Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

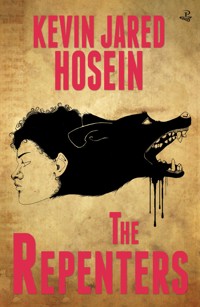

When the infant Jordan Sant is taken to the St Asteria Home for Children after the murder of his parents, he sets out on a journey that is a constant struggle between his best and worst selves. One relationship, with the young nun the children call Mouse, awakens the possibilities of love and hope, but when Mouse abandons her calling and leaves the home, the world thereafter becomes a darker place. When, barely a teenager, he runs away from the home to scuffle for a living in the frightening underbelly of Port of Spain, Jordan reaches the lower depths of both Trinidadian society and himself. In Jordan Sant, Kevin Jared Hussein creates a narrator who gets under your skin. He takes us into the most dreadful places of human experience, confesses doing seemingly unforgivable things. But though Jordan knows how inescapable circumstance can be, he never denies responsibility for his actions. But can this Dostoyevskian figure save himself? The Repenters takes us to places in Trinidad readers will have never been before. In Kevin Hosein the Caribbean announces a writer whose work is poetic, Gothic, and deeply transgressive, whose creation of a voice for Jordan Sant is troubling, engrossing and not to be forgotten.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are saints among us, found in the deepest fractures, serving without promise of award or apotheosis. Not willing to risk omitting any names, I would simply like to thank these selfless counsellors and educators – and all those who live to foster the futures of broken childhoods.

To get into the specifics now, I’d like to acknowledge my mother and father, Merle and Ashraff, who have supported me since my pre-teens through this mostly tricky and thankless undertaking of mine; Shivanee Ramlochan, my editor and friend, who has probably vivisected three iterations of this manuscript; Jeremy Poynting and Jacob Ross, both a pleasure to work with and both instrumental to the final draft, as well as the rest of the folks at Peepal Tree Press for giving this book a shot; and finally, Portia, who is there for me whenever I hit a dead end, or any of the various other occupational hazards that come with this literary calling.

KEVIN JARED HOSEIN

THE REPENTERS

First published in Great Britain in 2016

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2016 Kevin Jared Hosein

ISBN13 (Epub): 9781845233402

ISBN13 (Mobi): 9781845233419

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission

‘Those are the orders,’ replied the lamplighter.

‘I do not understand,’ said the little prince.

‘There is nothing to understand,’ said the lamplighter.

‘Orders are orders. Good morning.’

And he put out his lamp.

— The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

CONTENTS

I. The Saints

1. ‘This is a long road that has no turning.’

2. ‘Time runnin out. So we just havin we fun.’

3. ‘It’s just going to add smoke to their minds.’

4. ‘Because I am a scorpion, you foolish frog.’

5. ‘Why?’

6. ‘People only remember you at your worst.’

7. ‘I will come and fuck them up!’

8. ‘Easy way to kill somebody who already killin theyself.’

II: The Sinners

9. ‘Place like this – the house does always win.’

10. ‘All in the name of love.’

11. ‘Run, especially if it have nothin to run to!’

12. ‘Let God have somethin to thank me for.’

II. The Repenters

13. ‘It damn well felt illegal at the time, though.’

14. ‘We’ve become too dependent on God.’

15. ‘Can’t help but feel a lil jealous.’

16. ‘Somebody need to take care of that dog.’

17. ‘This is me being brave.’

18. ‘I need you to be fearless now.’

About the Author

Recent Contemporary Fiction From trinidad

I

THE SAINTS

-1-

‘This is a long road that has no turning.’

*

The people put me in St. Asteria after my mother and father was murdered. Nobody was ever too sure what really went down. All they know is that on that day, old Mrs. Boodram overhear some commotion from the house next door – glass breakin, cupboards rattlin, woman screamin out for the God Almighty, the works. After the old woman ring up the house and get no answer, she push poor Mr. Boodram to go over and check out the scene.

The old man, after trampling a path through the overturned kitchen, nearly shit his pants as he cross into the ransacked living room. Armoire lying face down, shards of pots strewn cross the floor, where the light filterin in from the window shining right on a little boy wading in a shallow pool of gore. Splashed on the floor, as if hurl from a pail.

The body and the blood.

The statement and testimony.

I being honest when I say I can’t remember a damn thing.

I was only two. I ain’t know how people expect me to remember.

They tell me that I coulda be repressing memories bout the day – that if you open up my brain, you’ll find the sorrow swimmin in some knot of nerves in there. I joke round a couple times and say how the damn thing was probably my own doing. How it was probably me – my bloody-up two year old self – who mastermind the massacre. Nobody ever find that kinda joking round funny. I never bother to follow up on any of it. Never had no need to. The talks and therapy wasn’t worth jack shit either. It ain’t have no cut to heal if the knife never break the skin.

Have a saying: Time longer than twine.

Learn that and you can get through the day. In the end, it’s okay. Even if you die, it’s okay. It ain’t God’s business to save the bodies. People see the bright and the young go out in a muzzle-flash and get the wrong idea. Give God a chance with your soul and you will be okay. You have to open up and look at the grand scheme of things. All bad things come to an end, but not without casualties. God don’t owe you anythin beyond that point. The ones who survive are the people who God have His eye on. And I could tell you one surefire thing. Since the clock start tickin, since before I could remember, God has watched over me.

My parents’ names, they had tell me, was Ishmael and Myra Sant. Ishmael succumb to two cutlass wounds to the chest. Never seen it myself but I can’t help but picture a big bloody crucifix tattooed to the flesh. Myra collect a knife to the jugular. Think there was rape involve too. I’m only sayin that because when Sister Mother and Father Anton took me to the sanctuary that day to tell me bout the whole damn mess, I know they was holdin back, just from their tone. The story don’t seem messy enough. Some pieces was missin. For my own good. See, Father Anton ain’t have it in him to mention rape to a child. Careful what you put in your mind, he always say, cause it’s hard to get it back out.

The church always smell like wood shavings. There was always something heavy in there, a pressure slowly fillin the spaces. During choir and the Sunday sermons, I use to hear the bats squeakin between the roof and the rafters. I mention it once, and the others look at me like I was mad. Like I had bats in the belfry.

I was twelve then, give or take. Most of the others was round that age at the time.

Father Anton to my right and Sister Mother to my left. Father Anton had his hand sling over the back of the bench. Sister Mother sat upright as she always did, a squint-eyed gaze on the crucifix the whole time. I grab my knees and rock back and forth, my eyes focus on the glints of light shootin through the stained speckled window of Mother Mary, dappling the floor.

Father Anton mutter under his breath, ‘All of that just for a little bit of money.’

‘The wicked stop at nothing. Don’t underestimate them,’ Sister Mother say straight out. She turn and say, ‘Jordon, are you listening to me, boy?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ I reply, my voice quick and faint.

Hushed, but unapologetic, she say, ‘You owe your life to God. Forgetting a debt doesn’t mean it is paid. I’m here to remind you, boy, if you don’t honour what was done for you, and you end up lying with the dogs, you’re well on your way to rise with the fleas.’

Sister Mother was an old white woman, come to Trinidad from God-knows-where. She was the boss. She wasn’t Old Testament, but when she enter rooms, she coulda rasp the chatter right outta the air. We’d all snap to attention quick-quick. Her face was hard – skin stretching tight over bone at her sallow cheeks. Grey eyes like samurai steel, tipped with piercing righteous pupils. Her hair, if she had any, was always concealed by the wimple and veil. She was tall. A woman with height like that, you would picture to be hunchback, but she always make it her business to keep her back stiff and sit up straight. She make it our business too – all of her children at St. Asteria had to follow suit. Her children also included her superfluity of nuns – that’s the collective noun for nuns, yes, a superfluity. Learn that I did.

She never pretend to come from Trinidad, or the twentieth century. Never try to rinse her accent with patois or Creole. Sometimes she seem to go outta her way to be as otherworldly as possible. More than once, she declare that the only people who excel in this country is the ones who reject it, meanin the ones who coulda swim outta the black hole that is sweet, sweet T and T. After all, most people who excel here – in the ways that matter – make the move of clearing their throat of the acidic, sulphurous phlegm that is the Caribbean dialect.

Aye – her words, not mine.

During dinnertime, Sister Mother use to put on some old-timey folksy music on this ancient record player she had. The music was for her and her alone – you didn’t have to like it, but you could not challenge it. Doing that was like Oliver Twist asking Mr. Bumble for more gruel. Tell you, she was the boss. The songs was in English, but in one of them funny foreign accents. French. Or Scottish. Or German. Shit, I ain’t know. Never coulda tell the blasted difference. Not sure if the others did either. We was too busy trying to sit up straight and chew seven times before swallowin. We use to count it, because she use to be countin it too.

‘Sometimes I feel it is hopeless,’ Father Anton say, suckin on his gum. ‘I try to teach them to be good. But they’re still going out in a world that is not.’

She say to him, ‘We aren’t preparing them for this world, Father. We prepare them for the one after.’

Looking at me, she say, ‘Those men who killed your parents took away everything your family could have been in this life – they were evil. But they saw the Lord in you. The fear of God struck them and they couldn’t touch you.’

Father Anton was still mumblin, ‘Just for a lil bit of money. All this nonsense – ’

Sister Mother clear her throat. ‘You’re still alive. You’re still in control of your fate – you are the captain of your soul. Am I making myself clear? You didn’t choose to come here to St. Asteria. But you can choose where to go from here. Don’t be fooled. The mills of God grind slowly but they grind finely. This is a long road that has no turning…’

‘How you feeling, Jordon?’ Father Anton cut in. ‘You upset?’

I say, ‘No. Not upset, no.’ And I really wasn’t, but I don’t think I coulda ever convince the old man otherwise. Something in my tone maybe. The whole time I know him, he never seem like he age a day. The man drifted outside time. He was a mountain – tallest man I ever come across. You’d never see him without his cassock. Working for God was a full-time job, he say, and one must always wear the uniform on the job. His dark skin lost some considerable amount of its hue as the years went by, as if it was washed out by worry, as if his skin turn to shale. He had the whitest hair and beard, like chalkdust smeared on ashes. His glasses obscured his wall-eyed gaze and the bags under his eyes.

Father Anton held a picture of Ishmael and Myra between his thumb and forefinger. He flick it like it was a playing card. Was from a cutout of a newspaper. A photo with the caption, HAPPIER TIMES: Ishmael and Myra Sant on their wedding day. They pose side by side at the steps of a small rural church. He in his cheap tuxedo, she in her hand-me-down dress. He had short hair, and she had long pincurls. He had squinty eyes, and she had big eyes. He was tall, and she was small. He was Indian and she was African. Even though they was such opposites, they had the same broad smile.

They look like nice people. That was all I coulda say.

Father Anton thought something woulda turn on, some switch woulda click, some hundred-watt bulb woulda blaze a path through my dark memories. But nothing ever come. Not no spiritual shudder, not no tightenin of the asshole. The earth didn’t contract and squeeze a reaction outta me. My nose turn up a little, my mouth twistin slack as I shake my head at him. I just couldn’t look at the picture and feel what the old man wanted me to feel. For a second, it was as if I coulda see into my own mannequin stare. Like I was outside myself.

Father Anton lean in towards me, cradling his chin in his palm. ‘How come you asked about them?’

That was the deal for some of us at St. Asteria. If you wanted to know the disastrous shambles of the past, St. Asteria waited until you asked. It was a rite of passage, almost. But I didn’t care bout knowin. Rey did. So I tell them the truth.

Sister Mother furrow her brow. ‘You mean you didn’t want to know?’

‘I don’t really think bout it. I here now. That’s enough for me.’

She shake her head and Father Anton scratch his neck, both of them in disapproving silence. Then they both put their heads down. They each held my hand – Father Anton, my right and Sister Mother, my left. And the three of us pray to God. But my eyes stray up to the crucifix over the altar. Its slanted grimace. Its blank wooden eyes. I know the only people who say, ‘God is good’ is the ones who God is good to, or those wishing that God was good to them. At that time, reflecting on the images they put in my mind – the overturned room, the toddler in the blood, and the light shining over him – it was them three words that loop in my head: God is good.

When I went back to my room to tell Rey the details, he was quiet at first. And then he ask, ‘How you feel when they tell you?’

I just give him a shrug. ‘Normal.’

Rey was already shack up here at St. Asteria when I’d first come through these doors. And we live together in the same room since that. He was the shortest boy in St. Asteria. The big head and big glasses didn’t help the image either. He was always tryin to grow a ’fro, but Sister Mother use to strap him to the toilet and shave it off.

St. Asteria ain’t like the other homes – ain’t pack like them, anyway. Was just eight of us or so at the time. I remember when we had to lay mattresses on the floor. That was all we had till Sister Mother manage to scour a donation from the Government – election time is always good for things like that, and she was savvy enough to always take advantage of it. I remember the people put up an article in the papers and all when that grant come through. Best thing we buy was a bunk bed for each room, though the first fights we had with each other in St. Asteria was base round deciding who was gon get the top bunk. Rey and me just decide to switch top and bottom every other week. Never had no worries with Rey. Never had no fight, no beef, no squabble. Not at the time, anyway.

We was never too close, not like how you woulda expect children of misfortune to be. You’d think grief would be a bond between people, cause it’s all they know. Rey was in the same boat as me, too young to properly digest and absorb tragedy into the blood. I think we both use to think somethin was wrong with us because we couldn’t feel nothin. Possibly hit him harder than it hit me. I think we had more in common than he woulda ever let on, but he thought I was strange, and he didn’t want to be like that, so he disguised our similarities. He always feel the need to reassure everybody that he was just like them, even though nobody here was like anybody else.

How Rey end up here – his father use to beat his mother. Was just to keep the woman in check, never to kill. But drunk, the line between manners and murder tend to blur. So, the inevitable happen. When he realize what happen, the man went out back and grab the bottle of Gramoxone. He sit in the tool shed, take one sip – two sips, and then quench his dying thirst. The only thing Rey remember, and vaguely, was the man bawlin out for him. Rey couldn’t remember nothin the man say, just the gargle of rupturing vocal cords as the man try to utter his last words, whatever they was.

Average Trini homicide-suicide.

And just the same, Father Anton take Rey to the sanctuary and show him a photo of his parents. I imagine he has a whole deck of them somewhere in a drawer. I always wonder whose past is held in the aces, and whose is trapped in the jokers. Rey’s reaction wasn’t no different from mine. He just watch the picture, shake his head and pray for deliverance like Father tell him to. Didn’t matter. Didn’t know who them people was. Didn’t care to know.

He only ask because Rico woulda tease him bout it and tell him how he hear his father was a drunkard and a wife-beater. Was a true story, but Rey was tired of Rico knowin more than he did. Rico use to know everybody’s business in St. Asteria, and was always confident in the facts he coulda produce bout people’s lives. How he coulda access the files and know what was in the cards we was dealt was one of the most troubling mysteries.

Rey nudge me with his shoulder and spill the big news, ‘I hear we gettin a new nun end of the week.’

‘Where you hear that?’

‘Just the talk I hearin from Rico and them.’

‘Well, you know Rico know everything.’ I lowered my voice. ‘Boy, I hope she replacing Bulldog.’

In a gurgle of laughter, he say, ‘You wish. Ain’t hear bout she replacin nobody. But hear this. I hear she fresh.’

‘Fresh?’

‘Young.’

‘Young, how? Everybody old here, boy. Them does say Sister Kitty young and she pushin forty.’

‘No, boy. I hear this one now come outta school. And real pretty. Them boys sayin she lookin straight outta one of them Indian movie.’

I raise my eyebrows. ‘So, what day she comin?’

He shrug. ‘I dunno. But Kitty ain’t really take to she, I hear.’

‘Why?’

‘Not sure. That’s just what Rico say.’ He chuckle. ‘Guess what them fellas callin she already?’

He say it slow, restraining a giggle, ‘Sister Mouse.’

And so the trio was complete – we had a Bulldog, a Kitty and a Mouse.

When the next week come round, Sister Mother summon us to the living room. Both the boys and the girls. See, the structure of St. Asteria, the boys live in the right wing and the girls in the left. The upstairs was for the nuns. Father Anton live right in his rectory, at the parish. Never had a night that the nuns was sleepin in any other place than upstairs. They had to live there. No child was allowed to go upstairs unless a nun was with them.

That ain’t stop Rico and Quenton, though.

Them raggamuffins use to go up there all the time. Funny thing was that it didn’t have shit up there. They use to go just because it was against the rules. Rico and Quenton was the two oldest boys in St. Asteria, like fourteen round the time I talkin bout here. They was together in another home before they come to St. Asteria. Was like an asteroid hit Earth the day they come. Sister Mother wasn’t lyin when she say that they suffer a double dose of original sin. The first morning, they come strollin through the halls rapping the lyrics to Pum Pum Conqueror, alternatin.

Rico goin, Pum pum fat, pum pum slim.

And Quenton pickin up, Pum pum bushy and pum pum trim.

Quenton never took off his camo NY cap, because he didn’t want people seein the bald spot above his ear. Rico the redman, claimed he fight and fuck his way outta two other homes before his ass get ship here.

It was because of them two that Sister Mother make the call to bring in another sister, though it take two months to receive a reply to the SOS.

When the junior nun show up the next week, she work up a sweat lugging a fat, old suitcase into the living room, the old leather cracked and peelin from the sides.

I hear Rico whisper to Quenton, ‘Like she have a dildo collection in there, or what?’

Sister Kitty bite her lip and hold back a laugh. Wasn’t sure if it was because of the lewd joke, or if she was just amused watchin the newcomer struggle. Sister Kitty was twine-thin, waist tapering under her habit, skin as pale as the moon. Her eyebrows inclined upward, her lashes thick like beetle legs. She had a bright megawatt smile. In this hot weather, her kohl-black hair stuck to her flushed cheeks, as if patted with a wet palm. For a woman pushin forty, I admit she was quite easy on the eyes – like a pretty lady posing as a nun, rather than a real one. A real NILF, as Rico put it – Nun I’d Like to Fuck.

A title now under threat. Two attractive nuns? Shit, was this a prank or a miracle?

Sister Mother make sure all of us clean up good for the day of the arrival. She douse us with perfume and tie white ribbons in the girls’ hair, not a strand outta place. Spit-polished shoes and white socks pull right up, stretched taut. Yet she keep remindin us that good looks couldn’t trump good manners.

She was standing beside the nun, hands clasped like a vice before her stomach. Was a funny sight. The junior nun was a smurf next to Sister Mother. I ain’t think she woulda be that small.

She looked younger than I picture. Look like she coulda been twenty, if even that. Tiny slits in her cheeks appeared when she smile at us. When she laugh, she scrunched up her bob nose. She had a widow’s peak. That was all I coulda see of her hair. The rest was cover up under the veil. Mostly, when I think bout Mouse on that day, though, I remember her as feathery – like she coulda just drift off with a breeze.

Sister Mother say, turning her chin up to us, ‘Children, this is our new addition to the St. Asteria family. Her name is Sister Maya Madeleine Romany. She was born right here in Trinidad. She enjoys reading the classics, so hopefully some of that can rub off on you. The Lord has brought her to us and we are very grateful to have her here.’

We stood side by side – boys on one side, girls on the next – and we recited in unison, ‘The St. Asteria family welcomes you, Sister Maya.’

She put her hands together and bow her head. She was so enthusiastic, she was blushin. For some reason, I expect her to do a small curtsy. She looked like the type to do them things. She replied, ‘Look at you all, just like little saints. I feel blessed.’

‘You too young to be a nun!’ Ti-Marie shoot out straight away, prompting a swell of stifled chuckles. Even I myself break into a grin. After dolling Ti-Marie up, getting her to wear a dress and gettin each bantu knot in place, we knew somethin was missing – a long stretch of scotch-tape for her big mouth.

As the junior nun part her lips to respond, Sister Mother whip a quick hand up with a sharp shush. The silence was immediate. We wasn’t sure if she was shushing her or Ti-Marie. She then whisper something in her ear. I coulda imagine her tellin her the same thing she tell me: This is a long road that has no turning.

‘Jerrick! Jordon!’ Sister Mother call out. ‘Help Sister Maya with her belongings!’

Rico insist on carrying it by himself. He pull the suitcase up by the grip, draggin it up the stairs, the edge of it clattering against each step, much to the junior nun’s dismay. She was flinching and mouthing, Careful, careful, but the words couldn’t come out.

‘Jerrick!’ Sister Mother finally hiss. ‘Watch your step! Jordon, help the boy! The back must slave to feed the belly!’

I didn’t think I woulda find myself cooperating with Rico after he nearly break my finger a few days back. You know that dumbass game where someone would bend your finger back to your wrist till you scream Mercy! Well, as it happen, I was screamin out, ‘Mercy! Mercy!’ and Rico just keep bending my pinky back until it damn near break right off the joint. Never had no apology. Never ask for none. Play stupid games, win stupid prizes.

We both lift from the ends and haul it up together to her room. Rico take the suitcase and flop it on the bed, and she cringe as it hit the mattress. The room was small and she didn’t look too pleased. The paint was flakin off the wall. Didn’t have no window. We try to fix it up – our mission for the prior two days. Sister Mother assign the directives.

So we scrub and mop that floor, boy. We peel grime from brick. Take the broom to every cobweb and whap the corners till plumes of dust puff up against the walls. We wipe the dresser and shelves till not a speck was in sight – shoulda see them before, powder-up like they was seal away for centuries. Like relics in a tomb, a boneyard. You shoulda see the whole room before, dense and pulsin with grime. Swear it was alive, a throbbing hovel for spiders and lizards.

‘Don’t beat your small wee-wee too much over she, eh,’ Rico whisper to me, though he was the one lickin her with his eyes.

I look at him from the corner of my eye. He nudge me, whispering again, ‘She look like she could get it, though, eh?’

I ain’t say nothin. Don’t expect me to have no response to rubbish like that.

‘You think anybody ever take she before?’ His eyes dart back to her, one side of his mouth curlin up. ‘I feel she never even see one before, boy. Or probably she fraid it. What you think?’

I narrow my eyes at him.

‘Boys.’ Her voice made us recoil.

Rico tip his chin at me and say, ‘That one there is the boy. I ain’t no boy.’

‘Gentlemen,’ she say, smiling. Then she ask Rico, ‘What’s your name again, young man? Jerrick, right?’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ he say, grinnin. ‘But you could call me Rico.’

She just raise her eyebrows at him. Then she direct her eyes at me. ‘And what about you?’

I remember how my throat went dry at that moment. Tryin to talk but strugglin to lift my tongue. For a few seconds, I couldn’t breathe. I was bunch up in a knot, frozen. I close my eyes – had to count to three. Only then the name coulda trickle out from the ice. ‘J… Jordon Sant, ma’am.’

Rico let out a snort. The boy was stupid and smart at the same time. He had already sum up my adoration – my veneration of the new addition to St. Asteria. Probably know it before I did. He was good at sniffin out things like that – piling them together in his arsenal to use against you in the future. If you adore something and you let people find out, you expose a little bit of flesh to the world. Yes, affection is like a wound. Risk of infection come with it.

She smile at me. ‘What do you say – want to help me unpack, Jordon?’

‘All right.’ My response come out in a polite breath.

Turning to Rico, she say, ‘Well, that’ll be all, Jerrick.’

He wasn’t laughin no more. He was standin there, eyes sunken in his skull. ‘You don’t want me to help too?’ He seem genuinely heartbroken. Didn’t think to wonder why at the time. Perhaps Rico was feelin what I was feelin, but he was better at hidin it. Open his skin for the junior nun, probably.

‘No,’ she tell him straight. ‘I’m sure the two of us could manage here. No need to burden yourself.’

‘Burden? Is not a –’

‘That’s an order,’ she say, stern.

‘Yes, ma’am.’ Rico’s tone was sombre, workin hard to slide up the clutch in his throat. He leave the room and stamp step to step down the stairs. After she undid the suitcase latch, she dab a handkerchief on her forehead. She look at me with a nervous smile and say, ‘What was I thinking, packing all this junk, huh?’

She flip the top open and I couldn’t help but peek. Was mostly books and ceramic figurines. Never really care for books before, but I faked excitement over them. ‘Wow, that’s plenty to read.’

‘You recognize anything?’ she ask.

I shook my head. She was asking the wrong child. Poor Father Anton try to encourage everybody to read, but we ain’t never bother. I think he use to feel bad, seeing the study with all them stacks of unread and half-read books – most of them donations, a few of them from his own personal library. All lain to waste.

She stack them into two neat piles on the bed. ‘What’s the last thing you read?’ she ask me, still eyeing the books.

I shook my head again. ‘I don’t really read.’ Guilty as charged. Never felt so bad bout not reading before. Not even when Father Anton and Sister Mother harass me daily that I wasn’t expanding my vocabulary enough. Not when my teacher call me out on not knowin the difference between an adjective and adverb.

Her face went serious all of a sudden. A slight pallor in her lips, with apologetic slowness, she ask me my age.

So I tell her, tracing my toes on the floor, bracing for impact.

She bite her bottom lip. ‘Twelve years and not reading?’

‘I just read the Bible sometimes.’

She paused and let out a small sigh. I know the sound of relief when I hear it. Everybody, every soul that cross St. Asteria, always assume the worst when they see us. They assume none of us could even read, so they never want to ask direct, as if asking is accusin of some kinda sin. As if not knowin how to read is a kinda affront to mankind. At St. Asteria, I guess it was a sin, because all of us had not only had to read, but enunciate the Word of God.

I tell her, ‘Never bother with much else. I never see the real purpose in readin somethin somebody just make up.’ It wasn’t a way to demean her passion. It wasn’t even the truth. It was bait – for her attention. And as she furrow her brow and run her finger down the bookspines, I know she was gon bite.

‘They told me there’s a library here.’

‘The study – yeah.’

I led her down to the study. Really, it was just a few bookshelves, two old couches and a wobbly table. Thick walls, no windows, one door. I sat on the couch while Mouse browse the shelves. Piece by piece, she pile some books, make a stack out of them on the table: Gulliver’s Travels, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Oliver Twist, The Time Machine. She ask me, ‘You read these?’

I shrug. ‘Hear bout them, but never bother.’

‘You wanna start with these?’

‘You mean, read them?’

‘Mm-hmm.’

Oh God, was my first thought. It show, I’m sure, because she then say, ‘Maybe I could lend you one of mine.’ It seem that she was even a little desperate to make a connection. When you enter a dark room, you make sure you ain’t alone, right?

‘Yours?’ I rub my thumbs together.

‘From my suitcase.’ She beckon me to follow her.

When we went back to her room, she sift through the books and produced the thinnest one. The Little Prince. The cover had a boy in pajamas standing on a small planet in outer space, but it didn’t look like a space adventure. As she hand it to me, she say, ‘You’ll like this one, Jordon… There’s one condition.’

‘What?’

‘That book is special to me, so keep it very, very safe. Can I trust you?’

You know, that was something. Not that nobody ain’t ever trust me before. But nobody never trust me with something dear to them. She wasn’t just testing me – she was testing herself. ‘No dog-ears in it, I promise,’ I say, giving her a nod. I held the book against my chest.

‘Oh my, dog-ears? Well, if you do that, I don’t think we could be friends for long.’

Then I help her organize her books on the shelf. I also laid the ceramics on the dresser. Was mostly swans, egrets, ducks. But mostly swans. Some of the other figurines was crafted out of shells. Had all kinda fancy shells. She named them for me – scallops, mussels, whelks, cockles, limpets, angel wings. They was painted and glued together to form frogs, rabbits, cats, all kinda animals.

‘You make these?’ I ask her.

A glint flashed in her eyes. ‘My dad’s a pilot, so he’s been all over the world. Whenever he goes to a new country, if there’s a beach, he’s there. He collects rocks and shells. He doesn’t like to buy them – I think he’d read once that the bigger, fancier shells weren’t collected from the beach. They were taken from animals still alive. He just likes having them.’

‘Still alive? These was living?’

She laughed. ‘Shells are these creatures’ armour, you know. Think about it. That’s what my father told me. He said that we all have our own armour, one way or the other. Do you believe that?’

‘I don’t know.’

She shrug. ‘Well, there were baskets upon baskets of shells at home. One day I got the idea to make animals out of them. This frog here,’ and she held up a frog that was perched atop a mussel and had a scallop shell for a mouth, ‘is from five different countries. You can imagine that? You’re holding different parts of the world in your hand. The grand world in this little frog.’

She let me hold it. As I examined it, I said, ‘I never really hold one before.’

‘A frog?’

‘A shell. Never went to the beach before.’

‘The beach? What!’ she blurt out. ‘But this is Trinidad! Everybody’s gone – .’ Then she stop herself. She purse her lips and click her tongue. I never liked when people stop themself from sayin things round me, as if a sentence or a word could do me wrong. Make me feel like somethin was wrong with me.

We finish lay the figurines on the shelf. As I was bout to leave, I turned to her. She was still, her shoulders suddenly heavy, slumped, staring at the neat row of shell animals. The weight of the world suddenly bear down on her.