Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

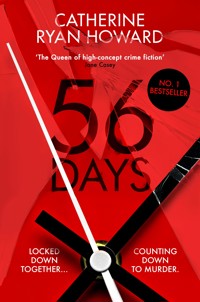

Winner of the An Post Irish Book Awards 2021 Crime Fiction Book of the Year A Book of the Year for 2021 in the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Irish Times ___________________________ ** THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER ** 'As good as suspense fiction gets' Washington Post No one even knew they were together. Now one of them is dead. 56 DAYS AGO Ciara and Oliver meet in a supermarket queue in Dublin and start dating the same week COVID-19 reaches Irish shores. 35 DAYS AGO When lockdown threatens to keep them apart, Oliver suggests they move in together. Ciara sees a unique opportunity for a relationship to flourish without the scrutiny of family and friends. Oliver sees a chance to hide who - and what - he really is. TODAY Detectives arrive at Oliver's apartment to discover a decomposing body inside. Can they determine what really happened, or has lockdown created an opportunity for someone to commit the perfect crime? 'Terrific ... you won't want to stop reading until the end' Karin Slaughter

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Catherine Ryan Howard’s debut novel Distress Signals was published by Corvus in 2016 while she was studying English literature at Trinity College Dublin. It went on to be shortlisted for both the Irish Crime Novel of the Year and the CWA John Creasey/New Blood Dagger. Her second novel, The Liar’s Girl, was published to critical acclaim in 2018 and was a finalist for the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for Best Novel 2019. That same year, Rewind was shortlisted for the Irish Crime Novel of the Year and was an Irish Times bestseller. In 2020, The Nothing Man was shortlisted for the Irish Book awards. She is currently based in Dublin.

_______________________________

To Iain Harris, because I couldn’t think of what to get you for your fortieth and also, just because

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of

Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Catherine Ryan Howard, 2021

The moral right of Catherine Ryan Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 162 7

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 163 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 164 1

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

TODAY

It’s like one of those viral videos taken inside some swanky apartment complex, where all the slim and fit thirty-something residents are doing star jumps behind the glass railings of their balconies while the world burns. But these ones stand still, only moving to look down or at each other from across the courtyard, or to lift a hand to their mouth or chest. Their faces are pale, their hair askew, their feet bare. Dawn has barely broken; they’ve just been roused from their sleep. No one wants to film this.

The residents look like they could’ve all been in school together except for one. Number Four is older than her neighbours by a couple of decades. She owns while the others rent. The patio of her ground-floor apartment has a bistro-style table and chairs surrounded by carefully arranged potted plants; most everyone else’s is used to store bikes or not at all. Last Saturday night, she threatened to report Number Seventeen’s house party to the Gardaí for breaching restrictions unless it ended right now, and when it didn’t she stayed true to her word. She is a glamorous woman, usually well dressed and still well preserved, but this morning she is unkempt and barefaced, dressed in a pair of baby-pink cotton pyjama bottoms and a padded winter jacket that swings open as she strides across the courtyard.

She is also the only one who knows the code that silences the fire alarm. It went off five minutes ago – that’s what has woken them – and the residents assume they have her to thank for taking care of it.

There has never been a fire here but, in the last few weeks, three fire alarms – four if you count this one. The residents have complained repeatedly to the management company that the system is just too sensitive, that it must be reacting to burnt toast and people who smoke cigarettes without cracking a window, but in turn the management blame them for triggering it. The noise no longer signals danger but interruption, and when it went off a few minutes ago they all did what they usually do: went outside, on to their balconies and terraces, to see what they could see, to check for flames or smoke, not expecting any and finding none.

But this time there was something unexpected, something interesting: two uniformed Gardaí standing in the middle of the courtyard, looking around.

So they stayed out there, watching and wondering.

The woman from number four stands with the Gardaí while remaining the regulation six feet away. She’s pointing at one of the ground-floor apartments – the one right in the corner, at one end of the complex’s U-shape. They have little patios instead of balconies, marked off with open railings instead of solid glass perimeters. No one is on that patio. Its sliding door is closed. But from some vantage points, the glowing orb of the living-room’s ceiling light is visible through the thin grey curtains.

What’s going on?

Whose apartment is that?

Nobody knows. The Crossings is a relatively new complex and interactions are mostly limited to pleasantries exchanged at the letterboxes, the bins, the car park. Sheepish smiles during that window on Friday and Saturday evenings when it seems like everyone is going down to the main entrance to meet their food-delivery guy at the same time. The residents are used to living above and below and beside other people’s entire lives while pretending to be utterly unaware of them; hearing each other’s TVs and smelling each other’s cooking but never learning each other’s names.

Even in these last few weeks, when they’ve all been at home all day every day, they’ve studiously avoided acknowledging each other when they take to the outside spaces – the balconies, the terraces, the shared courtyard – in an effort to maintain some pretence of privacy, to preserve it. The crisis-induced camaraderie they’ve been watching in unsteady, narrowly framed short videos online – someone calling bingo numbers through a megaphone at a block of flats; a film projected on to the side of a house so a cul-desac of homes can have a collective movie-night from their driveways; nightly rituals of hopeful, enthusiastic hand-clapping – never really took hold here. They have kept their distance in more ways than one. No one wants to have to deal with a familiarity hangover when normal life returns, which they are all still under the impression will happen soon. A government announcement is due later today.

One of the guards twists his head around and looks up at them, these nosy neighbours. He pulls his face mask down with a blue-gloved hand, revealing pudgy cheeks at odds with a weedy body. They say that the Gardaí looking young is a sure sign you’re getting older, but this one actually is young, mid-twenties at the most, with a sheen of sweat glistening beneath his hairline.

‘False alarm,’ he calls out, waving. ‘You can go on back inside.’

As if any of them are standing there waiting to see a fire.

When nobody moves he shouts, ‘Go on,’ louder and firmer.

One by one, the residents slowly retreat into their apartments because none of them want to be pegged as rubberneckers, even though that’s exactly what they are. This is the only interesting thing that has happened here in weeks – if you discount the fire alarms, it’s the only thing that’s happened.

Are they really expected not to look?

Most of them leave their sliding doors open and elect to drink their morning coffees just on the other side, so they can see without being seen. The couples mutter to each other that, really, they have a right to know what’s going on. They live here, after all. The solo occupants wonder if there’s been a burglary or maybe even something worse, like an attack, and if something happened to them now, with things the way they are, how long would it be before anyone noticed, before anyone found them?

This apartment complex is not far from Dublin’s city centre. Before all this started it was buttressed by a near-constant soundtrack of engine noise, squealing brakes and car horns coming from the busy road that runs alongside. But in these last few weeks the city has slowed down, emptied out and shut down, in that order, and, occasional false fire alarms aside, the loudest noise lately has been the birdsong.

Now, the sound of approaching sirens feels like a violence.

56 DAYS AGO

‘Go ahead,’ are the first words he ever says to her.

They are both on the cusp of joining the queue for the self-service checkouts in Tesco. It’s Friday lunchtime and her fifth time this week coming in for yet another unimaginative meal deal: a colourless sandwich, a plastic bag of apple slices and a bottle of water, which she’s just noticed is the type with the sickly-sweet fruit flavour added. This realisation has stopped her in her tracks, paused by a stack of Easter eggs (Easter? Already?) and wondering if she can be bothered to go back and change it when she almost certainly won’t drink it anyway.

That’s when she looks up and sees him, politely waiting for her to make her move, leaving a space for her to join the queue ahead of him.

He’s taller than her by some margin. Looks about the same age. Neither muscular nor soft, but solid. His dark hair is thick and messy, but she has no doubt it took forever to pomade into submission, to perfect. He wears a blue suit with a navy tie and a light blue shirt underneath, but the sleeves of the jacket are creased with strain, the shoulders bunched, and the back of the tie hangs longer than the front. The top button of his shirt is open, the collar slightly askew, the tie pulled off-centre. He looks a little red in the face, his cheeks pink above patchy stubble.

And he’s so attractive that she knows instantly the world he lives in is not the same one in which she does, that he can’t possibly experience it the same way. A face like that affords a different kind of existence, one in which you arrive into every situation with some degree of pre-approval. But you don’t know it, don’t realise that you’re being ushered into the Priority lane of life every single day.

She wonders what that does to a person.

There’s an intensity to him, too, something simmering just beneath the surface. She imagines for him a whole life. He’s a man who works hard and plays harder. Who has a circle of friends he calls exclusively by inexplicable nicknames while they sit around a table in the pub necking pints and watching The Match. Who runs purely to run off bad calories. Who has someone somewhere that knows a completely different version of him, someone he is unexpectedly and devotedly tender to, who he only ever looks at with kind eyes.

‘It’s okay,’ she says, waving the bottle of water, starting to move away. ‘I’ve just realised I’ve got the wrong one.’ She turns and heads back towards the fridges, feeling his eyes on her as she walks away.

And the beat of her own heart, pulsing with promise.

_____

The second thing he says to her is, ‘Nice bag.’

She has just come out of the supermarket, on to the street, and doesn’t know who’s talking or if they’re talking to her.

When she turns towards the voice she sees him standing in the next doorway, looking right at her. The sandwich he’s just bought is tucked under his arm, getting squished by the pressure. There’s the hint of a grin on his face, tinged with something else she can’t readily identify.

She stops. ‘My …?’

‘Your bag,’ he says, pointing.

He means the little canvas tote she’s put her purchases in. He must do because her handbag is across her body and resting on her other hip, the one he can’t see from where he’s standing.

The tote is blue and has a Space Shuttle on it, piggybacking on an aeroplane as it flies over the skyscrapers of Manhattan.

She lifts and looks at it, then back at him.

‘Thanks,’ she says. ‘It’s from the Intrepid. It’s a museum in—’

‘New York,’ he finishes. ‘The one on the aircraft carrier, right?’ He says this not with smug knowingness but endearing enthusiasm. ‘Have you been?’

‘Yeah.’ She doesn’t want to sound like she’s too impressed with herself, so she adds, ‘Once.’

‘Was it good?’

She hesitates, because this is it. This is where she makes her choice.

People think the decisions you make that change the course of your life are the big ones. Marriage proposals. House moves. Job applications. But she knows it’s the little ones, the tiny moments, that really plot the course. Moments like this.

Her options:

Say something short and flippant, move on, end this now.

Or say something that prolongs this, stay longer, invite more, open a door.

She keeps a screenshot on her phone of a quote by, supposedly, Abraham Lincoln: Discipline is choosing between what you want now and what you want the most. Maybe that’s true, but discipline has never been her problem. It’s fear she struggles with. She thinks courage might be choosing between what you want now and what you want the most, because what she wants now is to walk away, to shut this down, to close the doors. To retreat. To stay in the place where she feels safe and secure.

But what she wants the most is to be able to live a full life, even if the expansion comes with pain and risk and fear, even if it means crossing a minefield first.

This one, maybe.

Ciara grips the handles of the tote and imagines her future self standing behind her, pressing her hands into her back, pushing, whispering, Do it. Go for it. Make this happen. She ignores the heat rising inside her, her body’s alarm. She reminds herself that this isn’t a big deal, that this is just a conversation, that men and women do this all day, every day, all over the world—

‘Yeah,’ she says. ‘But not as good as Kennedy Space Center.’

He blinks in surprise.

He straightens up and steps closer.

Moving aside so a woman pushing a double-buggy can get past, she takes a step closer to him, too.

‘You know,’ he says, ‘I’ve never met someone who can name all five Space Shuttles.’

‘And I still haven’t met someone who knows there are six.’

She bites her lip as every blood cell in her body makes a mad dash for her cheeks. What the hell did she have to go and say that for? What was she thinking?

‘Six?’ he says.

She’s already ruined it.

So she might as well make sure she has.

‘There was Challenger,’ she says to the crack in the pavement by her right foot, ‘lost 28 January 1986 during launch. Columbia, lost 1 February 2003 during re-entry. Atlantis, Endeavour and Discovery are all on display – Atlantis is the one in Kennedy Space Center. But there was also Enterprise, the test vehicle. It flew, although never in space. It didn’t have a heat shield or engines, but it was the first Orbiter. Technically. Which is actually what people mean when they say, “Space Shuttle”, usually. They mean the orbiter itself. The rest is just rockets. And Enterprise is the one that’s at the Intrepid.’

A beat of excruciating silence passes.

She forces herself to lift her head and meet his eye, lips parting to mumble some lie about needing to get back to work, foot lifting in readiness for scurrying away from this absolute disaster, but then he says—

‘I was going to go get a coffee. Can I buy you one too?’

There are numerous coffee options on this street and the vast majority of them come served with a side of serious notions. There’s the café that roasts its own beans and makes you wait five minutes for a simple filter coffee that only comes in one size served lukewarm. It’s right next to the place that has spelled its name wrong and, inexplicably, with a forward slash: KAPH/A. The most popular spot seems to be a little vintage van in the service-station forecourt, the one with a hatch whose chalk-drawn menu lists not coffee blends but levels of depleted wakefulness: Fading, Sleepy, Snoring.

Ciara is relieved when he directs her past all of them and into the soulless outlet of a bland coffee chain instead.

‘Is this okay?’ he asks as he holds the door open for her.

‘This is great.’ She steps inside, turning to talk to him over her shoulder. ‘I like my coffee served in a bucket at a reasonable price, so …’

‘I’ve passed the first test, is what you’re saying.’

He winks at her and she laughs, hoping it didn’t come out sounding like a nervous one, although she is nervous.

Because of the implication in the word first.

Because she has to pass this test too.

Because this is already the weight of one whole foot on the edge of the minefield and she has no idea how wide it is, how long it will take her to get all the way across, how long it will be before she feels safe and comfortable and secure.

In the minute it took to walk here, he has told her his name is Oliver and that he works for a firm of architects who have the top floor of the large office building across the street. He is not an architect, though, but something called an architectural technologist. He explained it by saying that architects design the buildings and then architectural technologists figure out how they’re going to actually build them. He tried to dissuade her of the idea that it’s any bit as interesting as it sounds, promising that, in reality, it’s mostly spreadsheets and emails. When she asked him if it’s what he always wanted to do, he said yes, once he’d come to terms with the fact that he was never going to be astronaut.

Then he asked her what she does.

She explained that after her astronaut dreams fell by the wayside, she ended up working for a tech company who just happen to have one of their European hubs in a sprawling complex of glittering glass-and-steel office buildings a few minutes’ away from where they stand. She held up her bright blue lanyard and he read her name off it and said, ‘Nice to meet you, Ciara,’ and she said, ‘Nice to meet you, too.’

Now, at the counter in the coffee shop, she says she’ll have a cappuccino. He orders two of them, both large.

‘To go?’ he suggests. ‘We might snag a seat by the canal.’

‘Sounds good to me.’

She tries not to look too pleased that he wants to prolong this, whatever this is, into drinking the coffees as well.

She goes to wait at the end of the counter and watches him pay at the till with a crisp ten-euro note. She sees the barista – a teenager; she can’t be more than seventeen or eighteen – steal glances at him whenever she thinks he’s looking at something else. She wonders if he’s aware of that and, if he is, what it feels like. (Approval or scrutiny?) She traces the lines of his body as suggested by his clothes and wonders what it would feel like to know the skin underneath, if she will know it, if this really is the start of something or just an anomaly.

She imagines those arms around her, the strength in them, how it would feel to be held by him.

Then she tries not to.

She doesn’t put sugar in her cappuccino, even though she normally does, and she thinks to herself, If this becomes something, I’ll never be able to put sugar in my coffee now.

The sun has been appearing and disappearing all day; when they go back outside, they’re met with mostly blue sky. The canal bank is busy with lunching office workers, but they find a spot on the wall by the service station, near the lock.

They settle down.

He prises the lid off his cappuccino to take a sip. She resists the urge to tell him that this will make it go cold faster but lets him know when he’s managed to collect a crescent of foam on his upper lip.

‘So,’ he says, ‘Kennedy Space Center.’

‘What about it?’

‘Tell me things that will make me very jealous that you’ve been there.’

She describes the bus tour that takes you around the launch pads, the Vehicle Assembly Building and the famous blue clock that you see counting down to launch on TV. Tells him about the IMAX cinema and the Rocket Garden. The ‘ride’ where they make you feel like you’re on a launching Space Shuttle, how they tilt it straight up so you’re lying on your back and then forward a bit too much so you start to slide out of your seat in a clever approximation of zero-G. The Apollo Center where you get to see an actual Saturn V rocket, lying on its side at ceiling-height above the floor. The shuttle Atlantis, a spaceship that has actually been in space, on magnificent display.

‘It’s revealed to you,’ she says. ‘Unexpectedly. A surprise. You’re herded into this big, dark room to watch a video about the Shuttle programme and then, at the end, the screen slides up and reveals the Shuttle just … Just there, in all its glory, right in front of you. With the cargo bay doors open and at an angle so it actually looks like it’s flying through space. It’s amazing. People actually gasped. After I’d walked around it and taken all my pictures and read all the exhibits and stuff, I went back to where I’d come in and I waited for the screen to go up so I could watch other people’s faces, so I could see their reactions, and it was …’ She sees what looks to her like his bemused expression and panics. ‘It’s just that I wanted to go for so long – since I was a child, really – so it was a bit like, I don’t know … Walking around a dream.’

A long moment passes.

Then he says, ‘I really want to go.’

Relief.

‘You should,’ she says.

‘Thing is, I hate the heat.’

‘Don’t let that stop you. It’s all ice-cold air-conditioning and misting machines. Plus, it’s not always hot and steamy in Florida. I went in March and it was actually quite nice.’

‘Was this a girls’ trip or …?’

She pretends not to have noticed that he is fishing for information and he pretends not to have noticed her noticing but pretending not to.

‘Work, primarily,’ she says. ‘A tech conference in Orlando. So I was able to slip away and go geek-out without an audience, thankfully.’

Ciara turns to look out at the canal. It is beautiful up close, she’ll give it that. The water is still, the reflections in it defined. The weather is pleasant enough for people to sit on the benches in their coats but not to show skin or plonk down on the grass. A steady stream of office workers and lunchtime runners crosses back and forth on the narrow planks of the lock right by a sign that warns of Deep Water. Watching them makes her nervous, and she looks down at her coffee instead.

She can feel his eyes on her.

‘Cork, right?’ he says.

‘Originally. We moved to the Isle of Man when I was seven.’

‘The Isle of Man? I don’t think I’ve met anyone who lived there before.’

She smiles. ‘Well, I can assure you, thousands of people do. My dad grew up there and thought I’d want to, too.’

‘Did you?’

‘Not at the time, no. But it was all right in the end. What about you?’

‘Kilkenny,’ he says, ‘but we moved around a lot.’

‘How long have you been in Dublin?’

‘What’s it now’ – he makes a show of thinking about it – ‘six weeks?’

‘Six weeks?’

‘Well, six and a half. I arrived on a Tuesday.’

‘Where were you seven weeks ago?’

‘London,’ he says. ‘And you?’

‘How long am I in Dublin?’ She pretends to think, mimicking him from a moment ago. ‘Well, next Monday it’ll be, ah … seven days.’

‘Seven days? And here was I thinking I was the newbie.’

She laughs. ‘Nope, I win that game.’

‘Where were you before?’

‘Cork, since I finished college. I went to Swansea. Not-atall-notable member of the Class of 2017, here.’

His face can’t hide the fact that he’s trying to do the maths. She almost offers, ‘I’m twenty-five,’ but that’s not how this game is played.

She doesn’t know much but she knows that.

‘What about you?’ she asks. ‘Where did you go?’

‘Newcastle,’ he says flatly.

Ciara senses that something has changed, that she’s lost him somewhere along the line. What was it that did it? She has no clue, but knows she can look forward to lying awake in the dark and wondering for days to come, forensically analysing everything she said and then re-analysing it, trying to find the wrong thing, the mistake, the regret.

‘I’m going to be late back.’ He says this a fraction of a second before he shakes his wrist and looks at his watch.

He stands up then and, not knowing quite what to do, she does as well.

‘Yeah, I better go, too,’ she lies. ‘Well … Thanks for the coffee.’

He chews on his bottom lip, as if trying to decide something.

‘Look,’ he starts, ‘I was going to go see that new Apollo documentary. On Monday. Night. They’re showing it at this tiny cinema in town. Maybe – if you wanted to – we could, um, we could go see it together?’

She opens her mouth to respond but is so taken aback by this invite that she delays while her brain tries to catch up with this change of course, and into this pause he jumps with an embarrassed, ‘God, I’m so shit at this.’

This.

She wants to tell him that no, he’s not, and she doesn’t believe for a second that he thinks he is, but mostly she doesn’t want to have to respond to him referring to this as a this because what if he didn’t mean what she hopes he did?

‘That sounds great.’ She flashes her most reassuring smile. ‘Sure. Yeah.’

He says he will book the tickets. They arrange to meet outside the building where he works at half-five on Monday evening. He gives her his phone number in case there’s any last-minute problems and she sends him a text message so he has hers. They walk back together as far as his office, then wave each other goodbye. She doesn’t take a deep breath until she’s turned her back to him.

And so it begins.

TODAY

Technically speaking it’s Friday-morning rush-hour, but Lee has the roads to herself. She makes it to Kimmage in no time at all and lucks into a parking space right outside the house. The street is still, its residents robbed of all their reasons to get up early, to start their days somewhere further away than another room of their home. There’s been no commutes for weeks now, no school runs, no tourists arriving in or heading off. Even the plague of early-morning joggers from the start of lockdown seems to have tapered off.

The nation’s collective motivation to make the most of this is waning, that much is obvious. She wonders how many sourdough starters have been, by now, unceremoniously fecked in the bin.

Lee rolls down the driver’s-side window and settles in to drink her coffee. The coffee that she had to watch someone make with gloved hands and theatrical caution as if it wasn’t a cappuccino they were making but a bomb, whose cost included the forced sanitising of her already dry and chapped hands before and after collecting, that only has two sugars instead of her preferred three because now the barista has to put them in for you and she was too embarrassed to ask for that many, the coffee that she’d literally risked life and limb to get.

She refuses to let it go cold after all that.

With her free hand, Lee pulls down the visor and inspects the wedge of her own face she can see in the little mirror there. She seriously needed her roots done before they shut down the salons; the brunette is practically down to her ears and in this natural light, appears to end in a blunt line. Like every other morning she’s left home in a hurry, hair still wet, and now it’s drying into her trademark helmet of electrified frizz. She thought she had thrown some make-up on but it has evidently managed to clean itself off in the last half-hour. The smudge of tan foundation on the collar of her white shirt is the only evidence it was ever there at all.

She really needs to get her shit together.

There’s a part of her that wishes she had a different job, the kind that’s normally done from a stationary desk in an office and can now be – now must be – done from home. She’s found herself fantasising about being one of those women who live alone, temporarily free from all exhausting social expectations, finally able to establish a skincare routine and a yoga practice with that one on YouTube that everyone raves about; to crack the spine on the healthy-food cookbooks her family have been pointedly gifting her for years; to go for long walks along beaches and clifftops and through woodland, the kind of treks that leave you pink-cheeked and aching with smug self-satisfaction and reconnected with nature (although Lee would have to connect with it first); emerging from the other end of this lockdown a shinier, smoother, brighter version of herself, Lee 2.0.

And honestly, she’d settle for painting her living room and losing half a stone.

But there’s no beaches or clifftops or woodland within a two-kilometre radius of her front door, the hardware shops are closed and there is no lockdown for her. She’s still at bloody work.

On the passenger seat, her phone beeps with a new text message.

She knows damn well who it is before a glance at the phone’s screen confirms it: KARLY.

Detective Sergeant Karl Connolly. She’d added the ‘Y’ to annoy him and it had worked a treat.

The message says: BTA?

Lee doesn’t pick up the phone. She takes another long, slow sip of her coffee. But when her phone beeps for a second time, she curses, shoves the coffee into the cup holder between the front seats and climbs out of the car.

The house looks exactly as it did the only other time she was here. A narrow, two-storey red-brick terrace that, were it in mint condition, would easily sell for half a million around these parts. But this one is crumbling. The bricks need cleaning and the roof tiles repairing. The window frames are wooden and rotting in the corners. Paint is enthusiastically peeling off the front door. A skip is parked in the driveway, half-full with seventies furniture and broken things.

It was there the last time, too. Lee distinctly remembers seeing the cracked salmon-coloured bathroom sink because her parents had one just like it. This house was a work-inprogress without much progress, and now, like everything else, its renovation is on pause.

She should ring the doorbell, announce her presence. Should. But she isn’t in a charitable mood this morning. Instead, she goes to the front window and touches her fingers to the underside of its cement sill, feeling for the hollow she’s been told is there. She quickly finds it – and the pointy end of the key that’s inside.

Stealthily, she lets herself in through the front door.

The house is still, the air a little musty, stale. There are no carpets on the ground floor – only bare, dusty floorboards – but a heinous swirl of shit-brown and bright orange clings to the staircase. She starts up it, moving slowly and carefully, testing her weight on each step so as to avoid a telltale creak.

There’s no noise in the house, no sounds from upstairs, but the quiet has a deliberateness to it.

Someone is maintaining it.

He’s not asleep, then, but awake and waiting for her.

Maybe he even heard her come in.

Lee reaches the landing. Four doors lead off it. One is open on to a room filled with building materials: a workbench, some sort of sanding machine with its electrical cord wrapped around itself, boxes marked CRACKLED WHITE 7.5 x 4. Another is showing her a bathroom that appears to be in mid-update. A third looks like it can only be hiding a boiler. The fourth then, to the front of the house, is the master bedroom.

That door has been pulled closed but isn’t fully shut.

She pauses outside, then kicks it open with such force that it opens all the way, hitting the wall behind it with a thunder clap.

The first thing she sees is the wallpaper. It must have been bought on the same shopping trip that found the diarrhoea-after-carrots-carpet on the stairs. It’s an acid trip of bright blue paisley, and it hurts her eyes.

Then the smell hits: sweat and sex and alcohol, trapped and cooking in the room’s warm air.

She should’ve worn a mask, she thinks now. God only knows what’s floating around in here.

‘Well,’ she says, ‘what seems to be the problem?’

Karl is lying on the bed, presumably naked under the fitted sheet that he’s somehow managed to lift off the bottom corners of the mattress and drape across his lower half.

This must have taken some doing seeing as both his arms are outstretched, hands higher than his shoulders, like Christ on the cross.

Only Karl’s wrists aren’t nailed to the headboard, but handcuffed to it.

‘Two sets?’ Lee frowns. ‘Where’d you get the second lot?’

‘Go on,’ Karl groans. ‘Lap it up.’

‘Oh, I fully intend to.’

‘You know, I could’ve sworn I heard you pull up outside five minutes ago.’

‘How long have you been like this?’ Lee asks.

‘All bloody night.’

‘Did you sleep?’

Karl attempts a shrug, then winces at the pain this move causes him. ‘Dozed. Hey, do you think you could free me before this interrogation continues? I’d get better treatment in the cells.’

‘How did you text me if—’

‘Siri.’

Karl nods towards his phone, lying on the bedside table.

‘She got a letter wrong in the last one,’ Lee says.

‘You take your time.’

‘Look, you’re lucky I came at all. And I’m just dying to find out what Plan B was.’

‘I know this is the best thing that’s ever happened to you, Lee, but I can’t actually feel my hands here.’

She indulges in an eye-roll before relenting, fishing her keys from her trouser pocket and moving towards the bed.

‘Whatever you do,’ she says, ‘hang on to that fitted sheet.’

Karl scoffs. ‘Like you wouldn’t love a look.’

‘I’ve had a look, remember? Although I barely do. Wasn’t particularly memorable.’ She pulls Karl’s right wrist towards her – he yelps in pain – and bends to work the small key into the cuff’s lock. ‘So where is she, then? Who is she?’

‘Fuck knows. On both counts.’

‘Ever the romantic, eh, Karl?’

‘I’ve seen you open cuffs. What the hell is taking so long this—’

The key clicks in the lock and Lee ratchets the cuff open enough to slide it off Karl’s wrist.

His arm drops on to the bed like a dead weight that’s been cleanly detached from his body. Gingerly, he tries to bend it but only manages a few degrees before spitting out a string of curse words, closing his eyes and giving up.

‘Are the keys even here?’ Lee asks, moving to the other side of the bed to work on the other set.

‘Took them with her. Told me she was going to flush them down the toilet. Well, joke’s on her because it isn’t even connected.’

Lee makes a face. ‘Where are you …?’

‘Porta Potti. Out by the shed.’

‘Did she know that before she came back here?’

‘No, and she came over.’ He grins. ‘And she came—’

‘If you finish that sentence, I swear to God, I’m locking you back up.’

When the second set is removed, Karl lurches forward, wincing as he tries to bring his arms closer to his body, increasing both the vehemence and the range of his muttered swears with every inch.

‘Christ. My arms feel like they’re on fire.’

‘Well, let that be a lesson to you.’ Lee steps back from the bed. ‘And she lives less than 2K away, I suppose, this mysterious, angry woman?’

‘Don’t know.’ He shrugs. ‘Didn’t ask.’

‘Karl, for feck’s sake. You will end up on Snapchat at the rate you’re going and even I won’t be able to save your arse then.’

A relatively new phenomenon: members of the Gardaí ending up named and shamed on social media. The last one that got the attention of the higher-ups was a video clip from a house party hosted by a known drug-dealer, at which a Garda currently stationed in the district was a seemingly enthusiastic and friendly guest.

‘I didn’t tell her I was a guard,’ Karl says, as if such a thing was preposterous even though he’d managed to get locked in two sets of handcuffs during a sex game with a stranger whose visit to his house also constituted a breach of the country’s current COVID-19 restrictions.

‘Where did you tell her you got the handcuffs from, then?’

‘I didn’t. We weren’t doing much talking, Lee, if you know what I—’

‘Do even less of it now.’

Lee looks down at the second set of cuffs, which she’s still holding, and sees a mark in blue paint near the lock and two initials scratched into the metal by the hinge: E.M.

She shakes her head. ‘Seriously, Karl?’

‘What?’

He looks up at her, at the cuffs in her hand, back at her face. He’s managed to bring his arms into his lap but is rigid in that position, like his entire upper body is encased in an invisible plaster cast.

‘Don’t you “What?” me. You know what. These are Eddie’s. Blue paint, initials. That’s what it said on the report the poor guy had to file because he thought he’d lost them.’

‘He did lose them. He forgot to take them off that coked-up eejit we hauled out of the house party in Trinity Hall a few weeks back.’

‘You know he’s already on thin ice,’ Lee says.

‘And you know why: he’s shit.’

‘It wouldn’t occur to you to help the guy out a little bit?’

‘I am helping him out,’ Karl says. ‘Out of the force, because he doesn’t belong in it.’

Lee’s phone starts to ring.

The number on the screen belongs to the station on Sundrive Road, which instantly piques her interest.

Why would someone at the station be calling, when she and Karl aren’t due on shift for another half an hour?

And why not just hail them on the radio?

‘Lee,’ a male voice says when she answers. ‘We’ve got a problem.’ She recognises it as belonging to Stephen, one of the lads on the unit. ‘Can you talk?’

‘Yeah,’ she says. ‘Go on.’

‘A call came in at the crack of dawn from our friend over at The Crossings, the one-woman residents’ association. We assumed it was just going to be another waste of everyone’s time, so we, ah …’ He clears his throat. ‘Well, we sent Ant and Dec.’

‘You did what?’

Since the unit’s two newest members look like Confirmation boys and one of them is called Declan, they’d instantly earned a nickname inspired by the eternally youthful duo of TV presenters.

‘We didn’t think it was going to be anything,’ Stephen says. ‘Same one has been calling every other day to tell us her neighbours have friends over.’

‘And what was it this time?’

‘There’s a body in one of the ground-floor apartments. And not a pyjamas-in-their-own-bed kind.’

‘Fuck,’ Lee says.

‘Lucky for us, she called an ambulance too and Paul Philips was driving it. As soon as he arrived on scene, he realised what it was and told Ant and Dec that they’d better call Mummy and Daddy.’

Two green bananas, alone together at a crime scene, with no senior officer to tell them which is their ass and which is their elbow. The first members on scene in a potential murder investigation. Lee knows nothing more than this, but she can already see any hope of a successful prosecution getting further away with each passing, inexperienced second.

She pinches the bridge of her nose, closes her eyes.

When she opens them again, she sees Karl looking at her questioningly.

‘I know this is bad,’ Stephen says in her ear, ‘but we didn’t think—’

‘We’ll talk about the not-thinking later. I’m with Karl, we’ll go straight there now. Text me the full address. Send me a few cars. Tech Bureau and pathologist, too. If anyone else gets there before us, tell them to set up the cordon. No one leaves. Then call Ant and Dec back and tell them one of them needs to stand outside the apartment door and the other one needs to meet me outside the building and they are not to so much as breathe until I get there. Keep this off the air until you hear from me again. And start praying that this gets un-fucked up before the Super gets wind of it. Got all that?’

‘Got it.’

After she ends the call, Lee throws Eddie’s cuffs on to the bed in a high arc, hitting Karl square between the legs with their full weight and then some, sending him into a spasm of new pain.

She doesn’t wait for him to recover.

‘Get dressed,’ she says. ‘We need to go. Now.’

53 DAYS AGO

Him not being there, not waiting for her outside his office building as arranged, is not the worst-case scenario. The worse-case scenario is him not being there but somewhere else that offers a view of that spot, from where he can watch her waiting for him like a fool. To avoid this, Ciara arrives twenty minutes early and buys a coffee in the Starbucks just around the corner, which she sips at one of their outdoor tables with her eye on the time. When it gets to the half-hour, she waits a minute more before leaving, crunching on a chalky mint to ward off coffee-breath.

He is the first thing she sees when she turns on to the main street. There, where he said he’d be, waiting for her.

Relief floods her veins.

He turns and waves. She waves back, doing her best to look like she’s dashed here straight from the office.

He is dressed as he was on Friday; men’s suits are indistinguishable to her, for the most part, but it could be a different one. The tie is a different colour, anyway. The thick strap of a beat-up leather messenger bag rests across his body. He has no coat or jacket, even though she is glad of hers already and there’s a whole night to get through yet. She has gone for standard work clothes, but on a day when she is making an effort: a black shirt dress over black boots and tights, her trusty green winter coat, black handbag.

It’s odd to see him now, smiling and coming towards her, when they have so recently been strangers and he looks the way he does. She has managed to forget, in the seventy-odd hours since she last saw him, how striking he is.

What it feels like to look into those eyes.

To have them be looking back at you.

He is stretching out an arm to greet her with a hug before she has a chance to worry about how they will greet each other and what acute awkwardness might ensue if it turns out they have different expectations. The hug is loose and polite, one-armed on either side, not at all intimate. But she gets a whiff of whatever scent he’s sprayed on himself – in the last five minutes, going by its potency – and to be so close to him, to touch him and be touched by him, even momentarily, is heady and disorientating. Her body’s reaction takes her aback and she doesn’t hear what he says immediately after they break away and turn to walk side by side in the direction of town, so distracted is she by the fading heat of the contact.

‘Hmm?’ she says.

‘I said maybe we shouldn’t have done that. You know, hugged.’ He sticks his hands in his pockets. ‘You heard they cancelled the parade? Although it’s probably for the best. It’s all tourists at that thing anyway. The only time I’ve ever done anything for it was when I was abroad.’

They’ve cancelled the St Patrick’s Day parade. That’s what he’s talking about.

As they walk side by side up the street, she sees women walking in the opposite direction steal glances at him as they pass. This makes her feel both completely invisible and superior to them at the same time.

These women haven’t even noticed she’s there too, but she’s the one walking with him. It’s a weird brand of pride.

‘Same here,’ she says.

He tells her that when he was in London, Patrick’s Day was one of the biggest nights of the year. A ticketed event at an Irish pub packed to the rafters, leprechaun outfits, drinking green beer – all things they wouldn’t be caught dead doing at home. One of his top ten hangovers ever. His brother had been visiting, which didn’t help.

He asks her if she has siblings.

‘No, I’m that rare specimen,’ she says, ‘the Irish only child.’

‘In the same realm as a unicorn sighting.’

‘Leprechaun, surely?’ She smiles. ‘But yeah. Is it just you and your brother or …?’

‘Just us.’

‘Is he here?’

‘He lives in Perth now. Has done for a while. Got the whole set-up out there: mortgage, kids, pensionable job.’ A pause. ‘I can’t see him ever coming back. He loves the weather.’

They cross the road to Baggot Street Bridge.

‘Favourite movie?’ she asks.

‘I think his is the second Godfather.’

She laughs. ‘And yours?’

‘Jurassic Park.’

‘I don’t have one,’ she says, ‘before you ask. I just don’t know how people can narrow it down.’

‘I feel that way about food.’

‘Well, there, I can do categories. Favourite cocktail, favourite pizza, favourite sandwich – but that’s as far as I go.’

‘Go on then.’

‘Sandwich is toasted cheese,’ she says. ‘Toasted with mayonnaise on the outside. Has to be mayonnaise. Not butter. That’s the best way to get it golden. Pizza is roast chicken strips and red onion. Can’t beat it if the ratio is right. Cocktail … Well, I’m not a big drinker, really, but I do like a French 75.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Gin and lemon juice, little bit of sugar syrup, topped with prosecco. Or champagne, depending on how much it costs. It’s basically adult lemonade.’

‘Where does a good one?’

‘Oh,’ she says, ‘I’m nowhere near discerning enough to know that. If it comes in a flute and tastes a bit fizzy, it’ll do me. And to be honest, the flute isn’t a deal-breaker.’

‘And you’ve only been here a week …’

‘And I’ve only been here a week.’

‘Well,’ he says, stopping to bow slightly and roll his hand towards her like the maître d’ of a posh restaurant, ‘I’ve been here six weeks so I’m practically a Dubliner now—’

‘Certifiable, surely.’

‘—and so I know where we can get a nice cocktail. It’s even near the cinema.’ He holds out an elbow so she can curl her arm around his. ‘Shall we?’

They talk about work and TV shows and whether or not more things will be cancelled because of this faraway flu, and stroll through a city that feels quiet even for a Monday night. He tells her that a lot of the multinationals have their people working from home already. She says she knows and then he rolls his eyes at his forgetting that she works for one of them. She says she’ll be shocked if she’s still in the office at the end of the week, that they’re all just waiting for an official announcement. A few departments have already made the move. She thinks she can do her job just as well at home. She explains that the problem is they have thousands of workers sitting within feet of one another in a confined space, breathing recirculated air and using the same bathrooms, teaspoons, etc., and every day of the week dozens of them are coming into work fresh from trips to other facilities and offices abroad, having travelled through airports and squeezed themselves into crowded aeroplanes. It’s the potential threat they’re acting on, not the reality. At least for now. Someone got the measles last year and it was the same sort of thing – not because the overlords are humanitarians, but because workers being home sick affects the bottom line. Better to have them home working for a while, even if it ends up being a total overreaction.

‘Here we are,’ he announces.

While she was nattering on, he’s steered her off Grafton Street and now they are standing in front of a fancy hotel. The smooth, dark gloss of its first-floor bay windows promise low, warm light inside. Lush green foliage drips from the portico. Through gold-edged double glass doors she can see an imposing staircase covered in plush carpeting. A uniformed doorman in gloves and a hat stands sentry just outside. International flags blow gently in the breeze above polished gold lettering that spells out the hotel’s name: THE WESTBURY.

She’s heard of it but didn’t know it was here, didn’t know it was down this street, in this building that’s only ever been in her peripheral vision as she walked past.

‘The bar does amazing cocktails,’ he says.

‘Great.’

She tries to sound like she means it, like this is great, but her eyes are on the doorman. He’s just a bouncer in better shoes. She is hyper-aware of the scuffed toes of her fake leather boots, the thin fabric of her dress and the bobbles of wool on the sleeves of her winter coat. The coat that was sold at a price that suggested you should be happy to get a month of wear out of it, the same one she’s wearing for the third winter in a row. If she had known this was where they’d be going, she would’ve worn something else. She might have even tried to stretch to buying something new.

She should have known. Of course Oliver is a man who goes to places like this, who assumes he is welcome in them – because he is. The face, the suit, the cool confidence. He strides right up to the door as if the doorman isn’t even there and this is, apparently, the way to do it. The doorman not only opens the door for them but greets them both with a wide smile.

Having disentangled their linked arms to walk inside, Oliver puts a hand against the small of her back as they ascend the stairs. He’s not steering her or claiming her, but reassuring her. She wonders if he can sense how uncomfortable she is.

Another staff member, a glossy brunette, greets them at a hostess stand and directs them into the bar. When she says, ‘Right this way,’ she says it to him from beneath a fluttering of long, dark eyelashes.

The bar is a feast of mirrored things and shiny edges, of crystal chandeliers and glasses, of plush leather upholstery and marbled surfaces. Hundreds of different coloured bottles line the wall behind the counter. The lighting, like the rest of the hotel, is low and warm. A real fire burns at one end. More uniformed staff stand waiting to tend to them.

It’s like a movie set and, for a moment, Ciara feels a little mesmerised.

The place is practically empty, with only a handful of patrons, who all sit around one table at one end, by the roaring fire. They are directed away from them to a cosy, circular booth at the other.

When prompted, she hands over her coat to be disappeared to some plush cloakroom and tries not to think about the hostess seeing the Primark printed on its tag. Then she chastises herself for thinking about that at all. Oliver gives the hostess his suit jacket without even looking at her.

They sit down.

He unbuttons his cuffs and starts to roll up his sleeves. His forearms are pale and covered in coarse, dark hair. He wears a silver watch that looks heavy.

‘So what do you think?’ he asks. He waves a hand to indicate that he’s asking about her thoughts on the bar.

‘Bit grubby, if I’m honest. They could really do with sprucing the place up a bit, couldn’t they?’

He grins. ‘You should see the bathrooms, they’re absolutely disgusting.’

‘Better or worse than those holes in the ground they have in France?’

‘You’ll wish you were in one of them.’

Their banter feels like rapid gun-fire and after each successful exchange, she feels a bit dizzy with relief, like she’s gone over the top in the trenches and made it to cover without taking a hit.

A waiter approaches them with two cocktail menus.

‘Ah, we’ll have two’ – Oliver looks to her – ‘what are they called?’

‘French 75s. Please.’

‘Excellent choice,’ the waiter says. ‘Will I leave the menus?’

‘Please do.’ She reaches to take one from him. ‘Thank you.’ And then, to Oliver, ‘Let’s see what else they’ve got in here …’

But what she’s really looking for is the price of the drinks they’ve just ordered. She flicks through, pretending to muse with deep interest over the other cocktail options. She tries not to react when she turns a page and sees it: the cocktails are €24. Each.

‘Speaking of bathrooms,’ Oliver says, sliding to move out of the booth. ‘I’ve drunk about a litre of coffee today, so …’

‘Don’t fall in the hole.’

‘If I’m not back in five minutes—’

‘Wait longer, I know.’

She watches his back disappear through the bar’s doors. Then she pulls her handbag on to her lap and starts fishing around in it for her wallet. She does a rough calculation of the creased notes inside: enough to cover the cost of two rounds of these drinks plus a cab home, just about.

He’ll probably pay. He’ll likely pay.

But still.

She slides two fingers into the little pocket attached to the bag’s lining and relaxes slightly when she feels the thin hardness of her debit card, the raised text on it against her fingers.

She’d rather not have to use it, but she can if need be.

She’ll figure something out.

They have just ordered a third round when he says, ‘You’re not going to believe this.’

Her cheeks feel warm, her limbs languid, her tongue loose. She’s not yet drunk but drunker than she expected she’d get, than she knows she should be. It’s because she didn’t have any lunch. Couldn’t have any; nerves had stolen her appetite. She pulls her glass of water closer and silently resolves to drink it all before she takes even one more sip of alcohol.

She says, ‘Try me.’

He shows her a flash of something on his phone. ‘The film started ten minutes ago.’

‘You’re joking.’

‘We could make a run for it. They’re probably still on trailers and it’s only a couple of minutes away.’

‘Would it be terrible—’ she starts at the exact same time he says, ‘Or we could just stay here.’

They both laugh.

‘I hate rushing,’ he says.

‘Me too.’

‘And I like drinking.’

‘Me too.’

‘And I like you.’

‘Well, I am very likeable.’

He laughs. He’s impressed with her.

After that quip, she’s a little impressed with herself.

‘So,’ she says, clearing her throat. She needs to change the subject, to give herself some time to come back from the tipsy cliff-edge. ‘Do you come here often?’

‘Oh, come on.’

‘I genuinely want to know.’

‘This is actually only my second time here,’ he admits. ‘And the other time was with work. I just …’ He pinches the stem of his glass and slides it back and forth a little until the liquid starts to slosh around inside. ‘I wanted to come back here with … Not work.’

‘Not work. Wow. I bet you say that to all the girls.’

‘Do you like it?’

Their eyes meet as he asks this and it occurs to her that up until now, practically sitting side by side, she hasn’t been making much eye contact with him at all.

It’s just as well because the way he’s looking at her now …

She never really understood the phrase piercing when applied to eyes, but that’s what his are. He’s not just looking at her but in her, it feels like, right through the thin veneer of this pretending. It’s as if he has X-ray vision that can effortlessly penetrate all the way to the real Ciara, the one who’s curled up and careful and desperately trying to protect herself from what it might feel like if this evening goes horribly wrong.

She looks away, back to her glass.

‘I do,’ she says. ‘I do like it. I mean … Look, it’s not really where I’d usually be, let’s put it that way.’ The alcohol fizzes in her bloodstream, disintegrating walls his gaze has been weakening all night. She can’t let them fall away completely, not on this, their very first date, but she can put her face to one of the gaps and speak to him across clear air without having to risk a step outside the boundary. ‘I can’t really afford to come to places like this, to be honest. Not on the regular, anyway. And if I’d known this is where we’d end up, I would’ve dressed differently. I was afraid the doorman was going to stop me and say, “Sorry, love. No Penneys apparel allowed inside.”’

‘He calls you love and says apparel? Who is this guy?’

She slaps him playfully on the forearm.

‘You know what I mean.’

‘For the record,’ he says, ‘I think you look lovely.’

She mumbles, ‘Thank you,’ to her glass.

‘It’s just a bit special, isn’t it?’

He could mean the bar. Or the drinks.

Or this night, with her in it.

‘Here’s what I like about this place.’ She’s careful to speak her words more slowly than she’s thinking them, distinctly pronouncing each one. Or so she hopes. ‘It’s hidden. It’s not a secret, but it’s not on show. You can’t know this is here when you walk past this building on the street, but come inside and turn a corner and it’s revealed to you, this beauty that’s been here all the time. Waiting. And I love that. I love discovering places like this because it makes me wonder about what else is inside all these buildings I walk past everyday. What else is just waiting to be discovered? There’s a whole hidden city. Several hidden cities. All hiding in plain sight in this one.’