Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

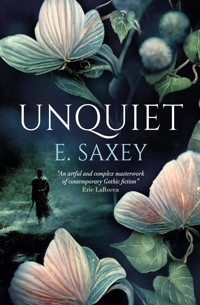

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

An intrepid young woman journeys across Victorian London and beyond in search of the truth behind the presumed death, and reappearance one icy evening, of her brother-in-law, in this gripping and mysterious gothic horror. Perfect for fans of The Haunting of Hill House and readers of Sarah Waters. London 1893. Judith lives a solitary life, save for the maid who haunts the family home in which she resides. Mourning the death of her brother-in-law, Sam, who drowned in an accident a year earlier, she distracts herself with art classes, books and strange rituals, whilst the rest of her family travel the world. One icy evening, conducting a ritual in her garden she discovers Sam, alive. He has no memory of the past year, and remembers little of the accident that appeared to take his life. Desperate to keep his reappearance a secret until she can discover the truth about what happened to him, Judith journeys outside of the West London Jewish community she calls home, to the scene of Sam's accident. But there are secrets waiting there for Judith, things that have been dormant for so long, and if she is to uncover all of them, she may have to admit to truths that she has been keeping from herself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Acknowledgements

About the Author

‘Unquiet deceptively presents itself like a frozen lake: The further one treads across E. Saxey’s haunting, delicate text, the closer to cracking the ice one gets. I fell through this gorgeously gothic novel and still haven’t come up for air.’

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN, AUTHOR OFGHOST EATERS

‘A wonderful gothic novel rife with mystery and unease; perfect for fans of Shirley Jackson.’

A.C. WISE, AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR OFWENDY, DARLINGANDHOOKED

‘Told with beguiling lyricism and compelling intensity, E. Saxey’s novel Unquiet is an artful and complex masterwork of contemporary Gothic fiction that will leave readers unsettled and clamoring for more written by such an exciting and unique voice in horror.’

ERIC LAROCCA, AUTHOR OFTHINGS HAVE GOTTEN WORSE SINCE WE LAST SPOKE AND OTHER MISFORTUNES

‘An exquisite gothic piece. Wrap yourself up and try and decide whether it’s warm like bedsheets or cold like a shroud.’

KIERON GILLEN, HUGO-NOMINATED AUTHOR OFTHE WICKED + THE DIVINE, DIEANDONCE & FUTURE

‘A brooding psychological gothic mystery, steeped in the darkest realms of folklore. Literally dripping with grief, desire, and guilt.’

ESSIE FOX, BESTSELLING AUTHOR OFTHE SONAMBULIST

‘Unquiet is a sly, enigmatic incantation of a book, full of mysteries and half-truths. E. Saxey creates something unique, both Gothic and quietly folk-horror-inflected, in their tale of grief, loss, unquiet spirits and outsiders.’

ALLY WILKES, BRAM STOKER AWARD®-NOMINATED AUTHOR OFALL THE WHITE SPACES

‘Beautifully written, dark, subtle and curious, Unquiet is one to savour and savour again. I loved it.’

A.J. ELWOOD, AUTHOR OFTHE COTTINGLEY CUCKOOANDTHE OTHER LIVES OF MISS EMILY WHITE

‘An engrossing, delicately atmospheric mystery.’

KIT WHITFIELD, AUTHOR OFBENIGHTEDANDIN THE HEART OF HIDDEN THINGS

‘With its deft prose, vivid characters and compelling plot, Unquiet really got under my skin. Tense, haunting and evocative, this is a gothic tale that won’t let you rest until you’ve unearthed every last one of its secrets.’

LOUISE CAREY, CO-AUTHOR OFTHE STEEL SERAGLIO

‘Dreamlike happenings, unexplained footsteps, and muddy trails: suffused with dread, and very elegantly written, Unquiet is a Gothic mystery to become mired in.’

ALIYA WHITELEY, AUTHOR OFTHE BEAUTYANDSKYWARD INN

‘Disquieting, atmospheric – a novel that will keep you on edge throughout.’

MARIE O’REGAN, AUTHOR OF BEST-SELLING NOVELCELESTE, EDITOR OFTWICE CURSEDANDTHE OTHER SIDE OF NEVER

‘I loved this glimpse into Judith’s interior world of loneliness and secrets. The ghostly scenery and mesmeric prose make this one of my favourite books of the year so far.’

VERITY M. HOLLOWAY, AUTHOR OFTHE OTHERS OF EDENWELL

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Unquiet

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364469

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364476

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© E. Saxey 2023

E. Saxey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Amy Levy and her luminous writing.

TUESDAY

I needed my charms to ward off madness. Scrabbling around in the cold scullery, I hauled out every drawer in the dresser to find myself a jam jar, a candle stub, a wineglass. I’d gathered them before but the maid had tidied them away. It was vital to bring them back together, and to open a new bottle of wine.

I had been alone in the house for almost four months. I didn’t regret ridding myself of my family. But it was odd to live alone, unseen and unheard, and easy to feel untethered. Impossible to recreate the family routines which had dropped away – Friday night dinner, brushing my sister’s hair, trips to take tea at Whiteleys. Instead, I had made routines of my own: rising at eight, art class at nine. I had invented rituals. Between them, I kept myself steady.

So tonight, I poured myself a glass of red wine. I intended to carry it down the long, narrow garden. Our home wasn’t large, having only six bedchambers, but Father had chosen it for its luxurious touches. It was the end house of a smart modern terrace, had fine rooms on the ground floor for visitors, and pillars at the front in an envious echo of nearby Kensington Palace Gardens. At the foot of the garden lay an ornamental lake. When I reached the lake, I’d spill some wine into the water, and drink the rest.

Lighting the candle wick, I dropped it into the jam jar, singeing my fingers. I was suddenly conscious that Mama would see this as a parody, in bad taste. Tonight was the first evening of Hanukkah; as I’d walked home, around sunset, I’d seen the candles in my neighbours’ windows. But I didn’t feel able to light our own, now Mama and my sister weren’t here.

As I carried the jar over to the kitchen door, the flame jumped up (a neighbour has gossip) and sparked (you will receive a letter soon). Outside the night was dark and bitingly cold. The moonlit silver treetops thrashed in the wind, and I loved it, because inside the house, so little moved if I didn’t move it. The maid, Lucy, could have helped, but she made it worse. She passed me in the hall without meeting my eyes, and everything I disturbed she put back in its place, so that it appeared nobody lived in my house at all.

The gravel path didn’t crunch under my feet. Had I become weightless? No, the gravel had frozen in place. This year, December had been unusually harsh.

After a minute of walking, the path gave out into lawn. My feet crushed prints into the frozen grass. I grasped my wine and my candle. I wouldn’t be sent away for a rest cure, like the classmate of mine with bad nerves.

In our childhood, my sister, Ruth, and I had performed all kinds of elaborate ceremonies in this garden. It was large enough to get lost in, or at least evade observation. I made a fine witch, with my unruly hair and my bony face. I’d cast spells, and blight every tree. Ruth, with her orderly ringlets, had played the princess. What did princesses do? Were they imprisoned in branches? Did they scry in the lake for true love? If only Ruth were here to remind me.

It was foolish to wish for Ruth because I let myself miss her. That pang multiplied, and I missed Mama, too. And – most painful, and most pointless – I missed Sam. His restless footsteps in our hall at the foot of the big staircase, his voice calling us to join him. I was hollow because he wasn’t here.

Panic rattled me. I was a candle flame, wick snipped, flickering away into the night sky.

Walk the path, I told myself. Reach the lake. Drink the wine. Go back to your room and bury yourself in your bed.

But there was an uncanny glow to the garden ahead of me, a whiteness beyond the dark trees. I pushed branches aside to reach it.

The lake had been transformed: where dark water should have rippled, there was flat pale ice. It was fantastical. Pure white at the edges, where the lake met its border of marble kerb stones. Grey towards the centre, where the ice thinned. Dark scrapes crossed the surface – from birds, trying to land on it?

How would I draw the ice? Layers of pale pastels, scraped through to dark paper? I could imagine my oily fingertips, a blunt blade.

It put me in mind of magical changes in ballads where boulders melt or a gate opens in a hill. Your love turns in your arms into red-hot metal, or a stranger. When had the lake last frozen? I recalled Mama snapping a warning as I ran towards it, in her mother tongue of Yiddish, then explaining in English that I’d drown if I set foot on it. I must have been very young.

A movement, on the far side of the white lake, and a rustling in the bushes. Probably a fox, wanting to drink and startled by the frost. I moved closer to the edge, with my wine and candle, and waited for it to emerge.

It wasn’t a fox. It was Sam.

He stood just twenty feet from me. The moon was bright. The absolute familiarity of him stamped itself on my eyes.

He waved, then he beckoned. I couldn’t move, so he walked towards me, one foot onto the white ice, and then another. Walking with complete confidence, not looking down, he trusted the ice to be thick enough to bear him.

Or, no – he hadn’t trusted anything. He’d mistaken the lake for a solid surface. His foot slipped and he paused, looking down in puzzlement.

I shouted a warning.

He dropped straight down in a barrage of cracking. A fountain of moon-white water shot up from where he’d stood.

Then there was nothing left but a foaming dark hole, and jostling plates of broken ice.

I ran round the edge of the lake, as close as I could get to the hole where Sam had vanished. I threw myself down at the pool’s edge, and kicked my toes into the earth to anchor myself. Stretching half my body onto the ice, I reached my arm out even further.

‘Sam!’

Water pulsed out of the hole, dark green, and sucked back, and there was no sign of him.

I screamed for help, but was anyone in earshot? Lucy would be cloistered in her attic bedroom. The cold would sink Sam and the ice would trap him. He was drowned. No refusing it, no haggling.

Sam’s head broke the surface. He made a great wheezing moan, dragging breath into his lungs. His arms punched out, and sliced through air and water. White foam flew everywhere around him. But his crashing was frantic, failing. He was going to sink again.

I yelled his name, stretching so far that the muscles under my arm burned.

Sam heaved himself forwards. He raised a dripping arm and reached out his hand to me.

I grabbed him. He didn’t feel human. His skin was slimy and his hand slipped from my grasp. I seized the sleeve of his jacket instead. I found purchase, and I felt his icy fingers clamp around my wrist.

I tensed my agonised body and dragged him in, hearing the ice crack with every pull.

He let go, abruptly. Released, I tumbled onto the grass. Sam didn’t fall back, though. He grabbed at clumps of reeds to haul himself up onto the marble kerb stones and out of the water.

On all fours on the grass, he started retching. I crawled until I was near him, but what should I do? Beat on his back? He drove the heel of one hand into his own chest, gave a horrible grating cough and then spat. His barking shaking head, his black slicked hair like fur, made him wolf-like in the moonlight.

Finally he lifted his face up to me, almost unrecognisable. I knew I must be just as smeared with filth, as open-mouthed and disgusting. One stain on his forehead looked more like blood than mud. Ruth would have reached out to it, tended it. I recoiled.

Sam’s hand, strong and cold, closed around my shoulder. When he pulled, I braced myself again, but he wasn’t trying to drag me closer. He was using me as a prop, swinging awkwardly round into a sitting position. When he managed to sit, he still kept hold of me.

For a long while we only breathed, both of us in ragged rasps. My lungs felt like I’d inhaled hot ashes. My arm, and my whole side where I’d thrown myself onto the ground, throbbed in pain.

But the disbelief was sharper. It couldn’t be him. It couldn’t be.

‘Sam?’

He met my eyes. ‘Judith!’

His voice was weak but it was warm. It was him.

He was back.

* * *

We hobbled up to the house together. Sam hung off me, a dead weight, his arm a vice around my shoulders. Trails of icy lake water poured from him, running down my scalp and sliding under my collar. My shoes had come off. It was so hard to trudge onwards when the gravel stabbed the soles of my feet.

As we reached the house I steered us off the main path.

‘Where are we going?’ he asked.

‘To the conservatory.’

I yanked open the glass-panelled door and shoved him through it. The big room was chilly, but dry and out of the wind.

Sam slumped onto a wrought-iron bench. Water streamed off him and pooled on the tiled floor.

‘Judith?’

‘Yes?’

‘Good.’ His tone was relieved, even though he’d asked nothing and I’d given him no answer. He covered his face with his hands, smearing the stain on his forehead, the ooze from the broken skin. It needed to be cleaned off, but everything I could reach was covered in dirt. ‘This is a mess,’ he murmured. He started to shiver, so hard that the bench jittered.

I sat down on a wicker chair and studied him. The light was dim, but he was certainly Sam. His familiarity was reassuring, now, rather than shocking. But it wasn’t a joyful sight, yet. I was too afraid: what if he was injured, frostbitten, waterlogged? What if he died, and this time it was my fault?

‘You need clothes. Dry clothes, that is.’ I didn’t know where I’d find them, but it gave me a task to perform, and a reason to run away.

* * *

I peeled off my stockings in the hallway, although they clung like weeds. My legs were yellow and green with old bruises – I had developed a habit of falling – and I would have fresh marks in the morning. I pattered on clammy feet down to the kitchen. Lucy wasn’t there. I’d been right: she’d retreated up to her attic for the night, thank goodness. In a cupboard I discovered old blankets, only fit for horses. I made a stack of them so high that I had to wedge it between my hands and my chin to carry it.

Back in the conservatory, I dropped the blankets beside Sam and left the room again.

He needed to be close to a fire. I was shuddering, and I’d not even been drenched, as Sam had. Our library would heat up the quickest. The large fireplace had been one reason Ruth and I had laid claim to the room, after Father had died. Entering it now, preparing it for Sam, I was conscious of how eccentric we had made the room look. We’d decorated the sober bookcases with fronds of pine, glossy holly and the heads of teasels, stencilled the walls, and hung up embroideries. And since I’d rid myself of my family, I’d been spending all my time here, covering the desk with paintbrushes and rags.

Which meant that in the big grate, under the coals, yesterday’s embers would still be glowing. I screwed up paper, stacked coals and blew life into the pyramid. My wing-backed chair was already next to the fire. I dragged another, Ruth’s favourite, to face it. Ruth’s chair was draped with patchwork quilts that she had made, and I flung them off to keep Sam from dripping on them.

I moved back through the hall, and called through the conservatory door to Sam: ‘Are you ready? May I come in?’ I meant ‘are you covered up’, but that was an indecent question. Opening the door, I stood by it, waiting. ‘I’ve lit a fire in the library.’

He lurched towards me. He’d wrapped the blankets round himself, and scrubbed his hair with one of them. Now he resembled a scruffy robed patriarch.

Halting at the threshold, he raised an eyebrow. He was still dabbed with slime, and my reluctance – my revulsion – was probably obvious from my screwed-up mouth. So I held out my arm, and said: ‘Please do come in.’

Together we entered the house proper, and slowly crossed the hall. Sam had been our most frequent visitor, energetically pacing here under Father’s paintings as he waited for my sister to descend the stairs. Now it took him an age to limp over to the library door.

Inside, Sam moved into the fire’s radius and folded himself into Ruth’s chair. The firelight showed up his mud-matted hair, but his hands – emerging from the blankets – were cleaner, and his long fingers exactly as they’d always been. He had dark eyes in a long face, and long hands to match.

Good news, then. I finally started to feel joy at his return, kindling in me as the fire grew. Good news? The best news! When he went missing, it had wrecked Ruth, my sister, Sam’s betrothed. And it had struck Sam’s brother, Toby, as well, and even taken the heart out of Mama. Two small families twisted up with loss like crumpled paper. That could be undone, ironed out. And all the horrible things that had happened since, the hundred lesser sadnesses. Sam’s return would reverse all those, as well.

My sister had been so sad, for a year, that her own body had been a burden to her. Now she’d be freed. In a sense, she would never even have been bereaved.

I brought all this to mind, but I couldn’t yet feel it. My heart was as numb as my hands. I needed to heat myself, then I’d feel glad.

‘Good Lord. That was frightening,’ Sam said. He didn’t sound frightened. His voice was faint, but he sounded elated, as though we’d cheated and won. His eyes shone.

‘Are you hurt at all?’ I asked.

‘Did I scare you?’

Had he heard me? ‘Sam, have you injured yourself?’

‘No, but did I? Frighten you?’

He smiled. His smile conjured one back from me. It was so typical of him to be frivolous. ‘No!’

‘I don’t believe you. I’m still terrified! Scared myself rotten.’

I needed him to show less levity. ‘Are you hurt, though? What do you need? A doctor?’

‘No. I’m utterly freezing, but there’s nothing else amiss.’

‘Do you need…’ I looked around for more coverings for him. There were only the patchwork quilts, which Ruth had pieced together out of fur and brocade, like offcuts from a coronation robe. They were more decorative than practical. ‘What do you need?’

‘A hot drink would be a marvellous thing. It might thaw my blood.’ Sam stamped his bare feet on the hearthrug. ‘Ow! That was a terrible idea.’

I hid my own bare feet under the wet hem of my dress.

‘Thank you so much for all this, Judith,’ Sam added. ‘I suppose there’s no way to clean me up a bit, before the others see me?’

I was suddenly aware of every empty room in our house. ‘They’re not at home now.’ I didn’t say more, because liars give themselves away with long excuses.

‘Where?’

‘Let me fetch you that drink.’

‘You’re very kind. Above and beyond, really, Judith.’

* * *

I didn’t need Lucy to heat a pan of milk, down in the kitchen. Ruth and I preferred the rest of the house to look old-fashioned, but the kitchen was very modern. Any London cook would have refused to work over a Tudor roasting spit.

The surface of the milk was smooth. Staring at it, I stated the simplest facts to myself: Sam’s back. He’s here, he’s in my house with me.

Bubbles began to pop up in the milk.

I had expected to feel joy again but it had turned to numbness. The white circle of milk in the pan reminded me of the ice on the lake. The bubbles clustered.

Sam had asked where my family were.

The milk erupted, and the overspill scalded on the stove-top.

I cleaned up the mess, blotting stinking milk off the flagstone floor with a cloth. I poured all the liquid I could rescue into two cups, over lumpy cocoa powder, and jabbed them with a spoon until they turned rich and soothing.

When I came back into the library, the chair was empty where Sam had been. Then I saw him, seated opposite, in my chair.

‘This one was out of the draught. You don’t mind?’ I handed over the hot cup and Sam bent his fingers gratefully around it. ‘And the door?’

The library door should stay open while we were in here together, for the sake of propriety, but the draught was keen so I pulled it closed. The chair Sam had abandoned was probably cold and damp, so I crouched by the grate and pretended the fire needed tending.

‘So you can’t be all by yourself, all night? Can you?’ He was teasing me.

‘Of course I can’t.’ What could I tell him?

‘Of course, your sister wouldn’t be so careless as to leave you alone.’ She’d been very careless. She’d left me alone for months. ‘So…?’

‘As soon as you’re not drowning, you want to talk to the others.’ If he could tease me, I could respond in kind. But I knew I sounded quite brittle. I picked up the bellows and puffed up the fire.

The heat finally began to lick at our faces. Leaning away, I watched Sam gradually coming to life in the warmth.

‘Really, when are they back? It’s late, isn’t it?’ He craned his head up to look at the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘They can’t have left you here. It can’t just be you.’

‘Can’t it?’

‘No, but is it?’

Lying and confessing were both unthinkable, and my voice failed me.

‘Come on, Judith, do tell me. Why won’t you? Are they where they oughtn’t to be? Somewhere improper? Out watching a French revue? Ooh la la…’

I had to stop him talking, and that unlocked my own tongue. ‘My family are in Italy.’

His smiling mouth dropped further open.

‘They’re most likely in Venice, right now,’ I explained.

‘In Italy? No! How?’

Why was he so incredulous? It was more plausible that my family were travelling in Italy than that Sam was here, in our library. My family had booked tickets, caught a boat and boarded trains. Goodness knows what route Sam had taken to get here.

‘Mama and –’ I made myself say her name. ‘Mama and Ruth are in Italy. With your brother, Toby.’

He nodded at me slowly, as if to say touché, trying to understand the joke I was making.

‘I should see Ruth,’ he said. ‘I should certainly talk to her. That’s it, isn’t it? I should set things straight with her.’ He was sheepish, as though he’d forgotten a dinner appointment. He watched for my reaction.

‘Well, you can’t talk to her tonight.’ It was true, but it sounded spiteful. I was too exhausted to command my voice.

‘Because she’s…’

‘In Italy.’

‘It’s important, though. I have to make amends for something, don’t I? Patch something up. Come on, Judith, don’t be cross with me. I’ll do the decent thing, whatever it is.’ He was bargaining with me. He had all his usual confidence and the start of a sly smile: just between you and me, he was hinting, give me a clue.

He leaned over, clutching his blankets, to fumble with the coal tongs and add more pieces from the scuttle to the fire.

‘She’s in Venice! I’m not lying to you. She’s gone, she isn’t here.’

That stopped his smile. ‘Who’s staying here with you?’

He was asking after my companion, my chaperone. I couldn’t be drawn into that conversation. ‘There’s nobody here.’

Panic welled up in my battered body. He knew what I’d done. He’d end my brief spell of freedom. His eyes wandered over me, as if seeking evidence. He must be staring at the mud on my clothes. I brushed at the worst of it, but it smeared across my skirts.

‘Is that truly your dress?’ he asked. ‘Not some costume?’

An impertinent question, doubly so given his sodden blanket robes. ‘Of course.’

‘What about those velvet frocks you and Ruth always wear – have you both turned respectable?’

Ruth and I shared a passion for aesthetic dress. We’d paraded around in loose velvet gowns, looking mediaeval and (according to many men in the street) ridiculous. Tragedy had forced us both back into ordinary dresses, with stiff panels and boning that limited your movements, and made it necessary to put on an air of caution. I resented my new wardrobe, although Ruth said the clothes fortified her. I wouldn’t let Sam mock me for these clothes.

‘It’s mourning dress. It’s hardly surprising if it’s dowdy.’

‘Oh, damn. Stupid of me! Forgive me?’

He always wanted to be forgiven immediately. He could never bear to be in the wrong.

‘Poor Judith. May their memory be a blessing…’ It took me a moment to recognise the words. A phrase of consolation. People had said it to me, years ago, when Father died. People had said it to Toby, but he’d cut them off.

And Sam shouldn’t say the words to me, of course. That was perverse, monstrous. He was both the only person who could comfort me, and the only one who couldn’t.

‘Judith – I’m so sorry, to have to ask, but – who’s passed away?’

It had been so little time since I’d pulled him from the lake that I hadn’t even caught my breath properly. How could things have become so strange, so quickly?

‘Is it someone from your family? Not Ruth, you swear it? No! Who?’

My face scorched as the fire flared. I found the words to tell him who I mourned.

‘It’s you.’

* * *

My grotesque announcement set Sam off on a horrible volley of coughing, his whole body rejecting the news. I took advantage; insisting that he have a handkerchief and a glass of water, I ran downstairs to fetch them both. Busy in the kitchen, I could hear Sam choking. It put me in mind of a curse, as if snakes and toads were struggling out of his throat. I rushed back with the water, and he drank until the coughing stopped. All the while, I braced myself for his inevitable next question, which he asked as soon as I sat down.

‘Judith, why on earth would you say I was dead?’

I sat in the chair opposite him, but I could only speak in fragments. ‘During the Sully, the midwinter festival. In the river, at Breakwater.’

‘That little village?’ He sounded hazy, night-capped by recollection. ‘What about it? There was a river festival?’

I tried to hold on to clarity. ‘You were there, taking part in the festival, and you fell. You were carried off downriver and we thought you’d drowned.’

‘You all thought so?’ He sat up, eyebrows raised, resolutely un-drowned. ‘I’d believe it of Toby, but…’ As though I was too sensible. I’d made a childish mistake. It was my word against his – no, it was his whole stubborn body against my words. To justify myself, I said: ‘We all thought so.’

‘Oh, no. No, you can’t have. You poor things…’ He curled up again, face in hands, blankets closing over him. When he spoke, his voice was muffled. ‘So Toby thought he’d lost me?’

I couldn’t reply for a moment, because Toby’s mourning had been twisted by his uncertainty. It wasn’t appropriate for Toby to rend his garments while Sam might still be alive. Instead, for the whole of January, Toby had been frenetically busy: writing, revisiting the area, vigorously searching for any sign of his brother. I wouldn’t relate that whole sad period to Sam.

‘Yes. Toby thought you were gone.’

‘Oh, no, that’s simply ridiculous…’ He bowed his head down again, retreated into his nest.

We’d failed Sam, clearly. We should have asked advice. But from whom? Mama had been hysterical. Ruth and I had no allies. Unimaginable, to go behind Toby’s back to ask for help from his associates, or his very austere rabbi.

Sam straightened up again, reached for the coal tongs, an expensive habit. ‘I’m sorry, Judith, it simply seems incredible.’

I could offer physical proof. Crossing to the high shelves where my sister and kept our favourite books of folklore, behind garlands of ivy, I dragged at the first volume of The Golden Bough. It toppled into my hands, and from between the pages fluttered a piece of paper, a long oblong clipping from the Jewish Chronicle, from late in March.

I picked it up from the floor and held it out to Sam.

‘Here.’ I sounded triumphant, without meaning to.

Sam read the newspaper notice without speaking. I knew what it said, more or less. Ruth knew it by heart.

DEATHS: At Breakwater, SAMUEL SILVER, beloved brother of Tobias, in his 29th year. Deeply regretted by his family and all who knew him.

He looked at me with confusion. ‘Did you think so, too?’

‘Yes.’ Why could he not understand? You can’t be dead to a few people and not others. I could show him another clipping, where Mr Tobias Silver thanked people for ‘visits, letters and many kind expressions of condolence’. That had appeared in the Chronicle some weeks later. Did Sam’s slowness spring from his shock, or from some organic cause? My eyes fixed on the smear on his forehead, and the darkening bruise underneath it.

‘Damn it! Ruth as well?’ He leaned suddenly out of his nest of blankets and gripped my arm. ‘How is she?’

‘You were going to be married.’ It was all the explanation I could bear.

‘I need to talk to her right away, as soon as I can. I can’t bear to think of her –’ He sank back. ‘There’s no way to contact Ruth tonight?’

Would the police be able to send a communication? But then Ruth would be woken in the night with a wild tale, and no way to confirm it.

‘We can send a telegram tomorrow,’ I offered. ‘First thing.’

Sam’s eyes narrowed in thought. ‘I shouldn’t… I mean…’ Or was he wincing at my suggestion? ‘Has she forgotten all about me?’

An unfathomable question. ‘You were going to be married! I should send for the doctor.’ I feared he needed medical attention, but I also hoped to place the problem in the hands of some wise elder. If not a doctor, then our rabbi, or even our lawyer. I had no idea how to send for the doctor. I could wake Lucy and ask her.

‘No, no doctor.’ His expression became particularly earnest, promising good behaviour. ‘Please. I merely need a little sleep.’

He probably knew himself best. He could go to his own house and sleep as much as he needed.

‘I have a key for Millstone,’ I said. Millstone was Sam’s house, next door to ours. It was one of a row of identical villas, all small but elegant. If you clambered through the hedges at the foot of Millstone’s garden, you reached our ornamental lake. ‘Can you walk?’

He grimaced. ‘Judith, I can’t go to that house.’

‘But you have to sleep.’ More truly, I had to sleep. But I couldn’t see why he shouldn’t leave. Millstone would be bitterly cold, and not stocked with luxuries, but serviceable. Toby had retained his housekeeper, a gardener and one maid to keep the place up.

‘I really can’t! Aren’t there servants there? Who think I’m…’ His voice dried up in panic.

‘Oh!’ None of the servants lived in, but the maid would arrive at Millstone tomorrow morning and scream when she discovered Sam in bed. What were his choices, though? Should he take a cab to a hotel? He was half undressed and covered in filth. Dukes and earls could waltz into Claridge’s in such a state and demand a hot bath. I suspected that a Jewish gentleman, however respectable, would not risk it. And it would all cost money. Did Sam have any money?

It absolutely wouldn’t be right for him to stay here, in this house.

Waiting for my judgement, he sank further down into his blankets. A giant foundling had delivered himself to my doorstep.

‘You could stay here,’ I conceded. After all, he would have been part of my family.

‘Judith, that’s terribly generous.’

Despite all my uncertainty, his gratitude pleased me. ‘I’ll ready a room for you.’

Leaving the library, I returned to the conservatory to gather up his cold and sodden clothes. There were plenty of guest rooms – we were an unusually small family – and some rooms had baths where I could deposit Sam’s wet clothes. I carried the wet burden up the stairs, past the door of my sister’s room. If only I could go in and find her there. But it served me right. I’d gone to such lengths to get rid of my family, I couldn’t conjure them back as soon as I needed them. I pushed open the door to the first guest room.

The room was full of ghosts. White figures towered over me, brushed my face.

I flinched, then recognised them for what they were: long white dust sheets, draped to protect every piece of furniture. The maid had been very thorough. I dropped the squelching bundle of clothes in the bath, then drew the dust sheets off so that they rippled to the floor. In deference to our guests, it was a dull room, untouched by my and Ruth’s magical hands: no murals, no gilded scrolls on the furniture, no patchworks. And there hadn’t been a fire in the room for months. We’d had no guests since Sam died. For the second time that night, I crumpled old newspapers, propped kindling in a pyre. Then I broke three matches with my clumsy, clammy fingers. When the paper caught, though, and the blue line of flame snaked along its edges, it was beautiful. I waited for the sticks to catch, herded some pieces of coal close and hoped it would thrive.

When I returned to Sam he’d buried his face in his hands again.

‘There’s a room for you.’ I feared he was crying, but he didn’t make any sound. ‘I’ve lit a fire upstairs.’

He raised his head at that, and gathered his ludicrous robes about him. ‘You’re very kind.’

We walked together up the staircase. Sam’s damp feet slapped on the steps and I tried not to make a sound with my own. When we reached the top, he turned the wrong way, shambling down the opposite corridor.

‘Wait!’

‘What?’ His hand was on my bedroom door, his eyes only half open.

‘Not that room.’ I was desperate for him to step away, and couldn’t tell him why. He would have been mortified to know. I made a pathetic gesture to bring him back, shoo him towards the guest room. ‘That door, there.’

‘But this is my room.’ Then he frowned, looking down. The carpet pattern, a jumble of red and green, alerted him to his mistake. ‘No! Sorry! Not my house. Force of habit. So silly, so similar…’

Millstone was laid out on identical lines to my home. I would never have ventured upstairs there, so had no way to know that Sam’s room was in the same corner as mine. At least he understood his mistake, now, and shuffled towards the correct door.

It felt wrong to go into my room at the same time as him, closing our doors and tucking ourselves up. Too cosy. So I turned back to the stairs instead.

‘Goodnight, Judith,’ he called. He used to call up to Ruth, and to me, as we climbed the stairs at the end of an evening: Good night, ladies; good night, sweet ladies… Always calling from the hallway below. Not coming upstairs, not yet.

‘Goodnight.’

‘Wait…’

He held out his hand. In it was the newspaper clipping, crumpled and dirty. Ruth would be so sad that it was ruined. No, wait, Ruth wouldn’t need souvenirs any more.

‘Is the date correct?’

He pointed to the top of the clipping: March 1893.

I nodded. He’d ask: why did Toby wait so long to make the announcement? What would I say?

‘Then what month is it now? It’s still cold…’

‘December.’

‘But that’s months later.’

‘Yes, of course.’ But there was no ‘of course’ about it. I felt as though I stood on stepping stones in the middle of a dark river. I didn’t dare look down to see what swirled around my feet. It was safe to go from stone to stone, question to question, as he asked them, but one of my steps wouldn’t find a stone, and I’d be lost.

‘I haven’t been here for a long time.’ His voice was puzzled. He was calculating the amount of time that had passed, marvelling at the fact. Why hadn’t he known?

‘Where have you been?’

Sam drew in a deep, proper inhalation. No wheezing, no cough now, thank goodness. ‘I should tell Ruth first. Shouldn’t I?’

‘But couldn’t you just tell me a part of it?’ Sometimes, in myths, you need to ask three times to get an answer.

‘No. I should speak to Ruth.’

He entered the room. I saw his hand move, tossing the newspaper clipping onto the fire. Then the door closed and blocked my sight.

* * *

The garden was frosty, still, but I welcomed the clarity. Pulling on a pair of boots, I had gone hunting for my lost shoes around the iced lake. It glowed white, and from the black hole in its centre a web of cracks led outwards. It was already refreezing, the dark water dimpling. It might be solid by morning. I gazed into it as though that was where Sam had come from, bursting upwards. But he’d been walking on the far side, first.

I paced around the small lake to the bushes from which Sam had emerged. By moonlight I couldn’t see any broken twigs. There was crushed grass, but I followed it a few paces, then the bushes were too thorny, and I was still chilled from the lake water. I retreated, retracing Sam’s steps.

Why hadn’t Sam come to the front door? Why had he ended up here? You could reach our garden from the street, if you fought your way through a narrow alley down the side of our house. Had Sam knocked at our front door, had no answer and come to find me?

I was standing back where I’d started. And here were my shoes, half buried, dirtied past recognition. I laid them by the stone bench, planning to collect them the following day. Rolling around on the grass had been the wineglass, and the jam jar with a candle stub. If I could find them and replace them in the scullery, that might close the ritual, which otherwise would hang frayed and unfinished in the air.

I stumbled around and by good fortune my foot struck the wineglass, and as I picked it up, I heard feet pacing in the garden next door. For a moment I fancied it was another person come back out of the lake, someone else supposed to be dead. But then I heard the back door of Millstone shut, and watched a weak glow move up past the staircase windows, settling in an upstairs room. Probably the housekeeper, lingering late, come out to investigate the noise of Sam’s accident. It had been the right decision not to send Sam back to Millstone.

Then a sharp crack, as the back door of my own house slammed.

I spun round, expecting Sam. A pale oval face – not his – drifted down the path towards me.

‘Something wrong there, miss?’

It was Lucy. Her voice had a West Country burr to it, often close to a growl of exasperation. Lucy had often played nursemaid to her younger sisters and brothers, back in her own large family. Freed from that drudgery, she took the same tone with our family: frustration and resignation, at war with one another.

I could only just make out her features, and her curly reddish hair around them. Below that, she was a lumpish silhouette, having wrapped a quilt right round herself, over her nightgown. She was annoyed at having to tramp out into the cold. I would have to tell her not to go about like that, now there was a man in the house. No, goodness, I couldn’t tell her that at all.

‘I heard someone in the garden,’ I lied.

‘Bain’t nobody in the garden, miss.’

‘I see that now. I must have mistaken what I heard.’

‘There’s nothing to hear!’

‘I know!’

We were shouting at one another. Why? We weren’t even disagreeing. We were always getting off on the wrong foot. She’d seen the wineglass in my hand, and she was annoyed at my tippling. Or because I made work for her by scattering kitchen items around the grounds. She was only a little older than me, but all her bones were practical.

‘The grass’ll die if you walk on it,’ she pointed out. A dig at me as a city girl, divorced from nature. I stepped onto the gravel path rather than argue.

Lucy stalked off towards the house, too quickly, with too much risk. I needed to keep her away from the bedrooms, away from Sam. ‘Use the back staircase, won’t you?’ I called after her.

‘I always do, miss.’

She’d heard it as a reprimand, a reminder to stay in her place. Marvellous. The door slammed behind her, echoing across the garden.

To keep myself from trembling, I reached out to touch the nearest tree. The bark was obscured by ivy, tenacious stuff which thrived in our neglected garden. Insinuating my hand past the leaves, I took hold of a woody stem, and pulled myself in to lean against the tree trunk.

Poor Sam. Poor, terrified man. At least he was safe home. A line of poetry ran through my mind, a poem of which Ruth had been fond: Home is the sailor, home from the sea, and the hunter home from the hill.

Then I thought, quite suddenly, as though they followed on from the sailor and the hunter: long-lost brother, prince, imposter. Figures from folk tales, men who arrive in the night.

* * *

Sam had first arrived in our house two and a half years ago, in summer and in broad daylight.

The front bell had rung while I’d been sketching in my bedroom, and I’d scrambled down to answer it. Mama rarely invited anyone to our house. While Father was alive, we’d been part of a mishpocha, a great archipelago of families with an ebb and flow of social obligations: card parties, shopping trips, dinners and dances. But since his death, Mama had not gone much into society; her friends were few, and despite living in London for twenty years she was conscious of her accent. Ruth and I still mourned our father, but we did make visits. Father’s mentors, who had helped establish him in London, treated us to tea and advice. Our friends the Isaac sisters, Rose and Leah, recruited us to play music with them, cheerfully and badly. But we hadn’t been hosting, and were growing hungry for visitors.

If I could answer the doorbell before our maid, I could overrule Mama and invite the visitors into the house myself.

I ran helter-skelter down the stairs, believing the hall would be empty. Instead, I saw men, two men, complete strangers. The maid had already let them in, and abandoned them while she went to tell Mama.

A stocky young man with a neat dark beard, first of all. He scowled up at Father’s wall of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. The paintings showed a parade of knights and kings, quite unfashionable, with gaudy sorceresses and sentimental half-clad mermaids. Typical bad art for a grocer like Father. But I was so fond of them, and irked by the stranger’s scowl. He was very solid for a man not yet thirty, like a miniature banker. I could imagine him ten years older, but not ten years younger.

Around him paced another unknown young man, as restless as if he had stolen all his companion’s vigour. He glanced up and down repeatedly, his dark fringe flopping over his bright brown eyes. (Later we would hear how his ancestors had come from Portugal, like the Mocatta family, which we found very distinguished and romantic.) He was clean-shaven, an oddity when every college man I knew at least tried for a moustache.

As I came to a halt on the stairs, the lively man stepped forwards.

He said he was Samuel Silver, and his younger brother was Toby, bachelors both. Toby turned away from the paintings to greet me gruffly but with all politeness. He kept scowling, and I realised it might not be a judgement on Father’s art, but his habitual expression.

Samuel continued to tell their story: they’d sold their family concerns in Manchester, moved south to London and snapped up the house next door. His tale of adventure ended on a conventional note: ‘We’ve come to leave our cards. Now that we’re neighbours.’

I reached over to take his carte de visite, but he kept speechifying, gesturing. Their house would be repainted, he said, top to bottom; he mimed the top, the bottom and the paintbrush, and he wouldn’t let me take the card.

I snatched the card from him. Which was fiendishly impolite, but I felt exhilarated, not ashamed.

Samuel fixed his dark, quizzical eyes on me. ‘Sorry if there’s any noise from the house. Or trouble.’ He rolled the word ‘trouble’ around his mouth.

Now I was certain that he was trying to sound intriguing. But he’d hired paper-hangers, not set up a pirate den.

I looked down at the card I’d seized. It listed no profession – the brothers were not in business, as Father had been, but of a better class (as were many of our neighbours). The photograph on the card showed Samuel leaning against a marble pillar, and it caught his easy way of standing, but his features were no more than a tea-coloured thumbprint. I looked up at the original, to compare.

Sam examined me in return.

His brother, Toby, coughed pointedly, and said: ‘Miss Sachs, might your father be at home?’ He was embarrassed to be idling here without a proper introduction.

‘My father has passed away,’ I said, and saw him exchange one kind of embarrassment for another. ‘But would you be able to stay and take tea, with Mama and my sister?’

Would they like us? I’d totted up the odds shamelessly. Men often liked Ruth’s sweet nature. Mama, as well, was still cordial company, and her reticence at speaking to strangers only allowed Ruth to shine brighter. I didn’t ask myself: will we like them? Sam was dashing, Toby solid. I did speculate about their provenance, but only because the coming of a new family would normally have provided conversation for weeks around the archipelago. Particularly two bachelors, of the better sort. We’d apparently trumped Mrs Leuniger, and the other matriarchs from the Upper Berkeley Street Synagogue, as the first to meet the brothers.

The newcomers did like us. We gathered in the conservatory; Sam made Ruth properly laugh, bowing her head, and coaxed Mama into conversation. Our guests didn’t remark on the staleness of the cake.

I didn’t know then who Sam was, what he’d been doing. I didn’t know him, as they say, from Adam. He could have been travelling, swindling or murdering for ten years. Back then, my lack of knowledge was a delightful opportunity.

Now I knew Sam very well. Only a single year of his life was hidden from me. How different was this ignorance, and how much more weighty. What had he been doing? What had he seen?

WEDNESDAY

The church clock struck eight, and my head hurt as usual, but the ache had a different timbre. I felt muzzy, unsure of where I was – at home? In the cottage at Breakwater?

Into my mind’s eye came a picture of the children playing in the river at Breakwater. Balancing on unsteady stepping stones to cross the river on a dare. Skipping halfway out, sure-footed, they’d then look down and lose their confidence. The river’s movement would fool them that they were already falling. They’d lean over to compensate and pitch into the water. They always fell in the same direction.

Why had that scene occurred to me? Why did my room smell of river water?

I sat up in bed, saw my fingernails were grimy with earth.

I unwound myself from the mound of quilts, blankets and coats that served for my bedclothes. I used them for warmth, because coal was so costly, even though it meant I was flattened nightly by a heap of cloth, like an inverted Princess and the Pea. Extricated from my bedding, all my muscles smarted. In the dim light, the mirror confirmed a crop of new bruises, plum fingerprints on my hip and shoulder.

Moving to the windows, I hoped to see the frozen lake, but ivy blocked my view, covering the outside of the window with dark leaves. Pale stems, clinging and hairy, longed to invade my room. The gardener had neglected to hack them back. Peering between leaves and stems, all that was visible was a wall of white mist.

Sam was in my house. Sam had come back to my sister. I had to dress, and find him.

My formal frock was filthy, ruined at least temporarily, driving me to pull on an old aesthetic gown of wine-coloured velvet that Ruth had helped me to make. It would do for today. Glancing at my reflection to check I was respectable, I was surprised how well I appeared: less subdued, more purposeful. The dress fitted me as well as it ever had, its generous cut hiding feast and famine alike, and had a robe-like dignity. I hoped it wasn’t obvious that it had once been a curtain, from the French windows in our library. The other curtain of the pair still hung there. The air drew deeper into my lungs without the constriction of my mourning clothes.

I closed the wardrobe door so gently it wouldn’t have startled a clothes moth. I tiptoed down the staircase, and the ladies in my father’s paintings regarded me with sympathy. They knew disloyalty, secrecy, the concealment of fear. Ruth and I had grown up playing at Lancelot and Guinevere, not quite understanding the details of their betrayal but feeling their dread and acting out their punishments. And red-cloaked Imogen, from Shakespeare, whose wifely fidelity had only attracted horrors. There were no contented couples in all this art. Perhaps Father had unintentionally inducted Ruth and me in romantic unhappiness. But that was all mended, now Samuel was home.

Clothed and clear-headed, my mind turned back to the insistent question. Where had Sam been?

It was right and proper that he tell his story to Ruth first, as he’d said. That was why he’d stayed silent.

No, I was his host, I’d saved him. Couldn’t he hint to me, couldn’t he show me the lightest sketch?

I peered into the library. Lucy had intervened: grate swept clean, patchwork quilts hanging straight, the chairs no worse for wear. No cups on the desk, no mud on the floor. She must have risen early to tidy. The longstanding cobwebs were untouched, though, as were the heaps of holly and teasels that Lucy quite reasonably refused to dust, claiming they were too prickly.

I crept on, down the back stairs to the kitchen. I was distracted by the idea of Sam, during his absence, working at interminable fairy-tale tasks to lift curses: weaving straw into gold, nettles into shirts. As I turned into the kitchen I shook them all out of my head.

A tall figure stood holding a bread knife.

‘Morning, Judith! I helped myself, so I wouldn’t have to disturb you.’ As soon as he moved, careless and graceful, he couldn’t have been anyone but Sam. And Sam was always hungry. Half a loaf lay sliced on the table in front of him – no plates. He waved the knife in lazy circles. ‘Might I have something to put on the bread, dear Judith?’

I couldn’t find my tongue, but I fetched a jar of jam from the larder.

‘Wonderful! An excellent breakfast. You’re very kind. Do you mind if I –’ He started to spread the jam using the bread knife. ‘Sorry, bad manners. It drives Toby wild! You know that little angry face of his. Doesn’t show respect, he’d say. Forgive me.’ His lip curled in laughter, inviting me to share his amusement. He eagerly anticipated being forgiven. ‘Could I fix you a slice?’

He’d washed the mud from his hair, and his fringe fell in exactly the way I remembered. Except his forehead had a swollen lump on it crossed by an ugly scab. I was surprised how coolly I eyed it. Where was my pity for him? Where was my gladness?

Where had he been?

I found I was furious with him. How cruel, to disappear without a word, and let a whole family mourn for you! To let a fiancée mourn you, and become a widow without having been a wife. Sam could be capricious – Toby told us he’d once gone to Vienna on a whim and not come back for months – but I hadn’t considered seriously until this moment that he might have abandoned Ruth. Had he thought of her? Had he brushed away the thought? Brushing away guilt a dozen times a day, that was a proper fairy-tale curse-task.

My throat closed up and I had to cough before I could speak.

‘So you’ll be on your way back to Millstone,’ I managed. ‘Now that it’s light.’

‘Perhaps,’ he said.

‘You can send a telegram from the post office, at the end of the next street.’

‘You mean that I should tell your sister?’

‘And your brother, yes.’ Was I glaring at him? I tried to smooth my brow.

‘I suppose I ought.’ He licked jam off the side of the knife. I’d have found it endearing, before, but now I was inclined to side with Toby. No respect.

‘There’s nothing to stop you. Is there?’ I retrieved the jam and spooned some onto my own slice of rye bread. The things I nearly spoke were so bitter that I needed to sweeten my mouth.

‘No. I don’t have any other duties, being dead.’

He was trying to charm me with jokes, but severity rose up in me. ‘Not being dead, you do have duties.’

‘I know I do!’

‘Oh? If you’ve been alive for all this time…’

‘If?’ He spread out his hands, incredulous. ‘Judith, that doesn’t even make any sense.’

I kept talking, over his protests. Shouting, in fact. ‘If you’ve been alive, I don’t know why you didn’t tell us, tell Ruth. That was your responsibility!’ Sharper words were striving to get out of my mouth: jilted, bolted