1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This is another volume of the successful Best Short Stories Collection, a selection of masterpieces by authors from various nationalities and with very diverse themes, but sharing an enormous and possibly the most important literary quality: providing pleasure to the reader. In this e-book, you will have access to the Best Foreign Short Stories, a selection of memorable tales written by great masters of international literature such as James Joyce, Julio Cortázar, Borges, Horacio Quiroga, Edgar Allan Poe, and others. It is a unique and unmissable work!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 239

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

LeBooks Editions

THE WORLD’S BEST

SHORT STORIES

Contents

INTRODUCTION

ARABY

“A LA DERIVA” / ADRIFT

HOUSE TAKEN OVER

THE CONTINUITY OF PARKS

THE FEATHER PILLOW

FIRST SORROW

THE TELL-TALE HEART

THE BIRTH OF THE INFANTA

THE SELFISH GIANT

THE IMMORTAL

DAGON

THE NECKLACE

THE NINE BILLION NAMES OF GOD

THE HANDSOMEST DROWNED MAN IN THE WORLD

THE GIFT OF THE MAGI

TO BUILD A FIRE

A SOUND OF THUNDER

INTRODUCTION

Dear Reader,

Welcome to another volume of the Best Stories Collection, a selection of stories written in different eras by authors of various nationalities and with very diverse themes, but all sharing a significant literary quality and possibly the most important one: the ability to bring pleasure to the reader.

In this e-book, we present the Best Stories in the World, a selection of memorable stories written by great masters of short story literature from around the globe.

Enjoy an excellent read!

LeBooks Editora

ARABY

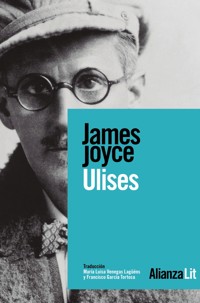

James Joyce

North Richmond Street being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers' School set the boys free. An uninhabited house of two storeys stood at the blind end, detached from its neighbors in a square ground The other houses of the street, conscious of decent lives within them, gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces.

The former tenant of our house, a priest, had died in the back drawing-room. Air, musty from having been long enclosed, hung in all the rooms and the waste room behind the kitchen was littered with old useless papers. Among these I found a few paper-covered books, the pages of which were curled and damp: The Abbot, by Walter Scott, The Devout Communnicant and The Memoirs of Vidocq. I liked the last best because its leaves were yellow. The wild garden behind the house contained a central apple-tree and a few straggling bushes under one of which I found the late tenant's rusty bicycle-pump. He had been a very charitable priest; in his will he had left all his money to institutions and the furniture of his house to his sister.

When the short days of winter came dusk fell before we had well eaten our dinners. When we met in the street the houses had grown somber. The space of sky above us was the color of ever-changing violet and towards it the lamps of the street lifted their feeble lanterns. The cold air stung us and we played till our bodies glowed. Our shouts echoed in the silent street. The career of our play brought us through the dark muddy lanes behind the houses where we ran the gauntlet of the rough tribes from the cottages, to the back doors of the dark dripping gardens where odors arose from the ashpits, to the dark odorous stables where a coachman smoothed and combed the horse or shook music from the buckled harness. When we returned to the street light from the kitchen windows had filled the areas. If my uncle was seen turning the corner we hid in the shadow until we had seen him safely housed. Or if Mangan's sister came out on the doorstep to call her brother in to his tea we watched her from our shadow peer up and down the street. We waited to see whether she would remain or go in and, if she remained, we left our shadow and walked up to Mangan's steps resignedly. She was waiting for us, her figure defined by the light from the half-opened door. Her brother always teased her before he obeyed and I stood by the railings looking at her. Her dress swung as she moved her body and the soft rope of her hair tossed from side to side.

Every morning I lay on the floor in the front parlor watching her door. The blind was pulled down to within an inch of the sash so that I could not be seen. When she came out on the doorstep my heart leaped. I ran to the hall, seized my books and followed her. I kept her brown figure always in my eye and, when we came near the point at which our ways diverged, I quickened my pace and passed her. This happened morning after morning. I had never spoken to her, except for a few casual words and yet her name was like a summons to all my foolish blood.

Her image accompanied me even in places the most hostile to romance. On Saturday evenings when my aunt went marketing, I had to go to carry some of the parcels. We walked through the flaring streets, jostled by drunken men and bargaining women, amid the curses of laborers, the shrill litanies of shop-boys who stood on guard by the barrels of pigs' cheeks, the nasal chanting of street-singers, who sang a come-all-you about O'Donovan Rossa, or a ballad about the troubles in our native land. These noises converged in a single sensation of life for me: I imagined that I bore my chalice safely through a throng of foes. Her name sprang to my lips at moments in strange prayers and praises which I myself did not understand. My eyes were often full of tears (I could not tell why) and at times a flood from my heart seemed to pour itself out into my bosom. I thought little of the future. I did not know whether I would ever speak to her or not or, if I spoke to her, how I could tell her of my confused adoration. But my body was like a harp and her words and gestures were like fingers running upon the wires.

One evening I went into the back drawing-room in which the priest had died. It was a dark rainy evening and there was no sound in the house. Through one of the broken panes I heard the rain impinge upon the earth, the fine incessant needles of water playing in the sodden beds. Some distant lamp or lighted window gleamed below me. I was thankful that I could see so little. All my senses seemed to desire to veil themselves and, feeling that I was about to slip from them, I pressed the palms of my hands together until they trembled, murmuring: "O love! O love!" many times.

At last she spoke to me. When she addressed the first words to me, I was so confused that I did not know what to answer. She asked me was I going to Araby. I forgot whether I answered yes or no. It would be a splendid bazaar, she said she would love to go.

"And why can't you?" I asked.

While she spoke she turned a silver bracelet round and round her wrist. She could not go, she said, because there would be a retreat that week in her convent. Her brother and two other boys were fighting for their caps and I was alone at the railings. She held one of the spikes, bowing her head towards me. The light from the lamp opposite our door caught the white curve of her neck, lit up her hair that rested there and, falling, lit up the hand upon the railing. It fell over one side of her dress and caught the white border of a petticoat, just visible as she stood at ease.

"It's well for you," she said.

"If I go," I said, "I will bring you something."

What innumerable follies laid waste my waking and sleeping thoughts after that evening! I wished to annihilate the tedious intervening days. I chafed against the work of school. At night in my bedroom and by day in the classroom her image came between me and the page I strove to read. The syllables of the word Araby were called to me through the silence in which my soul luxuriated and cast an Eastern enchantment over me. I asked for leave to go to the bazaar on Saturday night. My aunt was surprised and hoped it was not some Freemason affair. I answered few questions in class. I watched my master's face pass from amiability to sternness; he hoped I was not beginning to idle. I could not call my wandering thoughts together. I had hardly any patience with the serious work of life which, now that it stood between me and my desire, seemed to me child's play, ugly monotonous child's play.

On Saturday morning I reminded my uncle that I wished to go to the bazaar in the evening. He was fussing at the hallstand, looking for the hat-brush and answered me curtly:

"Yes, boy, I know."

As he was in the hall I could not go into the front parlor and lie at the window. I left the house in bad humor and walked slowly towards the school. The air was pitilessly raw and already my heart misgave me.

When I came home to dinner my uncle had not yet been home. Still it was early. I sat staring at the clock for some time and. when its ticking began to irritate me, I left the room. I mounted the staircase and gained the upper part of the house. The high cold empty gloomy rooms liberated me and I went from room to room singing. From the front window I saw my companions playing below in the street. Their cries reached me weakened and indistinct and, leaning my forehead against the cool glass, I looked over at the dark house where she lived. I may have stood there for an hour, seeing nothing but the brown-clad figure cast by my imagination, touched discreetly by the lamplight at the curved neck, at the hand upon the railings and at the border below the dress.

When I came downstairs again, I found Mrs. Mercer sitting at the fire. She was an old garrulous woman, a pawnbroker's widow, who collected used stamps for some pious purpose. I had to endure the gossip of the tea-table. The meal was prolonged beyond an hour and still my uncle did not come. Mrs. Mercer stood up to go: she was sorry she couldn't wait any longer, but it was after eight o'clock and she did not like to be out late as the night air was bad for her. When she had gone, I began to walk up and down the room, clenching my fists. My aunt said:

"I'm afraid you may put off your bazaar for this night of Our Lord."

At nine o'clock I heard my uncle's latchkey in the hall door. I heard him talking to himself and heard the hallstand rocking when it had received the weight of his overcoat. I could interpret these signs. When he was midway through his dinner I asked him to give me the money to go to the bazaar. He had forgotten.

"The people are in bed and after their first sleep now," he said.

I did not smile. My aunt said to him energetically:

"Can't you give him the money and let him go? You've kept him late enough as it is."

My uncle said he was very sorry he had forgotten. He said he believed in the old saying: "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy." He asked me where I was going and, when I had told him a second time, he asked me did I know The Arab's Farewell to his Steed. When I left the kitchen he was about to recite the opening lines of the piece to my aunt.

I held a florin tightly in my hand as I strode down Buckingham Street towards the station. The sight of the streets thronged with buyers and glaring with gas recalled to me the purpose of my journey. I took my seat in a third-class carriage of a deserted train. After an intolerable delay the train moved out of the station slowly. It crept onward among ruinous house and over the twinkling river. At Westland Row Station a crowd of people pressed to the carriage doors; but the porters moved them back, saying that it was a special train for the bazaar. I remained alone in the bare carriage. In a few minutes the train drew up beside an improvised wooden platform. I passed out on to the road and saw by the lighted dial of a clock that it was ten minutes to ten. In front of me was a large building which displayed the magical name.

I could not find any sixpenny entrance and, fearing that the bazaar would be closed, I passed in quickly through a turnstile, handing a shilling to a weary-looking man. I found myself in a big hall girdled at half its height by a gallery. Nearly all the stalls were closed and the greater part of the hall was in darkness. I recognized a silence like that which pervades a church after a service. I walked into the centre of the bazaar timidly. A few people were gathered about the stalls which were still open. Before a curtain, over which the words Cafe Chantant were written in colored lamps, two men were counting money on a salver. I listened to the fall of the coins.

Remembering with difficulty why I had come I went over to one of the stalls and examined porcelain vases and flowered tea- sets. At the door of the stall a young lady was talking and laughing with two young gentlemen. I remarked their English accents and listened vaguely to their conversation.

"O, I never said such a thing!"

"O, but you did!"

"O, but I didn't!"

"Didn't she say that?"

"Yes. I heard her."

"O, there's a ... fib!"

Observing me the young lady came over and asked me did I wish to buy anything. The tone of her voice was not encouraging; she seemed to have spoken to me out of a sense of duty. I looked humbly at the great jars that stood like eastern guards at either side of the dark entrance to the stall and murmured:

"No, thank you."

The young lady changed the position of one of the vases and went back to the two young men. They began to talk of the same subject. Once or twice the young lady glanced at me over her shoulder.

I lingered before her stall, though I knew my stay was useless, to make my interest in her wares seem the more real. Then I turned away slowly and walked down the middle of the bazaar. I allowed the two pennies to fall against the sixpence in my pocket. I heard a voice call from one end of the gallery that the light was out. The upper part of the hall was now completely dark.

Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.

THE END

“A LA DERIVA” / ADRIFT

Horacio Quiroga

The man stepped on something faintly soft and white and immediately he felt the bite on his foot. He jumped forward cursing and turned around to see the yaracacusú coiled around itself, ready for another attack.

The man cast a quick glance at his foot, where two droplets of blood were swelling arduously and drew his machete from his belt. The viper saw the threat and hid his head in the middle of his coiled spiral but the machete fell with the dull spine of the blade, separating the snake’s vertebrae.

The man knelt down to examine the bite, rubbed off the drops of blood and thought for a moment. A dull pain spread from the two violet punctures and began to invade his whole foot. Hurriedly, he tied his bandana around his ankle and hobbled along the trail towards his ranch.

The pain in his foot spread with a sensation of flesh bulging out from his taunt skin and suddenly — like thunder — pain irradiated out from the wound to the middle of his calf. He had difficulty moving his foot; a metallic dryness seized his throat, followed by a burning thirst, he let out another curse.

He finally arrived at his ranch and threw himself atop the wheel of his trepiche. The two violet dots now vanished in the monstrous swelling of his entire foot. His skin appeared to grow thin and tense to the point of bursting. He wanted to call to his woman but his voice broke in a coarse cry and was pulled back into his dry throat. The thirst devoured his voice “Dorotea!” He managed to throw out in a powerful cry. “Give me brandy!”

She ran over with a full glass that the man slurped up in three gulps. But he tasted nothing.

“I asked for brandy, not water.” He bellowed again. “Give me brandy.”

“But that is brandy, Paulino.” She protested, frightened.

“No, you gave me water! I want brandy!”

The woman ran back, returning with the demijohn bottle. The man drank glass after glass but felt nothing in his throat.

“Well, this is bad.” He murmured to himself looking at his foot, already bruised in a gangrenous luster. Over the bandana-knotted limb, flesh flowed like a monstrous blood sausage.

The blinding pain continued expanding in flashes of pain that reached his groin. The atrocious thirst in his throat seemed to grow warm as he breathed. When he attempted to sit up, he was seized by a fulminant urge to vomit; for half a minute he vomited with his head rested against the wooden wheel.

But the man did not want to die and made his way down to the coast where he climbed into his canoe. He sat in the stern and began to paddle towards the center of the Paraná. There, the current of the river, which runs six miles an hour in the vicinity of the Iguazu, would take him to Tacurú-Pucú in less than five hours.

The man, with somber energy, managed to arrive exactly in the middle of the river; but once there his sleeping hands dropped the paddle back into the canoe and after vomiting again — with blood this time — he crooked his head to look at the sun that had already began to set behind the high hills.

His whole leg, until the middle of his thigh, had already become a deformed and hard block bursting the stitching of his pants. The man cut the bandage and opened his pants with his knife; the underside of his leg overflowed in large swollen lurid blotches that throbbed in pain. The man thought that he could no longer reach Tacurú-Pucú by himself and decided to ask for help from his friend Alves, even though it had been a long while since they could be called friends.

The current of the river now rushed over to the Brazilian coast and the man easily docked his canoe. He dragged himself up the trail that ran up the slope; but after twenty meters, exhausted, he stayed there flat on his stomach.

“Alves!” He yelled with as much force as he could and he listened in vain. “Compadre Alves! Don’t deny me this favor.” He exclaimed again, lifting his head from the ground. In the silence of the jungle not even a whisper was heard. The man found the courage and strength to climb back into his canoe and the current, scooping him up again, took him rapidly adrift.

The Paraná ran down into the depths of an immense canyon whose walls, more than a hundred meters high, mournfully boxed in the river. From the river banks, lined with black spires of basalt, rose the forest, black as well. In front of him, behind the banks of the river, the eternal melancholy wall of the forest went on forever; in those depths the swirling river rushed in violent, incessant waves of muddy water. The landscape is unforgiving, yet in him reigned the silence of death. As dusk approached, without fail, the calm and somber beauty of the forest formed a unique majesty.

The sun had already gone down when the man, laying half conscious in the back of his canoe, came down with a violent chill. Suddenly and with astonishment, he slowly raised his heavy head — he felt better. His leg barely hurt, his thirst diminished and his chest, feeling freed, opened in a slow breath.

The venom began to leave him; he had no doubt. He felt fairly well and even though he did not have the energy to move his hand, he counted on the dewfall to recuperate him completely. He calculated that in less than three hours he would be in Tacurú-Pucú.

His condition improved and with it came a somnolence full of memories. He felt nothing in his thigh nor in his belly. Does his compadre Goana still live in Tacurú-Pucú? Perhaps he might also see his ex-employer and the buyer of all the men’s production, Mr. Dougald.

Would he arrive soon? The western sky opened into a golden screen and the river took on the same color. Onto the darkened Paraguayan coast, the mountain dropped over the river a faint freshness in penetrating aura of orange blossoms and wild honey. A pair of guacamayos flew high overhead, gliding silently towards Paraguay.

Down there, on the golden river, the canoe drifted rapidly, twisting itself around at times caught in the bubbling swirling water. The man that went with the river felt better with each passing moment and thought in the meanwhile about how long it had been since he last saw his old partner Dougald. Three years? No, not that long. Two years and nine months? Close. Eight and a half months? That was it, surely.

Suddenly the man felt frozen up to his chest. What could it be?

And his breathing as well…

He had met the man who bought Dougald’s lumber, Lorenzo Cubilla, on a holy Friday. Was it a Friday? Yes. Or maybe a Thursday.

The man slowly stretched his fingers.

“A Thursday…”

And he stopped breathing.

THE END

HOUSE TAKEN OVER

Julio Cortázar

We liked the house because, apart from its being old and spacious (in a day when old houses go down for a profitable auction of their construction materials), it kept the memories of great grandparents, our paternal grandfather, our parents and the whole of childhood.

Irene and I got used to staying in the house by ourselves, which was crazy, eight people could have lived in that place and not have gotten in each other’s way. We rose at seven in the morning and got the cleaning done and about eleven I left Irene to finish off whatever rooms and went to the kitchen. We lunched at noon precisely; then there was nothing left to do but a few dirty plates. It was pleasant to take lunch and commune with the great hollow, silent house and it was enough for us just to keep it clean. We ended up thinking, at times, that that was what had kept us from marrying. Irene turned down two suitors for no particular reason and Maria Esther went and died on me before we could manage to get engaged. We were easing into our forties with the unvoiced concept that the quiet, simple marriage of sister and brother was the indispensable end to a line established in this house by our grandparents. We would die here someday, obscure and distant cousins would inherit the place, have it torn down, sell the bricks and get rich on the building plot; or more justly and better yet, we would topple it ourselves before it was too late.

Irene never bothered anyone. Once the morning housework was finished, she spent the rest of the day on the sofa in her bedroom, knitting. I couldn’t tell you why she knitted so much; I think women knit when they discover that it’s a fat excuse to do nothing at all. But Irene was not like that, she always knitted necessities, sweaters for winter, socks for me, handy morning robes and bedjackets for herself. Sometimes she would do a jacket, then unravel it the next moment because there was something that didn’t please her; it was pleasant to see a pile of tangled wool in her knitting basket fighting a losing battle for a few hours to retain its shape. Saturdays I went downtown to buy wool; Irene had faith in my good taste, was pleased with the colors and never a skein had to be returned. I took advantage of these trips to make the rounds of the bookstores, uselessly asking if they had anything new in French literature. Nothing worthwhile had arrived in Argentina since 1939.

But it’s the house I want to talk about, the house and Irene, I’m not very important. I wonder what Irene would have done without her knitting. One can reread a book, but once a pullover is finished you can’t do it over again, it’s some kind of disgrace. One day I found that the drawer at the bottom of the chiffonier, replete with mothballs, was filled with shawls, white, green, lilac. Stacked amid a great smell of camphor. it was like a shop; I didn’t have the nerve to ask her what she planned to do with them. We didn’t have to earn our living, there was plenty coming in from the farms each month, even piling up. But Irene was only interested in the knitting and showed a wonderful dexterity and for me the hours slipped away watching her, her hands like silver sea-urchins, needles flashing and one or two knitting baskets on the floor, the balls of yarn jumping about. It was lovely.

How not to remember the layout of that house. The dinning room, a living room with tapestries, the library and three large bedrooms in the section most recessed, the one that faced toward Rodriguez Pena. Only a corridor with its massive oak door separated that part from the front wing, where there was a bath, the kitchen, our bedrooms and the hall. One entered the house through a vestibule with enameled tiles and a wrought-iron gated door opened onto the living room. You had to come in through the vestibule and open the gate to go into the living room; the doors to our bedrooms were on either side of this and opposite was the corridor leading to the back section; going down the passage, one swung open the oak door beyond which was the other part of the house; or just before the door, one could turn to the left and go down a narrower passageway which led to the kitchen and the bath. When the door was open, you became aware of the size of the house; when it was closed, you had the impression of an apartment, like the ones they build today, with barely enough room to move around in. Irene and I always lived in this part of the house and hardly ever went beyond the oak door except to do the cleaning. Incredible how much dust collected on the furniture. It may be Buenos Aires is a clean city, but she owes it to her population and nothing else. There’s too much dust in the air, the slightest breeze and it’s back on the marble console tops and in the diamond patterns of the tooled-leather desk set. It’s a lot of work to get it off with a feather duster; the motes rise and hang in the air and settle again a minute later on the pianos and the furniture.

I’ll always have a clear memory of it because it happened so simply and without fuss. Irene was knitting in her bedroom, it was eight at night and I suddenly decided to put the water up for mate. I went down the corridor as far as the oak door, which was ajar, then turned into the hall toward the kitchen, when I heard something in the library or the dining room. The sound came through muted and indistinct, a chair being knocked over onto the carpet or the muffled buzzing of a conversation. At the same time, or a second later, I heard it at the end of the passage which led from those two rooms toward the door. I hurled myself against the door before it was too late and shut it, leaned on it with the weight of my body; luckily, the key was on our side; moreover, I ran the great bolt into place, just to be safe. I went down to the kitchen, heated the kettle and when I got back with the tray of mate, I told Irene: “I had to shut the door to the passage. They’ve taken over the back part.”

She let her knitting fall and looked at me with her tired, serious eyes. “You’re sure?” I nodded.