15,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

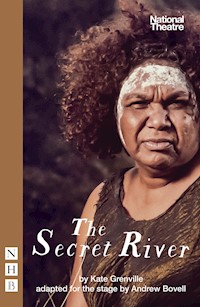

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

William Thornhill arrives in New South Wales a convict from the slums of London. Upon earning his pardon he discovers that this new world offers something he didn't dare dream of: a place to call his own. But as he plants a crop and lays claim to the soil on the banks of the Hawkesbury River, he finds that this land is not his to take. Its ancient custodians are the Dharug people. A deeply moving and unflinching journey into Australia's dark history, Andrew Bovell's adaptation of Kate Grenville's acclaimed novel The Secret River was first performed by the Sydney Theatre Company in 2013. The play had its UK premiere in August 2019, as part of the Edinburgh International Festival, before transferring to the National Theatre, London. This edition includes an introduction by adapter Andrew Bovell, a foreword by historian Henry Reynolds, and music used in the original production. 'The Secret River is a sad book, beautifully written and, at times, almost unbearable with the weight of loss, competing distresses and the impossibility of making amends' Observer on the novel The Secret River

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

THE SECRET RIVER

by

Kate Grenville

adapted for the stage by

Andrew Bovell

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Foreword by Henry Reynolds

Introduction by Andrew Bovell

Production Details

Acknowledgements

The Secret River

Prologue

Act One

Act Two

Epilogue

Music

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Foreword

Henry Reynolds

It was while walking over Sydney Harbour Bridge that Kate Grenville experienced the epiphany which led to the writing of her novel The Secret River. She took part in the great procession for reconciliation on Sunday, 28 May 2000. She caught the eye of a young Aboriginal woman who was watching the marchers file past. They exchanged smiles. At the time Kate was thinking about her ancestor, Solomon Wiseman, about whom there was a living tradition of oral history and which took her family’s historical memory back to the first generation of European settlement. She wondered if Wiseman had ever known the ancestors of the Aboriginal woman. What seemed even more significant was that the fleeting encounter took place directly above the likely location of Wiseman’s disembarkation from the convict transport in 1806.

Family history and the national desire for reconciliation met and merged. Both propelled Grenville into a period of intense research into the history of early New South Wales. On the one hand she came to appreciate the profound importance of the indigenous history which continued to run beside the well-known stories of white pioneers. An even more profound realisation was that when Solomon Wiseman ‘took up land’ on the Hawkesbury River, he had actually taken land from the traditional owners; that the family’s early opulence was based on expropriation. And that it was most likely effected at some time by indiscriminate violence perpetrated either by Wiseman himself or by friends and associates. Grenville’s experience mirrored that of Judith Wright a generation earlier. Wright had set out to write an account of her pioneering ancestors. As she proceeded she discovered how family members had moved north from New England and been involved in the violent settlement in central Queensland. Both poet and novelist were profoundly shaken by the unexpected turn in family history and their discovery of the long-hidden history of violence.

It took Grenville five years of research and twenty drafts before the book was published. It was dedicated to ‘the Aboriginal people of Australia: present, past and future’. Controversy swirled around her soon after it was launched in 2005: debate about fiction and history, intense at the time, distracted attention from the real significance of the work. But it did not deter readers. The book was reprinted ten times in two years. It sold over 100,000 copies and was subsequently translated into twenty languages. It won prizes both in Australia and overseas. Clearly The Secret River was a book for the times. Readers were avid for its message.

The same appears to be the case with Andrew Bovell’s stage play adapted from the novel. It was the first work commissioned by Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett for the Sydney Theatre Company in 2006, soon after the initial publication. The time lag between novel and play has not diminished the power of the story. Capacity audiences in Sydney, Canberra and Perth in March 2013 gave the players standing ovations – sometimes after moments of stunned silence. Many people cried. Few were untouched. The West Australian observed how the river ran deep for the Perth audiences. Critics in Sydney declared that a classic of Australian theatre had appeared.

The success of the play can be credited to the actors, the production team, and especially to the celebrated director Neil Armfield. But underpinning all their creative endeavour was Bovell’s brilliant adaptation of the novel. His work was certainly facilitated by Grenville’s willingness to stay at arm’s length, requesting only that the script writing result in a good play. But even with the novelist’s detached cooperation the task was challenging.

Novels and plays share some things in common. They characteristically adopt a narrative structure and unfold stories through time. At their best they create characters whose personalities and passions drive the action forward. But the differences between the two genres are greater than the things they share. A novelist can use an abundance of words. Grenville unfolds her story over 330 pages in well over 100,000 words. She is able to provide almost endless detail about people and places and material objects. She can reveal her characters with a slow accretion of knowledge and insight in the way we get to know people in real life. So like anyone adapting a novel for the stage Bovell had to whittle the story down in time and place while maintaining the cast of principal characters and elucidating the most significant themes. He had to abridge rather than adapt, preserving the essence of the novel and those events and the dialogue which made it significant in the first place.

The 330-page novel was pared down in both time and space. The first two sections, set in London and Sydney, are jettisoned while providing Bovell with a past allowing retrospective allusions that enrich the dialogue and give added depth to the main European characters, William and Sal Thornhill. All the events take place on the banks of the Hawkesbury River over a seven-month period in 1813 and 1814. The central focus is on a forty-hectare patch of cleared land where Thornhill has decided to start farming with his wife and two boys. At one level it is a classic story of pioneering, of the hardships and vicissitudes experienced by aspiring smallholders all over the continent throughout the nineteenth century.

But the audience immediately knows that this is a much more complicated story. As the play begins an Aboriginal extended family of five adults and two boys sit around a campfire. An Aboriginal narrator sets the scene speaking in English, but the group around the fire use Dharug, the local language. There are no surtitles. The audience does not know what they are saying. This was a bold decision by Bovell, Armfield and his associate director, choreographer Stephen Page. It made sense intellectually to have the Dharug speaking the language of the place. It emphasised the difficulty they had in communicating with the settlers and in turn their difficulty in trying to make themselves understood. In this way the audience is drawn directly into one of the great problems of the actual historical situation. But it is a tribute to the Aboriginal cast that they fluently use, what to them is a foreign language, with such ease of expression that for much of the time the gist of what is being said is grasped by members of the audience.

They are able to intuitively appreciate the way the Dharug experienced the tension and the misunderstanding inherent in the situation. But the full understanding is provided by the six settlers who Bovell chose from Grenville’s larger cast, who come and go on stage, and above all by Will and Sal Thornhill and their two sons who build their hut and plant their corn on the Dharug’s yam ground. At the very centre of the drama is the fact that the two groups both claim and endeavour to harvest the same plot of land. The flat, fertile land which produced the yams was also the best land for growing corn. The deep resonance of the situation becomes apparent to the audience. Bovell astutely uses Thornhill as a colonial everyman to articulate the ideas about land which were repeated endlessly all over the continent and justified the endless expropriation. The audience knows, as Thornhill cannot, that his situation will be recapitulated for generations to come under many different skies.

The central problem is articulated when we first meet the Thornhills. Will declares he wants a piece of land he could put his name on. ‘And why not?’, he asks. ‘It’s there for the taking.’ To which his wife replies: ‘But how can it be? What about those that are there?’ He responds: ‘They’re not like us. They keep moving. They don’t dig down into a place. They just move across it. Put up a decent fence and they’ll get the idea.’ In conversation with his son, Will observes:

A tent is all very well, lad, but what marks a man’s claim is a square of dug-over dirt and something growing that had not been there before. This way, by the time the corn’s sticking up out of the ground, any bugger passing in a boat will know this patch is taken. Good as raising a flag.

He tries to explain the situation to the traditional owners, declaring:

This is mine now. That’s a ‘T’, Thornhill’s place. You got all the rest. You got the whole blessed rest of it, mate, and welcome to it. But not this bit. This is mine.

Bovell’s dialogue allows us to understand the settlers’ lust for land. They had been cast out from a society where land ownership was the key determinant of status. It was unthinkable that they could ever have become proprietors in Britain. And it was the apparent ease of acquisition which gave promise of a better life at the antipodes and what reconciled them to their exile. It was what converted unwilling exiles into committed colonists.

Both Bovell and Armfield gave the production an added dimension by offering intimations of what might have been a more conciliatory outcome of the encounter. The younger of the Thornhill boys plays happily with his Dharug counterparts. Several of the settlers have achieved a sort of accommodation. The elderly widow, Mrs Herring, understands the importance of sharing. Thomas Blackwood, to the disgust of his fellow settlers, has taken a Dharug wife, Dulla Dyin, and has a mixed-descent child. Dulla Dyin uses traditional medicine to save pregnant Sal Thornhill’s life. Bovell and Armfield emphasise the common humanity of Dhurag and European in the set with the two families serially sharing the same camp fire.

But the tension inherent in the situation eventually engulfs everyone. It was an outcome that was to be repeated again and again as the settlers swept into new districts for the next hundred years. Armfield skilfully controls the increasing tension. Anyone who had read Grenville’s book knew what was going to happen. The settlers gather for what becomes a massacre of men, women and children. Thornhill provides the boat for the venture and takes part in the killing. Armfield eschews a scene of graphic brutality but is able to allude to the horror of it all, leaving the audience stunned.

There is then a double tragedy which gives the play greater depth. All chance of accommodation is lost and Thornhill, who is sympathetically portrayed, finally joins the brutal men of blood, personified by the egregious Smasher Sullivan. But it all begs the question of whether a more peaceful outcome was ever possible. The historical record suggests otherwise. The die was cast even before Thornhill was transported. The decision of the British Government to declare New South Wales terra nullius and refuse to recognise any indigenous land tenure was the over-mastering decision. The Hawkesbury settlers had every reason to assume the land in the valley was vacant Crown land. The Dharug therefore had nothing to negotiate with. There was no need for the settlers to learn their language or to understand their method of land use or form of government. But the British Government was even more directly culpable. With settlement extending up the Hawkesbury, the Governor and his officials realised they could not possibly police the frontier. They were forced to acquiesce in settler violence. Bovell uses the actual words of a proclamation issued by Governor Macquarie and published in the Sydney Gazette which are read to the settlers by Loveday – the one literate individual among them. The proclamation declared that if the Aborigines refused to leave land claimed by a settler they were to be ‘driven away by force of arms by the settlers themselves’. Loveday sums it all up with the observation: ‘Put plain, we may now shoot the buggers whenever we damn well please.’

The most portentous moment in the play is when Thornhill returns from Sydney with a gun. He had never owned one before and doesn’t know how to use it. But during the massacre he shoots Yalamundi, the senior man of the band whose land he had assumed was his own, putting the expropriation beyond doubt.

Bovell’s great achievement is to employ a small cast in a single location over a brief moment of time to unfold one of the archetypal stories of Australian settlement. It is for that reason that the play may well become one of the classics of the Australian stage.

May 2013

Henry Reynolds is an historian who works in Tasmania; his book Forgotten War was published by NewSouth Books in 2013.

Introduction

Andrew Bovell

The arc of Kate Grenville’s novel is epic. It tells the story of William Thornhill, born into brutal poverty on the south side of London in the late-eighteenth century, his place in the world already fixed by the rigidity of the English class system. In 1806 he is sentenced to hang for the theft of a length of Brazil wood. Through the desperate efforts of his wife, Sal, his sentence is commuted to transportation to the Colony of New South Wales. In this new land he sees an opportunity to be something more than he could ever have been in the country that shunned him. He sees ‘a blank page on which a man might write a new life’. He falls in love with a patch of land on the Hawkesbury River and dares to dream that one day it might be his. After earning his freedom he takes Sal and their children from Sydney Cove to the Hawkesbury to ‘take up’ a hundred acres of land, only to discover that the land is not his to take. It is owned and occupied by the Dharug people. As Thornhill’s attachment to this place and his dream of a better life deepens he is driven to make a choice that will haunt him for the rest of his life.

Sometimes the best approach to adapting a novel is simply to get out of the way. This proved to be the case with The Secret River. The novel is much loved, widely read and studied. It has become a classic of Australian literature. My task was simply to allow the story to unfold in a different form. It took me some time to realise this. Initially, I favoured a more lateral approach to the adaptation. I wanted to project the events of the novel forward in time and place the character of Dick Thornhill at the centre of the play.

Dick is the second-born son of William and Sal. Arriving on the Hawkesbury he is immediately captivated by the landscape and intrigued by the people who inhabit it. With a child’s curiosity and open heart he finds a place alongside the Dharug and they, perhaps recognising his good intentions, are at ease with his presence among them. Unlike his older brother, Willie, he has no fear of the Dharug and seems to recognise that they understand how to live and survive in this place. He learns from them and tries to impart this knowledge to his father. William Thornhill’s failure to learn the lesson his son tries to teach him is central to the book’s tragedy.

When Dick discovers that his father has played an instrumental role in the massacre of the very people he has befriended, he leaves his family and goes to live with and care for Thomas Blackwood, who has been blinded in the course of the settler’s violent attack on the Dharug.

One of the most haunting images of the book is contained in the epilogue. Thornhill, now a prosperous and established settler on the Hawkesbury, sits on the veranda of his grand house built on a hill and watches his estranged son passing on the river below onboard his skiff. He lives in hope that one day Dick will look up and see him. But Dick never does. He has made his choice and keeps his eyes steadfastly ahead, refusing to acknowledge his father and all that he has built.

Perhaps I was drawn to Dick because I’d like to think that if I found myself in those circumstances I would share his moral courage and turn my back on my own father, if I had to. I would hope that I too would refuse the prosperity gained from the act of violence and dispossession that the novel describes. I suspect, though, that like many at the time, I would have justified it as a necessary consequence of establishing a new country and found a way to live with it by not speaking of it. I would have chosen silence as so many generations of white Australians did.

It was here that I wanted to begin the play; on the moment of Thornhill watching his estranged son passing on the river. I created an imagined future for Dick. The novel reveals that Tom Blackwood had an Aboriginal ‘wife’ and that they had a child together. The gender of this child is not specified but I imagined that if she was a girl, that once grown, she and Dick might have ‘married’ and eventually had children of their own. So whilst William Thornhill and his descendants prospered on the banks of the Hawkesbury and became an established family of the district, another mob of Thornhills lived a very different life upriver, like a shadow of their prosperous cousins.

I mapped out a life for these two branches of the same family over several generations until I came to their contemporary incarnations. One family was white, the other black. I wondered whether they would be aware of their shared past and how the act of violence which set them on their separate paths would be carried through each generation, and whether reconciliation was ever possible between them. I imagined the story of Australia being revealed through the very different stories of these two families who shared a common ancestor and a dark secret. Importantly, in my mind was the idea that through the generations of Dick Thornhill’s descendents, Aboriginal identity had not only survived but had strengthened.

My collaborators, Neil Armfield and Stephen Page, and the Artistic Directors of the Sydney Theatre Company, Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett, heard me out but encouraged me to return to the book. They were right to do so. Perhaps by inventing this other story I was simply delaying the inevitable confrontation with the material at hand. Besides, Kate Grenville answered my curiosity about what happened to Dick Thornhill in her sequel to the novel, Sarah Thornhill. However, reaching beyond the source material into an imagined future was an important part of the process for me. I was trying to come to terms with the legacy of the violence depicted in the novel. I wanted to understand how this conflict is still being played out today.

When a connection is drawn so clearly between then and now, history starts to seem very close. I think this is one of the novel’s great achievements. In William Thornhill, Kate Grenville has created a figure modern audiences can recognise and empathise with. He is a loving husband and father, a man who wants to rise above the conditions into which he was born and secure a better future for those who will come after him. This aspiration seems to me to be quintessentially Australian, and Nathaniel Dean who played the role beautifully captured this sense of a common man.

Once Grenville has placed us so surely in Thornhill’s shoes she leads us into moral peril, for we find ourselves identifying with the decisions he makes. We may not agree with them but we understand them. And so we come to understand that the violence of the past was not undertaken by evil men, by strangers to us, but by men and women not unlike ourselves. That’s the shock of it. Grenville wasn’t writing about them. She was writing about us. Above all I wanted to retain that sense of shock.

A number of key decisions started to give shape to the work. We decided to use the device of a narrator. This allowed us to retain some of Grenville’s poetic language. We gave the narrator the name Dhirrumbin, which is the Dharug name for the Hawkesbury River. In effect she is the river, a witness to history, present before, during and after the events of the play. She knows from the start how the story ends and it falls upon her to recount the tragedy of it. This quality of knowing gives Dhirrumbin a sense of prophetic sadness. Ursula Yovich, who played the role, seemed to innately understand this. It wasn’t until I first heard her read the part that I thought it could work. She brought great dignity and presence to the telling. As well as performing the classic task of moving the narrative forward, Dhirrumbin stands apart from the action and is able to comment on it. Even more importantly, she is able to illuminate the interior worlds of the characters, particularly the Dharug, and hence act as a bridge to our understanding of their experience.

Building the Dharug presence in the play was fundamental to our approach, and became one of the key differences between the play and the novel. Grenville chose to keep the Dharug characters at a distance. They are seen only through Thornhill’s and the other white characters’ eyes, and their actions and motivations are explained through the white characters’ comprehension and often misinterpretation of them. In part, Kate chose to do this for cultural reasons. She felt there was a line that, as a white writer, she couldn’t cross and that it was not possible to empathise with the traditional Aboriginal characters.

We didn’t have that choice. It’s an obvious point to make, but in transforming words on a page into live action on a stage we rely on the work of actors. And we simply couldn’t have silent black actors on stage being described from a distance. They needed a voice. They needed an attitude. They needed a point of view. They needed language.