Things I Wish I'd Known E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

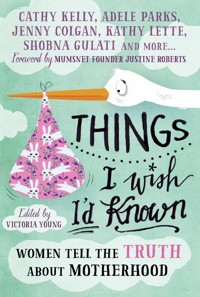

THE PERFECT GIFT FOR MOTHER'S DAY! Look at the front cover of any parenting book and what do you see? Glowing mothers-to-be, or pristine, beautifully-behaved children. But the reality is, your pregnancy might be a sweaty, moody rollercoaster, and your children will almost certainly spend the first few years of their lives covered in food, tears and worse. And the experience is no less magical for it. In this no-holds-barred collection of essays, prominent women authors, journalists and TV personalities explore the truth about becoming mothers. Covering topics from labour to the breastapo, twins to IVF, weaning to post-birth sex, and with writers including Cathy Kelly, Adele Parks, Kathy Lette and Lucy Porter (and many more), Things I Wish I'd Known is a reassuring, moving and often hilarious collection that will speak to mothers - and mothers-to-be - everywhere.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EDITED BY VICTORIA YOUNG Foreword by Justine Roberts

Contributors:

Adele Parks, Kathy Lette, Cathy Kelly, Bryony Gordon, Jenny Colgan, Christina Hopkinson, Anne Marie Scanlon, Emma Freud, Tiffanie Darke, Anna Moore, Esther Walker, Rachel Johnson, Lucy Porter, Afsaneh Knight, Clover Stroud, Nicci Gerard, Daisy Garnett, Alix Walker, Shobna Gulati

Published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

ISBN: 978-184831-836-6

Text copyright: Introduction © Victoria Young 2015, Foreword © Justine Roberts 2015, ‘Lost Property’ © Adele Parks 2015, ‘Lessons from Motherhood’ © Daisy Garnett 2015, ‘What to Expect When You Are Expecting and Then That Thing You Are Expecting Doesn’t Happen’ © Emma Freud 2015, ‘Single Plus One’ © Anne Marie Scanlon 2015, ‘Bite Me, Baby Experts!’ © Afsaneh Knight 2015, ‘The Breastfeeding Queen Who Never Was’ © Bryony Gordon 2015, ‘Working it Out’ © Tiffanie Darke 2015, ‘Motherhood: The Memo’ © Rachel Johnson 2015, ‘Babies Bounce’ © Jenny Colgan 2015, ‘Motherhood: 1,001 Nights’ © Nicci Gerard 2015, ‘The Life of Mammals’ © Cathy Kelly 2015, ‘Motherhood: The Eternal Imprint’ © Clover Stroud 2015, ‘Feed Me’ © Esther Walker 2015, ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ © Anna Moore 2015, ‘I Turned Parenting into a Test (and Scored an F)’ © Christina Hopkinson 2015, ‘Stiff Upper Labia’ © Kathy Lette 2015, ‘On Being an “Older Mum”’ © Lucy Porter 2015, ‘The Sleeping Babies Lie’ © Alix Walker 2015, ‘Mum. Mother. Mama.’ © Shobna Gulati 2015

The Authors have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The anecdotes in this book are written from personal experience, and are not intended to be a replacement for professional, expert or medical advice. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestion in this book.

Typeset in ITC Esprit by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For Tom and Max

Contents

Introduction

By Victoria Young

Foreword

By Justine Roberts, co-founder of Mumsnet

1. ‘Lost Property’

By Adele Parks

2. ‘Lessons from Motherhood’

By Daisy Garnett

3. ‘27 Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Had my First Child’

By Emma Freud

4. ‘Single Plus One’

By Anne Marie Scanlon

5. ‘Bite Me, Baby Experts’

By Afsaneh Knight

6. ‘The Breastfeeding Queen Who Never Was’

By Bryony Gordon

7. ‘Working it Out’

By Tiffanie Darke

8. ‘Motherhood: The Memo’

By Rachel Johnson

9. ‘Babies Bounce’

By Jenny Colgan

10. ‘Motherhood: 1,001 Nights’

By Nicci Gerard

11. ‘The Life of Mammals’

By Cathy Kelly

12. ‘Motherhood: The Eternal Imprint’

By Clover Stroud

13. ‘Feed Me’

By Esther Walker

14. ‘Stockholm Syndrome’

By Anna Moore

15. ‘I Turned Parenting into a Test (and Scored an F)’

By Christina Hopkinson

16. ‘Stiff Upper Labia’

By Kathy Lette

17. ‘On Being an “Older Mum”’

By Lucy Porter

18. ‘The Sleeping Babies Lie’

By Alix Walker

19. ‘Mum. Mother. Mama.’

By Shobna Gulati

Acknowledgements

Introduction

By Victoria Young

This is the book I wish had existed during my first few years of motherhood. If you’ve picked it up and are wondering whether it’s for you, or maybe for someone you know, the first thing to mention is that this is definitely not a ‘How To’ book. Rather, what you will find here is a collection of very different women sharing their unique, honest experience of motherhood: the highs and the lows, the funny bits and the sad bits, the good, the bad – and the not always pretty.

When I first started approaching women asking them if they wanted to write something about motherhood, the overwhelming response was ‘yes’ – they all had so much to say. But what really struck me as the book started coming together is that every single woman wanted to write about something different, whether it was navigating the world as a single mother of an unplanned baby, having a baby who thought sleep was for losers or how to nurture a relationship that has gone from being two to three. And that’s the thing about motherhood – there are as many ways to be a mother as there are women, and there is no one right way to do any of it. It’s just that when you are surrounded by all those ‘how-to’ books it’s easy to get confused and think that they are right, and you are wrong.

When I was first pregnant, four years ago, I spent hour upon endless hour thinking about my pregnancy and birth: buying a birthing pool, reading books about natural birth and assembling an ambient playlist in preparation for my home birth. But I gave barely any thought to what would happen if things didn’t quite pan out as I’d planned (like, say, if my home birth ended up being an emergency C-section). And although I was aware, in the most abstract way, that life as I knew it was about to change, the amount of time I spent dwelling on what life would actually be like once the baby had arrived was virtually nil. Or, rather, the time I spent thinking about it was coloured by, for example, my NCT class on breastfeeding, which consisted mainly of describing how, left to its own devices, my newborn would crawl up my tummy and ‘self-latch’.

In my case that information turned out to be so inaccurate as to be almost criminal, and, in retrospect, I wish I had asked for my money back. Unfortunately, I was too busy sitting on the sofa with each boob tethered to a milk-expressing flagon to do much of anything else for six months, because no matter how hard I tried – and BOY, did I try – breastfeeding didn’t really happen. But I really hung on in there with the expressing because at that stage I was still certain that denying your child breast milk was tantamount to child abuse, and that formula is the devil, obviously.1 I know lots of women take happily to breastfeeding like ducks to water, and that is a wonderful thing. I just wish I’d prepared for the possibility that not everyone does. The bottom line is that, despite reading many manuals about the theory of motherhood, somehow none of them even remotely prepared me for the reality of it.

The propaganda about motherhood starts in pregnancy, when people cross crowded rooms to stroke your bump and tell you, misty-eyed, how much they miss those early days and what a wonderful mother you will be. It’s lovely, in a way, how society conspires to treat pregnant women like fragile creatures who will be transported on a cloud to the flower-scented meadow of motherhood. But it’s not very helpful. For some reason it’s deemed cruel or distasteful or unfair to talk honestly to pregnant women about what lies ahead. Instead, people – and weirdly, it’s mostly other women – perpetuate a vague, fluffy idealisation of the truth that can be projected and spun out for nine months, which pregnant women, who know no better, get lulled into believing.

The problem with that, of course, is that when the baby actually comes along, the reality can be that much harder to deal with. Worse, it can leave women feeling they must be somehow lacking as a mother if they find it difficult. I know I felt that way. Even so, somehow the realities of motherhood often remain a hidden world, not talked about out loud.

But what I have slowly discovered is that everyone has a different experience and, often, it’s not straightforward. For every woman who has had an ecstatic birth followed by unparalleled joy and happiness at being a mother, there is someone for whom parenthood has had a difficult start because of colic (unexplained and relentless crying), a sleepless baby or because they are doing it solo – or just because of bewilderment at this new state of affairs: adjusting to having a third person in your relationship or to having a body that is battle-scarred and unrecognisable. Not to mention never having even close to enough sleep.

Personally, I probably had an unusually difficult start to motherhood – my baby was hospitalised for a week when he was ten days old because he was so dehydrated, after which he was tube-fed (and had nothing by mouth) for twelve weeks while doctors decided whether there was something wrong with his swallow. As it turned out there was not, but by the time the feeding tube came out, my son had lost the urge to breastfeed. So that was tough,2 and not at all what I’d expected those early days to be like.

But I found other aspects hard too. After paternity leave ended, my husband – with whom I had shared an equal partnership until that point – disappeared off to work every day while I stayed at home bouncing on my birthing ball to soothe the baby, then expressing milk, then feeding. Bouncing, pumping, feeding. Bouncing, pumping, feeding. There I sat, bouncing, all day, thinking: ‘Where has my life gone?’ and feeling a bit guilty that I wasn’t having the time of my life, as advertised throughout the duration of my pregnancy.

But when I mentioned I was finding it hard to anyone who asked how I was doing, I realised that was the wrong answer. Bizarrely, when you are learning how to do the most challenging new job you’ll probably ever do, you’re under pressure to pretend that everything’s going brilliantly.

Looking back, I wish I had been able to read more about other people’s actual experiences of motherhood, rather than how it ‘should’ be. Instead of reading manuals about what to do, I wish I’d read more about the myriad ways that things – from the birth to sleeping, to weaning, to toddlers, to teenagers and everything in between – actually do pan out. After all, there is nothing like knowing you are not alone.

The feeding thing turned out to be my big hurdle. Once we got that sorted, everything slowly started to get easier. Gradually, the angst subsided, I found my feet and I started to really enjoy it. Of course, there will be more challenges ahead, but now I am the mother of a funny, sweet and very loving little boy who has slowly lit up my world and filled it with more joy, fun and love than I had ever hoped I’d be allocated in life – and having a child is by far the best thing I have ever done.

If I could go back in time to talk to myself as I sat beflagoned and bewildered on the sofa, then I would probably say something along the lines of: ‘Don’t panic. Yes, your life feels like it has disappeared overnight, but it will come back – with bells on. Oh, he will eat like a trooper. And it doesn’t matter whether he breastfeeds or not. At some point he’ll start sleeping through the night. You’ll get the hang of it – really you will. He’s amazing. Nothing much else matters. All will be well. And you are doing a brilliant job.’

I very much hope this book will do something similar for you. Whether you are a seasoned mother or father, or just recently swept away on the tidal wave that is new parenthood, the aim is to offer some humour, hope and perspective. If nothing else, I hope you will take heart that you are not alone. But I hope the main thing this book makes you realise is that no one can do a better job than you.

Footnotes

1 My revised view, for what it is worth, is that formula really is NOT the devil. If you are having a hard time breastfeeding, please, please just give your baby a bottle of formula and give yourself a break.

2 Understatement!

Foreword

By Justine Roberts, co-founder of Mumsnet

In spite of having spent thirteen-plus years now being a parent and around twelve of those years running a parenting website, and in spite of having spent a fair bit of that time thinking about what it means to be a mother (when I wasn’t thinking about head lice, maths homework, search engine optimisation or poo), I still feel like you could fit my conclusions about this whole motherhood malarkey on the back of an envelope. And if you weeded out the bits that sound like the sappier type of Mother’s Day card, my words of wisdom would probably fit nicely on a postage stamp. And of course I have frequent days when my thirteen-year-old daughters send me letters detailing my many and various parenting sins … and usually they’ve got a point.

However, one thing I can say that hanging out on a website for mothers and reading their thousands of differing views has taught me is that there is no standard template for a good and effective mother. Among our regular users, there are some impressive teen mothers, a fair few who have had one or more children in their mid-forties, some inspiring mothers of children with special needs, a lot of full-time working mothers and full-time stay-at-home mothers, mothers of seven and mothers of one, single mothers, lesbian mothers, stepmothers and adoptive mothers. There are amazing mothers who cope with their own physical disabilities or mental illnesses. There are some who grind up carrots, others who get out jars and some who hand their babies a carrot baton. Women who do the school run in stilettos and a full face of slap and others who cruise through the day in their PJs. And the great thing about a website like Mumsnet is that often you don’t actually know any of these things about a person when they first start posting – so you only later find out that the fantastic advice about helping a child with school anxiety came to you courtesy of a mother still struggling with PND (or a dad). The internet is a great leveller, and it hits you when your prejudices are down. That anonymity can be a liberating thing, because while there may be many more ways to choose to be a mother now, it also feels like there is far more scrutiny of mothers and what they do. And maybe we all need to learn to put away stereotypes and take off what Mumsnetters would call our ‘judgey pants’.

As reproductive choices proliferate, it begins to seem that whatever choice we make (and how many of us have many real choices?) leaves us open to criticism. Having a child at all is selfish and ecologically irresponsible. Having a child too young is economically irresponsible. Having one too old is biologically irresponsible. And choosing not to have children is selfish and unnatural – the woman who decides not to be a mother often gets the worst press of all.

How and whether we choose to have children is only the first of many things for which mothers are held up to scrutiny. For women in the public eye, the relentless appraisal of body shape and size reaches new intensity during pregnancy and after childbirth. And you can’t get it right – the mother who gets her figure back within six weeks of the birth is clearly not spending enough time with her baby. The actress mother who looks flabby and tired at an awards ceremony is the subject of gleeful tabloid schadenfreude. That scrutiny filters down to the rest of us and how we feel about our postnatal bodies. And that’s just the beginning. It sometimes seems like barely a week goes by without the press reporting a new study about how some aspect of the way we look after our children – feeding, education, childcare – is fundamentally wrong and damaging. And a few months later another study demonstrates the opposite of the first study …

The fact that the most popular forum on Mumsnet is called ‘Am I being unreasonable?’ says much about the relentless self-analysis and need for validation that can go with the mothering territory. And truth be told, as well as a hell of a lot of advice and support and sharing of jokes, there is often a fair bit of judging that we’re all guilty of from time to time – of a mother on the bus whose eighteen-month-old is downing a bottle of Coke or feeding himself from a jar of baby food, or of toddlers let out in cold weather without hats. Yet at the heart of Mumsnet is a core philosophy which boils down to this: ‘There’s more than one way to skin a cat.’ And that’s just what this book proves.

Lost Property

By Adele Parks

Adele Parks is a bestselling author who has written fourteen novels, the latest of which is Spare Brides. She lives in London with her husband, Jim, and son, Conrad, who is thirteen years old.

The hardest thing I had to come to terms with when I had my son was that I suddenly became public property. I was no longer an independent woman; I was defined through someone else. I was not ‘Adele’; I was ‘a mother’. It’s funny, but marriage hadn’t clipped my wings in any noticeable way; we were a young, reasonably affluent London couple who still pretty much did what we liked when we liked, and I certainly wasn’t defined by myself or anyone else as ‘a wife’. However, the moment I became a mum – in fact as soon as I was pregnant – I suddenly transformed into a being that every member of society seemed to have a view on, worse still, a view they were all too willing to share.

I was shocked by the degree to which other people would offer up unsolicited opinions as to how I should raise my child. I remember giving my son a bottle of milk in a supermarket café (I know, hold the glamour!). As it happened, it was actually breast milk that I had expressed (because I didn’t always feel comfortable feeding in public), but a man in his forties came up to me and gave me a lecture about how breast was best and proceeded to tell me all the benefits I already was fully aware of. In effect, he was saying I was a bad mum for feeding in a way he disagreed with. This man didn’t know if I had mastitis or a child who hadn’t taken to the breast, or if I had simply decided to bottle-feed because, erm, it’s my baby. I didn’t bother to tell him it was breast milk, not because I didn’t feel I had to justify myself (I did feel that, I still do, that’s why I mention it now!). I just couldn’t justify myself because I was too angry. I simply told him if he ever had to get his boobs out in public to be a parent then he could have a view, but until then he couldn’t. He stormed off, outraged at my behaviour. OK, this wasn’t necessarily a moment I’m particularly proud of, but I think you’ll understand.

If the general public had confined their unsolicited advice to the parameters of how I should bring up my child, I might have managed to grin and bear it, to write off the interference as well-intentioned advice. However, it seemed to me that once I became a mum not only did everyone feel they could tell me how to do that exactly, but that they could pass comment on every aspect of my behaviour. Suddenly what I drank, ate, wore and said was scrutinised and judged. Received wisdom would have it that ‘Good Mums’ don’t drink, they eat well, they shouldn’t have time to look glamorous and they most certainly shouldn’t say ‘tits’ out loud in a supermarket.

Views from family members are to be expected and to some extent tolerated; families do involve themselves in one another’s lives, that’s their job. But everyone has a view about how I ought to look after my baby: other parents, people without children, strangers in the street, journalists, shopkeepers, butchers, bakers, candlestick makers! Furthermore, the public aren’t often that nice about mothers as a breed. It seemed to me that the word ‘mum’ was only ever attached to negative adjectives: ‘Pushy Mum’, ‘Overprotective Mum’, ‘Slummy Mummy’, ‘Frumpy Mum’. It seemed it was a lot easier to get it wrong than to get it right.

There is a strong consensus (too strong for me to dare ignore) that new mothers must ‘socialise’ their babies, the accepted meaning of which is to take them to pre-arranged (often expensive) playgroups. This naturally means that mothers have to spend time with other people they may not have all that much in common with – other than possession of a small baby – all of whom have opinions that they are keen to share. Quickly new motherhood can begin to feel like a competition. If Freddie is sleeping through the night and Millie isn’t, then the implication is that Millie’s mum is doing something wrong. If Azma manages to get out of nappies before Zac, then Zac’s mother is certainly to blame. Mums feel like failures on two counts: one) their child’s development is perceived to be behind that of other children; and two) it has to be her fault! The question ‘Does he eat avocados?’ suddenly seems like a judgement, not just a rather yuppie comment on my son’s digestive habits.

It’s only in hindsight that I can see that questions from other mothers about my son’s eating/sleeping/weeing/regurgitating habits were often more about insecurity than boastfulness. If only I’d known that at the time! Personally, I was plagued with a sense of ‘Do they [other mothers] know something I don’t?’ It was illogical then that I didn’t want them to tell me if they did! This is perhaps because of the inherited notion that women should all somehow instinctively know how to be mothers – no one wants to admit that their instincts might not be up to it.

As a new mother I had to come to terms with being public property – neighbours I’d never spoken to knocked on the door to get involved in my life, I had to join groups (I’m not a joiner, I’m actually quite a private person) and I had to answer to nursery teachers, midwives and health workers. I see the sense of these structures in our society and enormously respect the work done by these individuals, but I just hadn’t expected them to be there in my life. I’d had a vision that it would be just me, my husband and our baby. Naive, I know. I felt extremely connected with my baby and I adored him, but I was not always comfortable with the new people who entered my life. I sometimes found them to be a distraction from the real business of mothering. (The infernal, endless coffee mornings one is supposed to attend!) I found it really peculiar that I was plunged into society in this way. For a time I resented it enormously but, as time went on, something altered; I started to value it. Eventually I came to understand that these groups (organised or organic) which spring up in our society are there to support a mother. I changed. We do, however much we think we won’t.

My identity shifted. I’m pleased to report that I did not start wearing high-waisted jeans, bob my hair and suddenly find conversations about the texture of baby poo fascinating; I didn’t! However, I did start to understand the value of hanging around with other women who might know the Ofsted reports on the local nurseries and who would forgive me for not having the energy finish a sentence. Slowly I got to a place where I didn’t automatically dismiss or resent uninvited advice. Instead I sifted through it and often found invaluable nuggets of gold.

It took a lot of courage and reserve not to fall into any of the stereotypes of how the public imagine a mum ought to dress or what her interests are supposed to be. I made an effort to find the sort of women who celebrated the days I did have enough energy to put on lipstick and who gave me a high five if I managed to get my highlights done, rather than a disapproving glare. They are out there! I accepted that 99 per cent of the time the advice and information is well-intentioned, and the giver of the advice is just that – a giver. It was up to me to be adult enough to receive or reject it, but being resentful wasn’t helpful or sensible. I wasted a lot of time being too proud to accept help and assuming interference was a criticism, rather than a genuine desire to help, to be humane and human. Over time I felt increasingly integrated with society. Before I had a baby I believe I was lost property, and then I became public property. I wish I’d known that isn’t a bad thing.

1 My baby threw up a lot. (Actually he probably threw up the normal amount, but he certainly threw up more than an adult, which was my yardstick up until becoming a mum!) I changed his entire outfit after every sick-up, which was exhausting and unnecessary. I wish I’d known then that the world doesn’t stop if your baby has puke on his romper.

2 Ditto, your shoulder.

3 Competitive mothers are insecure. They are! If they have the time or need to compare your mothering skills with their own, or worse still, your baby with theirs, it’s because they are unsure, not because they are mean. Still, it doesn’t mean you have to hang around with them.

4 You don’t need to be a martyr to motherhood. I was. It’s probably not healthy.

5 It’s OK to admit you are knackered, confused, fed up or all three.

6 It’s OK to think your baby is the cleverest, prettiest, most alert baby ever, but only say as much to your partner and your mum. No one else agrees; if they pretend to agree then they are lovely friends, and you should hang on to them.

7 I wish I’d realised that my mother meant well when she was offering advice. She thinks I’m brilliant (I’m not, but see point six), and so she thinks she’s done a great job. She also thinks I’m doing a great job being a mum; she was not trying to frustrate me.

8 It goes on and on; motherhood is not just about being a mum to a newborn. You have lots of time to get it right, make some mistakes and then get it right again. My ‘baby’ is thirteen at the time of writing …

9 I wish I’d taken photos every single day because it flies past and I would have liked to catch and bottle up as much as I could.

10 Everything is going to be OK.

11 After having children you don’t just become a mother, you turn into your mother, too.

Lessons from Motherhood

By Daisy Garnett

Daisy Garnett lives in London with her husband, Nicholas, and their children, Rose, four, and Charlie Ray, two. She is a writer, freelance journalist and co-founder and editor of style and culture website A-Littlebird.com.

It’s hard for me to pinpoint when I became a mother. The timing is complicated for reasons I’ll explain, but I do remember precisely the moment I turned into the mother I didn’t want to be. It was the day my daughter, then two years old, called me a ‘silly bitch’. It came after a series of tantrums, a great many tears, a lot of hand-wringing, shouting and door-slamming, but it was delivered calmly and definitely along with this message: ‘This time, today, I have won.’

And she had, the silly bitch. ‘That’s the thing,’ a friend said to me when I asked him about his daughter, who was a year older than mine and always seemed impeccably behaved. He’d never raised his voice, ever, this parent, a father who worked long hours, and so wasn’t with his children day in and day out. ‘If you start shouting and behaving like them,’ he explained, ‘then they’ve won.’ They have, I agreed. Mine had.

I gave birth to my first child, a beautiful son, on the day he was due, which was 12 January 2009. He was perfect – isn’t every baby? – but, alas, he wasn’t alive. I was told that his heart wasn’t beating as I went into labour, which then proceeded, naturally, for twelve hours. When I was told that labour would continue I was amazed. I assumed that if your baby had died, then everything would stop, but no, you are told this news and then bam, another contraction arrives and then bam, another and then another, and you still feel your baby ripping through your body, so it’s hard to believe that anything has ended. How can his heart have stopped, I thought, when he’s pushing hard to get out into the world?

And so, at 3.12am on that January day, I became a mother, and for another twelve hours I held and cuddled and cradled my baby and stared into his tiny face and held his little hand and passed him over to his dad, so I could admire the two of them together, just like every other new mum does. Certainly, I had become a mother. Surely that was irrefutable? I had the stitches and the milk leaking out of my breasts and the still-pregnant-looking tummy. But I had to leave my baby in hospital, never to see him again, so I was also childless, which technically made me not a mother at all.

Rose arrived fourteen months later in March 2010 after a troubled pregnancy (entirely unrelated to Pip’s death), which saw me spending part of Christmas Eve and Christmas Day in hospital to receive steroid injections to lessen the risk of her dying should she be born dangerously prematurely, as was predicted. In fact, she arrived only three weeks early, and we left the hospital a couple of hours after she was born to become parents, proper.