Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

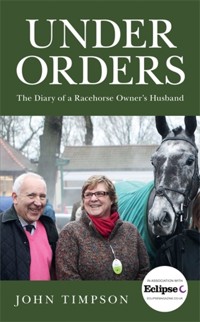

When John Timpson, chairman of the eponymous high street chain, bought his wife Alex a racehorse in 2002, a friend commented that it would be 'a marvellous way to lose money'. Soon they were immersed in a world of trainers' yards, Novice Hurdles and handicaps, and well on the way to proving the old adage that the best way to make a small fortune is to start with a larger one, and buy a few racehorses. As the number of horses increased and Alex became a well-loved figure on the racing scene, John kept a diary of their experiences on and off the track. This witty book describes how racing brought something extra into their marriage – from Mondays at Ludlow to the Cheltenham Festival. It documents the wins, near misses, disappointments and occasional tragedies that make up a racing career – not to mention the friends made, the knowledge gained and the sheer thrill of it all. Under Orders is a joyous and humorous portrait of horseracing in Britain and a tribute to the owners whose dedication and enthusiasm make the whole thing possible. Sales of the book will raise money for the Injured Jockeys Fund.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

UNDER ORDERS

The Diary of a Racehorse Owner’s Husband

JOHN TIMPSON

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

ECLIPSEMAGAZINE.CO.UK

Published in the UK in 2016

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services,

Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in the USA

by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada

by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300,

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

ISBN: 978-1-78578-145-2

Text copyright © 2016 John Timpson

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Agmena Pro by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK

by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

CONTENTS

Grateful thanks

An expensive hobby

A beginner’s guide to horseracing

Racing dictionary

2008–2009

2009–2010

2010–2011

2011–2012

2012–2013

Our geriatric gap year – 2013

2013–2014

2014–2015

2015–2016

Conclusions

Statistics

GRATEFUL THANKS

I would like to say a mammoth thank you to the four people who have made my involvement with racing such an unexpected pleasure.

If I hadn’t been married to Alex I probably never would have been near a racecourse. This book describes how I was given the opportunity to turn her big dream into reality and share her pleasure in planning and participating in life as a National Hunt owner. Alex loved people, and people-watching, and found plenty to see and enjoy during thirteen years as an owner. Sharing that experience introduced me to the rich pageantry of the racing world and provided the contents for this book.

My heartfelt thanks also go to Henry Daly, Paul Webber and Venetia Williams who patiently taught us all we know about racing. This book persistently points out the cost of being an owner, an investment that is seldom rewarded with prize money but Alex gained enormous pleasure from having a string of horses in training.

We might have lost money, but statistically our trainers have helped us perform better than most owners. As well as providing plenty of winners they also became close friends.

I hope they will forgive me for invading their world by talking about trainers from an owner’s perspective. I make it quite clear that horse ownership is likely to lose you money but I hope the reader will sense the pleasure that it brings and that I can tempt some new owners to join the sport.

This book is dedicated to Alex, who brought so much fun and adventure into my life, but she would have been the first to acknowledge how lucky we were to find the perfect three trainers to give us an above average amount of success and an awful lot of pleasure.

AN EXPENSIVE HOBBY

It’s amazing how many astute businessmen abandon common sense and invest in a football club. I would never fall for such a foolish trap. My football investment has been limited to three season tickets and the 1,000 Manchester City shares I gave Alex for Christmas in 1998. She liked the shares, but really wanted the racehorse she had coveted for twenty years.

In 1978 I bought her a greyhound called ‘Pepper Hill’. It did well, a first and a couple of seconds in six outings. To advertise shoe repairs, I changed its name to ‘While You Wait’, two weeks later it went lame. We had fun while it lasted but I always knew the dog was a poor substitute for the horse Alex really wanted.

For the next two decades horses never crossed Alex’s mind: she was too preoccupied with children – not just cooking meals and attending school plays, speech days and sports days for Victoria, James and Edward but also doing exactly the same for 90 foster children and our adopted sons Oliver and Henry. With so many distractions I was confident that the desire to own a racehorse had disappeared to the very back of her mind. But the more I got to know Alex the more she surprised me.

In 2001 Alex’s interest in racing was rekindled at Uttoxeter during a ‘personal experience package’ bought in a charity auction. She went behind the scenes, sat in the commentary box, spent time in the weighing room, observed a stewards’ enquiry and saw scantily dressed jockeys changing between races.

I weakened and promised Alex her racehorse. First we needed a trainer. Following a tip, Alex spoke to longtime friend and past racehorse owner Mike Coghlan to ask: ‘Can you find me a good-looking racehorse trainer within an hour’s drive of our home?’ Mike put the same question to a trainer he knew well, Paul Webber, who didn’t have to think for long. ‘There can be only one man,’ said Paul, ‘Henry Daly at Downton Stables near Ludlow.’ So the next day I rang Henry Daly and asked a silly question: ‘I want to buy a horse, can you help?’

Within a week, we visited Henry’s yard. The stables are in wonderful countryside, near to Ludlow’s prodigious choice of restaurants. Alex didn’t notice the scenery, her eyes were on Henry, whose charm has recruited plenty of women owners. Before we left, he had the job of finding our winner. ‘Must be a grey,’ insisted Alex. ‘Greys are more expensive,’ said Henry, as he handed over his schedule of training fees.

Henry went to Newmarket and bought a grey. It was expensive, at £17,500 a lot more than I’d expected. Transatlantic, successful on the Flat, was about to become our National Hunt star. I knew I was committed when Alex chose her racing colours. ‘City blue and white will look pretty on a grey.’

Three weeks later we returned to Ludlow. I expected Transatlantic would be put through his paces, chasing across the gallops and jumping a few fences, but he simply walked round the yard. Alex was delighted until she faced a difficult decision. To ensure jumping success, Transatlantic must be gelded, and I had to pay our first vets’ fee.

After two months’ schooling, we watched him on the gallops. ‘He is doing well,’ said Henry, ‘just a bit keen.’ I nodded knowingly. We were keen too, we desperately wanted to see him on a racecourse, but Henry was in no rush.

We waited three months for Transatlantic’s first race, Henry kept saying the going was too soft. We prayed for sun and at last he announced Transatlantic was running at Ludlow next Thursday.

The Racing Post quoted Transatlantic as 3/1 favourite. Seeing my excitement several colleagues at the office visited the bookies. At Ludlow, I raced to the Tote to place £20 each way.

In the parade ring Henry looked pretty pleased. ‘He’s a bit keen,’ he said to leading jockey Richard Johnson. ‘Keep him at the back, settle down and let him go five from home.’ Transatlantic ran sideways down to the start and the odds went out to 8/1.

As soon as the race started I understood what Henry meant by ‘a bit keen’. Transatlantic’s head pulled in every direction while Richard Johnson held him back. The crowd started giggling and within 2 furlongs Transatlantic was a laughing stock. With five fences left, he was shattered, finishing 72 lengths behind the winner. As I left the racecourse, an unhappy punter discarded his betting slip muttering, ‘bloody grey’.

His next race was little better, 7th out of nine at Worcester. At Huntingdon, Transatlantic wasn’t quite as keen and finished 5th.

His last race of the season, at Hereford, clashed with a family funeral. We watched in the bookies at Castle Cary. I placed £10 each way, and Alex revealed her ownership to our three fellow customers. He faded with three hurdles to go, and the room went quiet, a man with sideburns, swayed by our enthusiasm, had £40 on the nose.

Henry decided it was time for a summer break. Transatlantic went out to grass and my training fees halved.

At Henry’s Open Day, Alex proudly watched Transatlantic parade before a large crowd. ‘New here this year,’ said Henry. ‘Transatlantic performs well on the gallops but has a distinct dislike of racecourses.’ For the first time I began to wonder whether he had any chance of being a future champion.

His next appearance was at Leicester, a racecourse without charm or atmosphere. He was still pretty keen, but instead of fading on the second circuit, ran on strongly to finish 2nd, winning £378.00. Alex was ecstatic. I did a quick calculation.

‘Those winnings give you a 1 per cent return on my investment.’ ‘That’s good,’ she said.

Our attention turned to Bangor-on-Dee, where I sponsored the fifth race as a surprise for our second son, ‘The Edward Timpson 30th Birthday Hurdle’. To add to the occasion, we persuaded Henry Daly to enter Transatlantic, who started second favourite in the first race.

Bangor is our local course and the crowd included twelve members of my golf club. They all backed Transatlantic. He was keener than ever and faded with six fences left. A jaded jockey met us after the race. ‘Problem there,’ he said, with an Irish accent. ‘Veers right, can’t take left-handed courses.’ That eliminated half of Britain’s tracks and shattered Alex’s dream of Cheltenham and Aintree.

When Henry rang a fortnight later, it wasn’t good news. ‘Something happened in the loose box last weekend,’ he said. ‘It may be a bruise but it could be a tendon. I’ve called the vet.’ Three vets’ fees later, the news was no better. Transatlantic was confined to quarters and Henry declared the end to another season.

That night, I gave Alex some financial facts. ‘Transatlantic has only cost us £44,000, Manchester City pay Robbie Fowler that much in a week. Investing in football clubs is like pouring money down a drain, at least with horses you lose money at a somewhat slower rate.’ Alex wasn’t listening. ‘I spoke to Henry today,’ she said. ‘We are visiting the Doncaster Sales. One horse is great fun, but to really enjoy racing, you need at least five.’

It was foolish to think that Alex’s horseracing ambition would stop at the first fence, if I’d really thought it through, one horse was bound to lead to another. I was, however, lucky that the next step was somewhat cheaper. Following a casual conversation with long-time friend Mike Coghlan we took a quarter share in a syndicate by buying a leg of a horse called Pressgang, trained by Paul Webber at Cropredy near Banbury. But this smart move didn’t stop Alex taking me to the Doncaster Sales where Henry Daly successfully bid for Thievery. Instead of one horse we now had two-and-a-quarter.

Pressgang was a winner. Despite the difficulty of finding the right race in a hard winter, when several meetings were cancelled, we easily got a place in the Weatherbys Bumper at the Cheltenham Festival. Alex’s goal was a runner at The Festival and within three years of becoming an owner she was there – albeit only owning a leg, but at least she was 25 per cent there.

We had been to Cheltenham before – corporately entertained and fighting the crowds between every race. Life in the Owners’ and Trainers’ wasn’t any more comfortable but with a runner, and an enthusiastic mention in that day’s Racing Post, we felt pretty high up The Festival pecking order.

All four legs were well represented at lunch, we chatted in the bar, watched Pressgang being saddled up and posed in the parade ring. We watched the race in silence as Pressgang, always handy, put his nose in front as the field went up the hill towards the finish.

Despite the temptation to dream of a win I had an uncharacteristically pessimistic view of our prospects. All that changed when Pressgang was in the lead with 2 furlongs to go. Despite Pressgang producing an inexperienced wobble from side to side on the hill towards the finish, Paul Webber was so convinced we’d won he gave me an enormous hug. It was a premature celebration, we lost by a head.

In retrospect our taste of Cheltenham Festival prize money came too soon. We didn’t realise how rare it is to own a horse that is good enough to enter, never mind finding one that can stride proudly into the Winners’ enclosure.

Encouraged by our syndicate success Alex was happy for us to buy another leg – this time it was Presence of Mind trained by Emma Lavelle based between Andover and Newbury. We were the northern cousins of the syndicate and quickly found that ‘our’ horse never ran at a nearby racecourse. Bangor, Aintree and Haydock are a long way from Andover. Presence of Mind did us a favour by failing to make any progress through the handicaps and we decided our personality is more suited to sole ownership. A correct (but expensive) decision.

We quickly bought two more horses: Ordre de Bataille with Henry Daly (the French breeders wouldn’t let us change the name) and our first wholly owned horse with Paul Webber, which I was allowed to call Key Cutter.

Ordre de Bataille made history when he gave Alex her first win – a hurdle race at Warwick which we were awarded after the true winner was disqualified. The Racing Post reported ‘Killard Point, ridden by Joe Tizzard was demoted following a stewards’ enquiry for causing interference to Ordre de Bataille in a head to head struggle after the final flight.’ At the finish they were separated by a short head. ‘I feel sorry for trainer Caroline Bailey, who was denied her first winner,’ said winning trainer Henry Daly, ‘but it means a first winner for owner Alex Stimpson.’ Alex subsequently became much better known on the racing scene and most pundits now know how to spell her name.

Flushed with success it wasn’t long before we went beyond the suggested target of five horses in training with the addition of Timpo and Cobbler’s Queen. I hoped that we had now invested enough to make Alex’s new hobby really interesting. Some might think that by owning a number of horses we would benefit from economies of scale, but the simple rule is ‘The more horses you own the more you pay out’.

Racehorse ownership came at the perfect time for Alex. For 25 years foster caring had filled her life. It wasn’t just the 80 children who spent between two weeks and two years in our home; Alex kept a close eye on many who went back to mum or dad and became a long term family mentor in her role as foster granny.

In 2003 we decided it was time to retire from fostering. With a growing number of grandchildren of our own, a wish to spend more time on holiday and James, our eldest son, now running the family business, it seemed the right time to be a bit more selfish and give Alex her long held wish to be a racehorse owner.

I should have known that Alex wouldn’t stick to the plan. We continued fostering for another four years and looked after seven more children before Alex decided that we would continue for just a few more months to look after a family of three children. They stayed for over two years.

Alex has always been interested in children. She was trained as a nursery nurse and before we were married worked as a nanny for families in London and Cheshire. When our youngest child went to school Alex looked for something to do to fill her time. She loved people watching and got to know lots of other mums at the school gate but preferred inviting their children round for tea to going out clothes shopping or meeting the other mothers for lunch. She can remember the names of most of those children, proof that your memory retains the details that interest you most.

When looking to find a way to fill the time while our children were at school Alex saw an advert appealing for foster carers and found the interest that filled a big chunk of her life.

Alex finally gave up fostering after 31 years but still found a way to look after more children by becoming a Home Start volunteer.

I have no doubt that racing helped to take a bit of Alex’s attention away from her vastly extended family, but I wasn’t surprised to discover that she quickly started to show the same unselfish care and attention to the world of racing. The welfare of her horses, the stable lads, the jockeys, our trainers and, of course, their children is far more important than winning a race.

Alex always gave her trainers the freedom to make the major decisions, but they eventually realised that she had become very knowledgeable about racing and knew a lot about her horses. They became another part of her extended family.

Towards the end of 2007, Alex decided to alter our kitchen. She only wanted to move the Aga, but it got a bit out of hand and led to a redesign of half our house. To fill a large expanse of wall by our refectory table Alex commissioned a painting by horse artist Alex Charles Jones. The picture was of Cheltenham during The Festival, with Transatlantic, our first racehorse, at the centre of a group of runners waiting at the start. Transatlantic was a promising 2nd on a miserable Monday at Leicester, but he never went to Cheltenham for any meeting and certainly hasn’t appeared at The Festival. We were still waiting for his first win when I was sent to watch him run at Stratford. Alex couldn’t get a baby sitter for our foster children so I went to the course on my own, with strict instructions to give £20 to the stable lad and listen carefully to what our jockey, Richard Johnson, said after the race.

I did as I was told, handing the money over as Transatlantic was saddled up and even made careful note of the pre-race conversation in the paddock: ‘Settle him down in the middle of the field, keep him handy and hope we are in with a shout with 2 furlongs to go.’

From the start ‘Tranny’, as Alex affectionately called her horse, followed the plan. Richard Johnson settled him into the middle of the field and I felt the tingle of excitement that most owners experience whenever they watch one of their horses contesting a race. With half a mile to go I felt that tingle turn to disappointment as Tranny failed to get handy and lost touch with the leading pack. We finished 11th out of thirteen.

To complete my brief I rushed over to the area where the unplaced horses were unsaddled and hosed down while their jockeys explained why things hadn’t gone according to plan. ‘Nice horse,’ Richard told me, trying to soften the bad news, ‘but there simply isn’t enough pace there. Mind you,’ he continued, ‘if we look hard enough over the next two or three years we will eventually find a race he can win, but if I were you I wouldn’t bother.’ That was enough for me, Transatlantic had run his last race, he was retired and came to the fields behind our house in Cheshire where he was cared for by Jan who rents and runs the riding stables at the end of our garden.

Jan’s clients thought Transatlantic (now renamed ‘Tricky’) was very pretty but no one could ride him. ‘Too highly strung,’ they said. ‘A thoroughbred trained for racing – hardly the sort to take for a hack.’ Jan was the only person who could ride Tricky and once she built his confidence she started to teach him a few new tricks. One day Jan came down to our house carrying a rosette. Tricky had won a junior dressage class. We proudly pinned the rosette on a framed copy of a picture, taken of Transatlantic after his best run at Leicester, that was hanging in the kitchen next to the painting of his make believe appearance at Cheltenham.

This was the first of many rosettes. Every week Jan took Tricky to another level and one week she even won £6. After three years of training and vets’ fees I was at last seeing some income in return for my expenditure, but it didn’t last long. Tricky was getting so good at dressage, Jan said he needed a trainer, who, for a fairly modest fee, accelerated their progress. But the extra exercises took their toll and Tricky ‘got a leg’. I paid off the trainer and started paying the vet.

At first Tricky responded to treatment and there were even hints that if all went well he could have the talent to challenge for the Olympics. Unfortunately we never got the chance to commission a picture of Tricky in the London 2012 dressage arena. A repetition of the leg injury ended his career before he was able to catch the GB selectors’ eyes and just before his dressage prize money reached the £378 he had won while racing in Alex’s colours.

He now lives a life of leisure, eating our grass, in the fields behind our house, rent free. He hardly ever troubles the vet and has cost me a lot less since he stopped trying to win any prize money.

Cobbler’s Queen ran her first race in a big money, mares-only bumper at Sandown on 8 March 2008 and finished 7th.

‘A bit green,’ said Richard Johnson, as he returned to the paddock. ‘She shied away from the starter and travelled 1½ miles at the back of the field before she started to race. But coming 7th in a quality field shows some promise.’

The owners next to us in the paddock looked depressed. They expected their mare to win – it didn’t. ‘But,’ said their jockey, ‘it’s a nice horse and should do well over hurdles next season.’

Two weeks later Henry Daly telephoned to tell us Cobbler’s Queen was entered for the Friday of the Grand National meeting at Aintree, which, he added, is one of the five best days on the racing calendar. The race was at 5.30pm, giving me time to spend the morning at our office. Without my approval, son James introduced Dress-Down Friday so many colleagues turn up in jeans and a t-shirt. Being a rebel, I put on a pinstripe suit and a particularly loud shirt that Alex gave me for my birthday. It brought some cutting comments at our pensions meeting.

We got to Aintree for the second race. It was very busy. Forty-eight thousand racegoers were taking Friday off to have a party. It was Ladies’ Day, the sun was shining and the girls must have seen the weather forecast. They were scantily dressed, prepared for a heat wave.

On the way to the Owners’ and Trainers’ we passed groups of girls in wedding gear and others fit for a nightclub. Evening gowns, puff ball dresses, stilettos, garish colours, sequins and lots of orange sun tan. In the safety of the Owners’ and Trainers’, mixing with rather less bare flesh but plenty of silly hats, we claimed our free sandwich and our son Edward went to the bar. I gave him a £10 note, but Alex wanted champagne so I swapped it for £20. Edward returned with two glasses of champagne and a lager. I held my hand out for the change – there wasn’t any. ‘I had to put in another £1.50,’ said Edward.

The third race was the big one. Master Minded was odds-on favourite, but Edward backed Voy Por Ustedes. We watched the race with difficulty. Why do some people stand within two feet of the television screen, obscuring the view for the twenty decent folk who keep a sensible distance? The favourite faltered at the second from home and Edward won enough money to fund his betting for the rest of the day. I should have been pleased for him, but felt a feeling of jealous irritation as I tore up my betting slip.

For the next three races I went from paddock to Tote to grandstand and only once returned to the Tote to collect a very modest return for a horse that came 3rd. I didn’t see much of the horses but understood why Henry Daly thinks this is such an important day on the racing calendar. We were part of an amazing fashion parade and I was glad I was wearing my fancy shirt.

Alcohol gradually eliminated any inhibitions, but the sexes remained separated. Boys stuck together with their big ties and open-necked shirts and the girls spent all afternoon showing off to other girls – and they had plenty to show. With gravity-defying dresses and powerful bras putting plenty of orange flesh on view to reveal the results of cosmetic surgery – we even saw a few boobs popping up in the Owners’ and Trainers’ bar.

Henry Daly concentrated on the horses. He had a good day. Palarshan finished 5th over the Grand National fences and in the next race Alderburn came 3rd. Henry had a big smile as he put the saddle on Cobbler’s Queen, ‘5th, 3rd, what next?’

In the paddock I looked up at the big video screen and there we all were. Alex was centre stage talking to Henry and our jockey, Mark Bradburne. But our picture didn’t stay on screen for long, it quickly flicked to show more of the girls, this time tottering home – most didn’t stay for the last race.

Cobbler’s Queen was pretty keen and stopped suddenly on the way to the start, but Mark continued and was unceremoniously dumped on the ground. Reunited for the start they settled in the middle of the field and that’s where they stayed – finishing 13th. Mark came towards us and jumped off Cobbler’s Queen. ‘Bit green,’ he said, ‘but a lovely horse. She’ll be good over hurdles next season.’

Slightly disappointed we made our way back to the car. We will give Ladies’ Day another go next season.

Five years after we bought our first horse, Transatlantic, I got a call from Karen. Karen’s father, who had died suddenly a year earlier, was a long-time member of the snooker club that plays at my house. Karen was starting a website about racing, and asked me to write a short article through the eyes of an owner. I’ve written something every few weeks ever since for eclipsemagazine.co.uk. This book is based on those notes which chart the ups and downs of an owner’s phlegmatic husband who has managed to find plenty of pleasure among a catalogue of failures and joy from the occasional success.

Karen not only prompted me to keep more careful notes but also persuaded me to reveal a few financial facts. ‘I know you realise you are losing money but how much?’ she said.

It took some time to face up to reality so before I reveal the extent of our financial folly I think the casual racegoer should learn some of the basic facts before I turn them into figures.

My notes could provide helpful research for anyone with thoughts of following Alex and becoming an owner. If you have the courage to follow in her footsteps you are about to enter a new world where you will have a lot of fun mixed with a fair slice of disappointment. You will need a lot of luck and never know quite what is going to happen next, but I can almost 100 per cent guarantee that your investment in racing will lose you money.

A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO HORSERACING

A LOT TO LEARN

When I went with Alex to Downton Stables and asked Henry Daly to buy our first racehorse, I was totally naïve. I knew next to nothing about the world of racing. To help readers of this book avoid the same level of ignorance, I’m starting with some useful facts, discovered through experience, during the fourteen years I’ve given Alex’s hobby the financial encouragement it required. This knowhow probably cost me about £1 million, but I’m happy to hand it on for free. The facts that follow are unlikely to make you a profit, but they should help you understand my story and spot where I could have saved more money, and lost a little bit less.

FLAT OR NATIONAL HUNT

Some fixtures are on the Flat, at others the horses jump fences (National Hunt). There’s a big difference between the two – at least as big as the gap between rugby union and rugby league and probably as far apart as rugby and Association football. The meetings are usually held at different courses with different horses involving a completely different set of people. Different trainers, jockeys, owners and racegoers, but you see the same bookies.

I’m lucky that Alex only wanted to follow National Hunt racing. The leading Flat owners are multi-billionaire Sheikhs from Dubai while we only have to compete with multi-millionaires from Ireland. Flat horses have to be quick, speed that is nearly always inherited from their parents, so you will probably have to pay at least £300,000 for a horse with the credentials to run in The Derby with a late entry fee costing up to £60,000. Six-figure sums are also paid for jump horses but it is possible to pick up a future Grand National winner for £20,000.

You won’t find many National Hunt jockeys riding on the Flat because most of them are too tall and have enough trouble keeping their weight down to ten stone, the minimum weight a horse has to carry over the jumps. Flat jockeys need to be two stone lighter but you won’t persuade them to go over fences, which involve a far greater chance of falling off and finishing the race in an ambulance.

It’s not just the jockeys that look different, Flat horses are built for speed over a short distance (usually no more than a mile) while jump horses are made of sterner stuff, some with the stamina to go over 4 miles on muddy ground. A National Hunt horse usually doesn’t make its debut until it has reached four years and can still be competing at the age of thirteen. Flat horses start racing when they are two and may be retired to stud before they are four.

Flat races use starting stalls with the draw for position giving some runners a substantial advantage. National Hunt jockeys walk their horses gently towards a tape that is casually released by the starter. With a race of at least 4 miles the starting position doesn’t make much difference. A Flat race of 5 furlongs seems to be over in a blink of an eye while a jumping drama can go on for five minutes or more.

Although there are National Hunt meetings all year round the serious stuff happens in the winter (from November until just after the Grand National in April). Flat racing starts with the Lincoln Handicap at the end of March until the November Handicap, but to please the bookies Flat races take place on all-weather tracks nearly every day of the year.

A few horses, some jockeys and a lot of racegoers have their first experience at a Point-to-Point. This is jump racing for amateur riders over some farmers’ fields watched by a crowd wearing tweeds and Hunter wellies, eating smoked salmon sandwiches and drinking champagne by the boots of their Range Rovers.

These Point-to-Point followers will almost certainly take their tweeds to Cheltenham but if they have to go to Epsom, Chester and York (reluctantly accepting corporate entertainment) they will look as if they are guests at a fairly posh family wedding.

Some courses only do Jump racing, including Towcester, Uttoxeter, Bangor-on-Dee, Warwick, Wetherby and Wincanton, and it is Flat only at others, such as Redcar, Ripon, Windsor and Wolverhampton, but there are plenty of courses that do both, including Carlisle, Catterick, Leicester and Lingfield.

This book follows the fortunes of our string of National Hunt horses – I suspect it is just as easy to lose money on the Flat.

SIGNS OF A GOOD HORSE

If you go to the races you’ll find a lot of the crowd crammed into the bar, but some dedicated spectators spend time studying form by watching runners in the parade ring. Look out for the knowledgeable punters leaning on the rail making meaningful notes in their race card. You may wonder what they are looking for, why they pick one horse ahead of another and what’s behind their authoritative remarks: ‘you have to like the look of that grey’, or ‘he’s much more composed than last time out’ and ‘that mare’s built for chasing’.

There are some obvious warning signs to make you think twice about placing a bet. Keep clear if a horse is sweating before even seeing a hurdle or so keen the head is being jerked in all directions. Horses in the paddock should look calm and content. The experts on the rails will also look at bone structure, leg movement and body shape – ‘notice a strong line through the withers’ – but the first-time racegoer doesn’t need to be an expert to pick a winner.

It’s reassuring to discover that the diehards don’t always win, despite a detailed study of the Racing Post to check past form, present rating and preference for soft or good ground. Perhaps some of these seasoned spectators are being blinded by their own bravado.

By all means go to the paddock and see what you are investing your money in, but there are plenty of ways to choose a likely winner without knowing much about horses. Some punters forget about the horse and concentrate on the jockey, but even A.P. McCoy couldn’t win if he was riding a dobbin. Others go for the colour of the horse (Alex always backed greys) or the colour of the racing silks, although there is no evidence to suggest that when the jockey is wearing a green top and a red hat the horse will run faster than those wearing blue.

One of my friends backed a horse because he believed it winked at him while walking round the paddock; others have found success simply by selecting a horse with a nice name. If one of the runners is Victoria’s Secret and your daughter is called Victoria you’d be a fool not to have a couple of pounds each way even if the Racing Post says it hasn’t got a chance of getting in the first four.

The safest way to pick a winner isn’t to look at the horse but to look at the odds. At a general election the most reliable way to forecast the result isn’t to study the candidates or the opinion polls – the best information comes from the bookies. The same is true of racing, the horse with the shortest odds is the one most likely to win. You won’t make a fortune from an even money bet but at least you have a better chance of enjoying the smug satisfaction of going back to the bookie to pick up some winnings.

If you pick the wrong horse in the 2.45 at Folkestone the feeling of disappointment is soon forgotten, but your decision is far more serious when buying a racehorse at the Doncaster Sales. Instead of placing £10 each way you could be spending at least £20,000 with a lot more to follow when the bills start coming from your trainer and the vet.

This is a decision even the most experienced owner should never take on their own. I’ve always relied heavily on our trainer, who should know a lot more about horses and has a big interest in getting successful horses into the yard. If future events prove you have backed the wrong horse at least you’ve someone else to blame.

At the races, viewing horses in the parade ring is optional. You don’t have to look before you bet, but at bloodstock sales you are expected to look at the horse before bidding. Stable lads are only too willing to put their horse through its paces before the lot comes up for auction. While your trainer tries to come to an expert opinion your job is to watch the horse walk up and down while giving the occasional nod, smile or scowl to suggest that you know what you are looking for. Your trainer will be looking for a fluent and measured stride, a healthy coat, broad buttocks and a confident demeanour. After seeing six or seven horses, without analysing the size of their ears, the length of stride or gleam in their eye, I started to get a feel for which ones I fancied, then found I couldn’t afford them. The really good looking racehorses stand out from the crowd, that’s why the multi-millionaire owners push the prices over £100,000.

Most of the horses on offer have never seen a racecourse or even a saddle. There is nothing in the form book, all you have to go on is their appearance and the pedigree. The auction brochure lists past performances of the mare, and of the stallion, along with the good horses he has already produced. Beyond that you are bidding for an unknown quantity. The parentage should show whether you are buying a chaser or a hurdler, but until the horse starts running there is nothing to tell you whether it prefers left- or right-handed courses, heavy or good ground or would find it difficult to run more than 2 miles. All horses in the catalogue come with a clean bill of health from the vet so apart from noticing that every horse has long and worryingly fragile looking legs there is no indication of the extensive list of injuries that are likely to interrupt the horse’s racing career.

When the bidding starts I recommend delegating the job to your trainer, who should know when to enter the bidding and you will have told him when to stop. Don’t bid against yourself by catching the auctioneer’s eye or waving to a friend and if you have two trainers try to ensure they don’t bid against each other.

It’s quite exciting, being involved in the auction. It’s as tense as watching the horse run a race and unless you have the highest bid it doesn’t cost any money. Although many of the lots you fancy will go way beyond your price bracket, don’t worry about leaving empty-handed. Your trainer will make sure you will find something with potential to put in a horse box.

Don’t be fooled by the price, you are paying guineas (£1.05p each) not pounds. In addition, expect a 6 per cent commission, VAT, transport to your trainer’s yard and some vets’ fees. Once your horse has been delivered to its new home the clock starts ticking on the training fees at about £35 a day.

Don’t lie to your friends about the price, it is public knowledge; the details will be listed in the racing press the day after the auction and probably mentioned in the race card ‘Slippery Shoeman who cost 35,000 guineas as a three-year-old has his debut today’. After a disappointing run even if you don’t hear any comments from the crowd you know they will be thinking ‘who in their right mind has paid so much for a horse like that!’

You could keep the price a secret by dealing directly with a trainer, breeder or another owner but, like second-hand cars, you’ll never know whether you could have paid a lower price.

Whatever price you pay, my advice is to forget the figure as soon as possible, and hope you have a horse that is worth the daily training fees that you are now committed to pay.

PICKING YOUR COLOURS AND CHOOSING NAMES

It might be very difficult to find a future champion chaser but it’s easy to pick the racing colours that jockeys will wear whenever they ride your horses. There are eighteen different shades available which can be combined in thousands of ways to produce your personal, unique design. It can all be done on the internet, using a website so simple even I can work it. Play around with your favourite colours on different patterns for tunic, sleeves and hat until you find a combination that the computer says isn’t already being used by another owner.

Inevitably you will have to pay a modest registration fee. Your trainer will be happy to arrange for the silks to be made (‘worth getting three done, just in case’) and add the cost to your next monthly bill. That’s it, you now have the colours that will appear on the race card and in the Racing Post but no picture in the paper will look as good as seeing the silks worn for the first time when your jockey tries to find you in the parade ring.

Picking the name of your horse should be even more fun. You can give your imagination a real treat by listing a load of likely names before deciding on your favourite, but be prepared for possible disappointment. There are a number of rules which mean that some names can’t be chosen.

Obviously you can’t pick a name that is already being used or has been in use during the last twenty years, a rule that extends for ever to famous names like Red Rum and Shergar. You have eighteen characters to play with, which means that the total of all the letters and spaces can’t add up to more than eighteen. To get a long name, some owners don’t bother with any spaces and end up with names like ‘Shutthedoorquietly’, ‘Whataloadofrubbish’ or ‘Shesinthekitchen’, which I think are silly.

Again there is a neat website that lets you check whether your favourite name is available. Don’t assume that the obvious names have already been taken. A quick recent check revealed that the following can still be used: ‘Racing Certainty’, ‘Easy Peasy’, ‘Each Way Bet’ and ‘Don’t Tell Alex’ but I do wonder whether some others like ‘Four Lengths Ahead’ or ‘Back Marker’ would be ruled out for causing potential nightmares to a commentator. You certainly won’t sneak through a name designed to produce an embarrassing broadcast. ‘Yoovarted’, ‘Efinhel’, ‘Four Fuxake’ and ‘For Gas Mick’ are all unlikely to get past the judge.

It is safer to stick to family names (‘Ask John’ and ‘Popular Pete’ are still available) or something connected to your pets, hobbies, house name or favourite holiday destination. Your choice of name is unlikely to make the horse jump better or run any faster and the name will be totally ignored by the stable lads who’ll invent their own nickname, but every time your horse is mentioned there is the satisfaction of knowing that you dreamt up the idea.

There are other restrictions. If the horse has already been given a name by a previous owner or breeder you can only change it with their permission (French breeders can be particularly reluctant to cooperate). If the horse has run in a race under one name you can’t change it to another but at least that will spare you the £150 fee due whenever you register a new name. The £650 plus VAT you pay to set yourself up with silks and give the horse a name is small change compared with the cost of getting it fit to run in a race.

OTHER OWNERS

Owners come in all shapes and sizes, most are ordinary people, like you, who pick racing as their extravagant hobby. Your fellow owners could include Liz Hurley, Sir Alex Ferguson and Ronnie Wood, but most aren’t celebrities and have never been seen in Hello magazine. There are some really serious owners like John P. McManus, Trevor Hemmings and Graham Wylie who have so many horses they often have several running at the same meeting and more than one in the same race (same colours, different hat). Your best-known fellow owner will be The Queen, but only a few of her horses go jumping so you are unlikely to see her at Bangor-on-Dee, Towcester or even Aintree and even if she did turn up she won’t, like you, have to present her Horseracing Privilege Card after queueing at the Owners’ and Trainers’ entrance.

Don’t be fooled, some people in the queue aren’t owners or trainers. As an owner you can bring four, six or sometimes even eight guests, who may arrive on their own and pick up their badges at the gate. Others in the queue may be part of a syndicate – up to half the horses on a race card could be part owned by two friends or ten mates from a pub or golf club. If you divide the costs between ten people you all get into the parade ring but only lose one-tenth of the money.

Syndicates sound like the ideal way to get the same thrill at a fraction of the cost, but it may not work out like that. Much depends on your fellow investors, if they’re a crowd of good mates your visits to a racecourse will, win or lose, provide plenty of enjoyment. You can get an extra bit of fun for your investment by dreaming up an unusual name for the partnership. Look at some of the great names in the Racing Post and wonder why syndicates are called The Yes No Wait Sorries, Old Boys’ Network, Good Bad and Ugly and the Impulse Club.

Some syndicates don’t last the test of time. Poorly performing horses can cause discontent among the members but disharmony is more likely to be caused by a person than a horse. Each syndicate needs a leader, someone who collects the money, briefs the trainer, pays the bills and very occasionally declares a dividend. The syndicate starts to crumble when some members realise that they are putting up the cash for the leader to enjoy all the best parts of being an owner. It’s the person who talks to the trainer that gets the most pleasure out of planning the season’s campaign and picking the right race (at an adjacent course on a convenient date). Sure, everyone in the syndicate gets to celebrate if the horse wins, but the organiser will expect a fair slice of the credit.

People that own a leg (25 per cent) are close to the action and the trainer probably knows their names. Members of one of the commercial racing clubs, where for about £25 a week they get a modest share in what they hope isn’t a modest horse, haven’t bought much more involvement than the punter who puts on £50 to win. But punters can decide on the day. If you join a syndicate you are stuck with the same horse wherever, whenever and if ever it runs.

Although the big owners’ clubs claim that you are in proud possession of part of a horse, the system is close to fantasy football – you place your bet at the beginning of the season, and there is no chance of changing your bet from month to month.

But psychologically, subscribing to an owners’ club is definitely one step up from being a plain punter, who imagines he owns the horse for one race only – in an owners’ club a tiny little bit of the winning horse really does belong to you.