Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

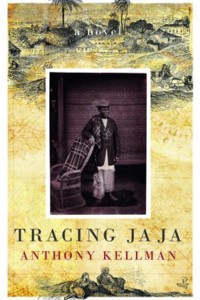

Anthony Kellman has created a warmly human work of historical fiction. He locates it between the trace of a satirical folk song, ridiculing the old African king's affair with his Barbadian servant, and the official records of the illegal kidnapping and exile to the Caribbean of Jubo Jubogha, the King of Opobo, who stood in the way of British imperial interests in the palm-oil rich region of the Niger delta. The novel focuses on the last four months of Jaja's life and the ironies of his position in Barbados where Whites dominated all aspects of life and race prejudice was nakedly expressed, but where many Black Barbadians were piqued to discover the presence of an African king amongst them. At the heart of the novel is an entirely human drama in which, though his relationship with young Becka brings new life to his battered body and spirit, and the Barbadian landscape lifts his despair, the king never loses his sense of the injustice done to him or gives up on his urgent desire to return home. Anthony Kellman writes with subtle psychological insights into a relationship that crosses ages and cultures, and with a poet's perception of the natural beauties of his own island.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANTHONY KELLMAN

TRACING JAJA

First published in Great Britain in 2016

This ebook edition published 2020

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King's Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

Copyright © 2016, 2020 Anthony Kellman

ISBN 9781845232993(Print)

ISBN 9781845235048(Epub)

ISBN 9781845235055 (Mobi)

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission

CHAPTER ONE

The king arrived on the first day of March, two weeks after an invasion of rats on a St. George plantation prompted an early start to cutting the canes. The rodent assault would slow-up cropping, extend it into the rainy season, affect the sucrose content, and disappoint the Queen.

The Pylades, the steam boat on which the king arrived, sat for a time in Carlisle Bay, but he did not see the island as it slowly grew from an ocean-surrounded speck to an undulating mass of greenness, hills speckled with white houses, royal and coconut palms, and the shingled roofs of the city’s coral-stone buildings. He saw none of this because of the ailments that made bed-rest a constant feature of his journey.

He knew he’d arrived only when he heard a loud knocking on the cabin door.

‘We’re here,’ the officer said. ‘Come.’

King Jaja rose slowly from the bed, steadying himself on the end of the frame. The officer stepped back into the passageway leaving the door slightly ajar. Jaja put on his black leather sandals and limped over to the peg for his admiral’s uniform. Sixteen years earlier, Queen Victoria’s consul had presented him with the uniform and an inscribed sword in appreciation of his military assistance during the Ashanti War. He’d rarely worn the uniform but had kept it immaculately clean. As he dressed, he scratched at his body, as if some sorrow lay under his skin that flamed like a burning hut. He seemed to bear a defeat that was more than individual.

The passengers on The Pylades now began to board smaller boats to take them to Bridgetown Wharf. When the boat carrying Jaja pulled up at the wharf-side, the crowd lining the waterfront called out and cheered as they stared at the garb he wore. None had seen a black man dressed like this before. They were filled with questions, bright with pride and an inchoate sense that they were witnessing something about their origins, somewhat tarnished but lambent like the morning light flickering on the glazed wharf water. Their voices merged with the sounds of the sea, dying away from the king’s hearing only when his carriage reached the city limit. Instead, the horses’s hoofs were constant exclamations in his mind, which itched and flared like his body.

Half an hour later, the vehicle arrived at the gate of the Governor’s house. The police officer standing in the white guard shed waved the carriage through. One of the guards got out and walked to the front of the house, to the verandah ringed with brilliant red hibiscus. He rapped the brass knocker on the white door that swung open almost at once. The Governor was expecting him.

The guard said, ‘He attracted much attention, Sir. Especially among the common people. They watched his every movement, crowded about the carriage, much to our discomfort.’

Governor Sendall had assumed personal oversight for all the details of the king’s detention and had arranged the Sunday dawn arrival to avoid the risk of the public spectacle that a Saturday arrival would involve. The authorities had made that mistake in St. Vincent where Jaja had been detained for nearly three years before his transfer to Barbados. He’d arrived in Kingstown Bay around noon when the markets were crowded with people. When news of his arrival reached them, they’d abandoned their buying or selling and flocked to get a glimpse of the king. Because of the pandemonium, the authorities had been forced to keep Jaja and his son Sunday on board the Icarus for another day.

The Governor looked away from the guard and out across the gardens, his glance settling on a row of mahoganies. Even with the precautions taken, Jaja’s coming had evidently caught the attention of Bridgetown’s rabble and word had spread.

‘How is he?’

The guard withdrew a thick string-bound document from the leather bag and handed it to the Governor. ‘Documents from St. Vincent, Sir. Including reports on his health.’

When Sendall finished scanning the documents, creases appeared on his brow. He pursed his lips and then released them. ‘You’d better get him settled in at Two Mile Hill. When he’s rested and feeling better, I’ll have you bring him over for a visit.’ He looked towards the carriage but could see only the right elbow of the other guard and the head of its driver.

The carriage moved out past flamboyants budding red, rows of variegated immortelles, hibiscus courted by yellow butterflies, and sisal lances exclaiming like Jaja’s thoughts. It passed through the gate and made the right turn up Two Mile Hill. The carriage, an English Victoria, was stylish, fashionable, all black except for the olive-coloured upholstery, with full suspension springs. The body had been elegantly finished by Thorn of Norwich. Its collapsible hood, when fully extended, covered the entire seating area and two brass lamps hung on each side of the driver’s seat like closed eyes. It had been hired from George Whitfield, owner of the Central Ice House on Roebuck Street.

Jaja recalled his sojourn in St. Vincent: the crowds of people who looked like him on the quayside and their thunderous cheers as his carriage was rapidly driven away; the humiliating condescension of the administrator, Robert Llewelyn; the depressing conditions of the Captain’s Quarters on the windy promontory at Fort Charlotte; the rented house on Egmont Street next to the public offices; the policemen always on guard, keeping the curious labouring classes at bay; another policeman accompanying him wherever he ventured from home; the place he’d been moved to on Upper Bay Street near the wharf, with its foul reek of molasses; then, a year or so later, the move to Middle Street and more stringent curfews – no leaving his residence for more than four hours at a time, sleeping only at his own residence, needing approval to go beyond Kingstown, and having to state precisely where he was going.

These measures had come after the authorities received word from a ship’s captain that Jaja had offered to pay him well to take him to the United States.

The public events that Llewelyn arranged for him during his first year in St. Vincent were still sour in his mouth. He’d played along for a while, biding his time, knowing that they displayed him in public only to play down the true nature of his confinement. He’d played the laughing black man as he recounted stories of the Ashanti War in which he’d aided the British and the wars with his old archenemy, Oko Jumbo. The island’s small white elite were amused by his “charmingly picturesque” Creole speech. He’d worn that mask while looking for any opportunity to interact with local Blacks, thinking that one of his own race might help him to escape. One neighbour on Egmont Street became a good friend after he apprehended a man who’d stolen one of Jaja’s gold chains and tried to sell it to another neighbour. It was this man, Seymour, who’d told Jaja about a vessel that made a regular stop at St. Vincent on round trips from the U.S.A.

After the discovery, the invitations to cricket matches, concerts by the police band, visits to Government offices, shopping in the leading city stores and private dinner parties at Government House all ceased. The British had thrown their own masks to the floor: Jaja was no guest but a political prisoner who posed a threat to sovereign England. But even if the invitations had been renewed, he’d have pulled back like a sea anemone from the temptation of their bribes. Towards the authorities he cast only sullen looks. He embraced hatred and this venom kept him alive; for over a year it kept him keen and quick.

His home became alive with people who looked like him, who understood his condition and respected his kingship. Their company lifted his spirits. For the first two years of his exile, the local black people had been unaware of the real nature of his presence on the island. The newspapers, owned by members of the merchant class, supported the lie of the king’s voluntary presence. The truth was that on orders from the Secretary of State, Johnson, the vice-consul in Nigeria, had trapped Jaja on a British vessel under pretext of holding a meeting to settle a palm-oil trade dispute. Once aboard the vessel, Jaja had been brought to trial in Accra, a town that had no jurisdiction over him as a sovereign king, where he was convicted of breaking a treaty that outlawed other European nations from trading in the Delta hinterlands. The sentence? A hefty fine and five years exile. Britain had rejected his appeals and refused his request to present his case directly to the British Parliament.

*

Now, in the carriage, as he absorbed the green shade flanking the roadsides, Jaja felt a small quickening inside him, like that which chewing a kola nut brought. He inhaled the slow breezes and became aware of how much less he was coughing. Perhaps this hint of alacrity, this apparent improvement in his health, was merely the result of coming to a new place. Whatever the cause, it didn’t matter.

As the carriage crawled up Two Mile Hill, one of the guards asked him if, in a few days, he would feel able to accept an invitation from the Governor. Jaja said he would. The guard told him that George Washington’s half-brother, Lawrence, had been sent to Barbados nearly a century-and-a-half earlier as a treatment for consumption and that the climate had healing properties, particularly beneficial for diseases of the chest. Jaja suspected the guard was exaggerating, but he had to admit that the air seemed good and that he was already feeling some relief.

The property at Two Mile Hill more than met his needs. In fact, Walmer Cottage far exceeded them. He didn’t need a house with so many bedrooms, public rooms, and servants’ rooms. Yes, he was a king, but his current circumstances and his nature led him to value frugality. He had not become a king through lavishness, but through his sharp wits and restraint. Taking only well-judged risks, he had risen from being a slave to becoming an eminent tradesman with the Anna Pepple household at Bonny. Slavery’s only denial was kingship in the city-state where he had once been a slave. This was why he left Bonny and set up his own kingdom in Opobo, near the banks of the Imo River.

He felt sure Walmer Cottage had been chosen by the British just to extort six pounds five shillings in monthly rent from him, nearly double what he’d paid in St. Vincent. His allowance of eight hundred pounds, permitted by the British and provided by his chiefs in Opobo, would be sent directly to the Barbados Governor who would withhold his rent and miscellaneous expenses that included the care of the his pet dog, Oko Jumbo, maintenance of his carriage, two horses, and a cow. As he got out of the carriage and walked across the pebbled yard, Jaja took in the sheds that lined the back of the two-acre lot. The coach house stood at the far left so that one drove directly out of it along the curving driveway to the Two Mile Hill Road.

He would have needed accommodation like this if any of his wives, sons and servants had been with him, but he was alone. Four months earlier, in St. Vincent, his youngest wife, Patience, had refused to accompany him to Barbados, threatening suicide if she was forced to go. His son, Sunday, had left for study in England. In St. Vincent, servants and relatives had occasionally come from Africa to visit him. Now, as he recalled the modesty of his residence there, his mistrust of the authorities’ motives in lodging him at Walmer Cottage heightened. This mistrust increased further when, next morning, the officer who had accompanied him told him to expect another payment to be withheld from his allowance. First Secretary, who would deal with his affairs on behalf of the Governor, would inform him about this.

CHAPTER TWO

Becka heard a knock on the door of their two-room chattel house, and she looked up from the pot she was stirring. Her sister, Frances, was sweeping a corner of the room’s dirt-floor. Through the doorway to the bedroom, she could see her ailing mother lying flat on her back. She and Frances had been looking after her since their father died three years ago and their older brother, Fred, had left for Panama to fend for himself. Their chattel stood two miles south of the plantation from which their surname, Jordan, had come. Becka’s father had been born there a year before slavery ended. Her grandfather had died on the plantation and had taught his son coopering, the trade he’d lived from all his working life. Mr. Jordan had managed to save enough money to move into the tenantry, though he’d remained bound to the plantation for work and the estate still owned the land on which their chattel stood. Becka had been born in 1872 when her father was thirty-nine years old, and as the youngest she’d been his favourite.

‘Mornin’.’ A young woman in a maid’s uniform and bonnet stood on the makeshift coral-stone steps.

‘Patsy, how you? How de baby – my little man?’ Patsy lived in the same tenantry and had also worked at Jordan’s.

‘I awright, Becka. An de baby awright too. Eight months and growing good. How you mudda?’

‘Nuh worse. But tings rough, yuh know. Not much wo’k dese days.’

Patsy took a white cloth from between her breasts and opened it to show two phials. She held up the larger of the two and said, ‘Gi’ dis to she two times a day after she eat. It gwine clean she blood good-good.’

Becka took the gift and said, ‘You come all de way down hey to gimme this? I woulda see you at church Sunday… An wuh in de other phial?’

Patsy said nothing and looked away into the distance, her eyes following two blackbirds darting like daggers across the sky.

‘Patsy, wha’ wrong? Wha’ wrong?’ Becka asked.

‘I gwine just miss you bad.’

‘Wuh you mean? Girl, stop talkin’ in riddles, nuh.’

‘Mr. Brathwaite send me fuh you.’

‘Wuh you mean?’

‘He say he want you to wo’k fuh he. He waiting.’

Bidding her mother and sister goodbye, Becka took her purse off the hook near the door and she and Patsy stepped outside to enter the carriage parked a few yards down the track in the shade of the mahogany tree. She journeyed in silent apprehension through seas of sugar cane along the khus-khus bordered dirt road that led to Jordan’s Plantation.

After her father died from a sudden stroke, life had become even harder for them. Fred had been working on the canal in Panama for two years now; from time to time he sent them money. It was appreciated, but never enough, with Mrs. Jordan needing so much care. As the horses trod on in even rhythm, Becka began to wonder what was in store for her. She knew of young women who’d been summoned by their former masters and returned home spoilt, sometimes carrying the white man’s child. She’d wondered if Patsy was one of those women, but could never bring herself to ask. If Patsy ever told her any such thing, she, Becka, would be there to offer comfort. Letting her mind wander, her hand involuntarily clutched the purse.

She had asked, ‘Wuh in the other phial you gi’ me?’

Patsy leaned over and whispered, ‘Pure oleander juice. It ain’ mix wid nuthing,’

The quiet of Sundays always struck Becka. The villagers were mostly at home. Washed clothes were spread out to dry on coral stones at the sides of the houses. Pots were on fires. The men, after sleeping late, would be fixing things around the house: a broken chair leg, a broken chicken coop door. Children were running about in the yards making sport, playing fowlcock with the beaked quarters of mahogany pods or pitching marbles. It was not a quietness created by inactivity, but by the attitude that Sunday called for: some control, some respect for the Lord’s day, so one could speak freely, but not too loudly, could hammer a nail for oneself, but not too noisily.

Taking in the scene, Becka drank in the morning sun, felt the March breezes roll over her face, and responded with a long, wide-armed stretch. The driver slowed the carriage to a halt and Becka watched Patsy wedge her bundle under her arm, raise her cotton skirt and step onto the track hardened over the years by thousands of walking and running feet. She saw her friend walk over to the driver, and signal him to wait. Becka stepped out of the carriage, and the two of them walked out of earshot of the driver to talk.

Becka listened as Patsy urged her not to hesitate to use the oleander if ever she feared being taken advantage of. Talk was that the new owner of Jordan’s, Cheeseman Moe Brathwaite, always got the maid (whom Becka might be replacing) to bring him a cup of tea after he’d had his way with one of the female workers.

‘Dah would be de time to sneak it in,’ Patsy said. ‘If it doan kill he, it goin’ mess-up he brain or mek he balls dry-up.’

Becka reflected that maybe Patsy was as safe as any young woman could hope to be, working on an estate.

As soon as Becka was back in the carriage, the driver tipped back his old felt hat, flicked the reins, and the two horses started moving again. She looked back to see Patsy by her doorway waving a hand.

Fields of partially-harvested canes surrounded the last mile of their journey. As the carriage neared its destination, Becka could not stop thinking about the risks ahead. But she needed work if her family was to survive. She was not naïve. Women friends in the tenantry had told her things. As a house servant, you had to live there, not in your own chattel two or three miles away. You had to be ready to respond instantly to the needs of the family you served. You might have to pick some aloes from the yard to apply to one of the children’s bruises, or make a late-night beverage for the master or lady of the house, or, deeper in the night, when most everyone slept and the only sounds were the whistling frogs and crickets, you might have to hoist your nightdress when your door opened and the master’s heavy-set body filled the doorway, a smile on his beet-red face.

As Jordan’s came into view, Becka breathed deeply, her fears flitting like bats in her head. Should she ask the driver to take her back? He probably wouldn’t or couldn’t. She could hop off the carriage and run back home. She was strong and quick with good sturdy legs. But her sick mother waited there. Her sister, too, was also unemployed. She made a dress or skirt for somebody here and there, sometimes going to a jig with one of the villagers and allowing him to touch and know her in an unspoken negotiation through which she’d secure a few pence or some ground provisions.

The carriage pulled into the plantation yard. Blackbirds squawked in the high branches of the mahogany trees. This job would give her the security she and her family needed. She squeezed the purse she was carrying, feeling where the phial nested.

CHAPTER THREE

Jaja rose on the fingers of dawn. He still moved slowly and still coughed, but he felt brighter since his arrival. With a wide, slow-motion gesture (as if he were summoning his people to hear some important proclamation), he hoisted one of the eastern sash windows and unlatched and pushed open the green wooden louvres behind it. He held out his arms, closed his eyes and inhaled the morning air. The air here, though warmer, was less humid than in St. Vincent. It carried no chills and came in a constant flow, like wine with a pleasant aftertaste, or like the peaceful silence following a sparrow’s trill. In St. Vincent, the rough sea breezes that swept through his room in Kingstown, coupled with the depressions of forced exile, had been too much for him. Colonial Surgeon Newsam, after thoroughly examining Jaja, had told him, ‘The late high winds and heavy rains mixed with this infernally hot weather haven’t helped your health, Jaja. I can see that you’ve lost appetite and have not been sleeping well. If anything can be done for you, even now, it could be too late.’

‘I wish to spend my remaining days in Opobo, to die among my people,’ Jaja replied, looking towards Administrator Llewelyn who had entered the room.

‘I will make my recommendations,’ he said, ‘but you will have to give us your written pledge that if you were repatriated, you would refrain from any political activity in the Delta region. That’s my one condition. Would you agree to that?’

Jaja nodded.

Outside the room, Newsam said, ‘I know that the king has had a coffin ordered. He’s deeply depressed and grieving over his exile. He’s been coughing incessantly and complaining of chest pains. He has pneumonia and bronchitis – the last, I’m afraid, being of the chronic kind.’

‘He’s not a young man. How old is he? Sixty? Seventy?’ Llewelyn said. ‘It would not look good if he died on us.’

‘It’s imperative then that he be moved to a drier, more salubrious climate. I’d recommend Barbados. What do you think?’

‘He would be better off there,’ Llewelyn agreed. ‘When he’s recovered enough for travel, we’ll arrange to have him transferred. We must hasten to get all the paperwork in place.’

Before leaving St. Vincent, Jaja had been so depressed he wrote his will, naming Patience as executrix.

Now, through the second-storey bedroom window, Jaja saw the distant St. George valley undulating in an expanse of soft deep greens, its borders sharpened by the sunlight. From there, his eyes arced to the east and the west. Hillsides dotted with white houses. Coconut palms and trees waving in welcome and farewell.

Jaja thought he heard a knock on the house door. It came again. It couldn’t be one of the guards whose raps were always loud and irritating. Jaja put on his robe and looked down from the window.

‘Mornin’,’ a young woman called up. She wore a white bonnet and a white, long-sleeved cotton dress that reached to mid-calf. ‘I name Becka. Mister Brathwaite send me. I is you servant and nurse.’

‘Good morning. The constable will let you in, me girl,’ Jaja said.

The constable soon appeared and let the young woman in.

A little later, Becka knocked and came in with fresh bed-linen, and briskly began to change the sheets and pillow cases. She looked about eighteen years of age, close to that of his youngest wife, Patience, whom he still missed exceedingly. Like Patience, this girl was well-built and full-breasted. She had, he sensed, an agreeable disposition. His heart bucked in gladness as he watched her confident coltish steps whisk across the room with the bundle of old linen, keenly aware of Jaja’s eyes on her.

She paused by the door and said, ‘Mister Jaja, leh me know if you need anything. Mr. Brathwaite say you on special food and he gimme a list o’ things to cook fo’ you. You gwine be alright. I going now and fix you breakfast.’

‘All right, me girl,’ Jaja said. ‘I coming down shortly to you.’

When Jaja took his bath he noted that his skin wasn’t as clammy and as sweaty as before. Then he put on cotton pants, a colourful shirt, and sandals. He felt a little tingling in his throat and coughed into a handkerchief. He was relieved to find that, this time, there was no greenish-yellow sputum, no blood. He did, though, still feel weary and his joints and muscles ached. As he made his way unsteadily down the staircase, he began to doubt whether he would make it by himself. On the day he’d arrived, the two guards had helped him up to his room. He was about to call for one of them when Becka appeared near the foot of the staircase, carrying breakfast on a tray. She saw him grasping the railing.

‘You awright, Mr. Jaja? You awright?’ She placed the tray on a side table and hurried up to him. She placed her right arm under his shoulder and slowly guided him down the remaining steps.

‘Yes… yes… yes. Thank you, me girl,’ Jaja said. Becka steered him to the dining room and sat him down. Then she retrieved the breakfast tray and placed the food before him: a glass of lemon juice, a bowl of oatmeal, and fresh, warm cow’s milk.

‘I goin’ come back when you done,’ she said.

Jaja nodded and said, ‘Call de guard here.’

The constable arrived shortly afterwards, and Jaja told him that, for now, he’d prefer to sleep in a guest room on the ground floor so as not to aggravate his sore muscles and joints by going up and down the staircase.

‘You can leave my upstairs bedroom as it be,’ Jaja said, ‘for I expect sleep back in it before too long.’

‘I’ll have it arranged,’ the constable said and returned to his second-floor station at the back of the house.

When Becka returned, Jaja informed her of the arrangement and asked her to bring his clothes and medicines down to where he’d be sleeping. Jaja saw Becka look at his empty plate. She’d clearly been informed of his condition – the inflammation of his lungs and the resulting loss of appetite. He, too, looked at the empty plate. Perhaps he might get better and his regular weight return. They looked at each other and smiled.

CHAPTER FOUR

Becka opened the pantry door to see what she could prepare for the king’s lunch and dinner. The shelves brimmed with ground provisions grown at Jordans – sweet potatoes, yams, eddoes and pumpkins. Worrell, Walmer Cottage’s gardener and handyman, would bring her lettuce from the garden he tended a couple of hundred feet from the north end of the house, but hidden from it by guava, sapodilla, mango, sour-sop trees, and coconut palms. Here, he grew okra, cabbage, spinach, beets, and herbs such as thyme, marjoram, sage, basil, mint and chives.

‘Becka! Becka! Look hey!’ It was Worrell calling from the yard. She hated being disturbed when she was in the middle of her chores – she was cooking the king a vegetable soup for lunch – but went out to the yard to see what Worrell wanted. He was standing next to a large container about six feet tall. She heard the sound of horses’s hooves and saw the back of a large cart moving like a beetle along the path that led to Two Mile Hill Road.

‘Dese goods just get hey from Trafalgar House. I gwine tek dem out-o-de big box hey and you can tek dem in,’ Worrell said. Becka sighed, exerting her authority as the controller of all things pertaining to the house. Only she and the king really lived here. The guards, the one stationed outside the side door and the other at the top of the back outer staircase, worked in rotation with other guards. Worrell lived in a nearby tenantry. She knew Worrell liked her, but she had no romantic inclinations towards him whatsoever. She was just happy that she wasn’t working at the plantation. No sooner had Mr. Brathwaite, thumbs in his watch-dangling waistcoat, offered her the job at the cottage just outside Bridgetown, than Patsy’s words sprang to her head: I gwine miss you bad. Patsy had obviously known where Mr. Brathwaite intended to send her, though she had also thought it wise to prepare Becka for the worst with her wisdom laced with oleander juice. Perhaps Brathwaite had given Patsy this information in the hope that it would make her feel comfortable with his offer. And though she wasn’t so naïve as to think that Walmer Cottage provided complete immunity from Mr. Brathwaite – if he got any ideas – the fact that he rarely stayed at this residence, and its distance from Jordans, made her feel more at ease.

Worrell said, ‘I ask de driver if dese things fo’ de king and he say, “De king? Who king dah? Wha’ king you talking ’bout?” He did real surprise. I ask he if he didn’ hear ’bout de African king that Queen Victoria send down hey as a pris’na?’

Becka said, ‘Even up in de country people hear ’bout um. Some country vendors was down there when he come in at de Wharf. One o’ dem tell my sister.’

Adjusting his brown felt hat, Worrell said, ‘Well, de driver sey he hear ’bout he, but didn’ know de goods he bring up was for he. Dah is wha’ surprise he. Before he pull out – jus’ befo’ you come down – he stare at me and sey, “Wha’ king wha’? He could be a king? Wha’ sorta king could let dem English people capture he and send he down hey so?”’

Becka felt a defensive wind billow inside her.

‘Dat driver is a idiot, a stupid idiot. Doan pay him nuh mind.’ Her intensity brought Worrell back to his task. He fumbled a pocket knife from his worn gaberdines and began to break the seals on the carton. Becka saw the words TRAFALGAR HOUSE stamped in bold block capitals and, in smaller capitals, RECEIVED FROM LONDON, LIVERPOOL, AND NEW YORK. Worrell removed cases of Swiss-manufactured condensed milk, Neave’s oatmeal, Robinson’s patent barley, and Fry’s cocoa and chocolate sticks. As he carried the items to the door, Worrell, muscular and short, moved back and forth like a rubber ball, allowing Becka to imagine she heard tuk-band music accompanying him. Bags of sago and tapioca, pears and apples, bags of rice, currants, citron peel and pudding raisins, white and pink sugared almonds, conversation and peppermint lozenges, lemon drops, white and pink corianders, nonpareil comfits, acidulated pear drops, twisted barley sugar, clanging balls, and a bottle or two of whiskey made their way into the house. Some of these items would not be good for the king, and Becka was determined to protect him. Only occasional sweets for him. And certainly none of the scotch, some of which she’d already discovered in a cabinet. Her duty was to nurse him back to full health.