8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Deutsch

Seien Sie gewarnt! Sollten Sie sich von der in diesem Buch abgedruckten Gebrauchsanweisung inspiriert fühlen und tatsächlich zur Schere greifen, um die Doppelseiten aus dem Korsett der Fadenheftung zu befreien, müssen Sie sich auf einige Überraschungen gefasst machen. Be warned! Should the instructions printed in this book inspire you to actually reach for the scissors to free the pages from the corset of thread binding, be prepared, for there are quite a few surprises awaiting you.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Translated from the German by Katharina Debney.

Contents

How Everything Began

The Gallerist

The Proposal

Taking Care of Children

Post Scriptum

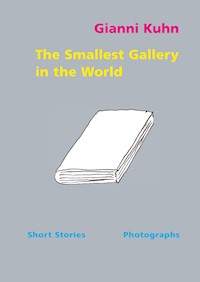

Short Stories and Photographs

How Everything Began

It was not as if I had been born writing. Although it is an appealing image how I, shortly after my birth, strengthened by my first meal from my mother’s breast, started to describe my journey through life so far: the nine months in the belly of my mother, swimming in this increasingly shrinking ocean, the sudden earth quakes, the flood waves, the suction, the sliding, being pressed, emerging, gasping for air, screaming.

As I lay in my crib, seemingly fast asleep, I could hardly wait for my mother to leave the room. I opened my eyes, grabbed the little notebook and the pencil stub, which I had both skillfully hidden at the edge of my tiny mattress – and began to work. I described how I felt, my relationship to my mother, who provided me with milk, smiled at me, talked to me, sang lullabies to me, cleaned my bum. But, unfortunately, I cannot find the «Book of the First Weeks» anymore. Maybe my mother, horrified, made it disappear. Who would want a precocious baby. If I ask her about it today, she says I am dreaming, that I had always had a vivid imagination.

I do remember the leaves on the tree swinging in the wind in front of our house very clearly, though. My mother had put me outside in the pram. I lay on my back and looked up to the swaying roof of leaves, behind which the sun flashed into view time and again. But did I know anything about trees, let alone maples, did I know what leaves are, what the sun is? Did I know what colors were, to what they belong, what they mean? Did I have a notion of photosynthesis, of sun and moon phases, did I recognize the woodpecker by its knock, the dog by its bark, the horse by its neighing? I could not talk yet, could not name to these things, just watched the spectacle in front of me impartially. And when my mother returned to fetch me, the things around me changed during my short trip in the pram back to the house. Other shapes appeared, it grew darker and then lighter again. And at night, when I lay in my little bed, a bright ray, a beam of light, darted through my room ever so often, grew and shrank, accompanied by a rattling noise. It came from the tractors of the farmers who took the fresh cans of milk to the dairy. But did I know what farmers or even tractors are?

When I think about my early childhood, the smell of cow dung and hay, of motor oil and sawdust, of white coffee and lard comes into my nose.

I hear the snorting of Max and Moritz, our two chestnut horses, whose nearly white manes used to fascinate me. Like billowing sails. But did I know what a sailing ship was, had I ever seen one? I suspect not even my father, who had never been to the sea until then, could have explained to me what comprised a windjammer, schooner or clipper, let alone what topmasts, yards, shrouds or rigging are. Our farm was not at the waterfront, was not bordered by shores, but lay deep in land, embedded in gentle hills. Here, the wind did not blow up waves as high as houses, but turned to the woods, which it transformed into a terribly raging sea during the autumn storms.

During the summer, the two horses were often restless, stamping their feet and swishing their tails, annoyed with the horse flies. To keep away these creatures, my father had hung a small bucket with a black liquid around their necks, which had a disgusting smell. Sometimes, my father lifted me onto the back of one of the horses, which he then led by the halter in a circle in the area in front of the barn. I actually sat on the broad and warm back of a horse, a proud rider. From up there, the world looked completely different.

Whilst my older siblings already went across the woods on their way to the school in the village, the woods became my home. I knew the clayey slope down to the stream, the smell of stagnant water, I knew the shallow places where large yellow flowers with huge leaves grew. There, I could cross the stream without problems. I also knew the dry places, such as the one under the ancient fir tree, whose branches reached down to the ground. There, I could not be seen, nobody could find me. When I strode through the woods and a deer came into view, when the sun conjured a playful dance of light and shadow through the twigs and leaves of the beeches onto the forest floor or when the rain produced a quiet melody, I was in a space where my innermost being and my surroundings had become strangely permeable, as if there were no real boundaries.