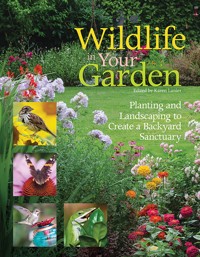

Wildlife in Your Garden E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: CompanionHouse Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Imagine a thriving garden in your backyard, bursting with vibrantly colored blooms and lush green leaves, shaded by tall trees. Now imagine the same garden, alive with buzzing and flapping and chirping and croaking. Imagine the ecological impact of encouraging natural pollinators. Imagine the excitement of watching your garden become a hub of activity and learning about all of its different visitors. For those who relish observing nature in action, planning a garden to attract certain types of wildlife can bring daily enjoyment right into the backyard. Inside Wildlife in Your Garden: How to deal with and even appreciate the insects in your garden Reptile and amphibian backyard visitors and how they can contribute to a healthy ecosystem "Birdscaping"—planning and planting with birds in mind A special section on hummingbirds that includes an illustrated guide to twelve common types Using binoculars and field guides to identify birds by sight and by calls Different types of pollination and the plants and food crops that depend on it Butterfly metamorphosis and gardening for the different life stages How bats and moths take over pollination duties at night Learning to coexist with four-legged furry friends who like to dig and forage Natural ways to protect your garden from pests and discourage harmful wildlife

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 423

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Wildlife in Your Garden

Project Team

Editor: Amy Deputato

Copy Editor: Joann Woy

Design: Mary Ann Kahn

Index: Elizabeth Walker

LUMINA MEDIA™

Chairman: David Fry

Chief Executive Officer: Keith Walter

Chief Financial Officer: David Katzoff

Chief Digital Officer: Jennifer Black-Glover

Vice President Marketing & PR: Cameron Triebwasser

Managing Director, Books: Christopher Reggio

Art Director, Books: Mary Ann Kahn

Senior Editor, Books: Amy Deputato

Production Director: Laurie Panaggio

Production Manager: Jessica Jaensch

Copyright © 2016 Lumina Media, LLC™

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Lumina Media™, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

eBook ISBN 978-1-62008-257-7

This book has been published with the intent to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter within. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the author and publisher expressly disclaim any responsibility for any errors, omissions, or adverse effects arising from the use or application of the information contained herein.

2030 Main Street, Suite 1400

Irvine, CA 92614

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to help you reconnect with your wild side and the green space just outside your door by discovering the importance of the patch of earth that you tend and the creatures who find sustenance there. We have taken the wilderness out of most places where humans live, and now we are wondering why we feel unhealthy; why our air, food, and water is polluted; and why stress permeates modern lifestyles. Biophilia, the general tendency that humans have toward connecting with other forms of life, must be nurtured for our common good, and finding our place in relation to wild creatures is one way to restore ourselves.

How do we return our landscapes to being working systems that filter water and air? How do we grow food without pesticides? How do we encourage native wildlife to reestablish healthy populations? How do we prevent other wildlife from becoming a problem?

Although all of these questions may not be answered completely in this book, I hope that you find within its pages a starting point to coexisting with wildlife in your garden. I hope your approach becomes one of curiosity, respect, appreciation, awe, and understanding. If you have a garden, a yard, a community space, or an office with landscaping, a range of wildlife can become part of your daily routine, and this book will help you recognize those animals that you’d like to get to know better.

This book provides opportunities for understanding by exploring histories of selected animals, what they do, and why; animals’ role in the ecosystem and their impact on your garden, home, neighborhood, community, and watershed; and the impact we have on animals and how we can encourage or discourage their presence. Each section will familiarize you with wildlife, ranging from abundant soil organisms all the way up to the largest and rarest mammals that may share your space. I encourage you, at any of these encounters, to first simply observe. What exactly is that moth, bird, squirrel, wasp, mouse, raccoon, or opossum doing? Try not to react to its presence—just watch. Does it visit flowers or gather seeds? How many different types of plants does it visit? Do you see it at night or in the morning? Does it show up reliably all year or just in certain seasons? Where does it take the food it gathers?

This act of slowing down and just looking at a subject is a technique employed by artists, hunters, biologists, and philosophers. The less threatening your presence is to wildlife, the more familiar you can become with the animals’ normal routines, and the more details you will notice. It is very important that we don’t disturb wildlife unnecessarily, especially during times of low resources, such as a long, hot summers or when they are storing up energy for the winter. This is a lesson for us to share with our children as well as teach to ourselves. Respecting space and similar ethical principles are important in your yard. Know why you are taking action before you do something, and consider the other living creatures that you will affect.

Permaculture (shortened from “permanent agriculture”) is a holistic landscape design philosophy that holds a basic tenet of working with nature, not against it. Rather than seeing your yard as a perfect utopia—or as a battleground, where it’s man versus nature—I like to think of gardening as a partnership with wildlife. We provide them habitat, and they do the work: pollinating flowers, planting seeds, turning soil, keeping populations in check, and breaking down and recycling nutrients. Rather than seeing ourselves as overlords of the land, we can be cooperative participants with the native residents.

I prefer not to label any wildlife as “good guys” or “bad guys” in this book; instead, I strive to provide basic information on what animals need and how they live. You can decide which ones to invite to dinner. I ask you not to think of your property as a space where you have the right to kill what you think does not belong. Do think of your garden as a wildlife refuge, where learning and understanding are your most powerful tools.

The information provided in this book may work well for the home gardener who can tolerate plant losses for a few seasons while his or her efforts to bring a natural balance to the garden play out. I also hope that gardeners and landowners consider the ideas and alternative solutions on a wider scale. Many resources exist for targeting those wild animals regarded as nuisances or invasive, and although I address some of these in their respective sections, you will also be able to access experts in your area. Alternatives exist for every problem, and looking at the reasons behind the issue often reveals the solution. With this approach, we can enjoy our sanctuary with wildlife rather than a creating a barrier that separates the two.

As Douglas Tallamy, author of the essential native plant landscaping book Bringing Nature Home points out, if we all work together to increase the biodiversity in our own yards, North American suburbia could improve on the protected public lands, such as national parks. At this time, 92 percent of suburban landscape is lawn. This holds great potential for renewing our connection with nature and giving wild things what they need to survive. Our yards could become the largest corridor of connected natural habitats in the developed world. It only requires some small modifications in our attitudes and our landscaping. You don’t have to be big to make a difference in the world—if you need proof, just watch the insects.

1

Your Garden

The basic steps in creating a garden that provides a safe habitat for wildlife and functions to improve the environment are:

1. Stop using pesticides.2. Replace nonnative lawn turf with native plants.3. Watch and enjoy.Sound too easy? OK—I’m oversimplifying matters. You can delve as deep as you want to with Step 2, which can be a process that extends over more than your lifetime. Consider who will be tending the land after you are gone and what kind of legacy you will leave. Have a vision in mind, choose a starting point, and adjust as you go. Use the following concepts to check in with yourself and your garden periodically.

What do the natural areas in your locale look like?

Make Observations

Before you set out to create a backyard wildlife sanctuary, make sure that you understand your local ecology. Find out what the native ecosystem was like before the area was developed. Go to your closest natural areas and spend time simply observing, preferably in all types of weather and all seasons. Take a notebook along and record your observations about the height of the tallest plants, the wildlife you see in each layer, the amount of water and whether it is flowing or still, which plants and animals seem to be thriving, and what might be missing from the landscape.

Talk with naturalists about native wildlife and what they have done to restore the habitats at their sites. Once you start these types of conversations, you’ll notice that your observation skills will be sharper every time you see landscapes. As Marlene Condon observes in her Nature-Friendly Garden book, “The natural world does nothing that is nonsensical.” You can take home some of the best ideas and try them out for yourself.

Echinacea, or purple coneflower, is a top pick for Midwestern gardens.

Work with Natives

In nature, nothing exists in a vacuum. Communities, or guilds, of plants grow together because of mutually beneficial relationships, coevolution, and the right growing conditions. In Gaia’s Garden, Toby Hemenway summarizes what wild nature does best, and we can try to emulate this in our gardens. “A healthy plant community recycles its own waste back into nutrients, resists disease, controls pests, harvests and conserves water, attracts insects and other animals to do its bidding, and hums along happily as it performs these and a hundred other tasks.” So that’s our goal. Native plants offer many advantages toward achieving this state.

In Rick Darke and Douglas Tallamy’s book The Living Landscape, a native species is defined as “a plant or animal that has evolved in a given place over a period of time sufficient to develop complex and essential relationships with the physical environment and other organisms in a given ecological community.” Some gardeners like to simplify matters by defining native plants as those that have been in the region since before Europeans arrived on this continent. Native plants generally, but not always, require less maintenance and care than exotic or ornamental species. They don’t necessarily stay where you plant them, and they can become even more vigorous than you expected. Natives call for you to be adaptable because you can try to assert your will over them, but they may surprise you. As Darke and Tallamy put it, “Managed wildness and an invitational approach to chance happenings can sometimes accomplish things that would be impossible through more deliberate methods.”

Intimate relationships between native plants, insects, birds, and other wildlife have evolved cooperatively over millennia. We need to keep an open mind and appreciate that the partnerships that this type of history cultivates are far more complex than the ones that we gardeners might develop with our plants. A few good reasons to select native plants are that they generally have deeper roots and prevent excessive runoff during heavy rains. They help filter and slow down stormwater. They provide essential sustenance to migratory species, such as the monarch butterfly. Also, compared to lawns, they absorb a great deal more carbon from the atmosphere, helping to reduce greenhouse gases.

1. Like a healthy forest, your garden should include multiple layers. 2. Trillium is a spring-blooming plant native to the northeastern United States.

Landscape in Layers

Forest gardening, one aspect of permaculture, promotes establishing several vertical layers of plant communities that form naturally in a healthy forest ecosystem. Your home ecosystem may be prairie or desert, so take that into consideration and adapt the layers to match your area’s climate. The following basic outline can be applied to most regions.

The tallest forest garden layer is the canopy. These are the dominant trees, the “roof” of the garden. The trees’ crowns are the first to catch and store sunlight, filter air, and recycle oxygen and carbon dioxide. The size and conditions of these big beauties affects all the life underneath; likewise, they reflect the state of affairs going on far below the ground surface.

The layer below the canopy is the understory. This includes younger canopy trees and shorter growing tree species. They compete for light and adapt to maximize the efficiency of their leaves in capturing the sun’s rays. Some leaf out before the canopy trees in the spring, and some have modified the anatomy of their leaves to function on lower light levels. This is where a graceful transition in design can be made from the towering canopy down to human-scale features.

The middle layer of life is the shrub layer. Shrubs and bushes are usually woody, multistemmed plants up to a height of around 15–20 feet. This layer can be a prime shelter for wildlife: a hiding spot midway between the safety of a high nest and the open foraging space on the ground. Berries, nuts, flowers, and foliage all provide something attractive, and a healthy shrub layer will encourage a diverse assortment of wildlife.

The herbaceous layer varies in plant height, with grasses and forbs (flowers and herbs) stretching up to several feet high or creeping low. The diversity of species increases as we move lower down in the forest garden layers, and although the individual plants consist of less mass, they are relatively more productive in their role of supplying food and returning nutrients into the soil. The herbaceous layer is where most of the interesting and colorful blooming plants take turns sharing their colors, fragrances, and textures throughout the seasons.

1. Vines add a decorative touch while benefiting other layers of the garden. 2. Swamp milkweed is popular with monarch butterflies. 3. A monarch caterpillar feeds on a leaf of swamp milkweed.

A layer that can touch all forest garden layers is the vine layer. Vines take up very little space and provide little surprises of color, seeds, and fruit throughout the shrub, understory, and canopy layers. Vines make productive fence decorations and can create screens for privacy. Be cautious when selecting vines because there are some very invasive types (such as certain commonly planted nonnative varieties of honeysuckle and wisteria) that will take over. Opt for the native varieties so that wildlife will find what they need.

Perhaps the most critical layer for overall garden health lies below our feet: the ground layer. It includes several zones on the surface and below. Ground litter includes all kinds of plant and animal droppings, seeds, twigs, leaves, and dead wood, and it serves many purposes. It provides insect cover and food, retains moisture, and holds microhabitats for fungi, bacteria, and other microbes that break down the litter into soil.

The ground layer contains more life forms than any other layer. On the surface of the soil, you’ll find mosses, algae, salamanders, and beetles, to name a few. Underground, most insects spend at least part of their life cycles in the soil, as do many reptiles and amphibians. As for the impressive “roof” or canopy, it wouldn’t be there without a foundation. The root systems of trees extend out from the trunks at least as far as the canopy branches and reside mainly in the 2- to 3-foot depth, where oxygen is available in the soil. Native grasses and wildflowers may grow deep taproots that plunge 6 feet or more into the earth. A community of mycorrhizal fungi and microbes release organic compounds into the soil that feed the plant roots.

In contrast, mowed turf grass adds very little support to the ecosystem, and the soil compacted by riding mowers makes is almost impermeable to water. Herbicides that kill forbs prevent a biodiverse system from establishing itself, and they set off a cycle of spot treatments for symptoms without addressing the underlying systemic malfunctions.

Likewise, removing nature’s nutrient-rich gift—fallen leaves—takes away the soil-enriching and biodiverse benefits that leaf litter provides. Then we have to go out and buy topsoil, fertilizer, and compost; haul it home; and blend it back in to amend the soil. Douglas Tallamy sums up the wasted effort: “Plants make leaves, and we all freak out and get our leaf blowers and our rakes, we rake up all the leaves and put ‘em in bags and treat ‘em like trash. Then we run to Home Depot and buy mulch, fertilizer, hoses, trying to replace the ecosystem services we just threw out, but we can’t replace the arthropods we got rid of.” If we can let leaves stay where they fall or chop them up with a lawn mower and rake them to cover our garden beds, we’ll be on our way to sharing the gardening work with Mother Nature instead of doing all of the work ourselves.

Zinnias add a splash of color and plentiful nectar to your garden.

Switchgrass is a native grass that can grow several feet high.

The ground layer nurtures both plant and animal life.

Understand the Food Web

You’ll read about birdscaping and gardening for beneficial insects later in this book, but keep in mind that you cannot really garden for a particular type of wildlife exclusively. As Marlene Condon explains in Nature-Friendly Garden, “When you grow nectar plants for butterflies and hummingbirds, you will also attract moths, wasps, bees, and many other kinds of insects.” Spiders and caterpillars will feed on them, and they will attract birds. Maybe even deer will join the party. Condon goes on to assert, “You need to accept that all of these creatures are part of your world and include them in your garden planning.” This is our garden’s food web.

We all know the concept of “the big fish eat the little fish.” What do the little fish eat? Algae, plankton, insects. What do insects eat? Start with any food or animal, follow this thread to its source, and eventually you wind up at plants and, ultimately, the sun. Practically all life on Earth depends on the sun’s energy, which is captured by leaves and photosynthesized. An animal eats the plant and absorbs energy, which is transferred to the next animal and so on. This is a food chain.

Every food chain consists of producers, consumers, and decomposers. Plants are the main producers. Consumers are generally categorized as herbivores (plant eaters), carnivores (meat eaters), and omnivores (both plant and animal eaters). Decomposers help break down the nutrients and minerals and recycle them back into the system, which makes the system not such a straight line. There could be many food chains that interrupt or interconnect with each other. The term food web describes the various interweaving parts of food chains.

As with a spider’s web, if one strand is broken, many others remain in place and do the same job. In permaculture, this is referred to as redundancy—the concept that multiple elements provide the same function. Redundancy puts less stress on any single member of the system, which is why more biodiversity, or a variety of life forms, helps increase a system’s stability and resiliency. Lose one? No big deal. Another will fill in until balance is restored. A monoculture, on the other hand, which features a single predominant species, is more vulnerable to disease or predation. For example, many housing subdivisions are planted with one type of street tree. If you lose one, you might lose them all.

In Peter Bane’s Permaculture Handbook, he compares our knowledge of our plant ecosystem with that of our ancestors. “The average Cherokee woman at the time of European contact knew and used approximately 800 species of plants for food, fiber, and medicine.” Most vegetable gardeners today would be doing well to have thirty to fifty species growing, and, in a permaculture garden, that number could be multiplied by ten. Commercial, governmental, and industrial growers are not necessarily concerned about the heritage that they lose by decreasing plant diversity. It is up to the small-scale growers to preserve the native plants and heirloom fruits and vegetables and keep trying new ways to diversify the garden.

Know that Your Garden Matters

Douglas Tallamy, in Bringing Nature Home, explains why every plant decision you make is important. “Because food for all animals starts with the energy harnessed by plants, the plants we grow in our gardens have the critical role of sustaining, directly or indirectly, all of the animals with which we share our living spaces. The degree to which the plants in our gardens succeed in this regard will determine the diversity and numbers of wildlife that can survive in managed landscapes. And because it is we who decide what plants will grow in our gardens, the responsibility for our nation’s biodiversity lies largely with us.”

Bee balm (Monarda spp.) attracts bees, butterflies, and birds with its nectar.

Your property, with the ecosystem services it provides, is your place to make a difference in the world. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines ecosystem services as “the multitude of benefits that nature provides to society.” The ecosystem comprises all living and nonliving parts of the environment and their interactions that benefit the world. Those essential services and benefits include cleaning the air, purifying water, providing spiritual connections, pollinating, stabilizing and forming soil, and providing recreation. The FAO estimates that all of this collectively adds up, worldwide, to a value of $125 trillion; however, “these assets are not adequately accounted for in political and economic policy, which means there is insufficient investment in their protection and management.”

Tallamy and Darke delve further into the role of the garden in the larger environment in their book The Living Landscape. Ecosystem services that your very own garden can contribute to include:

• supporting human populations• protecting watersheds• cooling and cleaning air• building and stabilizing topsoil• moderating extreme weather• sequestering carbon• protecting biodiversity• supporting pollinator communities• connecting viable habitatsMay you find inspiration in the good you are doing in your own little corner of the world.

A honeybee on an apple blossom. Honeybees are important to apple pollination.

Worms help gardeners in many ways, among them aerating the soil and producing nutrient-rich castings (waste).

Soil Matters

Originally printed in the April 2015 newsletter for the Lexington, Kentucky, chapter of Wild Ones: Native Plants, Natural Landscapes

Why care about the soil? Because soil is alive! Soil is the most biodiverse part of your garden ecosystem. Millions of organisms can inhabit a spoonful of rich, healthy soil. Every arthropod, bacteria, fungus, or worm plays a role that affects the other members of the soil community. They shred, graze, parasitize, and predate on each other, but they mainly take care of organic matter. Underground organisms process everything from leafy tendrils to tough tree trunks; they also build the infrastructure for plants’ roots. They make nutrients available, disperse water, and open air pathways for good circulation, creating a healthy community or habitat.

The benefits of biodiversity in your soil don’t stop with the plants. Recent scientific studies support the hygiene hypothesis, which theorizes that people who grow up in developed countries are too clean for their own good. Researchers are finding that early exposure to healthy amounts of bacteria, fungus, and even some parasites could build children’s immune systems, leading to fewer inflammatory conditions as adults. Scientists are trying to identify which members of a healthy gut microbiome affect specific problems, ranging from Crohn’s disease to autism.

Similarly, soil scientists are often interested in isolating the bacteria and fungi that create certain changes in soil chemistry and fertility. However, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) states, “Many effects of soil organisms are a result of the interactions among organisms, rather than the actions of individual species. This implies that managing for a healthy food web is not primarily a matter of inoculating with key species, but of creating the right environmental conditions to support a diverse community of species.”

Where do you find the richest, most diverse, and most resilient soil systems? In forests. Forests can have up to 40 miles of fungus in just one teaspoon of soil, compared to several yards of fungus in a teaspoon of typical agricultural soil. Gardening with native plants and natural systems encourages a rich, biodiverse community above and below ground and mimics the conditions found in the wild forest. So go ahead and get some of that good dirt—er, soil—under your nails.

The soil in a healthy forest supports a thriving, biodiverse community.

2

Insects: A Respectful Approach

The majority of gardening approaches portray bugs as the bad guys and easy-application pesticides as the answer to wiping out your woes. Sure, you can have a picture-perfect garden if you kill everything that might ever disrupt it. But that’s no way to live and let live. The same synthetic methods used to control “pests” also bring a whole host of side effects: everything from collapsed colonies of honeybees to weak-shelled eggs in eagles’ nests to many types of cancer in humans. Another alternative is to allow a little be-wilder-ment into your heart, and let it find a place in your yard as well. Do you have to love bugs and spiders to have a wildlife-friendly yard? Love is not required, but tolerance is.

Consider this insight from Nelson Mandela: “If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. Then he becomes your partner.” Many bugs, creepy-crawlies, and slimy slitherers can be your garden partners, if you allow them to be.

Instead of listing every type of garden pest and the havoc they wreak, this section introduces some beneficial bugs. In nature, there is no such thing as “good guys” and “bad guys.” Every creature—yes, even spiders, slugs, and ticks—exists for a reason, whether we understand their role or not. You may be surprised at how many commonly squished, swatted, or shunned insects are hard at work to keep your garden ecosystem in balance.

Aphids can suck the life out of plants, but they are a major food source for beneficial garden bugs.

I like Jessica Walliser’s definition of an ecosystem in her book Attracting Beneficial Bugs to Your Garden. “An ecosystem, in essence, is a community of organisms functioning hand in hand with their environment and each other to exchange energy and create a nutritional cycle. Insects are innately connected to each and every activity occurring in the ecosystem of your garden.”

It would be an oversimplification to call every creature covered in this section an insect or a bug, but since the average gardener does not describe a spider as an arachnid or a slug as a mollusk, I’ll use the easiest terminology and lump them into the same category. Even including soil life is stretching the taxonomic boundaries if we want to acknowledge the fungus and mycorrhiza that make plant life possible below ground.

I’ll admit that this does a disservice to the immense diversity within this group. Insects and arachnids comprise a whopping 80 percent of the world’s animal species. They are everywhere, whether shockingly visible, mysteriously camouflaged, or microscopically minute.

The forest floor allows mosses, fungi, and, of course, insects, to thrive.

Layers of Insect Life

Insects may be the least understood or appreciated type of wildlife, but they are by far the most abundant. Deserts, mountains, prairies, and forests alike harbor more six- and eight-legged creatures than reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals combined. It’s not easy to estimate, but entomologists write in the textbook Entomology and Pest Management that there are 400 million insects per acre.

Why not try and count them for yourself? When you step into your garden or yard, try surveying all of the habitats that are supporting insect life on all levels and during all life cycle phases. Try to lie, squat, kneel, and stand in just one spot as you take an inventory of the signs of wildlife at each of these levels.

Start as low as you can go. Important work is going on at ground level and below. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), there are more microorganisms in just one teaspoon of healthy soil than there are people on Earth! They are busily working through the leaf litter and animal remains, transporting and transforming nutrients. Springtails, beetles, mites, earthworms, and ants devour each other, deposit rich castings, lay eggs, and tunnel throughout the soil. Their normal life processes turn, aerate, and circulate humus without even the slightest hint of a spade or garden fork. Too small to see without a microscope, microbes such as bacteria, fungi, algae, yeast, nematodes, and protozoa process organic matter into forms that plants’ roots can absorb.

Work up to the herbaceous layer, where flowers bloom and grasses sway, and look for some of the same soil creatures above ground. Beetles, roly-polies, leaf hoppers, lightning bug larvae, aphids, ladybugs, and slugs are a few of the crawling varieties. Many of these devour the others, while some simply scavenge the leftovers and make a fine life in the protective ground-cover plants. The winged creatures—bees and butterflies in the daytime and moths by night—are busy about the flowers, sipping nectar and gathering strength while they relocate pollen from one plant to the next.

Continue up into the shrubs that harbor our beloved songbirds. Caterpillars find the leaves delectable, and baby birds think the same about the soft, squishy caterpillars, which nature places within easy reach of nests. As if that weren’t enough, more predators come along to feast: parasitoid wasps lay their eggs, predatory stink bugs attack with hidden weapons, and spiders trail their deadly decorations across flight pathways.

Head on up into the understory trees, where you’ll find more flowers, fruits, and nuts. Winged insects pollinate, and cicadas reach their height of song season. Mantids await their prey patiently or catch a swift breeze to try another hunting stakeout.

Stretch up into the big shade trees that create our cooling canopy. Katydids resonate with the twilight, bark beetles burrow and evade drilling woodpeckers, and webworms cast their community hammocks across the crotches of branches.

To highlight the importance of insects in our gardens and in our lives as a whole, they are grouped according to the service they perform in the ecosystem. Sally Jean Cunningham’s book, Great Garden Companions, points out some important, even critical, services that we humans really aren’t too good at providing, such as pollinating, recycling resources, and maintaining a balanced food web. Think about it! How well can you pollinate every flower in your garden by hand? Are you able to chop up or chemically digest every dead animal and plant on your property so that the nutrients are released back in the right proportions to form rich, fertile soil? How about manipulating the intricate balance of nature’s food web by providing the right amounts of the right nutrition at the right time for the wildlife that you want to attract? What if you overdo it? Can you then consume or destroy the right amounts of the overgrown populations so that everything is balanced again?

1. A juicy caterpillar on a leaf will be a lucky bird’s next meal. 2. Cicadas are more often heard than seen from up high in tree branches. 3. Did you know that the daddy longlegs is not a spider? It is, however, a major player in your garden ecosystem.

It sounds like a full-time job for an army, and that’s what you are blessed with—an army of ecosystem service providers, especially when you plant native plants and landscape with natural processes in mind. Major players (and a few unsung heroes) are described in this chapter according to the main job descriptions that bugs are born to fill:

• Pollination:Flying and crawling insects that specialize in spreading genetic material among blossoms to fertilize and increase biodiversity. These include bees, butterflies, moths, wasps, flies, and beetles.• Population control: Predators and parasitoids that help normalize numbers of prey species over time (and predators can become someone else’s prey, too!). These include spiders, assassin bugs, dragonflies, and lacewings.• Recycling: Scavengers and decomposers that break down dead and decaying plant matter and carrion and turn it into useful components in the soil. These include worms, centipedes, daddy longlegs, and sow bugs.Please note that some insects perform all three of these jobs; many are multitaskers! And all insects provide a food source to other creatures. Birds, lizards, frogs, fish, coyote, bears, and even people either eat insects or eat something that has eaten insects.

Pollinators

Who loves flowers more than you do? Pollinators! Gardeners have a lot in common with pollinators: we are attracted to the scent, color, and shape of flowers, and we survive by eating the food that flowers provide. For pollinators, it’s the nectar, and for us, it’s the fruit that develops after the plant is fertilized.

Types of Pollinators

Animal pollinators discussed in this section on insects and arachnids include bees, butterflies, moths, flies, wasps, and beetles. We’ll discuss birds and bats later, in separate chapters of the book. Regardless, the general job description is the same for all pollinators: they visit flowers, looking for food, nectar, and pollen, and they inadvertently spread pollen to the reproductive organs of other plants, thereby fertilizing them and allowing them to reproduce through the development of seeds and fruit. Plant sex really is all about the birds and the bees!

Animal pollinators often are winged creatures designed to travel distances quickly and efficiently, helping nature spread plants’ genetic material beyond the small area of your garden bed. But not all pollinators are live animals. Wind and water also spread pollen from one plant to another, ensuring that genes have the opportunity to make more varieties with different traits—in other words, increasing biodiversity.

Pollination Syndromes

Pollinators are fascinating to watch and, as you pay closer attention to their habits, you may discover their preferences. How does a flower attract a pollinator, and how does a pollinator pick a flower to visit? Like a key that fits a lock, the flowering plant has coevolved with its vector, or type of pollinator. These traits that attract a certain type of pollinator are called pollination syndromes; some are obvious, while others are a bit more mysterious.

Colors are probably the most obvious attractive quality of flowers, and hummingbirds certainly fixate on anything red. Colors also attract butterflies, and it is the sight of a milkweed in bloom that draws in a migrating monarch to dine on its juice. Butterflies prefer flower shapes that facilitate their landing, so upturned blossoms with sturdy petals, such as coneflowers, are a win.

Wasps are often underappreciated for their pollinating ability.

As much as bright colors mean food to butterflies and birds, the opposite is true for night-flying insects and bats. The flowers they visit are pale, usually white or dull shades of pink and green. Moths are drawn in by their keen sense of smell, and they find their dinner in the depths of strongly sweet tobacco flowers and Easter lilies. The fruit bats of tropical climates sniff out the musty odors of banana and agave in bloom.

What are flies attracted to? The smells that we are not attracted to, such as rotting meat. Not all flowers smell sweet and look pretty. Flowers that lure in flies, such as skunk cabbage or philodendron, have a putrid odor. Beetle-pollinated plants might not have an odor at all, or they may be strongly fruity or fetid smelling.

Birds generally have a weak sense of smell, although all pollinators have varying abilities to detect wavelengths of light beyond the color spectrum visible to humans. Patterns, colors, and designs convey secret messages to their intended audiences. For example, the human eye has three color receptors—red, green, and blue—whereas birds have four color receptors and can see a greater degree of complexity. Some birds are equipped to see violet, and others can even see ultraviolet (UV) light.

1. The coneflower’s shape and ample head allow for safe landings. 2. Rosemary is among the plants whose flowers guide pollinators to the source of nectar.

Bees’ visible spectrum ranges from yellow through UV, but not the orange and red wavelengths. Certain flowers, such as penstemon and rosemary, display nectar guides, which could be compared to runway lights to guide pollinators straight into their sweet destination. Sometimes the nectar guides are visible to us, and sometimes they are masked in the UV wavelength.

Flower shape plays an important role in matching up with the right pollinator. Beetle-pollinated flowers, such as magnolias and dogwoods, are open and dish-like. Butterflies and hummingbirds can reach into tubular, trumpet-shaped blossoms in which nectar is concealed but accessible by using a long proboscis or tongue, and they dust the reproductive organs along the way. Wind-pollinated flowers have done away with showy flowers or even petals. Plants such as grasses and walnut trees must have their anthers (male reproductive structures) and stigmas (female reproductive structures) exposed to the air, letting go of pollen at the slightest breeze.

Bees: Buzzing with Life—By Amy Grisak

A healthy garden is alive with sounds—one of the most important being the gentle buzz of the myriad bees pollinating our fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals. A garden without these hard-working characters offers decreased pollination and becomes a source of frustration.

It’s evident when bees are not in the garden. Squash and other cucurbits—pumpkins, cucumbers, melons, and the like—often start to produce, only to have the immature fruit shrivel and die. Other plants produce less.

Pollination by the Numbers

• 250,000 species of flowering plants on Earth• 200,000 species of animals that pollinate• 1,500 species of birds and mammals that pollinate• 100–200 types of domesticated food crops in the United States15 percent of these are pollinated by domestic bees

80 percent of these are pollinated by wild bees and wildlife

• $10 billion worth of crops pollinated by honeybees in the United States• $13.3 billion annual losses due to honeybee poisoning with pesticides• 42 species of pollinators are listed as endangered in the United States3 bats

13 birds

24 butterflies/skippers/moths

1 beetle

1 fly

• 185 species of pollinators are listed as endangered worldwide by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)• 30–75 percent of food and fiber crops depend on pollinators• 15–30 percent of food and beverages that humans consume are fruits, nuts, and seeds produced through pollination• 80,000 hives kept by commercial honeybee producers • 1.3 million colonies of honeybees to pollinate 615,000 acres of almonds in California• 4,000 bee species native to the United States• 700 butterfly species native to the United States• 45 bat species native to the United States• Hundreds of thousands beetle and fly species native to the United StatesSources: Native Pollinators in Agriculture Project and the Xerces Society’s Attracting Native Pollinators

“Eighty-five percent of flowering plants need a pollinator in order to produce,” says Ashley Minnerath, pollinator program administrator for The Xerces Society, a Portland, Oregon-based organization dedicated to the preservation of invertebrate species, including bees and other pollinators. Bees definitely make everything better.

Faced with colony collapse disorder, a devastating phenomenon known to wipe out entire hives with barely a trace, along with threats from pests and pesticides, European honeybees (Apis mellifera) grab most of the headlines. Many other species, however, are capable of ensuring adequate pollination.

The nonnative European honeybee arrived from England to Virginia in the early 1600s with the colonists. Along with honeybees, there are twenty to twenty-five nonnative species in the United States, Minnerath says. The wool carder bee and the horn-face mason bee are two of the more prevalent nonnative species seen in home gardens.

An accidental introduction in the 1960s, the wool carder bee (Anthidium manicatum) from Europe is so named because of the female’s habit of gathering plant hairs (“carding” them, as one does with wool) to create her nest. They’re solitary bees that resemble wasps, with deep-yellow and black markings. Minnerath says that they’re mostly seen on the East and West Coasts.

In contrast, the horn-face mason bee (Osmia cornifrons) was introduced for pollination and then spread, Minnerath says. The species originated in Japan yet resembles our native mason bees and is often used for home pollination, so these bees are dispersed throughout the country.

Although there is a lot of press about the plight of honeybees, many people don’t realize the astounding numbers of resident bees in our yards. Minnerath says that there are nearly 4,000 species of native bees in North America.

1. A hardworking bee pollinates a cucumber flower. 2. Halictus rubicundus, a type of sweat bee, is a pollinator found throughout the United States and Canada. 3. The leafcutter bee was introduced into the United States in the 1920s to revive alfalfa crops. 4. Eastern carpenter bees pollinate through sonication (buzz pollination).

“Some of the native bees are more efficient crop pollinators than the nonnative honeybee,” she says. A 2013 study backs up these claims, looking at forty-one crops worldwide. It found that the native bees were able to set the fruit at twice the rate of the honeybees.

This does not surprise Dave Hunter of Crown Bees in Woodinville, Washington. He’s studied the behavior of pollinators for years and is convinced that encouraging native bee populations can mitigate the severity of honeybee losses throughout the country.

Honeybees are very efficient at what they do, Hunter says. “The honeybee is an industrious workhorse. One bee is a nectar gatherer. One bee is a pollen gatherer,” he adds. Bees that gather the pollen remain very neat and tidy about the whole process, as the pollen goes into the pollen pockets on their back legs. Because of this meticulous nature, pollination is more of an accident than a certainty.

On the other hand, many solitary bees, such as the blue orchard bee (O. lignaria), will practically belly-flop into flowers because they’re there for nectar and pollen. With pollen sticking to the tiny fur on her body, the orchard bee is off to the next flower, which will receive a generous dusting. “Virtually every flower she touches is pollinated,” Hunter notes.

Bumblebees (Bombus sp.), carpenter bees (Xylocopa sp.), and sweat bees (Halectidae sp.) all offer another powerful pollination method. They exhibit what’s called “buzz pollination,” also known as sonication. The bee grasps a flower, and, after disengaging its wings from its flight muscles, it shakes its whole body at a frequency close to a middle C note, causing the release of pollen from the flower.

The most noted plants targeted for buzz pollination are those of the Solanum genus, such as tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants, but it’s also very important for cranberries and blueberries. It’s a fascinating process and one that’s easily observed in the garden, particularly if you can pull up a chair alongside your tomatoes.

It’s also important to understand when during the day various bee species go out to visit the flowers. Mason bees typically fly once the temperatures reach around 50 degrees Fahrenheit, and Minnerath points out that bumblebees will brave cool, rainy weather when honeybees are tucked in their hives.

Knowing that different bees aid in the pollination of the fruits and vegetables—with some species being generalists and others targeting specific plants—it’s wise to encourage all of the pollinators in your area. “A diversity of bees, both the native and European honeybee, can help gardens be more productive,” Minnerath says.

Planting for Bees

Choosing plants with bees in mind remains the first step toward creating a veritable pollinator oasis in your garden. Hunter recommends planting flowers in clumps. “Clumpy stuff will attract more bees,” he says.

Break up the lawn by creating groups of gardens. An ideal situation will have some grass along with groupings of native bushes and plenty of flowering plants.

When choosing varieties specifically for pollinators, try to steer clear of the high-tech hybrids. “Hybrids and double-blossomed flowers are hard for bees to pollinate,” Hunter says. Some varieties are developed for other characteristics, including no pollen in some instances, which also doesn’t benefit bees.

Minnerath recommends native wildflowers, stating that they usually are the best sources of nectar and pollen for native pollinators. “Compared to nonnative plants, native plants are more likely to attract native bees and support a high diversity of butterflies and moths,” she says.

When you look for locally native plants, check first at local nurseries because these plants will be well-acclimated to your region as well as the specific bee populations. For example, when the native golden currants bloom in April and early May in some parts of the country, they provide a valuable resource for newly emerging bumblebees. Willows offer another example of an important early-blooming plant. The native plants for your location are in sync with the native pollinator species.

Minnerath also stresses the importance of providing nectar and pollen sources throughout the seasons. “It is useful to include flowers that bloom early in the spring to provide food for newly emerging bumblebee queens,” she says. “Similarly, it is important to provide flowers that bloom in late summer and fall to support new bumblebee queens for overwintering.”

She recommends having at least three different plants blooming during each season to provide enough diversity to support local pollinators. Of course, more is better. For a visually appealing balance in the garden, it’s absolutely fine if some of these varieties are domesticated flowers. Natives are the best for providing pollinators with what they need, but the winged workers will definitely use other plants, too.

Plants for a Seasonal Buzz

Spring

apples

apricots

cherries

chokecherries

dandelions

grape hyacinth

pears

Pulmonaria

Rhododendron

rockcress

violets

Summer

bee balm

blackberries

Echinacea

Echinops

fireweed

heather

hyssop

Joe Pye weed

lilies

phacelia (called “bees’ friend” because it’s such a strong nectar source)

raspberries

thyme

Fall

barberry

Echium

Sedum

witch hazel

Zinnia

Depending on the severity of your regional weather, late winter and early spring are when the hardy bumblebees emerge from hibernation; other native bees continue to show up as the weather warms. In addition to the willows and currants, Nanking cherries offer early blooms. In the garden, lupine makes a spring appearance in most parts of the country, as do primroses and hellebores.

Later in spring, the garden bursts with variety, and it’s easy to have more than the minimum of three species to accommodate pollinators. Foxglove, columbine, borage, allium, and cranesbill are all spring and early-summer blooming flowers that bring in the bees. During this time of the year, bumblebees and honeybees are out in full force, and more solitary bees emerge. “Mason bees come out when the temperatures are in the 50s [degrees F],” Hunter says.

Penstemons are a stunningly diverse and beautiful collection of well over 200 native and hybrid specimens that typically bloom in spring and early summer—and sometimes in fall if they are cut back during the hottest part of the season. Typically around 2 feet high, the tiny snapdragon-like flowers form dazzling spikes of brilliant blooms. Colors range from the most subtle pinks to hot reds and very close to a true blue. Whatever color you like, it’s probable that you will find it in a Penstemon cultivar. Penstemons are an attractive nectar and pollen source for bees, particularly because the bloom time stretches so long throughout the season.

By the summer, poppies are usually brimming with bees during the cool of the morning, and hollyhocks are similarly crowded. Minnerath recommends milkweed, which is an important forage plant for Monarch butterflies that also makes a beautiful and fragrant addition to the garden with pinkish-purple, ½-inch-wide flowers that cluster into a ball shape.

Sunflowers of all shapes and sizes, including native species found throughout the country, are beacons to bees. The salvias, another sizable group of perennials found throughout the country, offer an important food source. Like the penstemons, they bloom throughout the season and come in an astounding range of colors. Agastache varieties appeal to both bees and gardeners; they are disease- and deer-resistant, providing a good option for planting along the perimeter of the property or in areas where deer browse.

During the summer and often well into the fall, herbs are a boon to bees, too. Minnerath suggests lavender, culinary sage, and basil varieties. When oregano is in bloom, the plant literally buzzes with activity—the only drawback is that when you cut the plant, you’ll need to be extra cautious not to squeeze a bee between your fingers.

Whereas spring and summer are fairly easy times to provide ample nectar and pollen options, fall is a critical time of the year for the remainder of the native bees to gather enough food to overwinter. New England asters, sneezeweed, and goldenrod are several plants that offer good food sources for late-season bees, Minnerath says. Even though the time for the honeybee to put up large stores of honey for winter has passed, every bit of nectar and pollen helps pull the hive through the winter.

1. Yellow columbine is native to the southwestern United States. 2. The Payette penstemon boasts clusters of vibrant bright-blue flowers. 3. A sunflower head is very valuable in an insect-friendly garden.

Creating Bee Habitats in the Garden

In addition to planting with a food source in mind, it’s important to consider how your garden fits the habitat needs of the bees in your region. Not all bees live in tidy hives. Bumblebees—a type of social bee like honeybees—live in a colony with a queen and female workers. Unlike honeybees, they live in the ground. Minnerath points out that bumblebee colonies last only one season, whereas honeybees persist throughout the year. At the end of the season, the old bumblebee queen, workers, and males perish, while the newly mated queens hibernate through the winter until the next season.

Because bumblebees need a place in the ground, consider keeping bare soil—particularly in out-of-the-way areas—available to encourage nesting. “Observe the pollinators you’re attracting and what they’re doing,” Minnerath says. “If they’re using specific areas to nest, protect those areas from disturbance.”

Some of the other native species, such as mason and leafcutter bees (Megachile sp.), use holes in wood or plant debris or even premade homes with tubes provided by gardeners. These solitary bees make ideal garden allies because they are champions of pollination and extremely docile due to their nesting and life cycles. There might be only a little pollen and an egg to defend, and it’s easier for the bee to look for more food and produce another egg instead of dying to protect it.

With social bees, Hunter says, “Everything is ‘save the queen!’ By contrast, solitary bees are gentle guys. They don’t have a need to sting because there’s nothing to protect. With a blue orchard bee, you can put your hand in front of it [on its way to its hole], and it’ll land on you.”

1. The yellow-banded bumblebee is one of several species whose numbers have declined in North America. 2. Golden currant blooms in April and May and is very popular with bumblebees. 3. A European honeybee is attracted to the brightly colored “butterfly weed” (a type of milkweed).