U.P. Reader -- Issue #2 E-Book

5,98 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Michigan's Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure trove of storytellers, poets, and historians, all seeking to capture a sense of Yooper Life from settler's days to the far-flung future. Now U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.'s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises. The thirty-six works in this second annual volume take readers on U.P. road and boat trips from the Keweenaw to the Straits of Mackinac. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about. U.P. writers span genres from humor to history and from science fiction to poetry. This issue also includes imaginative fiction from the Dandelion Cottage Short Story Award winners, honoring the amazing young writers enrolled in the U.P.'s schools. Whether you're an ex-pat, a visitor, or a native-born Yooper, you'll love U.P. Reader and want to share it with all your Yooper family and friends.

"U.P. Reader offers a wonderful mix of storytelling, poetry, and Yooper culture. Here's to many future volumes!"

--Sonny Longtine, author of Murder in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

"Share in the bounty of Michigan's Upper Peninsula with those who love it most. The U.P. Reader has something for everyone. Congratulations to my writer and poet peers for a job well done."

--Gretchen Preston, Vice President, Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association

"As readers embark upon this storied landscape, they learn that the people of Michigan's Upper Peninsula offer a unique voice, a tribute to a timeless place too long silent."

--Sue Harrison, international bestselling author of Mother Earth Father Sky

"I was amazed by the variety of voices in this volume. U.P. Reader offers a little of everything, from short stories to nature poetry, fantasy to reality, Yooper lore to humor. I look forward to the next issue."

--Jackie Stark, editor, Marquette Monthly

"Like the best of U.P. blizzards, U.P. Reader covers all of Upper Michigan in the variety of its offerings. A fine mix of nature, engaging characters, the supernatural, poetry, and much more."

--Karl Bohnak, TV 6 meteorologist and author of So Cold a Sky: Upper Michigan Weather Stories

U.P. Reader is sponsored by the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA) a non-profit 501(c)3 corporation. A portion of proceeds from each copy sold will be donated to the UPPAA for its educational programming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 317

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

2018 | Issue #2

U.P. READER

Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World

A publication of the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA)Marquette, Michigan

www.UPReader.org

U.P. Redder

Issue #1 is still available!

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure chest of writers and poets, all seeking to capture the diverse experiences of Yooper Life. Now U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.’s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The twenty-eight works in this first annual volume take readers on a U.P. Road Trip from the Mackinac Bridge to Menominee. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and eBook editions!

ISBN 978-1-61599-336-9

U.P. Reader: Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World -- Issue #2

Copyright © 2018 by Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA). All Rights Reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Learn more about the UPPAA at www.UPPAA.org

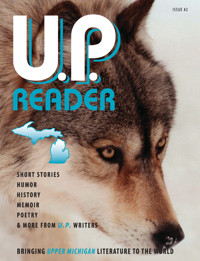

Cover Photo: "U.P. Wolf" by Mikel B. Classen. This was shot a few years back in northern Marquette County. That was back when I carried a Pentax and still shot with film. This was taken with a 200 mm telephoto lens on 35mm film. I've always felt that the wolf is the embodiment of the spirit of the Upper Peninsula. Loyal to its family, yet independent and tenacious, a creature that has overcome all odds to survive, the wolf's struggle reflects our struggles. There is no U.P. wilderness without the wolf. To hear the call of the wolf echoing across the untamed landscape is to truly live.

ISSN: 2572-0961

ISBN 978-1-61599-384-0 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-385-7 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-386-4 eBook

Managing Editor - Mikel B. Classen

Associate Editor and Copy Editor - Deborah K. Frontiera

Production Editor - Victor Volkman

Cover Photo - Mikel B. Classen

Cover graphics and Layout - Michal Šplho, Design Amorandi

Distributed by Ingram (USA/CAN/AU), Bertram’s Books (UK/EU)

Published by

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

CONTENTS

Introduction by Mikel B. Classen

Tales from the Busy Bee Café

by John Argeropoulos

A Geology Geek Finds God

by Leslie Askwith

Silent Night by Larry Buege, 4th Infantry Division 1967-68

Au Train Rising by Mikel B. Classen

Bear Woman by Ann Dallman

Superior Sailing

by Deborah K. Frontiera

The Typewriter by Elizabeth Fust

Minié Ball by Giles Elderkin

Please Pass the Wisdom by Jan Stafford Kellis

One Shot Alice by Sharon Kennedy

Saturday Mornings on Chestnut Street

by Sharon Kennedy

True Confessions of an Introverted, Highly-Sensitive Middle School Teacher

by Amy Klco

Death Comes to Visit by Amy Klco

On Turning Forty by Jennifer Lammi

“Yoopers” by Raymond Luczak

How Copper Came to the Keweenaw Peninsula by Raymond Luczak

Rants of a Luddite by Terri Martin

The Yooper Loop by Terri Martin

Roslyn Elena McGrath Winded

Roslyn Elena McGrath Stop Clocks

Slip of the Lip

by Becky Ross Michael

The Legend by Shawn Pfister

At Camp: When the Cat Is Out of the House by Christine Saari

Habitat by Christine Saari

Inception Through a Shared Fantasy

by T. Sanders

Gregory Saxby

On the Circuit

The Last Tear

Ar Schneller

Twinkle Twinkle Imaginary Star

Ar Schneller

Dying to Know

The Attack

by Katie McEachern

Welcome to the New Age

by Emma Locknane

T. Kilgore Splake

Brautigan Creek Magic

Another Morning

Bottom Feeder by Aric Sundquist

Jon Taylor

A Song Cover

A Sighting

The Blueberry Trail

by Tyler Tichelaar

Cedena’s Surprise

by Donna Winters

The Final Catch

by Jan (“Jon”) Wisniewski

Introduction

by Mikel B. Classen

Welcome to the second issue of the U.P. Reader. It is hard to believe that it has already been a year—and what a year it has been! When we started this adventure, like most, it was a journey into the unknown. And like most adventures, there’s always the danger that everything could fall flat and die. Things could get ugly. Fortunately, that was not how this turned out. Bookstores liked it. Those that picked it up seemed to like it. Feedback was from favorable to excited. The U.P. Reader exceeded our expectations. We began working toward a Volume Two, but the first issue wasn’t done surprising us.

The first issue of the U.P. Reader reached out and found its way to some surprising places. The state Library of Michigan requested that we submit the U.P. Reader to their Notable Books program. We did. We didn’t win, but we were invited. Then we heard that two of the selections, Larry Buege’s “Song of Minnehaha” and Frank Farwell’s “Source” were both nominated for Pushcart’s Best of the Small Press award. Results will be announced in late spring this year. So, that’s still out there. Consequently, we were thrilled with the adventure of Volume One. If you missed the original Volume One, ask for it wherever you found Volume Two (which you are holding right now).

Now, I sit with the second issue in hand. I’ve seen the work and I realize how much improved Volume Two is. We have many of our favorite authors from the first issue, plus many new ones who are talented and fun. We have also included, for the first time, a “Young U.P. Authors” section. This evolved from the newly inaugurated Dandelion Cottage Short Story Contest (www.DandelionCottage.org) involving the Upper Peninsula public schools and put on by the Upper Peninsula Publishers & Authors Association (www.UPPAA.org). The entries were judged and the top two winners’ stories appear in this issue. The U.P. Reader is proud to have these young writers aboard. It gives us a more rounded selection. I hope to continue this feature with every issue.

Volume Two has more writers and poets represented and more material, for which we doubled the size. It is my hope that, once again, the U.P. Reader will reach out and exceed not only our expectations, but also those set by Volume One. Onward to the next adventure!

If you have ever had the inclination to write poetry, prose, or stories, we invite you to join your neighbors in the UPPAA today.

Mikel B. Classen,Managing Editor andDeborah K. Frontiera,Editor

Victor R. Volkman,Production Editor

Tales from the Busy Bee Café

by John Argeropoulos

Yianni knew that the filming of the courtroom scenes for Anatomy of a Murder would continue for at least another hour or two, yet he was needed elsewhere. He had to reluctantly close his notebook and relinquish his coveted balcony seat in order to get back to the restaurant where his parents relied on him during the evening rush hour. The filming was a magnet for everyone in the area, including Yianni, but he knew that he would soon be involved with characters and stories every bit as interesting. He covered the five blocks to the Busy Bee Café quickly and was relieved to discover that he was not late for the main event.

Like clockwork, all the regulars began to assemble for what is best described as a form of gustatory street theater. Karl Manheim, a local DJ and a high-strung loner by nature, was the first to arrive. He sought out his usual stool at the far end of the counter near the door. It was a puzzling place to sit for a person who has just emerged from the confines of a hectic studio job since it was situated directly across from the small radio that was always blaring.

Karl had no sooner placed his favorite order for baked ham and picked up the local paper than he became visibly agitated and began shouting, “That damn Bolero!” Only a handful of people knew the inside joke that was being perpetrated by Bill Thompson, his colleague at WDMJ radio, who fiendishly selected all of Karl’s most hated music for this time slot, knowing full well that Karl was a captive audience at the diner.

With uncanny timing, Ray Russo raced in, tossed his lunch bucket on the floor, and plopped down a couple stools away from Karl. In his characteristically obtuse manner, a mixture of natural ebullience and childlike innocence, Ray blurted out, “Is that Madame Butterfly?”

“Madame Nhu, you idiot!” scowled Karl.

The intended bullet missed its mark as Ray kept smiling blissfully, wondering aloud about how much things had changed since his Army days in Japan. The thought of it consumed him and Ray constantly talked of going back someday to find out. He had been saving every spare coin for that glorious day for the past three years, but he realized that it was just a dream and that it might never happen on the abysmally low wages he earned at the Cliffs Dow Chemical plant. He faithfully trekked the six mile roundtrip from his rooming house on Baraga Avenue every day, choosing to use the money saved on bus fares for his trip. Perhaps it was this motivation that propelled him with the speed that would be the envy of an Olympic race walker. “Race-Walker Ray” with the big smile and trusty lunch box was always a head turner on his way to work and back.

Lost in all the commotion was the “Bean Man,” who had unobtrusively edged his way toward a view of the specials listed on the handwritten chalkboard that served as a menu. Barney’s dress and demeanor never changed from visit to visit. A mousy-looking man with thick glasses, a floppy cap, and a long tattered coat to match his forlorn appearance, Barney’s focus was riveted on the chalkboard. If he spotted his obsession for home-baked beans, a trace of a smile would briefly betray his great joy and he would quickly sit down. If the object of his delight was not included, he would turn, crestfallen at his misfortune, and slink out the door. On occasion he might muster the courage to ask about the beans, hoping against hope that they might have been somehow overlooked, but on this day he disappeared without a word.

Not at all amused by any of these proceedings, Oscar was holding court at the other end of the counter. A tall, brawny, bald man with a booming, resonant voice, he always wore a white flannel long-sleeve shirt and baggy black trousers with big red suspenders. Oscar bellowed about the fact that chemicals had ruined the taste of everything, including his favorite brand of beer, and that chemicals would soon be the death of us all.

Charlie, who was seated next to Oscar on the end stool next to the kitchen and who worked at the sawmill where Oscar was the night watchman, simply stared straight ahead and shook his head from time to time. He knew better than to challenge Oscar’s ranting, but he also lacked the ability to speak beyond very simple statements about the weather or some other equally innocuous topic. Charlie would usually be the last customer to leave each night, often having spent hours drinking coffee and feeding the jukebox in an effort to forestall another lonely night at his shack on the south side of town. We all knew that he had been kicked out of school in the middle of the third grade for defying the school principal, Miss Macy, and that he never tried to return. His lot in life had been a series of low-paying, grueling jobs with little or no future, but he nonetheless exhibited a gentle quality and never whined about life’s unfairness.

A group of workmen from a highway construction job began to file in from Joe’s Tavern down the street. They always sat together at the same table and were a boisterous, fun-loving group of guys who liked their beer, good food, and tall tales as a way to banish their aches and pains. Most of the regulars tended to ignore them unless they happened to overhear a particularly funny story. Although they were usually loud, the workmen were mostly pretty well behaved and there was little reason for the regulars to interact with them. However, tonight there was an altercation that erupted so quickly and with such violence that everyone was stunned. It seems that one of them had a bit too much to drink and became engaged in a heated argument with a fellow at the next table, calling him a “jarhead.” With lightning speed and a maniacal look in his eyes, the ex-Marine jumped to his feet, picked up a chair, and slammed it into the head of the offender. Blood was spurting all over the stricken man’s face and shirt, some of it dripping down to the table and onto the floor.

What happened next caught most people by surprise. Everyone was bracing for some type of retaliation, but once it was determined that the wound was not life threatening, the group quickly decided to pay their bills and get out before any police showed up. Apparently this was not the first encounter between the two combatants and their friends were worried about possible jail time, which they hoped to avoid by taking their buddy to the emergency room and claiming that he had been injured on the job.

Tony, a local roofer who frequented the same bar, turned from his stool and laughed at the bedlam, saying that the jerk had it coming, and in fact was overdue for shooting his mouth off all the time. Nobody took issue with his comments and Tony resumed his meal, although he continued to mutter to himself about guys who couldn’t hold their liquor.

The ensuing lull provided a respite in the kitchen where Sam, the owner-cook had been scurrying to keep up with the onslaught of orders. His wife, Angela, who labored as his faithful partner, took the opportunity to get some of the dishes washed and asked their son, Yianni, to keep an eye on the needs of the dining room. Being immigrants from Greece, the couple often unconsciously lapsed into their mother tongue, when they encountered a stressful situation like the fight.

Early Settler - Grand Island

Sam and Angela’s comments were overheard by Max Geiger, who was seated at the back table nearest to the kitchen. Max did not take kindly to such talk, and he hollered, “Hey, talk American back there!”

Tony wheeled around on his stool and glared at Max. “You shut your mouth if you don’t want some of what the last guy got.”

Max’s fiery temperament had served him well during his days as a hockey player who liked to mix it up and excite the crowds at the Palestra, but then a freakish accident suffered while working in a warehouse ruined everything. A pile of pallets collapsed and threw him against a row of large storage barrels, severely injuring his right hip and knee, permanently robbing him of his ability to continue his hockey career. Perhaps even worse, the incident also deprived him of a natural outlet to vent some of his aggressive personality and this left Max vulnerable at times like this when his temper got out of control.

Max started to get up, his hand wrapped tightly around his cane that could have served as a club, but he thought better of it. He realized that he would be no match for the bull-necked roofer, even though Tony was obviously showing the effects of his ritual round of boilermakers at Joe’s.

Yianni glanced at his watch while refilling Charlie’s bottomless cup, noting that it was already past 7 p.m. On most nights the dinner trade would be winding down about now, but this was Friday night. Friday night was the big night of the week because the downtown merchants stayed open until nine o’clock. Hordes of town folks would come streaming in from all directions, creating a shopping and entertainment frenzy.

Among the customers who only appeared on Friday nights was Pete Splake, who predictably ordered his usual hot pork sandwich with extra gravy. Sam had spotted him come in and had already started to prepare the order. Yianni could rarely get a word out of him, but he was fascinated by the stories that he had heard over the years. Splake had a reputation for being able to live off the land as a trapper, hunter, and fisherman of almost mythical proportions. Not only did he know where the best fishing was, but he could catch trophy-size fish by stealthily placing his hand in the water and actually stroking the belly of the fish before deftly snatching it out of the water. Yianni was lost in a deep reverie in which he imagined himself fishing alongside Pete Splake when he was quickly brought back to reality by Kayo’s thundering greeting.

“Johnny, get your gun! Johnny, get your gun!”

Kayo was the gruff caretaker of the city dump and had taken to teasing Yianni about getting drafted if he didn’t go to college next year. Kayo added to his meager pay by setting aside items like scrap iron, copper tubing, old tires that still had decent tread on them, and various pieces of broken furniture that he could repair. He was also a wicked pool player and was known to run the table on many unsuspecting young airmen from K.I. Sawyer who lost their hard-earned cash because they had mistakenly underestimated Kayo’s skill based on his scruffy appearance. He really wasn’t here for food right now as much as he was to learn the time and location of tonight’s poker game. Unfortunately, Kayo’s pool skills did not extend to poker, where he regularly lost most of the hustle money from his various enterprises, but he just couldn’t resist coming back for more.

Kayo’s teasing unwittingly turned out to be on the mark, but not in the way that Kayo had intended. Yianni wasn’t worried about the draft at all, but about college, and whether he should even apply. In fact he often thought about enlisting in order to escape the conflict between his love for writing and the constant push by his high school teachers and principal to pursue a career in engineering. These well-meaning teachers were going on his stellar grades in science and math courses, but they failed to recognize that most of his success was due to fluency in Greek which, combined with four years of high school Latin, enabled Yianni to know most of the terminology without ever studying. His parents, of course, sided with the school because they feared that writing would not lead to any kind of job opportunity.

Sam and Angela were well aware of the notebook in which Yianni kept recording ideas for a proposed book, and they were troubled by his fierce determination to keep it as a private journal. It wasn’t so much that they feared any kind of deep, dark secrets as much as the fact that it had become a barrier between them. They recognized that their son was bright and were quite proud of his achievements, but they also knew that he was very impressionable and tended to daydream. They worried that he was living in a fantasy world and that he was not developing an appreciation for how the real world worked.

Yianni would readily concede that he embellished the events he wrote about, but the journal served as his laboratory for trying to understand what makes people tick and how their lives had unfolded to this particular point. It helped him realize that each of us had many possible futures and provided glimpses of how his own life might evolve. Therefore, he would never believe that his writing represented a flight from reality or that he was out of touch with the real world.

To the contrary, Yianni knew intuitively that it would be a colossal mistake to become the prisoner of someone else’s expectations, no matter how well intentioned and loving such advice might be. After months of agonizing about college, he was pleased that an exciting idea had emerged.

Yianni would submit a portion of his manuscript to a major magazine as a way of finding out if he should continue to entertain thoughts of a writing career, and if his short story was accepted, he could use it as leverage about what major to pursue. If not, he knew that engineering school would not be the right thing to do and Kayo’s scenario would come true after all.

He could already hear the furor that would be unleashed by his parents if he were to enlist in the Army, but a new confidence now fueled his determination to hold his ground. Perhaps the fates would be kind and he might never have to cross that bridge. In any case, he was ready to roll the dice, certain that either course of action was better than remaining in limbo.

John Argeropoulos is an emeritus professor and former career counselor at Northern Michigan University, where he was employed for 31 years. John also coordinated the effort to establish the Northern Center for Lifelong Learning at NMU, a program that he and his wife (Mary) continue to enjoy in their retirement. Among many published articles, he has written on the history of the Greek community in Marquette County in Harlow’s Wooden Man journal for the Marquette Regional History Center.

A Geology Geek Finds God

by Leslie Askwith

One Friday afternoon, the health department where I worked got a call from a woman on Drummond Island. Her family had rented a house for a reunion. She said everyone arrived feeling good and ready to relax by the river, but soon were moaning and running for the bathroom. People at the resort next door were getting sick too. Nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting were the miserable symptoms. She suspected it was their water.

I agreed with her. The island is known for its limestone, which is notorious to people in my line of work for cracks and fissures, open channels to the aquifer. A limestone ridge called the Niagara Escarpment juts from the earth in that part of the Upper Peninsula. It extends from Chicago to Niagara Falls and, not far west of the island, forms the largest cave system in Michigan near the village of Trout Lake.

I poured fluorescent dye into the toilet tank of the house, and the next day, dye flowed out of the house’s taps. The septic tank had been installed directly on limestone bedrock and it leaked. Sewage was flowing through cracks in limestone to wells nearby.

I worked as an environmental health sanitarian at the Chippewa County Health Department, granting sewage and well permits, and it was my job to prevent contaminated sewage from reaching groundwater. Every spring when builders started clamoring for permits, I set out in my rusty Pathfinder, driving to isolated corners of the county to figure out if and where and sewage disposal systems and wells could be installed. My work Bible was a hugely under-appreciated treasure trove of maps of the county’s 63 types of soil—302 pages of aerial photos marked with squiggly lines delineate soils with names like Halfaday Sand, Beavertail Muck, and Rudyard Silty Clay Loam, which is different from Pickford Silty Clay Loam.

I LOVED my Soil Survey of Chippewa County, Michigan. It stripped the land of vegetation, revealing naked layers of glacial debris, muddy lake bottoms, and ancient coral reefs. I’d haul out my Soil Survey (it’s thick and heavy enough to require hauling) to see what kind of soil would probably be there. A man who worked on the survey said he and others had walked the county with a hand auger, drilling holes every 50 feet or so until the entire county was mapped. Chippewa County is 1558 square miles of land, and even taking the possibility of exaggeration into account, that’s a lot of holes.

I often met Cliff Tyner on Neebish Island. He’d lean on his shovel near me, chewing on a toothpick, wearing what looked like the same faded blue denim shirt with a bright blue X on the back under his suspenders. He’d spent a lot of backhoe time building drain fields for summer homes. “Schoolteachers from down below, puttin’ up an A-frame shack,” he said one time as I struggled with my auger to get through the rocky soil on Rue des Roches (Road of Rocks), slapping at mosquitoes. The St. Mary’s River streamed past, glistening like a silver stream of mercury. Waterfront property was, still is, in demand. People liked the high lots on that stretch of road.

I dug through the glacial till, unearthing smooth rounded stones, evidence of having spent time in the glacial tumbler that moved across Chippewa county 10,000 years ago. Digging these holes throughout the county was a great geological puzzle, a geo-archeological dig. I was the first person ever to see these ancient stones. It didn’t matter that none of them were likely to be valuable. It only mattered that I was the first to ever see them. Who knew what would be unearthed? There aren’t many things that can be said about that even in the sparsely populated eastern Upper Peninsula.

I was looking for a pocket of good soil deep enough to clean sewage before it got into the river or nearby wells. The regulations were specific…six feet of soil that’s dry year-around, porous enough to let the water through, but not so full of open spaces that the soil particles can’t do their work of wiping out viruses and bacteria. I pinched the dirt, felt for sandy grit, tested the clay content, watched for the stain of silt on my fingers and mottled stains in the soil indicating seasonal high water. Fortunately for the owner of the lot on Rue des Roches, the glacier had left behind suitable deposits.

Back at the dock I waited for the ferry, dangling my itchy feet in the river, sitting on a jagged boulder of limestone that had been blasted from the river to make the Rock Cut, a channel deep enough for ocean freighters. I picked up a bit of white limestone containing the imprint of a small mollusk that died 500 million years ago. It felt like a tiny grave in my hand. It was distressing to know the road commission ground that ancient graveyard into road gravel.

I realize this point of view mystifies most people, except for those who love the TV show, The Big Bang Theory, as I do, and who also think the writers are missing out by not including a geologist.

I had a favorite fossil on Drummond Island’s Maxton Plains. Most common fossils are small bits of coral or shell, but this was a good-sized squid-like creature called Orthoceras. The plains are like a giant flat limestone parking lot, a cemetery for dead creatures that settled quietly to the bottom of the ocean that covered the area millions of years ago. Last time I looked for it, the Orthoceras was gone, probably chipped from its grave by someone. Cretin! They couldn’t have gotten anything more than a bit of broken shards.

There’s a slim chance I wasn’t looking in the right place. But the plains draw a fair number of visitors and some people can’t seem to let nature just be. The Nature Conservancy erected signs explaining the flora, fauna, and geology, pleading for people’s respect. The arid rock provides a rare alvar habitat where only plants specifically adapted to the harsh climate of a naked stone surface survive. Delicate tiny herbs, lichens, and mosses find root-holds in the small fissures or, surprisingly, thick fleshy green-colored algae swell in the spring snow melt and rain that collects for a brief time in shallow depressions.

I liked the eerie surprise of happening upon a landscape left exactly as it was when the glacier left. Chattermarks show where hard rocks were dragged across the limestone surface, gouging out parallel crescents like phases of the moon. Some of these hard boulders remain, dropped across the plains 10,000 years ago but looking as though they were scattered last week. Some people, unable to resist leaving their own personal mark, apparently feel that they can improve on this wild landscape by stacking rocks into cairns. These unnatural changes jar like jolts of electricity, spoiling the natural beauty. The building of cairns is anathema to the “leave no trace” philosophy and is even illegal in Norway.

Ken Hatfield, a former geology professor at Lake Superior State University, understands geology geekism. One afternoon we sat in his living room overlooking the broad St. Mary’s River. Ore boats moved slowly by and I felt the thrum of their engines as vibrations moved through the water and wet soil under the house. But what we marveled at was the fact that 10,000 years ago we would have been sitting beneath a mile thick layer of ice, so heavy that the earth is still rebounding from its weight, rising a foot per century. Astounding!

Much of Chippewa County is defined by that glacier. Its melt-water left a county so flat that the sky is the most remarkable scenery. The land was the bottom of great lakes where layers of silt settled sometimes hundreds of feet deep. It’s fertile and grows good hay. New green grass sways and ripples like waves at sea. In mid-summer the hay is cut, rolled into fat round bales and shrink-wrapped in long caterpillar-like tubes of gleaming white plastic.

In early spring, water sits on top of this dense ground in shallow spring ponds that attract flocks of Canada geese and Sandhill cranes. If a field is left uncut, water-loving rushes and willows take over. This clay, technically silty clay loam, is so sticky that it’ll suck the boots off anyone crazy enough to try to walk on it. Years ago a brick-making plant in the village of Rudyard made good use of this clay.

In winter, storms blow deep drifts across I-75, terrifying drivers when visibility is reduced to zero. On calmer days, snowy owls watch for mice from the tops of fence posts, glaring like small angry pillars of snow.

My father-in-law, Elmer Askwith, who grew up on that clay land, remembers how his bedroom window rattled when the wind raged across the open plains, blowing fine licks of snow onto his bed and floor. Elmer was seven when his family’s well was drilled in the early 1920s. He remembered the hiccuping put-put of the driller’s steam engine and the fact that the borehole went down through 300 feet of clay before it hit water. Water, under pressure from the clay above, gushed out of that hole in a non-stop stream. The well flowed for the next 75 years at least, continuing after his old home slumped away from that northwest wind and settled into the weeds.

One morning, news reached the health department about a flowing well that had gotten out of control. In trying to drill his own well, the home owner hit an aquifer under such intense pressure that it produced a geyser like air rushing out of a popped balloon. We all rushed out to the site, having heard exciting horror stories about out-of-control flowing wells. By the time we got there, the geyser had settled down but water continued to bubble from the ground, creating a lake among the trees and soil so soft that we feared the cabin might disappear into a giant sink-hole.

The Munuscong River flows through these clay flats, draining the fields eastward toward the St. Mary’s River. The poet Stellanova Osborn calls this river and other rivers, ditches, and areas of run-off, “fountains eternal.”

I kayaked the river one summer afternoon, a lovely quiet ride, pushed along by the gentle current, experiencing a small flurry of excitement through faster ripples over fallen trees. The river was bordered on both sides by high banks, some showing the bare soil of newly eroded clay. The river was brown and dense with silt, too cloudy to see even a few inches below the surface.

One depression-era winter, Elmer worked on the St. Mary’s River crew south of Sault Ste. Marie. It was a miserably cold job. By day, he helped map the river’s depth, which changed as currents shifted silt on the river bottom, possibly obstructing shipping channels. At night, he slept in a canvas tent along the shore of the river, trying to stay warm under a thin blanket. The ten or twelve miles home was too far to drive twice a day, but he was grateful for the work.

Limestone, sometimes a repository for oil, sits below the clay in much of the county. That fact interested oil speculators in the early part of the twentieth century. They drilled exploratory oil wells on Neebish Island, St. Ignace, and especially in Pickford. “Day after day, week after week, the drilling progressed. Deeper and deeper went the hole. The village and surrounding population was aquiver with expectation. Down and down they went, one hundred feet, two hundred, then five hundred, then a thousand feet. Suspense was building up to enormous proportions.”

The borehole cut through 119 feet of 10,000-year-old red glacial clay…through 128 feet of 405 to 425 million-year-old Niagara dolomitic limestone…through 265 feet of 500 million-year-old blue and black Ordovician shale…through 275 feet of white limestone…and 700 feet of Cambrian red rock up to 600 million years old. At various levels water poured forth in such quantities that the pounding of the drill amounted to little more than a common hammer blow.

Finally, drillers encountered “warm blood red” water under such pressure that it spurted twenty-five feet into the air, a water-spout visible throughout town. The water’s pressure crushed the casing 1300 feet below grade. Thus ended the great search for oil. But the well continued to gush water for the next hundred years, turning the ground around the well into a marshy wetland.

Tales of oil continued. “The oats I gave my horses for dinner were grown on our own farm and when the horses tried to chew them the oil oozed out of the grain,” one grammar school student reported. And at least two farmers found the “black soapy substance that is characterized by oil men as the oil bearing substance” not far below the surface of their land. Not too many years ago, a local well driller encountered a pocket of crude oil in limestone. He filled one fifty-five-gallon drum before it petered out. He brought a Mason jar of it to our office. It looked exactly like what I poured into my lawn mower.

The glacier left stony ridges and also ponds that slowly become boggy swamps. I evaluated one such swamp bought by an excited new landowner who’d bought a hundred acres of this forested wetland. I stepped off the road and sank into soft sphagnum moss. Water covered my boots. We walked around, dodging spindly black spruce. Not hopeful signs for a drain field. I’d found a possible spot in my Soil Maps, a high ridge along the Waiska River. To get there we walked a half-mile along an old logging road over and around boggy ponds black with tannin and organic matter. A great blue heron balanced on a skinny leg and followed our progress with one yellow eye, head feathers erect and quivering. Mosquitoes pestered us, as usual. Eventually we found the ridge with soil that met the requirements, but the logistics of developing the site may have been too much. I never heard that he did anything with the property.

I was driving on a lonely road at the north side of Drummond Island on September 7, 2007, the day after the great opera singer Luciano Pavarotti died. The road was exceptionally rocky, hardly a road at all. Boulders and pools of water threatened my Pathfinder’s undercarriage. I’d visited my Orthoceras (it hadn’t been chipped away yet) and was headed toward an obscure beach strewn with peculiar chunks of limestone pitted with smooth holes.

Engraving - Porcupine Mountains

A red-tailed hawk soared low over the open limestone flats, looking for mice. A pair of Sandhill cranes stalked stiff-legged. I passed a dead snake so turquoise blue that the color seemed impossibly luminous. Heavy clouds glowered in the western sky and leaves of poplar trees shimmered frantically like the spangles of belly dancers. The air felt tense with the anticipation of a storm. The road entered a dark forest with green lacy ferns rising from a welter of fallen tree trunks just as NPR began playing the old recordings of Pavarotti. His perfect voice soared from the radio and my beloved Pathfinder felt like a cathedral, surrounded by shuddering trees, ancient and new life and death, and the coming storm. It truly felt like I was in the presence of God.

Leslie (Piastro Eger) Askwith has lived in the U.P. since 1976, working at the Marquette Mining Journal and Sault Tribe newspaper Win Awenen Nisitotung, and as a freelance writer for Traverse Magazine and Lake Superior Magazine. She published her own newspaper, Homegrown, for which she won a Communicator of the Year Award. She was the first writer-in-residence at Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park and won the Nature Writers of the Upper Peninsula contest in 2015. She recently completed a book called Thunderstruck Fiddle: The Remarkable True Story of Charles Morris Cobb and His Hill Farm Community in 1850s Vermont. She lives in Sault Ste. Marie and can be reached at [email protected]

Silent Night

by Larry Buege, 4th Infantry Division 1967-68

Spider touches my shoulder and instantly I am awake. “It’s two o’clock,” he says.