Unfinished Business E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

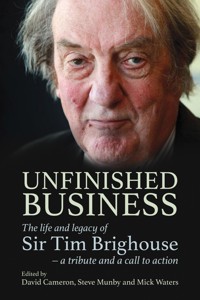

Edited by David Cameron, Steve Munby and Mick Waters, Unfinished Business is both a tribute to Sir Tim Brighouse and a call to action based on Tim's approaches, commitment and ideas. The first part of the book celebrates Tim's life and achievements. This includes contributions from his son Harry and longstanding colleagues and friends such as Bob Moon, David Woods and Jo n Coles. These accounts provide a rounded picture of Tim and, in a sense, make the case for listening to him and commemorating him in action rather than simply celebrating his memory. This part also includes contributions from David Blunkett and Estelle Morris that underline Tim's national status. The second part of the book is forward-looking with contributions from close friends, career colleague, policy makers, politicians and the people that Tim thought made the most difference: teachers in schools. Contributors explore what we need to do now in order to continue Tim's work in their particular area of expertise. Contributors include: Mel AinscowDavid CarterSam FreedmanLucy KirkhamSteve MunbyAmjad AliLena CarterMichael FullanBridget KnightMary MyattFiona Aubrey-SmithJulia CleverdonTony GallagherEmma KnightJames NottinghamKenneth BakerJon ColesChristine GilbertJim KnightAlison PeacockDavid BellKevan CollinsIan GilbertPriya LakhaniHywel RobertsMelissa BennEllie CostelloTy GoldingBill LucasLiz RobinsonLouise BlackburnLeora CruddasMark GrundyJames MannionAnthony SeldonDavid BlunkettBen DavisAndy HargreavesRachel McFarlaneRachel SylvesterAdam BoxerColin DiamondJohn HattieLaura McInerneyMick WalkerHarry BrighouseGraham DonaldsonLouise HaywardNiall McWilliamsMick WatersAnna BushEd DorrellJaved KhanFiona MillarDavid WoodsDavid CameronMaggie FarrarDebra KiddBob Moon Rosemary Campbell StevensEvelyn FordeChris KilkennyEstelle Morris Suitable for all educators and readers interested in the future of education.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 392

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to Tim’s family, friends and colleagues and to teachers everywhere who will take Tim’s legacy to future generations of children.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who contributed to the book so willingly, who met, or at least got close to meeting, some very tight deadlines and graciously accepted comments and edits. We also thank all of those who could have and would have contributed. We know that many of them will be making other contributions to keeping Tim’s legacy alive and continuing his work. We would also like to thank the team at Crown House Publishing for making this book a reality.

Royalties and a share of profits from sales of this book will be donated to Tim’s favourite charities and causes.ii

Contents

List of contributors

Professor Mel Ainscow, CBE FRSA

Mel Ainscow is emeritus professor, University of Manchester, professor of education, University of Glasgow and adjunct professor, Queensland University of Technology. He is internationally recognised as an authority on the promotion of inclusion and equity in education. Mel worked with Tim Brighouse on City Challenge in London and Greater Manchester.

Amjad Ali

Amjad Ali is a teacher, trainer, TEDx speaker, author and senior leader. He has a background in challenging, diverse schools and young offender prisons, and co-founded the BAMEed Network. Amjad has delivered continuing professional development at events alongside Sir Tim and was fortunate to have been informally mentored and supported by him.

Dr Fiona Aubrey-Smith

Fiona Aubrey-Smith is a consultant researcher and school system leader who is known for her infectious enthusiasm, pedagogy-first approach and championing of agency for young people. Fiona worked closely with Tim and Mick and an advisory team to curate the formation of Open School.

Kenneth Baker, Baron Baker of Dorking, CH PC

Kenneth Baker is a former MP and cabinet minister. As education secretary, he introduced the national curriculum, city technology colleges and grant-maintained schools. He is the chair of Baker Dearing Educational Trust which promotes university technical colleges. Over the course of the last 40 years, he had several healthy debates with Tim about vital educational matters.

Sir David Bell, KCB DL

David Bell is vice-chancellor and chief executive of the University of Sunderland. He has been a local authority director of education – paralleling Tim’s time in Birmingham, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools and permanent secretary at the Department for Education where he engaged positively with Tim.x

Melissa Benn

Melissa Benn is a writer and campaigner. Her books on education include SchoolWars:TheBattleforBritain’sEducation(2012) and LifeLessons:TheCaseforaNationalEducationService(2018). A former chair of Comprehensive Future and co-founder of the Private Education Policy Forum, she was a great admirer of Tim’s.

Louise Blackburn

First and foremost, Louise Blackburn is an advocate for disadvantaged learners. Having worked in education for over 20 years, she now supports schools to deliver equitable approaches through Challenging Education, which works with leaders to tackle inequalities through Raising the Attainment of Disadvantaged Youngsters (RADY). It is this passion for equity that brought Louise into contact with Tim.

David Blunkett, Baron Blunkett, PC

David Blunkett drew upon the experience, expertise and wisdom of Tim Brighouse when he was education and employment secretary between 1997 and 2001. Together putting ideas into practice and inspiring others led to a continuing friendship which David values to this day. What they started with Excellence in Cities led to Tim’s success in leading the London Challenge.

Adam Boxer

Adam Boxer is a science teacher, teacher trainer and education director of Carousel Learning. Although he never met Tim, Adam corresponded with him on a number of occasions, often on points they disagreed upon!

Professor Harry Brighouse

Harry Brighouse is Mildred Fish Harnack Professor of Philosophy of Education and Carol Dickson Bascom Professor of Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Tim Brighouse was his father.

Anna Bush

Anna Bush has worked in education for 20 years and currently works for United Learning. A role on the London Challenge meant working closely with Tim Brighouse and getting behind the efforts of the capital’s most challenging schools. Anna is known for her passion and commitment – or, in Tim’s words, ‘Anna is easy to work with and gets things done.’xi

David Cameron

David Cameron has had a long and varied career in education. He met Tim at a conference years ago. Tim said he would tell people to book him instead of Tim. He did. They became colleagues and friends. David sees that as one of the greatest honours of his life and hopes this book repays that to some small extent.

Rosemary Campbell-Stephens, MBE

Rosemary Campbell-Stephens is an international speaker, author and consultant on leadership and decolonising system change. She first met Tim Brighouse when he was Birmingham’s chief education officer. Over the years, they have shared various platforms on numerous occasions. Most notably, their paths crossed during the London Challenge work from 2003 to 2011.

Sir David Carter, KNZM

David Carter has been in education since 1983 as a teacher and leader of schools and trusts. David knew Tim for more than 20 years as a mentor and someone who inspired his own personal leadership journey, and believes he talked common sense in a world where at times this seemed to be lacking.

Lena Carter

Lena Carter started her career in Cambridgeshire in 1992. She is currently a shared head teacher of two rural Scottish primary schools. In 2017, she had the good fortune to spend a weekend with Tim and educators from across the UK, exploring how our four countries can learn from one another.

Dame Julia Cleverdon, DCVO CBE

In 1985, while Julia Cleverdon was working as director of education for the Industrial Society, she led a four-day leadership course with Tim for 50 deputy heads at St John’s College, Oxford. Their 40-year collaboration continued through Business in the Community, his tremendous support for Teach First and the Fair Education Alliance Summit in 2023.

Sir Jon Coles

Jon Coles is the chief executive of United Learning. From 2002 to 2005, he was director of the London Challenge, where he worked closely with Tim.xii

Sir Kevan Collins

Tim’s wisdom guided Kevan Collins’ work as a school leader, local authority adviser and in his national work. He will always be grateful for the time Tim gave him and his unmatched ability to remind us that grace, humour and human connections are the lifeblood of our work.

Ellie Costello

Ellie Costello is executive director at Square Peg and a long-time fangirl of Sir Tim. Square Peg is a community interest company working to ensure that any young people who are marginalised or unable to attend, access or remain in education are at the heart of policy, development and improvement, giving us a brighter future for all.

Leora Cruddas, CBE

Leora Cruddas is the founding chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts – the national organisation and sector body for school trusts in England. She had a feisty relationship with Tim founded on mutual respect. She is visiting professor at UCL Institute of Education. Leora was awarded a CBE in the New Year’s Honours in 2022.

Ben Davis

Ben Davis is the head teacher at St Ambrose Barlow RC High School in Salford. Prior to this he worked as a head in Scotland, where he first encountered Tim through David Cameron, an association that continued after his move to England in 2015.

Professor Colin Diamond, CBE

Colin Diamond first met Tim in 2000 when visiting Birmingham. He recalls his abundant energy and chaotic office! Fast forward to 2015, and Colin took over as director of education in Birmingham, where everyone talked admiringly of the ‘Tim years’ and his legacy, and Colin felt that he was walking on the shoulders of a giant.

Professor Graham Donaldson, CB

Graham Donaldson and Tim have shared platforms on many occasions. Tim’s unassuming manner and gift for connecting with an audience were unfailingly impressive, and Graham’s admiration for him has continued to grow. They shared a passion for education and for supporting unfashionable football teams. Tim will be a huge loss as an inspiration and a friend. His wise counsel will endure.xiii

Ed Dorrell

Ed Dorrell is a partner at Public First, where he leads on schools policy, strategic communications and qualitative research. He has authored several influential education policy papers. For 12 years before taking up this role, he was a senior journalist at the TES, and worked closely with Tim.

Maggie Farrar, CBE

Maggie Farrar first worked with Tim when she set up the University of the First Age in Birmingham. Since then he has provided support and inspiration as a mentor and friend through her time as a director at the National College for School Leadership and now as a leadership coach.

Evelyn Forde, MBE

Evelyn Forde was head teacher of Copthall School in Mill Hill, North London from 2016 to 2023, during which time she led the school to achieve significant improved outcomes and worked with staff to secure a range of accolades for the school. In 2022, Tim and Evelyn contributed to the Commission on Teacher Retention.

Sam Freedman

Sam Freedman has worked in education for 20 years, including as an adviser at the Department for Education. He is now a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Government. He never had a chance to work with Tim, but wishes he had.

Professor Michael Fullan, OC

Although they were very much the same age, Michael Fullan always thought of Tim Brighouse as a mysterious elder senior statesman. He was a practitioner, policymaker, professor. He never said much to Michael personally, but they had similar ideas. They borrowed ideas frequently from each other and Michael came to realise that they were quietly sympatico – a feeling that he deeply cherishes.

Professor Tony Gallagher

Tony Gallagher is professor emeritus at Queen’s University Belfast and was honoured to read the citation for Tim’s honorary doctorate. Tony and Tim were appointed as academic advisers to the Review Body on Post-Primary Education in Northern Ireland (1999–2000), and Tim chaired the governing body of a school collaboration project led by Tony (2010–2013).xiv

Dame Christine Gilbert, DBE

As teacher, head teacher, director of education and Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector at Ofsted, Christine was inspired by Tim for over 30 years and is proud to have worked with him. An Honorary Fellow at UCL, Christine is chair of the Education Endowment Foundation and of Camden Learning, a school company.

Ian Gilbert

Ian Gilbert is an educational author and speaker and the founder of Independent Thinking. Celebrating its 30th birthday in 2024, this organisation was in its infancy when Ian first saw Tim Brighouse speak at a head teacher conference in Oxford. It was an event that Ian still talks about to this day.

Ty Golding

Ty Golding was only able to hear Tim speak at a conference once, yet he was extremely grateful for a brief and memorable conversation at that event. It was from there that Ty began to read more about Tim’s work, and his ideas began to influence Ty’s thinking, leadership and, most recently, his role in the development of Curriculum for Wales.

Sir Mark Grundy

Mark Grundy has been associated with Shireland Collegiate Academy for over 25 years, initially as principal and more recently as CEO of the trust. Over the years, Tim was a frequent visitor, looking at the use of technology to support school improvement and the innovations in curriculum delivery across the trust’s primary and secondary schools.

Professor Andy Hargreaves

Andy Hargreaves is an adviser to education ministers in Scotland and Canada. He co-founded and is president of the ARC Education Collaboratory. Andy worked at the University of Oxford when it partnered closely with Tim Brighouse’s Oxfordshire local education authority in the 1980s, and has presented with Tim on many occasions.xv

Professor John Hattie, ONZM

John Hattie is emeritus laureate professor at the University of Melbourne and previously chair of the board of the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. Like Tim, he has worked within and outside government, been a critic and developer, and Tim and John have shared many conundrums about how to make a system work more effectively for educators and students.

Professor Louise Hayward

Louise Hayward has worked in practice, policy and research in Scotland and internationally to transform assessment experiences for all learners. Tim was a role model for her: a powerful educationalist who lived by the values he espoused and understood the potential for assessment to promote social justice.

Dr Javed Khan, OBE

Javed Khan is a former CEO of Barnardo’s and a director of education. He first met Tim as a teacher in Birmingham, and was appointed to Tim’s team in 2000 as assistant director where he saw Tim’s magical impact at close quarters – and credits his success since then to what he learned.

Dr Debra Kidd

Debra Kidd is leader of learning and teaching at the British School of Brussels and an author and teacher trainer. As co-founder of Northern Rocks, she was grateful to benefit from the wise contributions of Tim Brighouse and proud to contribute to his and Mick Waters’ book, AboutOurSchools.

Chris Kilkenny

Chris Kilkenny is a campaigner and activist striving to end the impact of poverty, when he is not busy sorting out his own life. He is currently working to get into university to become a teacher and make a difference for children from difficult circumstances, like his own. Tim Brighouse encouraged his ambitions.xvi

Lucy Kirkham

Lucy Kirkham teaches geography at Bassaleg School, Newport, South Wales. Lucy met Tim when she hosted a discussion into young people’s views on climate change. Lucy and her students went on to organise a climate education conference in June 2023 where Tim’s speech was a highlight of the day.

Bridget Knight

Bridget Knight is a teaching head, CEO of Values-based Education and editor of OntheSubjectofValues…andtheValueofSubjects(2022). Tim Brighouse has been a standard bearer through her whole career. With him, we knew that teaching could be about educating the whole person.

Jim Knight, Baron Knight of Weymouth

Jim Knight chairs the boards of E-Act Multi-Academy Trust, the Council of British International Schools, Century-Tech and Educate Ventures Research. He worked with Tim as schools minister before serving as employment minister in the cabinet and joining the Lords in 2010. His continued work in education included regular discussions with Tim.

Emma Knights, OBE

Emma Knights was chief executive of the National Governance Association from 2010 to 2024, growing the organisation and the understanding of good governance. She had the privilege of representing the voices of school governors and academy trustees across England. It was through this national role that Emma knew Tim Brighouse.

Priya Lakhani, OBE

Priya Lakhani has deeply admired Tim’s work for many years while building Century Tech. She was privileged to be on the National Teaching Awards board that honoured Tim with its inaugural Award for Lifetime Achievement, recognising his remarkable contribution to education.

Professor Bill Lucas

Bill Lucas is professor of learning at the University of Winchester, co-founder of Rethinking Assessment and an acclaimed education reformer. At the start of his career, Tim seconded Bill to develop the Oxford Certificate of Achievement, and Bill taught at Peers School where Tim’s son, Harry, was a student.xvii

Rachel Macfarlane

Rachel Macfarlane writes and leads training on various aspects of educational equity. As a programme leader for the London Leadership Strategy, Rachel heard Tim speak on many occasions. He kindly addressed leaders at various conferences that she organised from 2005 to 2023. On each occasion, he sprinkled gold dust and lifted and challenged colleagues.

Dr James Mannion

James Mannion is the director of Rethinking Education, a teacher training organisation specialising in self-regulated learning, implementation and improvement science. James is also the host of the Rethinking Education podcast, where he first met Tim, and the host of the Rethinking Education conference network, which hosted Tim as a keynote speaker in 2022.

Laura McInerney

Laura McInerney is the CEO of Teacher Tapp, a daily survey of over 10,000 teachers. As a former journalist for SchoolsWeekand the Guardian, Laura had the pleasure of interviewing Tim Brighouse on several occasions and chaired a set of events alongside him at the Education Festival in 2023.

Niall McWilliams

Niall was formally the head teacher of the Oxford Academy, a school well known to Tim. Niall first met Tim when he arrived in Oxford to teach in the early 1990s. He continuously sought his advice throughout his numerous headships and leadership roles, including the managing director role that Niall held at Oxford United.

Fiona Millar

Fiona Millar is a writer and journalist specialising in education policy. She is also a school governor and campaigner for fairer school admissions. She first met Tim in 2003 and frequently spoke alongside him and interviewed him. They were also fellow members of the New Visions Group.

Professor Bob Moon, CBE FAcSS

Bob Moon began his teaching career in the Inner London Education Authority. He was head teacher of two secondary schools before becoming professor of education at the Open University in 1988. He has led many national and international teacher development programmes and was a member of Tim Brighouse’s London Challenge advisory team.xviii

Estelle Morris, Baroness Morris of Yardley, PC

Estelle Morris is a former secretary of state for education and was a Birmingham Labour MP during Tim’s time in the city. Prior to being elected to Parliament she was a teacher in an inner-city secondary school. She is now a member of the House of Lords and chairs the Birmingham Education Partnership.

Professor Steve Munby, CBE

Steve Munby has held various educational leadership roles including chief executive of the National College for School Leadership in England. He regards Tim as having had a hugely positive impact on his leadership. Tim was his mentor for more than 20 years.

Mary Myatt

Mary Myatt is an education adviser, writer and speaker. She trained as an RE teacher and is a former local authority adviser and inspector. She engages with pupils, teachers and leaders about learning, leadership and the curriculum. Her work has been informed by the wisdom, insights and humanity of Sir Tim Brighouse.

James Nottingham

James Nottingham is a teacher, consultant and author of 12 books. He leads demonstration lessons and creates commissioned videos for schools. A highlight of his career has been the many pinch-me-now moments as a second keynote speaker to Sir Tim’s headline presentations at education conferences across the UK.

Dame Alison Peacock, DBE DL FRSA

Dame Alison Peacock is chief executive of the Chartered College of Teaching. Her career spans secondary, primary and early years education. She is a lifelong teacher committed to the inclusive values of ‘learning without limits’. Alison is grateful that Sir Tim Brighouse was a great supporter of the Chartered College and thoroughly embraced the philosophy of reducing practices that label children.xix

Hywel Roberts

Hywel Roberts is a teacher, writer, bassist and brewer. His books include Oops!HelpingChildrenLearnAccidentally(2012), UnchartedTerritories(with Debra Kidd) (2018) and Botheredness(2022). Hywel worked alongside Sir Tim at conferences where he would be found nodding his head a lot. He hasn’t had enough of experts.

Liz Robinson

Liz Robinson is a school and system leader who has worked with underserved communities across London. Liz’s work focuses on challenging leaders to ‘think big’ about the purpose of school and has worked to radically reshape practices, based on a human-centred belief in the capacity of every child. Tim was a mentor and friend.

Sir Anthony Seldon, FRSA FRHistS FKC

Anthony Seldon was head of Brighton College and then Wellington College and first came across Tim in both institutions. They shared a fascination with education in its broadest sense, and what gives meaning and purpose to life. They also shared an interest in politics. Anthony has written the inside books on every prime minister from Margaret Thatcher to Liz Truss.

Rachel Sylvester

Rachel Sylvester is a journalist at TheTimesand chair of the Times Education Commission. Tim gave evidence to the Commission.

Dr Mick Walker

Mick Walker is a former executive director of education at the Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Leeds. Mick first met Tim Brighouse in 2006 when he was an adviser to the Expert Group on Assessment of which Tim was a member.

Mick Waters

Mick Waters was a colleague and friend of Tim for 25 years. Mick worked as a head teacher and in initial teacher education before joining Tim as chief adviser in Birmingham. He later became chief education officer in Manchester and director of curriculum at the Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency. Mick and Tim collaborated on AboutOurSchools(2022), which looked at policy change in English schooling since 1976.xx

David Woods, CBE

After an early career in teaching, teacher training and as a local education authority adviser, David Woods worked with Tim as chief education adviser in Birmingham until moving to the Department for Education. The partnership resumed when Tim was appointed as the commissioner for London schools and David became the lead adviser for the London Challenge.

Introduction

David Cameron

David Cameron has had a long and varied career in education. He met Tim at a conference years ago. Tim said he would tell people to book him instead of Tim. He did. They became colleagues and friends. David sees that as one of the greatest honours of his life and hopes this book repays that to some small extent.

This is a book filled with admiration, gratitude, love, respect and a host of other emotions all evoked by, and dedicated to, Tim Brighouse. We suspect Tim might have hated the attention. At the very least, he would have been very uncomfortable with all the emotion. We think he would have been much happier with the fact that it is full of ideas, forward-looking and determined to finish the work to which he devoted his life.

We wanted a book that commemorated Tim, and those who have contributed to it have done that well. He is captured in the round, with all his eccentricity, passion, enthusiasm, kindness and remarkable range of qualities and skills. His achievements are celebrated by others, but Tim was never likely to celebrate them himself. Despite all that he did, he never lived in the past, nor used his laurels for siestas.

He was always more likely to start a conversation with a new idea, a fresh plan or what we came to think of as ‘one of his ploys’. They often began with the relatively harmless, ‘I’ve been thinking …’ He never stopped ‘bloody thinking’, as he might have said, but he was brilliant at turning thoughts into action and action into achievement.

He had only recently finished AboutOurSchoolswith Mick Waters (2022). It is an epic which makes Tolstoy look like a short story specialist and Finnegan’sWakeresemble a graphic novel, without the graphics. He was already thinking about the next book.2

That is why this book is not just a tribute; it is a call to action. He wanted to do more to make education more humane, more fair and more effective. He wanted us to be more creative, to think more widely and more deeply and, above all, to help young people create a better future.

He often quoted George Bernard Shaw:

This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; the being a force of Nature instead of a feverish selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy. (Shaw, 1903: Epistle dedicatory)

I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the whole community, and as long as I live it is my privilege to do for it whatsoever I can.

I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I live. I rejoice in life for its own sake. Life is no ‘brief candle’ for me. It is a sort of splendid torch, which I have got hold of for the moment; and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations. (Shaw quoted in Henderson, 1911: 512)

This book asks you to pick up the torch.

We are grateful to all who have contributed to the book and deeply apologetic to all those who could have and didn’t get the opportunity. We are proud of the range of issues that are covered and of the diversity of the authors.

We hope that we have done him justice.

References

Brighouse, T. and Waters, M. (2022). About Our Schools: Improving on Previous Best. Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

Henderson, A. (1911). George Bernard Shaw: His Life and Works. A Critical Biography. Cincinnati, OH: Stewart & Kidd.

Shaw, G. B. (1903). Man and Superman: A Comedy and a Philosophy. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3328/3328-h/3328-h.htm.

Part I

A tribute4

Chapter 1

Finding the Holy Grail

Harry Brighouse

Harry Brighouse is Mildred Fish Harnack Professor of Philosophy of Education and Carol Dickson Bascom Professor of Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Tim Brighouse was his father.

When Tim died, the obituaries – as well as the outpouring on social media – emphasised two things. He was idealistic, in the sense that he was driven by an infectious vision of a better world and better education. And he related well to people, especially to teachers but also to children, who wanted to tell their stories to him and were inspired by the ideas he shared.

Those were essential parts of him. But you cannot achieve what he did with mere ideas and good relationships. You need also to be canny: to keep a close eye on opportunities and be able to take them.

Tim attributed his entire career success to a single canny decision. He loved university and enjoyed studying history, but didn’t devote himself entirely to the academic side, and so, when he finished his exams, he faced a viva which he knew would determine whether he would come out with a second-class or a third-class degree. He was confident that they would either viva him about the paper in which he had done best or the one in which he had done worst. His strategy was simple: focus entirely on preparing for a viva on the worst paper, and hope that if they ask about the best, his pre-existing expertise would suffice. They did indeed focus on the worst paper: he passed with flying colours and came out with a second. He confidently believed that a third would not have been good enough to get him his first job as a head of department at a girls’ grammar school in Buxton, which, in turn, was the essential springboard for other opportunities.

6After he started work in Oxfordshire, he became aware of a central government scheme supporting sabbaticals for teachers from his friend Barry Taylor (CEO in Somerset). A teacher could spend one year in professional development (take a university course, visit schools in another country, research pedagogy, write a novel), and the local education authority (LEA) would continue to pay their salary, while central government paid for the salary of a replacement teacher. LEAs had discretion over whom and what projects to approve. Suddenly, a lot of teachers in Oxfordshire (including novelist Philip Pullman) were taking sabbaticals, which was good both for morale and for enhancing the workforce: sabbatical-takers would return refreshed, loyal and often with new knowledge and skills. The same thing happened in Somerset and … nowhere else, because Tim and Barry kept their knowledge of the scheme to themselves. Of course, something like that cannot last; after a few years, other LEAs cottoned on and the government ended the scheme.

Tim was a fierce opponent of corporal punishment. Becoming the CEO in a Conservative-led local authority, he realised that it was pointless having an argument about whether it was okay to beat children, and that unilaterally ending it was beyond his remit. As he put it, ‘In a time of cuts, if I’d gone to the politicians and asked them for money for canes they’d ask me how many I wanted, and did I want the luxury versions.’ But when, in the mid-1980s, councillors began panicking that it might be impossible to comply with the then inevitable law against corporal punishment in schools, he assured them that they needed to do precisely nothing because he knew that none of the schools practised it.

He had initiated an annual survey on how often schools caned pupils. When the results were in, he gave each school the full list, showing the numbers of canings at each school, but with the names of all other schools redacted. The head at the top of the list was shocked to see that his school administered 25% of all the canings in the LEA, but Tim said something to the effect of, ‘It’s okay, that’s the way you like to do things at your school; I often hear the swish as I drive by’ [I realise he might have made that bit up, although many readers will know it is believable]. The following year canings were down substantially, even at that school, which was still at the top of the list, now accounting for 33% of all canings. Again, he was reassuring. Within two years, the league table was empty – there were no canings.

7In political philosophy, we distinguish between ideal theory and non-ideal theory. Crudely, ideal theory is about what a just society would be like; non-ideal theory takes those values and asks how they tell us to act in our unjust society, which we might be able to improve but cannot expect to make just by our actions. You cannot do non-ideal theory without ideals; but you also cannot do it without a clear vision of where you are and without acknowledging the unwelcome constraints you face. Tim was principled, yes, but also pragmatic and, in the best sense of the word, opportunistic.

This explains why he was willing to work closely with academies and academy trusts. He thought the academy programme and its predecessors were a serious policy mistake, not because he saw them as a neoliberal plot (I never heard him utter the word ‘neoliberal’), but because he believed that central government lacked the capacity to understand schools well enough to both support and regulate them. But once academies were a political reality, of course, there was no point in withholding resources from them: his view was that we should be doing everything we can to improve the quality of state schools, regardless of the form of governance.

I will finish with two non-professional stories: a success and a failure. The success: my godfather, John Walker, told this story at Tim’s funeral. Both families purchased a small, almost derelict (and very cheap), holiday cottage in mid-Wales in the 1970s. Tim was brilliant at many things, none of which involved DIY. So, John took on the many tasks of fixing up the place. Tim, meanwhile, got to know the local people, reducing the risk that the cottage would be burned down by nationalists. And, of course, he was brilliant at that, not only because of his egalitarian manner and genuine interest in other people, but because he was happy to give useful advice on educational matters for their children. Even the fiercely nationalistic Welsh language speaker in the nearest house was cordial. The cottage survived.

The failure, and it is less than disastrous: Tim loved Monty Python and was often compared with John Cleese (of whom he did an excellent impression). In 1977, he took me (14) and my sister (10) to see Monty Python and the Holy Grail at the Maidenhead Odeon, asking for ‘two adults and one child’. On being told that children weren’t allowed to see the film (incredible, really), he instantly said, ‘In that case, I’d like three adults please.’ I didn’t see Holy Grail until my own daughter turned 14, and I am not sure Tim ever did.8

Chapter 2

A talisman for the teaching profession

Bob Moon

Bob Moon began his teaching career in the Inner London Education Authority. He was head teacher of two secondary schools before becoming professor of education at the Open University in 1988. He has led many national and international teacher development programmes and was a member of Tim Brighouse’s London Challenge advisory team.

Tim and I first met in the early 1970s. He was the education officer in Buckinghamshire with responsibility for planning schools in the new city of Milton Keynes. I was one of a small group of teachers appointed to open the city’s first new comprehensive secondary school, Stantonbury Campus.

We went on to become good friends with a shared interest in county cricket, lower league football and more egalitarian versions of golf. And, of course, we debated educational issues, going on to write and occasionally speak together. We also had overlapping membership of some of the progressive pressure groups that sought to influence government. When we met up, Tim always had a new idea to share. A few days before he died, he rang me from his hospital bed. ‘Bloody boring in here,’ he said. We talked about the operations he was about to undergo, the signing of a new Australian spinner by Lancashire and then he said, ‘But, look, the reason I rang was to try out on you a devilishly fiendish plan I’ve thought up to finally deal with Ofsted!’

How did Tim come to be such a towering figure in the educational world? Why was he such a talisman for the teaching profession?

10Early experiences were important. Tim was unhappy in the first grammar school he attended, but the family then moved and Tim, with his brothers, transferred to Lowestoft Grammar School (now Ormiston Denes Academy, still in the Grade 2-listed school building Tim knew). It was a transformative experience. ‘The teachers were just more human,’ he once said to me, ‘and the atmosphere was different. I looked forward to going to school.’

Tim did well at school, went to Oxford and taught successfully for a few years, but he was then tempted by the offer of a post as an educational administrator in Monmouthshire. He had found his metier. ‘An LEA officer might sound a bit boring, but I discovered, even in junior positions, that I could make things happen, do things for schools,’ he told me. In that period, local education authorities (LEAs) were the equivalent of a local civil service, negotiating with the government as equals. Tim revered this world. He would frequently quote from the writings and work of chief officers like Alec Clegg and Henry Morris. During his time in Buckinghamshire, he became a protégé of Roy Harding, then one of the most influential chief education officers. Tim and Peter Newsam, the former Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) education officer, maintained a correspondence throughout their lives.

Tim was embracing the world of LEAs, and in his early jobs he was learning his trade. Later in his life, I heard people say that Tim was not a details person. Not true. His time in Monmouthshire, Buckinghamshire, the Association of County Councils and the ILEA allowed him to come to terms with the intricacies of financial planning, sites and buildings, school admissions and all the minutiae of running an education system. His abilities became well known, and he was soon the youngest education officer to serve on the influential expenditure steering group for education services, coordinating policy between government and the LEAs.

Tim’s first major leadership role in education was as chief education officer in Oxfordshire, a county with a progressive approach to primary education and with a fully comprehensive secondary school system. He was young to the role, in his late 30s, but he soon began to establish a national reputation as an education reformer. I was a secondary head teacher in Oxford (Peers School) through most of Tim’s time with the authority. Looking back, I think it was another period of apprenticeship for him, this time in leadership.

11Tim had become a hugely inspiring person with whom to work. He was bubbling with ideas, and Oxfordshire was his first opportunity to put these into practice. I would point to three as of particular significance. First, he felt schools should be more accountable, but he believed this should come from internal school self-evaluation. Second, he thought the way young people were judged in school should go beyond marks and grades, so he developed a new portfolio model (this time working in cooperation with a group of other LEAs). Third, he believed the structure of the school day was too inflexible and needed to be adjusted to allow for the provision of activities that did not feature in the traditional curriculum. These were all initiatives with a strong basis in the sort of values that Tim sought to foster.

Tim had a unique leadership style, one that it would be difficult to copy but one that had attributes from which anyone could learn. He had a natural patience, courtesy and kindness, and he was a good listener. He was passionate about schools becoming fairer and more welcoming (friendly) places for all children, and I have seen him almost personally wounded if he came across examples to the contrary. Tim was wary of prescription. He would have aims, but he felt that the way these could be achieved required deliberation and debate. I had a second period of working directly with Tim as one of the small advisory team implementing the London Challenge. The aim was clear, a rapid improvement in the performance of all London secondary schools, but advisers were given discretion as to how they worked with schools to achieve this.

In Oxfordshire, Tim had the limited support systems of the time, given the size of the authority. He would tirelessly tour the county giving talks and speeches extolling the rationale behind reform proposals. Later, in Birmingham and then in London, he had much more extensive support systems. Tim loved working in the wider team context. In Birmingham, where he faced political challenges and an initially hostile Ofsted inspection, he needed the emotional support that a good team gives. In London, he worked with a high-flying civil service team led by Jon Coles as well as an advisory group drawn from across the country. This gave him the space to do what he was so good at, winning the hearts and minds of the more than five hundred London secondary head teachers and the leaders of the 33 London education authorities.

12Tim never stopped working. Tens of thousands of teachers have heard him speak and many more have heard about him. He was a wonderful raconteur whether from a stage or amongst a group of family or friends. He had a superb memory for people, places and events. He had a restless, even incorrigible, intellectual energy that made him so revered in the world of education.

Debating with Tim was intellectually challenging, but it was also great fun. I recollect, just after the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing with him the idea of establishing an Open School. I had worked at the Open University for over 20 years, and it was an institution Tim greatly admired. We wrote an article for the Guardian (Brighouse and Moon, 2020), and I will always remember Tim’s delight at the positive feedback we received. Tim then gave a major place to the Open School concept in the book he wrote with Mick Waters, About Our Schools (Brighouse and Waters, 2022). Discussions about the Open School are ongoing. I do hope something could come of this. It would provide yet another marker for Tim’s extraordinary impact on the world of education.

References

Brighouse, T. and Moon, B. (2020). Like the Open University, We Now Need an Open School for the Whole Country. The Guardian (12 May). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/may/12/like-the-open-university-we-now-need-an-open-school-for-the-whole-country.

Brighouse, T. and Waters, M. (2022). About Our Schools: Improving on Previous Best. Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

Chapter 3

Inspirational, creative and innovative leadership: a tale of two cities

David Woods

After an early career in teaching, teacher training and as a local education authority adviser, David Woods worked with Tim as chief education adviser in Birmingham until moving to the Department for Education. The partnership resumed when Tim was appointed as the commissioner for London schools and David became the lead adviser for the London Challenge.

When Tim became chief education officer in Birmingham in 1993 and London’s school commissioner in 2003, many schools and educational communities were underperforming with generally low morale and ambition. There was a significant need for radical reform to get these cities to achieve excellence. Tim readily embraced these challenges. His approach was to get to know the schools, build relationships and seek partnerships to establish shared vision, values and beliefs to underpin improved education achievement. He astutely built leadership teams and capacity from the outset in both cities. He wanted people who would be energy creators, enthusiastic and always positive, using critical thinking, creativity and imagination – matching his own – to stimulate and spark others.

He shared his clear educational principles with everyone, and from these came a set of core purposes to secure success. The most crucial was to achieve a substantial increase in aspiration, ambition, expectations and outcomes. In both cities, his style involved visiting many schools and education partnerships, debating and communicating core principles and 14practice. Remarkably quickly, he won the trust and respect of various education communities.