11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

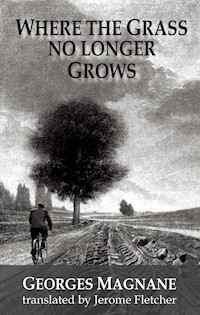

Where the Grass no longer Grows is based on events at the French village of Oradour-sur-Glane in June 1944 when the SS massacred 642 men, women and children. This novel, the only fictional recreation of the massacre, follows the fate of a number of characters both inside and outside the village as they become aware of and respond to the unfolding horror.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Dedalus European Classics

General Editor: Timothy Lane

WHERE THE GRASS NO LONGER GROWS

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited

24–26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 912868 83 4

ISBN ebook 978 1 912868 98 8

Dedalus is distributed in the USA & Canada by SCB Distributors

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

[email protected] www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W. 2080

[email protected] www.peribo.com.au

First published in France by Albin Michel in 1953, republished by Editions

Maiade in 2016

First published by Dedalus in 2022

Où l’herbe ne pousse plus copyright © Editions Maiade 2016

Where the Grass no Longer Grows translation copyright © Jerome Fletcher 2022

The right of the estate of Georges Magnane to be identified as the author & Jerome Fletcher as the translator of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Elcograf S.p.A.

Typeset by Marie Lane

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

THE AUTHOR

Georges Magnane (1907–1985) was the pen name of René Catinaud, born into a farming family in Limousin, central France. He went from there to the Ecôle Normale d’instituteurs in Paris before completing his studies in Oxford.

As well as being a teacher and novelist, Magnane was a journalist (he covered the 1948 London Olympics for Sartre’s L’humanité) a pioneer of the sociology of sport in France, a translator (notably of Updike, Nabokov and Capote), and a scriptwriter for theatre and film.

THE TRANSLATOR

Former real tennis professional and elver catcher, Jerome Fletcher was Director of Writing at Dartington College of Arts and Associate Professor of Performance Writing at Falmouth University. He has published novels and poetry for children, translations, and experimental digital texts, as well as performance works. Along with Alex Martin, he has produced several titles for Dedalus including The Decadent Cookbook, The Decadent Gardener, The Decadent Traveller and The Decadent Sportsman.

He now lives in France near Limoges.

FOR APHRA

WITH ALL MY LOVE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The translator would like to thank the following who have provided invaluable assistance and feedback. Dr Thomas Bauer, Jean-Christophe Chaumeny, Prof Thomas Docherty, Marie-France Houdart of Editions Maiade, Edward Klein, Pierre Sourdoulaud, Barbara Bridger, Alex Martin. And especially Amy Lewis.

FAMILIES

CONTENTS

PART 1

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

PART 2

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

PART 3

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

PART 4

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

PART 5

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

PART 6

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

PART 7

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

PART 1

CHAPTER 1

Not for one moment did Jean Bricaud think that the war would arrive at his door – the door to his peaceful house built a short distance from a peaceful village at the edge of a valley where it had taken millennia for a passage to be hollowed out through the most ancient earth. It was the toughest, the most solid of houses, better protected than any other against the vagaries of volcanoes, plague, war and famine.

On that June day in 1944, it was only some time after Jean had heard the rumble of lorries that it occurred to him anything might be wrong. The news of the German debacle that he listened to on the radio every evening came as no more of a surprise to him than the loudly trumpeted announcements three years earlier of their headlong push towards the East; it was none of his business. He had done what he could for his family, for the refugees, for the starving townspeople who approached him; he had filled each day to the brim with exhausting work. So, if there were those who wanted to play with thunder and death, that was their look-out. He wasn’t joining in their game. He didn’t have time. Yesterday’s winners are today’s losers? … that was fine. He gave them a round of applause. He lent a helping hand as and when. But best not to pester him and waste his time. A small contribution, that was ok. A big one, that’s going too far.

He was turning over the hay on his own. He’d never get it done. It was already past lunchtime. That empty feeling which had begun in the pit of his stomach was steadily spreading now. He was feeling it in his shanks and even more in his right forearm with which he gave the rake a quick flick when needed.

In this shimmering open space, crackling with grasshoppers and sparkling with heat, he was feeling a bit lost. And angry. If it weren’t for the anger, he would have already called it a day. The hay could wait, what with weather like this. Annie and his mother went to the market in Verrièges every Saturday. Fine. No problem with that! What with all this ration book stuff, his mother was no longer up to it on her own. At seventy-seven years old it wasn’t easy to comply with all this red tape. But then, it was good for maman, good for her to need Annie now and again. She’d often said that her daughter-in-law wasn’t in the house just for decoration. They don’t mince their words, the old folks … but Gaston! That boy had no reason to wander off to Verrièges. The cocky sixteen-year-old, built like an eighteen-year-old, was old enough to pull his weight, otherwise he’d never amount to anything, useless lump! As soon as he noticed how his uncle Francis had pricked up his ears, he immediately started yelling; “What is it, Francis? What do you reckon’s going on? Maybe they’re the Maquis’ cars. We ought to go and see.” Francis came straight back at him. “Oh, you think so, do you? It’s the Jerries. Lorries and light tanks.” Jean had hoped that would settle the question. Not a bit of it. Francis immediately dumped his rake in a ditch (it was still there, with Gaston’s next to it, the tines full of hay, they’d been in such a hurry. Idle buggers!) He’d said: “It’s not normal for there to be so many. I’m going to see what they’re playing at.” My arse! Jean knew very well what Francis had in mind – a nice little rendezvous at the lake with his Juliette, the mayor’s daughter. Never liked her, that one. She’s got a way of looking straight at you. I’ve never seen her lower her eyes in front of a man. In my day the girls were never like that, even in town. Everything’s going to hell, and fast.

Needless to say, Gaston had followed his uncle. Jean daren’t say a word. If he started, he’d say too much and end up breaking something. He couldn’t bear it – all this talk of planes and cars and motorbikes, talk which Francis had brought with him from the town and which he blew through the house like a wind. Jean had had a motorbike too, of course, but he’d paid for it with his own money, every nut and bolt, from selling on the sly anything he shot or caught with his rod. Mind you, it wasn’t the same. He’d never taken this stuff seriously. For Francis it was a passion, even if he wouldn’t admit it, and if he continued to encourage Gaston, he’d turn out even worse than his uncle. All their mechanical crap! It was obvious what was going on in 1940, when all that stuff flowed out along the roads and lanes. It was like the town was suppurating, stinking, growling, screeching; from time to time it let out a jet of flame and a fart. Must have been something poisonous in the belly of the town! All their transportation, all their planes, their heavy guns and what have you, they were invented to finish things off when they realised the pox wasn’t up to the job. It’s war, right! And Francis, his own brother, followed all the latest inventions. Even put his own shoulder to the wheel. One day he was going to patent some type of motor. He often talked about it. Of course, that was his role, him being an engineer. “Yes …” Jean had explained the previous day to that miserable, short-arsed tutor who wanted to show off, “… my brother’s an engineer. Not just any old engineer. Came top of the class at the Polytechnique, in case that means anything to you, M. Poulard? And is he proud of that, eh? … we would be, in his shoes. And we are, as you see.”

It was nice to have a phenomenal brother, and flattering for sure, but it was no reason to remain on his own in that murderous heat. Rivulets of sweat were forming on his forehead. Now and again they ran across his eyebrows although their course was mostly down his nose, from where large droplets regularly fell onto his wrists and shoes. “Lorries and light tanks … it’s a lot of crap as far as I’m concerned. I wouldn’t get off my arse to take a look at the finest piece of engineering in the world.”

Then all of a sudden he had a thought which, for a moment, dried up the source of his sweat: he had heard the lorries arrive in Verrièges, but he hadn’t heard them leave. What’s that all about?

He quickly searched in the little pocket under his belt where he put his watch. Hang on, hang on! It was nearly two o’clock. Something odd was going on, surely. The women were always home a good hour before this. What is it? What’s up?

He stood for a moment, rooted to the spot, holding his rake at arms-length, its tines pointing upwards. The sweat began to run again, cold and viscous. It took Jean some time to realise how absurd this was: in the midst of this heat, he felt cold. Cold, in June sunshine. Cold in the meadow most sheltered from the wind. Moreover, the row of oaks in front of him were as motionless as a picture in a book. Not a breath of wind stirred in them. Neither earth nor sky breathed. The moment hovered over him, held steady on immense wings.

Jean stood motionless, blinking, torn between a desire to leap into action, to set off, and an equally immediate reflex to do nothing. No. No. Absolutely not. If he carried on working, if he forced his actions and his behaviour to follow their everyday arc, he would drive away any bad luck, he would maintain the continuity of his life.

That was what he was thinking. He was already picturing that first movement where the end of the rake would slip under a tuft of scrunchy grass, but he knew this was turning into a rout. It was like in a legend: far removed from the event and yet at the same time plunged intimately into the very heart of it, he contemplated this field, these trees, the fine scattering of hay, and he found there a desperate beauty totally alien to him. Even his recent surly fatigue was becoming dear to him, because it felt like a fragment of treasure lost forever. He would have given anything for that desire for anger to rise in him again. He would give it a try anyway. Come on. Quickly. He had to give it a try. No time to lose.

He took off across the hay. He ran as lightly as he had as a ten-year old. And he really felt like he had returned to that ferocious age when everything was possible and when slaughter and death framed his daily imaginings. Except that, at ten, death held no real fear for him. Death was a mere formality like any other, a bizarre comedy that you weren’t allowed to laugh at. Now he had learned real fear. Now he shuddered to feel that energy again in his legs driven by that constant, light-hearted terror of yesteryear.

With a modicum of force he pushed open the gate, still rotten after twenty years but holding together. It squeaked like it had always squeaked, with a sniggering, obliging tone. He had slowed down to hear this friendly caricature of a voice. At the same time, through an open window he heard the sound of his mother and father squabbling. This was also familiar and reassuring to him; indescribably reassuring.

Jean wanted to afford himself one last moment of childish cowardice, of happiness … he went into the house looking angry, as if nothing had happened, and actually convincing himself that nothing had happened. How good it felt to be a little boy again to whom nothing could happen! In much the same way as the gentle, faded gaze of his mother had a calming effect on him, so too did the pitiless, piercing eagle eye of his father. Ok then! Get angry, get angry with me then, tell me off for making a noise or being late! Get really angry so that I can feel the true heat of the sun a bit, so that I stop shivering and feeling myself slide towards that black abyss.

But when he came in the old couple suddenly fell silent. His father, who was hunched over the newspaper, rustled the pages and looked guilty. His mother decided not to put down the lettuce leaf she had been cleaning.

‘Why are you shouting like that?’ Jean asked in a scolding tone. ‘You can be heard a hundred metres off.’

‘Oh, nothing,’ his mother said. ‘It’s him, banging on as usual. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’

Jean wanted to put on a gruff tone. But he couldn’t.

‘Show me the paper,’ he said.

Before Jean had even found the page where his father’s long, hard nails – those grooved nails which he sometimes cut for him – had dug into the paper, he had understood: he had been reading the infamous denial put out by the occupation authorities. That morning, the postman had talked to him about it when he passed him on the road. Then a neighbour had left the patch he was weeding and crossed two fields, his own and Jean’s, to come and ask him what he thought about it: ‘They haven’t really done that, have they? It’s not possible. That’s what you think too, isn’t it? You realise they’re saying this is getting closer every day. They set fire to Tulle, left Guéret in ruins. Now the shooting’s moved to Argenton; and the first ones to be gunned down were the gendarmes, for not being fanatical enough. Still, it’s unbelievable. This denial, what do you think?’ Jean said nothing. He had not read it and he didn’t want to read it; any more than he would have wanted to listen to an account of the massacres in Tulle and elsewhere.

And now …

His father looked up at him. Jean met his gaze and for the first time realised that he had an old man in front of him, an ancient old man, who in turn was looking for some support. At ninety-three, he might have expected it … all the same, now was not the time. It seemed like a betrayal.

‘I’ve got to go and see,’ he said abruptly.

At once, his father and mother stood up. His father’s shaking hand groped along the wall for his stick.

‘Stay here you two. What’s most important is that I’m going to bring them back.’

His voice was so lacking in confidence that he did not expect to be obeyed. In fact, his father muttered something, found his stick finally and set off towards the gate with a sprightly step which Jean had not seen in forty years, not since he himself was struggling to put his first steps together. This did not surprise him. He had given up being surprised, surrendering in the face of the inadmissible. He was on the verge of panic.

Mechanically, he looked for the identity disc for his bicycle. He could not find it and he continued on his way. As if he really needed an identity disc! Just the thing to waste your time on at a moment like this! He held back a roar of anger and dashed towards the bike shed.

He had gone through the gate and was set to kick it shut, as he usually did. His mother gestured to him to get going.

‘I’ll shut it. Go. Quickly.’

Jean turned round just long enough to shout: ‘I told you two to stay here.’

‘Go quickly. Don’t worry about us.’

CHAPTER 2

Jean had just taken a corner too fast. The back wheel of the bike had skidded violently but he had rediscovered a reflex from the time when he was riding in small regional races – all his weight on the outside pedal – the right – and his left leg bent, his foot halfway off the pedal ready to make contact with the road to start a rapid headlong gallop before the inevitable tumble. However everything was brought under control, and already, through the leaves of the chestnut trees, Jean could make out the weathervane on the church. He took a deep breath and hurried on, head down. He was going to find the lot of them, knock back a drink, return home in triumph, and get back to work. There were six hay carts to load and unload. Three for Gaston, three for Francis. Payback! They’ll see!

He slammed on both brakes at once. The front one was better than the back, less worn. The wheels gripped the gravel which jingled musically in the spokes before rattling to the ground. The bike ended up sideways across the road. Jean jumped off, stumbled and only just kept his balance.

Face-to-face with a machine gun, he blinked. He did his best to feign alarm, because deep down it came as no surprise to him. When he left the farm he had abandoned any possibility of being surprised. Given what he could see, he came to the gloomy realisation that the road was completely blocked by a German light tank and a lorry, the one he had almost crashed into. Some cars were parked on the verges. A little closer to the lorry a line of men and women stood in single file motionless in a dusty ditch, a fixed and empty look on their faces. They all created an impression of great calm as if, at the moment they became aware of their powerlessness, they had totally removed themselves from the world.

Jean stepped forward.

‘Halt,’ shouted the man with the machine gun, a massive bloke with red cheeks and an oddly vague and sleepy air to him.

Jean was expecting this. But he was ready to do anything to avoid joining that line of people with that look of frightful patience about them.

‘I have to get through,’ he said calmly.

The German shook his head and Jean noticed then that he was smiling. This smile made him seem very young, cheerful and easy-going. Mr happy-go-lucky! Jean was sure that, wherever or whenever, he could get what he wanted out of a man like this.

‘I’ve got to get through,’ he repeated. ‘My family’s in there. Almost all of them – my wife, my son, my brother …’

Once again the German shook his head. His smile became even more cheerful, but his finger stiffened on the safety catch of his machine gun.

At that moment, another German, an officer for sure, came up and said a few words. The smile disappeared from the soldier’s face. He saluted and stepped back a few paces.

‘What do you want?’ the officer asked.

‘To get through,’ Jean said.

‘You are not allowed through, Monsieur. Do you live in Verrièges?’

This one was not smiling. On the contrary, he looked extremely serious. However, there was no hostility in his look. He had fine features and spoke French without an accent, almost perfectly, with maybe just a little too much effort.

‘No,’ said Jean who was feeling at ease. ‘I live a couple of kilometres from here. But my family …’

The officer interrupted him, without rudeness and with a sort of urgency which seemed well-meaning.

‘Yes, I know. I heard. But there’s no point insisting. Your papers please.’

Jean took a ration book and old hunting licence out of his pocket. The German gave them back immediately.

‘Good. Now, on your way, and tell yourself you’ve been lucky.’

‘Lucky,’ Jean repeated, astonished.

‘Yes. That you don’t live in Verrièges.’

A glimmer passed over the man’s clear face and Jean no longer found his expression reassuring. The other one’s brutish mug was less worrying than this crystal-clear expression, as clear as the surface of water reflecting unknown stars.

Once again Jean felt the sweat turn cold on his brow and in his armpits. He already knew he would not get permission to go through.

Besides, the German officer had turned away and headed off.

Among those lined up in the ditch was M. Chabaud, the watchmaker from Donzac. Jean barely knew him. Even so he automatically went towards him. Where was he to go now he couldn’t get through? Here or elsewhere, what did it matter?

The watchmaker called to him, in an almost hateful voice.

‘Are you off your head? Get out of here quick! The officer who was here before that one, he began by shoving everybody in the ditch. Then he sent anybody from the commune off to Verrièges. He wouldn’t have let you off the hook.’

The moustachioed face of this little man struck Jean as horrible. How come he hadn’t noticed before that M. Chabaud had the face of an evil maniac? Wouldn’t have let you off the hook …? What hook, eh? What did he mean? What was he implying?

‘You shouldn’t believe everything you’re told, M. Chabaud,’ said Jean impatiently. ‘What do you suppose they’ll do with the people from Verrièges? They can’t arrest everybody.’

The watchmaker shook his head.

‘No, they can’t arrest everybody. And I don’t know what they want. Nonetheless, if I were you I’d have taken off by now … it’s not as if by lining up with us here you’ll be doing anything for those on the other side.’

This time the little moustachioed man was making a good point. First of all, don’t get nabbed. There were other ways into Verrièges. The Germans couldn’t know all of them.

‘Goodbye, Monsieur Chabaud. Thank you.’

CHAPTER 3

Jean left the main road and spent a long time cycling around the side roads, where the dried mud formed whitening crusts, then along the paths so narrow that the twigs whipped his face and scraped against his cotton trousers. A hundred metres out from Verrièges, he abandoned his bike and began to crawl the length of a hazel hedge through the tall grass that Peyraud, the tailor, had not yet cut. He had to cross a sunken lane and make it to the edge of a stream where the thick willows would provide cover as far as the first houses of the town. This was the only tricky moment in an otherwise perfectly calculated route.

The path was no more that a couple of metres wide. Jean was about to cross it in a single bound when the throbbing sound of a motor approached at high speed. Hidden in his hazel bush, Jean saw a motorcyclist go past an arms-length away. He was wearing camouflage, dirty green with splashes of brown and grey.

This was the moment …

He jumped across the lane, grabbed onto the bank then gripped the undergrowth of the hedge. The hole he had spotted was right there. He had already found his balance among the hazel branches and was about to jump, when a man on the other side of the hedge rushed at him head down and knocked him backwards.

Jean had managed to hold on to a branch of the hazel tree. The man who had shoved him back took hold of his sleeve and gave him a warning: ‘Don’t stay here. They’re after me.’

A machine gun opened up and they heard above their heads the furtive rustle of bullets through the leaves. Once back across the lane, they tumbled quickly down the slope that Jean had so carefully climbed without disturbing the long grass that had hidden him. As he leapt across a deep hole that he thought was narrower, Jean stumbled. His companion fell on top of him with all his weight. They rolled over and over until Jean’s shoulder smashed into a stump.

He felt such intense pain he thought he was going to faint. Not now! The motorcyclist could be coming round the corner of the meadow. Jean took off running again. With each stride he felt like he would dislocate his shoulder, but he kept on running. A couple of times, he heard – or thought he heard – a burst of machine-gun fire. He ran even faster.

His companion always managed to stay within a few metres of him, although he was only short. When they found some cover, Jean took a moment to look at him and recognised him immediately. It was Daniel Graetz, the Jewish lad from Lorraine who worked over at the Pradet’s farm.

As soon as he stopped, his shoulder hurt so bad he had to lean with his back against a tree.

‘Have you been hit?’ asked Graetz.

‘No. It was in the meadow just now. I smacked into the stump of a poplar. I even knew it was there – that bloody old fishpond. It’s nothing. It’ll wear off.’

Daniel Graetz was breathing heavily and a fleck of foam was forming at the corners of his mouth. His eyes shone like those of a hunted animal.

‘How did you manage to slip through their fingers?’ he asked.

Jean liked this tone of complicity. It reduced his anxiety for a moment. He had a sense that he was solidly in the world, free and light, and that he had let slip an intolerable burden from his shoulders. The relief was such that for a moment he remained silent, wondering if he was going to let Daniel believe that he had in fact just escaped. But lying was not his strong point; already the weight of other lives pressed down on him, lives which counted for more than his own, of which his own was no more than a reflection.

‘No,’ he said. ‘I haven’t come from Verrièges. I wanted to get there. All my family’s there.’

The boy’s bewilderment stirred no emotion in him. He had expected it. He now understood that his long journey had been worse than useless. He had wasted his time. He should have … what? He didn’t know what he should have done. What was little Graetz saying?

‘… my father’s there, and my cousin too. But they won’t take the old man far: sixty seven and crippled with rheumatism. And Armand, my cousin, has got one leg in plaster. They’ll stick them in a camp. But I’ll be more use to them at large than if I let myself be sent off to the salt mines, or worse …’

Jean looked in Daniel’s direction but could not see him. He’s right, he thought. What he says is sensible. I’m the one who’s not being sensible. I’ve behaved like a crazy kid.

Daniel Graetz had already said goodbye and was moving off among the trees with long, supple strides, his elbows by his side.

Jean went off in search of his bike.

CHAPTER 4

After he had exchanged a few words with the tall, thin peasant with unsettling eyes (a clumsy hand had penned ‘Bricaud Jean’ in his ration book), Colonel Wolfgang Rehm had himself driven back to the Place du champ de foire in Verrièges, the spot he had chosen to assemble the populace.

This ‘Jean’ had the very look and bearing of a fierce resistance fighter in the maquis. Napoleon, during his disastrous expedition to Spain, must have come across such men; gaunt but ferocious, tireless, scornful of the rules of war, dangerous even to their dying breath.

When talking to him, Rehm had had a moment of hope. With an adversary such as this, his mission might take on some meaning.

For Jean was more than an adversary: he was a true enemy. Against him, against men like him, the war reverted to its original meaning and became a vital function: destroy or be destroyed.