8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

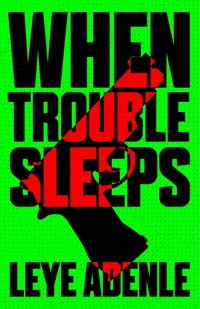

Amaka Mbadiwe returns in this gripping sequel to the award-winning Easy Motion Tourist, and trouble isn't far behind her. The self-appointed saviour of Lagos' sex workers, Amaka may have bitten off more than she can chew this time as she finds herself embroiled in a political scandal. When a plane crash kills the state gubernatorial candidate, the party picks a replacement who is assured of winning the election: Chief Ojo. But Amaka knows the skeletons that lurk in Chief Ojo's closet, including what took place at the Harem, the secret sex club on the outskirts of Lagos that he frequents. Amaka is the only person standing between Chief Ojo and election victory, and he sends hired guns Malik and Shehu after her. Caught in a game of survival, against a backdrop of corruption, violence, sex and sleaze, Amaka must find a way to outwit her bloodthirsty adversaries. Leye Adenle pulls back the curtain on the seedy underbelly of Lagos once again in this gritty and compelling thriller. Nominated for an eDunnit Award 2018

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

WHEN TROUBLE SLEEPS

Leye Adenle

For mum and dad

Contents

Prologue

‘Have you ever been on a private jet?’

Chief Adio Douglas stretched his hand over Titi’s shoulder in the back of the Mercedes S-Class. Titi shook her head. ‘You will experience it today,’ he said.

Titi curled her feet up underneath her, careful not to scratch the black leather with the heels of her Manolo Blahnik sandals, and she folded her body into his arms. She looked up at his face. ‘Is that the surprise?’

‘No. I’ve got an even bigger surprise for you.’

‘Where are we going? Should I have brought my passport?’

‘We’re going to Abuja. To the Villa.’

Titi unfurled herself. ‘To Aso Rock?’

‘Yes. I am meeting with Mr. President himself.’

‘Wow. I will meet the president?’

Douglas laughed. ‘No, my dear, I will meet the president. You will wait for me in the presidential suite of Transcorp Hilton.’

‘Is that the surprise?’

‘No, baby.’ He pulled her back onto his chest and stroked her arm. ‘It’s a big surprise.’

Police officers at the gate stood aside and saluted as the limousine drove past them onto the Execujet secluded ramp close to the private wing of Murtala Muhammed International Airport.

Agents of the Department of State Services, who had been riding ahead in a Ford Explorer SUV, jogged alongside the Mercedes holding their Israeli TAR-21 assault rifles in both hands, buttstock to the shoulder and muzzle tilted to the ground. The limousine stopped close to the upturned wing tip of an Embraer Phenom 300. An agent scanned the shimmering the tarmac littered with private jets before opening the chief’s door.

Douglas’s white agbada billowed in the kerosene-laden wind as he pulled it over his head. Titi, in her black tunic dress, walked around the armoured car to join him. The boot of the Mercedes opened and DSS agents fetched Douglas’s briefcase and Titi’s weekend bag.

Just behind the cockpit, the aircraft’s door began to open downward. Through her sunglasses, Titi watched as the door stopped its descent a few inches from the ground. She looked at Douglas.

‘Can I take a picture?’

He smiled. ‘Sure. So long as I’m not in it.’

She turned her back to the aircraft, held her phone high in front of her and pouted. On the screen she saw the pilot climbing down the steps.

‘Didn’t you say your ex-boyfriend is a pilot?’ Douglas said.

Titi’s hand dropped to her side as she turned to look back at the pilot.

The young man was standing by the steps with his hands held behind his back, his eyes hidden behind his Aviators and his head slightly tipped upwards. He stood still like a soldier.

Douglas placed his hand on Titi’s back. ‘Let’s go,’ he said. Her body resisted his push. ‘Is anything the matter?’ he asked.

Titi turned away from the pilot and looked up at Douglas.

‘Is anything wrong?’ he asked again.

She slowly shook her head.

‘OK then, let’s go. I don’t want to keep the president waiting.’

Douglas and Titi waited for a DSS agent who had carried their luggage onto the plane to descend the steps, then with his hand on her back, he ushered her in front. The pilot remained still.

‘Wait,’ Douglas said.

Titi stopped, her hand on the cold handrail.

‘Titi, meet our pilot for today: Captain Olusegun Majekodunmi. Did I get that right?’

The pilot nodded.

‘Olusegun, meet my girlfriend, Titi.’

Titi did not look at the pilot. The pilot nodded but did not look at Titi.

They sat in the middle of the narrow cabin in beige leather seats facing each other. Neither spoke during the jet’s take-off and short climb. Titi kept her sunglasses on, staring through the window.

‘Are you OK?’ Douglas asked when the jet had levelled out.

‘Did you know?’ Titi said. A tear appeared below her sunglasses before dropping onto her hand.

He unclasped his seatbelt and leaned forward.

‘You knew,’ she said, removing her sunglasses and placing them on her lap. The lenses were wet.

‘In a couple of months, I will be the Governor of Lagos State. You will come and live with me in the State House.’

‘You are married.’ More tears ran down her face.

‘Yes. And so what?’

‘He is my fiancé.’

‘And who am I to you? A sugar daddy?’

‘You are married, Chief. You are married.’

‘You lied to me, Titi. You lied to me. But I forgive you.’

Titi buried her face in her palms.

Douglas held her hand, but she slid out of his grip.

‘Why?’ she said, looking up at him, mascara leaking into the powder beneath her eyes.

‘I will be governor; he is just a pilot. A glorified driver. I want you to choose now. Do you want to come with me, or do you want to remain where you are?’

She shook her head and turned to the window, closing her eyes to the brilliant sunshine; searching for the window blind.

He stood, leaned over her and reached for the blind. Looking out of the window his face creased. ‘That’s strange,’ he said.

She looked out of the window to see what he’d seen, then she looked back at him.

At that moment, the engines roared, her sunglasses floated off her lap, and she lifted in her seat, her body held down only by the seatbelt around her waist.

Douglas, who had been on his feet, lost his balance, cracked his head against the sidewall and fell to the ground.

Titi became dizzy. Magazines, cups, and a silver tray darted about the cabin as the jet flew nose down and she began to black out.

1

‘He found me.’

‘Who found you?’

‘Malik.’

‘What do you mean he found you? Amaka, what’s going on?’

‘The bastard called me and threatened me. Did you tell him I was looking for him?’

Someone ran past Amaka’s window, placed his hand on the bonnet to stop himself from falling, then dashed between the cars ahead. Something looked odd about his sweaty, shaven head: a huge lump on the crown.

‘Gabriel, I’ve got to go. I’ll be at yours soon.’

Amaka put the phone down, leaned to the side and placed her face against the window to try to see the man that had run past her car, but he was gone. Then, another man ran by her window. She turned around. A lot of people were running towards her car from behind. They were holding sticks and planks, and at least one wielded a machete. She turned to look ahead, holding the steering wheel and leaning forward for a better view. A shirtless torso slammed onto the window on the passenger side, jolting her. The man pushed himself off the car, leaving an imprint of his chest in sweat. He banged on the roof and continued running up the road with the rest, waving a plank above his head. One young man held a tyre over his head; worn smooth with its wire threading exposed. Another held up a five-litre jerrycan of a liquid he was trying not to spill.

More men ran up the road, sliding off car bonnets and using their fists to threaten drivers who protested. Amaka looked back and saw even more squeezing past cars and jumping over bonnets. She called Police Inspector Ibrahim.

‘Hello, Amaka, I’m on my way,’ Ibrahim said.

‘To where?’

‘To the crash.’

‘What crash?’

‘The plane crash. Near your house.’

‘A plane crashed near my house?’

‘Yes. A small plane. Didn’t you hear the explosion? I heard it from the station.’

‘No. I’m not at home.’

‘Where are you?’

‘Oshodi.’

‘What are you doing there? You should be in bed, Amaka.’

‘I’m fine. Listen, there is something happening here.’

‘Amaka, do you understand what I just said? A plane crashed into a building very close to your house.’

‘I heard you, but they are chasing someone and I think they will kill him.’

‘Who is chasing someone?’

‘A mob. They are going to lynch him. You have to get here fast.’

Amaka opened the door and stood on the ledge to see what was happening ahead. The men were gathered to the side of the road. They had caught him.

‘Where exactly are you?’ Ibrahim said.

‘Oshodi market. They are attacking him right now. Come, now!’

‘Amaka, stay in your car. Whatever you do, don’t get involved. Do not leave your car. Amaka… Amaka?’

‘Yes?’

‘Do you understand? Do not get involved.’

‘How soon can you get here?’

‘I can’t come. I told you, I’m on my way to the crash site. Whatever you do, don’t get out of your car. Do you understand?’

‘Sure, sure.’

She hung up and stepped onto the road. The man was now on the floor and the mob was attacking him with improvised weapons as a crowd of onlookers cheered, some holding up camera phones. Amaka closed the door behind her and flicked on her camera phone as she started walking towards the mob.

2

Alfred Rewane Road was blocked. People on the bridge at the Falomo roundabout had exited their cars and lined up along the kerb, some of them pointing out the smoke rising behind the mansions of Oyinkan Abayomi Drive, others recording with their phones. A lot of them had their hands on their heads; some stood open-mouthed, others talked on their phones, spreading news of the plane crash.

Inspector Ibrahim told Sergeant Bakare to kill the siren. It was making it hard for Ibrahim to think. The signal from central control in Panti ordered every available officer to be mobilised. Every available officer. That meant traffic wardens, desk officers, even detectives on active cases. A plane crash in a residential area was enough of a disaster, but this was not some regular neighbourhood; this was Ikoyi, old Ikoyi, where the old money lived.

The smoke looked as if it was being pumped out by a factory, then all of a sudden, a flash and the smoke turned orange. A split second later the sound of the explosion reached the bridge. A woman shouted to Jesus to save the poor souls but there was no saving anybody down there. The irony, Ibrahim thought. He knew these people – the same people who would make a call and divert state resources to guard their homes; people who could get a senior officer relocated to a post in Boko Haram territory for not understanding that the job of the police was to protect the rich. Too often he had been ‘requested to provide officers’ whose job would be to escort teenage brats to parties with even more brats – police officers who could be doing police work but instead carried shopping baskets behind bleached-skinned mistresses. He knew them like only a high-ranking police officer could. Rich criminals, that’s all they were. They represented the cases quashed, the investigations called off, the murders, the extortions, the thefts. These people didn’t need protecting; ordinary Nigerians needed to be protected from them.

Ibrahim climbed out of the front door of the police van. His officers got out of the back and joined onlookers on the side of the bridge. Next to them, a young boy in dirty jean shorts and a brown singlet was the only person with his back to the unfolding scene. A worn travel bag was wide open between his feet. In it, in protective plastic sheets, the self-help books he had been selling in traffic before the crash. He was telling a group of worried-looking motorists and their passengers what he had witnessed. With his hand he demonstrated the moment of impact.

‘It was facing down like this. It come down, wheeeeeeee, then it explode, bulah!’

More people crowded round the boy and he repeated what he had said, his recollection of the moment of impact becoming more detailed and the explosion more impressive. As he spoke, everybody on the bridge turned and looked up. A grey helicopter flew low and fast over them and crossed the lagoon in seconds. It went over the crash site before circling back, tilting sideways, then it hovered loudly, spreading the smoke beneath it.

‘Navy,’ Ibrahim muttered to himself. Early reports placed the crash at Magbon Close; another report had it at Ilabere Avenue – both close to each other, both home to billionaires living in modern multimillion-dollar mansions on plots that once housed colonial administrators. Most of the properties had stayed in the same families for generations; the dynasties of Lagos. The very type of Nigerians who flew in private jets. How ironic. He turned to the officer beside him – a slim and lanky, dark-skinned man with tribal marks fanning out from the tips of his lips.

‘Hot-Temper, take Moses and Salem and go to Oshodi market. Where is your phone?’

Hot-Temper was dressed in the military-style combat uniform of the special anti-robbery squad, Fire-for-Fire. He brought out his mobile phone, an old grey Nokia with a monochrome screen, the characters worn off the rubber keypad.

‘Save this number. It’s Amaka. She said they are about to lynch somebody there.’

‘For Oshodi market? Wetin she dey do there?’

‘Who knows? You are not going to get there in this traffic. Take okada.’

Hot-Temper saluted his boss and turned around to scan the traffic. A line of motorcycle taxis was parked between stationary cars, their owners close by watching the helicopter hover over the crash site.

‘Be quick,’ Ibrahim said as Hot-Temper walked towards an okada. The three officers were commandeering motorcycles from young owners who did not have driving licences and who knew better than to protest too much with police officers. ‘And follow her wherever she’s going.’

Hot-Temper waited for a boy to pull his okada motorcycle out backwards from between parked cars and turn it round in the cramped space on the bridge. Hot-Temper swung his AK-47 over his back and mounted the vehicle. The boy held on to one handle and Hot-Temper raised his hand as if he was about to slap the boy.

‘Come to Bar Beach Station tomorrow morning to collect your okada,’ Ibrahim shouted to the boy. ‘Hot-Temper, call me when you see her, OK?’

Hot-Temper kicked the machine to life and revved.

The helicopter flew back the way it had come. Everyone on the bridge ducked as it passed overhead, then arched their necks to follow it as it disappeared.

‘We are walking,’ Ibrahim said to the two remaining officers. He tapped on the bonnet of the van. Sergeant Bakare began to open his door to get out but Ibrahim gestured for him to remain. ‘Meet us there,’ he said, and started down the bridge with his officers.

3

Somebody emptied a jerrycan of petrol onto the man, now immobile and bloody on the road. Another struck a match.

Black smoke rose with a swoosh and an orange flame licked his body, trapped in a burning tyre that had been forced down to his waist, encircling his arms. He leapt from the ground as the fire spread. The crowd backed away from his burning mass, kicking him and breaking planks of wood on his back. He fell to the ground, then he stopped moving and the fire engulfed him till all that was left was a smouldering black figure supine on the asphalt road.

Amaka held her phone in front of her pushed through the men surrounding their kill. The fumes from the burning tyre stung her eyes, the smell of cooking flesh turned her stomach, but she continued forward. The murderers and onlookers, feeling her shoulders push them out of the way, tarried to budge, but the sight of her, her clean smart clothes, her neat hair, her pretty, solemn face, her indifference to them, threw them and they retreated, giving her passage, because she did not belong among them. She confused them, perplexed them, mesmerised them, and rendered their murderous energy ineffective.

The killers formed a circle around their victim. Amaka, with her back to them and facing the dead man, recorded their faces across the rising smoke, pretending to be recording their victim, and like this she worked the circle, her back to the people, her face to the bonfire, her phone capturing the culprits’ images.

A woman was fighting to get through the crowd, screaming, crying, clawing, snatching and grabbing at bodies in her way, dodging an elbow here, absorbing a repellent jab there. She looked like she was in her twenties. She was slender and tall, her dark-chocolate skin smooth and shiny, her hair short and tangled and browning at the twisted tips. She was in a white flannel skirt with a large rose embroidered on the front, a white sleeveless tube top, a pair of red pumps, with a red scarf around her neck and red coral earrings.

She broke through and ran towards the body that was too late to save. Amaka watched her through the screen of her phone. Men grabbed the woman to stop her from reaching the fire, but another group tried to snatch her from the ones trying to save her and appeared to be dragging her towards it.

A lanky man held a tyre over the girl’s head, attempting to get it round her body but other hands worked to stop him.

Amaka tucked her phone into her skirt, ran past the fire, feeling its heat on the side of her face, and grabbed the belt of the man attempting to put a tyre around the woman. She yanked him until he fell backwards. He dropped the tyre and it rolled towards the smouldering body.

Another man was holding up a metal pipe, trying to get a good aim at the girl’s head. Amaka grabbed his hand and he swung round, his fist bunched, but Amaka thrust her knee into his groin before he could deliver the blow. As the man collapsed onto the floor, Amaka and the young woman locked eyes. The woman was being dragged away into the crowd and she stretched out her hands to Amaka, her eyes wide and unblinking, mouth open. Her fingers stretched outwards as if they could somehow bridge the distance between her and Amaka; as if touching Amaka was all that was needed; as if Amaka was the one who could save her and even her dead friend. Amaka stretched her hands towards the girl as splinters of wood flew past her face and tiny sparks danced before her eyes, obscuring her vision. Her knees gave way and she blacked out.

4

A man with sunken cheeks, his faded brown Ankara outfit loose around his gaunt frame, looked around the crowd before stooping to the ground and picking up the phone he had seen fall from the woman trying to fight the men.

As he stood, he looked around before putting his hand into his pocket. The phone vibrated. It startled him, but nobody noticed. They were too busy filming the thief they had caught. He looked down at the screen of the ringing phone. ‘Guy Collins.’ He looked at the woman the area boys had knocked out. He looked back at the phone. He frowned at the sky; at God who had seen him stealing the poor woman’s property, and he answered the call.

‘Amaka, where are you?’ the caller shouted into his ear. He cupped his hand over his other ear so he could hear the man over the noise. ‘Amaka? Amaka?’ She was Igbo. He was Igbo. He bit his lips. He cursed. ‘Hello?’ he said. ‘Who are you?’ He turned his back to the action and began to edge his way out of the crowd.

‘Who is this?’ the man on the phone shouted. He sounded like a real oyinbo, not just someone with an oyinbo name.

‘Where is Amaka?’

‘Are you her friend?’

‘Yes. Where is she?’

‘You better come here now, now. They are going to kill her.’

‘What?’

‘She is on the road here. They are beating her. They are going to kill her.’

‘What are you saying? Who’s beating her? Why are they beating her?’

‘The area boys. They have already killed one thief. They are descending on her now.’

‘What? Who are you? Where is she?’

‘She is at Oshodi market.’

‘Market? Who are you? Can you help her?’

‘Me? What can I do? You better come now-now, before they put tyre on her neck and pour her petrol.’

‘Please help her.’

He ended the call and switched off the phone. It was too late for anyone to help the woman, but God saw that he had done all that he could.

A skinny young man stood with his back to Amaka’s car and looked around. He opened the door and ducked inside. He snatched the handbag from the passenger seat and tucked it under his shirt. At first he walked quickly through the crowd, then he jogged along the road and finally he turned unto a narrow, overgrown passage between the walls of adjacent buildings. He sidestepped mounds of excrement and swatted at flies. He checked behind him before taking out the handbag. There was a notebook laptop inside. It felt light. He tucked it under his armpit and searched for its power adapter.

He pulled out a passport and flicked through its pages before sliding it into his back pocket. He found a mobile phone and its charger, a cardholder, and a wad of pound notes. He stuffed everything into his pockets. He threw out a compact mirror, a lip balm, a nail file, and a bunch of keys, unzipped a side pocket and felt inside. He grabbed the contents. In his palm there was a black SD memory card among four mobile phone SIM cards. He picked up the memory card and inspected it, then looked up as two men walked past the entrance to the passageway. He dropped the memory card and the SIM cards back in to the bag and tossed it away. As he walked away, the bag sank into the vegetation until only its thin black strap was visible, curled over the stem of a plant like a snake hiding in the foliage.

5

Chief Olabisi Ojo groaned and turned over in his bed. He was naked. He put his hand to his forehead and groaned again. The throbbing radiated across his eyes to the back of his head. Lying on his fat belly, eyes closed, he stretched out his hand and swept it over the sheets. He opened his eyes. The lights hurt. He turned his head and looked on the other side of the bed, rolled himself onto his side, paused to let the throbbing subside, then heaved himself up and sat on the edge. The headache intensified.

He looked round the room of the presidential suite at Eko Hotel. His vision was blurred. He tried to focus on the armchair on which his friend, retired Navy Commodore Shehu Yaya had sat, next to a stool cramped with glasses, a dirty ashtray, empty bottles of Star and Guinness, and one empty bottle of Remy Martin - the bottle the girl had brought. Where was she? He tried to remember her name. It hurt to think. Iyabo?

Pain tore through his right eye. Removing his hand from his face, he tried again to focus. He stood and walked out of the bedroom into the living area of the presidential suite. ‘Iyabo!’ he called out.

He wrapped his fingers round his gold watch before checking the time. 7am. He walked to the dining area. ‘Iyabo!’ He looked around. Her clothes were not in the room. He couldn’t see a bag. He wrapped his fingers round his watch a second time. In the bedroom he found his clothes on the ground beside Shehu’s chair. He picked them up and patted the pockets of his trousers; from one, he retrieved a bound, inch-thick wad of one thousand naira notes. He held the money between his index finger and thumb as if he could tell if any were missing. He returned the money and from the other pocket he removed his wallet, spread it apart, and stared at its contents: hundred-dollar notes. Without removing the money, he counted two hundred and fifty notes. Next, he thumbed through each of his credit cards. Confused, he dropped the clothes on the chair. She hadn’t stolen from him. She wasn’t a thief. But she had left without telling him she was going. Or did she? When did she leave? Did they have sex during the night? He reached under his belly and held his limp penis. He couldn’t remember.

He checked the time again, began walking back to the bed, and stopped. His eyes flitted from one bedside stool to the other, then to the floor. He returned to his clothes, picked them up, and patted them down once more. He felt his money and his wallet but nothing in his other pockets. He went to the telephone by the bed, dialled and held the receiver by his side to listen for his phone to ring somewhere in the suite. His eyes fell upon the stool by the chair. He replaced the handset.

Standing over the stool, he looked at the ashtray in the midst of empty bottles and used glasses. Pieces of a SIM card lay atop the ash and butts in it. He bent down for a closer look and saw his phone on the rug near the foot of the stool, its battery and the back cover next to it. As he went down on one knee to pick them up he noticed that the SIM card had been taken out of the mobile.

‘Iyabo!’ he shouted in the direction of the open door. His head hurt as he bent to pull on his Y-fronts and trousers. It didn’t make sense. Did she remove the SIM card and break it? Why? Was she angry with him? Perhaps because he fell asleep? At the club she had made it clear that she wanted to fuck him – and not for money. In fact, she warned him that the deal would be off if he as much as tried to give her any money. She was not a prostitute. Did he get too drunk and try to pay her after sex? Did they have sex? He just couldn’t remember anything. He replaced the battery and back cover and slid the phone into his pocket. Why had she broken the SIM card? So he wouldn’t have her number?

He went to the window and drew back the thick curtain. It was dark outside. Panicked, he looked at his watch again; it wasn’t seven in the morning. He had slept till seven in the evening.

He tried to gather his thoughts. He’d arrived at the hotel around one. Or maybe two. Shehu joined him not long after. Iyabo arrived about 4am. He had met her at Soul Lounge. She did not look like a prostitute; she said she wasn’t one. She spoke with an accent, like someone who studied abroad. She wore a skirt suit; she said she’d come from work, that she was a lawyer.

The last thing he remembered was seeing Shehu off – that was a few minutes after Iyabo arrived – but he strained to remember what happened next.

Pain seared through the crown of his head as he stood up. He groaned, held his head in his palms and sat back down in the armchair. It creaked under his weight. His eyes darted around as he tried to think, then they shot back to the ashtray. With his index finger he searched amongst the stubs and the broken pieces of his SIM card. He turned the ashtray over onto the table. Nothing. He flicked the ash off his fingers and rushed to fetch his phone from his pocket. As he slid off the back cover and removed the battery, it was as he feared: the memory card was missing. An alarm went off in his head. He looked around, pushing his hands down behind the corners of the cushions. On his knees he searched on the floor and under the chair. He pushed himself up onto one knee and shouted, ‘Fuck!’

6

Horns were going off everywhere on Bourdillon Road, cars lined bumper-to-bumper remained static. Exhaust fumes hung heavy in the air. Okada drivers straddling their motorcycles used their feet to move their machines between cars, their handlebars scratching paintwork in the process. A mass of people walked down the road and the traffic police watched from the enclosure of the roundabout under the flyover.

Inspector Ibrahim and the two officers with him joined the throng of people heading towards the crash site. All around them, men with scratchy voices spoke the bastardised form of Yoruba popular amongst Lagos touts. Men shouting and waving fists bumped their shoulders into the police officers as they passed them.

A man pushed past Ibrahim and, after four steps, scratched the road with his machete. Ibrahim placed his hand on the arm of the officer to his right who had begun to raise his AK-47. In front of them, the man was now circling the machete over his head. Ibrahim looked behind. In the midst of the approaching crowd, there was a group of men holding up leafy branches and machetes. A shot went off while Ibrahim was still watching. He jolted. The crowd continued past him and the other officers, unperturbed. Ibrahim had seen where the shot came from. The barrel of the black pump-action shotgun was still pointing upwards.

‘What is going on?’ Ibrahim asked. Among the men walking towards them, one was loading cartridges into a shotgun. The man looked up at the officers and continued loading his weapon. As he passed between them, his shoulder pushed Ibrahim, who had to be stopped from falling by the officer to his side. Again, Ibrahim restrained his colleagues.

Another shot went off, this time closer. ‘Jesus,’ Ibrahim said. The sound of a helicopter made him look up. This time it was a green one. The army. Just as it circled back on itself and hovered, another one flew over the crowd, made a large arch, then hovered opposite the first.

The crowd were marching past Oyinkan Abayomi Drive. They looked like they didn’t know the geography of Ikoyi. The officers went down the drive. It was much less crowded. Two lines of immobile cars, many of them with their drivers still at the wheels, stretched back to where the lagoon began. The trees on the lagoon side partially obscured street lamps that had just come on. A third helicopter flew in.

‘What is going on?’ Ibrahim asked again.

They continued past Mekunwen Road, choosing their route by the position of the helicopters above. At Macpherson, a white Toyota LiteAce bus was parked lengthwise, blocking the road. In front of it, men in civilian clothes, brandishing AK-47s, stood guard. Opposite, civilians and police officers stood with their backs to the lagoon and watched the noisy aircraft.

‘Sergeant,’ Ibrahim called, and beckoned to police officers amidst the onlookers. They were not from Bar Beach police station. They were probably posted to stand guard outside homes in the neighbourhood, Ibrahim figured.

There were four officers in all, one woman and three men, who all saluted and stood in front of Ibrahim.

‘What is going on here?’ Ibrahim said. He read the name badge of the plump female officer he had directed the question to. Fatokun.

‘An aeroplane crashed, sir.’

‘I know that. But who are those men there and why are you standing with the civilians?’

‘They are not allowing people to pass, sir.’

‘Which agency are they with?’

‘Agency, sir?’

‘Are they DSS?’

‘No, sir. They are party loyalists.’

Ibrahim shook his head. It was a euphemism for thugs. He looked at the armed men by the bus. The men stared back. It was illegal for civilians to own assault weapons, but here he was, a police inspector, unable to do anything but watch and pretend not to see. The traffic jam had made it impossible for appropriate security agencies to get to the scene. Other police commands would have received the same signal he received, and in time they would arrive along with FAAN officials; meanwhile he appeared to be the first respondent. With two of his own officers, another five conscripted officers, and only two rifles and his service pistol between them, diplomacy was the only option.

‘Do you know which party?’

‘Sir, you haven’t heard?’

‘Heard what?’

‘The plane landed on Chief Adio Douglas’s house.’

‘Crashed into,’ Ibrahim corrected.

He knew Chief Douglas. Everybody in Lagos knew Chief Douglas. He sat on numerous boards and he was chairman of Douglas Insurance – ‘the insurers to Lagos state’ as Ibrahim once read in a newspaper. His house was on Magbon Close and he was going to be the next Governor of Lagos State. His opponent, a doctor who returned from practising in America, whose name Ibrahim couldn’t even remember, lacked the money, the popularity, and the political clout to run against the ruling party. Chief Douglas on the other hand was a former central bank director and a former finance minister.

‘Was he in the house?’ Ibrahim asked. At least the plane had crashed into just one household, Ibrahim thought, then it occurred to him that Douglas was just one life; there were other lives that could have been lost: his family, his servants, his gatemen, not to talk of the passengers and crew on the plane. As a gubernatorial candidate he would have been travelling with his security detail. Officers who bade their family goodbye in the morning, not knowing they would never see each other again.

‘He was in the plane.’

‘He was in the plane that crashed into his own house?’

‘Yes, sir. They are saying the other party bombed the plane.’

Ibrahim remembered the men brandishing machetes and firing shots. They were the party loyalists, and the men armed with AK-47s, not letting people through, were waiting for them. Reinforcements. Lagos was about to explode.

7

Chief Ojo stepped out of the presidential suite, closed the door behind him and removed the ‘Do not disturb’ sign from the handle. He stared at the glossy door hanger – he didn’t remember placing it there. Downstairs in the lobby, waiting for the woman at the desk to get off the phone, he continued trying to put together the disjointed pieces of the night before, all of it muddled in the haze of his fantastic headache. Iyabo had been on the bed when Shehu left. He couldn’t remember if he followed his friend to the door, out into the corridor, or to the lift.

‘Good evening, sir. How may I help you?’ the woman said, jarring Ojo out of his thoughts.

Ojo placed his key card on the counter. The suite had been paid for. Originally booked for a visiting diplomat, the man had been unable to use it and Ojo had asked if he could have it. All Ojo had to do was pay for the drinks he and Shehu ordered through room service.

The girl typed on her keyboard, all the while maintaining her smile. A printer began to spool out a sheet of paper onto a table behind her. She fetched the invoice and placed it in front of Ojo.

‘What the hell?’ he shouted, reading the total on the bill.

‘What is the matter, sir?’

‘What is this?’ He waved the bill in front of her face.

‘It is your bill, sir,’ she said, uncertainty in her voice as she inspected it.

‘For a few drinks? How much is Star and Guinness?’

‘It is including the charge for the room, sir.’ Her voice became quieter as she spoke, as if retreating.

‘The room has been paid for by the liaison office. Check your records.’

‘But sir, checkout time is twelve, sir.’

‘Yes. I did not check out before twelve, so that makes two nights. Paid for.’

‘Sir, you checked in the day before.’

‘Yes. Late last night.’ He slammed the invoice on her desk.

The girl leaned in closer to inspect the figures. She struck some keys on her computer and took her time to read what was displayed on the screen, comparing it with the sheet of paper.

‘No, sir. I mean ….’

Ojo snatched the invoice from her and glared at it.

A short man in a black suit, white shirt and a kente tie appeared beside Ojo.

‘Good evening, sir,’ he said. ‘My name is Magnanimous. I am the concierge. What seems to be the problem?’

Ojo looked at his watch. At the date display.

‘Are you OK, sir?’ Magnanimous said.

‘I have been here for two days?’ Ojo said.

‘Yes, sir,’ Magnanimous said.

‘Two days.’

‘Yes.’

‘I have been in the suite for close to forty-eight hours?’

‘That is correct. What is the problem?’

‘I thought…’

‘What, sir?’

‘Nothing. Nothing. Do you accept dollars?’