Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

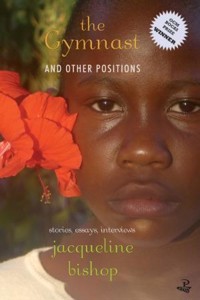

Gloria, living with her mother in a Kingston tenement yard, wins a scholarship to one of Jamaica's best girls' schools. She is the engaging narrator of the at first alienating and then transforming experiences of an education that in time takes her away from her mother, friends and the island; of her consciousness of bodily change and sexual awakening; of her growth of adult awareness of a Jamaica of class division, endemic violence and the new spectre of HIV-AIDS. The novel's strengths lie in the pace, economy and shapeliness of its page-turning narrative; in its poetic descriptions of urban and rural Jamaica; and above all in the quality of its characterisation and the dramatisation of Gloria's relationships with her mother, grandmother and the girls she has always known in her grandmother's rural village, with Rachel, their neighbour in the yard who is Gloria's rock of understanding, and, at the heart of the novel, with Annie, the purest and indivisible love of her adolescent years. "I LOVE The River's Song! It was so hard to put it down! Gloria's coming-of-age story is warm and true and bittersweet. Hers is no wide bridge over the river but a rocky path to womanhood, to friendships made and lost and to the knowledge that love also requires navigation. The River's Song is a song we've all heard before, but never with such force and clarity as this." Olive Senior Jacqueline Bishop was born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica. She now lives and works in New York City, the 15th parish of Jamaica. The River's Song is her first novel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JACQUELINE BISHOP

THE RIVER’S SONG A NOVEL

Sparkling, flashing, gleaming, glowing,

Where no eye can see its rays,

Rests the mystic golden table

Dreaming dreams of olden days.

’Neath the Cobre’s silver water

It has lain for ages long;

And an undertone of warning

Mingle’s with the river’s song.

~ The Legend of the Golden Table

On the dresser sits a frame

With a photograph

Two little girls in ponytails

Some twenty one years back

~ Cindy Lauper, “Sally’s Pigeon”

ForKamara & Demaya

I went to see Annie on my last day on the island. She was sitting on a plain wooden chair in her room, looking out of the wide-open windows at the dark-blue mountains. She turned slowly and looked at me when I walked into the room, a long searching, searing look, before she looked back out the window without saying anything. Her mother, pale and ashen, kept looking from Annie to me, trying, for the umpteenth time, to figure out what had happened between us – just what had gone so terribly wrong. Getting no answer, she withdrew.

Annie looked down at her slender fingers. She turned to look at me again, another searing, searching look, tears rapidly filling her eyes, before she looked back out of the window. It seemed in this one moment that I was saying goodbye to so many people: to a woman named Rachel whom I had loved and who had so loved me; and to the girls, now women, who had all left their mark on me – to Junie, Sophie, Nilda, and that girl Yvette, wherever in the world she might be. I was saying goodbye to my mother, my grandmother, Zekie, the island. But most of all, I was saying goodbye to Annie. Dear sweet Annie.

She tried to say something, but it was too great an effort to get even a few words out. She seemed to be searching for something else to say, before she gave up, and pulled an even tighter veil over her face. She looked down, frail, emaciated, hands trembling in her lap. There was that look again on her face, of deep confusion; something just did not make any sense to her.

I made to go over to her, but found I could not; my feet had grown roots it seemed, down into the ground. She seemed so tiny, so frail. Annie. After that, all I could do was hurriedly leave the room, hurry down the stairs and out of the house, an anguished sob trailing behind me. This is how I remember it, years and years later. This is how I remember it, and why I had to write it down.

CHAPTER I

“I knew you could do it! I believed you would do it!” my mother said, smiling down into my face that she’d just covered with kisses.

The entire tenement yard must have heard her cry of delight as my mother danced around the tiny two rooms we lived in, thumping heavily on the dark brown wooden floor, waking up not only me, but also the insects burrowed deep into the wood. When she was done dancing she pulled me out from under the quilt my grandmother had made for me, when-you-were-a-baby-no-bigger-than-the-palm-of-my-hand, gathered me into her arms and started kissing me all over my face. That morning, the examination results were finally printed in the newspaper and I was one of the girls who received a scholarship to All Saints High School, the most prestigious girl’s school on the island.

Outside it was cool and dark, the sounds of early morning coming into the house through the jalousie windows. Ground lizards shuffled up and down the hibiscus tree outside our door, and the crimson sun was just beginning over the horizon, rising above the dark-blue mountains, which dominated Kingston. As the sun rose, the large white mansions perched on the mountainsides came into view. These were the houses my mother often looked at with desire. One day, some way, some how, we would live in one of the houses in the hills. Then-we-would-become-somebody.

I did not know when my mother left the house to go and buy the newspaper with the examination results. I knew I had passed when I heard her screaming. All night long I twisted and turned in bed, making all sorts of deals with God if he allowed me to pass my common entrance exam. I would stop telling lies and stealing money from my mother’s purse to buy all manner of foolishness. I would go willingly to church every Sunday and there would be no quarrelling with my mother about how I was dragging my foot in the house instead of hurrying off to hear the word of the Lord.

“Come, come and look. Look, right here, under All Saints High School, is your name.”

I rubbed my eyes, blinked, and looked where my mother was pointing her finger excitedly. Underlined twice in red-ink was my name. It was there along with the primary school I attended. A slow smile started across my face. At thirteen years old, and on my first attempt, I had gotten into All Saints. The many months of extra lesson classes, reluctantly leaving my friends on the playing field and heading off to Mrs. Porter’s, had finally borne fruit.

“Come, I have something for you!” My mother took her handbag out of the closet and started rummaging inside. When she didn’t find what she was looking for, she emptied the bag’s contents on the table and started rifling through them. She pushed aside bills, receipts, the green lime she carried as-protection-against-things-evil, a shiny fluorescent metallic-purple make-up kit, before she finally found a small plastic bag.

“This,” she said, “is for you.” She tipped out the contents and there in the soft pink of her palm was a pair of gold earrings: birds in flight – red rubies for eyes, the tips of their tiny beaks a brilliant moss-green. They were the earrings I’d seen a couple weeks before in a jewellery store in downtown Kingston. I had stood for a long time just looking and looking at them. My mother had come up to the window and together we looked at the earrings, before my mother took my hand and slowly led me away. We both knew she could never afford them.

I shrieked and threw myself into my mother’s arms. Laughter bubbled up from a warm soft place inside. Hugging, we danced around the room. I was happy my mother was happy. I was happy to make my mother happy. My mother wasn’t always very happy with me.

“I knew you would do it!” She gave me a long satisfied look. “I just knew you would! Girl, I’m too proud of you! Now we’ll have to send a letter to your grandmother to let her know the good news, though I suspect by the time the letter gets to her, she’ll have heard it already – your Grandy has a way of finding out these things!”

This used to surprise me, how my grandmother would turn up just when my mother was at her wits end and needed her the most. When I was feverish and sick and my mother was distraught and crying, not knowing what to do, I would look up to see Grandy’s cocoa-brown face bent low over mine. When I was younger, Grandy would visit at least once a month, but she didn’t come as often any more; her arthritic feet gave her more and more problems Still, every now and again she made her way to the city to see us and I still spent all my summer holidays with her in the country.

When Grandy found out I’d passed my exam, she’d be as pleased as my mother, maybe even more so; she was forever telling me that if I wanted to become somebody-in-this-here-Jamaica-place I had to go to high school; if I did not go to high school, dog already eat my supper.

“Your grandmother will tell all of her church sisters! Everyone within a one-mile radius of her front yard will hear about you – her bright-bright granddaughter who get scholarship! Perhaps,” my mother finished, on a quieter, more ominous note, “one of us will complete her education at All Saints High School!”

I looked closely at her, hoping she wouldn’t fall into one of her moods when she blamed me and my father for not becoming the doctor she always wanted to be; not having her house in the hills. My mother had been going to All Saints, was in her last year when she met my father who twisted up her head, turned her into a fool and, before long, Mama was in-the-family-way. She was forced to leave school, and that was not the worst of it, for she had to fight with my father to acknowledge me. There was a steely determination in her face, as she repeated, “One of us will graduate from that school!”

There was a loud knock at the door.

“Who is it?” Mama called.

“Well, who do you expect it to be?” a woman’s rough voice called back good-naturedly. “Is only me, Rachel! Let me into the house before I freeze to death out here in this cold morning air!”

Rachel was Mama’s best friend in the yard and I knew, sooner or later, she would turn up at our door.

“Don’t tell me,” Rachel said, “Gloria pass her examination!”

Rachel was a short stout woman, very dark, wearing a pale-pink nightgown over which she’d thrown a sheet to ease off the cold. Most of the women in the yard did not like Rachel because she was a “night-woman”, but Mama was friends with her, even over my grandmother’s objections.

“After all,” my grandmother would say in one of the heated arguments that erupted over Rachel, “You know what she does for a living! If you not careful, people might start thinking you do the same thing too!”

“When I was sick the other day, she was the only person in this yard who came to see how I was doing. Even made dinner for Gloria and me. Take her good-good money and buy us parrot-fish for dinner. I could’ve been dead and none of those other people came to see what was going on with me, let alone make us dinner. I telling you, Ma’ Louise,” Mama raised her voice so the other people in the yard could hear, “Rachel is the only genuine person in this place!”

“Just a little flu, nothing much!” my grandmother replied. Then, as if she’d heard what Mama said for the first time, Grandy turned to her and asked, in a fierce whisper, “ You mean to tell me you eat from that nasty-dirty woman? You mean to tell me you put the food she give you into your mouth?”

“What make her nasty, Ma’ Louise?” Mama was really angry now. “Her dishes always well clean, she carry herself neat and tidy. Her house even cleaner than mine! What make her so nasty?”

“You know what I mean.” Grandy lowered her voice so I wouldn’t hear what she was saying. “All them mens.”

“She combed Gloria’s hair, ironed her uniform, and got her off to school for me for two whole weeks. That’s all I care about!”

“Still,” Grandy insisted, “she’s not the type of person you should be associating with. You have Gloria to think about! You have to set an example for your daughter!” They both looked over at me, sitting at the table by the window, fiddling with my homework, pretending not to be listening to what they were saying, though they knew full-well I was listening to every word that came out of their mouths, and they both ended the conversation. Once I was outside the house the argument would begin again.

I loved Rachel. It was not only that she helped us out when Mama was sick; even before that she always had a kind word or a fruit for me. She smiled at me at the standpipe and always put me in front of her when we were in line to catch water. I knew a lot of sailor-men came to visit her when their ship was in on Thursday evenings, that everyone talked bad about her because of this, but that didn’t matter to me. As far as I was concerned, people in the yard were just jealous of Rachel because of the pretty things she had in her house. Her bed was always made up with a silk and lace bedspread from abroad; her floor was polished a bright red colour, and there were the flowers, the plastic flowers of many different colours she bought in the flea market downtown and arranged over her bed, around her dresser, in the cracks in the walls. And there were the postcards, lots and lots of postcards, from the sailor-men after they’d gone back home.

Whenever she got a new postcard Rachel would call me over to read what it said. I would carefully pronounce every word, telling her exactly what was written. Sometimes, when something in the card was to her liking, Rachel would laugh out loud and ask me to read again what her suitor had said. She’d then say it over and over to herself as if committing it to memory. She listened carefully to every word that passed my lips and if the tone of the letter changed, she abruptly ended the letter-reading session, saying we were getting into big-people-things and she would ask one of her big-people-friends down at the wharf to read the rest for her. She never failed to compliment me on my reading and encourage me to continue doing well in school. A kind of sadness would come over her then, and one day she said to me, “Yes, if there’s one thing I would encourage any young woman to do, it’s to do well in school.”

“Yes!” Mama waved the newspaper at Rachel, “Gloria pass her common entrance for All Saints High School!”

“Well this is good news!” Rachel passed her eyes briefly over the newspaper before turning to flash me a big broad smile. “Is no surprise to me you passed your examination, Gloria, for everybody know you’re a very bright little girl. Still, this is well done, well done of you!” and she took her hand out from under the sheet and handed me a navel orange before pulling me into her arms.

I loved going into Rachel’s sweet-smelling arms almost as much as into my mother’s. I would lay my head against Rachel’s chest and listen for the steady, even beating of her heart, as I sometimes did with my mother. Just the sound of her heart pounding steadily away gave me the most comfortable feeling in the world.

“You must be the only child in this yard who pass her common entrance examination. Everybody will be jealous of you, but most especially Miss Christie who believes her Denise is the brightest and best thing around town, although we all know differently. There is reason to celebrate today, if not too loudly. Gloria, you did well. You did very, very well.” She wrapped her arms so tight around me the many gold bangles she wore jingled loudly.

“But you don’t think…” my mother stopped, “you don’t think nobody would try to do anything to Gloria?”

By “anything” she meant – would someone put an awful curse on me so I would die a frighteningly horrible death before I even started attending All Saint’s High School? Would I suddenly get an itch, scratch it, and have the itch turn into a sore that would never heal? I could see the thoughts racing around my mother’s head. After all, her face seemed to say, bad-minded-people put a curse on her father when he came back to Jamaica from Panama with all of his Colon money – and look what had happened to him. The young-green-man had fallen down dead one day, for no reason. No reason at all. Bad-minded-people.

“I tired telling you,” Rachel said, exasperated, “obeah only catch you if you believe in it.”

Mama shook her head from side to side. “No,” she said softly. “Obeah can catch anybody. Even those who don’t believe in it …” Before Rachel could utter another word Mama was in the kitchen, rummaging around for a lime to cut and sprinkle around the room.

Later that day I was the talk of my primary school and my class teacher took me to the principal’s office. The principal leaned back into his swivel leather chair behind a large desk, and smiled at my teacher. Framed certificates hung on the walls – all the schools he had attended in England and Canada.

“Well, well, well,” he said, leaning over his desk and reaching out a hand to me, “ if it isn’t my little spelling bee champion. And today, Gloria you’ve put our school on the map again, so to speak. You’ve made us proud.” The Gleaner was spread out on his desk and my name and the name of the school circled in red. I was the only student from the school to pass the common entrance examination.

My teacher gently pushed me forward. All morning long she repeated how bright I was to the other teachers who came to the classroom wanting to meet me; she had known I would pass. She had been keeping her eyes on me, and this was no-surprise, no-surprise-to-her at-all!

The principal cleared his throat and sat back in his chair. “I wish I had more students like you in this school, Gloria,” he was looking out the door to the playground. It was recess and children were tumbling over each other, playing on the jungle-gym in the yard. When we got back to the class it would be all about who’d lost a ribbon, or who’d broken a brown bandeau an aunt in America had sent for her. Looking out at the playing field it suddenly hit me with a tremendous force that I was leaving this school where I’d spent the last nine years of my life. I knew all its secret hiding places: where the sixth grade boys took the sixth grade girls to push them up against the walls and feel under their blouses (not even the Principal knew where that was!); the battered old water fountain where it was rumoured ground lizards lived; and in the middle of the school, the garden where students grew large smooth eggplants no one ever ate ( I could never understand why we grew them in the first place). Suddenly my future loomed large, dark and uncertain in front of me.

In my new school I would be wearing a four-pleated box skirt and a cream-coloured blouse edged in burgundy – not the navy blue tunic and white blouse I had worn all my life. I would not be free to pick and choose whichever shoes I felt like wearing, but would be required to wear dark brown shoes with dark brown socks every day. And there would be all those students I did not know. Students from preparatory schools. A bubble started forming in my throat that kept growing larger and larger. My eyes began to sting and burn. Before long, the walls of the principal’s office dissolved in tears. Already change had begun to set in. This morning as I’d walked into class, an eerie silence settled over the entire room. I didn’t know what to make of the silence. Were my classmates happy for me? Were they sad for themselves? I made to walk over to the group of girls who’d been my friends for the past six years, but they closed the circle and left me standing outside of it. One of the girls, Raphaelita, a girl who had stayed at my house when her parents first left for New York, whispered, loud enough for me to hear, “And I guess she thinks she’s all that!”

The group broke into laughter.

“I’ll be going to New York soon, anyway,” Raphaelita bragged, “and I don’t need to go to any stupid high school in Jamaica!”

I turned from Raphaelita to Natasha to Nicole, but they all screwed up their faces, letting me know I was no longer welcome in the group. The tears came and I started fumbling in my pocket for the handkerchief I usually carried, but it wasn’t there. I was making such a mess of everything.

“Come now, Gloria,” the principal said, coming from behind his desk and putting a heavy arm around my shoulders, “this is a day of celebration, not tears. You can always come back to visit us, you know.” He handed me his handkerchief. “In fact, I insist on it. Promise me you’ll come back to see us. Right, Miss English?” he said, looking over at my teacher and winking.

Looking at the principal through the heavy curtain of my tears, I suddenly did not care if he was really a rum-head as most people said he was, that he could be found singing loudly in bars all over Kingston every Friday night after he got paid. I didn’t care if Miss English acted more English than the real English people did, pretending she couldn’t speak or understand a word of plain Jamaican patois. I was suddenly ashamed of the times I joined in the laughter and made fun of the way she walked, her two knees knocking against each other. None of this mattered any more.

When I got a hold of my crying the principal handed me a brown paper bag. Inside were three books: two Nancy Drew mysteries (my absolute favourites!), and a book by someone I did not know, an H.G. De Lisser, who, the principal said, was from Jamaica. I took the books out of the bag and ran my hands over the hard covers, tracing the spines. In my mind I could see the words tumbling over each other, swift like the river near Grandy’s house after a hard shower of rain. I would read each book twice. They would become part of my personal stash. I would never lend them out.

“Thank you so much,” I finally managed to say and smiled up at the principal.

“You’re very welcome!”

It was the end of April. Before long I would be off, spending my summer holidays with my grandmother in the country. Sophie, Monique, Junie and that girl Yvette were all there. Plus there was Nilda and Denise in my yard. Who needed the girls at school anyway?

Three women were standing outside the yard, talking, as I walked home from school that evening: Miss Christie, Nadia Blue, and Miss Sarah.

Miss Christie lived in one of the cottages in the back of the yard near the standpipe with her daughter Denise who’d just had a baby. Five years ago when Miss Christie moved into the yard, everyone wondered who this yellow-skinned green-eyed woman with her red-skinned hazel-eyed daughter was. It was obvious she came from some kind of class and standing. Gradually the story came out and Mama’s sympathy was rewarded with a performance.

Miss Christie had disgraced her Upper St. Andrew family when she got pregnant by a married man, a well-known businessman much older than Miss Christie who made sure both she and their daughter were well taken care of. While he was alive, Miss Christie lived in an apartment in New Kingston with helpers to take care of their every need – Denise attended one of the island’s best preparatory schools.

During this time Miss Christie kept pressing the man to leave his wife; to marry her. “Karl, I can’t stand this life I leading any more! You and I both know you no longer love the old witch you call a wife – if you ever did. So why don’t you leave her? Why don’t you just pack up your things and move in with us?”

“In time,” Karl kept promising. But the man never left his wife, and after a while Miss Christie got used to him staying with her a couple nights and going home the other nights. Over the years there were many terrible fights with the wife who accused Miss Christie of being a home-wrecker, of flaunting in her face the many things Karl bought her. Worst was the time the wife found out where she lived and turned up at the apartment in New Kingston.

“You will never get him!” The wife flung at the closed door, all the neighbours looking out. “If you think you’ll ever get him, you’re dreaming some kind of dream.”

The wife was a tiny Chinese woman, no more than five feet tall, and Miss Christie had been surprised how loud her voice could be. She’d let the woman carry on outside her door for as long as she could, hoping she would get tired and go away, but after a while she saw that if she wanted the woman to leave, she’d have to shame her in front of the people gathered outside.

“I have him more than you do!” The wife brandished her gold wedding band. “What you got to show for yourself? If you had any decency, any decency at all, you would let this married man alone and his children!”

“I got this apartment to show!” Miss Christie replied triumphantly. “I have this apartment, the car outside, all the furniture I could possibly want and a bank book full of money!”

“You think so eh?” The wife was frothing at the mouth. “Well, I will show you who have this apartment! I will show you who have the car outside! I will show you who really own the furniture inside of that house! As for the bank book full of money!”

The wife was close to tears. She could not believe Karl was doing this to her. Her father had made Karl, had given him everything he now had, and this was how he had chosen to repay her? When she first brought him home, her family nearly had a heart attack. A black man. Lin had brought home a black man. And not even a nice brown-skin black man, but one as black as midnight. They tried talking her out of it. Asked her to consider-the-consequences-of-her-actions. The “confusion” of any children. The-difficulty-of-fitting-in. But Lin turned out to be more stubborn than even they knew. Stuck by Karl, bore him five strong boys (whom the grandparents now adored), and her parents had given Karl the money he needed to start his now-flourishing business and this was how Karl had decided to repay her? Karl would be sorry. So very sorry.

Miss Christie was not prepared for what happened next. In fact, she hinted late one night to my mother, when they were both sitting outside on the verandah and talking, it was down right suspicious. For the strapping healthy man just keeled over one day in his office and died. Not even one month later. His secretary came in and found him with some green thing coming out of his mouth.

“Just like that?” my mother asked, incredulous.

“Just like that,” Miss Christie replied softly.

Again the wife showed up at the house. The pale freckled hand with its gold wedding band up against the window. Karl had made no provision for Miss Christie or for Denise in his will. In fact, there was no will, and the apartment and the car were in her husband’s name. As for the furniture and the bank-book-full-of-money, that Miss Christie could keep, for that would go so quickly from a woman who only knew how to work on her back. The wife stood guard at the door with six police officers as Miss Christie was forced to move out of the apartment. This was how she eventually ended up in the yard. Miss Christie was crying by the time she finished telling my mother the story, and my mother was quiet for a long time, no doubt recalling a similar incident with my own father. Mama reached over and took Miss Christie’s hand.

“It happens to the best of us,” she said, sighing. “At least you knew there was a wife. Some of us didn’t even have that luxury.” They said nothing else the rest of the night, and I don’t know how long they stayed out there like that, because, after a while I stopped my eavesdropping and fell asleep.

Everyone expected my mother and Miss Christie to become firm friends since they were the only two women in the yard to have gone to high school, but this friendship never came to fruition. For one thing, Miss Christie was always in some kind of competition with my mother, always trying to one-up Mama in conversations. She kept insisting she knew more about everything than anyone else in the yard. After all, she had travelled abroad a few times, thanks to Denise’s father. To make matters worse, Miss Christie had taken an instant and total dislike to me, because of how bright people said I was.

When I was younger my mother sometimes left me with Miss Christie when she went to work. Miss Christie took away my lunch and put me to stand in a corner for the stupidest reasons.

“You might be a little princess for your mother,” Miss Christie would say, “but you are not any princess for me!”

If she happened to be watching several other children, Miss Christie would organize a reading or spelling contest. It always came down to a race between myself and Denise, who, truthfully, always seemed bored with these contests. I always ended up winning, much to Miss Christie’s dismay and once she left me standing under the tamarind tree where red ants bit me all over my legs, causing them to swell up badly. By the time my mother came home my legs were so swollen they looked like two tree trunks. That night, when my mother asked me what happened, I told her everything Miss Christie had ever done to me in my life, and my mother stormed out of the house and gave Miss Christie a good cursing out! That was the end of their blossoming friendship.

The other woman, Nadia Blue, lived at the front of the yard, across from the mad woman who collected bottles and cans on her daily trips around the city and hung them on the shrubs growing wild in front of her house. Nadia lived with her man, Jesus, and their five children. Jesus and Nadia were forever quarrelling and fighting because of all the other women Jesus had. It seemed every few months someone was either pregnant or just had a baby for Jesus.

Jesus’ dream was to make it to America, to New York, where he would make so much money he could live like all the foreigners and drug dealers who flocked to the island during the Christmas holidays. Jesus would buy a car; no, more like a whole fleet of cars with the money flowing like milk and honey on the streets of New York. He would drive around in style and be treated like the don he really was. He would take care of Nadia and all his other baby mothers. Nadia wouldn’t have to take in other people’s clothing and scrub and wash them until her back ached and her fingers were pale and wrinkled from constantly being in the water; the children would have everything they needed. He would lavish special attention on Nadia, for even though he had several other baby mothers, Nadia was his main woman. She was the one he worked the hardest to get, they’d been together the longest, and they’d been through the most together.

“I don’t care how pretty a woman thinks she is,” Jesus was fond of saying, “she can never come before my Nadia. Nothing in the world can ever separate us, for no matter what, my Nadia not leaving!”

And he was right about that; for all they quarrelled and fought, Nadia would never leave Jesus. She had been with him from the time she was sixteen years old when she’d moved out of her mother’s house just to be with him.

The last woman was Miss Sarah who lived in the yard before it was a yard, had lived there when the place was open land where stray goats pastured. She was an old woman with thinning gray hair, but still surprisingly sprightly for her age. She knew everybody’s business: which young girl was pregnant even before she started to crave green mangoes with salt, and who the girl was pregnant for even when she was trying to keep the man’s name quiet. She had a daughter in England who regularly sent her money and kept promising to visit but never seemed to make it. It was rumoured that Miss Sarah had this daughter with a sailor-man, that in times gone by she had been no different from Rachel, but Miss Sarah vehemently denied this. Her daughter’s father, she always insisted, was a respectable white gentleman with whom she’d lived for several years. When they broke up, he took the child back with him to England.

“Good evening Miss Sarah, Miss Christie, Nadia.”

“Well, well, well, if it isn’t the little bright spark who passed her examination,” Miss Sarah said. “I stayed clear round the back and heard your mother this morning.”

“What school you pass your examination for?” Miss Christie wanted to know.

“All Saints,” I mumbled. Miss Christie always made me nervous and uncomfortable.

“Oh,” she could barely conceal her surprise.

“That is good, really, really good,” Nadia started smiling down at me. “I hope one of my girls will get into a good school like that. Perhaps Nilda will go to a school like that. She didn’t pass this time, but there’s always next year ...”

Miss Sarah began shaking her head in amazement when she heard the school I was to go to. “You so bright! So very bright!” I could hear the affection in her voice.

“These girl children,” Miss Christie sighed heavily, “they can be such a disappointment. Such a disappointment. If Denise had been studying her books instead of studying how to get a baby I am sure she would be going to that school today. But they are such a disappointment these girl children, and you can never tell what will eventually become of them, even when they start out young and full of promise.”

Miss Sarah took the chewing stick she was munching on from her mouth and sent a stream of white spittle flying out in front of her.

“Stop all this right now, Miss Christie! Your Denise was always too force-ripe for her age. And everybody know she not nearly as bright as our Gloria here. I have no qualms about saying Gloria is the brightest child in this yard, maybe even the brightest child around these parts. And she well-behaved and mannersable too, even if we don’t like some of the friends she keeps.” Miss Sarah winked at me and the other two women started laughing. Miss Sarah reached down in the pocket of her housedress, pulled out a bill and handed it to me.

“I’ve been waiting to give you this all day. Give the money to your mother to put in your piggy-bank for you. She pass here not too long ago with a bag of pig tails and red beans, so I know she cooking stew peas and rice for dinner tonight!”

Immediately I was hungry. Stew peas and rice was one of my favourite meals. One I hadn’t had in a long time.

“Thanks for the money, Miss Sarah,” I said, walking away.

“It’s nothing at all. Nothing at all. You a good child.”

“And you must come and help Nilda when her time come to take the exam again next year,” Nadia Blue said after me.

Not a word came out of Miss Christie’s mouth.

As I approached our house the smell of pigtails drifted out into the yard and enveloped me. I could make out the thyme, pimento and escallion Mama put in the stew. I stepped into the house and Mama smiled over at me from the tiny kitchen.

“Guess what? Mean old Rutherford let me out early today so I could come home and make a special dinner for you. He said congratulations to you on passing your exam, old cruff that he is.”

For the first time in a long time, Mama looked young, happy and carefree. She was wearing a T-shirt and a pair of faded denim shorts and had a big cooking fork in her hand. Her hair was not up in a severe bun as it usually was, but down around her shoulders. There was an unmistakable sparkle in her eyes.

“Come here!” She called me over to the pot, as if she had a big surprise on the stove. I pretended Miss Sarah had said nothing to me and feigned surprised when I saw the tiny white dumplings floating up over the pink pigtails and red kidney beans.

“That’s not all,” Mama continued, seeing the look on my face. “I’m making soursop juice sweetened with condensed milk and nutmeg just the way you like it. Change out of your uniform and help me set the table. Put on the white tablecloth with the gold-flowered embroidery. Tonight we celebrating!” She blew me a kiss before turning back to the pot.

Usually I grumbled whenever I was given additional chores, but not today. I put down my school bag, took off my school clothes, and started doing what my mother had asked me to do. Yes, tonight we were celebrating!

CHAPTER 2

Grandy came a few weeks later, bearing gifts as usual. This time it was star-apples, june-plums and sugar cane. Whenever she came, Grandy brought all the fruits in season and I always hurried home from school when I knew she was there. Today, as I came into the yard, I spotted her sitting on the verandah, almost hidden by the hibiscus tree, rocking in the rocking chair. She was eating a piece of sugar cane and fanning herself, and her face broke into a huge smile when she saw me.

I stood for a moment just looking at her. Mama and Grandy looked so much alike! Same high wide forehead and bushy “Indian” eyebrows. The only difference between the two was their weight: Grandy was much heavier than Mama, with an ample bosom I secretly believed was made for me to rest my head on. I made a mad dash for the verandah and stood before her.

“Just you look this bright girl that pass her common entrance examination!” Grandy said, eyeing me. “Just you look this bright girl that going to All Saints High School! Come now and give your old Grandy a kiss.”

She pulled me down into her lap and I buried my face in the side of her neck and the chair rocked harder as she laughed and laughed. Grandy had a smell all of her own. A kind of fresh country smell, doused in rosewater. Grandy handed me a piece of sugarcane from the plate beside her. The emerald streaks through its dull yellow colour gave promise of just how sweet the cane would be. I bit into it and my mouth immediately filled with the sweet juice.