U.P. Reader -- Volume #8 E-Book

6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Michigan's Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure trove of storytellers, poets, and historians, all seeking to capture a sense of Yooper Life from settler's days to the far-flung future. Since 2017, the U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.'s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The sixty short works in this 8th annual volume take readers on U.P. road and boat trips from the Keweenaw to the Soo. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about. U.P. writers span genres from humor to history and from science fiction to poetry. This issue also includes imaginative fiction from the Dandelion Cottage Short Story Award winners, honoring the amazing young writers enrolled in all of the U.P.'s schools.

Featuring the words of John Adamcik, Nancy Besonen, Miina Chopp, Tom Conlan, Nina L. Craig, Art Curtis, Adam Dompierre, Julie Dickerson, Rosemary Gegare, J.L. Hagen, Mack Hassler, Richard Hill, Skye Isaacson, Kathleen Carlton Johnson, Leah Johnson, Larry Jorgensen, Rick Kent, Tamara Lauder, Ellen Lord, Raymond Luczak, Gregory M. Lusk, Beverly Matherne, Maria Vezzetti Matson, Becky Ross Michael, R.H. Miller, Hilton Moore, Mark Nelson, Eve Noble, Alex Noel, M. Kelly Peach, Jodi Perras, Isla Peterson, Jane Piirto, T. Kilgore Splake, Bill Sproule, David Swindell, Ninie Gaspariani Syarikin, Brandy Thomas, Edd Tury, Tyler R. Tichelaar, Analise VerBerkmoes, and Victor R. Volkman.

"Funny, wise, or speculative, the essays, memoirs, and poems found in the pages of these profusely illustrated annuals are windows to the history, soul, and spirit of both the exceptional land and people found in Michigan's remarkable U.P. If you seek some great writing about the northernmost of the state's two peninsulas look around for copies of the U.P. Reader.

--Tom Powers, Michigan in Books

"U.P. Reader offers a wonderful mix of storytelling, poetry, and Yooper culture. Here's to many future volumes!"

--Sonny Longtine, author of Murder in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

"As readers embark upon this storied landscape, they learn that the people of Michigan's Upper Peninsula offer a unique voice, a tribute to a timeless place too long silent."

--Sue Harrison, international bestselling author of Mother Earth Father Sky

The U.P. Reader is sponsored by the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA) a non-profit corporation. A portion of proceeds from each copy sold will be donated to the UPPAA for its educational programming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 511

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

www.UPReader.org

U.P. Reader

Volume 1 is still available!

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is blessed with a treasure chest of writers and poets, all seeking to capture the diverse experiences of Yooper Life. Now U.P. Reader offers a rich collection of their voices that embraces the U.P.’s natural beauty and way of life, along with a few surprises.

The twenty-eight works in this first annual volume take readers on a U.P. Road Trip from the Mackinac Bridge to Menominee. Every page is rich with descriptions of the characters and culture that make the Upper Peninsula worth living in and writing about.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and eBook editions!

ISBN 978-1-61599-336-9

U.P. Reader: Bringing Upper Michigan Literature to the World — Volume #8

Copyright © 2024 by Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA). All Rights Reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Learn more about the UPPAA at www.UPPAA.org

Latest news on UP Reader can be found at www.UPReader.org

ISSN: 2572-0961

ISBN 978-1-61599-810-4 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-811-1 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-812-8 eBook (PDF, Kindle, ePub)

Edited by- Deborah K. Frontiera and Mikel B. Classen

Production - Victor Volkman

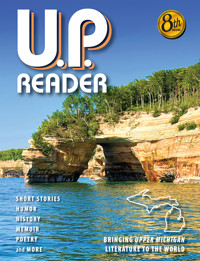

Cover Photo – Victor Volkman

Interior Layout - Michal Šplho (Amorandi Design)

Distributed by Ingram International (USA / CAN / AU / UK / EU)

Published by

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI 48105

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

CONTENTS

About the Cover: “A Pictured Rock Is Worth 1,000 Words by Victor R. Volkman

A Hole in The Bucket by Hilton Moore

Doc Gibson and Professional Hockey in the U.P. by Bill Sproule

yooper haiku by t. kilgore splake

coming home by t. kilgore splake

opening day by t. kilgore splake

Old Friends Having Lunch by M. Kelly Peach

A Walk Along Lake Michigan by Julie Dickerson

A Walk in the Woods by Julie Dickerson

I Want to Say by Rosemary Gegare

Afterglow by Rosemary Gegare

The Hotel Bantam by Adam Dompierre

Taking Care of the Dog by Gregory M. Lusk

The Death of Old 289 by David Swindell

Places Few Have Seen by Tom Conlan

Yellow Eyes by Tom Conlan

Dying in Rural Rockland by Kathleen Carlton Johnson

When It Comes: A Poem for Voices by Kathleen Carlton Johnson

How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm after They’ve SeenMarquette? by Tyler R. Tichelaar

Homage to the Pilgrim by R. H. Miller

The North Country Sun by Raymond Luczak

Jacquart’s by Raymond Luczak

A. Lanfear Norrie School (1917–2016) by Raymond Luczak

Waters of Change by Becky Ross Michael

The Writing Is on the Wall by Tamara Lauder

Dementia Is: by Tamara Lauder

The Good Evening by Maria Vezzetti Matson

Dorothy’s Apple Pie by Ellen Lord

North Country Connection by Ellen Lord

Traveler by Ellen Lord

One Last Chance by Jodi Perras

All Customers Great and Small by Nancy Besonen

Dog Park by Mack Hassler

Our Silent Spring, Read for Friends by Mack Hassler

Chiblow Lake by Richard Hill

Mozambique by Alex Noel

Spring by Alex Noel

Soak by Alex Noel

Two Rivers by Rick Kent

Memories of the Copper Country Limited by Larry Jorgensen

Negatives at a Funeral by John Adamcik

The Faultfinder’s Quarry by John Adamcik

Three Selections from The Seasons, the Years, the Decades by Jane Piirto

The Last Blooms by Ninie Gaspariani Syarikin

When Christmas Changed to Easter by J. L. Hagen

Epistolary Poem by Beverly Matherne

Paranormal or Normal? That is the Question byBeverly Matherne

Haiku for Roger Magnuson by Beverly Matherne

The Opportunity of a Lifetime by Brandy Thomas

Meat by Brandy Thomas

Letters to Harrison #8 by Art Curtis

Wrapped: An Elegy for My Father by Art Curtis

Watercourse by Art Curtis

Baraga County Redemption by Mark Nelson

Rootedness by Nina L. Craig

When Ice Cracks Open by Nina L. Craig

River Gypsy by Edd Tury

U.P. Publishers & Authors Association Announces 5th Annual U.P. Notable Books List

Young U.P. Author Section

Despondent by Eve Noble

Echo by Isla Peterson

Time Deprivation by Analise VerBerkmoes

The Birthday Party by Skye Isaacson

Starved by Miina Chopp

There are No Happy Endings by Leah Johnson

Author Bios

Help Sell The U.P. Reader!

Come join UPPAA Online!

Comprehensive Index of U.P. Reader Volumes 1 through 8

FICTION

A Hole in The Bucket

by Hilton Moore

I was only eight in 1952, too young to understand the term blended family. Of course, even that euphemistic term was far in the future. My father, a Methodist minister, was arm-twisted into taking a charge in the remote village of Nelson due mainly to an indiscretion on his part in the city of Alpena in the northeastern Lower Peninsula. The indiscretion became his third wife, Jeanine. She had two young daughters at the time, Susan and Karen. Father had two young boys, Donny and me, Arthur—Art for short hence the blended family. As for his assigned parish in Nelson, he did not consider his tryst with Jeanine, a married woman at the time, as a self-inflicted wound, despite the evidence to the contrary. I guess you could call that self-delusion as everyone around him knew otherwise. My father was a recent widower at the time, not that it matters now. My mother, Louise, perished in a head-on collision with a snowplow during a heavy snowstorm a year after Father began visiting with Jeanine. Suicide, perhaps? It doesn’t matter now, but at one time it meant a great deal to me. The Methodist Church and the District Superintendent were unforgiving about father’s affair and thought this remote parish was a due penance. My father disagreed vehemently, but it was a lost cause.

Nelson is the county seat, smack dab in the middle of Bishop County. Nelson is a town, maybe a village is a more appropriate word, of around fifteen hundred souls. The village is in the very heart of the Upper Peninsula, and a scant throw away from the enormous waves of Lake Superior when a wicked westerly comes crashing against the miles of rocky uninhabited shoreline. The tourists love it, but the folks who live in this harsh environment know you can’t eat water. Truth is, some locals love it, and some don’t. My father, William Langston, was in the latter category.

I have never thought of the Upper Peninsula in the same light as my father, but I do admit that, for the most part, it is not a bucolic picture at all. Still, there is an innate beauty here if you care to seek it. One must be willing to overlook the abandoned mines, and the anemic second and third growth timber left over after the lumber barons butchered the magnificent white pines, hemlock, and cedar. Of course, these immense forests were stolen from the natives, but hell, that’s all in the past.

My father was, in his own way, a refined gentleman, enjoying fine cuisine and classical music and the better things in life which, as a poor minister in the Upper Peninsula, he could ill afford. William once caustically compared the Upper Peninsula to a third-world country but with more guns and chainsaws. (William was as caustic as ever, and out of his element.)

Reverend William Langston, though he preferred the appellation Reverend Will, owned an old farmhouse with eighty acres of overgrown, fallow land thirty miles from Nelson. The farmstead was on a hilltop about a mile from Lake Superior. On sweltering hot summer days, all of us children would go swimming on the stretch of rocky beach near the farmhouse. To say that this stretch of beach was rarely ever used would be a gross understatement. The major issue was the rocky shoreline that informs part of this story. There was no closer beach for miles, and given our parents’ propensity for gin and tonics, they adamantly refused to drive us elsewhere.

To cast light on this story, Will and Jeanine, preferring to stay at the farmhouse, refused to walk the rocky shoreline, perhaps a hundred feet from the shore. They stayed instead under the shade of the farm’s tin porch roof, made rusted by years of neglect, sipping cold gin and tonics. The Nelson parish was morally conservative, to say the least, and our parents enjoyed being away from the prying eyes of his uptight parishioners.

That brings me to the rowboat. Will and Jeanine were both good parents and were sympathetic about the rocky shoreline, but needed much convincing that the family needed a rowboat. We children, all four of us, argued how a rowboat could take us past the stony shore and out to the sandbar, some hundred feet from shore, where we would still be in shallow waters. We could throw out a cinderblock for an anchor, we reasoned, and use it as a diving platform. Just so you won’t think our parents were negligent about water-safety, there was not a lifeguard for miles, and no one thought the better or worse for it in those days. It may seem incomprehensible now, but at that time, parents didn’t hover over their children like hens.

Because I was the oldest male, and the girls weren’t allowed to drive the tractor, I drove the faded red tractor pulling our rickety farm wagon behind it to the beach, all children aboard. This was before Henry, our rowboat, and fate, intertwined.

We children, William and Jeanine included, were very excited when father bought this faded grey wood rowboat and paid a local resort owner, in cold cash, for delivery at the beach.

Several days later, on a rainy summer day, I safely piloted the ancient Massey Harris down the old road to the beach where we would meet the previous owner and receive custody of our craft. Henry, my nickname for the heavy, homemade, plywood boat didn’t garner any objections from the other children, so Henry it was. The boat was sixteen feet long and painted gunmetal grey, with two old oars. I felt I was justified in naming the boat Henry for a patch the previous owner neatly fixed on the hull. Hence, the name Henry, from the childhood song, “There’s A Hole in the bucket dear Liza, dear Liza,” and the second verse, “Well fix it dear Henry, dear Henry, a hole.” Looking back, fate had its way. As the oldest male child, and despite all maritime history, I just preferred to name the craft with a strong masculine name rather than with a weak feminine name that would not be fitting to the boat. I got my way with what we would now label as toxic masculinity.

A week later, the weather cooperated and the whole family participated in what might be called the christening of Henry. Lisa, the youngest, broke a bottle of Coca-Cola on the bow. Afterward, we carefully picked up all the glass, and forced Henry across the rocky shoreline into the frigid waters of Lake Superior.

This was an all-hands-on-deck process as we half-pulled and yanked the heavy boat to the gentle surf, dragging the old craft into the cold water and out to the sandbar some forty feet from shore. We set a cinderblock as an anchor with old rope, and we swam and played for several hours on Henry. These were blissful moments I will never forget.

Returning Henry to his designation in the barn was another issue altogether. It only took a moment for the entire family to understand we had a problem hoisting Henry’s heavy plywood frame onto the farm trailer and into the barn. With six of us, grunting and groaning, and with herculean effort, the task was completed.

Henry’s paint was beginning to chip and peel, so father mixed some left-over paint that was in the barn that I could apply where it was needed. While the paint didn’t match, it worked fine. I thought, if Henry was a steed instead of a boat, he most surely would have been an Appaloosa. I still believe that Henry liked the comparison.

I should add, that while the previous owner gave Henry a touch-up of paint, he had neglected to adequately paint or caulk the old boat, consequently Henry leaked like the proverbial sieve. I caulked and painted Henrythe best I could, but neither paint nor caulk stuck well on the soggy old boat. I wisely restricted the others from caulking and painting. So, Donny, always head-strong, threw a tantrum, while Susan deliberately turned over a can of old paint. I guess you could call that getting even.

The weather turned grey and wet for the next several days and noisy games of cards and monopoly took up our time. Finally, the weather broke, and we headed to the beach, the small farm-wagon creaking and groaning from the overload, only to recognize we would have the same problem in reverse later in the day when we would need to bring Henry back to the farmstead. All of us children sweated over piles of stones and rocks to get him to the water’s edge. Too exhausted now to swim, we had a problem. We couldn’t just leave Henry at the water’s edge, now that the vessel lay bobbing in several inches of quiet surf. We had to return the water-soaked vessel back to the farm for safe keeping.

I fetched William and Jeanine from their usual back-porch stoop. William, several gin and tonics in, and not pleased to be bothered, drove Missy, our nickname for the tractor, back to the beach with a twenty-foot length of chain and a steel fencepost which he promptly drove into the sand with our old sledgehammer. The family groaned from the effort but eventually dragged Henry up far enough and flipped him over and chained him to the fencepost with a hefty padlock. We children loved Henry but used him only on several occasions that summer, not enough to warrant the effort.

Except me. I would spend hours alone laying on Henry’s overturned grey hull, imagining. Yes, imagining. What? Just everything. Sometimes it was as if Henry were animate.

Occasionally, on starlit nights I would pedal our old Monkey-Ward bike down to the beach and lie on the over-turned skiff, and just gaze at the endless firmament. The constellation Orion was my favorite, and I envisioned myself as a fellow warrior engaged in battle with Canis Major beside us in full attack.

I could sometimes see the magnificent northern lights, flashing and moving like a fire-breathing dragon consuming the dark night by a force larger than life.

Father walked down to the beach one cloudless night and sat down on the over-turned hull beside me. “Are you alright, Arthur?”

“Ya’, I’m alright.”

“You have been coming down here by yourself for nights.”

“Just need time to think.”

“Yeah, I get it,” he paused. “You are afraid that Jeanine and I are divorcing.”

“That’s part of it. Well? Are you?”

“Yes, I’m so sorry.” He muffled a sob and took my hand. “I’ve never been very good at relationships, and it shows.” A cloud moved across the face of the moon and cast a shadow. “As a man it seems I am inadequate in so many ways. The gut-wrenching truth is I am a lousy preacher and a poor example for you boys.”

“Father, you try; no one should ask for more.” I was weeping now.

I suppose this could be, with some minor changes, the end of the story. But it isn’t; this tale would just be a melancholy trip down memory lane if Henry hadn’t arrived in my life. Even as a child, I wondered whether fear precedes premonition. How did I know in a dream-like state that something bad was going to happen to Henry, or was it to happen to me, or my family? Perhaps? And, yet I knew. As an adult, we chalk up such altered states-of-mind to chance, or for the religious, as a sign from God.

On days when it was too gloomy to play outside and the others were all involved in a game of Monopoly, I would go see Henry; yes Henry. We would chat back and forth for hours till I heard the old dinner bell ring. I understand that many folks would say I was just fanciful, or at that young age, perhaps just daydreaming. Or perhaps I was suffering from a form of childhood psychosis?

I realize now, that as a child, my relationship with Henry served several purposes. First, and foremost, it protected me from psychological harm from others or perhaps it protected me from myself.

One rainy day later in the fall, I returned to see Henry. I cried when I saw that someone had dragged the stern into knee-deep water and shot two holes in the vessel’s bottom. He was half-full of sand and water. In my grief I wondered how someone could be so cruel. If I had been there, would I have been a victim too? Is the world run by haters?

“It will be ok,” I heard Henry say in a very quiet voice.

“You will never be the same, and neither will I,” I said with tears in my eyes.

Later that afternoon, William, seeing my distress, tried to patch the derelict boat, but Henry was beyond hope.

As I watched my father, I sang in a trembling voice, “There’s a hole in the bucket, dear Liza, dear Liza. Well, fix it, dear Henry, dear Henry, a hole.”

Straining, all of us working together could not budge the water-logged boat away from the shore to the waiting trailer. Henry’s ignoble remains were later swept away by winter storms.

Whether Henry affected all the other children, I have no idea. Jeanine divorced my father several months later, and I grieved for so many losses. What I am certain of is that the old derelict did impact my life and my younger brother, Donny, as well.

As a young man, Donny, drunk as usual, found out quite by accident who had shot the jagged holes in the bottom of Henry. Drunk, and in a fit-of-rage he murdered this young lad. In my eyes no murder is justifiable, especially in what was most likely a case of juvenile vandalism. Don was sentenced to a term of twenty years to life. After serving twenty-one long years in Marquette Prison, Donny, now a hardened and bitter man, moved to Alaska and worked construction.

As my father lay dying in the hospital, he wanted forgiveness. “For what?” I replied.

“Perhaps, for the mistakes I made.”

“Father, you taught me to follow a path of my own intuition; although at times, I must admit, you stepped off the fucking path into a nasty pile of shit,” I laughed.

“Look at me. I am a successful author and illustrator of children’s books. I credit you and Henry for that. In my younger days I thought that it was my duty to counter hate with love, put evil where it belonged—somewhere in the depths of hell. I could have been a preacher like you, but I knew better. Wasn’t my path. I have come to understand that often hate preys upon hate; it is self-consuming. One must just get out of the way, and hatred, like twisting eagles in the sky will plummet toward earth. Love will always be in the background, and when the battle of life ends, love will always be the victor.

“Father, I am thoroughly convinced that everything I learned about love, I learned from you and Henry. Have no regrets, Father, have no regrets.”

Historical – ishpeming Lake Angeline Mine

NONFICTION

Doc Gibson and Professional Hockey in the U.P.

by Bill Sproule

In the early days of hockey, it was a game for amateurs, and it was not until 1903 that Canadian-born dentist Jack “Doc” Gibson and Houghton entrepreneur James R. “Jimmy” Dee decided to recruit the best players from Canada and openly pay them to play for the Portage Lake (Houghton) hockey team. The team won the 1904 U.S. Championship and defeated a team from Montreal for what was billed as the World’s Championship. Following this successful season, Gibson and Dee began promoting the idea of a professional hockey league, and in December 1904, play began in the International Hockey League (IHL). The league had five teams – Calumet, Pittsburgh, Portage Lake, Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario – and although the league lasted only three seasons, it was the start of professional hockey.

John Lindell MacDonald “Jack” Gibson was born in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario on September 10, 1879, to James and Mary Gibson, who were originally from Aberdeen, Scotland and settled on a farm in Waterloo County. As a youth Jack excelled in school and several sports and won Western Ontario championships in rowing, skating, and swimming. At seventeen, he was a star member of the 1896-97 Berlin-Waterloo team in the Ontario Hockey Association’s (OHA) new intermediate league that defeated the Kingston Frontenacs to win the league championship. In the fall of 1897, Gibson entered the Detroit College of Medicine (now part of Wayne State University) to study dentistry and play on their hockey team. During the 1897-98 season, he also played on a Berlin senior team in the OHA league and planned to travel between Detroit and Berlin for games during the season. However, when the Berlin team defeated its crosstown rivals, Waterloo, in an early season game, the team manager and Berlin Mayor Rumpel rushed out on the ice and presented each player with a ten-dollar gold piece. The Ontario Hockey Association heard about this celebration and ruled that the players were professionals and expelled the team from further competition. Only amateurs “in good standing” were allowed to play in the OHA, and players who received any remuneration were guilty until proven innocent. His season with Berlin ended in early January and although the OHA lifted its suspension at the end of the season, it left a lasting impression. Gibson played three seasons for the Detroit College of Medicine (DCM) hockey and football teams and graduated in 1900. However, while Gibson studied at DCM, he continued to play on a Berlin hockey team, and he was recognized as one of best hockey players in Canada.

John Lindell MacDonald “Jack” Gibson, D.D.S. (Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections)

In the fall of 1900, Gibson moved to Houghton and established a dental practice in downtown Houghton. He felt that this would be a perfect place to start his career as the area was in the midst of a copper mining boom and he had visited Houghton before when the DCM hockey team traveled to play an exhibition game at the Palace Ice Rink in Ripley. A couple of his DCM hockey teammates from Listowel, Ontario also chose to settle in the Copper Country. Dr. Earl Hay opened a dental office in Hancock and Dr. Percy Willson settled in Chassell to begin his practice as a medical doctor. Gibson immersed himself in the Houghton community, joining several fraternal lodges and meeting community leaders though social events, and he soon became known as “Doc” Gibson. In his first winter, he joined the Portage Lake YMCA hockey team. The team included several local players, as well as Dr. Hay, Dr. Willson, and Dr. R.B. Harkness. Dr. Harkness, a medical doctor, was born in Pennsylvania and played hockey in Pittsburgh as a student at Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh). He moved to Houghton in the fall of 1900 and located his office in the same building as Gibson.

Gibson was captain and coach of the Portage Lake team. Charles Webb was the team manager and was responsible for the financial aspects and team operations. The Portage Lake team won the 1901 Upper Peninsula League Championship and local interest in hockey grew as fans packed the Palace Rink to see Gibson and the team play.

Portage Lake YMCA Hockey Team, 1900-01 City of Houghton, Ralph Raffaelli Collection) Standing, left to right: Bert Potter, Ellsworth, E.B. Harkness, Black, Earl Hay Seated, left to right: Wally Washburn, Jack Gibson, Charles Webb (manager), Percy Willson, Peter Delaney Front Row, left to right: Thompson, Andy Haller

As the Portage Lake team prepared for the 1901-02 season, Houghton businessman James R. Dee joined the executive board, and Gibson and Webb started to recruit a few players from outside the Copper Country. Gibson brought in Herman “Dutch” Meinke with whom he had played in Berlin and recruited Joseph “Chief” Jones, one of the best goalies in Ontario. The team played ten games that season against teams from Minneapolis, St. Paul, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Portage Lake was declared Champions of the West after they defeated the Kentwood Country Club team from Chicago, and they then played the Pittsburgh Athletic Club in March 1902 for what was described as the Championship of the United States. Pittsburgh was the Eastern Champion and a member of the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League. It was to be a two-game, total goals series in the Palace. The team split the games and the total goals were equal, so a 1902 United States Champion was not declared.

Gibson and Dee soon realized that if hockey were to grow in the area, a new facility would be needed to accommodate the spectators who wanted to see the Portage Lake team play. In the summer of 1902, Dee organized the Houghton Warehouse Company to build a facility that could be used as a storage warehouse in the summer and serve as a skating and hockey arena from mid-December to late March. The company purchased property on the Houghton waterfront and the building was completed in the fall in time for the winter season. The building had a natural ice surface of 80 feet by 185 feet, and seating for 2,500 hockey fans and room for an additional 600 standees. A contest to name the building was held, and the name “Amphidrome” was selected. While the arena was being built, Gibson and Webb were busy recruiting more players from Canada for the upcoming season. They brought in Joe Stephens, one of Gibson’s teammates from Berlin, and Canadians Fred Lake and Ernie Westcott, who had played for Pittsburgh in the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League.

The Amphidrome opened soon after Christmas in 1902, and the first hockey game was played on Monday, December 29, 1902, between Portage Lake and the University of Toronto Varsity team. The local newspaper reported that over 5,000 attended the first game and it was the largest gathering of people under one roof in the Upper Peninsula at that time. Portage Lake beat the team from Toronto 13-2 and the top scorer was center “Dutch” Meinke as he scored eight goals.

The 1902-03 Portage Lake hockey team was a good team that went undefeated for the season, and they outscored their opponents 146 to 36. Portage Lake played sixteen games against teams from Detroit, Duluth, St. Louis, St. Paul, and Pittsburgh and they defeated the Pittsburgh Bankers for the 1903 United States Championship. Joe Stephens and Dutch Meinke were the season’s top scorers for Portage Lake with thirty-six goals and thirty-four goals, respectively. Following the season, James Dee became President of the Portage Lake team and Gibson felt that the team could be even better.

In the fall of 1903, Gibson and Dee made a momentous decision when they resolved to openly pay players to come to Houghton to play hockey. They realized that to convince top Canadian players to give up day jobs to play hockey for a few months and risk their amateur status in Canada, substantial salaries were essential. Individual player contracts were negotiated and salaries that paid $15 to $40 per week were enough to convince players to take the risk. The best players could attract a salary of $75 per week and salaries would come from dividing gate receipts.

Gibson and Webb recruited several players from the Pittsburgh teams including Riley Hern, Bert Morrison, “Cooney” Shields, and Bruce and Hod Stuart for the Portage Lake team. A group from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan also decided to pay players and several members of 1902-03 Portage Lake team signed to join the Michigan Soo team. Former Portage Lake players included Chief Jones, Dutch Meinke, Joe Stephens, and Fred Lake. The Michigan Soo team also recruited Frank Switzer from Pittsburgh.

Portage Lake Hockey Team, 1903-04 – U.S. Champion and World Champion (MTU Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections) Standing left to right: Fred Westcott (spare), James Duggan (trainer), Charles Webb (manager), James Dee (president), Joe Linder (spare) Seated left to right: Bert Morrison (rover), “Cooney” Shields (forward), “Doc” Gibson (point and captain), Hod Stuart (cover point), Bruce Stuart (forward) In foreground: Ernie Westcott (forward), Riley Hern (goal)

The expectations for a successful season were very high in the community as the local newspapers wrote that the recruited players were among the best from Canada. Because the team was not in a league, exhibition games were arranged, and the schedule evolved during the season. Gibson and Webb wanted to arrange games with the best teams from Canada, but Ontario teams were reluctant to schedule games as they would be banned by the Ontario Hockey Association for playing a professional team.

Portage Lake defeated the Pittsburgh Victorias for the 1904 United States Championship, and as the team was returning to Houghton, there was some talk of submitting a challenge for the Stanley Cup. However, soon after the team arrived in Houghton, Webb received a challenge from the Montreal Wanderers for a two-game series to be played in Houghton. Portage Lake accepted the challenge, and two games were scheduled for March 21 and 22, 1904 in the Amphidrome. The series was billed as the World Championship between the Montreal Wanderers, Champions of Canada, and Portage Lake, Champions of the United States. Portage Lake defeated the Wanderers in the first game 8-4, and according to local newspaper reports, “the game was the fastest hockey ever exhibited in the Copper Country and naturally the greatest game ever played in the United States.” On the following night, Portage Lake defeated the Wanderers 9-2, and the newspaper stated that, “the game had all the features which go to make hockey the most exciting sport in the world.” One of the Portage Lake players was quoted, “We claim to be champions of the world and ready to play any team which disputes our claim to the title and are willing to produce all kinds of money to back it.”

Portage Lake ended the season with a record of twenty-three wins and two losses, and they outscored their opponents 259 to 49. Bert Morrison proved his value to Portage Lake as he scored ninety-four goals and Bruce Stuart was not far behind as he scored seventy-five goals. In Michigan Soo, Frank Switzer scored forty-five goals, while former Portage Lake players Dutch Meinke scored thirty-seven goals and Fred Lake scored twenty-eight goals.

Following the success of Portage Lake, and as the interest in hockey in the United States was growing, Dee wrote Arthur McSwigan and others from the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League about forming a national hockey association or league with up to a dozen teams. Dee indicated that based on his experience with the Portage Lake team, hockey could be a viable business venture and suggested that teams from Canada would be interested. Following months of discussion, James Dee organized an initial meeting in Detroit to determine the interest and prospects of organizing a league that would be known as the “American Hockey League.” Business leaders from several cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Duluth, Grand Rapids, Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Montreal, New York, St. Louis, and St. Paul expressed interest in a franchise but they decided not to proceed at that time. A group from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario was also interested and indicated they would attend the next meeting. In early November 1904, representatives from Calumet, Houghton (Portage Lake), Pittsburgh, Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan (Michigan Soo), and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario (Canadian Soo) met in Chicago and agreed to form a professional hockey league. They adopted the name “International Hockey League (IHL)”, and play would begin with the 1904-05 season. It would be the first professional hockey league in which all players would be openly paid to play hockey. The executive prepared a set of league operating rules and rules that would govern play. It was agreed that each of the teams would play a 24-game schedule with three home games and three away games against each of the other teams. A revenue sharing plan was also adopted.

Daily Mining Gazette, March 18, 1904

Team managers moved quickly to assemble line-ups and put together a schedule for the 1904-05 season. Calumet played its home games at a new Palestra arena in Laurium, and while the arena was under construction, former Portage Lake player Hod Stuart was hired as the Palestra manager and captain of the Calumet team. Pittsburgh’s home arena was the 5,000 seat Duquesne Gardens, while Portage Lake’s home games were played in the Amphidrome. The Michigan Soo team played at the Ridge Street Ice-A-Torium, near the Soo Locks, and the Canadian Soo team played in the Soo Curling Club’s Gouin Street Arena.

As the 1904-05 season began, most newspaper reporters felt that Portage Lake would dominate the league, but Hod Stuart had recruited an outstanding team, and Calumet won the league championship. The team was led by the league’s two top goal scorers – Fred Strike and Ken Mallen - and the league’s top goalie was Calumet’s Billy Nicholson. Portage Lake finished second, and as the season ended, Doc Gibson announced that he was retiring as a hockey player. He was always respected throughout the Copper Country and although he retired as a player, Gibson continued to be involved in numerous events and activities. He played baseball and served as a referee for local hockey and IHL games and was an umpire for charity baseball games. The league operated for three seasons and Portage Lake won the league’s championships in both the 1905-06 and 1906-07 seasons.

During the three seasons of the IHL, hockey changed dramatically as several professional hockey leagues formed in Canada. The Canadian players in the IHL now had the opportunity to return to Canada and openly accept payment for playing hockey and the best players were sought by several teams in a bidding war for their services. The IHL also faced several challenges including a general economic downturn and sagging attendance in a few of the league cities. Teams could not generate enough revenue to offset the operating expenses and payrolls to compete with the salaries being offered by professional teams in Canada. Ultimately, the growth of professionalism in Canada would finish the IHL. Although the IHL operated for only three seasons it attracted the top players of that era who went on to exciting careers in Canada, of which several were later recognized with induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Jack “Doc” Gibson, 1954 (Jim and John Leech Collection)

Jack “Doc” Gibson closed his Houghton dental practice in 1907, moved to Calgary, Alberta, and went into a real estate partnership with Charles S. Mills, a colleague from Southern Ontario who had also moved to Calgary. Gibson and Mills acquired lands in Calgary and rural Alberta for development and later expanded their partnership to include general brokerage, insurance, and loans. However, Gibson did not lose his passion for sports as he was hockey referee and a member of the governing board and president of the Alberta Amateur Hockey Association. He also played football for the Calgary Tigers and was a member when the team won the 1911 Western Canada Rugby Football Championship. During World War I, Gibson joined the Canadian Army, served overseas with the 82nd Infantry Battalion, and then following the war, he returned to Calgary, reopened his dental practice, continued his involvement in hockey, and found many new interests. He was an avid curler, life member and past president of the Glencoe Club and the Calgary Horticultural Society. In 1950, at the age of seventy, Gibson retired from dentistry as Calgary’s most famous dentist, and he died in 1954. For his contributions to hockey, Gibson was one of the original inductees into the United States Hockey Hall of Fame in 1973 and was inducted as a builder into the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto in 1976.

Gibson was not forgotten in Houghton and in 1938, members of the Northern Michigan-Wisconsin Hockey League purchased a trophy for the league’s champion and named it the Gibson Cup in recognition of his outstanding contribution to hockey in its infancy in the Copper Country. The Cup was first awarded in 1939 to the Portage Lake Elks team and today the Gibson Cup is an annual competition trophy between two local senior amateur teams – the Portage Lake Pioneers and Calumet Wolverines.

It has been over 120 years since the first professional hockey league was formed, and how many would have guessed that a dentist from Canada would help to make a small town in northern Michigan the birthplace of professional hockey.

References

Fitsell, Bill. “Doc Gibson – The Eye of the IHL.” The Hockey Research Journal, Society for International Hockey Research, VIII, no. 3, 1 Oct. 2004.

Sproule, William J. Houghton: The Birthplace of Professional Hockey, self-published, 2019. Recognized as a U.P. Notable Book by the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association (UPPAA) in 2020.

Historical – St. Ignace and Mackinaw Island

yooper haiku

by t. kilgore splake

deer season opening day

pasties euchre leinenkugel farts

dreams of seventeen-point buck

wilderness poet’s ghost

welcoming early morning light

through raven’s dark eyes

early upper peninsula autumn

april blizzard storm turning

god’s country all over white

yooper ghost forest shadow

dancing in brown autumn leaves

gray sky shade of winter

feeling alive in world

cliffs shadows beside brautigan creek

poet dancing in wildflowers

coming home

by t. kilgore splake

tranny-tripping early morning

battle creek city limits rearview mirror

steady hum of tires on highway

poet heading true north

crossing mackinaw bridge

returning to god’s country

solitary traveler

imagination in high gear

dreaming of brook trout beauty

campfire cold beers

owl’s warm evening welcome

opening day

by t. kilgore splake

carrying rod and reel

wicker fishing creel

flies attached to canvas hat

soaked in deep woods off

pleasant wilderness afternoon

beside brautigan creek

trophy rainbow dreams

FICTION

Old Friends Having Lunch

by M. Kelly Peach

Mr. Cawley arrives at his favorite open-air café at noon. It is tucked in amongst the red pines and white oaks off of H-03 near highway M-94. He missed breakfast and is feeling quite hungry. On this bright and beautiful, warm spring day, the sky is a blue matching the nearby AuTrain River.

A gentle west breeze wafts the delicious aroma of stewing rabbit to his sensitive nostrils. This is one of his favorite dishes and a specialty of the region. As Cawley walks over, he can see—though advanced in years his eyesight is still very keen—that the table fare is already set and presided over by the nervous owner named Ark. He is a younger fellow, scrawnier and shorter than Cawley. Once Ark understands the new guest is staying, he withdraws warily to allow his patron to dine alone.

Cawley does prefer eating by himself. He is an individual of few words and poor in social graces. He clucks a cursory thank you in the direction of Ark who is now in full retreat. He does his customary survey of the surroundings, sees nothing is wrong, then nibbles a quick taste. He quickly raises his head. No others are in sight. He takes two bites, jerks his head upwards again. Still all clear. He dips his head, continues eating.

The breeze sighs among the lightest green of the early ferns, purple gaywings, and gold-thread flowers. It brings the soapy scent of trailing arbutus to his nostrils, ruffles his glossy black attire. The sunshine finds turquoise and maroon highlights in its sheen as he shifts his torso to and fro in irritation because Ark has helped himself to the eyes, Cawley’s favorite part of the rabbit.

He settles for the guts and hungrily tears into the belly of his rabbit dinner. He enjoys the savory liver and tangy pancreas. After a few bites, his black eyes notice a shadow flitting over the road. He looks up from his dinner and sees a familiar figure approaching.

It is Gluck, a buddy from his youthful days, looking ancient and starved. Cawley’s craw is full, so he merely nods his welcome.

Gluck croaks a greeting as he walks up to his elderly comrade and asks, “May I join you?”

Cawley, mouth still stuffed, nods again towards the food between them.

“Well thanks old pal. Don’t mind if I do.” Gluck then helps himself to the rabbit’s delicious nose.

Cawley gulps down his mouthful of guts and pauses in his feasting to look at Gluck working his way through the rabbit’s flesh along its back. Remembering his friend’s preferences from many a past shared meal, he knows the ribs will be his next goal. Cawley moves on to the meaty hams.

They haven’t talked in years. Cawley is unsure of how to start the conversation. He has made little—well, no effort, really—to keep in contact with Gluck who has made several attempts at communication in the past. These attempts, although kindly received, were never returned. Cawley had convinced himself he was too busy to do so. He had a wife and was helping raise their children, plus the basic business of survival itself. Would this graying companion of his youth be angry with him for ignoring their friendship?

Cawley takes a chunk from the haunch. Gluck is enjoying the delicate rib meat. He doesn’t seem upset; in fact, appears perfectly at ease. Gluck notices he is being watched. Mouth rather full, he responds with a quick nod of the head and a sigh of contentment.

The host, his voice deep and rough, inquires, “Good rabbit, eh?”

His guest agrees, “‘S’excellent.”

Nothing further is exchanged as Gluck finishes off the rib meat on the exposed side of the rabbit in a series of quick and efficient nipping gulps while Cawley demolishes the rear quarter.

Working together, they flip over the cottontail and start in again. Cawley is on the haunch and Gluck on the ribs.

They eat with heads bobbing up and down and side to side. Other than some brittle oak leaves skittering crab-like across the road and a few flies buzzing about, all is quiet.

Cawley moves to his right to begin on the rabbit’s pulverized shoulder. Gluck continues feeding on the shattered ribs.

After a few more minutes of eating, Gluck is feeling almost full. Not wanting to overstay his welcome, he looks at Cawley, bows in solemn dignity, squawks, “Thank you, old friend.” His lunch partner bends in return. Gluck extends his wings and, with a little hop, takes flight to the north.

Cawley swallows his food, slowly tilts his head to look skyward. Though Gluck has already flown too far to hear him, he mutters a husky, “You’re welcome, farewell my friend.”

He continues devouring his lunch, quickly forgets about his companion. Still eating hungrily, he forgets caution, fails to notice a pair of coyotes with silvered muzzles approaching silently along a nearby deer path. Partners for years, they are highly skilled hunters and quite famished.

Gluck, uncertain he wants to head north, has circled around and sees the pair of predators preparing to attack his friend. He emits a croak of direst warning as they rush forward. Cawley springs upwards with wings flailing and manages to evade their snapping jaws by the barest of margins. He flaps his wings in a series of powerful wooshes and is soon flying parallel with Gluck.

Wordlessly, they head south towards a favorite haunt of their younger years. A sandbar in the middle of the river where they can get a drink, wash down the delicious rabbit they shared, and maybe talk about what’s been happening in their lives.

Historical – Marquette lower harbor 1861

NONFICTION

A Walk Along Lake Michigan

by Julie Dickerson

“Many will never see a water-scape like this”, I told him. What a splendid sight it was. Ripples and wind patterns ran all through the snow. A bay full of giant icebergs frozen in the great lake. Every one was composed of shards of sparkling ice, all the pieces tossed together by the erratic wind and waves. Each iceberg was reflecting the sun’s light in a dance of diamonds. And yet, oddly, some areas of the lake were frozen as smooth as a windowpane. The cold must have come so quickly that this area of the lake just stopped its motion as if someone had shouted to it, “Be still”.

And still it is; this huge lake that churns and rolls all summer long. Sometimes just a gentle lap at the shore, other times huge waves crashing as they break. But now, so very silent. The icebergs stuck and the vast bay is one silent frozen mass. No birds, no foxes, no terns, no chatter of the squirrels or croak of a tree frog. A motionless lake of this immensity is such a surprising scene to view. Yes, the air was cold, but the sun shone brightly, and the sky was an azure, summer blue. Everything combined to make one of the most remarkable vistas of natural beauty I have ever seen. Who else saw the lake today in all its winter glory?

NONFICTION

A Walk in the Woods

by Julie Dickerson

It was a day I waited for all winter. Dad could tell it was time by the size of the leaves on the oak trees (the size of a squirrel’s ear!) and by apple blossoms changing from pink buds to glowing white flowers with honeybees buzzing all around them. The day to take a walk in the woods with Dad was finally here!

The farmers would approve of our trek through their fields as it was before planting time. We would have to cross the creek where we saw leopard frogs and painted turtles. The tadpoles had hatched. They were black and tiny, swishing their little tails in the shallows.

At last, we approached the edge of the woods. As we hiked in deeper, the sunlight filtering through the tiny leaves formed a dappled pattern on the ground. I was cheered to be there and looked forward to the exciting days of spring and summer before me.

The first flower Dad found was a Dutchman’s-breeches. I giggled at the funny shape, like fairy pantaloons hanging on a stem. Then there were the bleeding hearts I liked so much, pink and perfect. Everywhere we looked was a fairy land of flowers.

“Look there,” instructed Dad as he led me to a clearing in the woods. Straight ahead was a drift of trilliums as far as you could see. Their white petals were frolicking in the sun, replacing the snow drifts of winter.

Next, we found my favorite, jack-in-the-pulpit. How quaint to see a flower with its own little person inside. Jack was preaching in his pulpit with the curved roof over him; sheltered from the spring showers.

Over in a marshy area Dad pointed to yellow flowers he called marsh marigolds. He explained, “They always like their feet wet.” That meant the roots had to always be moist. Next to the marsh marigolds Dad picked something and rubbed the leaves in his hand. He put the leaves under my nose.

“Yuck!” I said. “It smells skunky.”

“Then it was named well as it is skunk cabbage,” laughed Dad. “You’ll often see it with marsh marigolds.”

Climbing down a tree trunk, a scolding squirrel startled us. We forgave him as he pointed out to us some Trout Lilies at the bottom of the tree. “They’re also called adder’s-tongue. Can you see why?” asked Dad.

I looked closer and saw the protruding stamens looked like a snake’s tongue.

“Now let’s start looking for food,” Dad suggested.

“What? Food in the woods?” I asked.

“Yes, the saying is ‘May is Morel Month in Michigan’. They are the best mushrooms in the world if you ask me,” Dad concluded.

“There are many beliefs about how to find morels, but I have luck under dead elm trees and under apple trees. Let’s look closely at the ground for a while and check for something sticking up through the dead leaves, something that looks like a brain.”

“But Dad, how can we tell an elm tree when the leaves aren’t all the way out?” I asked.

“When you can’t see the leaves, you have to rely on the bark. Elm trees have bark with lots of ridges. Let’s keep looking,” Dad told me.

As we approached a slightly raised area in the sun, Dad shouted, “What do you know? What a lucky day! Here are a few morels where I wouldn’t have expected them. You just never know where they’ll turn up.”

“You can have them, Dad. They don’t look so good to me,” I explained to him.

“Well, I will consider myself lucky to eat them fried in butter when we get home. But you have to try them sometime. They are a delicacy that people hunt for every spring,” said Dad.

Dad showed me the correct way to pick them, pinching them off a bit above the ground so they could grow back next year. We put them in our net bag so the spores could fall out as we walked.

“I hear a bluebird, Dad. You taught me that call last year,” I reminded him.

“Yes, you’re right. Listen! I hear another bird in the distance, a bird that likes the deep woods and has the most melodic song. It’s my favorite, the wood thrush,” Dad revealed.

I listened intently and, sure enough, I heard this flute-like call that was such a comforting sound. It made me feel like the woods was my home.

As we stepped forward, a garter snake slithered over my shoe. “Eek”, I shrieked.

“It won’t hurt you,” Dad reminded me. He is just looking for a worm to eat. You scared him more than he scared you.

“If you say so, Dad, but I’m glad he’s on his way,” I whispered.

And now we were to begin our search for signs of lady slippers my dad announced. “They’re rare around here,” Dad would always say. He wanted to find one but never did in our woods. But his walks with me in the spring made me love the woods forever.

Whenever springtime arrives, I look forward to a walk in the woods and the pleasures of the sights, smells and sounds it has to offer. I feel calm and peaceful there. And I remember Dad telling me to help keep the woods wild for other kids to enjoy, too.

And one day I’ll find that lady slipper!

Historical – City of Mackinaw engraving - 1850

I Want to Say

by Rosemary Gegare

For my father

Something about the painting tells me

I should have known you better,

known the old adage comes after,

not before the tree is felled,

and the rings counted one

by one to exact its measure.

Like the gardener seated pensive,

his arms crossed, his hat tipped

to one side—you were weary

of the hat you wore, keeping

for the strands of saving grace,

colors chosen by the painter.

When you penciled yourself into

the “Little Boy Blue” nursery rhyme,

I mistook the torrent, thinking

the disparity in the watercolor,

so ordered by the painter, trying

to make sense of you and me.

Afterglow

by Rosemary Gegare

Mother was a crack of light

like the Woodwick on the table.

A meld of modest resolve

her roots grown in utter regard.

She reared ten of us, and smote

despair—and in the afterglow

cursed the man who ran

with abandon, after the storm.

FICTION

The Hotel Bantam

by Adam Dompierre

“Watch your step now.” The genial middle-aged tour guide was dressed professionally in blue and white, and her voice carried through the length of the hallway, reaching all seven people behind her. She led the way up a staircase to her left, including the deceptively large first step she had just warned her charges about. One by one, the tour group followed behind her.

Roger was last in line, and he watched the others navigate the incline with varying levels of gracefulness. He surveyed the rest of the group. Among them were a pair of couples. The first he put in their 70s, both huddled deep inside their coats against the cold. Even that couldn’t hide their enthusiasm though, and they followed closely on the tour guide’s heels, peppering her with questions as they traversed from building to building and from room to room.