner, and now that Hawk was gone, she could have a whole new life if she wanted. And she did want. She took a large swig from her glass and checked her watch. Heron would be mortified if he caught her drinking before 6 p.m. on a weekday. There were twenty minutes before the next candidate arrived and this time, Venetia was going to take charge of the interview. She watched as Heron accompanied Ms Stoney back through the garden and down the side of the house out to the street, where her car was parked.

Good riddance! she thought.