U.P. Reader -- Issue #1 E-Book

3,43 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Michigan's Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure chest of writers and poets, all seeking to capture the diverse experiences of Yooper Life. Now U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.'s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The twenty-eight works in this first annual volume take readers on a U.P. road trip from the Mackinac Bridge to Menominee. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about.

Whether you're a native Yooper or just wish you were, you'll love U.P. Reader and want to share it with all your Yooper family and friends.

"U.P. Reader offers a wonderful mix of storytelling, poetry, and Yooper culture. Here's to many future volumes!"

--Sonny Longtine, author of Murder in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

"Share in the bounty of Michigan's Upper Peninsula with those who love it most. The U.P. Reader has something for everyone. Congratulations to my writer and poet peers for a job well done."

--Gretchen Preston, Vice President, Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association

"As readers embark upon this storied landscape, they learn that the people of Michigan's Upper Peninsula offer a unique voice, a tribute to a timeless place too long silent."

--Sue Harrison, international bestselling author of Mother Earth Father Sky

"I was amazed by the variety of voices in this volume. U.P. Reader offers a little of everything, from short stories to nature poetry, fantasy to reality, Yooper lore to humor. I look forward to the next issue."

--Jackie Stark, editor, Marquette Monthly

"Like the best of U.P. blizzards, U.P. Reader covers all of Upper Michigan in the variety of its offerings. A fine mix of nature, engaging characters, the supernatural, poetry, and much more."

--Karl Bohnak, TV 6 meteorologist and author of So Cold a Sky: Upper Michigan Weather Stories

U.P. Reader is sponsored by the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA) a non-profit 501(c)3 corporation. A portion of proceeds from each copy sold will be donated to the UPPAA for its educational programming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 146

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

2017 | Issue #1

U.P. READER

Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World

A publication of the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA)Marquette, Michigan

Castle Rock, St. Ignace - 1920

U.P. Reader: Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World -- Issue #1

Copyright © 2017 by Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA). All Rights Reserved.

Learn more about the UPPAA at www.UPPAA.org

Visit UP Reader online at www.UPReader.org

ISSN: 2572-0961

ISBN 978-1-61599-336-9 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-337-6 eBook

Managing Editor - Mikel B. Classen

Associate Editor and Copy Editor - Deborah K. Frontiera

Logistical Support & Website Creation - Victor R. Volkman

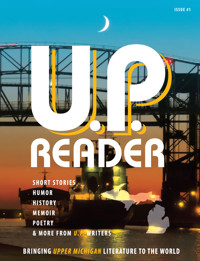

Cover Photo “Freighter and Moon” - Mikel B. Classen

Cover Design – Doug West

Interior Layout – Michal Šplho, Design Amorandi

Distributed by Ingram (USA/CAN/AU), Bertram’s Books (UK/EU)

Published by

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

CONTENTS

Introduction

by Mikel B. Classen

The Song of Minnehaha

by Larry Buege

Fragile Blossoms

by Deborah K. Frontiera

Winning Ticket

by James M. Jackson

Stocking Up

by Janeen Pergrin Rastall

We Are Three Widows

by Sharon M. Kennedy

U.P. Road Trips

by Jan Kellis

The Story-Seer

by Amy Klco

Lonely Road

by Becky Ross Michael

An Abandoned Dream

by Elizabeth Fust

Jacqui, Marilyn, & Shelly

by Terry Sanders

Marquette Medium

by Tyler Tichelaar

U.P. Reader is accepting submissions for Issue #2

The House on Blakely Hill

by Mikel B. Classen

Iced by Lee Arten

Hoffentot Magic

by Roslyn Elena McGrath

Ann Dallman:

Wolf Woman

Menominee County/My Hometown Abandoned

Christine Saari:

At Camp

Nonetheless

Katydids

by Aimée Bissonette

Source by Frank Farwell

A Tribute to Dad

by Sharon M. Kennedy

Ar Schneller:

Nightcrawlers

Her Skin

Champ

Heartwood

by Rebecca Tavernini

Edzordzi Agbozo:

Rewinding

Final Welcome

The Visitors

by Sarah Maurer

Active Dreams

by Sharon Marie Brunner

Introduction

by Mikel B. Classen

When we came up with the idea for the U.P. Reader, we wanted to create a forum for authors from the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association where we could showcase the talent within the organization and promote their writing. We put out a call for material and we received some of the best. This volume is the result of some of the incredible writing talent we have within the UPPAA.

Filled with stories and poetry, this first volume took on a life of its own. The submissions that came in started to show the real potential of what this project could be. We were pleasantly surprised at the high quality of writing that appeared with every submission. We knew we had some excellent potential out there, but to see it come in first hand was a real treat.

What you hold in your hand is the result of this writing “experiment.” The U.P Reader, Issue #1, has exceeded all of our expectations. And we hope it will exceed yours. Enjoy some of the finest Yooper writing ever placed between pages in the premier issue of U.P. Reader.

I really need to thank Deborah Frontiera for editing, helping with submissions and making sure that info about the project got out to the membership as well as moral support. I also need to thank Victor Volkman for helping with graphics and getting the U.P. Reader into print. This would not have been done without him. I need to thank Tyler Tichelaar and the UPPAA board for believing in the project and making it a reality. And most of all I want to thank the contributors without whom none of this would be possible.

Enjoy!

Mikel B. Classen –Managing Editor

Loading copper ingots, Houghton

The Song of Minnehaha

by Larry Buege

Sean, I went to town for groceries. I’ll be back by noon. There’s a breakfast burrito in the freezer. Nuke it for two minutes. And don’t forget your insulin, ten units of regular and twenty of Lente.”

Never marry a nurse; they always treat you like a patient. I’ve been taking insulin for twenty years. One would think that would suggest a modicum of medical knowledge. Despite her occasional nagging, Clara has been a good wife. I write, “I’ll be in the woods when you return,” at the bottom of Clara’s note and leave it on the kitchen table. My penmanship has never been great; now, with the arthritis in my hands, it is barely legible.

I walk over to the fridge and remove the vial of regular insulin; I won’t need the Lente today. The breakfast burrito also does not fit my plans. I place the insulin in a plastic grocery bag and head for the den.

We’ve been spending summers in this cabin overlooking Lake Superior for thirty years. It is no longer a second home; for me, it is home. This is where I found motivation to write. Some of my best works owe their conception to a small spark of inspiration gleaned from these forty acres of Upper Peninsula wilderness.

Most of the cabin belongs to Clara, but the den is mine. It is small, to be sure, but it provides my basic needs. The fabric on my red sofa is worn and frayed. If Clara had her way, it would have been banished to sofa heaven years ago. (It has too many memories for me to discard.) Up against the window overlooking Lake Superior is my oak desk. This is where I did my writing, first on a manual typewriter and then by computer. I say that in past tense since my arthritis prevents all but the most essential writing. Now, only my dictionary and thesaurus remain on the desk. They were my workhorses, receiving extensive use as I searched for that elusive stronger verb or that more descriptive noun. Samuel Clemens purportedly said, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.” Sam was a wise man.

The walls are covered with knotty pine, although bookshelves and pictures obscure much of it. Most of the pictures I took myself: local landscapes and spring flowers. One picture is of a much younger me accepting a Pulitzer Prize for my fifth novel. I find that a bit vain, but Clara insists it remains on the wall.

The bookshelves are where I store my memories and contain the more important books I have read over the years. Even now, as I look at the titles and then close my eyes, I can replay the stories in vivid detail. My memory is one of the few physical attributes that has not exsanguinated with age. My other senses have been relegated to the endangered species list. Despite three laser surgeries, doctors predict diabetes will claim my eyesight within a year.

Twenty-three books on the shelf have my name on the spine. I hope that is a worthy legacy of my life. It is a silly thing for an old man to think about. I pull an old, leatherbound book from the top shelf and add it to the insulin in my plastic bag. Of all the books on the shelf, this is the book I hold in highest esteem—even above those I have authored. I close the door to the den behind me and exit the cabin through the back door.

It will be a warm day. The matutinal sun is already above the trees, suffusing the clearing in which the cabin stands with sunlight. The radiant warmth feels good on my skin. I head down a well-worn path into the woods, a trip I make daily in the summer. The path is lined on both sides by trilliums, a sure sign of spring. It is one of nature’s eternal truths; trilliums will be blooming in spring thousands of years after maggots have finished dining on my remains. About one hundred yards into the woods, the path opens into a clearing of sorts. The trees still provide a canopy overhead, but the ground has been cleared of underbrush, revealing a small brook. It is too small to qualify as a stream or even a creek. It is only two feet across at its widest spot and in the dry summer months is almost non-existent. The brook drains down from the hill above the cabin and culminates in a gentle waterfall of no more than three feet in height. The water gurgles as it cascades from one rock to the next.

I sit down on a reclining lawn chair I keep there for that purpose; even the short walk from the cabin leaves me tired. I write in my den, but this is where I think. The formula for a good novel, I have discovered, is two parts thinking and one part writing. I take the insulin from the bag and draw up 100 units; I assume that will be sufficient. Then I inject it into the subcutaneous tissue of my belly. I do not bother with the perfunctory alcohol swab.

I take the book out of the bag and caress the aged leather binding. Books have been my life, my sole reason for existence. That had not always been the case. I close my eyes and remember that summer day in 1954. The war in Korea had ended and times were good. I remember standing before that square edifice of red brick and stone that squatted on a small knoll overlooking Union Street. Its windows were tall and slender and arched at the top like a cathedral. Their lower ledges were well over six feet tall, precluding any thought of peering in—not that I cared to—and the door to the building was recessed in a cave-like structure covered by a high, vaulted arch of cut stone. A drawbridge would not have been out of place. Above the arch, etched in sandstone, was Carnegie Public Library, Sparta, Michigan.

I had walked past the building on my way to school, but I had never been inside. I had walked past many buildings on my way to school, none as formidable as that stone fortress now peering down on me. No other building so totally dominated the landscape or so filled me with trepidation.

School was out for the summer, and fifth grade wouldn’t begin until fall; I could find no logical reason for my being there. Summers were for fun and excitement. I should be standing on the pitcher’s mound, throwing fastballs in Little League and bowing to cheering crowds. Someday I would stand on the pitcher’s mound at Tiger Stadium. When I closed my eyes, I could hear the roar of the crowd as my fastball whipped over the plate for strike three. This was not to be; a cast on my right wrist prohibited any fastballs. I was out for the season.

With the summer in ruins and nothing significant to occupy my time, I had been relegated to errand boy, returning a library book for my mother. It was a degrading chore at best: books were for girls; baseball was for boys. My mother asked that I personally give the book to Mrs. Weaver, one of the librarians and a close friend of my mother’s. According to my mother, Mrs. Weaver was a full-blooded Ojibway. Weaver didn’t sound very Indian to me.

Once I was assured none of my friends was watching, I slipped into the library. The inside was smaller than I had imagined. It was one large room with rows of bookshelves lined up like fields of corn. They were so tall I would have been unable to reach the top shelf, if for some unforeseen circumstance the need should arise. In the center, sitting at a large oak desk, guarding the books, was an elderly lady with hair that was not gray, but white like freshly fallen snow, and it billowed up in a bun like a snowdrift. Her skin was unusually tanned for this early in the summer. Hanging around her neck by a chain was a pair of turtle-shell glasses, a fitting accouterment to her profession. The name plaque on her desk identified her as Minne Weaver.

“Mrs. Weaver?” I said as I cautiously approached the desk as one would a trial judge.

She looked up and scrutinized all four-foot-two of me, paying particular attention to the flaming red hair protruding from under my Detroit Tigers baseball cap. “You must be Sean Connolly. I talked to your mother yesterday.”

We had not previously met, but with my red hair, I was not difficult to pick out of a crowd. As the summer progressed, my face would be covered with freckles. The red hair I could tolerate; the freckles I could do without.

“Are you really an Indian?” I asked. “You don’t look like an Indian.” My mother would have been horrified by my question, but it was something any ten-year-old would need to know.

“You don’t look much like Daniel Boone either,” she replied. “You’re thinking of historical Indians like you see in the movies.” She opened her purse and pulled out a well-worn picture. “This is my grandfather.”

I looked at the man in the black and white photo. He had dark skin and high cheekbones, and his hair was black with braids on both sides. Although he was wearing an old-style, tailored suit, he was very much an Indian. I could visualize him riding scout for John Wayne.

“There are many Indians in the Upper Peninsula where I grew up,” she said. “My husband and I married after college. John worked for the mines as a geologist. When he died four years ago, I moved down here to work in the library.”

Her eyes began to water—old people tend to get sentimental at times. I felt bad; I had only wanted to know if she was Indian. She grabbed a tissue from her desk and dabbed her eyes dry as if no explanation were needed.

“My mother asked me to return this book.” I laid the book on her desk, hoping the distraction would alleviate her sorrow.

She checked the due date and set the book on a rolling cart half filled with books. Then she gave my red hair and cap another onceover. “You must be a Tigers fan.”

“Yes, ma’am. I’m going to play for the Detroit Tigers when I grow up. My uncle promised to take me to one of their games when he comes home from Korea.” I looked down self-consciously at the cast on my wrist. “I fell off my friend’s horse a couple of weeks ago and broke my wrist. I’d be playing ball now if it weren’t for this.” I held up my cast as exhibit “A”.

“That can happen to any ballplayer. Even Casey had his bad days.”

“Casey? Who’d he play for?” I had baseball cards for Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Mickey Mantle, and all the baseball greats, but I couldn’t remember anyone named Casey. He had to be a minor leaguer.

“You never heard of Mighty Casey of the Mudville Nine?”

I felt a bit of shame. “No, ma’am.”

“We need to correct that. I’ll be right back.” The lady disappeared into the cornfields and reappeared with a well-worn book. “Take this home and read ‘Casey at the Bat’ on page 29.” She handed me the book. The title of the book was The Best of American Poetry. I felt trapped. The noose was tightening around my neck and the trap door quivered beneath my feet. I couldn’t just give the book back to her.

“Just make sure you return it in two weeks.”

I left the library with the book of poetry under my shirt. If any of my friends were to see it, I’d never survive the razzing… and poetry of all books. Ten years old and my manhood was already in question. I gave the baseball field a wide berth to avoid any encounters with close friends and arrived home with my pride intact. I yelled a quick “hello” to my mother, who was fixing dinner in the kitchen, and headed upstairs to my room. I didn’t feel safe until my bedroom door was securely closed behind me. I would hide the book under my mattress and smuggle it back into the library the following morning. No one would be the wiser.

Before Mighty Casey was sequestered in the safety of my mattress, I had to see who he was. I turned to page 29, finding “Casey at the Bat” by Ernest Lawrence Thayer.

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day.

The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play,

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

The legendary Harry Caray couldn’t have better described the game. I continued reading down the page, fascinated with the rhythm of the story. It was as if I were there or at least listening to the play-by-play description on the radio. I had no doubt Mighty Casey would save the day.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright,

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and little children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville? Mighty Casey has struck out.

The ending was a letdown; I had wanted Casey to clear the bases. This was unlike any poetry I had ever read. There was no flowery language or mushy romance. It was a poem a boy could read without shame, not that I planned to tell anyone. I scanned the table of contents but found no more baseball poems. “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” piqued my interest; I liked horses. I turned to page 89.

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

For the next few minutes I rode “through every Middlesex village and farm, for the country folk to be up and to arm.” I could feel the wind in my face as my trusty steed galloped through the countryside. The horse’s mane stung as it whipped across my cheek, but I didn’t care. I rode through Lexington and on to Concord, all the time yelling, “The British are coming! The British are coming!” Finding nothing more of interest in the book, I stashed it under my mattress.