Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

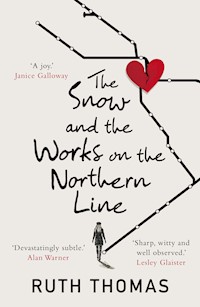

'Subtle, wry, intimate.' -The Times 'I LOVED IT! All the best bits of Barbara Pym, with a little Jane Austen - on speed' -Sarah Salway Hidden within the confines of The Royal Institute of Prehistorical Studies, Sybil is happy enough with her work - and her love life. Then to her dismay, her old adversary, assertive and glamorous Helen Hansen, is appointed Head of Trustees. To add insult, Helen promptly seduces Sybil's boyfriend. Betrayed and broken-hearted, Sybil becomes obsessed with exposing Helen as a fraud, no matter the cost. Offbeat and darkly funny, The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line is about things lost and found. It is also a story about love, grief and forgiveness: letting go and moving on.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line

‘I would follow Sybil down any Beckettian domestic rabbit hole.’

Reif Larsen

‘Sybil is an audible presence, someone that must be taken on her own terms, in her own words. The almost zen handling of voice is a joy.’

Janice Galloway

‘How can Sybil’s stint, indexing at the troubled Royal Institute of Prehistoric Studies, be so hilarious, so gripping, and so heart-rending? Because Ruth Thomas is a devastatingly subtle novelist – a quiet voice among louder ones, but, for me, a voice which says so much more about our crazy times.’

Alan Warner

‘A deeply involving novel about the end of a relationship, blended with a deliciously nutty confection of haiku and ancient history. The prose is sharp, witty and well observed – pitch perfect. Ruth Thomas has created an unforgettably nuanced central character, flawed and humorous with a fantastic sense of the absurd. It’s like reading about a best friend – from the inside out. Resonant and romantic, sad but never sentimental and laced through with wicked shafts of humour.’

Lesley Glaister

‘A very funny novel with a dark undertow. Ruth Thomas creates a world which is vivid, emotionally true and acutely observed. Sybil’s voice is compelling – both knowing and unknowing – and the dialogue bristles with the unsaid. Wry, sharp and tender. A delight.’

Meaghan Delahunt

‘I LOVED IT! All the best bits of Barbara Pym, with a little Jane Austen – on speed.’

Sarah Salway

Also by the author

Sea Monster Tattoo

The Dance Settee

Things to Make and Mend

Super Girl

The Home Corner

Ruth Thomas is the author of three short story collections and two novels, as well as many short stories which have been anthologised and broadcast on the BBC. The Snow and the Works on the Northern Line is her third novel. Her writing has won and been shortlisted for various prizes, including the John Llewellyn Rhys Award, the Saltire First Book Award and the VS Pritchett Prize, and long-listed for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. She lives in Edinburgh and is currently an Advisory Fellow for the Royal Literary Fund.

First published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Ruth Thomas 2021

Editor: Moira Forsyth

The moral right of Ruth Thomas to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-37-3

Sandstone Press is committed to a sustainable future.

This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council ® certified paper.

Cover design by Rose Cooper

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

For M.G.N.

Amongst the graffiti is the name of someone I love

Bashō

THE SNOW

1

The accident was one of those stupid ones. It was the kind you’re supposed to laugh about later. It happened at Streatham Ice Rink; Simon had thought it would be fun to go there one evening, so that was what we did. Unfortunately, neither of us could skate; this had not occurred to us. Simon was better than me – he was able to stand upright without holding onto the side – but I did not enjoy myself a single minute I was there: my skates were as heavy as leg-irons, and the rink just seemed to go on and on: you could hardly see across to the other side. I was wearing a bobble-hat that my mother had given me one Christmas years before, and an over-sized Parka that Simon had lent me, and I kept wondering why on earth you were supposed to skate on single blades when two per boot would have been so much more sensible; I couldn’t understand why no one in the skates business had ever thought of that. Looking up at one point I saw a blur of gold and silver tinsel draped around the crash barriers, and looking down I saw a large brownish-red patch beneath the surface of the ice. I thought: that’s someone’s blood. And I wondered how often the Management at Streatham Ice Rink thawed the ice so they could get rid of things like that, little signs of something that had gone wrong.

We’d been there for ten minutes or so, slogging around as people span and twirled about us when Simon said, ‘Oh, look – isn’t that what’s-her-name over there? Your old lecturer? Who was at your Christmas work thing the other night?’, and he suggested we push out towards the middle of the rink, to see if it was.

I glanced over for a second, at my one-time university tutor and new work associate, Helen Hansen. I couldn’t imagine what she was doing there. It seemed enough that I was always bumping into her in the corridors at work. Her complexion was a rosy, athletic pink beneath her snowy-white hat and she was wearing a puffy, expensive-looking ski-jacket that looked as if it would have been better suited to the French Alps than Streatham Ice Rink. ‘I’m not sure it is her . . .’ I said. Because if it was Helen Hansen, I didn’t really want to speak to her. There was a certain history between us, and everything on the rink was a blur anyway.

‘It is her,’ Simon said. ‘We should say hello. It’ll be easier out there, anyway. More space.’

‘Will it?’ I flicked a quick glance at the slab of ice beneath my boots. ‘But do we want more space? I’m not sure I want to say hello . . .’

‘What’s wrong with her? She’s perfectly nice. We had a good chat the other night.’

‘Really?’

But because he was taller and broader than me I made the mistake of thinking he was also more stable on slippery surfaces, more dependable. I did not say, ‘I think this is a bad idea; I once heard of someone leaving an ice rink minus half their fingers.’ We just lurched out into the middle, towards Helen Hansen: archaeologist extraordinaire, rising businesswoman-cum-academic star, member of the Institute’s Board of Trustees. It was a Friday night and the rink was packed with very tall fifteen-year-olds and couples who appeared to be so good on the ice that they were snogging while skating, and there was a soundtrack playing very loud and distorted from metal speakers jutting out across the rink – some Lionel Richie song I vaguely knew – and we were a long way out now, sliding like Brueghel’s peasants towards her, when I misjudged some technique I’d adopted for staying vertical, and felt myself slip. And straight away I knew this was not going to end well. Moving semi-horizontally, I reached out for Simon’s arm – ‘Wha—?’ he said – then we were both on our backs on the ice, the air knocked flat out of us, and spinning like bottles.

I’m not sure what happened after that. There was a lot of whiteness and coldness, the whole ice rink upside down and lit up and moving in a rush of tinsel and jackets and faces. There were steel skates everywhere you looked, only now they were all at eye level, and Simon and I were rocketing towards the crash barriers, heading there fast, and I put my arm up to protect my head from the impact I knew was about to happen, and Lionel Richie was telling us it was quite a feeling, dancing on a ceiling and the fifteen-year-olds were braking all round us in a spray of ice-splinters and contempt. And for the briefest moment, I had a strange vision of my grandfather, of all people, who’d died a few months earlier: there was my grandad, as clear as daylight in my mind, and I thought: well, if I’m about to die it’ll be OK because Grandpa’s here to show me the ropes. Then we hit the barriers, head first, and for a while after that I was nowhere at all.

A little later I was somewhere, of course: I was not in heaven with my grandfather, I was still living and breathing in some ward in Dulwich Community Hospital. I was in the same old world and it was late December, and Simon was so unscathed he’d already left Outpatients and headed home on a bus. He’d gone with Helen Hansen, in fact. Because it had been her. And really, it was quite a miracle that neither of us was not more badly hurt. Helen mentioned this herself, when she put her head round my door at work a few days later; she’d turned up again for one of the Trustees meetings she kept going to.

‘So someone was looking out for you last week, Sybil!’ she said, in her sassy way. And she smiled that big smile of hers.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I suppose they must have been.’

I looked down at my desktop, and couldn’t think what else to say. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘thanks for coming to the hospital with us, Helen. That was nice of you. As neither of us was particularly compos mentis at the time.’

Because I’d been brought up to be polite – even to people I didn’t actually like. Then I smiled briefly and got on with my work, and everything around me had looked much the same, for the next few weeks. It all was much the same. I just hadn’t realised it was about to look different.

I hadn’t seen her for ages, before that. Not for nearly seven years. But whenever I thought back to those days, I’d remember how she had seemed to quite like me. She’d made a strange beeline for me – something I’d never really understood. I’d been a young first-year student, awkward as a goat, and she was a glamorous academic heading towards a doctorate. I’ve since learned that some people operate like this. They like to bask in other people’s reflected lack of glory. But I didn’t know this at the time; I’d just accepted her attention with bafflement and a vague wish to get away. Two things stood out in my memory: once, during a tutorial on funerary urns, she’d flattened a wasp with a plastic Helix ruler, squashing the life out of it rather than simply letting it fly through the open window and, halfway through our first term together, she’d started calling me Sybil the Blind Prophet. This was, she said, an affectionate joke. ‘It’s meant to be a compliment, Sybil! It’s because you know so much! You seem to know things by some mysterious osmotic process, and I can never work out how you do it!’ I’d always thought that was peculiar, too. My ability to retain any information at all really seemed to bother her.

At the end of my university days I’d gone to Swansea to do a post-graduate degree in Norse and Celtic Mythology, and although I’d heard occasional news of Helen’s starry progress through academia via a journal called Archaeology Now!, which my old department intermittently brought out and sent to me via my parents’ address in Norfolk, I’d assumed our paths would not cross again. I was perfectly happy about this: quite content to hear news of Helen through the pages of Archaeology Now! It was, for instance, where I’d first learned of her unexpected departure from my old university in order to take up an exciting new role as Director of the London Museums Interpretation Centre, in Tooting. I’d opened that issue during a weekend stay at my parents’ house, and there she was, in the centre pages, standing beneath the diplodocus skeleton in the grand hall of the Natural History Museum. She was clasping a champagne flute, her blue eyes flashing, her jaw set at an ever more resolute angle. ‘I see my role as facilitating the various commercial opportunities available to museums and academic institutions in the twenty-first century, while remaining sympathetic to and respecting the core values and aims of historians and archaeologists . . .’ she’d proclaimed, in an interview beneath this picture. The London Museums Interpretation Centre (LMIC, for short) was, apparently, a much-needed new umbrella group for smaller British museums, channelling funds, arranging networking events and reaching out to new audiences and consumer markets.

‘Well, she looks like a force to be reckoned with,’ my father had observed, peering over my shoulder at the photo. ‘Tooting, though? Seems an unlikely place.’

‘But where’s a likely place?’ I asked. ‘For someone like her?’

‘I don’t know, New York? Tokyo? Paris? Somewhere glamorous.’

‘Oh.’

He glanced at the picture again. ‘Helen: the face that launched ten thousand ships.’

‘One thousand,’ I corrected him.

‘What was it she used to lecture you on?’

‘Beakers. As in The Beaker People.’

‘Oh.’

He looked vaguely disappointed.

*

I had not done much myself during my years in Swansea, after the perfectly respectable 2nd class Honours degree I’d wrested from the jaws of the 3rd class one Helen had (as I later discovered) recommended. I’d read The Mabinogion and the Arthurian legends and written a dissertation on The Book of the Dun Cow (a book I’d initially assumed was about a cow: I was wrong.) I had fallen in love for a while with a long-haired Irish legends specialist who’d smoked a lot of weed, never got out of bed before 3pm and owned a lime-green mug that said Time and Relative Dimension in Space. I don’t know why the memory of that mug loomed so large in my mind, it just did. Then I’d returned to London and had an unexpected fling with a Danish astrophysicist called Mats, before moving on to a bearded and more sensible man named James who was doing a PhD and had been doing so for years. I imagined he would be about forty-six before he submitted it. He used to make a lot of gnomic and profound remarks and he also sometimes made me laugh. But after a while his immense, serious wisdom had begun to weigh me down, the way too much snow weighs down a too-thin branch, and I moved on from him, a little sadder but, paradoxically, lighter of heart.

I was alone for a few months after that, and then I met Simon: we met one night in The Olive Branch, an Italian restaurant round the corner from my flat, where he worked as a chef. I had gone in alone, a young woman about town, and ordered salted cod by mistake, and after I’d returned it and he’d appeared at my table with a replacement bowl of spaghetti al pomodoro and said he’d made the pasta himself, not from wheat but from spelt, it was pretty much love at first sight; I suppose it was what is called a coup de foudre. Even though we were not actually alike at all, it soon transpired, and we didn’t even like doing the same things. He was an active sort of person, whereas I’d always preferred observing other people being active. He liked driving his boss’s Alfa Romeo around town, and I liked going to the cinema and watching other people driving their cars around. He liked outdoor pursuits – foraging, hiking, wild camping – while I couldn’t stand windswept walks up uneven gradients, or eating fungi that might kill you, or listening to disconcerting noises outside a tent at three in the morning. But love is not concerned with such differences, of course; love does not have motives or reasons or ambitions or even shared tastes. We’d simply fallen for each other: we were yin and yang, light and shade, Mr Sunshine and Mrs Rain in their little wooden house. It didn’t seem to matter that he was pragmatic and I was a conjecturer; that he made things, and I wondered about them; that he was an outstanding and inventive cook, whereas I was mostly a compiler of sandwiches. At the end of the day I would turn the key in the lock of our front door (we moved in together less than a year after first meeting), and would feel happy if he was already home, frying shallots or chopping herbs from the little pots he kept on our kitchen windowsill.

Of course, I did worry from time to time about the ways we were different, and perhaps, it occurred to me later, I should have worried a little more as the months went by. Maybe if I’d thought, for instance, about his decision not to go with me to my grandfather’s funeral that autumn because he’d hardly known the guy; or reflected on the camping trip we had gone on just two days later, because camping was extremely important to him – and how, although I loved the pine-scented woods and the craggy hills and the birds flapping around the sky, I’d felt a terrible, lonely ache in my chest, and it had been clear to me within five minutes of pitching the tent that he was going to enjoy himself a lot more than I was. He was in his element, striding around the fields in his North Face windcheater while I was only in my element in theory. I’d taken my guitar along to play a few songs, but even as I sat there, picking out Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd tracks on a slightly sloping patch of damp grass, I knew I could never be truly excited about a holiday that involved washing up in a stream with a Brillo pad and gathering sticks; I knew that, at heart, I really wanted to be at home, missing my grandad, and watching QI in my slippers. We spent a lot of our first day trying to work out where we were in relation to the nearest village (we were fourteen miles away) and boiling up farro grains in a tiny saucepan, the clip-on handle of which kept falling off. Then halfway through Day Two, scouting in the woods for a suitably private patch of bracken, I’d peered up to witness a farmer appear puce-faced over the brow of the hill on a quad bike, yell something and wave his arms, before a flock of about fifty sheep came careering into the field where we’d pitched our tent.

‘The thing is,’ I said to Simon that night, as we sat in the greenish shadows, ‘we do actually live in the twenty-first century. So why pretend we still live in the Bronze Age?’

He looked at me. He looked very serious, almost sad, as if some fundamental truth had just occurred to him, about the many ways we would never understand each other. Maybe he was thinking: If we were depending on you for survival we’d have another forty-eight hours, max. But then he smiled.

‘Come here, twenty-first-century girl,’ he said, unzipping the sleeping bag which he’d bought especially for me, because it was a 4-seasons tog rating, and I slid along the sloping nylon groundsheet towards him and slung my arms around his neck.

The thing is, we were not always on the same wavelength. But this didn’t mean I didn’t love him. It did not mean I didn’t care.

Then, one afternoon a few weeks later – the same afternoon (it transpired) that Helen returned to my life – we had an argument. It had a depressingly trivial cause, as arguments often do: I’d suggested, as we were washing up the previous night’s dishes, that it might save space in our tiny kitchen if we stacked all our saucepans under the sink with their lids inverted. And Simon had said actually, no, you should always hang saucepans by their handles from a rack above the cooker.

‘If you stack them,’ he explained, ‘you have to dismantle the entire stack to use them, and no proper cook does that!’

‘Oh, really! So are you saying I’m not a proper cook?’

‘Well, to be honest, you are pretty crap at cooking!’ He stared glumly down at the draining rack. ‘Also, I was going to let this go, but why did you use my rice steamer to steam fish in last night?’

‘What?’ I said, blushing – because he was right, I had used his rice steamer to steam fish in, the previous night.

‘The whole thing reeks of cod now!’ he said. ‘I’ll have to throw it out and get another one!’ And somehow, within about fifty seconds of my quite casual remark about saucepan storage, our disagreement had escalated into something a lot worse: something intense and loud and hurtful.

‘It’s clear to me you have no real interest in food!’ Simon was saying now. ‘I mean, all your cooking seems to be variations on a theme of tomato sauce!’

‘Hah! Well, that’s because I don’t want to spend half my life fluffing wild rice!’ I yelled back, aware of a strange, almost physical hurt – it felt like a big punch in the stomach.

We glared at each other. It was as if neither of us could imagine what we’d ever once admired. Then, sad and rattled at this new depressing turn in our relationship, I picked up my coat and keys and barged down the hallway out of the flat.

‘Don’t wait up!’ I yelled (even though it was only three in the afternoon) and I slammed the door and hiked off up the road. I headed to the tube station, walking fast but directionless, aware of myself gulping at the air like a fish. By the time I was through the ticket barrier I already felt contrite, depleted, but despite this I carried on, heading all the way into town on the Northern Line, all the way up to King’s Cross and out again onto the Caledonian Road, then up to the British Library, for some reason – and it was at this point, in the gathering gloom, that I first bumped into Helen.

‘Sybil!’ a voice called to me across the wet, paving-slabbed courtyard.

And I turned, and there she was: this woman, waving, beside the statue of Sir Isaac Newton. It took me a second, maybe two, to recognise her, to comprehend why I knew this impressive-looking person with the big smile and the blonde hair and the smart coat. Then, when I did realise, I felt something happen to my heart: a kind of jump, a sort of lurching.

Helen had already abandoned Sir Isaac Newton and his set of compasses by this point, and started walking across the square towards me. It was raining slightly and she was holding a navyblue umbrella – one of those big expensive ones that does not immediately buckle in the wind, unlike the flimsy telescopic things I was always buying.

‘Come under my brolly,’ she instructed, and I did. I did as I was told. And I saw that she had hardly changed at all. Her hair was the same, and her smile was the same, and even the coat was like the one she’d worn around the corridors of UCL – although this one was new and even more expensive-looking. Also, she still had a very sassy walk and a confidence that seemed to flatten everything in its path. We smiled a little over-enthusiastically and gave each other a hug beneath the spokes of her huge umbrella and went into the library through the heavy glass doors. We bought two coffees in paper cups and sat down at one of the round white tables in the foyer, even though by now I was already wanting to go back home to Simon, to apologise, to be apologised to.

‘So tell me what you’ve been up to all this time, since our cosy tutorial-group days!’ Helen said, but I had begun to feel strangely pinioned by this point because I suddenly remembered just how un-cosy our tutorial-group days had been, and how much effort Helen had put into trying to scupper my 2:1. A disappointing collection of un-referenced and historically inaccurate theories, she’d called my dissertation (I found out later) – though oddly, she’d been in the minority with this opinion because it had been contested that summer by the head of department, who’d described it as: A diverting and audacious comparison between the myths of Classical Literature and the facts of prehistory. (He’d said this during an exam board meeting, and it was his opinion which had won the day. Even though, secretly, I suspected Helen had probably been right all along.)

‘I mean,’ Helen went on brightly, smiling across the table at me, ‘where has life taken you, Sybil?’

‘Well,’ I replied, ‘I hardly know where to start, Helen. Because seven years is a long time.’

‘It is, isn’t it?’

Then she embarked on what she’d been doing in that time: how she’d been briefly married and divorced; how she’d travelled to Beijing and Toronto and Tokyo (‘So my dad was right!’ I almost burst out); how she’d left the university and had recently become the director of a place in Tooting called the London Museums Interpretation Centre – (‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I read about that!’) – which was an exciting career move, Helen ploughed on, because not only was the work fascinating and fun, but the perks and the bonuses and the social life were excellent, and she could also wangle more funded conference trips to China and Canada and Japan, thereby enhancing her reputation as a Beaker People expert. Which was the real point.

‘That sounds great,’ I said. ‘Getting the chance to, y’know . . . continue your research. And go to Tokyo. Wow! I’ve always wanted to go and see what—’

‘Yes, it’s great,’ Helen confirmed.

I hesitated. I still felt oddly numb, after my argument with Simon. ‘So you’re still specialising in . . . ancient peoples . . . ?’

Helen gave me a funny look.

‘Of course I’m still specialising in ancient peoples! Ancient peoples are my life. The Beaker People in particular. I’m pretty much a world authority on them these days, Sybil. I’ve even recorded a TED talk recently.’

‘Wow,’ I said, even though I’d never been sure about TED talks; they’d always sounded quite overwhelming to me, like a cross between bears and Ted Hughes. Also, I was not convinced Helen was a world authority on the Beaker People, though I knew she’d always been ambitious. ‘So what’s it about? Your talk?’

‘It’s about the Beaker People in general, and, more specifically, about a discovery I made earlier this year, during a dig in Sussex.’

‘Really? In Sussex?’ I said, feigning interest.

‘Yes, my team and I came across some extremely exciting pottery fragments there, in Winchelsea. I’ve called it the Winchelsea Hoard—’

‘Wow, amazing! Like Sutton Hoo or something!’ I said, trying to maintain the note of wonder. Somehow, though, the words extremely exciting and pottery fragments had never quite gone together in my head.

‘Yes,’ Helen said, ‘we found a whole stash of Beaker fragments in a field just up from the beach. Analysis of which suggests that Beaker trade routes went much further into Southern Italy than we’d thought.’

‘Italy? But I thought you found them in Winchelsea.’

‘We did,’ she snapped. ‘But finding them there, in Winchelsea, has opened up a whole new set of ideas about their trade routes.’ She looked at me. ‘Because of the type of grain residue that was in them.’ She paused, as if waiting for my slowly whirring brain to catch up. ‘Hence my extended trade route theory. Which is what I talk about, in my TED talk.’

‘Well, wow . . .’ I said. I didn’t know what else to say. It was like being back in one of her tutorials. There was the same desire to get away. ‘So what were they? These grains?’

‘A variety of turanicum wheat from Southern Italy. And as we know, or thought we knew – that’s the only part of the Mediterranean the Beaker People were not supposed to have lived in!’

Triumphant, she stopped talking, and waited for me to speak.

‘Well, that does sound exciting,’ I mumbled.

I thought of my dissertation again, in which I’d ad-libbed wildly on parallels between the Beaker People and the mythic significance of goblets and chalices in Ancient Rome, which was all a load of rubbish, of course; I’d had no evidence for this at all.

‘So, when’s it going out?’ I asked. ‘The talk?’

‘In the spring. It’s in post-production. I’m focusing on PR stuff now.’

‘Right.’

‘Yes, so what I’m doing at the moment – mainly to get LMIC’s role more out there, in the public consciousness – is I’m developing a range of Beakerware kitchen products with my colleagues in Tooting.’

‘Really? Beakerware?’ I thought of the Tupperware my parents had always used to bring out on picnics when I was a child; of our serious little party of three, at the beach at Dymchurch or Camber Sands.

‘Yes. We’re going to sell a range of replica beakers – earthenware bowls and cups of different sizes – in various museum shops next summer. Even in places like the British Museum, if they’ll have us. Eventually we’re hoping to roll them out across Europe.’

‘Roll them out?’

‘Expand the market. Then we’ll channel the profits back to LMIC. Via our own museums, of course.’

‘I see,’ I said.

‘The thing is, small museums are hopeless at commercial enterprises,’ Helen explained. ‘So it’s LMIC’s role to get them on board. They get the money and we get the kudos. And museum shops are awash with idiots wanting to part with their cash.’

‘Yes.’ I thought of the occasions I’d drifted around museum shops with Simon lately, picking things up – pyramid-shaped pencil sharpeners, key rings in the guise of Viking warriors. ‘Would you like some earrings in the shape of hippo gods?’ he had asked me recently, holding one up to his earlobe.

‘Probably they’re just, you know, parting with their money because they’re having a nice time,’ I said now. ‘Just being tourists. And feeling a bit flush because they’re on holiday. And wanting some sort of . . . souvenir of their time.’

Helen smiled, as if I might be one of those idiots. ‘The Beaker People never interested you much, did they?’ she said.

‘Not really. The thing is,’ I added, making it worse, ‘they just kept making beakers all the time! And I’ve never been all that interested in bits of broken pottery.’

Helen’s eyes were a quite spectacularly icy blue.

‘Do you know how many museums we have under our belt at the moment?’ she asked.

‘No.’

‘Eleven.’

‘Right.’

‘And do you know how many we plan to have by the end of next financial year?’

‘No.’

‘Eighteen!’

‘Right.’

‘So, what are you up to now? By way of gainful employment?’ she added, stirring sugar crystals into her coffee. So I told her that I was – funnily enough – working in a kind of museum myself, these days: I was cataloguing fossils and belt buckles and old clay pipes, amongst other things, in an institute.

‘Really? But that’s hysterical! That’s hardly a million miles from bits of broken pottery, is it?’

Well, no, I confessed, it wasn’t. It’s just, there weren’t any jobs, when I was looking, that required an in-depth knowledge of Persephone or Zeus or Apollo, or even The Book of the Dun Cow.

‘So where are you doing this?’ Helen asked. ‘The cataloguing?’

‘Greenwich,’ I said. ‘In the Royal Institute of Prehistorical Studies.’

‘You’re working at RIPS?’ she burst out. ‘At the Institute? With Raglan Beveridge? And Hope Pollard and people? How utterly bizarre! That’s one of our museums! It’s our latest recruit! So how come I haven’t seen you there, because I go there most weeks!’

‘Well, I only started there quite recently,’ I said, suddenly alarmed, and wishing I’d kept shtum about the Institute and my opinion of the Beaker People. Or that I’d never turned around when Helen had called over to me from the Isaac Newton statue.

‘So hopefully we’ll be seeing more of each other,’ she continued. ‘Isn’t that funny? Hey – we can go for lunch sometimes and bitch about Raglan!’

‘Hmm . . .’ I wasn’t sure I wanted to bitch about Raglan Beveridge, because although I didn’t know him well (he was, after all, the Institute’s director), and although he was a big man in his fifties and perfectly capable of looking after himself, I’d noticed a kind of vulnerability about him sometimes that made me feel it was unkind to talk about him behind his back. It was something to do, somehow, with the very careful way he wore his suits and the fact he was invariably the last person left in the building when everyone else had headed home. Anyway, as my mother would have reminded me, if you can’t say something nice about someone, don’t say anything at all. And already something was telling me that bumping into Helen had been a more troubling thing than I might have anticipated, that it was stirring up some quite unwelcome memories.

Helen smiled.

‘You know, I’m so glad you ended up with that 2:1 in the end, Sybil,’ she said. ‘For that dissertation you wrote. All those years ago.’

‘Are you?’ I asked, my heart thudding.

‘I really am. You deserved it. Because clearly I was the one who got it wrong on that occasion, wasn’t I? As it turns out.’

‘Well,’ I said, remembering the unseemly haste with which I’d cobbled it together, ‘that’s very—’

‘I was too exacting. Not forgiving enough. It’s easy to forget sometimes that your students are only just out of school! Barely more than children! And the thing is, it’s important to own up to your mistakes, isn’t it? If we never made mistakes, we’d never learn.’

‘No . . .’

‘Seriously, though, I suppose what happened, that time, was I’d discounted that pretty interesting correlation you made between the Beaker People and stories about Ancient Roman cup-bearers. That “everything is connected” idea. It was just that Ancient Rome was not my area, of course.’

‘No.’ I could hardly remember the correlations I’d made. They’d been a means to an end, conjured up out of thin air when I was twenty. I just wanted to return to my life now at twenty-six, and the people I knew and trusted in it – even to Simon, especially Simon, despite the ridiculous argument we’d just had. Because he was my lover, he was my friend and confidant, he was maybe even my husband one day and the father of my children. But Helen seemed to want to keep chatting, and it was hard to know how to get away from her. She was telling me now about someone at work called Ed whom she’d been seeing for a while but was thinking about leaving, and also about the man she’d been briefly married to, whose name was Doug. They’d never been compatible, though, because Doug was so unadventurous and had a secret liking for David Gray and Phil Collins and all sorts of other deplorable middle-of-the-road music—

‘But I thought you quite liked Phil Collins,’ I said, pulling my coat from the back of my chair and dragging it on. ‘I remember you playing “In the Air Tonight” once, in one of our tutorials.’

Helen frowned. ‘That was to explain a point. About carbon dating. Because, if you recall, I always tried to make my tutorials fun.’

‘Oh, I didn’t realise! I’d just assumed you liked—’

I trailed off. Helen was peering at me again in quite a disconcerting way.

‘So, how’s your love life?’ she said.

‘Sorry?’

‘Got a significant other?’

So I sat there a few minutes longer, and told Helen about Simon: about, amongst other things, his strange enthusiasm for ancient grains, and the funny black-and-white checked trousers he’d worn in his first job as a chef, and his love of mushroom foraging and wild camping and listening to Bob Marley. I even showed her the picture I had of him in my purse. Then for some reason I also found myself telling her that he hadn’t gone with me to my grandfather’s funeral – a fact that had upset me quite a lot at the time, I went on – and also about the ridiculous argument we’d just had about saucepans.

‘But then again,’ I added, ‘I think I probably overreacted. Because people respond differently to death, don’t they? To grief. And I suppose it must be pretty annoying, if you’re a professional chef, to see your rice steamer being used to steam fish in . . . And I do love him. And maybe arguments, if you resolve them, can actually be a testament to . . .’ I faltered.

‘To what?’

‘A grown-up relationship.’

‘Hah! Not in my experience!’

She gazed at me across the top of her paper cup. ‘It’s funny,’ she said, ‘because I never imagined you with an alpha male type, Sybil. I always thought you’d end up with some poetry lover, wafting around playing a guitar.’

‘Oh, Simon’s not an alpha male type, really,’ I said. ‘He’s pretty much beta, in a lot of ways.’

‘Trust me, a man who likes his woman in the kitchen with her saucepans is an alpha male type.’

‘He doesn’t want me in the kitchen with saucepans,’ I said, exasperated. ‘He actually wants me out of the kitchen! And if anyone’s interested in saucepans, it’s him – he’s even got a little Trangia set for when he goes camping!’

Helen paused. ‘How sweet,’ she said thoughtfully.

I suddenly wished I hadn’t divulged this information.

‘I’m quite a fan of camping myself, actually,’ Helen went on. ‘Good-looking guy, isn’t he?’ she added.

I did not reply. I found it hard to imagine Helen Hansen sleeping under canvas, even if she was an archaeologist. And Simon was good-looking, but I did not see the need to share this insight with her. So instead, I told her a little more about his work: the pasta and the pizza doughs he made, the different types of grain he’d started experimenting with at The Olive Branch. Because, I explained, it was one of those very artisanal restaurants that seemed to be springing up all over the place. He had shown me a list of ingredients when he’d come home recently. ‘Look at this,’ he’d said. There was buckwheat, spelt, brown rice, quinoa and amaranth; there was barley, freekeh and rye. ‘Freekeh!’ I’d laughed. But he hadn’t seemed to find it such a funny word as I did.

Helen glanced at her watch. ‘Bob Marley was a fan of multiple relationships, wasn’t he? So I believe,’ she said, looking at me with her impressively blue eyes.

‘What’s Bob Marley got to do with it?’

‘Simon likes Bob Marley, you just told me. Keep up, Sybil!’ she said. Which was what she’d used to say to me sometimes, during tutorials. Keep up, Sybil the Blind Prophet! Although when I had eventually kept up, surprising everyone with that 2:1 and a personal little note of praise and apology from the head of department, she had said nothing to me at all.

‘Do you remember that boy in our tutorial groups?’ she said, as we stood up from the table. ‘John Milton? Who wrote poetry?’

‘Of course I do,’ I said. ‘Except his name was John Nelson.’

‘He seemed more your type, I always thought. John Milton. I always thought you two might get it together . . .’

‘John Nelson,’ I tried again. But really, there was no point. Helen was not listening; she appeared, rather, to be working something out. I even mentioned this to Simon a few hours later, after I’d gone home and promised to buy him a new rice steamer, and we’d kissed and made up. Yes, I observed that evening as we lay in each other’s arms, gazing through our bedroom window at the darkening sky, yes, there’s something even steelier about her these days . . .

‘Stealier?’ he said, his voice floating up into the darkness. ‘What’s she been stealing?’

‘Steelier.’ I laughed, stroking the underside of his arm, where his skin over the muscle was so beautiful, so soft as silk. ‘Steelier, with two es.’

Although, as it turned out, his interpretation had been the correct one.

2

Floor 0

Gallery

Floor 1

Reception

Floor 2

Offices

Floor 3

Offices

Floor 4

Offices

Floor 5

Archives

The Institute stood in the middle of Greenwich Park, half a mile north from the General Wolfe statue and half a mile east of the meridian line. You could place your feet on either side of the line and be in two different hemispheres at once. I did that sometimes, on my way up the hill in the mornings. It only worked as far as geography was concerned, of course; unfortunately it was not possible to do the same thing with time.

I’d actually used to wander around the park years before, as a child; I’d gone there with my grandparents who’d lived nearby, in Blackheath. We’d drive there in my grandad’s Triumph Acclaim then walk slowly, slowly across the grass, down past the doors of the Institute and on, down Greenwich High Street, to look at the Cutty Sark. Or we would walk through the Greenwich Foot Tunnel, our footsteps echoing against the curved white walls. I’d walk between the two of them, holding onto their hands. ‘A rose between thorns,’ my grandfather used to say. I didn’t know what he was talking about.

*

The Institute’s full name was the Royal Institute of Prehistorical Studies but this was usually shortened to RIPS – an acronym even its first employees found amusing, apparently, when it was founded in 1908. The building itself was Victorian, and ‘still a seat of learning and intellectual endeavour’ (as Raglan Beveridge had said in his latest Annual Report). In the 1950s its research remit had broadened to include historical as well as prehistorical artefacts: there were now some staff who studied objects left behind by relatively modern peoples – peoples with an s – though its focus was still mainly on ancient pottery and bones. It had fallen on hard times in the 1990s and early 2000s, suffering from a lack of core government funding, but more recently it had started to receive sponsorship from various commercial enterprises, in particular, from the London Museums Interpretation Centre. Yes, LMIC had swept in, with its youthful energy and its commercial chutzpah! – and these days, as Raglan had also said in the report, RIPS was back on the map.

There was still a fusty quality to the place, though.

I liked that. I liked its fustiness, and the way time seemed to move so gently there, settling in layers. A week or so after I’d first bumped into Helen again, there’d been a small fire in the roof space, and when the staff gathered in the car park, I was surprised to realise how many people actually worked there. I’d never even seen some of them before. They appeared to have spent so many years in their rooms analysing finds that, in the daylight, they looked quite preternaturally pale. They reminded me of some tinned hearts of palm Simon had recently put in a salad. Or the axolotl specimen that lurked, alabaster-white and rubbery, in the Comparative Zoology Gallery. I’d spotted Helen that day for the first time since she’d told me about her connection with the place, and my heart had sunk a little. She was hanging out with all the time-served old members of staff in one of the parking bays. She’d somehow looked about twice their height and a hundred per cent healthier and in colour, instead of black-and-white.

There were five floors in total in the building, six if you included the gallery in the basement. These were called Primordial, Sedimentary, Sandstone, Igneous, Chalk and Shale. A few of the Trustees still called them that, anyway; everyone else just called them floors. Each floor was composed of six large rooms and various smaller side-rooms. I worked on the fifth floor, where I had a view right across the park and of the beautiful silvery ribbon of the Thames. On the floor above mine were the Prints and Archives and the Special Collections Rooms, and at the bottom of the building was the Carbon-dating lab, and housed at one remove, in a large, converted ice house a few hundred yards away, was the Printing and Reprographics department. I’d quite often go upstairs to Prints and Archives and Special Collections, but I didn’t go to Printing and Reprographics if I could help it, mainly because John, the man who worked in there, did not seem to appreciate too much interruption. I think it suited him to be alone. I hardly ever went down to the Carbon-dating lab either, mainly because there was a large sign on the door saying Danger of Death. And I didn’t want to die. Also, I didn’t want to go crashing in there at the wrong moment and wreck someone’s data analysis. One of the palaeontologists, a rather baleful trilobite specialist named Professor Jeremy Muir, had informed me recently that even breathing could affect the date-reading of something. So another thing I did, if I ever ventured in there, was hold my breath.

One of the rooms that intrigued me most at RIPS was a largish office located on the second floor. Everyone referred to this as Peter’s Room, because it had until quite recently been used by a member of staff named Peter Edwards. Peter Edwards had died though, shortly before I started at the Institute. He’d died while researching ‘in the field’ – a fact that always struck me as sad, whenever I went in there to look for a book or answer the phone that still rang sometimes on his old desk. There was something melancholy about that phrase ‘in the field’. It made me think of Captain Oates, heading selflessly out from the tent into the Antarctic wilderness. I am just going outside and may be some time. Poor, noble Peter Edwards, dying for the cause! Dying for the cause of things that were, in fact, already dead. It seemed such a waste.