U.P. Reader -- Volume #5 E-Book

5,98 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Michigan's Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure trove of storytellers, poets, and historians, all seeking to capture a sense of Yooper Life from settler's days to the far-flung future. Since 2017, the U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.'s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The forty-one short works in this fifth annual volume take readers on U.P. road and boat trips from the Keweenaw to the Soo. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about. U.P. writers span genres from humor to history and from science fiction to poetry. This issue also includes imaginative fiction from the Dandelion Cottage Short Story Award winners, honoring the amazing young writers enrolled in all of the U.P.'s schools.

Featuring the words of Karen Dionne, Barbara Bartel, T. Marie Bertineau, Don Bodey, Craig A. Brockman, Stephanie Brule, Larry Buege, Tricia Carr, Deborah K. Frontiera, Elizabeth Fust, Robert Grede, Charles Hand, Kathy Johnson, Sharon Kennedy, Chris Kent, Tamara Lauder, Teresa Locknane, Ellen Lord, Becky Ross Michael, Hilton Moore, Gretchen Preston, Donna Searight Simons, Frank Searight, T. Kilgore Splake, Ninie G. Syarikin, Tyler Tichelaar, Brandy Thomas, Donna Winters, Annabell Danker, Kyra Holmgren, Nicholas Painer, and Walter Dennis.

"Funny, wise, or speculative, the essays, memoirs, and poems found in the pages of these profusely illustrated annuals are windows to the history, soul, and spirit of both the exceptional land and people found in Michigan's remarkable U.P. If you seek some great writing about the northernmost of the state's two peninsulas look around for copies of the U.P. Reader.

--Tom Powers, Michigan in Books

"U.P. Reader offers a wonderful mix of storytelling, poetry, and Yooper culture. Here's to many future volumes!"

--Sonny Longtine, author of Murder in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

"As readers embark upon this storied landscape, they learn that the people of Michigan's Upper Peninsula offer a unique voice, a tribute to a timeless place too long silent."

--Sue Harrison, international bestselling author of Mother Earth Father Sky

"I was amazed by the variety of voices in this volume. U.P. Reader offers a little of everything, from short stories to nature poetry, fantasy to reality, Yooper lore to humor. I look forward to the next issue." --Jackie Stark, editor, Marquette Monthly

The U.P. Reader is sponsored by the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA) a non-profit 501(c)3 corporation. A portion of proceeds from each copy sold will be donated to the UPPAA for its educational programming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

U.P. Reader

Volume 1 is still available!

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure chest of writers and poets, all seeking to capture the diverse experiences of Yooper Life. Now U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.’s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The twenty-eight works in this first annual volume take readers on a U.P. Road Trip from the Mackinac Bridge to Menominee. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and eBook editions!

ISBN 978-1-61599-336-9

www.UPReader.org

U.P. Reader: Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World —Volume #5

Copyright © 2021 by Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA). All Rights Reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

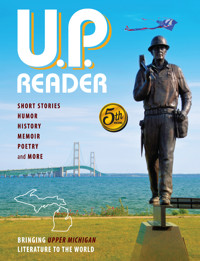

Cover Photo: by Mikel B. Classen.

Learn more about the UPPAA at www.UPPAA.org

Latest news on UP Reader can be found at www.UPReader.org

ISSN: 2572-0961

ISBN 978-1-61599-571-4 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-572-1 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-573-8 eBook (ePub, Kindle, PDF)

Edited by- Deborah K. Frontiera and Mikel B. Classen

Production – Victor Volkman

Cover Photo – Mikel B. Classen

Interior Layout – Michal Splho

Distributed by Ingram (USA/CAN/AU), Bertram’s Books (UK/EU)

Published by

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

CONTENTS

Your Obit by Barbara Bartel

A Little Magic by Binnie Besch

Deal Me Out by Don Bodey

How to Hunt Fox Squirrels by Don Bodey

The Fairy in a Berry Can by Craig A. Brockman

The Walk by Stephanie Brule

A.S.S. for State Slug by Larry Buege

A Matter of Time by Tricia Carr

The Lunch Kit by Deborah K. Frontiera

Alphabet Soup by Elizabeth Fust

The Rescue of the L.C. Waldo by Robert Grede

A Night to Remember by Charles Hand

Feeling Important by Kathy Johnson

Blew: Incarnation by Sharon Kennedy

Thomas: Fortitude by Sharon Kennedy

The Spearing Shack by Chris Kent

Death So Close by Chris Kent

Right Judgment by Tamara Lauder

That Morning by Tamara Lauder

My Scrap Bag by Teresa Locknane

Another COVID Dream by Ellen Lord

Guillotine Dream by Ellen Lord

Sumac Summer by Becky Ross Michael

Requiem for Ernie by Hilton Moore

A Dog Named Bunny by Hilton Moore

Old Book by Gretchen Preston

Calamity at Devil’s Washtub by Donna Searight Simons and Frank Searight

upper peninsula peace by t. kilgore splake

holy holy holy by t. kilgore splake

A Luxury by the Michigamme River by Ninie G. Syarikin

Morning Moon above Norway by Ninie G. Syarikin

A Poetic Grief Diary in Memory of My Brother Daniel Lee Tichelaar by Tyler Tichelaar

Waves by Brandy Thomas

My First Kayak Trip by Donna Winters

Karen Dionne Interview – The Wicked Sister with Victor R. Volkman

Memoir as a Healing Tool by T. Marie Bertineau

U.P. Publishers & Authors Association Announces 2nd Annual U.P. Notable Books List

Young U.P. Author Section

The Dagger of the Eagle’s Eye by Annabell Dankert (1st Place, Jr. Division)

The Treasured Flower by Kyra Holmgren (1st Place, Sr. Divison)

The Imposter Among Us by Nicholas Painter (2nd Place, Sr. Division)

Ash by Walter Dennis (3rd Place, Sr. Division)

Help Sell The U.P. Reader!

Come join UPPAA Online!

Your Obit

by Barbara Bartel

I wrote your obituary today. I’ll read it to you later. Other than that, my morning was uneventful. Did you know there’s an actual formula to writing an obituary? I’d never noticed before reading a handful in the newspaper so I’d know what to write in yours. I think most people only read the entire obit of relatives and friends. Otherwise they read the name, date of birth (to know the real age of the deceased), check for the cause of death to make sure it’s nothing they personally are afflicted with, then scan down to the time of the services. That’s what I usually do. Who cares if someone was a member of the Daughters of Isabella, taught piano, or loved to knit? What people want to know is which brothers and sisters are still alive, who they married, where they live now and what funeral home or church to send flowers or cards. Most folks know where to bring a casserole.

You’ll have to pick a photo to run beside your obit. Please don’t defer this chore to me. Just don’t choose your graduation picture. Remember your mom insisted on giving you a Toni’s Home Permanent with those tight pink hair curlers the night before? I shouldn’t laugh but all the girls in our class thought it was so bold of you to wear a hat for your photo shoot. They called you a Feminist. A woman’s libber. A rebel. Here your blond natural waves had been fried to brittle clumps. You smelled like ammonia for weeks! I hope you pick a photo of you now or very recent. One that captures the crow’s feet and laugh lines you earned.

Oh, in the opening line I wasn’t sure how to handle the God issue. I know you spent most of your adult life searching for meaning and with your scientific mind set could not “believe” as they say. All the redundant phrases like “meet her savior”, “joined the Lord” or “went home to Jesus” would be insulting to your intellect. I don’t like the fragment “passed away”. That sounds so trivial. Cars pass. Clouds pass. Gas passes. Also, it implies you went some place. We’d had the ‘where do you go when you die’ conversation throughout our life together. There was never a conclusion we agreed upon.

So I made a list of ways to describe your, uh, exit, departure, expiration, but none of them fit. I decided to not sugarcoat the fact. I wrote that you died, plain and simple. I can add the date later, when I know. I didn’t include your middle name; you hated the aunt you were named after, how when you were little she made you wash your hands before you could play her piano, an upright, for crying out loud.

Knowing how you feel about your father, I left him out of the second paragraph. Wrote you were the daughter of Genevieve Starling, life-long resident of Summit County. Why mention the asshole that molested you as a child and screwed up your entire life? Thank goodness you won’t have to be buried next to him.

You’re going to have to tell me if you want both your brothers listed. I know that the oldest one is only a half-brother (of a different mother, as the kids say today) but he was always the nicest to you, right? He helped you move several times; you kept in touch over the years. I’m not including Davy. Let him rot. Any brother who steals his sister’s car to use when he robs a gas station should automatically not be included in anyone’s obit. I figure your mom is going to read this and why cause her more heartache. She’ll be dealing with your death and shouldn’t have to be reminded that her bad blood son is still in the state pen. Mentioned your sister since she is respectable but I only listed her most current husband.

If people want to know the entire list of husbands they can look them up at the courthouse. Who cares anyway? Some of those guys she married were very good men. We all know she is a nut case. But I put her in because you guys always had a way of forgiving each other and letting go of the past. I listed her kids with all their last names, too. Her kids are her best work, don’t you think? They haven’t hounded us for any of your tools or other possessions like some of the other insensitive family vultures.

There are too many uncles, aunts, and cousins to list and they know who they are. They don’t need their names in the newspaper. Some of them may appreciate not being listed. I am sure Donny wouldn’t want any bill collectors to know he’s still around. After the family paragraph comes the education and adult life part.

If you read other people’s obits they write where they went to high school, college; some people mention places of employment. This one stumped me. Do I really list all the jobs you had? Would you want the world to know you ran away with a draft dodging trucker your first year in college and ended up in that “art” film? Or how you spent that year backpacking in Europe as a “translator”? I really didn’t know where the adult part of your life started.

When we first met and hid our relationship from our parents or when years later we started living together as roommates? As I reviewed the decades it became harder and harder to put importance on the roller-coaster ride of life together. Mostly we just got by, lived from check to check, scrambling to take a short vacation here and there, with and without the kids. How can I ever put all those years into a couple lines that would make sense to anybody but us? Who else would understand how exciting it was for us to open the front door to that shack bungalow we bought for back taxes from that alcoholic book salesman? Or what it was like to stand in the snowbank outside freezing, our teeth chattering, while watching the place go up in smoke two years later after that pretend-to-be electrician left a live wire exposed in the fuse box on the kitchen wall? Remember the good job you got with that non-profit outfit run by the lusty butch Mennonites who kept asking you to lunch? Who would understand how hard it was living in a lower duplex in the inner city when we couldn’t let the kids off the porch? Little Ruthie still talks about those days. She wasn’t five when we got out of there but she remembers gunshots down the block at the Seven Eleven. No one would believe all we’d survived in those early days. I left it all out. Each thing I thought of just flooded more and more pictures into my mind. I couldn’t select any one to represent you. None of them are who you are today, now. But each one made you who you are, now. That’s the truth.

After the education and job section comes where people list the person’s hobbies and organizations they belonged to. Like if you’ve been a 4-H leader for eighteen years or a church lady, you’d mention it. What does it matter? If you taught the blind to see, hey, go for it, write it down. Most of us normal folks don’t have anything unique or exceptional is how I see it. If you didn’t cure cancer or write a bestseller, I can’t see including anything. Who cares if you collected salt and pepper shakers to sell on eBay? I can guarantee you that the only person interested in your salt and pepper shakers is the burglar reading the obits to see when your house will be vacant during the funeral services so he can help himself to your collection.

I got to thinking about what I will remember forever about you, not that you were born under the sign of Leo, or that you had the thickest, straight natural blond hair in the world, but that you were extremely generous. I’m going to mention how you spent one whole summer of your junior year painting a barn for old lady Courson. Some senior center program hired teenagers to work for old people for three months. You never missed a day out on a rickety scaffold getting the worst sunburn of your life. When you got paid in mid-August (your mom expected you to buy school clothes and you’d at first wanted to buy that beat up green Firebird at Loco Motors) but you surprised everyone by going over to the courthouse and paying the back taxes on Courson’s farm so that the old lady wouldn’t have to go into a nursing home.

Also, I’m going to remember what courage you had. Exceptional courage. Like when you were driving to work, taking Fond du Lac Avenue through the dicey part of the north side, passed the chained up liquor stores, boarded store front churches, and dilapidated grocery stores tied up with wrought iron gates, remember that? Friends would tell you a hundred times to not go down Fond du Lac. At a red light, a skinny woman came running into the street hitting her arm and elbow on the hood of your car with a loud “thunk”. You thought maybe you hit her cause she bounced some. Then you saw she had a broken nose that was spitting blood. One hand held on to the rose colored chenille bathrobe keeping it half closed. She looked directly at you, in your eyes, and you could tell she was terrified. She looked back from the direction she’d come from and there came this tall dude with a wooden baseball bat in his big hand. I’ll never understand how you got out of the car, put your arm around the woman’s shoulders then scooted her into the back seat.

The dude came right up on you and you simply looked him in the eyes and said, “Not today, man. Not today.” You calmly slid back into the driver’s seat and drove off to the hospital with the woman’s screams drowning out the morning traffic report. Your generosity and courage. That’s what I’m gonna remember. Those things and the private stuff I won’t go into.

Following that paragraph, comes the name of the funeral home, date and time of services. I know how you feel about this. You don’t want a funeral home involved in any way. I know, I know, I know. You think I can manage getting your body out to your camp and onto that raised log rack you worked on for the last three years, to offer your body to the elements, returning it to nature. Even with the help of the sons-in-law, I know I cannot grant this last wish. None of us are going to be emotionally capable to conceal your body, load it into the van, then transport it the fifty miles to the camp road and get it on the small trailer behind a four wheeler. I mean, please. Ask me to slit my own wrists, ask me to wear black for the rest of my days. Knowing our family, this final act would turn into a Stooges bungle. There are laws. I cannot fulfill that request. Obviously the obit states, “No service will be held due to the wishes of the deceased.” You will need to come up with another plan for your remains. What’s wrong with cremation? Other than needing to be transported by a funeral home? We could spread your ashes wherever you’d want. Other people do it all the time. Didn’t I tell you that Irv’s granddaughter went on a tour of Lambeau Field last summer and sprinkled some of Irv in the end zone of the famed tundra? I could put you on the fifty yard line behind the Packers bench. Think about it. You’d be there for every home game for the rest of time. Best seat in the house for eternity.

At the very end I’ll suggest in lieu of flowers to send memorials to organizations closest to your heart, like the Sherpa Widows Fund of Bhaktapua, Nepal, the Up In Smoke Medical Research Project at the Veteran’s Hospital, Portland, WA., the Roswell Historical Society, or the Sundance Committee, Lakota Nation, Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

Now that I know how to write an obituary I think I’ll do mine. Or maybe if you’re feeling good enough tonight you can write mine.

Barbara Bartel has been Library Director of the West Iron District Library in Iron River for 27 years, Barbara Bartel earned her B.A. in writing from Mount Mary College in Milwaukee, WI. She enjoys talking about writing and books with friends and patrons, hosting author visits at the library, and cherishes her time with family. She is knee-deep in writing a novel.

A Little Magic

by Binnie Besch

“She’s back in my life and once again she wants to ruin it,” I almost screamed to my friend, Pam. She had called to ask me about a New Year’s party I had attended the day before.

“The party was okay but she’s back!” I knew Pam could hear the upset and anger in my voice as it traveled over the phone.

“Then you better do something quick to stop that.” I could almost picture her shaking her head as she answered me.

“Hear me? Do it now or you might be sorry.”

The day before, that fateful New Year’s Day, had started out innocently enough. Two friends had asked me to join them at a 10 a.m. church service. Chrissy is younger than me by about ten years, has masses of red hair and is a gifted musician. She is also irreverent, bubbling with life, and addicted to knitting. Sarah, who drives a delivery van for a florist shop, is ten years older than me and is my guiding light.

It was New Year’s Day, the start of a new year and a new beginning, and I was feeling optimistic. I would face the New Year with a song in my heart and the Lord in my bosom. I am not overly religious or holier than thou but the offer to attend a church service had been made with an additional lure.

“We’ll go to brunch afterwards at Jerry and Lisa’s and drink Bloody Mary’s and Mimosas,” my friends told me in their efforts to lure me to attend.

The service was lovely. The priest—witty, urbane and a bit of an intellectual rebel who had come to the Upper Peninsula from Connecticut by way of Oklahoma—blessed us with his usual grace during the service and added just enough humor to keep us from taking ourselves too seriously. He dismissed us with the expected farewell blessing, “Go in peace.”

I shivered and pulled my long coat around me even tighter as I left the church and walked towards my car. My 15-year-old beater was cold after being parked outdoors in zero-degree weather for over an hour but it soon warmed up as I drove down back roads deep into the woods several miles north of town. The county snowplows had been out earlier that day to plow even these deserted roads. They’d done their job well and now towering, icy drifts of white disguised local landmarks. Driving was hazardous and it took me almost half an hour to reach my destination. I managed to find a cleared space on the side of the road and parked my car.

“Brrr,” I muttered under my breath as I rushed indoors. I was struggling to remove my coat when a stranger approached me.

“Hi, Franny, don’t I know you?”

The stranger appeared to be in her late 50’s, was at least three inches shorter than me and wore a beige shirt tucked into black formfitting slacks. Brown hair hung to her shoulders and she wore a light application of pancake makeup. It was when she smiled that I noticed her protruding front teeth. Her smile seemed familiar.

“I’m Lexi, Lexi from college,” she said. She paused and a flood of memories tumbled through me.

“Ann Arbor Lexi?” I asked like some kind of idiot.

“Yes,” she said laughing.

“Oh, my gosh, it’s been forty years since I last saw you,” I said. “What are you doing here?”

“We retired and moved here a few years ago to live in my Grandma Irma’s house. Remember it?”

Irma’s house was the site of many beer parties in our youth. Lexi had been infamous for being a good-time girl. If some guys showed up with a few six-packs, Lexi would climb into the back seat of their car with one of them. I was always the one left behind as they’d take off.

At that point our host joined our conversation and offered us drinks. I asked for a Mimosa and Lexi asked for orange juice, plain. Seeing the startled look on my face, she said, “Yeah, I don’t drink anymore.”

She told me that after she’d graduated from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor she had moved to Phoenix, AZ where she’d worked as an editor for various government agencies. She was proud of having taken out a $10,000 loan to purchase a computer in the late 1970s. She’d done freelance software design to pay off the loan. The years passed and she continued working as an editor on the east coast where she met her husband. Lexi then introduced him, a friendly guy of sixty or so with a nice smile.

Together they told me of the first, then second, and recently, the third addition they’d put on Irma’s house. Childless, they’ve filled the house with cats. I am a proud single parent of two grown sons. When asked, I will speak in glowing terms of their accomplishments. But that day these two out-talked me with tales of their cats. One is called “Oky” because they’d adopted him after a visit to Oklahoma. He was their favorite.

I gave them a shortened version of my life during the past forty years. Two unhappy marriages ending in divorce and a broken engagement to a medicine man/shaman. I added my recent downsizing from a teaching job of fifteen years on a nearby Indian reservation. They both asked me a few questions about teaching there. We chatted a few minutes more and then I left the party.

Two days later, shopping at our local supermarket, I stood in line behind Lexi in the checkout lane as she was bagging her groceries. We walked to our cars together but conversation was forced.

“I looked your address up on the internet. Can you see the lake from your apartment?” she asked.

“Only from one room and that’s if you stand in front of the window and twist your head in the right direction to face the lake,” I replied. Our apartment building was the epitome of elegance when it was built seventy years ago but it’s sadly outdated now. We lack a lot of the amenities like air conditioning, microwaves and elevators in favor of one priceless luxury—a lake setting. As tenants we can walk outside and within a few hundred steps we are facing Lake Michigan.

I’d been shopping for bandages that day at the supermarket. I needed Band-Aids, extra-large ones, to cover a burn on my arm.

Hours after I had returned home from the New Year’s Day brunch I was determined to cook a complete meal for myself instead of settling for canned soup or Lean Cuisine. I’d assembled the ingredients for One-Pot Chicken and Brown Rice. I was at the step where instructions directed, “Pour off all but one tablespoon of fat from pot.” I’d picked up the pot and as I attempted to pour the grease into a small can I use for that purpose, the grease splattered up and ran down the length of my right arm burning it badly. I immediately ran cold running water over the burned area for about five minutes and then sat down with a bowl of ice water, ice cubes and a terry towel to ice my arm at regular intervals for the next several hours.

When Pam called me later that evening I told her what had happened.

“How did you know to use cold water and not butter?” she asked.

“Because when I was in college I had a similar accident. I was living with some girls in an old house a few miles off campus. One day I decided to make a casserole but after I lit the gas oven it exploded. I had second-degree burns covering both my arms and burned off my eyebrows and some of my hair. And you know the worst of it? The girls I was living with were mad because I had gone next door to get help from the medical students living there.”

“They don’t sound like very good friends to me,” Pam said. “Who were they?”

“Well, Lexi and Candy and Sue,” I replied. “But once they saw how badly I was burned and that I had to go to Student Health every day for a month to get the dressings changed they forgave me. But Lexi was really mad and didn’t speak to me for days after that because she thought I was hitting on one of the guys. I’d shared my food with her and I know she stole from me and I never said anything to her about it. Worst of all, she hid a shoebox of marijuana under my bed. After I found it she told me it was because she didn’t want to get caught.”

“Caught?” Pam asked.

“She had a regular stream of guys coming in to buy. She didn’t want them to know where it was so she hid it my bedroom and not hers,” I explained.

“Isn’t it funny how you haven’t seen this woman for forty years and the day you see her you burn yourself again. You better take your power—and your life—back from her,” Pam told me.

“How?” I asked her.

“I don’t know but you better figure it out.”

After I hung up the phone I recalled my horoscope for that day. It instructed me to repeat the mantra, “This is my day, this is my year, and this is my decade.” I repeated it several times each time using a stronger voice and emphasizing the words with more meaning.

I learned a lot from my years working on the reservation. I smudged my apartment using sweetgrass and sage. I lit a fragrant braid of sweetgrass and used my hands to waft the smoke throughout each room. It’s better to use a feather but I didn’t have one so I relied on my hands. I had gathered cedar a few months ago and it was now dried. I lit the cedar and repeated the smudging. I spread the smudge smoke throughout my apartment. Then I removed my glasses and “bathed” myself in the fragrant smoke.

I asked the Creator to remove all negativity from my surroundings and from me. I repeated my new mantra, “This is my day, this is my year, this is my decade.” I also asked the Creator to send back to Lexi all the good or all the bad she had created. I asked for the good that she had done to come back to her in increased measure as would the bad. Some might call this a version of that saying, “You shall reap what you sow.” I had learned more from my former lover, the medicine man/shaman, but I had done enough.

During the next several days my burns started to heal and aside from feeling more tired than usual I seemed to be healthy. I was surprised at how New Year’s Day had morphed from a meaningful church service to brunch with friends, where I was reacquainted with someone from my past, to a thorough cleansing (via smudging) of myself and my apartment.

After not seeing her for forty years I was surprised when I encountered Lexi at the supermarket only two days later. But maybe I passed her regularly during the past several years and hadn’t recognized her? She had changed. People always recognize me and tell me that I look the same as I did in high school. I thank them, cross my fingers, and hope that it’s meant as a compliment. We all age differently, that’s how life works.

I often do my best thinking when driving. Pulling up in front of a local shop after I left the supermarket, this thought hit me.

“She now wants your life. You’re single, you have a great apartment, you’re managing financially and you have your freedom. She’s going home to make lunch for her husband. She loves him but feels trapped. Lexi was never one to be tied down.”

“Well,” I added to myself, “this time she can’t hurt me.” I parked my car and entered the shop where I bought myself a few pink roses.

My trusty feng shui book recommended starting the new year by putting in a small pouch dried fruit and nuts to represent a healthy harvest, coins to represent easy abundance, seeds to symbolize fertility, and mistletoe for protection, healing, and a splendid love life.

I thought to myself, “Why not? It couldn’t hurt and it might help.”

It’s now been ten years and I haven’t seen Lexi since.

Deal Me Out

by Don Bodey

The little round guy who used to pastor down the road was selling sweepers now. He had left a business card in the door, and Doug recalled him while he used the card to pry dog shit from the tread of his boots. Familiar dog shit, from the neighbor’s runt-ass mutt. The old lady next door let the dog out at daybreak, and it shit on his mother’s side of the property line every day. He used it for slingshot practice, sent it yelping, but it never quit. It seemed like an insult to his mother.

He hadn’t touched a gun in twenty years, but when he lifted the rifle from the backdoor closet, it felt familiar, comfortable. A gun was a gun; this one might have been his dad’s. He found its balance, put a spot of the linoleum floor in the sights and dry-fired, then leaned it in the corner. No moon. Beyond the short range of the weak kitchen light was a profound blackness that beckoned him to disappear into nothing. He considered it. There was one round in the buckle of the rifle sling, his only chance at shooting his mother a birthday present when it got light.

They had made a deal last night. She was old and ill and trying to die. She had grown up eating rabbit and squirrel and quail, and she wanted one more meal of wild game. Unless the dog was there, squirrels came to the feeder, an easy shot. His part of the deal was to give her that last taste and leave. Her part was to starve to death.

•••

His cigarette smell. Fifty-eight years of living in this house, she could smell every corner of it. He was by the orchard door. No, orchard doors. Until thirty years ago there was a heavy wooden Dutch door there, where their burro hung out, looking in. Ears like upside-down garden spades, voice like a bagpipe. Then D.D. put in them sliding glass doors. The next day she saw the burro walking down the road and never saw him again. Nobody did. But the doors opened a postcard view of the hills from her sink.

D.D. died when Doug was seven and by the time he went into the Army for twenty years, the orchard was giving out too. Now the doors stared out at 25 dead fruit trees that used to make 90 bushels of apples. Ghosts, every one of them.

Still not light, or barely. Like an old picture, darks and grays, no white. She wanted to get sitting up, her birthday. Sit and recollect. She can remember seventy years. River traffic, barges coupled together to make an acre floating down. Bottom farmers at the squat town grocery. Music out of jugs and fiddles. Turtle bakes and harvest carnival. Playing cards with half a deck of cardboard slivers.

Doubledoug is whistling. Like that bagpipe burro, he whistles through his teeth and his nose both so it sounds like two whistlers. Truth is she isn’t sure about the whistling because she often had a whistle between her ears, that goddamn ringing like a hundred thimbles bouncing on a tin pie pan. Sometimes wrapping her pillow around her head and crying sent the ringing away.

But he was whistling.

She meant to listen but she got the peppermint farts. Three months ago, a new medicine made her fart, and they smelled like peppermint, like walking downwind of a green ditch full of wild mint, and after a few soundless ones, she fell asleep in one of those ditches, hearing a calf cry in the distance.

•••

He left a door open an inch and lighted a cigarette, cupping its glow out of habit. From half a mile away he could feel the concussive hypnosis of a long train on the trestle over the river. The birds were warming up in trills; no squirrel chatter yet. He liked sitting here, looking out at where he grew up and left thirty-five years ago. He knew that when light came, that what was left of the orchard would walk out of the black all at once.

Maybe she was awake now. Mornings were the hardest for both of them. She’d need a diaper change and a butt wipe. Two weeks before she had lost all control, and she lost her pride and dignity with it. She had been crying most of the time since, off and on. He almost ran away then; tomorrow he’d go, but it wasn’t running away.

It seemed so light now he wondered if he had fallen asleep. He leaned the rifle in the corner and went to the landing, where he could hear her bird clock chirping off seconds. Except for the clock, there was no sound in her room. The only light came under the drawn shade, which she insisted be five inches above the sill.

•••

She saw the first light and watched a swath come into the room and land on her bed in the shape of a big butcher knife. Now, awake for about the last time, she wanted to remember being a pig-tailed girl farting into the dust of the playground at that dinky school she went to. Maybe she would come back as that girl in her next life. Maybe as squirrel. She felt herself beginning to fart again. She sniffed and couldn’t smell cigarettes. She wondered if he had left.

•••

Mama. Mama.

He couldn’t tell if her covers were moving. When he looked around the room again, it looked full. Her whole frugal life here: cluttered shelves full of pictures of all sizes, some framed and hung on the wall. Many more in piles on the shelves. He found the oldest one of his mom, in pigtails, and one of his dad, and pocketed them. The biggest frame was a bunch of pictures she had taken her scissors to, so it looked like a crowd and she had filled between them with wallpaper snippets; his graduation picture, his wallet-sized boot camp, his mom and dad, dogs and a burro, shoats in the water trough, and his dad’s obituary.

The room was chilly. The wind chimed outside her window tinkled, and the floor board squeaked. He heard her breathe and was turning to go when she called him in a tinkling voice, so weak. There was a vague smell, like candy, when he turned back.

Mama?

I hope breakfast isn’t ready. I want to lie here awhile first.

I haven’t even seen a squirrel; it’s barely daybreak.

Oh Lord, that’s good. I want another of them red-striped pills. Golly, but sunrise is a happy red.

Then he saw what she did. A red, pulsing light came under the parchment shade.

That’s cops, mama.

She felt she was about to die or play dead.

Next door, ambulance, Mama. I’ll watch.

•••

An ambulance was backed up to the porch, but the old dog had already been let out, and was shitting on his mom’s side of the property line. The ambulance beacon made its eyes red, evil-looking. Some inside lights were on. He couldn’t see anyone but somebody was turning lights on in other rooms. The dog hardly moved. Old dog: droop-faced and skinny. He couldn’t tell if it had a tail.

•••

She pulled herself almost to the top of her pillow. Maybe she could make it to the window. Maybe not. So weak. Her muscles have no thickness; feel like binder twine, about to break. All she can do is lie here, listen, pray. She didn’t hear anything from the rest of the house, or from God.

Probably a year ago when she first couldn’t put what she heard together with her brain. So she faked it. She got along that way until Doug came back; then she began to hear again, like a miracle. They had a conversation last night. She felt important and it was the best she could hear for a long time. Now she heard him come to her door. His hand slapped the door casing. His voice sounded like he was the one under covers.

No cops, mama. Downhill neighbor. Ambulance. Some volunteer firemen on the road. Sort of ruins my plan for getting a daybreak squirrel. If you can sleep, we’ll eat in a couple hours. Squirrel and biscuits, but I can’t make the gravy like you. Okay, mama? Want to take a pill?

He looked foggy. Everything looked foggy. She just couldn’t see good enough. But when he sat on the bed, it was real weight, no angel nor devil. Her son. She could feel his hand on her arm, big enough to go around it twice. So opposite of when he was in a crib in this room. She was strong and able and he was like she is now. Except she can think and reason and make decisions, and it is time to give that up. Her part of the deal was not to die before he left. She promised him she would eat again, and he promised she could die where she was.

She thanked him when he brought the pill then watched the slit of light under the shade until the throbbing red slices quit and the familiar yellow of morning emptied into the room. She thought of the neighbor, a woman her age who once stole her clothespin bag.

The pill was working. She was remembering a toboggan ride through an icy field, then into a creek bed breached by winter tree limbs. The remembering switched to a dream, like there was a switch in her pillow, to a hot air balloon at the end of the toboggan run, waiting on her.

•••

The ambulance light quit and two men wheeled a gurney to its back door. A small black car came and both vehicles left after a few minutes. The dog stayed on the property line. No squirrels around the feeder or on the ground. He shot the dog. Head shot.

He started the biscuits. Couldn’t help but whistle. Felt light, less burdened than he’d been feeling. Didn’t know where he’d go, but he would leave today.

Six biscuits underneath foil over the pilot lights. Made him think of a sow’s belly when they butchered. His mom did all the work. Harvest the meat, cure it, eat it. Today he has to gut that dog, dress it, fry it up. His part of the deal. He’d not figured on having to lie to his mother. She wouldn’t eat much anyway. He would if she would, but he wasn’t hungry right now. He changed his whistle to loud and blew Rawhide, which he’d learned from TV, in this house. A happy song.

Mama?

Now the light in her room was pleasing, cool like inside refrigerator light. She was grunting or snoring. The edge of the bed he sat on was damp and wrinkled. Her cover was two quilts sewn together; the bottom one was made from feed sacks from when feed came in colorful bags.

You’re not an angel. They don’t whistle.

Biscuits are raising, getting ready to fry him up. He’s an old rascal. I’ll try some gravy.

She was rolled in the blankets, facing away from him. She didn’t have any hair left on the back of her head. This room had gotten smaller since the last sunrise. Crazy—when he looked at the picture shelf, it seemed like the pictures were looking at him. He looked his dad in the eyes and his dad was here for an instant.

Mama?

One little yellow onion left, boy. Slice it thin. Sautee it till it’s soft and put it in when the gravy bubbles. When the leg muscles will come off the bone easy, put him in the pan, put a tin lid over it on low for ten minutes. Squirrel taste like shrimp. Remember… remember that time? Took a basket to the river fair. Cuts of squirrel on pointed sticks, squirrel-kabobs we said but you called them shrimp cabbage so we sold it that way. Sold out. ‘member?

He couldn’t tell if she was sighing or sobbing. She had told him not to touch her anymore and he was grateful now that she looked like a discarded doll. Over with. They both wanted it over with.

•••

Nothing changed next door. No other cars came. No lights changed.

The dog was a male, sort of. No nuts. Nothing but dog-food-looking-stuff in his gut. His back legs were disproportionately bigger than his front ones and whatever muscles he’d had was now sinew; he broke them into squirrel-size; once he dressed it and put it in salt water, it could pass for a squirrel, except it was pinker.

He found the yellow onion. Her flour was in the same canister, rusty on the bottom, that had held her flour for fifty years. It was one shelf lower than it used to be. He had never made gravy, but it was his part of the deal. He knew where the skillet was. He cleaned the counter, whistled, watched outside, and listened for sounds from her room.

Three cars went down the road, each raising a small dusty cloud and these floated toward the river like three ducklings in a column. The next car slowed until its dust caught up, then turned into the yard and stopped. Panic crept up his back. The rifle was leaning against a porch post, in plain sight. The preacher got out, sort of rolling from underneath the steering wheel. He saw Doug just as he got to the rifle, and raised his arm. He waved back and lit a cigarette. He’d tossed the skin and guts into the weeds, was relieved to see its only trace was a swarm of flies.

Pastor? Hello young man. How’s your ma?

Weak. I’m getting ready to feed her.

Would she be wanting to pray?

She won’t want you in her room. Go around back, to her window, and I’ll tell her you’re here.

Mama?

I been listening. I like your whistling. I hear you rattling pans on the stove, I heard you talking to somebody in the yard.

The preacher, mama, come to talk.

No.

He’ll come around to the window.

No.

From her doorway, the preacher’s belly showed in the slit between the shade and sill but his mom didn’t know he was there until he rapped on the window.

Honey?

The preacher, mama.

When he rapped again, she saw Doug raise the window to even with the shade. Like a cartoon frame, she could see an open coat, the end of a twisted black tie, and a zipper only half way up. He could have had a basketball under his white shirt. The rest of him was a shadow on the window shade. His shoulders weaved like he was trying to balance on a log.

I came because Widow Smith died this morning, but there’s no one there. His voice was soothing; there was some pulpit to it, but it sounded like something from an earlier time.

And since I was next door, I stopped to offer my goodwill. Are you well?

Are you nuts?

Ma’am?

Well, hell, mister. I’m tired. I’m about dead. And I don’t want you peeping in my window when I die. Go on about your business.

Ma’am?

Pastor?

Honey?

Right here. I’m flouring the meat. Seeing the preacher out of here. Need any—

A pill. One of…

Peppermints. Here, mama.

He wasn’t surprised the guy was on the path toward his car, but he didn’t expect to see him smiling so big. When he saw Doug at the doors he cleared his throat.

Never blessed anybody through a window shade. And her… spirit. Makes me feel worthy, son.

Makes selling vacuum cleaners worthy, Pastor. She’s not religious, wouldn’t pray for herself, but if you want to pray for her, that’s your business. I’m making us a meal and I need to tend some biscuits. That’s my business.

•••

The dog was old but lean. He tore off a piece of meat. Chewy. At least it wasn’t a cat or a rat. He put the biscuits in and found a gravy pan; then he didn’t know what to do.

Mama?

I been lying here smelling you cooking. It’s wonderful. Wonderful.

How you make gravy?

I told you.

You told me how to add an onion, but I don’t know how to start. Just tell me like I was a little kid, okay?

She saw him at six years old, standing on a three-legged milk stool at the stove, and told him how to make gravy. In the back of her vision stood his father who would be dead in a year. She tried to hold as much of that as she could. Without touching her, he used the sheets to flip her and clean her then somehow changed the sheets. She kept focused on that vision of him, them.

He had a quick smoke and saw there was nothing going next door, then started the gravy, did it like she told him to. He cut wedges of the meat and added it, then cream and pepper and a tin lid on the skillet. He had done it, done the deal. He tasted it, ladled two scoops over two biscuits.

Ready, mama.

Before he said that, she had been trying to focus on the slit of light but she saw several slits; she knew she hadn’t died because the smell of the squirrel cooking was in the room. But, why so many slits of light? She tried once more to focus. Then he was on the window side of the room, but he was all broken up like a jigsaw puzzle. She tried. She wanted to see him once more. But she failed, and it made her cry.

His instinct was to touch her but he had promised not to. After half a minute her sobs got further apart; then she sniffled.

Honey? Right here.

I am blind. I can only see, I don’t know, like I’m looking at an empty bed with buttons spilled on it.

I’ll feed you.

She wrestled her cover and elbowed her head onto the pillow, opened her eyes when she felt the spoon on her bottom lip, but what she saw looked like the sun reflecting off a pile of broken windshields. The smell of the spoon was so familiar she breathed deep through her nose before she opened her mouth enough to suck the gravy in. Divine. She accepted a few more spoonfuls. Perfect. She could taste it all the way to her stomach. Decades ago, now, the river people gathered for dozens of squirrels cooked in a big kettle over a fire. Everybody danced.

When he came back, he had read her mind.

One more big spoonful, Mama, with a peppermint pill in it.

She felt him looking at her, at her face.

Honey. We did a deal and I’m very happy. Fifty-three dollars under the paper on the bottom of the silverware drawer. Gas money, deal?

Deal.

She opened one eye. Not to see, not to blink. She opened it to close it. She knew he’d see her wink.

How to Hunt Fox Squirrels

by Don Bodey

Many people, especially big-city women, think squirrel hunting is nothing short of cruel, that it consists of carrying some powerful weapon into the woods and looking into the trees until a squirrel pops up like a Pac-Man bug, then bloweee, shoot ‘em dead.

Ain’t no way.

This is how you hunt squirrel. I know, because I’ve been doing it since I was old enough to crap by squatting over a log. Of course, in those days when I first started hunting and shitting over logs I was a boy, and my part of the hunt might only be to carry the squirrels home from the woods. But, nonetheless, I sat many mornings by my old man’s side, us leaning against the same tree, blowing bubble-gum (don’t pop them bubbles, or you’ll have to face the old man’s face, see it turn hard as a hickory knot) I hated bubble gum. In, say, 1955, he was a struggling carpenter and a struggling carpenter’s diversions were things like hunting. And I was nine years old and so it made perfect sense for the carpenter to take his son into the woods with him, teach him a few things.

He taught me to be quiet. By example. Taciturn might be euphemistic in describing his character, and being in a squirrel woods must have been the logical extension of his withdrawal from society. And in a squirrel woods it was acceptable—nay—necessary, to tell your nine-year-old to shut up, to stay shut up. But he taught me other things, important basics of hunting squirrels, and I’m going to teach you.

Get outa the bed. It’s August when the season comes in, and it gets light about 4:30 and squirrels get up at 4:29, so you gotta get out of bed, first off. Usually there is heavy dew down, and that is an important asset to a would-be hunter, because after you get out o’ bed the next step in the scientific system of squirrel hunting is natural, but you must do it in a TOTALLY natural way.

Piss. Be barefooted. Stand, barefooted, in the dewy grass and piss. The reason for being barefooted is to allow the chill of the dew to wake you up (4:30 is not a natural hour), and the reason for pissing is to check the direction of the wind. Look down and you will discover why you don’t need a weatherman to tell which way the wind blows. Your stream may bend to the right or left or it may bend away from you. If it bends towards you, you are likely pissing on your feet, and you are not awake enough yet. When you see which way the wind is blowing you will know which end of the woods to come in from. Enter the woods downwind. If there is no wind, you have struck a perfect morning to hunt because you will be more able to see every movement of the treetops which is caused by the squirrels.