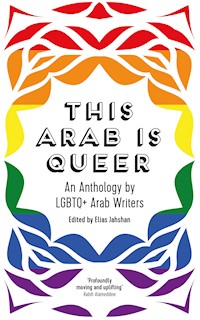

This Arab Is Queer E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This ground-breaking anthology features the compelling and courageous memoirs of eighteen queer Arab writers - some internationally bestselling, others using pseudonyms. Here, we find heart-warming connections and moments of celebration alongside essays exploring the challenges of being LGBTQ+ and Arab. From a military base in the Gulf to loving whispers caught between the bedsheets; and from touring overseas as a drag queen to a concert in Cairo where the rainbow flag was raised to a crowd of thousands, this collection celebrates the true colours of a vibrant Arab queer experience.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

THIS ARAB IS QUEER

Elias Jahshan (he/him) is a Palestinian-Lebanese-Australian journalist and writer. He is a former editor of Star Observer, Australia’s longest-running LGBTQ+ media outlet, and a former board member of the Arab Council Australia. His short memoir ‘Coming Out Palestinian’ was anthologised in Arab Australian Other: Stories on Race and Identity (Picador, 2019), and he has written freelance for outlets including The Guardian, SBS Voices, My Kali and The New Arab. Born and raised in western Sydney, he now lives in London.

THIS ARAB IS QUEER

An Anthology by LGBTQ+ Arab Writers

Edited by Elias Jahshan

SAQI

SAQI BOOKS

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Published 2022 by Saqi Books

Copyright © Elias Jahshan 2022

Elias Jahshan has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work.

Copyright for individual texts rests with the contributors.

Every reasonable effort has been made to obtain the permissions for copyright material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, however, the publishers will correct this in future editions.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 0 86356 478 9

eISBN 978 0 86356 975 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

ELIAS JAHSHAN

Introduction

MONA ELTAHAWY

The Decade of Saying All That I Could Not Say

SALEEM HADDAD

Return to Beirut

DIMA MIKHAYEL MATTA

This Text Is a Very Lonely Document

ZEYN JOUKHADAR

Catching the Light: Reclaiming Opera as a Trans Arab

AMROU AL-KADHI

You Made Me Your Monster

KHALID ABDEL-HADI

My Kali – Digitising a Queer Arab Future

DANNY RAMADAN

The Artist’s Portrait of a Marginalised Man

AHMED UMAR

Pilgrimage to Love

AMINA

An August, a September and My Mother

RAJA FARAH

The Bad Son

TANIA SAFI

Dating White People

AMNA ALI

My Intersectionality Was My Biggest Bully

HAMED SINNO

Trio

ANBARA SALAM

Unheld Conversations

ANONYMOUS

Trophy Hunters, White Saviours and Grindr

HASAN NAMIR

Dancing Like Sherihan

MADIAN AL JAZERAH

Then Came Hope

OMAR SAKR

Tweets to a Queer Arab Poet

Glossary

About the Contributors

ELIAS JAHSHAN

INTRODUCTION

In This Arab is Queer, eighteen writers share a personal story that is close to their hearts, one which they haven’t had the platform to write about before now. This ground-breaking collection subverts stereotypes and elevates voices identifying across the full LGBTQ+ spectrum – lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer and non-binary – and hailing from eleven Arab countries, both from the Gulf, Levant and North Africa, and from the diaspora (either as immigrants, children of immigrants, or recent refugees).

These writings assert our existence and agency as a community, and also celebrate our varied experiences. Here, readers will find stories of love and pride, heartbreak and empathy, courage and humour. This is a space where the microphone is entirely the writers’ own. To the best of my knowledge, it is the first collection of its kind.

Many readers will know that most Arab countries criminalise homosexuality. The level of enforcement varies from country to country. In Egypt, recent police crackdowns carried out on queer people have resulted in scores being imprisoned, and sometimes tortured. In Lebanon, laws against homosexuality are not generally enforced, allowing for a visible queer community to thrive in the capital Beirut. In a few countries – namely Jordan and Palestine (except for the Gaza Strip) – homosexuality is not a crime, though laws protecting the community from discrimination are virtually non-existent. In a handful of other countries – Saudi Arabia, Yemen and in some cases in the UAE and Iraq – homosexuality is punishable by death.

It is interesting to note that many of these restrictions stem from inherited European colonial laws that were informed by a Christian understanding of morality. When the West talks about homophobia in the Arab world or among global diasporic communities, the focus is on how Islam or traditional Arab attitudes are at the root of hostility toward LGBTQ+ Arabs, which is an essentialist and simplistic approach. On the flipside, patriarchal norms are deeply embedded in Arab culture and is an important reason for the rampant discrimination, criminalisation and deep cultural stigma of queer people.

As a gay Arab writer and journalist, and in my stint as editor of Australia’s longest-running queer media outlet, Star Observer, I have observed that Western media outlets often focus on sensationalist news stories. Well-known examples include gay men being thrown from rooftops during Daesh’s reign of terror in Syria and Iraq, or homophobic attacks in Morocco after Instagram influencer Sofia Taloni told her followers to use gay dating apps to locate and publicly out gay people. The issue isn’t that these events are covered of course; it’s that the media seemingly only pay attention to negative stories, and rarely engage with Arab voices directly.

A rising number of LGBTQ+ Arabs are stepping forward to tell stories about queer life, however. Their stories are complex and go beyond the usual narratives of state-sanctioned discrimination or family homophobia and transphobia.

While queer Arab writing in the Arabic language is scarce, mostly due to government-enforced bans and censorship, in the West it is not a new phenomenon. Since the 1990s, we have been gifted with wonderful works written by and about queer Arabs. To name a few: the trailblazing Koolaids: The Art of War (1998) by Rabih Alameddine; Abdellah Taïa’s Salvation Army (2006); Saleem Haddad’s Guapa (2016); Danny Ramadan’s The Clothesline Swing (2017); Leila Marshy’s The Philistine (2018); Amrou Al-Kadhi’s Life as a Unicorn (2019); and Zeyn Joukhadar’s The Thirty Names of Night (2020) – or more recent works by Zeina Arafat (You Exist Too Much, 2021), Randa Jarrar (Love Is an Ex-Country, 2021), Omar Sakr (Son of Sin, 2022) and Fatima Daas (The Last One, 2022). Such voices may not always be visible in mainstream outlets, but they are becoming more prolific.

LGBTQ+ Arabs are often asked how it is possible to be queer in our culture. We are expected to explain the ways in which homophobia can make our coming-out journeys a challenge, should we choose to embark on that journey. The question implies that Arabs do not have the capacity to be progressive. It also limits our ability to tell our stories on our own terms. In This Arab is Queer, we reclaim the narrative and show how we can comfortably be both.

Certain themes that are central to many lived experiences for queer Arabs emerge in this collection, such as coming-out stories, how it feels to be shoe-horned because of your identity, what it means to be unseen, or to have seen too much. The importance of friends, family and community is understood more keenly when read in tandem with essays on displacement and loneliness, such as in Dima Mikhayel Matta’s This Text Is a Very Lonely Document, which articulates solitude and how it plays out with the journey as a non-binary person from Lebanon, with such eloquence; or Madian Al Jazerah’s piece Then Came Hope, which explores the particular heartache of a gay Palestinian man who has been made diasporic three times over – from Palestine to Kuwait, then onto Jordan and the US. In The Artist’s Portrait of a Marginalised Man, Danny Ramadan looks at how his cultural identity and sexuality play out in his writing, exploring the fraught path of a marginalised writer who is obliged to represent an entire community in their work, while being denied the artistic licence to centre on characters whose lives are not carbon copies of the writer’s own. Together, these pieces paint a portrait of what queerness across the Middle East and the diaspora looks and feels like today. In fact, it’s true to say every text in This Arab is Queer delivers on this.

While some of the writers whose work is published in this collection live in the Middle East, some are now living elsewhere. As a result, this book travels across time and space; from Baghdad to Vancouver, Lisbon, Dubai, Belgrade, Mecca, New York – and across locales, touching down in hospitals, schools, opera halls, suburban Sydney homes, Cairene concert arenas, Cypriot bookshops and bedrooms, balconies, literature festivals, the backstreet ruins of Beirut’s port silos and the lush surrounds of the Blue Nile. Many pieces straddle more than one place, such as Ahmed Umar’s essay Pilgrimage to Love, which revisits his formative years in Saudi Arabia and Sudan, offering readers an intimate and unique insight into what it was like growing up as a queer person in the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa.

Some essays, such as Amina (pseudonym)’s An August, a September and My Mother deal with events whose fallout was felt the world over; in this case, Amina offers a rare, on-the-ground story around Sarah Hegazy’s tragic death and how it impacted her as a member of Egypt’s queer community. Intertwining the personal with a wider social context, Amina offers readers a sense of solidarity and hope, as well as paying homage to Sarah. Other writers focus on experiences behind closed doors, on private affairs of the family. Anbara Salam considers the silence around taboo subjects in Arab families in Unheld Conversations and how our sexualities can be the elephant in the room at family gatherings. In Dancing Like Sherihan, Hasan Namir writes about his multiple coming-out journeys as a gay Iraqi, and the love and loyalty of his sisters and newfound sister-in-law, who offers to be surrogate for Hasan and his husband’s unborn child.

Many of the writers express their complex, varied relationships with their parents, and how the importance of family is drummed into our psyche from a young age. In You Made Me Your Monster, Amrou Al-Kadhi articulates how Arab children are seen as an extension of their parents – not individuals with their own agency – and reveals the complicated family dynamics this causes. At the same time, the importance of family, and the instinctive yearning for family approval and acceptance, is apparent throughout. Perhaps nowhere is this more so than in Raja Farah’s The Bad Son, which follows a dutiful son who is the primary, yet somewhat resentful, caregiver for an aggressive, hypermasculine father. Unsurprisingly, the son’s sacrifices for his family have a profound impact on his dating life.

Rebellion against one’s parents, and even whole culture, is carried out in both private and public spheres. Indeed, many of these contributors are no strangers to speaking out publicly. In My Kali: Digitising a Queer Arab Future, Khalid Abdel-Hadi details the trials he faced as the founder and editor in chief of My Kali, the Arab world’s longest-running queer media outlet, and how he and his sexuality were made public by the Jordanian media and government. Speaking out goes hand-in-hand with being seen and heard, considered by Hamed Sinno’s a meditation on the power of the voice in Trio. Sinno highlights the role their voice plays in transgressing social norms and customs in public. From contemporary to classical music: Zeyn Joukhadar explores how his journey as a trans man saw him fall in love with opera all over again in Catching the Light: Reclaiming Opera as a Trans Arab. Zeyn also details his experience of how class boundaries intersected with trans identity on his journey, through his examination of notable (orientalist) operatic works and spaces. Many of these pieces demonstrate the perceived transgressive existence of queer Arabs, taking pride in a community that is not afraid to push the boundaries, and showing that these transgressions are needed for us to evolve and progress.

All of these pieces interweave the personal and the political – how could they not? Some writers tackle the spaces where politics and sexuality meet head on. Mona Eltahawy returns to the 2011 revolution in Egypt, as Hosni Mubarak was ousted from office, in her piece The Decade of Saying All That I Could Not Say. She shows how a traumatising event around this time served as an awakening of sorts for her both as a feminist and as a queer, polyamorous woman who came out in her forties. Amna Ali’s My Intersectionality Was My Biggest Bully bravely articulates the struggles of growing up queer, Arab and Black in a society that denies its own racism and is comfortably, openly homophobic. In a critically important piece, Amna goes into detail about her upbringing in the Gulf, while, on the other side of the world, Tania Safi’s Dating White People looks into how she internalised racism within the lesbian community in Australia to the point where her own brother questioned if she herself was a white supremacist.

Of course, there couldn’t be a collection that centred on sexuality without sex, complete with all its stigma, shame and glory. In Pilgrimage to Love, Ahmed Umar recalls his fear after a religious teacher shared his understanding of God’s wrath against homosexuals and the suitable punishments that should be meted out to those practising same-sex relations; while Madian Al Jazerah’s Then Came Hope recounts with both sadness and humour his mother’s graphic, blind assurance that only the ‘bottom’ is gay in a male same-sex coupling. Sometimes sex is inextricably linked with humour, a dash of racism aside. One contributor, who chooses to remain anonymous, encapsulates this in Trophy Hunters, White Saviours and Grindr, where they detail some awkward moments from their time dating while living in the US.

The taboos around premarital sex intensify the desire of the experience for those who have to postpone, plan and conceal sex. Sex positivity is sorely needed in our Arab community, and it is found here, where the joy and importance of sex and of self-discovery coincide. Omar Sakr’s concluding piece Tweets to a Queer Arab Poet is a poetic compilation of tweets in conversation with Adonis, that serves to inspire and encourage queer Arabs to celebrate who we are and to explore our desires.

Sometimes, celebration and mourning become one. Saleem Haddad’s piece Return to Beirut laments the loss of his homeland and what it represents in the wake of the Beirut port explosion, while also mourning a romance he briefly rekindles. But at the same time Haddad shows the agency we have when we put down roots in a place and at a time of our choosing.

Not every piece speaks directly to queer Arab identity; but where they do, as many questions are raised as answers suggested. This is because the plurality of experiences shows without a doubt that one size doesn’t fit all – there is no set formula for life as a queer Arab. Yet together, this collection inspires readers to imagine a bright future for the Arab queer community and for the possibility of love in spite of the stigma we face.

My hope is that This Arab is Queer encourages a safe space for conversation and validation, as well as a changing climate among LGBTQ+ communities. If this book becomes the first of many that centres on queer Arab experiences, and encourages broader engagement with queer Arab writing, it will have fulfilled its mission. I look forward to discovering the plethora of unique stories that are waiting to be told.

MONA ELTAHAWY

THE DECADE OF SAYING ALL THAT I COULD NOT SAY

I am writing this almost exactly ten years after I died.

I am able to write this because I died ten years ago.

The Mona I used to be died on 24 November 2011, on a street called Mohamed Mahmoud, near Tahrir Square, Cairo. Riot police beat her, broke her left arm and right hand, sexually assaulted her and then dragged her to their supervising officer who threatened to have her gang-raped by more of his men. She was detained incommunicado for six hours by the Interior Ministry and another six by military intelligence who blindfolded and interrogated her.

When she was finally released, she bequeathed me a new life and the things she could not say. The past ten years have been the Decade of Saying All that I Could Not Say.

Like nesting dolls – where one doll opens to reveal an identical doll fitting inside it, which then opens up to reveal another identical doll inside it, and so on – every time I spoke a secret I found a more intense version of myself which in turn demanded I say more of what I could not say, and so on, until I got to the core of my silence.

I wrote about taking off my hijab, which I wore for nine years. I wrote about being raised to wait until marriage before I had sex. I wrote some more about the latter, to amend it and say that I was raised to wait until marriage before I had sex with another person – and I obeyed – although I’d been having sex with myself since I was eleven years old. (And thank all the goddesses for that, or else I would have lost my fucking mind waiting for that Egyptian, Muslim cisgender dick to make a decent woman out of me.)

One broken silence led to another silence nestled within it, which led to another, and so on.

I wrote about the two abortions I had. I wrote about menopause and how it was affecting my sex drive. I was on a roll. Shame had nothing on me. When you are shameless you cannot be shamed.

What more? What else? What was that smallest doll nesting inside all these silences I’d smashed?

It took Ireland and Bosnia to force a reckoning with my nesting dolls of secrets.

Of all the countries I have travelled to for work in the Western world, I have always felt most understood in Ireland. Unlike many other European countries which prefer to deny and distance themselves from talking about where I am from – Egypt and the surrounding region – and say, ‘It’s shit over there’, Ireland understood: ‘It’s shit over here too’. The stranglehold of the Catholic Church on everything from politics to education to geopolitics fostered understanding and empathy whenever I spoke there.

In 2015, Ireland became the first country to hold a referendum on marriage equality. The reckoning that such a referendum was required inspired Ursula Halligan, one of Ireland’s most high-profile journalists, to come out at the age of fifty-four. (At the time of writing, I am also fifty-four). She wrote poignantly about a secret she thought she would take to her grave.

‘I was a good Catholic girl, growing up in 1970s Ireland where homosexuality was an evil perversion,’1 she wrote. ‘It was never openly talked about, but I knew it was the worst thing on the face of the earth. So when I fell in love with a girl in my class in school, I was terrified.’ Halligan’s words gave me whiplash.

When I was sixteen years old, I was a good Muslim girl, growing up in Saudi Arabia where homosexuality was an evil perversion. I too fell in love with a girl in my class. But unlike Halligan – and this I now realise had been my denial and distance – I was in love with a girl and a boy at the same time and thought everyone else was too. I did not have a word for it, and I could not explore it beyond feeling jealous when the girl I was in love with told me she was in love with a boy and crestfallen when she did not say I, too, was an object of her love. It would take another three decades until I kissed a woman. But, tellingly, it would also take another decade until I kissed a man.

At around the age of seventeen, I began having nightmares that I had married the wrong man. Even when, at the age of twenty-one, I left gender-segregated Saudi Arabia for the more relaxed Egypt, my country of birth, I wanted very little to do with men. I was that good Muslim girl who was waiting for marriage and, much like Halligan, poured myself into work.

When I read Halligan’s coming-out essay, I marvelled at the almost identical teenage love for a girl and I wondered how our journalism careers had helped us hide. I knew that I, at least, was hiding in plain sight.

Was I brave? Of course I was: I wrote articles that exposed the human rights violations of a regime that tapped my phone, had me followed, summoned me for interrogation at State Security several times, threatened to imprison me, and eventually made good on its threats that night on Mohamed Mahmoud Street in November 2011.

Was I brave? Of course I was not. I could not say, for the longest time, that I desired men and women. How could I when, for the longest time, men alone were off limits. How was I to figure out what I desired when desire for anyone was off limits?

Still, I hid in plain sight.

Before I left Egypt for the United States in 2000, my feminism had focused solely on misogyny, which I understood was protected and enabled by patriarchy. I knew there was an LGBTQ+ community in Egypt, as there is in all countries. When I attended a conference in 2004 for LGBTQ+ Muslims organised by al-Fatiha, one of the first ever organisations of its kind, I began to combine feminism with the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. Our enemy was the same: the patriarchy, specifically a heteronormative patriarchy that privileged heterosexual relationships. Several more Muslim LGBTQ+ organisations exist today.

Soon after, I began to openly support queer people and issues. Some assumed me to be a good ally and asked me to blurb their books or began to follow me on social media, knowing they had an empathic and enthusiastic supporter. Others would slide into my DMs where they would be met with a kind and friendly, ‘I am flattered but I am not gay.’

When I travelled to Beirut in 2009, I spent my first evening at the kind of event I never imagined I could attend in the Middle East at the time. In a theatre on Hamra Street, two women on stage who openly identified as lesbian read in Arabic and English from a book being released that night called Bareed Mista3jil (‘Express Mail’), a collection of forty-one personal, anonymous oral narratives by lesbian, bisexual, queer and questioning women, and the trans community in Lebanon. The stories cover women from across the country – rural and urban, and across faith and sectarian lines. Some are about the difficulty or impossibility of coming out, the threats to life, the decision to emigrate only to find that homophobia is replaced in western countries by anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia.

‘A lot more has been said about male homosexuality than female sexuality. This comes as no surprise in a patriarchal society where women’s issues are often dismissed,’2 the editors of Bareed Mista3jil wrote in their introduction. ‘And sexuality, because it touches on reclaiming our bodies and demanding the right to desire and pleasure, is the ultimate taboo of women’s issues. We have published this book in order to introduce Lebanese society to the real stories of real people whose voices have gone unheard for hundreds of years. They live among us, although invisible to us, in our families, in our schools, our workplaces and our neighbourhoods. Their sexualities have been mocked, dismissed, denied, oppressed, distorted and forced into hiding.’

When a friend of mine in Cairo came out to me as a lesbian she also explained why, despite her long activism against the Mubarak regime, despite the ways she had risked her life and career as part of that activism, she was not ready to come out to her family nor publicly. I told her I supported her with whatever she felt was best for her and that I was honoured she trusted me with her confidence. As a sexually active woman, she was challenging many of our country’s most sensitive taboos already, but with the added risk, complication and censure of having sex with women. It was multi-layered silencing and being rendered invisible.

Yet I was still not yet ready to have that reckoning with myself.

My friend’s fear was a reminder that the personal is often more dangerous and harder to say than the political. It was a reminder of why I was able to confront the Egyptian regime during all those years of journalism, and yet it took me a decade after it killed Old Mona on Mohamed Mahmoud Street for New Mona to speak.

When I was twenty-eight, I became – finally – sexually intimate with a person other than myself. That sounds like an awful lot of words to say, ‘lost my virginity’ or, ‘had sex for the first time’ but I lost nothing – it was fucking wonderful – as I had already been masturbating and enjoying the orgasms I gave myself. To say ‘had sex for the first time’ sounds like Christopher Columbus ‘discovering’ a country that existed long before he set sail. I have determined to retire those phrases I used to use once and for all.

I chose the person I was now having more orgasms with – a man I asked out and with whom I declared a truce in my war against femininity. When Y and I had penis-to-vagina sex – a phrase that did not exist in my lexicon in 1996 – I stopped reading the Quran. I could not stand reading the word ‘fornicators’ repeated again and again. And I started growing my hair. I am still trying to figure out why.

Short hair had, for years, been central to my identity. I am told that, when I was ten days old, my paternal grandmother had my ears pierced. This is a very common practice in Egypt, where gold stud earrings are a popular gift for baby girls. That same grandmother was a teacher and a smoker – in a society where smoking is considered a male privilege. When my mother complained to her that I cried every time she tried to detangle my hair after washing it, my grandmother’s advice was, ‘Just cut her hair short.’ So, from the age of three or so, my mother kept my hair very short.

When I moved to London in 1975, at seven, the first time I went downstairs to play with the other children, they asked me, in order: ‘What’s your name? Are you a boy or a girl?’ My English wasn’t so good and I ran back home.

None of the questions was asked with malice, but the last question was indicative of an expectation British society had for markers of ‘boy’ and ‘girl’. My neighbours didn’t see those markers in my appearance and they were confused.

But it was said with malice, when I was thirteen and in Cairo, by the guy who told his friend, ‘That girl used to be a boy and they gave her a sex change.’

What does a girl look like? Who taught me to be a girl?

When I started growing out my hair after sex with Y, was I performing what I thought a sexually active, heterosexual woman looked like? Was I comfortable with the trappings of femininity now that I was older? When I had been younger, had I associated it with weakness? Were those years in hijab responsible for the power I had amassed?

When I removed my hijab aged twenty-five, I had worn it for nine years. On the day I stopped wearing it, I arranged for what I considered an intentionally ugly haircut. I did not want to be beautiful. I did not want my de-hijabing to be ascribed to a need for the male gaze’s approval. I wanted nothing to do with that gaze.

I was unsure if it was the gaze – that infamous eye of the beholder – or the beholder himself that I did not like.

Was sexual intimacy with Y giving birth to a new iteration of me? When did I start believing that nonsense about the ‘magic penis’, that heteropatriarchal nonsense that claims that being penetrated by a penis changes everything?

Adrienne Rich, a feminist and literary icon, defined compulsory heterosexuality as the ways by which a patriarchal and heteronormative world socialised women into heterosexuality – and I was taught a specifically Egyptian and Muslim version of it. I was raised to wait until I married a Muslim, Egyptian man to have sex. And for the longest time – too long – I obeyed. I could not find anyone I wanted to marry – or, more truthfully, I did not want to find anyone I wanted to marry. I became fed up with waiting and fed up with wondering, ‘What if it did not have to be a man?’

In 2013 I finally kissed a woman. I had always assumed that, when I had a threesome, it would be between two men and me. But it turned out to be with a man whom I was seeing and a woman we invited to join us. It was also me who reached out and kissed her. And when the man left the room to use the bathroom, it was me who reached out for her once again. Still, I used no label and did not further explore my attraction to women.

In 2015, when I was getting to know the man who is now my Beloved and anchor partner, he told me in one of our earliest email exchanges that he was bisexual. I replied that I was polyamorous. I knew by then that monogamy was not for me, but I was still not ready to say that I, too, was bisexual. Learning how he explored and then acknowledged his sexuality has been a tremendous help, one that I credit with the progress I’ve made in shattering this final nesting doll of silence I’ve held onto for so long. While I was not ready to say I was bisexual, I did start to call myself queer – I considered my polyamory to be a form of rebellion and resistance to heteronormativity.

When I finally had intercourse with Y, I was forced to deal with the guilt that ensued from knowing that I had broken a once-unquestioned taboo. I confronted that guilt by fucking it out of my system. I hated that I was still held hostage by that guilt. I hated how the patriarchy dictates how and when a woman can express herself sexually. ‘I own my body’ was a mantra that was long in the making, and I earned the right to say it out loud on a stage as I do now. I insist on saying that I fucked the guilt out of my system because being brazen and shameless are not powers I am supposed to wield so easily. But I have seized them for myself and I wield them joyfully.

When I talk about sex and my own journey, I talk openly and with joy about lust, pleasure and desire, because they are ‘sins’ for those of us dispossessed by patriarchy of the right to enjoy our body when and how we want. It is especially important for me to talk about joy, pleasure, lust and desire because I survived state-sanctioned sexual assault in Egypt in November 2011, as well as the daily onslaughts that are sanctioned by a society that does nothing to stop them, because public space is a privilege that the patriarchy awards to men. It is especially the state-sanctioned sexual assault that I highlight when I talk about the power of seizing and wielding brazenness and shamelessness.

Every woman must deal with surviving sexual assault in the way that she best finds healing. When I talk about my healing, I insist that the conversation does not end with my assault but rather continues into how part of my healing was to have a lot of consensual and joyful sex. It is the antithesis of the assault I was subjected to and the gang rape I was threatened with. I enjoyed my body. It was important for me to find joy again through pleasure and desire.

Over the years I have also spoken more openly about my move away from monogamy. One of the reasons I waited so long to have sex was that I was bound by patriarchal dictates about purity and modesty that unfairly burden women and girls. Once I smashed those dictates and fucked the guilt out of my system, I was determined to be free. I wanted nothing to do with those dictates that privilege male dominance.

I had not come across June Jordan’s essay ‘A New Politics of Sexuality’3