2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Youcanprint

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

La Saga dei Roesler Franz è un viaggio intimo e intenso nella storia della famiglia Roesler Franz che si è trasferita nel 1747 da Praga a Roma dove aveva la proprietà dell' Hotel d'Alemagna in via dei Condotti nel quartiere cosmopolita della città, come venne definita la zona di piazza di Spagna da Giacomo Casanova. Nella storia della famiglia il personaggio più importante è sicuramente Ettore Roesler Franz, artista che ha saputo catturare nei suoi acquerelli l'essenza di una Roma che stava scomparendo sotto i colpi del mattone per rendere Roma la capitale del nuovo stato italiano. Questo libro è molto più di una biografia: è infatti, un affresco storico e culturale, una meditazione sulla natura dell'arte e sulla capacità di essa di resistere al trascorrere del tempo. Ettore Roesler Franz, attraverso i suoi acquerelli, ha fermato il tempo, catturando la bellezza fugace di una Roma in trasformazione. Il suo progetto principale, " Roma Sparita ", è un ponte tra passato e presente, un legame visivo tra la città eterna e le sue metamorfosi. Ma è anche la storia di un uomo e del suo inquieto peregrinare nel mondo dell'arte, una vita di passioni, disillusioni e ricerca costante della bellezza.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Contents

Titolo

Diritto d'autore

Introduction

Preface

Esoteric preface

Part I

Friedlant

The duke Albrecht von Wallestein

The Church of the Holy Cross in Frydlant

Rudolf II

Prague

Theresa

The Rosicrucians

The True Story of Teresa

Travelling to Rome

Rome

The Alemagna Hotel

Franz’s death

Freemasonry in Rome

Goethe and the Roesler Franz

Goethe, Andrea Massimini and the Arcadia Academy

Roman Republic

Giuseppe and Costantino Roesler Franz

Rome Restoration and Carboneria

Piazza di Spagna and the English Quarter

Part II

A rude awakening

The return of Constance

His name will be Ettore

Destiny in the stars

A banquet to remember

Roman Republic

Adolfo’s birthday

Farewell to little Giuseppe

The Tacca bas-relief

The Ciocci family and Chateaubriand

Maria Costanza Teresa and Costanza

A holiday at my aunt and uncle’s

Distinguished guests

The arrest of Francesco

The first day at the Academy

A Great Friendship

Nazzareno Cipriani

The British Consul

The British Consulate

A distinguished guest

Alessandro and Carolina’s wedding

20 September 1870

From the consulate to the bank

In Naples

Enrico’s disaster

Part III

Air of change

On the banks of the Tiber

An ante litteram leaflet

The charm of the Appia Antica

Villa of the Quintili

Lunch with Ernesto Nathan

Looking for Miriam

Princess Olimpia Pallavicino

A sweet Umbrian holiday

The Esteem of Ferdinand Gregorovius

Three sudden deaths

Keats’ tomb and the Severn burial stele at the Non-Catholic Cemetery at the Pyramid.

Part IV

Tivoli

Villa d’Este and Franz Liszt

The visit of Enrico Coleman

Between cafes and artists

Lucky at cards, unlucky in love

In the marshes of Maccarese

The hunting baptism

The first series of Roma Sparita

The meeting with Quintino Sella

Return to the Ghetto

Miriam

Ettore and England

The statue of Giordano Bruno

Realism and Symbolism.

Aunt Costanza’s suicide and the stay in Tivoli

Evelina

Aqueducts

Catherine

Part V

New life

British princesses

Roma Disappeared II and III Series exhausting negotiations for disposal

Duilio Cambellotti

The portrait of Balla

The disciple Adolfo Scalpelli

Honorary citizenship

The Feast of Pèsach

The new synagogue in Rome

On the road again

London Memories

The letter to his nephew Luigi

The letter to Ettore Ferrari

The farewell

The will

Acquisition of the Second and Third Series of Roma Sparita

What happened to close friends and family after the death of Ettore Roesler Franz.

Arturo, Francesco, Luigi e Alberto

Luigi Roesler Franz

Racial Sanctions, Persecution against Freemasonry, Jews and Rotarians

Adolfo, Anton Giulio e Giorgio Roesler Franz.

Wedding of Anton Giulio Roesler Franz and Giuliana Lolli

Postface

Indice

Guide

Copertina

Indice

Start

FRANCESCO ROESLER FRANZ

The Roesler Franz saga

The fictional story of the familyof Ettore Roesler Franz, the painter of Vanished Rome

Youcanprint

Title | The Roesler Franz saga

Author | Francesco Roesler Franz

ISBN | 9791222760018

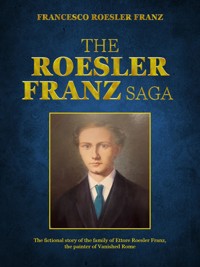

Cover: Portrait of Ettore Roesler Franz, tempera by Ettore Ferrari 1863

Back cover: The Colosseum watercolour by Ettore Roesler Franz

Website: www.francescoroeslerfranz.com

Website: www.ettoreroeslerfranz.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/EttoreRoeslerFranz/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ettore.roeslerfranz_art/

© 2024 All rights reserved by the Author

No part of this book may be reproduced without the prior permission of the Author.

Youcanprint

Via Marco Biagi 6 - 73100 Lecce

www.youcanprint.it

To my motherand my sister Anna Maria

INTRODUCTION

Some fifty years ago my mother, who was a psychic, while watching Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrook saga on television, that one day I would write my family history: I burst out laughing in her face, incredulous. Instead, she was right that time too and therefore I decided to publish this book this very year on the centenary of his birth.

My father told me that, when he was a child, every morning before going to school his nanny in English repeated to him: “Remember Anton Giulio, don’t forget, you are a Roesler Franz.”

Dad only told me this once and I have never forgotten and I hope this saga serves to remember my ancestors and in particular my great uncle Ettore, the painter of Roma Sparita.

I owe a debt of gratitude to my ancestors, in particular my sister Anna Maria, who died before I was born, and who guided and protected me in my life, as I came close to death at least a dozen times.

Also included in this saga is a revised and updated edition of the fictional biography on the life of Ettore Roesler Franz published in 2017 by Intramoenia, which, compared to the first edition, has been enriched d with all the new features that have emerged in my research in recent years.

Anna Maria Roesler Franz

PREFACE

“The Saga of the Roesler Franz” is an intimate and intense journey into the history of the Roesler Franz family who moved in 1747 from Prague to Rome where they owned the Hotel d’Alemagna on Via dei Condotti in the cosmopolitan quarter of the city, as the area around the Spanish Steps was called by Giacomo Casanova. Important international intellectuals, artists and musicians such as Goethe, Stendhal, Wagner and the Bonaparte family stayed in this hotel.

In the history of the family, the most important character is certainly Ettore Roesler Franz, an artist who was able to capture in his watercolours the essence of a Rome that was disappearing under the blows of brickwork to make Rome the capital of the new Italian state.

This book is much more than a biography, it is, in fact, a historical and cultural fresco, a meditation on the nature of art and its capacity to resist the passing of time.

Through his watercolours, Ettore Roesler Franz has stopped time, capturing the fleeting beauty of a Rome in transformation. His main project, ‘Roma Sparita’, is a bridge between past and present, a visual link between the eternal city and its metamorphoses. But it is also the story of a man and his restless wanderings in the world of art, a life of passions, disillusions and a constant search for beauty.

The book takes us through the streets of a changing Rome, among alleys, squares and views that have become part of the collective memory through the eyes of Roesler Franz. The narrative unfolds following Ettore’s thoughts, experiences and feelings, revealing the depth of his relationship with art and the city.

When we look at one of his watercolours, we see not only the Rome that was, but also the Rome that could have been; this is the power of Ettore’s art, to preserve not only images, but also dreams and aspirations.

The emotional and artistic crisis, aggravated by the lack of recognition of his genius during his lifetime, is a powerful reminder of the artist’s fragility in the face of the changing currents of taste and public opinion. His bond with Miriam, a lost love that lives on in his works, adds a further layer of emotional complexity to the narrative.

The climax of the tale, the death of Hector, marks a bitter but necessary turning point. His death is not only the end of a life, but also the moment when his art is finally recognised and celebrated, a bitter irony that highlights the conflict between art and its value over time.

“The Saga of the Roesler Franz” is a work that speaks to the heart and mind, inviting readers to reflect on art, history and the human being’s ability to leave an indelible mark on the world. It is a tribute to the city of Rome and to one of its most visionary artists, an invitation to rediscover the hidden beauties in the memory of a city and in the life of a man who made them immortal.

Retracing Ettore’s footsteps, we come across a Rome that lives and breathes in his works, a Rome that, although disappearing under the blows of inexorable progress, remains eternal in its essence thanks to the genius of this extraordinary artist. His life, steeped in passions, sorrows and triumphs, reminds us that every artist, in every age, struggles to leave a lasting imprint, a legacy that survives the oblivion of time.

Through reading these pages, we are invited to reflect on how deeply art can touch our lives, changing the way we see the world and leaving an indelible mark on the fabric of our existence. This book is a precious gift, a bridge between the past and the present, inviting us to look beyond the surface of art to discover the treasures hidden in the human soul and in history.

ESOTERIC PREFACE

by Luca Rocconi

Writing a preface is a very arduous task, tantamount to a declaration of intent of the text that follows it: to present readers with the origins of the literary creation, the methods and aims that the author sets out to achieve, all in a few clear, light and non-tendentious lines. This preface (from the Latin praefatio, ‘to preface, to say before’) is not written by the author, but is allographic, written by a third person, who was asked for an esoteric preface, given the nature and content of the pages that follow. Out of my love for esotericism, therefore, I will briefly explain the meaning of this term: it derives from the Greek language, from ἐσώτ∊ρος (exóteros, inner), and represents the ability to go beyond outward appearances, to access the core of inner truth. The main task of the esotericist is to ask the why of things and not to stop at the who, how, when and where. Esoteric disciplines are the spiritual disciplines, Kabbalah, alchemy, hermeticism, magic and astrology, and these disciplines are examined in the book by my good friend Francesco Roesler Franz. Writing an esoteric preface is indeed a difficult task, but to be able to introduce readers to the characteristics of this work through this succinct ‘inner preface’ is also a great honour.

Through reading this book, one not only learns about the history of the Roesler Franz family from its Bohemian origins, but is also transported to the cultural circles and courts of Europe from the 16th to the 8th century. The author brings to life the historical context of the alchemic circles of the Prague court of Rudolf II, where the most interesting minds of Renaissance Europe met: the great English magician and alchemist John Dee, the famous German alchemist-physician Michael Maier, the kabbalah expert rabbi Judah Loew and the astronomers-astrologers of planetary fame Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. Giordano Bruno also stayed at the court in Prague for six months.

As family events unfolded, interconnected with the historical events of the time, the Roesler Franz family’s ties with members of Rosicrucian circles, Freemasonry, Carbonry, the Dante Society and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood deepened. Of all these initiatory societies, the fundamental stages and symbolic instruments are traced, which have art as their main channel of transmission. A true initiatory path is outlined that starts with the young Hector’s cultural education and continues through friendships, encounters, multiple trips abroad and, above all, the role that membership of Freemasonry played in his life.

The Saga of the Roesler Franz is the story of the family from Prague who were among those who founded Freemasonry in Rome in the 18th century. In Freemasonry, initiation is fundamental, a term that derives from the late Latin initiare and means “to initiate into the mysteries””, only later becoming a generic verb relating to any beginning. In turn, this Latin verb derives from i¬ni¬tium (in+i¬re), “to go towards” or “to enter”. Initiate is the verbum of true alchemists, indicating the passage from one state to another of matter, the evolution of the spirit through rites of passage.

The life of the protagonist, Ettore Roesler Franz, is examined as if it were an initiatory journey in the continual search for truth, in the Greek sense of the term. ‘Truth’ in Italian derives from the Latin veritas; this Latin word comes from the Balkan and Slavic area and means ‘faith’, ‘trust’, and thus refers to a concept to be accepted passively, by faith, relying on an institution or religious dogmas. It is not veritas that an initiate seeks; but aletheia (ἀλήθ∊ια), the Greek term for truth, has a different structure than the Latin expression veritas. Etymologically, the prefix alpha (α), with a privative function, precedes the root leth (λήθ) which means forgetting; from the same etymological root also derives the name of the river Lete, which in Greek mythology is the river of oblivion. Aletheia therefore indicates something that is no longer hidden, that has not been forgotten, it is truth understood in the sense of revelation and unveiling, it is the process of knowledge that is realised through the removal of the veils of Maya of Vedic memory.

In ancient Roman society Janus/Ianus was the god of initiations, the guardian of all forms of passage and change, the protector of all that has an end and a new beginning. The symbolism of Janus is represented by the door (ianua) and the keys. Janus was considered the inventor of the keys, and for this reason he was the patron god of the craftsmen’s guilds, the Collegia Fabrorum, which in medieval times would evolve into the guilds of craftsmen or guilds of free masons (free-masons), until the birth of speculative freemasonry in the 18th century. With a patient gaze, we can observe a golden thread that weaves many pearls of knowledge to be passed on, as in a necklace that starts in archaic times and arrives to the present day.

The same path of knowledge is unveiled by highlighting the radix Davidis, the lineage of David, the brotherhood so extolled by Abbot Joachim da Fiore, born from the lineage of Judah, son of Jacob, who later moved to Europe. This confraternity, which later became known as ‘Fidelis in Amore’ (Faithful in Love), of which Dante Alighieri is said to have been a follower, later merged into the confraternity called the ‘Jordanites’, led by the great philosopher from Nola, Giordano Bruno. According to Frances Yates, an expert on Renaissance hermeticism, after Bruno’s death, the ideas of the Jordanites may have provided the impetus for the formation of the Rosicrucian movement, which is still shrouded in many mysteries and interesting theories.

Bringing order to the tangled skein of the world is an ambitious, incredible, perhaps almost naive task. And if most get lost in this attempt, the great artists succeed surprisingly well, leaving behind a mark that is destined to last forever.

Ettore Roesler Franz certainly succeeded in his endeavour, because in addition to being an artist, he was a complex, extraordinary and deeply human man, just as can be seen in his works, and it is through clear, sincere eyes that we understand all the fascination of initiatory esotericism and enter with passion and curiosity into an esoteric journey into the purest art.

Ettore Roesler Franz was unique among 19th century Roman painters, not least because he was not only privy to the secrets of the initiates, but also had a network of friendships with Europe’s leading artistic and cultural figures. This is confirmed and evident both by his long stays abroad and by the astonishing number of exhibitions he staged throughout Europe. With Ettore Roesler Franz, we discover the importance of symbolism and are about to be reborn to new life thanks to the messages concealed in his works.

And if the artist is so great, the writer, my friend Franz, gives us with his words an equally important and profound testimony, because when we have finished reading, we will no longer be able to look at a painting with the same eyes: all our senses will be on the alert and our attention stimulated as never before. We will understand that every work opens the door to complex narratives and that the eyes of an artist are endowed with a poetry that we should never underestimate.

Through the reading of this book we learn that the series of 120 watercolours of ‘Roma Sparita’ painted by Ettore Roesler Franz, owned by the City of Rome, conceal a profound esoteric meaning, where the many threads hidden in these beautiful paintings intertwine, not only with Ettore’s life, but with the history of the Roesler Franz family, forming the fabric of this fictional saga, the plots of which I do not pretend to summarise in this foreword, nor do I wish to deprive the reader of the pleasure of reading, a pleasure that will be expressed to the fullest when one comes to the conclusions.

PART I

Friedlant

An icy wind blew across the valley as the sun, fading from the setting sun, hid behind the mountains. A dragnet of horsemen, under a sky of dark clouds, crossed a deep gorge. Snow skirted the edges of the path on that evening of 20 November 1746. The soldiers were galloping on their steeds, singing war hymns. They were returning from a sortie into the enemy camp that had yielded rich spoils. A few more hours separated them from their homes, sheltered by the mighty walls of their fortress, when they would finally be warm in front of blazing fireplaces, embraced by their women, who, after satiating them with copious portions of barbecued pork and mugs overflowing with beer, would then offer their bodies to their warriors for a night of unbridled sexual pleasure.

Years had already passed since the outbreak of yet another war that bloodied a vast border area between the Habsburg Empire, Poland, Prussia and Saxony: as a pretext for fighting each other, the states had been using the investiture of Maria Theresa to the throne of Empress of the Habsburg Empire for six years.

That evening in the mercenary troop led by commander Karl, there were two young brothers, Franz and Vincent Rösler, who in their hearts would have preferred a less adventurous life, but fate had been cruel.

Six years earlier, on a tragic night, they had lost not only their beloved father Manfred and uncle Friedrich, but also their older brother Joseph, their only sister Beatrice and their beautiful mother Constance, killed after being barbarously raped. Franz had saved himself because he had managed to hide behind the large curtain of the living room, only managing to escape when the goons, after having drunk litres of beer, had finally fallen asleep. The boy running in a few minutes had reached the annexe where his only surviving family member was sleeping, his younger brother Vincent, who, after waking him up and warning him of the danger, helped him dress quickly.

The manor where they lived was in the vicinity of a dense forest, which they reached by running at breakneck speed in the darkness of a moonless night. They did not stop for at least a couple of kilometres, when they finally reached Hans’ hut. Franz, although very excited and out of breath, managed to explain in a few minutes what had happened. The three friends decided, by mutual agreement, to leave the next morning, moving away from the too dangerous area. The two Rösler brothers, too agitated and frightened, could not fall asleep: Hans offered them his leather flask containing Polish vodka. The alcohol got the better of them and after half an hour they fell asleep. On 24 June, his name day, Hans woke up at first light and after a short prayer to God, he ordered his shepherd dogs to herd the flock. The noises of the animals and the light of the sun woke the two Rösler brothers, who, after eating a few slices of bread and cheese, drinking some sheep’s milk and filling their flasks for the journey at a nearby spring, set off next to Hans in front of the flock.

They made their way to what is now the eastern border of the Czech Republic with Poland, in the far east of North Bohemia, where the spectacular Kekonose, the Giant Mountains, rise in the distance. This range (in which Mount Snezka, the highest in Bohemia, rises to 1602 metres) is now the territory of a beautiful nature reserve.

The three fugitives chose to head for the hilly area of the Iser Mountains, where they arrived at a plateau with a large meadow of thick grass, situated on the slopes of a forest, furrowed by a stream, from which cold clear spring water gushed, and they realised that this place would be perfect for building a wooden hut lined with animal skins to spend the rest of the summer there.

It was an ideal place: the forest provided the wood for the fire, the stream the water for drinking, the earth the fodder for the herd and the fresh air the ideal climate for spending the summer months.

During that time they fed on the meat of the flock’s lambs and wild rabbits, which Hans caught with his traps. The shepherd was also very good at making fresh cheese from the milk of the sheep he milked every morning. The two Rösler brothers, on the other hand, took charge of picking berries in the brambles and apples by climbing trees. In the evenings, after dinner, sitting around the fire, Hans played the pipe, while Franz and Vincent sang merry songs. Every night, before going to sleep, the two Rösler brothers raised their eyes to heaven, reciting the Pater Noster, as their beloved mother Constance had taught them from an early age, and with sad thoughts turned to their dead, they fell asleep in the little hut. Before falling asleep, Hans often placed sheep skins on the little bodies of the two children to shelter them from the bitter cold of the night.

At the end of summer with the arrival of the first autumn cold, the three youngsters decided to return to the valley. On the morning of 6 October 1736, they arrived in the heart of the hills at Lazne Libverda, whose thermal baths have been visited by visitors for centuries. As soon as they reached the outskirts of this town, they saw in the distance the manor house where, until a few months before, they had lived happily with the rest of their loved ones and which, instead, was now occupied by the murderer of their parents, who lived there together with his family and his henchmen, whom he used as assassins.

Franz and Vincent realised in those moments that the time of regrets and childhood was over, the happiness of yesteryear would never return and it was useless to live with illusions. If they wanted to move forward, they had to forget the past, be projected into the future, hoping that luck or fate would turn the wheel in a positive direction.

They entered the small village church, while Hans led the sheep to a clearing near the village house.

Franz and Vincent recognised the parish priest Ludwig and embraced him, then all three knelt in a pew and prayed begging for divine help. Both brothers had great faith in God and above all they sensed that by trusting in Him, He would always help them through difficulties. Shortly afterwards, they went out and returned to their shepherd friend to help him sell the lambs.

When Hans saw them, he gestured to them with his hands, instructing them not to approach him, but rather to get out of the village house as soon as possible and start walking towards the nearest town. Their friend rightly feared that the murderer of his parents also wanted their heads, eliminating two inconvenient witnesses. The shepherd sold fifteen lambs and eight wheels of goat cheese and then joined his two friends with the flock.

They arrived in Liberec, famous for its town hall built in the Flemish neo-Gothic style, having been founded in the Middle Ages by Belgian linen weavers. It was about half past midday, so they stopped at an inn where they ate game skewers with roast potatoes, washed down with large mugs of beer, which they had not drunk in months. After lunch they continued northwards and by dusk they arrived happy but exhausted at Frydlant, where the imposing castle stands. The building stands on a wooded rocky peak on the edge of the town overlooking the river Smeda. The castle blends architectural elements from different eras: the medieval walls and cylindrical tower date from the 13th century and blend in with the rest of the Renaissance and Neo-Gothic buildings.

The boys were astonished by the grandeur of this fortress, which they had never seen, but of which they had heard so much from their father Manfred, who in the company of their uncle Frederich often travelled there. The three of them were very tired from the journey and after a frugal meal of bread and cheese, they fell asleep in a meadow close to the blockhouse. When they were still half asleep at first light, Karl, the deputy head of the garrison, arrived. Franz, hearing noises, woke up immediately and recognising him, because he was a friend of his father Manfred, got up and ran to him to hug him, all transfixed, telling him about the sad events of the last few months.

Frydlant Castle

Karl reluctantly replied: “The murderer of your parents is the brother of the bishop of Liberec and therefore, however evil he may be, he is to be considered untouchable. Then he continued in a reassuring tone: “By now you Franz are fourteen years old and your father told me that since you were a child you have been riding horses very well and above all you already know the rudiments of fencing. You too, Vincent, who should be about ten years old, already ride. Do you want to become knights?”

Franz looked at Vincent, their eyes met and they immediately realised what they were supposed to do by immediately accepting the offer.

The duke Albrecht von Wallestein

So many years had passed, Karl had proved himself not only a good commander but above all an excellent father, loving the two Rösler brothers as if they were his own sons. He was proud of his two boys to whom he had taught all the secrets of the art of war. Franz was now 25 years old and Vincent 21. Their putative father wished in his heart that his two boys had settled down as soon as possible with so many brats around the house, dreaming that he would also train them in the craft of arms.

In spite of the life-threatening danger that hung over all those populations due to wars of indescribable cruelty, in which one risked losing everything every day, and above all of interminable length as the duration of years, or who knows, perhaps it was precisely for these reasons of having to gamble one’s life risking death every day, that induced Karl to look to the future with hope. He wished that this terrible war would soon come to an end, but no matter how absurd it was, he knew no other way to live than to have to fight. There was, in fact, no other way of living, or perhaps it would be more appropriate to call it surviving, in those times and territories. In fact, since he was a child, he had been brought up with the teachings of always being ready to fight like his father and like all his ancestors from the time of the Protestant Reformation, which was followed by the Catholic Counter-Reformation, with effects that were devastating on the life of the population.

Since 1740 when this last war had broken out, Karl, Franz and Vincent had overcome so many dangers and so many adventures: they hardly ever thought about the past, but only ever dreamt of the future, just as they never thought about their victims and the atrocities they were forced to commit in order to survive, having only the law of the strongest in mind. Also that evening, all three of them had spent yet another military mission together with a squad of knights, and they were looking forward to returning safely within the high, thick walls of their fortress at Frydlant.

Franz, however, felt strange. Since the night he had witnessed the death of almost all his family members, he had sharpened his sensitivity, developing over time a special intuition, a sixth sense, that allowed him to perceive sensations unknown to others. That evening of 10 December 1746, the elder of the two Rösler brothers sensed that fate was not on their side. However, he did not know how he could share his feelings with Karl, to whom he was very close, for fear that he might appear to be a coward, and so he preferred not to confide in anyone, including his brother Vincent, keeping his premonitions to himself.

The garrison followed the usual path and entered a section of dense bush. Suddenly from both sides of the road came a wave of bullets that struck half of the horsemen in the troop. Karl, who as usual was in the lead, was hit by bullets from both sides in the chest and fell from his steed. Franz realised that there was nothing more he could do to help either their beloved second father or the other comrades who had fallen from their horses, so he shouted to Vincent, who had also miraculously escaped the ambush:’ Speed up the pace and let’s escape from this place of death’.

Arriving at Frydlant Castle when they raised the alarm they realised the many casualties they had suffered in the ambush. Vincent was distraught when he noticed that Ludwig, his best friend, was also missing.

Franz reported what had happened to the commander of the castle, but the general chose to be cautious and did not want to risk a sortie that night, to recover the wounded and prisoners, which could have proved disastrous.

At dawn the next day, a squad of horsemen followed by two chariots went out to recover the bodies of the fallen, and then gave them military honours and burial in the cemetery. For five of their comrades, their bodies were not found and they guessed that they had been taken prisoner.

For the dead, the general wanted the funeral to be held in St. Anne’s Chapel inside Frydlant Castle on the same afternoon. It was a religious ceremony attended by all the inhabitants of the fortress. The widows with their children were in despair and the screams and cries of grief lasted throughout the night. Franz and Vincent were anguished: for the second time in their short lives, the world had collapsed on them. That night, they both swore to themselves that as soon as their time would allow, they would abandon military life and emigrate, unable to continue living in a land that had been tormented for too long by endless wars and violence of all kinds.

Days passed, but since Karl’s death, the two Rösler brothers could no longer integrate with their comrades-in-arms and preferred not to attend the knights’ hall of the castle. Having lost their parents and all material possessions as children and now their putative father was too great a pain for both of them. Memories slowly began to resurface. Some ten years had passed since the day the two brothers had met Karl on their way and Franz and Vincent had grown tall, strong and above all well versed in both the art of war and hand-to-hand combat. They never asked too many questions or had too many scruples, life had been merciless with them and so their hearts had hardened like marble. They had both chosen, as their own motto, a dry but merciless Latin saying, learned from a former seminarian monk who had become a mercenary like them, ‘Mors tua, vita mea’, a lapidary phrase that did not give way to too many discounts towards their enemy.

Franz could no longer sleep, his grief distressed him and memories nagged at him: that night he remembered when Karl, four years earlier, had lost his wife Elisabeth during the delivery of their first child, who had also died, and feeling too lonely, sad and grief-stricken, had asked the two boys if they would like to go and live in his house, rather than sleeping in the garrison dormitory. From that day on, the two brothers finally had the affection of a father again. Karl was proud of his boys and in addition to teaching them all the secrets of the art of war one evening after dinner while they were tasting a delicious Polish vodka, the spoils of war, he wanted to tell them about the life and exploits of the man who was considered the most important general and military strategist who lived in their lands: “My dear children, you should know that on 23 May 1628 in a popular uprising in Prague three court officers were thrown from the windows of the Castle, who emerged unharmed but humiliated, the act is remembered as the Second Defenestration. It was the signal for the beginning of the Thirty Years War. Protestant forces took up arms against the Habsburgs initially scoring a number of victories, but then Catholic forces gained the upper hand and Emperor Ferdinand of Habsburg returned to Prague in triumph. Thirty thousand Protestant families fled as the Counter-Reformation became more and more vigorous. Their lands partly passed to Ferdinand’s loyalists, including the commander of the imperial troops, Albrecht von Wallestein. The latter, however, with his overly brilliant military successes also sowed the seeds of his downfall because they appeared in the eyes of the emperor as a real threat. In fact, for a few decades much of northern Bohemia was run by Wallestein as an independent state. Of noble origins, he was born a Protestant in East Bohemia in 1583. In 1606 he converted to Catholicism and in 1617 after a military campaign against Venice, Emperor Ferdinand II invested him with the title of Duke. Wallestein became rich and his wealth grew thanks to his marriage to the wealthy Isabella von Harrach. In 1620 after the Battle of White Mountain he obtained the towns of Frydlant and Jiin, expropriated from the Protestant nobles, and thus became the owner of 24 fiefs and castles, including the enormous fortress of Mala Strana.

Albrecht Von Wallestein, duke of Frydlant

The emperor grateful for his services appointed Wallestein duke of Frydlant in 1625. As his property also included mines, the duke became even richer and, above all, more powerful. By placing his troops at the disposal of Ferdinand II as a mercenary, he made himself indispensable to the emperor and was appointed Supreme Commander of the imperial forces in 1625. Political pressure against the general led to his resignation in 1630, but two years later he resumed general command. He soon gained the emperor’s trust again by defeating and killing Gustavus Adolphus II of Sweden at the Battle of Lutzen in November 1632. Unfortunately for the Duke of Frydlant, the Emperor felt increasingly threatened by the independence of his loyal commander and his negotiations with the Swedes, making Ferdinand of Habsburg increasingly uneasy. When Wallestein asked his officers to swear allegiance to him, the emperor accused him of treason and ordered him to be captured. Three days later the duke and three of his officers were murdered by soldiers loyal to the emperor. His properties were divided up and the Duchy of Frydlant ceased to exist. Dear Franz and Vincent, your family, who were loyal to Wallestein, also fell into ruin with him. Your great-grandfather Manfred paid with his life and many goods were confiscated from him. Your grandfather, whose name was Franz, went to live in that small manor, where you also grew up.

Karl interrupted himself and after a sip of beer asked the two boys if they were tired, both of them intrigued by these events asked him to continue: “The continuous Swedish invasions of Bohemia and Moravia caused enormous devastation, not even Prague was immune. The Thirty Years’ War dragged on causing indescribable misery until the Peace of Westphalia was negotiated in 1648. In 1637 Ferdinand III succeeded to the throne. He imposed on the Bohemians who had sided with the Swedes that they would no longer be allowed to return to the country and the Habsburgs began to burden the peasants with heavy taxes. The outbreak of the plague swept through cities already devastated by war, bringing further suffering to the population. Returning to the events in our town at the end of the Thirty Years’ War, Frydlant Castle was owned by the Swedes, who strengthened its defensive walls. In 1639, Christoph von Redern returned here after a period of exile. A year later, the Swedes completely abandoned Bohemia and this resulted in the loss of religious freedom and Protestants were forced to adopt the Catholic religion, many went into exile and never returned to this area, which continued to suffer until 1642. Later the castle passed to Matthias Gallas, Duke of Lucera, who died five years later in 1647 and since then the castle has been owned by his descendants as you also know’.

Franz also remembered that evening when Karl, having finished his narration, invited the two brothers to go to bed and then, after blowing out the candles, left the house to go to Ingrid, one of the castle garrison’s cooks, to sleep. Franz with his thoughts turned to her, to whom he was very fond and whom he had seen destroyed in church on the day of Karl’s funeral, finally managed to fall asleep.

The Church of the Holy Cross in Frydlant

The commander of the castle reassured Franz and Vincent that they would continue to live in Karl’s house, even after his death, and the two boys were enormously happy about this because they wished to remain far away from their comrades-in-arms, as they were beginning to feel different from all the other soldiers and could no longer integrate with them as before. When they went to pray, the two Rösler brothers preferred instead of the St. Anne’s Chapel inside the castle, the Church of the Holy Cross, located in the centre of the small town of Frydlant, where they soon became friends with the parish priest Joseph, who took them under his benevolent protection. Initially, the change of church was due to the need to get away, if only for a few hours, from the castle and the military environment. The parish priest was a kind and jovial person who explained: “I knew your father Manfred and you are always welcome. This church is quite recent, not yet two hundred years old, it was built by Italian architects in the mid-sixteenth century in a mixture of architectural styles, and inside it the Redern family had a mausoleum built in 1610 as a tomb for their family members’.

After the vesper services, the priest would often converse with the two brothers about Jesus Christ and the Bible, but in a different and totally unconventional way from how they had heard about it up to that point. In his speeches, the parish priest used only words of love and peace, unlike the way religion was regarded in their military garrison in the castle, seen only as an excuse to kill each other in fights that had nothing Christian about them and in which the only aim was to sow hatred and violence, useful and necessary only to plunder the riches of the enemy.

Joseph went further one evening, and opened up completely with the two young men, explaining that he did not share and absolutely did not understand the reason for those religious wars between Catholics and Protestants, in which Jews were also persecuted, because all men are brothers. The priest particularly liked the Franciscan thought of giving peace and helping one’s neighbour.

Franz and Vincent were both thunderstruck to hear these words. The two young men began to attend the church of Santa Croce assiduously, where they attended late afternoons, when they were free from military commitments, both vespers and mass. One afternoon they entered the church before the usual time and found the nuns and parishioners praying the rosary. Franz and Vincent knelt down and joined in reciting that prayer, which in time helped them to rise to God. From that day on, they sought, as far as was possible for two soldiers, living in a military environment inside a castle during a time of war, to detach themselves spiritually from the earthly world.

Church of the Holy Cross

After a couple of months one evening in the late winter of 1747, Franz and Vincent were invited by Father Joseph to stay for dinner in the rectory, the adjoining house next to the parish priest’s church, where two nuns had prepared some tasty food. They started dinner with a hot mixed vegetable soup, which was followed by a tasty goulash with potatoes. From that evening on, the dinners with the parish priest became more frequent, and as the friendship grew closer, Father Joseph began to invite them to Sunday lunch after church services, where they were served various kinds of cold meats accompanied by rye bread baked the day before, smoked fish as a main course, and light beer as a drink.

On Sundays after lunch, Father Joseph entertained them with stories from the Bible, which the two boys were very interested in learning about, especially those about the lives of Moses, David and his son Solomon. While listening to the pastor, Franz and Vincent often enjoyed a small glass of fine Polish vodka.

One Sunday, Joseph addressed them: ‘Since you are very devoted to the rosary, you should know that centuries ago, the Psalms from the Holy Bible were recited in monasteries during this prayer. In the late Middle Ages, an Irish monk suggested that the Lord’s Prayer be prayed instead of the Psalms. Soon this prayer began to be recited outside religious centres. To count the prayers, the faithful used various methods including strings with 50 knots. Then, as a repetitive form, a new form of prayer was developed in the 13th century by Cistercian monks, which they called the ‘rosary’ because they compared it to a crown of mystical roses given to the Virgin Mary, the rose being in fact the Marian flower par excellence. A monk of the Carthusian monastery of Cologne, Henry Kalkar, around the middle of the 14th century, included in every dozen Hail Marys also the recitation of an Our Father. It is very nice that you appreciate so much the recitation of the rosary prayer, which means ‘Crown of Roses’ in which we meditate on the mysteries of the joy, sorrow and glory of Jesus and Mary. The rosary is a powerful weapon against evil to bring us true serenity”.

When the two Rösler brothers heard these words, they both felt a thrill that confirmed their desire to live in a context of peace as they were no longer able to cope with battles and war. In German, the word rosary is spelled rosen kranz, and Father Joseph became more and more enthusiastic about Franz and Vincent when he saw them enter the church, exclaiming: “Here are my two dear parishioners rosen kranz”, and both brothers liked that nickname.

Holy Cross Church in Frydlant

On Easter Sunday, 2 April 1747, after an apprenticeship of several months, Father Joseph wanted the two brothers to help him serve Mass, and they were very enthusiastic about this. On the feast day of St George, 23 April 1747, Mass was held in the Castle, in the open air, outside the chapel of St Anne. A temporary wooden altar had been built where Father Joseph and Father Heinz, the castle chaplain, concelebrated together. At the end, the Blessed Sacrament was exposed, so that God would protect all the soldiers. The religious service was favoured by the summer weather and the optimistic mood of all present, who were beginning to sense the end of the long war that had begun seven years earlier. Although there was still the occasional skirmish in the surrounding territories, news was circulating that negotiations were underway in major European capitals between the ambassadors of the belligerent countries: everyone was exhausted by the war, especially the civilians affected by grief and misery, but peace was finally beginning to be felt in the air.

Father Joseph had sensed that the two boys were different from the other inhabitants, because they were eager to learn new things and, above all, they were eager to go away and leave those sad places. So he, who had been in seminary in Prague, wanted to tell them about the wonders of this city and its cultural grandeur one evening at dinner. Franz and Vincent were as if dazzled by these words in which he called this city one of the three, together with Lyon and Turin, that form the white magic triangle in Europe. The two Rösler brothers looked each other in the eye as Father Joseph narrated, and guessed that as soon as the war was over they would leave Frydlant, where too many sad memories haunted them, to visit the Bohemian capital.

Rudolf II

The war drew to an end and Father Joseph on the evening of the day when peace was announced, he had the bells of the Church of the Holy Cross festively rung and the Te deum was sung at the end of mass to thank God that such a catastrophic event, which had bloodied Europe for so long, had finally come to an end. The priest was particularly happy and had the nuns prepare a hearty dinner with hors d’oeuvres of smoked fish and cold meats, mixed roasts with barbecued vegetables and a cake. Father Joseph had also invited the Burgomaster of Frydlant who, at the end of the meal at Franz and Vincent’s request, began to narrate: ‘Slightly more than seventy miles is the distance that separates our city from Prague, which during the Renaissance Rudolph II of Habsburg made one of the most refined, rich and renowned capitals of the European continent. He summoned European intellectuals, alchemists and artists from whom he commissioned more than four thousand works of art for his collections. In 1583, the Austrian emperor responded to the Turkish threat on Vienna by moving the imperial capital to Prague. Rudolf II was an introverted, fragile and melancholic person and was prone to bouts of depression.

Rudolf, overcoming sectarian differences between Catholics and Protestants, signed the ‘Letter of Majesty’ in July 1609, which allowed total religious freedom to the people of Bohemia.

Such a level of tolerance was unprecedented in the rest of Europe. But his behaviour could not be endorsed by the rest of his family and in 1611 he was forced to abdicate. In the years of his reign, Rudolf did extraordinary things for our capital city. Thanks to Rudolf II, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Dominus Mundi, King of Bohemia, Hungary, Germany and the Romans, at the end of the European Renaissance there was an incredible and unparalleled meeting of minds in Prague. The seat of his power was the Castle, at the centre of Bohemia, at the centre of Europe, at the centre of the known world.

Rudolph was obsessed with alchemy, which in Renaissance Europe merged with astrology, astronomy, medicine, into a proto-science that the emperor fully embraced in his quest for a uniqueness that would help him understand the universe, and he hired the English alchemists Edward Kelley and John Dee at his court, making Prague the largest centre for the study of astronomy and astrology in Europe.

But it was not political influence that Rudolf sought; he was already the most powerful man in Christendom. Rather, he desired power over nature and power over life and death.

Like Marlowe’s Faust, he was ready to risk his soul in the all-encompassing quest to understand the deepest secrets of nature and the enigma of existence. Inspired, like Hamlet, by the new humanistic knowledge Rudolf II questioned the old certainties by seeing the two sides of any coin at the same time, he then found it difficult to decide and act”.

The burgomaster interrupted, it was getting late and he had to say goodbye, but since Franz and Vincent were so interested in his story he would finish it at his home a few evenings later, if they agreed to be invited along with Father Joseph.

All three accepted happily and gave thanks.

A few days later at the end of the evening religious services at the stroke of 8 p.m., announced by the big clock on the tower in Frydlant’s central square, they pulled the rope of the bell on the door of the burgomaster’s house. The doorman opened it and they entered the palace.

Before dinner, the landlord announced that the meal would be quite frugal, having had his lands burnt by his Protestant enemies and so the harvests had been very poor for the past three years. The two young men were not interested in eating, in the barracks at the castle food, the fruit of the soldiers’ constant raids, was never lacking on their table, as much as they were driven by curiosity to learn knowledge and knowledge.

The burgomaster’s wife and daughters, together with his only son, dined secluded in a small sitting room near the kitchen, while the master of the house and his three guests sat around the table in the great hall, where precious Flemish tapestries hung on the walls, interspersed with two hunting trophies: a pair of antlers from a stag and a stuffed head of a boar.

After an auspicious toast for lasting peace, they began to eat.

The burgomaster had had a special dinner prepared for his guests, albeit frugally due to the constraints of war. Pheasant eggs and smoked ham were served as starters. As starters, potato dumplings were served sliced and placed on a large stick and dipped in different full-bodied sauces, placed in bowls in the centre of the table. For main courses, the waitresses brought a large duck accompanied by a mixture of pickled vegetables consisting of cabbage, beets, carrots and lettuce. Finally, for dessert, fruit dumplings filled with plums, apricots, strawberries and blackberries. All this was always accompanied by mugs of beer, which were filled from large barrels in the kitchen by Hubert, the palace apprentice.

As Franz was eating, he began to think that if that was a frugal dinner, he wouldn’t mind living in that magnificent house at all!

When dinner was over, the burgomaster had his pipe brought to him, made in Austria some twenty years earlier, about fifty centimetres long, made of hand-decorated porcelain, in which his family’s noble coat of arms had been painted on both sides. After loading the cooker with an aromatic tobacco from New World plantations given to him by a Saxon prince, his close friend, he lit it with a long wick.

The landlord began to take a few deep puffs, which filled the air with a fine scent with a slightly smoky flavour within moments. After a cough, he paused to catch his breath and to enjoy a small glass of pear brandy produced on his hillside property.

After this ritual lasted about ten minutes in which Father Joseph, Franz and Vincent watched in strict silence, the burgomaster resumed the narration he had interrupted a few nights earlier at the parish priest’s house: ‘As emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Rudolf II was responsible for maintaining the power of the Catholic Church. But by tolerating Protestants and Jews and encouraging freedom of thought and expression, he was unable to avoid a clash with the forces of the Inquisition and the Counter-Reformation, who wanted total control over thought and knowledge. Anyone who crossed the boundaries drawn by the Vatican was accused of having links with the devil. In the eyes of the Inquisition, the unrestrained pursuit of truth did not lead to enlightenment so much as damnation. Nevertheless, Rudolf II dared to defy the dictates of the Church and thus earned an important and interesting place in the cultural history of the Renaissance. His generous patronage of alchemists, physicians and astrologers throughout Europe inadvertently laid the foundation for the scientific revolution of the 17th century. In his mystical aspirations, in his obsession with occult knowledge, in his incessant search for truth, one can find the first glimmers of modern philosophy and science. Making no distinction between the world of arts and ideas and everyday life, Rudolf invited painters, sculptors and enlightened artists from all over the continent to his magical theatre, which made Prague the cultural capital of Europe. The emperor had close relations with the Jewish community. The Habsburgs had been accommodating the Jews for a long time, by virtue of their skill and intellectual knowledge. Jews had been coming to Prague since the 10th century. Their neighbourhood, with its vast cemetery, was located on the right bank of the Moldova. During the reign of Rudolf some ten thousand Jews lived in our capital, forming the largest community of the diaspora. Not only was the city called the Mother of Israel, but in those years that saw the great flowering of Ashkenazi culture, it became known as the ‘Golden Age’ of Jewish history. The large Jewish community in Prague, in comparison to those in other European capitals, enjoyed considerable privileges and among its citizens were some of the richest people in the city.

For further input into his studies of the occult and Kabbalah, Rudolf II summoned the Chief Rabbi of Bohemia, Judah Low, a friend of the physician and alchemist Michael Maier, the most original mind in the city’s Jewish community, an eminent Renaissance scholar as well as a Kabbalist.

If Neo-Platonism, Hermeticism, Kabbalah and magic were the essential elements of the worldview of Rudolf’s court, alchemy and astrology were the main sciences and shared the same perspective. Prague became the capital of the followers of Paracelsus, the founding father of iatrochemistry and pharmacy, and the forerunner of homeopathic medicine. Rudolf II welcomed the greatest thinkers and scientists of the time. These included the English magician John Dee, the German alchemist Oswald Croll, the Polish alchemist Michael Sendivogius, the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and the German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler. Due to the constant threat of persecution by church and state, these original and subversive thinkers were often forced to travel around Europe in search of a congenial place where they could continue their pioneering and potentially heretical work.

Astronomy and astrology had not yet taken separate paths: elements of the former were used to understand the mind of God and calculate the Church’s calendar, while the latter was important in predicting the future, both with regard to climate and harvest, and the fate of individuals and nations. In an uncertain world, anyone who claimed to be able to read the future was taken seriously, especially by Rudolph II.

Among the various illustrious figures at Rudolf’s court was the astrologer Johannes Kepler. Rudolf’s Prague was the main centre of culture and scientific discoveries in late Renaissance Europe’.

When the narration was finished, the burgomaster called his wife, who arrived accompanied by a waitress holding a jam tart with wild berries, which she placed on the table, while another waitress took from the larder some glasses and a precious Bohemian crystal carafe containing Becherovka, a liqueur with a secret recipe resulting from the fusion of some twenty different herbs produced by a well-known Prague alchemist.

The burgomaster was particularly happy that evening. After inviting his wife to sit at the table with him and after taking three consecutive long puffs of smoke from his long pipe, he continued the narration: ‘Having illustrated the figure of a ruler so beloved by us Bohemians as Emperor Rudolf II, I now also want to mention Albrecht von Wallestein, the duke of Frydlant, who in life was a close friend of your great-grandfather Manfred. In 1623, the duke began work on the construction of his huge palace in Prague, which was named after him. Throughout his life he was obsessed with astrology: Kepler created several horoscopes for him. To satisfy this passion, the duke had an astronomical and astrological corridor built to connect the north and south wings of his palace in the Bohemian capital. The vault, representing a celestial sphere while the walls stand for the world, is divided into seven parts corresponding to the number of known planets. On the walls, the twelve signs of the zodiac are represented in association with the planets in the form of allegories. Far from being merely decorative, this cycle of frescoes has a real meaning according to the theory of Hermes Trismegistus, according to which what is at the top is like what is at the bottom, allowing celestial energy to be drawn more strongly into the room in which the fresco is located.

Despite pressure from Wallestein, John Kepler refused to make predictions for the period after 1634 as the stars were unfavourable to his patron. Everything came true and the duke was assassinated in 1634’.

The burgomaster was moved by these words; memories had resurfaced of when, as a child, he had learned of the duke’s inauspicious fate from his grandfather. Then he resumed: ‘Boys, I heard from Joseph that you want to leave this land of ours, and the advice I can give you is to emigrate. This is a land that has been bloodied by fratricidal strife for too long. I have lost many Protestant and Jewish friends who were forced to leave their homes in order to continue to profess their religion. There is no peace here’. The wife clutched at her husband’s side to hearten him as Pastor Joseph said goodbye together with the two boys, who, after hearing those sad last words, were more and more eager to flee that tormented land.

Prague

A couple of days later, on 17 May 1747, Franz and Vincent went to the Church of the Holy Cross in time to attend the prayer of Lauds, which was followed by the rosary and immediately afterwards by Mass. When the faithful came out Joseph asked Franz to bar the door and led them into the sacristy. The two boys confirmed their decision to leave. The parish priest sat down at his desk and taking a sheet of lamb’s parchment and a goose feather, which he dipped into the inkwell of black ink, he wrote a long letter, which he folded without reading its contents to the two brothers. Then he heated some scarlet-red lacquer wax, which after melting, he poured some on the envelope, affixing his own seal. On the other side of the letter he wrote an address in Prague, where the two boys were to deliver it.