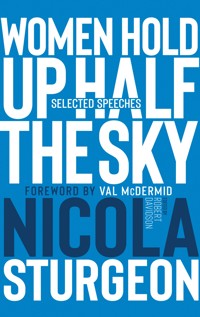

Women Hold Up Half the Sky E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The first woman to be elected First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon's impact on the future of Scotland and the United Kingdom makes her words essential reading. Independently selected by editor Robert Davidson, this collection of speeches from her time as First Minister addresses such crucial matters as the climate crisis, education, human rights and the European Union. Women Hold Up Half the Sky depicts a leader tackling not only immediate, pressing concerns but also mapping out a progressive agenda for the future.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 458

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PO Box 41

Muir of Ord

IV6 7YX

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or

transmitted in any form without the express

written permission of the publisher.

Introduction and additional material © Robert Davidson 2021

The original material of these speeches is available on the Scottish Government website and is freely available to use and re-use.

Foreword © Val McDermid 2021

Cover photographs reproduced from the Scottish Government Flickr account under license.

The moral right of Robert Davidson to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-60-1

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-61-8

CONTENTS

Foreword by Val McDermid

Introduction

1: MY PLEDGE TODAY IS SIMPLE BUT HEARTFELT

Holyrood, Edinburgh, 19th November 2014

2: BRIDGE TO A BETTER FUTURE

The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 25th February 2015

3: CONNECTIVITY AND INTEGRATION

Kirkwall, Orkney, 1st June 2015

4: THE IMPORTANCE OF EQUALITY

Washington DC, 10th June 2015

5: WE NEED MEN TO SHOW LEADERSHIP

Napier University, Edinburgh 25th June 2015

6: WOMEN HOLD UP HALF THE SKY

Beijing, 27th July 2015

7: 60,000 EXCITED LITTLE MINDS

Wester Hailes Education Centre, 18th September 2015

8: OUR RESPONSE WILL BE JUDGED BY HISTORY

St Andrews House, Edinburgh, 4th September 2015

9: HUMAN RIGHTS ARE NOT ALWAYS CONVENIENT BUT . . .

Pearce Institute, Govan, 23rd September 2015

10: SCOTLAND AND ALCOHOL

Edinburgh International Conference Centre 7th October 2015

11: A VISION FOR THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS

Isle of Skye, 21st October 2015

12: FOOD BANKS AND THE HEALTH OF THE NATION

Edinburgh 30th October 2015

13: RESPONDING TO THE PARIS ATTACKS

Holyrood, Edinburgh, 17th November 2015

14: THE IMPORTANCE OF NATURAL CAPITAL

Edinburgh International Conference Centre, 23rd November 2015

15: WORKERS’ RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS

Glasgow University, 24th November 2015

16: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

St John’s Smith Square, Westminster 29th February 2016

17: STEP IT UP FOR GENDER EQUALITY

Holyrood, Edinburgh, 5th March 2016

18: REFLECTIONS ON THE EU REFERENDUM

Edinburgh, 25th July 2016

19: THE DEFINING CHALLENGE OF OUR TIME

Reykjavik, Iceland 7th October 2016

20: A SPECIAL AND UNBREAKABLE BOND

Leinster House, Dublin, 29th November 2016

21: THE UNDERPINNING PRINCIPLE OF THE STATE

Stanford University, California, 4th April 2017

22: WOMEN IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION

United Nations Building, New York, 5th April 2017

23: THE IMPORTANCE OF TRUTH

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow 12th April 2017

24: DIVERSITY IN THE MEDIA

Edinburgh International Conference Centre 17th August 2017

25: THE ROLE OF INCOME TAX

Edinburgh, 2nd November 2017

26: HISTORICAL SEXUAL OFFENCES, AN APOLOGY

Holyrood, Edinburgh 7th November 2017

27: THE BEST POSSIBLE PLACE TO BE

Verity House, Edinburgh, 16th January 2018

28: A HUNDRED YEARS OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

Holyrood, Edinburgh, 6th February 2018

29: ON CHILD POVERTY AND CHILDREN’S RIGHTS

Beijing, 10th April 2018

30: THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION

Shanghai, 11th April 2018

31: CATHOLIC EDUCATION IN SCOTLAND

Glasgow University, 4th June 2018

32: OUTWARD-LOOKING AND OPEN FOR BUSINESS

Mansion House, London, 29th January 2019

33: HONOURING THE EDINBURGH SEVEN

Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh, 30th January 2019

34: THE MARINE ECOLOGY

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, 20th February 2019

35: A CALL TO SERVICE

Assembly Hall on the Mound, Edinburgh, 22nd May 2019

36: TWENTY YEARS OF DEVOLUTION

Edinburgh, 18th June 2019

37: THE COUNTRIES MOST AFFECTED

Glasgow Caledonian University, 28th June 2019

38: GROWTH IS NOT AN END IN ITSELF

Edinburgh, 29th July 2019

39: THE IMPORTANCE OF LITERATURE

Edinburgh International Conference Centre, 25th August 2019

40: A CUP OF KINDNESS

Brussels, 10 February 2020

A note on the transcriptions

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

What are political speeches for? Propaganda or information? Personal advantage or public interest? Winning over voters or damning opponents? Charming us or conning us, or both?

All of the above, obviously. But from time to time, a politician comes along who’s less interested in the fact of power than in what you can do with it. Even more rarely, we’re confronted with a politician who believes above everything else that they should use their power for the benefit of their citizens. And beyond that group, when the opportunity arises.

In the mouth of such a politician, the political speech becomes something different. It becomes something worth listening to, because it escapes the bounds of self-interest or narrow party concerns. It informs us and it challenges us to take a hard look at our own preconceptions.

This is a collection of speeches that does just that.

In these pages, we see Nicola Sturgeon’s passions laid bare. There’s no empty sloganeering here. Instead, we see a programme for government that’s underpinned by her aspiration for a fairer, healthier, happier nation. Of course, at the heart of it is her absolute conviction that the best route to achieving that is via independence.

But whether you agree with that keystone of her ambition, it’s hard to deny the humanity, decency and necessity of the things she advocates in these speeches. Whether she’s talking to heads of governments about Scotland’s place in Europe or to the Scottish Grocers’ Federation about food banks, the positions she outlines are always informed by compassion and sometimes by an anger that’s visible between the lines. These are not empty emotional manipulations either; they’re always accompanied by ambitions and suggestions for making things better. As she herself says, ‘We are more likely to make progress in the right direction by aiming high than we ever will by being over-cautious.’

So what are those passions we see laid bare here? Independence for Scotland, obviously. Social justice; equal educational opportunities; the importance of literacy and literature; equal access to health and social care; tolerance; feminism; workers’ rights; holding out a hand to refugees; and building a strong and green economy to sustain all of these.

It may seem an idealistic and unrealistic set of goals. But in the years since Nicola Sturgeon has been First Minister, her government has made many steps in the right direction. They’ve also made mistakes, just like every other government in human history. Any political system relies on human beings to deliver. And human beings are . . . well, only human.

But another benefit of a collection of speeches like this is that it looms in the landscape as an irrefutable monument to what Nicola Sturgeon has promised to do her best to deliver. Speeches like this are hostages to fortune; they allow both her rivals and her friends to hold her feet to the fire when her government falls short.

I’ve been fortunate to spend enough time in the company of Nicola Sturgeon to know that what we see is what we get. I’ve never seen the slightest sign of some ‘secret Sturgeon’ sneering behind her hand at the people she governs or engaging in Machiavellian intrigues for her own benefit. The woman who emerges in private is the woman we see through the lens of these speeches. Except that in private, she’s funnier than the political speech allows.

If you want to get to know the woman who leads the Scottish Government, this is a good place to start.

Val McDermid

Edinburgh

March 2021

INTRODUCTION

A beloved cousin who died too soon told me that freedom is a myth for as long as other people are in your life. Call that statement cynical or call it a platitude, it encapsulates much that is relevant to any independence debate.

Take freedom, which can only be a temporary condition because, when the newly liberated party meets with others, or accepts obligations as they must surely do, their choices are constrained. Independence, on the other hand, thrives on interactions and choice, and is in constant development with new challenges, new relationships and changing values. Freedom is static where independence must constantly adapt. Freedom is hampered by obligations where independence is fulfilled by them. Winnie Ewing, one of my great heroes, famously and frequently declared, ‘Stop the world, Scotland wants to get on’.

The independence debate in Scotland has too easily and too often been characterised as passionate, hand-on-heart nationalism, which perhaps has its place in an energising myth, but the real business is about decision-making and direction. Nationalism is a noun badly in need of an adjective because, as I think is obvious, there is serious qualitative difference between the cultural and ethnic varieties.

It was Scotland’s fourth First Minister, Alex Salmond, who introduced the term civic nationalism to the debate, which followed the acceptance by Jack McConnell, his predecessor, of a national need for immigration, for ‘others’, to counter a shrinking population level. These contributions, in my view, along with shared sovereignty within the European Union, shifted the argument from heritage and tradition onto the Enlightenment values of tolerance and equality, along with the economy. In this way the implicit question in my cousin’s statement, not so much who are the ‘others’ as who are ‘we’, was answered positively: whoever is in our territory.

So much for freedom, the ‘others’ and myth. The final element in my cousin’s statement is time, the idea that change will happen in time. A Scottish Parliament seemed a forlorn hope through the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher’s first Scottish Secretary, George Younger, declared that ‘devolution is dead’ often enough and with such authority that most ideas would have stuck. This one did not.

Politicians will try to ‘draw a line under it’ when a sliver of the vote goes their way, as happened after the 1979 referendum on John Smith’s Scotland Act, but are vulnerable to the slow regeneration of hope against a background of perceived injustice. Devolution became a central tenet of the Labour Party in Scotland under the leadership of Donald Dewar whose jousts with Mrs Thatcher’s second Scottish Secretary, Malcolm Rifkind, became an unmissable feature of Scottish political life.

Two more Scottish Secretaries would hold office, Michael Forsyth and Ian Lang, before Labour regained power in 1997 under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The second devolution referendum followed on the 11th September that year, one of the great days of my life, and nothing could be the same after a vote of 74% in favour of the proposal.

Donald Dewar became the first First Minister but, after only seventeen months in office, tragically died following a brain haemorrhage. Henry McLeish followed but stood down after only a year. Jack McConnell steadied the ship, remaining in office until 2007, when the Scottish National Party was returned as a minority government. Alex Salmond achieved majority status in the election of 2011 and remained in office until after the Independence Referendum of 2014.

If ever a format was tired it was the Westminster model, weighed down as it was, and remains, by weary traditions and ritual. Five of the fifteen post-war prime ministers to 2020 attended Eton. Three more went to costly fee-paying schools. Its second house has historically been filled, as Lloyd George put it, by men (now also women) ‘chosen accidentally from the ranks of the unemployed’, by political appointments, and by some who simply bought their peerages from the ruling party.

In comparison, the Scottish Parliament is proportional and ferociously modern, banning smoking in public places, legalising equal marriage, ending period poverty for all women – first in the world to do so – and introducing Britain’s first gender-balanced cabinet. It is directly answerable to the Scottish people, accessible to all, and housed in a remarkable new building that acknowledges the past but is fit for the 21st century.

Utterly dominant in debate, Alex Salmond swept all before him until, throughout Scotland and the United Kingdom, extending to the United States and beyond, he came to be respected as the genuine voice of the nation and, with that, both his authority and that of the office grew. Where the parliament might formerly have carried with it a suggestion of municipality, it now had the textures of real authority. Where the First Minister’s role once had a sort of Lord Provost colouring, it took on presidential overtones. Administration and leadership had conjoined.

Scotland’s head of state remains the monarch, for long a politically silent figure. The Prime Ministerial incumbent is the most obvious surrogate, but the Thatcher years alienated the office from many Scottish people. There was a void and Alex Salmond filled it. His deputy throughout these years in office would be his successor, the author of these speeches, Nicola Sturgeon.

Born in 1970, she describes herself in the first as a ‘working-class girl from Ayrshire’. After joining the Scottish National Party as a teenager, she took her law degree from the University of Glasgow. Later she worked for the Drumchapel Law Centre in the same city, reinforcing the working-class outlook that would be so beautifully expressed in her Jimmy Reid Lecture (Speech 15). However, she would move beyond the ideas of her parents’ generation, as will be seen.

When the Scottish Parliament reconvened in 1999 she was among the first intake of MSPs. An intake, incidentally, that included more women than had ever been elected to Scottish seats at Westminster. John Swinney took over as leader of the party in 2000 when Alex Salmond relinquished the position but stood down after four unsuccessful years. Mr Salmond resumed the leadership from his Westminster base with Nicola Sturgeon not only deputy but also leader in the Scottish Parliament. Together they won the Scottish election of 2007 and he returned in triumph with her at his side. From then until late 2014 they formed an invincible and inseparable pairing.

Between 2007 and 2012 she served as Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing, after which she covered Infrastructure, Investment and Cities, but other things were going on in her life. In 2010 she married party official Peter Murrell to form what was often described (not always approvingly) as a ‘power couple’. Of more relevance to these speeches is that she continued her lifetime’s habit of reading widely and voraciously and so, it seems to me, exposed her mind to more progressive thinking than do most political leaders. Any list of dedicated readers among such would include John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Barack Obama, and Donald Dewar himself, a distinguished minority of a liberal, progressive persuasion. They could write well, too.

Familiar with the Scottish canon, she also read contemporary literature from such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Arundhati Roy, and Ali Smith, authors she would interview at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. When, as First Minister, she began to tweet her current reading, always appreciatively, her account became a point of interest to readers and publishers across Britain. Between this, and her direct relationships with both left and right in the political spectrum, her socialism transmuted into a more socially progressive brand of politics with feminism at its core, a feminism that was in her leadership from the start but that became increasingly apparent as her authority grew. That said, the speeches that follow are equally imbued with practical solutions.

Beginning in late 2014 with her acceptance of the post of First Minister, the speeches presented here end early in 2020 with her address to the European Policy Centre. By that time, Scotland had been removed from the European Union as part of the Brexit process, but was still within the period of transition. To my mind, this closing speech is among the most heartening of the forty in this book.

Others of special note include Speech 4 on equality, and Speech 6, which takes its title, as does the book, from an aphorism usually ascribed to Chairman Mao1, but that may in its turn have been lifted from common currency. It is used here, regardless of its provenance, because it is appropriate, beautiful, and true. Speeches 8 and 9 accurately reflect not only the feelings of Scottish people on the plight of refugees, but also those of humanitarian thinkers across Europe and America. Speeches 10 and 12 speak to the health of the nation, which was and remains a preoccupation of the Scottish Government.

Speeches 16 and 18 were delivered on either side of the EU referendum and are of historic importance.

I am especially fond of Speech 23 as it predates other fine writing on a subject – the importance of truth – that would in previous times have seemed so transparently obvious it would not have required elucidation. More detailed writing would follow from others, but here is an early warning from Scotland’s First Minister.

Speeches 28 and 33 could stand as representative of feminist writing in Scotland and are a joy to read. So too are Speeches 19 and 34 on the environment, and 38 which is related. Speeches 29 and 30 were given in China on a visit which was criticised on the grounds of that country’s human rights violations, but that address those very rights while seeking to establish common ground and build bridges.

The period contains many events of local (meaning British) and international significance. In 2014, David Cameron was still Prime Minister, relieved that No had prevailed in Scotland’s first independence referendum. In 2015 he won a British General Election for the Conservative Party, ending their coalition with the Liberal Democrats. In the same election, the Scottish National Party won a historic victory, taking 56 of the 59 available seats on fifty per cent of the vote, an astonishing performance.

2016 was bung full politically. The Scottish National Party won handsomely again in the Scottish election but lost its overall majority. When the EU (Brexit) referendum was run Leave won by a tiny majority, although much controversy would ensue over the illegal gathering and use of data and, indeed, the misuse of truth. Noting that Scotland emphatically voted Remain, the author J. K. Rowling, a defender of the Union in 2014, tweeted ‘Goodbye UK’. Many others wrote at greater length but with no additional eloquence.

David Cameron resigned and was replaced by Theresa May who promptly activated Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty2, committing to what had been an advisory vote without consideration of the nations who had voted to remain, Scotland and Northern Ireland, or their parliaments. The Labour Party supported the move. Negotiations were entered with the European Union and, frankly, chaos reigned.

In 2019 Theresa May stepped down to be replaced by Boris Johnson who called a general election late in the year, on 12th December, when a divided Labour Party presented the main opposition . . . except in Scotland . . . and won by a landslide. At 11.00 pm on the 31st January 2020 Britain formally left the EU and began its long flounder through the transitional period.

All that said, it would be wrong to view these speeches as a commentary on events. Rather they represent a national leader meeting obligations and responding to changing times. Closing, as they do, when the far right was in the ascendant across much of the world, not least in America, and a global pandemic was about to strike, they address the international condition almost as much as that of a small nation off the coast of Europe. There is resistance, but the values of the past are slowly, globally, falling away and there can be no return to whiteness, island mentality, or patriarchy. The future formation will be diverse, European, and feminist, and is heralded in the following pages.

To my mind, the story of the Enlightenment continues in these speeches. We might say the New Enlightenment. Reading and rereading them, I was increasingly impressed not only by Nicola Sturgeon’s command of detail but also by the guiding spirit that shines through, and came to see that the Scotland I want dwells here among the thickets of details and ideas. Open-minded and warm-hearted, industrious, fair; a forward-looking and progressive nation. Above all, she speaks from the same common humanity that inhabits the social tradition she imbibed with her mother’s milk. Essentially, a humane outlook that has survived all manner of change and, I dare say, will continue to do so.

1

MY PLEDGE TODAY IS SIMPLE BUT HEARTFELT

Given to the Scottish Parliament

Holyrood, Edinburgh, 19th November 2014

In this, her first speech as First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon (NS) spoke to a noticeably cheerful debating chamber, which held an overall majority for her party. After referring to the origins of the parliament, she paid tribute to her four predecessors in office, including a fulsome appreciation of her career-long friend and mentor Alex Salmond. She also struck the principal keynote not only of her political life to date, but also her prospective tenure: gender equality.

Presiding Officer, I thank you for your kind words, and my fellow members of Parliament for giving me the honour and privilege of being your nominee as the next First Minister of Scotland. My pledge today, to every citizen of our country, is simple but heartfelt. I will be First Minister for all. Regardless of your politics or point of view my job is to serve you, and I promise to do so to the best of my ability.

This is a special and proud moment for me, a working-class girl from Ayrshire given the job of leading the Government of Scotland. It is also a big moment for my family, and I am delighted that they join me here today . . . particularly delighted, relieved even, to note that (so far) my niece and nephews appear to be on their best behaviour!

I am so grateful to my family, but especially to my Mum, Dad, sister, and husband, for the unwavering support they have given me in everything I have chosen to do. Now that I am First Minister, I suspect that I am going to need that support more than ever, but I am lucky in knowing that it will always be there. I also want to thank my constituency office staff for the invaluable work they do for me and for my constituents in Glasgow Southside.

Presiding Officer, like you, I have been a member of this Parliament since its re-establishment in 1999, which means that I have had the opportunity, at close quarters, to watch and learn from all of my predecessors as First Minister. Each of them in their own unique ways have been passionate and diligent advocates for Scotland. I have the greatest respect for all of them, the late Donald Dewar, Henry McLeish, Jack McConnell, and Alex Salmond, and am genuinely humbled that my name will be added to that distinguished list.

That our Parliament and Government, in just fifteen short years, have come to be so firmly established and, dare I say, respected in our national life, is testament to the quality of their stewardship and leadership. However, I am sure members will understand why I want to pay a particular tribute to Alex Salmond today.

Without the guidance and support that Alex has given me over more than twenty years, it is unlikely that I would be standing here. I owe him a personal debt of gratitude and it is important to me to put my thanks on the public record today. His place in history as one of Scotland’s greatest leaders is secure, and rightly so. However, I have no doubt that he has a big contribution yet to make to politics in Scotland. I will continue to seek his wise counsel and, who knows, from time to time he might seek mine too.

To become First Minister is special and a big responsibility. To make history as the first woman First Minister is even more so, and I am reminded of a quote from Florence Horsburgh, a Conservative MP for Dundee. In 1936 she became the first woman to reply to what was then the King’s Speech in the House of Commons. She said:

‘If in these new and novel surroundings, I acquit myself but poorly, when I sit down I shall at least have two thoughts for my consolation – it has never been done better by a woman before, and whatever else may be said about me, in the future from henceforward, I am historic.’

I can sympathise with the sentiment but hope not to need any such consolation! Indeed, I much prefer this quote from the same speech: ‘I think of this occasion as the opening of a gate into a new field of opportunity.’

I hope that my election as First Minister does indeed help to open the gate to greater opportunity and that it sends a strong, positive message to girls and young women. Indeed, to all women across our land. There should be no limit to your ambition or what you can achieve. If you are good enough and work hard enough, no glass ceiling should stop you achieving your dreams.

What I do as First Minister will matter more than the example set by simply holding the office. Leading on equal representation, and encouraging others to follow, addressing low pay, improving childcare, are the obligations I now carry, and I am determined to discharge them on behalf of women across our country.

My niece, who is in the public gallery today with her brother and cousins, is eight years old. She does not yet know about the gender pay gap, or underrepresentation, or barriers such as high childcare costs that make it so hard for women to work and pursue careers. My fervent hope is that she never will and that, by the time she is a young woman, she will have no need to know about any of these issues because they will have been consigned to history. If, during my tenure as First Minister, I can play a part in making that so, for my niece and for every other little girl in this country, I will be happy indeed.

I am taking on the responsibilities of First Minister at an exciting time in our nation’s history. All of us, regardless of party, have been inspired and challenged by the flourishing of democracy that we have witnessed during and since the referendum3. Democratic politics in Scotland has never been more alive, and the expectations that people have of their politicians and their parliament have never been higher. There is a burning desire across our country to build a more prosperous, fairer, and better Scotland and not only among those who voted Yes. Those who voted No want a better country too, and I intend to lead a government that delivers on those aspirations.

My role as First Minister will be to help build a Scotland that all who live and work here can be proud of. A nation both social democratic and socially just; a Scotland confident in itself, proud of its successes and honest about its weaknesses; a Scotland of good government and civic empowerment; a Scotland vigorous and determined in its resolve to address poverty, support business, promote growth and tackle inequality. These are the points against which my government will set its compass, and I earnestly believe that, in doing so, we will reflect the wishes, hopes and desires, even the dreams, of the Scottish people.

Of course, we will have our differences in this chamber as to the best way forward. We must never shy away from robust debate but should strive always to be constructive and respectful. I want all members to know that when we are on common ground (and I want to find as much of that as possible), you will find in me a willing and listening ally.

It will surprise no-one to hear that I will always argue the case for more powers, indeed the full powers of independence, for this Parliament. I believe that the more we are able to do the better we can serve the people, but will do my utmost to govern well with the powers we have.

My daily tasks will be to protect and improve our NHS, support our businesses at home and abroad, ensure that all children get the chance to fulfil their potential, and keep our communities safe from crime.

I intend to lead a government with purpose, that is bold, imaginative, and adventurous, although tough decisions must be made and I may not always get them right. It is not necessarily the case that all manner of things shall be well. There will be challenges, but I will strive to meet them positively and with fortitude, inspired and sustained each day by the potential of this country and the people who live here.

I want to end with another quote, this time from the Earl of Seafield, the Chancellor who signed away Scotland’s sovereign independence in 1707. As he did so, he lamented, ‘There’s ane end of ane auld sang’. That song lay lost for 292 years, until we reconvened this parliament in 1999, but this First Minister intends to ensure that we adorn it with new verses that tell of a modern and confident Scotland, fit for purpose and fit for all her people.

Together, let us now get on with writing that story.

2

BRIDGE TO A BETTER FUTURE

Given to the David Hume Institute

The Royal Society of Edinburgh, 25th February 2015

Speaking to the subject ‘the sort of country we want Scotland to be’ NS picked up on her constant themes of education and equality, seeming to balance the infrastructure project she inherited, the Queensferry Crossing, with her own intended signature project of increased care and learning provisions. Both the longest and most data-heavy speech included, this speech is impressive not only for its detail and scope, but also in its idealistic faith in the power of education to level upwards. Also interesting is the first use in this selection of the word ‘wellbeing’ that would later become almost an organising principle of her government.

When we were choosing whether to vote Yes or No4 last year, we engaged in one of the most passionate, wide-ranging and fundamental debates that any nation can have. We had to ask ourselves what kind of country we wanted to live in. We thought of our concerns about the present, and hopes and dreams for the future, and came to our conclusions. Anyone travelling the country then, as I did, heard time and time again, from No voters as well as Yes, an overwhelming desire to build a better and fairer society as well as a wealthier one.

The referendum did not turn out as I hoped, but that assessment and reassessment has strengthened and energised our country. The challenge now is to harness its energy to build a better Scotland, to turn those aspirations into reality.

When I became First Minister, nearly one hundred days ago, I set out a programme for government based on the three priorities of prosperity, participation, and fairness. We aim to build prosperity because a strong economy underpins the wellbeing of every community in Scotland, and encourage participation because we want to empower and enable people to improve their own lives and those of others. We will promote fairness because we know there are too many barriers standing in the way of too many people, whether from background, income, geography, gender, or disability. We also know that inequality is bad, not only for individuals and society, but also for our economy.

The OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] estimates that inequality reduced the UK’s economic growth by nine percentage points between 1990 and 2010. To put it simply, if we succeed in making Scotland more equal, we will not only raise the life chances of this and the next generation, but also enhance our economic prosperity.

That is why I strongly believe that a strong economy and a fairer society should no longer be viewed as competing, but instead as mutually reinforcing objectives.

As leader of the Scottish Government, I am determined that we will use all the powers at our disposal, now and in the future, to progress these twin goals but, of course, we cannot ignore the wider context. The hard fact of the matter is that the current UK Government’s spending cuts, largely endorsed by the main opposition party, make tackling inequality more difficult.

The cuts we have seen so far have had a disproportionate impact on women, disabled people, and families on low incomes. The UK parties’ plans for even more austerity would hurt those groups again, and it seems to me that no politician can be taken seriously on poverty and inequality if they are not also prepared to challenge the current Westminster model. It is also important to make that challenge because austerity has been bad for the economy. Low growth is the major reason that the government has missed its deficit reduction targets by a total of £150 billion . . . which is why the Scottish Government has set out an alternative approach based on limiting real terms spending growth to 0.5% a year.

A policy of very modest spending increases would see the debt and deficit reduce as a proportion of national income every year from 2016–17, and free an additional £180 billion across the UK (over the next parliament), which could be used to invest in infrastructure and innovation, protect the public services we all depend on and ease the pressure on the most vulnerable.

By offering an alternative to the austerity agenda, we can ensure that fiscal consolidation is consistent with the wider vision of a society striving to become more equal as part of becoming more prosperous and fiscally sustainable. Education is a vital part of that vision.

Education is, and will continue to be, a defining priority for the government I lead. It is also a personal passion. The education I received at Dreghorn Primary, Greenwood Academy, and Glasgow University, is the major reason I am able to stand here as First Minister of Scotland. So, it is important to me personally that every young girl and boy growing up today, regardless of their background, gets the same chances that I did.

This evening, I will talk about how we achieve that, focussing in turn on the early years . . . on school education . . . and then opportunities for young adults. In doing that, I will point towards areas where we need to do better, but my starting point is an optimistic one.

This country is incredibly fortunate. A commitment to education is ingrained in our history, part of our DNA and our very sense of ourselves. We pioneered the idea of universal access to school education and sparked the Enlightenment, the spirit of which still inspires the David Hume Institute. Hume himself argued that ‘The sweetest . . . path of life leads through the avenues of science and learning’. We discovered, relatively early, that education does not just sweeten life or bring enlightenment. Widening access to education also brings economic benefits. During the 18th and 19th centuries, because Scotland educated more people to a higher level than most other countries, we pioneered the industrial revolution and provided a disproportionate number of the world’s great thinkers, scientists, and inventors.

In many ways, our education system still lives up to its reputation. Actually, it is better than ever. More children are better educated than at any time in our history. Higher exam passes are at record levels. Curriculum for Excellence5 is being successfully implemented. School leaver destinations are the best on record. Of the students who left school in 2014, more than nine out of ten are in employment, training, or education. We have more world-class universities per head than any other country except Switzerland.

A survey last summer from the Office of National Statistics showed that, in terms of college and university qualifications, Scotland has the best-educated workforce anywhere in Europe and that is a remarkable asset. It is an incredible advantage for Scottish businesses looking to recruit and overseas companies looking to invest. It also provides a firm foundation for future economic growth.

We all understand that, although these achievements are hugely significant, they are not the whole story. So today, I want to highlight some of the areas where we can and must do better. In particular, I want to focus on how inequality in attainment, starting in the very early years, and persisting into adulthood, weakens our society, holds back our economy, and constrains the life chances of too many fellow citizens.

The basic problem can be illustrated with just one statistic. In terms of qualifications, school leavers from the most deprived twenty per cent of Scotland only do half as well as those from the least deprived areas. None of us should accept a situation where so many people are unable to realise their full potential. It lets too many young people down and diminishes us all. Those figures relate to school education, but the challenges start before that. The Growing Up in Scotland Study calculated the difference in vocabulary between children from low-income and high-income households. By the age of five, the gap was already thirteen months.

The first step in tackling the attainment gap, is to make sure every child gets the best possible start in life.

I will talk about formal care and learning in a moment, but the issue is much broader than that. We need to think about the wellbeing of babies and parents from pregnancy onwards, which is why our Early Years Collaborative is so important. Since it was established in 2012, it has brought together health workers, carers, parenting organisations and others from every part of the country. It ensures that evidence and research is shared, so that approaches which work in one area can be adopted elsewhere.

The Collaborative has already identified several priorities, and community planning partnerships are now working on these. For example, we are looking at better early assistance for pregnant mothers; encouraging better attachment between mothers and young children; and helping parents to support learning. All of this will have a big impact not only on attainment, but also on children’s happiness and emotional wellbeing.

The Collaborative is attracting international attention. It is helping to ensure that good practice becomes common practice. It is already helping to create a better future for young children in Scotland.

The establishment of the Collaborative has accompanied a significant investment in early years learning and care. In August, we will further extend funded childcare places to disadvantaged two year olds, having already expanded the care available to three and four year olds from 412 hours a year in 2007 to 600 now. By the end of the next parliament, it will be more than 1100 hours, meaning that funded childcare will match primary school provision.

There are two significant things about this increase. The first is its economic impact. I was struck by a comment President Obama made in his State of the Union Address last month. He argued that: ‘It’s time we stop treating childcare as a side issue, or as a women’s issue, and treat it like the national economic priority it is’, making the fundamental point that childcare is an economic necessity. I would describe it as essential economic infrastructure, as fundamental in its own way to enabling parents to work as the transport infrastructure that gets them there every morning. Better childcare empowers parents, especially mothers, to return to work, and that is why, last November, the CBI [Confederation of British Industry] cited more childcare as the top priority in their ‘Plan for a Better Off Britain’.

The second point is perhaps even more important. Childcare is not just about enabling parents to return to work. It is about providing the caring and learning environment that every child needs to flourish. We already know that, by age five, children attending early learning and childcare settings with high inspection ratings have better vocabulary skills than their peers, regardless of their family’s income level. Vocabulary skills are a key indicator of later attainment. So, by improving the quality of learning and care by supporting workforce guidance and development we will improve attainment and reduce social inequalities. Curriculum for Excellence does not start in Primary 1. It starts at age three in our nurseries.

The key point is this. Early Learning and childcare promote opportunity twice over, enabling parents to enter the workforce and provide a better standard of living while helping all children to make the most of their potential later in life. It is one of the best investments any government can possibly make. In my view, it is central to any enlightened view of what modern Scotland should look like and that is why it is such a driving priority of my government.

Today I confirm my intention that spending on early learning and care will double over the course of the next parliament, in addition to the extra capital spending we will provide.

The great capital investment project of this parliament is the Queensferry Crossing. If I am re-elected next year, I intend that the great infrastructure project of the next parliament will be even more transformational. It will be the investment in care and learning facilities needed to ensure early years provision matches primary school provision. These facilities will create a bridge to a better future for children and families across the country.

High-quality learning and care in the early years will help reduce the attainment gap in schools, but we need to do more within schools as well. Understanding how much we owe to the passion, commitment, and expertise of our teachers, we are determined to invest to protect teacher numbers.

Teachers are the major reason for the significant successes I mentioned, the implementation of curriculum for excellence, the record exam results, and the high number of school leavers in education, employment, or training, but we need to do more to support them and their schools. Especially schools with significant intakes from more deprived communities.

In January we introduced free school meals for all primary school children, because making nutritious lunches available to everyone, without the stigma of means testing, will benefit every child’s health, education, and wellbeing. Two days ago, I visited Blue Gate Fields Junior School in Tower Hamlets, which participated in the London Challenge attainment initiative. 70% of its pupils are eligible for free school meals, almost three times the average for England. Notwithstanding that, it is in the top 20% of schools in England for reading, and in the top 40% for writing and maths. Ofsted has reported that it is ‘an outstanding school in almost every respect’.

Some of the coverage around my visit expressed surprise that I was learning from London, but I have never pretended that Scotland has a monopoly on wisdom in education or any other area. Just as other countries study Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence, and the Early Years Collaborative, so we should be prepared to adopt good ideas from elsewhere. We are not just looking to London. In Canada, Ontario has achieved dramatic improvements in literacy and numeracy.

Not all the lessons of the London Challenge can or should be used in Scotland, but some are applicable. Leadership has been a factor in the success of many, and I also see great examples of good leadership in schools across Scotland. Because we are looking to build on that, I announced on Monday that the new Qualification for Headship, which will come on stream later this year, will be mandatory for all headteachers by 2018/19.

One lesson that London and Ontario demonstrate, is that when efforts and resources are targeted it is possible to achieve dramatic improvements. Therefore, I launched the £100 million Scottish Attainment Challenge two weeks ago. The fund will be focussed initially on primary schools in the local authorities with the highest concentration of pupils living in deprived areas, aiming to improve literacy, numeracy, health, and wellbeing.

If we can close the attainment gap when children are young, the benefits will continue into secondary school and beyond. The real prize though, is not simply the additional £100 million we are investing. It lies in the potential to apply what we learn from the programme across the £4 billion school education budget. The Challenge will add to the other steps taken, such as our national numeracy and literacy drive ‘Read, Write, Count’, and our funding of attainment advisers in every local authority.

What the Scottish Attainment Challenge does, together with those other steps, is provide new impetus and focus on closing the attainment gap. We are making support available to all schools, while also placing additional assistance and resources where they are needed most. We are raising standards everywhere but want to see the biggest improvements in the places with the greatest need. That, in my view, is a moral imperative. It is not acceptable that any child is held back because of their background or the circumstances of their birth.

Free higher education tuition has become a touchstone of this government’s commitment to equality of opportunity. As someone who benefited from it, I am determined to preserve the principle that access to university is decided by ability to learn, not ability to pay.

Protecting the principle of free education, vital though it is, is still not enough. We also need to remove the other barriers that prevent too many young people from our most deprived communities pursuing a university education . . . and we have work to do! Children from the most deprived fifth of communities make up only a seventh of undergraduate intakes.

When I became First Minister, I unambiguously set the ambition that a child born in one of our most deprived communities should, by the time he or she leaves school, have the same chance of going to university as one born in our least deprived communities. Let me stress that. The same chance. Not just a better chance than they have today, but the same chance as anyone else. In other words, where you are born and brought up and your parents’ circumstances must not be the driver of how likely you are to go to university.

The work outlined for early years and in our schools will be fundamental to achieving that ambition, as will work by the government and our universities. This year the government funded 730 additional places to widen access for students from more disadvantaged backgrounds, but to ensure we are doing everything we can, as early as possible, we are establishing a Commission on Widening Access.

The Commission will propose milestones, measure progress, identify improvements, and be central to ensuring that our ambition of equal access becomes a reality. That is part of a far broader approach to post-school learning. After all, the key test we need to apply is not whether learning takes place in college, at work, or in university. It is whether the learning is relevant, engaging, and widens people’s opportunities.

Since 2007 we have focussed colleges on promoting skills which help people to work and support economic growth. The number of students gaining recognised qualifications has increased by a third in the last five years. We retained educational maintenance allowances when the UK Government scrapped them in England, invested in modern apprenticeships directly tied to job opportunities, and launched a national campaign to promote youth employment.

All of this has achieved results. We currently outperform the rest of the UK on all three youth employment indicators: higher youth employment, lower unemployment, and lower economic inactivity rates . . . but, still, we need to do more.

Last year, the Commission for Developing Scotland’s Young Workforce published its final report and we are investing £28m between this year and next to implement its recommendations. We have already established an ‘Invest in Young People’ group, bringing together industry, local government, further education, and trade unions. It is worth setting out what all this will mean.

A closer relationship between industry and education, enabling courses to reflect what companies need. Apprenticeships up from 25,000 a year at present to 30,000 a year by 2020. Better careers advice at an earlier age. Support for employers (for example, to gain the investors in people accolade). Concerted action to improve participation of underrepresented groups so the gender segregation in too many modern apprenticeships (where only 5% of engineering apprentices are female, and just 3% of childcare apprentices are male) eventually diminishes and disappears. Men and women will choose work to match their talents and interests, rather than outdated expectations.

From supporting mothers in the early stages of pregnancy, to helping people gain their first experience of work, the overriding message I want to leave you with tonight is that my government is committed to doing everything it can to promote opportunities and reduce inequalities.

Of course, this commitment is not something that government, schools, colleges, and universities can achieve on their own, although our role is hugely important. It must be part of a shared endeavour. Earlier today, I announced a further £6m of funding for the Scottish Council of Voluntary Organisations, to deliver its Community Jobs Scotland programme. Using that money, it will deliver at least 1,000 job training opportunities across all thirty-two local authority areas. At least three hundred will be for vulnerable young people, such as care leavers and ex-offenders. A further hundred will be for disabled people. It is a good example of how the third sector is working with us to help young people into work.

Businesses also have an important part to play. When we launched the ‘Make Young People Your Business’ campaign we got, from many companies, a magnificent response that has made a difference to many young people’s lives. What those companies found was that employing young people brought significant benefits. Doing the right thing was in their own best interests. Business will not have a role in every part of education, but we will seek to work together on issues where they do have an interest, whether entrepreneurship in schools or the delivery of modern apprenticeships.

The approach to education I have outlined tonight is part of a wider approach to sustainable growth, which will also be clear in the Government Economic Strategy being published next week. Fundamentally though, it is about achieving the basic ideal that I think of when I am asked the question: what kind of country do you want Scotland to be?

To put it simply, I want Scotland to be a land of opportunity. A country where every individual, regardless of background or race or gender, gets the chance to fulfil his or her potential.

Can that be achieved? Yes, and education is the key. I quoted David Hume earlier. In the same passage he goes on to say that ‘whoever can either remove any obstruction (to education), or open up any new prospect, ought . . . to be esteemed a benefactor to mankind’.

The removal of obstructions to education, and the opening of new opportunities, has been the focus of many of the major initiatives of my first hundred days as First Minister, and will receive sustained attention for as long as my government holds office. Education is not only part of our sense of ourselves, it is the key to a better future for young people growing up today, and it must be at the heart of the fairer and more prosperous country we all seek to build.

3

CONNECTIVITY AND INTEGRATION

Given to the Convention of the Highlands and Islands6

Kirkwall, Orkney, 1st June 2015

Since at least the 1960s, intermittent attention had been given by successive governments to infrastructure development in the Highlands and Islands. A plan for growth was published within that decade, the Cromarty Firth was bridged in the 1970s, the Kessock Bridge built in the 1980s, the Dornoch Bridge opened in 1991. However, even by the 21st century, roads between communities and to the south were inadequate and ferries too expensive. Land ownership and use had been a barrier to progress for generations, as well as a political fault line. Later, digital communication brought new challenges and opportunities to rural communities. Having been, no doubt, sensitised by her years as Cabinet Secretary for Infrastructure, Investment and Cities, implicit in these comments by NS is the idea that the Highlands and Islands have traditionally been seen as somehow a land apart and that a greater integration with the rest of Scotland was overdue.

The Scottish Government’s Programme for Government, and the economic strategy we published in March, emphasise the importance of creating a fairer nation as well as a more prosperous one. It therefore stands to reason that we want every part of Scotland to prosper and are determined to ensure that jobs and opportunities are available in rural and island communities. While welcoming this discussion on the specific challenges we face, I do wish to mention two issues which are important across the whole country.

The first is connectivity: improving the transport and digital links which connect island and rural communities with the wider world. The second is empowerment: how we give local authorities and local communities more power to take decisions for themselves.

To start with connectivity. Perhaps the biggest and quickest change will come from the investment in next-generation broadband. Here in Kirkwall, the first broadband exchanges came into use in February and 2,400 properties are now connected to a local fibre network. More work will start soon in Westray, Sandwick, Orphir and Birsay7. By the end of next year, seventy-five per cent of properties on Orkney will have access to next-generation broadband, as will eighty-four per cent of properties in the Highlands and Islands. We see the broadband project as being truly transformational.

Without public money, no commercial broadband would have been planned in Orkney or in many other places. What is now being achieved is hugely significant, but we are clear that connecting eighty-four per cent of the Highlands should be seen as a staging post rather than a final destination, and that is why Community Broadband Scotland is working with development trusts to explore how to deliver broadband services to the remoter islands. It is also why we welcome this opportunity to discuss with you how to extend broadband provision further.

We are determined that your digital infrastructure will enhance the sustainability and prosperity of your communities, and that the Highlands and Islands will not be left behind.