11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

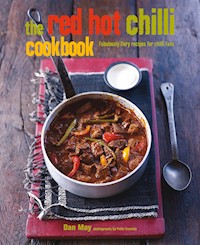

Trees Can't Dance began over 4 years ago at the world's most northerly chilli farm. Against all conventional horticultural wisdom Dan May began growing chillies in the wilds of Northumberland. It wasn't long before Dan had to find something to do with all the produce. Disappointed with the quality of the chilli sauce brands available in the UK, he hit on the idea of filling a gap in the market by producing his own sauces using home-grown ingredients. In this fabulous book, chilli guru Dan shares more than 70 recipes celebrating chillies in all their varieties and strengths. Acquaint yourself with the history of chillies, how to grow them at home and how to identify the key varieties. There are ideas here for every kind of dish: soups and salads; nibbles and sharing plates; mains; side dishes; sauces, salsas and marinades; sweet things and drinks. Mouthwatering recipes include Thai Beef Noodle Soup; Moroccan Spiced Lamb Burgers; Texas Marinated Steak with Stuffed Mushrooms; Sweet Chilli-glazed Ham; Quick Chilli Lime Mayonnaise; three fiery pasta sauces; Chilli Pecan Brownies; and Chilli Hot Chocolate. Dan May once worked as a landscape photographer and he started grow chillies in 2005. Before he knew it, he had the world's most northerly chilli farm. Trees Can't Dance now supplies a range of chilli sauces throughout the UK, Europe, the Middle East and beyond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Design and Photographic Art Direction Steve Painter

Commissioning Editor Céline Hughes

Production Manager Gordana Simakovic

Art Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Food Stylist Lizzie Harris

Indexer Penelope Kent

First published in 2012 by Ryland Peters & Small 20–21 Jockey’s Fields London WC1R 4BW and 519 Broadway, 5th Floor New York, NY 10012 www.rylandpeters.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All photography by Peter Cassidy except pages 7, 9, 11–13 and 15 by Dan May.

Text © Dan May 2012Design and photographs © Ryland Peters & Small 2012

Printed in China

The author’s moral rights have been asserted.All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

UK eISBN: 978-1-84975-325-8

UK ISBN: 978 1 84975 222 0

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Notes

• The recipes in this book are given in both metric and imperial measurements. However, the spellings are primarily British and this includes all terminology relating to chilli peppers. British ‘chilli’ and ‘chillies’ are used where Americans would use ‘chile’, ‘chili’ and ‘chiles’.

• All spoon measurements are level, unless otherwise specified.

• All chillies are fresh unless otherwise stated.

• All eggs are medium (UK) or large (US), unless otherwise specified. Uncooked or partially cooked eggs should not be served to the very young, the very old, those with compromised immune systems, or to pregnant women.

• When a recipe calls for the grated zest of citrus fruit, buy unwaxed fruit and wash well before use. If you can only find treated fruit, scrub well in warm soapy water and rinse before using.

• Ovens should be preheated to the specified temperature. Recipes in this book were tested using a regular oven. If using a fan/convection oven, follow the manufacturer’s instructions for adjusting temperatures.

• Sterilize preserving jars before use. Wash them in hot, soapy water and rinse in boiling water. Place in a large saucepan and then cover with hot water. With the lid on, bring the water to the boil and continue boiling for 15 minutes. Turn off the heat, then leave the jars in the hot water until just before they are to be filled. Invert the jars onto clean kitchen paper to dry. Sterilize the lids for 5 minutes, by boiling, or according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Jars should be filled and sealed while they are still hot.

contents

introduction

soups & salads

nibbles & sharing plates

main dishes

side dishes

sauces, salsas & marinades

sweet things & drinks

suppliers & stockists

index

Why Trees Can’t Dance and Chillies Rock

It’s amazing what you can achieve when you live too far from anyone to hear them telling you that it won’t work.

In the spring of 2005, I began growing chillies on a beautiful if unlikely site clinging to the very edge of the North Pennines in northern England. Sixty types of chilli from every corner of the world were planted with a happy optimism that seemed to fly in the face of conventional horticultural wisdom. At 600 feet above sea level, the project was seen as a challenge. Despite many, many mistakes, by the late summer we had our first, staggeringly large, crop of chillies.

They may have come from the tropics of the world but they seemed happier to be here than we had ever imagined, and I soon found myself running the world’s most northerly chilli farm. I had never intended to become a farmer or even a horticulturalist but, despite myself, by this time I suppose I had. My simple intention was to plant and grow chillies to get top-quality, fresh ingredients to make some of the dishes I had enjoyed on my travels. The reality was slightly different; I had polytunnels full of plants that needed constant attention and come the summer, I had mountains of fresh chillies and no sensible idea of what to do with most of them. I already had a full-time business to run as a landscape photographer and I really didn’t need another one.

However, you can never escape your upbringing and I could just hear my dad saying, ‘if something is worth doing at all, it is worth doing properly’, so with a great deal of help, a disused stable was converted into a small commercial kitchen and we began the exhaustive process of taking the traditional chilli recipes I had gathered and turning them into what we hoped would become the world’s best culinary chilli sauces! We began selling at farmers’ markets and, as our confidence grew, through delis and farm stores, eventually taking them to national trade shows and developing a network of outlets selling our range throughout the UK and Europe.

Six years on and every day is still devoted to meeting our own ludicrously high standards for the chilli sauces, marinades and ever-growing list of chilli condiments we produce. All our sauces are still lovingly made by hand to our (daftly) exacting specifications. We are lucky to have considerably more comfortable premises (although still a little chilly in the winter) and a small and devoted team who are tireless in their pursuit of chilli excellence. We now supply everyone from independent stores and local delis through to major multiple retailers both in the UK and abroad. But none of this has ever compromised our own belief that quality matters; each recipe is the product of many hours of hard labour over a hot stove with the finest natural ingredients, and we know that you (and your taste buds) appreciate that!

We often get asked why we call ourselves Trees Can’t Dance. Trees have an interesting place in folklore throughout the world. The idea of a dreaming tree, somewhere of permanence to go and sit, think and solve your problems is a common theme not only in Celtic tradition but also in the cultures of Native American Indians, from which most modern chilli plants originated.

You may not be able to solve all your problems by thinking about them, but combine it with dancing and who knows?

The History and Spread of Chillies around the World

Chilli peppers are thought to have originated in the northern Amazon basin and so, by natural geographic spread, are indigenous throughout Central America, South America, the West Indies and the most southerly states of the USA.

The Tepin or Chiltepin pepper (Capsicum annuum var. glabriusculum) is reputed to be the oldest variety in the world and is commonly called the ‘Mother chilli’. It grows wild in northern Mexico and up into Arizona and Texas where it is now the State chilli. It is particularly hard to domesticate but in the wild it grows best in seemingly impossibly harsh habitats. In areas of extremely low rainfall, such as the Sonoran desert, it can be found thriving in the partial shade provided by a Desert Oak or Mesquite. In these conditions this supposedly annual plant has been known not only to survive but also to fruit for up to 20 years. This is an interesting feature of most chillies; if they are in conditions they like, they will not only thrive for several years, they will also be more prolific fruiters in their second, third and fourth years.

The Tepin is truly a wild pepper and it is further south in Peru and Bolivia where we find possibly the earliest domestication of a variety of chilli, Rocoto or Locoto, some 5,000–6,000 years ago. Evidence has also been found for chilli cultivation in Ecuador from around the same period. Later, the Aztecs were famous for their love of chilli and it featured heavily in their diet. The favourite drink of the Aztec emperors was a combination of chilli and chocolate. Such is their connection with these peppers that the word ‘chilli’ is derived directly from an Aztec or Nahuatl word; as is ‘chocolate’ for that matter!

The Portuguese traders of the sixteenth century were behind the spread of chillies around the world. At the time, the Portuguese empire, the first truly global empire, traded with and often colonized areas as widespread as South America, East and West Africa, China, India and Japan. In 1500, the explorer Cabral landed (probably by accident) in Brazil and over the next 200 years, chillies spread quite swiftly through the Empire, eventually becoming indigenous to the cuisine of all the Portuguese colonies.

Although as early as the sixteenth century the monks of Spain and Portugal experimented widely with chillies in cooking, quite strangely the use of chilli peppers did not spread widely across Europe from Portugal but rather back from India along the spice routes through central Asia and Turkey. The British colonization of India marks the beginning of the spread of chilli and in particular curry spices into British cuisine. Initially this was in the form of fish molee and lamb curry, staple dishes of the Raj.

Today, an astonishing 7 million tonnes of chillies are grown every year worldwide. Although Mexico still grows the widest variety, India is the largest producer, growing approximately 1.1 million tonnes and supplying nearly 25% of the world export market for red chillies. China is the second largest producer and is likely to overtake India in the next few years.

Folklore and Unusual Uses

Throughout the world and all through history, chillies have been put to various exotic and unusual uses – from deterring vampires and werewolves in Eastern Europe, to deterring marauding wild elephants in modern-day Assam. They are used in a significant proportion of the most celebrated hangover cures worldwide and can even be an active ingredient in make up – as blusher, giving cheeks a healthy glow. Chilli eye drops have been used as a cure for headaches and chilli powder has even been rubbed on the thumbs and fingernails of children to prevent them sucking their thumbs and biting their nails.

Health and Dietary Benefits

Chillies are cholesterol free, low sodium, low calorie, rich in vitamins A and C, and a good source of folic acid, potassium and vitamin E. They have a long history as a traditional remedy for, amongst others, anorexia and vertigo. They have more scientifically recognized application in the treatment of asthma, arthritis, blood clots, cluster headaches, postherpetic neuralgia (shingles) and burns.

By weight, green chillies contain about twice the amount of vitamin C found in citrus fruits. Red chillies contain more vitamin A than carrots. To put this into context, eating 100 g/3½ oz. fresh green chilli can give up to 240% of an adult’s recommended daily allowance of vitamin C.

As I’ve mentioned, chillies are very low in sodium, containing 3.5–5.7 mg per 100 g/3½ oz., but they are big on flavour. So, adding chilli spice to meals adds seasoning and pungency, counteracting the need for salt and bringing the sodium level down even more. Moreover, chillies contain about 37 calories per 100 g/3½ oz., depending on the variety. Eating meals with approximately 3 g chilli causes the body to burn on average 45 more calories than an equivalent meal that does not contain the additional chilli. After eating, our metabolic rate increases – this is the ‘diet-induced thermic effect’ – but chillies can boost this effect by up to a factor of 25. So eating meals with chilli can reduce the effective calorific content!

Identifying Chillies

All chillies belong to the Capsicum family, of which there are 5 different species. As most specific varieties have spread around the world, they have been given common names in each geographical area and even naturally crossbred with locally indigenous species. This can make them extremely tricky to identify – taste is perhaps the most effective method, closely followed by our incredibly insightful sense of smell. Each species has common varieties with which it is easy to become familiar while you are perfecting your own individual olfactory and organoleptic identification technique!

Capsicum Annuum, meaning annual, is the most common. This, however, is misleading in itself as all pepper plants, given favourable conditions, are perennial. The Annuum species contains most of the more common varieties of chillies, including the Jalapeños, Cayennes, Poblano, Serrano, regular sweet/bell peppers and the ‘mother’ of all chillies, the infamous Chiltepin.

Capsicum Frutescens tends to have a quite limited variety of pod shapes but still contains some the best-known chilli varieties. The Tabasco chilli made famous in McIlhenny’s ubiquitous hot sauce is part of this species, as is the Bird’s Eye chilli and most of the common Thai chillies. It also contains perhaps the best-named chilli around – the Malawian Kambuzi.

Capsicum Chinense, or Chinese Capsicum, contains most of the hottest varieties of chillies: Habanero, Scotch Bonnet, Datil and even the super-hot Naga varieties, although it has recently been shown that some of the hottest Nagas in fact share genetic material with the Capsicum Frutescens species. These varieties have a very distinctive, fruity aroma and impart that characteristic to any dish prepared with them.

Capsicum Pubescens is a species characterized, as the name suggests, by coming from plants with hairy leaves and stems. They are mostly found in South America and can have significant hardy qualities that allow them to grow at some altitude in Chile and Peru. The most common chilli pepper from this species is the Rocoto or Manzano.

Capsicum Baccatum is another widespread species throughout South America and includes many of the Aji family of chilli peppers prevalent in South American cooking. These varieties are not very common outside their native countries but you occasionally see them grown commercially in southern areas of the USA, where they are frequently referred to as chilenos. The Baccatum plants tend to grow quite tall and tree-like. The peppers themselves are often described as fruity or even citrusy in flavour.

Dan’s Simple Guide to Growing Chillies

If you can grow chillies in the wilds of Northumberland, then you can grow them just about anywhere. Like many non-indigenous plants we now enjoy growing in unusual locations, they need a little extra care and protection, particularly in the winter time when temperatures and light levels can be both inconsistent and, to be honest, a little disappointing.

I have fond memories of planting my first trays of chilli seeds in a triple-insulated and heated greenhouse with the wind howling outside and snow piling up on the roof. It was the end of December in northern England and I still remember the thrill of seeing the first shoots appearing through the soil – and the sheer dread of receiving the utilities bill for the cost of heating the greenhouse through the chilliest winter I can remember. You, however, don’t need to go this far; if you have a warm windowsill, you can give your plants a great start in life!

You can plant your chilli seeds anytime between end of winter and end of spring, but by planting them early you give the chillies time to ripen in the warm summer months and some will even be ready in time to spice up your summer barbecues. It is worth noting that the hottest (and more unusual) varieties of chilli tend to have the longest growing season as they are used to life in the tropics where temperatures are consistent all year round.

First, fill a multicell seed tray with multipurpose compost, firm down and moisten with water. Place a seed in each cell and lightly cover with compost and water again using a very fine spray so as not to disturb or compress the soil too much. I often cover my freshly sown seeds in a thin layer of vermiculite rather than compost – this has a more open structure and makes it easier for the fragile first shoots of growth to push up into the light. It also acts as a layer of insulation, helping the compost to retain warmth.

If you live in a relatively cool climate, it won’t be possible to start growing the chillies outside. In this case, if your seed tray did not come with a clear lid then improvise by placing clingfilm/plastic wrap over the tray to create a greenhouse effect and place in an airing cupboard or anywhere similarly warm to germinate. Chilli seeds like temperatures of around 25°C/77°F to encourage relatively swift germination. At too low a temperature, germination can become sporadic and take far longer than expected.

Check your seeds daily for signs of life and keep the compost moist. Be careful not to overwater them; the compost should be slightly damp to the touch but not sodden or too wet.

As soon as seedlings appear (this can take 2–4 weeks), they need sunlight, so put them somewhere warm with plenty of daylight – a windowsill above a radiator is ideal. Keep the compost moist; at this point it is ideal to water from below by placing the multicell tray in a secondary seed tray lined with capillary matting, which is also easier to keep damp. The moisture will be drawn up into the compost and will in turn encourage the plants to put down strong roots to reach the moisture. Feel the surface of the compost daily to check that it is sufficiently moist. Remember that young seedlings are very fragile and can be scorched if left in direct sunlight, particularly as the heat from the sun increases in the springtime.

When the seedlings sprout a second set of leaves (their first true leaves), transplant them to their own pots – a 7-cm/3-inch diameter pot is good. Pop out your seedlings from the tray, being careful not to damage the roots. Fill the pot with compost, moisten with a little water and dig a well for the seedling. Drop it in and gently firm the compost around it.

You can boost your crop by feeding your plants once a week with diluted liquid tomato fertilizer.

Once your plants reach between 12 and 15 cm/ 5 and 6 inches, it’s time to move them to a bigger pot. A 12-cm/5-inch diameter will be big enough for one plant or you can fit 3 in a 30-cm/12-inch pot. Fill the pot with compost to about 1 cm/½ inch from the top. Don’t worry if you cover up some of the stem, as the plants will sprout new roots from the buried area.

By the time your plants are about 20 cm/8 inches tall, it’s a good idea to give them some support by gently tying them to a bit of cane with some twine. As they grow, this can also be used to tie supports for the fruit-laden branches, as they can become too heavy to support themselves.

When they reach 30 cm/12 inches, pinch out the growing tips to encourage outward ‘bushy’ growth. This is ideally done just above the fifth set of leaves.

By end of spring (depending on where you are in the country), it’s warm enough to put your plants outside. Make sure they are in a sheltered area but where they’ll receive plenty of sunlight – ideally against a wall facing the sun so that the latent heat built up in the wall will keep them warmer if nighttime temperatures drop a little low. If you’re growing tropical varieties, ie Habaneros, or live somewhere particularly cold, it is far better to grow them in a greenhouse if you have one, or even on a warm windowsill.

At this stage, it might be an idea to move your plants to a bigger, sturdier pot; a 20-cm/8-inch diameter is big enough for each plant. Keep a daily eye on your plants for signs of aphids; chilli plants, like tomatoes, are a favourite of greenfly and whitefly. If you do find a few on your plant, remove them by hand or with an application of soft soap solution.

Continue feeding your plant with the fertilizer dilution (as you would a tomato plant), as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Also be sure to check that the compost is moist. By now the plant should be flowering; it’s these flowers which, when pollinated by insects and bees, will develop into chillies. You can help the plants out by doing some hand pollination! This means dabbing a cotton bud into each flower in turn thus mimicking the way a bee may move the pollen from flower to flower. Doing this will greatly increase your fruit yield!

You should be able to harvest some of your chillies six months after you first sowed the seeds, however varieties such as the Habanero take longer to develop. It’s a good idea to harvest the first green chillies early, as chilli plants will fruit a few times across the season (spring to autumn) and harvesting will encourage a bigger second growth. Simply snip the chilli pods at the stalk. Once you’ve done this, you can let the next fruit mature to red for a more rounded flavour.

Although we view chillies as annual plants in the UK, their fruit yields will increase in the second and third years if you can successfully ‘over-winter’ them. To do this, at the end of the growing season, choose a healthy plant and cleanly cut it back to leave the stem and a few strong healthy branches. Make sure that the plant is free from pests and that the compost is quite fresh. Place the plant on a warm windowsill, trying to avoid cold drafts, and give an occasional modest feed of diluted liquid tomato fertilizer to help boost the plant’s ‘immune system’. A successfully over-wintered plant will begin to produce growth and in turn, fruit earlier and more prolifically than a plant grown from seed that year. Eventually, after about four to five years, yields begin to fall and it’s time to retire that plant!

Now all that’s left is to transform your chillies into delicious dinners, sauces, marinades and preserves.

Where Does the Heat Come from?

The heat in chillies comes predominantly from a natural alkaloid chemical compound called capsaicin. When we eat a chilli, the presence of this compound will immediately be sensed by the pain receptors located in your mouth and nose, and eventually your stomach. These cells send a message to the brain to release endorphins into the body. The rush of these natural painkillers often produces a feeling of great wellbeing and it is this sensation that frequent consumers of hot chillies can become addicted to. Like all addictions though, in order to maintain the intensity of this reaction, it becomes necessary to consistently increase the dose! In 2006, it was discovered that tarantula venom activates the same pathway of pain as capsaicin. Not only is this the first demonstration of a shared pathway in both plant and animal ‘anti-mammal’ defence, but it also gives a clear indication of how potent capsaicin can be.

If you have ever been tempted to take a bite of even a fairly mild chilli, you will know the burning sensation that capsaicin produces – and we have all seen how competitive eating chillies can get! So what are the remedies if the burning gets too much?

Firstly, the things to avoid are water or water-based drinks – this includes beer. In many cases they will actually make the sensation more intense. Capsaicin is not soluble in water and although alcohol is a solvent to capsaicin, it is not a neutralizer, so it is likely that relief will only be temporary and may well carry the burn to other areas of the mouth and throat. It is widely accepted that the most effective remedy is to take a small mouthful of vegetable oil and swill this around your mouth. Due to the hydrophobic composition of capsaicin (like that of oil), it will form a solution with the oil. Spit the oil out and it will take a significant amount of the ‘heat’ with it. Other effective remedies are drinking cold milk, yogurt or a cool sugar syrup solution. These methods work equally well if you find yourself with a bad case of Hunan hand, which occurs when skin burns due to overexposure to chillies. Although not common in the UK, overexposure to chilli peppers is one of the most common plant-related symptoms presented at hospital emergency and poison centres throughout regions where peppers are grown and processed on a large scale.

The heat in chillies is thought to be their natural defence against mammals who, when eating them, would crush their seeds with their molars; thus preventing the plants reseeding. This is further supported by the fact that birds, who pass the seeds directly through their digestive systems, are unaffected by the capsaicin that gives chillies their heat; thus allowing the plants, via birds, to spread their coverage more widely than relying on the natural distribution of the wind and the mammals who happened to swallow the fruit whole.

Contrary to popular belief, the seeds of the fruit are not the source of the chilli’s heat. The hottest part of the chilli is in fact the placenta that holds the seeds to the internal walls of the fruit. Its heat is in turn due to its direct contact with the tiny glands that actually produce the capsaicin within the wall of the chilli. It is also worth noting that the precise make up of the different capsaicinoids within various chilli varieties can actually deliver the sensation of ‘heat’ in different ways for different people.

This illustrates one of the key problems facing Wilbur Lincoln Scoville when in 1912 he created his now legendary ‘Scoville Organoleptic Test’. This was the first attempt to devise an accurate way of gauging the hotness of chilli peppers. A panel of (usually) five volunteers tasted extracts from specific chillies added in exact quantities to a sugar and water solution. The first point at which the chilli heat was undetectable gave the Scoville rating for that chilli. For example, if a Naga Jolokia was rated at 1,000,000 Scovilles, its extract would need to be diluted over 1,000,000 times before the heat became undetectable to the taster. It relied greatly for its consistency on the taste buds of the volunteers. Thus, although it provided interesting comparisons between varieties of chillies, it was too subjective for reliable results.

Currently, ‘heat’ is measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). In its simplest form, this separates the capsaicinoids from all other liquids present in the chilli. This allows the concentration of heat-giving compounds to be calculated in parts per million. The unit of measurement in this case is not the Scoville, but the American Spice Trade Association pungency unit, or ASTA for short. Despite the consistency of test results within any particular lab using this method, it is interesting to note that results produced by different labs relating to a single variety of chilli can show wide variances in the final heat levels recorded. This illustrates the difficulties in accurately assessing the heat of an overall chilli cultivar rather than a single pod. At its most basic, heat levels in a single species of chilli can vary by anything up to a factor of 10; so you may get a very hot one or a not so hot one. The heat can also be heavily influenced by external factors, such as soil, temperature, humidity and feed regime, as well as the genetic make up of the original plant from which the seed was gathered.

To get from the ASTA unit to the approximate Scoville rating for a chilli we need to multiply by 15; however, as has been illustrated, the results should be seen as indications of heat rather than fact.

It is generally accepted that pure capsaicin has a Scoville rating of around 16,000,000. However this is not the hottest alkaloid found in the natural world. Resiniferatoxin that exists in the sap of some Euphorbias (which grow wild in Morocco) is 1,000 times hotter that pure capsaicin, giving it a Scoville rating of 16,000,000,000!