Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

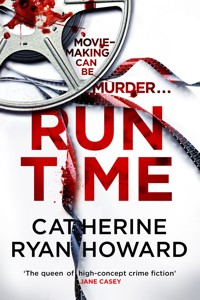

SHORTLISTED FOR THE IRISH BOOK AWARDS' CRIME FICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR _________________________________ *** A Top Ten Kindle Bestseller *** 'Pure nerve-shredding suspense from the first page to the last' Erin Kelly 'Blair Witch meets Fleabag ... pure mastery' Janice Hallett 'Dazzling'Riley Sager _________________________________ Movie-making can be murder. The project Final Draft, a psychological horror, being filmed at a house deep in a forest, miles from anywhere in the wintry wilds of West Cork. The lead Former soap-star Adele Rafferty has stepped in to replace the original actress at the very last minute. She can't help but hope that this opportunity will be her big break - and she knows she was lucky to get it, after what happened the last time she was on a set. The problem Something isn't quite right about Final Draft. When the strange goings-on in the script start to happen on set too, Adele begins to fear that the real horror lies off the page... _________________________________ 'A roller-coaster ride and fun in every sense, I loved it!'Andrea Mara 'Will have you glued to your sunbed ... insists on being read in one sitting' Gloss

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Catherine Ryan Howard

Distress Signals

The Liar’s Girl

Rewind

The Nothing Man

56 Days

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Catherine Ryan Howard, 2022

The moral right of Catherine Ryan Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 166 5Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 167 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 168 9

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk/corvus/

The road is narrow, the edges of it crumbling, as if losing its battle to hold the treeline back.

Donal is tense behind the wheel. Grip tight, back ramrod-straight, eyes fixed on the road surface illuminated by the beam of the headlights. The rental is a seven-seater Volvo that gave him pause when he saw it first and made him sweat nervously when he found he had to step up into it. He’s only ever driven his own succession of second-hand Nissan Micras, and only around and between cities on smooth, well-lit streets. This car is far bigger and more powerful, and this road is basically a boreen with ambition.

Underneath the wheels, he feels the surface start to gently rise. It’s cutting through dense, gloomy forest, steadily thickening with darkness on either side of the car. Donal knows this is because it’s gone six on an overcast, late-January evening, but it feels like it’s because the forest is absorbing the light, sucking it in, swallowing it up whole.

Feeding on it.

‘It’s so creepy out here,’ he says.

Steve, sitting in the passenger seat, snorts and says, ‘That’s, like, the whole idea?’ in a tone that adds a silent you idiot on to the sentence’s end.

A heat flares across Donal’s face.

He’s already downsized his goals from Do such an amazing job that you and Steve Dade cement a years-long professional partnership that will culminate in you both on stage at the Dolby Theatre holding a pair of little gold men to Don’t get fired before shooting starts. Donal has never held an assistant director position before. Not even close unless you counted the word assistant. His most recent job was glorified receptionist-slash-dogsbody at a casting agency. Getting a gig as Steve Dade’s AD on this was an incredibly lucky break and Donal cannot blow it.

The problem is that he’s intensely aware of that and has been a ball of acute anxiety ever since he reported to set. He can only hope that when shooting starts tomorrow, he’ll be better at his job than he’s been at making conversation.

‘This is such a waste of time,’ Steve says. ‘They’re probably not even there.’

‘We can leave a note.’

‘Can’t we just leave a note anyway?’

‘Joanne asked that we speak to them,’ Donal says, ‘as a courtesy. That you do.’

Joanne is the owner of Cedarwood House, their set, and also this other, smaller property, Cedarwood Lodge. Steve had refused to spend the money to book out the lodge as well, so here they are, driving to warn the Airbnb-ers who did book it this weekend about the shoot.

Steve groans like a teenager who’s just been ordered to go do his homework.

‘What are they even doing out here?’

‘Mini-break,’ Donal says. ‘A last-minute booking.’

‘Who books a house in a place like this in January? Wait.’ Steve twists in his seat to look back down the road. ‘Did you miss the turn? She said the gates were a mile apart. We should have— There!’

This exclamation coincides with him jutting an arm across Donal’s face to point at something on the driver’s side, obstructing Donal’s view and making him slam a foot on the brake in panic.

The car screeches and shudders to a violent stop that jerks both men forward against their seatbelts before shoving them back against them again.

‘Dude,’ Steve says. ‘What the fuck?’

Donal mumbles an apology even though it was clearly Steve’s fault, then looks for what Steve was pointing at.

The right headlight has found a wooden sign, hand-painted and peeling, nailed to a tree trunk at the edge of the road: Cedarwood Lodge, above a black arrow. In the gloom beyond, Donal can just about make out that the arrow is pointing to a pair of wrought-iron gates hung between two stone pillars. One stands open, inviting them to turn on to what looks like a dirt track through the trees that immediately disappears into a dense, inky blackness.

‘Cedarwood,’ Steve scoffs. ‘Where did they get the name? Aren’t these – what are Christmas trees?’

‘Firs,’ Donal answers. ‘And maybe they’re U2 fans.’ He turns to find Steve looking at him blankly. ‘That’s where Bono grew up. Cedarwood Road. In Glasnevin. They have a song about it. On Songs of Innocence.’

The blankness is morphing into bemusement, so Donal clears his throat and looks back at the gates, hoping the gloom in the car will hide his blushing cheeks. He just should stop talking to Steve entirely. Become mute. Stop the stupidity that is apparently intent on constantly leaking out of his mouth in the presence of this man.

‘Go on, then,’ Steve says, pointing. ‘Let’s go.’

Donal eyes the narrow entrance. ‘I should hop out and open the second gate, shouldn’t I?’

‘Don’t be daft. You’ve loads of room.’

‘Are you sure? I don’t think—’

‘It’s not a bloody bus you’re driving.’

It’s not a bus, no, but the gap made by the single open gate does not look as wide as the vehicle Donal actually is driving.

He bites his lip to stop himself from saying this out loud and lowers his window in the futile hope that this will somehow help him see in this dark. He swaps the brake for the accelerator and begins to turn the wheel, his grip slipping a little on a surface made moist by his own sweat. Tentatively he noses the car through the gap inch by inch, barely breathing, braced for the horror sound of a scrape.

Once he sees the rear of the vehicle has cleared the second, closed gate, he lets his muscles relax with warm relief and, accidentally, breathes a sigh of one too.

‘All right, Granny,’ Steve says.

It is indeed a dirt track beyond the gates, narrower than the road they’ve just left and dotted with unexpected mounds and water-filled potholes. The chassis bounces over and into every one, while Donal winces in time. Every cent on this shoot counts – because there’s so few of them – so of course they opted for the cheapest insurance cover on the car, the policy that probably says if you do any damage at all, you’ll have to pay for it out of your own pocket.

‘This is so pointless,’ Steve says. ‘They’re not even going to hear anything. Not all the way out here.’

And then, as if on cue, they hear something: a high-pitched, otherworldly, testicle-retracting shriek. Loud and getting louder, because whatever is making it is heading right for them.

A set of red glowing brake lights appear on the track up ahead. Except they’re not brake lights, because they can’t be, because they’re too high up off the ground.

Not lights, but eyes. Glowing red, in the middle of two enormous wings.

On something that’s flying.

At high speed.

Directly at them.

At the windshield.

The shrieking takes on a kind of raw, guttural sound that reminds Donal of the demons that get exorcised from dead-eyed, white-haired children in the kind of seventies horror movies he doesn’t have the stomach to watch. He jams on the brakes just as he hears Steve say, ‘What the—’ and then the shrieking reaches a fever-pitch that makes Donal’s eardrums thrum with pain, and then there’s yelling too, and then a whooshing sound, as the … the thing, this huge, black, feathered thing with a pair of glowing red eyes swoops past them and over the car and disappears into the night.

Silence.

Utter silence. As if, all around them, the dark is holding its breath.

Donal is holding his, has been holding his for way too long to be healthy, and now he starts gasping and coughing and trying to swallow down lungfuls of air, while also trying not to do this because he’s pretty sure he just made a fool of himself and nearly crashed the car and almost wet his pants because of an owl.

An owl.

Who, flying directly into their headlights, looked surprisingly large and like he – she? – had red eyes.

‘What,’ Steve says. ‘The fuck. Was that?’

‘An owl.’ Donal thinks he’s redeeming himself by saying this. Yes, he reacted like it was some kind of monster coming at them, but now he’s realised the error of his ways and can offer an informed explanation. ‘Barn owls make those kinds of weird screeching noises. That’s one of the explanations for banshees, actually. Owls and foxes. Foxes, especially, at this time of year. They’re mating calls, but they sound human. Well, human-like. That’s what people were actually hear—’

‘Foxes don’t fly,’ Steve snaps, ‘and that was way too big to be an owl. Did you not see the size of it?’

‘Yeah, but it’s just a perspective thing. It looked bigger because it was flying right at us.’

‘Or because it was bigger. That thing was as big as a man. The wingspan must have been, what? Five metres across?’

Donal would’ve gone with more like one, but he doesn’t say this.

‘Hey,’ Steve says then, ‘did you ever hear of the Mothman?’

A chill travels down Donal’s spine and into his bladder because, unfortunately, he has. The Mothman was a ghoulish, winged creature, larger than a man, with black feathers and burning red eyes, who was said to stalk the town of Point Pleasant, West Virginia. If you saw him it meant that some kind of awful tragedy was about to happen, or that you were watching a generally mediocre but occasionally terrifying early-noughties movie starring Richard Gere.

Donal had first seen The Mothman Prophecies as an impressionable eleven-year-old thanks to an irresponsible babysitter (his older brother) and for years had been convinced that its most disturbing sequence involved the Mothman walking on his wings, like a pterodactyl. But re-watching it (just once) as an adult, he’d discovered there was no such scene.

It must have come from one of the many nightmares he’d had in the weeks after his first viewing.

‘Because it looked just like that,’ Steve is saying. ‘The red eyes, the massive wingspan, the swooping down on to the road …’

‘It was just an owl.’

Donal is telling Steve this, but he’s also telling himself.

‘Like hell it was,’ Steve mutters. ‘But hey, did we pick the right place to make a horror movie or what?’

Final Draft is due to start shooting in twenty-four hours, on a secluded set, in the dead of winter. This first week will be all night shoots, in a week that Met Éireann promises will be plagued by violent storms and freezing temperatures. Donal hasn’t yet mastered talking to the director, let alone helping him achieve his vision and doing everything that an AD should do, which is basically holding the whole show together. If something goes wrong, the blame will almost certainly land squarely at his feet.

And mothmen, banshees …

They didn’t come to tell you that everything was going to work out just great, don’t worry, all good.

It was just an owl, Donal says silently, before releasing the brake and taking them onwards down the dirt track.

*

The track twists and turns through the trees, hiding the house until the very last moment. It’s a small, square, red-brick bungalow sitting in a puddle of gravel that crunches under the wheels as Donal pulls up, parallel to the muddy Ford Fiesta already parked there. Smoke billows from the chimney but only one of the windows – the nearest one to them, to the left of the front door – suggests there’s a light on inside. When the headlights disappear, the window transforms into a rectangle of buttery yellow glow.

‘Looks like a gatekeeper’s lodge,’ Donal says. ‘Only it’s a bit too far from the gate to do any keeping.’

Steve snorts. ‘Looks like a shithole to me.’

They get out, their breath clouding in the freezing air. The surrounding trees block what little is left of the daylight. The only way to know there is any is to look straight up, between the trees, into the patch of the blue-grey sky directly above their heads. In a few minutes’ time, it will be completely dark.

It’s deathly quiet. As they make their way to the lodge’s door, the only sound is the crunch of gravel underfoot, and then Steve’s firm double-knock seems to ricochet off the trees, dangerously loud.

‘They won’t be expecting anyone,’ Donal whispers. ‘Not out here. So let’s just hope no one has a gun.’

‘Or is a screenwriter.’

‘Or worse, thinks they’re one.’

Steve makes a humph noise that Donal chooses to interpret as a lazy laugh because, bloody hell, he needs the win.

They hear a rustling noise from inside and then the door, creaking open – just a few inches, enough to reveal a rusting safety-chain pulled taut and, beyond it, half the face of a man eyeing them coldly.

‘Hey there,’ Steve says, holding up a hand to signal that they come in peace. ‘Joanne asked us to call round – the owner?’

The only eyebrow they can see rises in question.

‘My name is Steve Dade.’ Steve pauses here to, Donal presumes, allow the man the opportunity to say something like, ‘Wow! Really? You’re Steve Dade?’ When it doesn’t happen, he pushes on. ‘I’m directing a movie that we’re shooting down at the main house—’

The door abruptly slams shut.

Steve is muttering a, ‘What the …?’ when the safety-chain rattles and the door re-opens, wide enough now to reveal the whole of the man.

‘Sorry,’ the man says. ‘Say again?’

The man is a little older than Steve, Donal would guess, so late thirties, early forties, but not trying as hard as Steve to look like he hasn’t had to start ticking the next box along on the form. He’s wearing jeans and an old T-shirt and his feet are in thick, woollen socks, the kind you wear inside hiking boots. Strong jaw, bright blue eyes. He’s holding a stemless wine glass, half-filled with red, and something smells good in the air that’s wafting out into the night from the space behind him.

They’ve interrupted his dinner, Donal thinks.

‘We’re shooting a feature,’ Steve says, ‘down at the main house.’ He points into the woods, pointlessly; the main house is at least a mile away through the trees, so there’s nothing to see. ‘A horror movie. Starting tomorrow evening. So if you hear any strange noises … We’ll mostly be shooting at night, you see, and there’s going to be a bit of screaming. You shouldn’t hear anything from here but just in case you do, we wanted to give you a heads-up. So you don’t, you know, think someone’s getting murdered and call the Gardaí.’ Steve laughs here. The man does not. ‘We’ve, ah, spoken to them too, so they should know to tell you anyway. The lads in the station in Durrus, I mean. But Joanne insisted we—’

‘We wanted to tell you ourselves,’ Donal interrupts, before Steve can suggest they’re only here because they were forced to come, or casually deploy any more phrases like shooting a feature, or refer to members of An Garda Síochána as the lads another time. ‘And to give you this, just in case.’ He hands over one of his business cards.

It’s a very simple affair: plain white, the thinnest paper-stock, Arial in black. All it says is Cross Cut Films above his name, email address and mobile phone number. Donal made them himself, on the inkjet in the production office, just this morning, because Steve said printing professional ones was an unnecessary cost.

‘This is Donal,’ Steve says. ‘My assistant.’

Assistant director, Donal corrects silently. His official credit, but not one Steve has thus far acknowledged in real life.

But then, everyone is wearing many hats on this project. Donal is also, effectively, the line producer and production manager. He’s his own assistant and an assistant to Steve – who is directing and producing – as well as acting as the assistant director. Assistant is probably just the easiest catch-all thing to call him, really, when you think about it. That’s all it is.

Donal hopes that’s all it is.

The man is frowning at the business card.

‘Don’t worry,’ Donal says quickly. ‘At this distance, with the trees, it’s very unlikely you’ll hear anything.’

The man opens his mouth to respond – to argue, Donal worries, and he’d be right to because if they’re not going to hear anything, why are he and Steve here to warn them not to call the Gardaí if they do? – but before he can, a new hand appears from behind the door.

This one has delicate fingers, pale skin, and tapered nails painted in a high-gloss red. It curls around the edge of the door and pulls it open wider, revealing a second occupant: a woman in a bathrobe. Her long, dark hair is dripping wet.

She takes the business card out of the man’s hands and asks Steve, ‘What did you say your name was?’

‘This is ridiculous,’ the man says to her, snatching it back. Then he turns and disappears into the gloom beyond the door.

A moment later, an internal door slams like a thunderclap.

The air swirls and shifts, infused with a new tension. Steve clears his throat and looks off to his left, into the black of the forest, which Donal instinctively knows, after just a few hours in this man’s presence, is a signal that his boss is done with this situation and now it’s up to him to extricate them from it.

‘Don’t mind him,’ the woman says, managing to pull her eyes off Steve long enough to roll them. ‘He’s been in a mood since we got here. Says he was told something about a sea view and of course he just cannot allow for the fact that maybe he looked at a few places and got two of them mixed up. He wants to move to somewhere else, but pickings are pretty slim around here. I guess it’s the time of year.’ She sighs. Eyes back to Steve. ‘Did you say you were the director?’

Donal thinks he recognises the tone, the accompanying expression on the woman’s face. This conversation is about to go one of three ways. One: she’ll ask Steve a bunch of stupid questions, starting with the classic, ‘I’ve always wondered … what does a director actually do?’ Two: she’ll pitch an idea she’s convinced would make a great film that in reality barely amounts to an anecdote. Three: she’ll say she’s always dreamed of being, or is, or thinks she could be, an actor.

Steve knows this too, because he says a curt, ‘Yep,’ and then, without leaving a pause, ‘Anyway, we should be getting back.’

‘Sorry to disturb your evening,’ Donal says. Steve is already turning to go, collecting Donal at his elbow, turning him around too just as Donal adds an excruciatingly cheerful, ‘Have a good night!’

They crunch their way across the gravel, back to the car. The woman stays standing in the open doorway, watching them, until Donal revs the engine and starts reversing. Only then does she turn and go back inside.

‘I think we should make as much noise as we possibly can,’ Steve mutters. ‘Make sure they leave.’

ACT I

Based on a terrifying true story.That hasn’t happened – yet.

Written byDaniel O’Leary

January 2022

Cross Cut FilmsTemple Bar, Dublin [email protected]

FADE IN:

EXT. TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN – DAY

Granite university buildings form an imposing U-shape around an expansive cobbled square in the heart of Dublin’s city centre. At the mouth of the ‘U’ sits the emblem of Trinity College Dublin: the 100ft campanile.

Hundreds of students mill about in early-morning sunshine, dressed for cold weather.

INT. CLASSROOM – DAY

A vast room with a vaulted ceiling, overlooking Front Square. Oil paintings of old white men hang from the walls in antique frames.

A dozen twenty-somethings sit around a table, listening intently to OLDER MAN 1 (50s, distinguished looking, designer knitwear) who is seated at the head of it. Beside him is OLDER MAN 2 (50s, distracted professor vibes, tweed blazer with scuffed leather elbow patches).

OLDER MAN 1

So if your characters don’t surprise you, how on earth do you expect them to surprise your readers?

Heads nod, sounds of agreement are made.

At the opposite end of the table sit KATE (20s, fresh-faced beauty, bookish) and GUS (20s, gangly, floppy-haired and badly dressed).

GUS

(whispering to Kate)

If your characters are genuinely surprising you, you should probably seek the services of a mental health professional.

KATE

(to Gus)

Ssshhh.

OLDER MAN 2

Unfortunately that’s all the time we have today. Round of applause, please, for our distinguished guest, who has been so generous with both his time and his expertise.

The students comply. Gus does a slow handclap.

OLDER MAN 2 (CONT’D)

And all the best with the Booker announcement. But of course, whatever happens, it truly is an honour just to be nominated, isn’t it?

Older Man 1 smiles tightly.

OLDER MAN 1

So they say.

The students collect themselves, stand to go. The room grows noisy with their leaving.

GUS

(To Kate)

It might be an honour but it’s not fifty grand, is it?

Kate slaps his arm in playful reprimand.

EXT. TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN – DAY

Kate and Gus make their way across Front Square, joining the flow of other students disappearing into the tunnel beneath the thick concrete and grimy windows of the Brutalist Arts Block.

EXT. BOOKSHOP – DAY

They emerge into chilly, midday sunlight and make a beeline for a bookshop housed in a distinctive, red-brick building with a pair of large bay windows at the front. The sign over the entrance reads ‘HODGES FIGGIS’.

One window displays multiple copies of the same book: Evenings by George Weston. Hanging behind them is a large photo of the author posing behind a chesterfield desk in a book-lined office, no computer in sight. George Weston is Older Man 1.

A small, handwritten note on paper torn from a pad and hastily taped to the glass at elbow-rather than eye-line says that Joel Jackson will be signing copies of his new book Inside in-store today.

Kate and Gus disappear inside …

INT. BOOKSHOP – DAY [CONTINUOUS]

… and enter an expansive bookstore, full of nooks and crannies. Customers browse in respectful quiet, as if in a library.

Kate goes to shelves marked ‘Fiction A-Z’ and starts reading the spines.

GUS

What are you looking for?

KATE

That book George mentioned. The one about the British butler during World War II.

GUS

(scoffing)

George? You two are BFFs now, are you?

KATE

That’s what he said to call him.

GUS

He didn’t mean it.

KATE

Help me look or be quiet.

GUS

I’ll be quiet in Crime.

He leaves Kate to her search, which ultimately proves fruitless. Kate spots a man stacking books on a table nearby and approaches him.

This is JOEL (30s, handsome, wearing trendy trainers and trendy frames).

KATE

Sorry to bother you, but do you have The Remains of the Day?

JOEL

Oh – I don’t work here. Sorry.

Kate looks down at the table, confused.

JOEL (CONT’D)

These are mine. I mean, I wrote them. It.

An acrylic sign is sitting on top of the books. He turns it around so Kate can see it. It’s a picture of Joel holding a copy of Inside.

KATE

Oh God. I’m so sorry.

JOEL

Don’t be. Happens all the time. And at least you asked me about a book. Usually people are looking for the toilets.

KATE

Sounds glamorous.

JOEL

Hey, it gets me out of the house.

KATE

Are you here to do a signing?

JOEL

I am, but alas no one is here to get their book signed.

KATE

That’s not true. I’m here.

JOEL

You’re looking for Ishiguro.

KATE

Not any more. I’ve changed my mind.

JOEL

You shouldn’t. Trust me.

KATE

Do they teach you how to promote your own books or are you just a natural at it?

(pointing to the books)

Will you sign one for me?

JOEL

Are you sure?

KATE

I have enough points on my loyalty card to cover it, so I don’t really need to be, do I?

JOEL

Well, God knows I need the sale.

He picks up a copy and takes a pen from a pocket.

JOEL (CONT’D)

Who should I make it out to?

KATE

Kate. Spelled the usual way.

Joel signs the book.

JOEL

Nice to meet you, Kate spelled the usual way. I’m Joel.

KATE

I should hope so. Otherwise you’re just desecrating that book.

Joel laughs.

JOEL

So what do you do, Kate? Besides take pity on unpopular authors.

He hands the signed book back to her.

KATE

I dream of being an unpopular author someone else takes pity on one day. I’m a student. On the Creative Writing MA, across the street.

JOEL

So you’re a writer.

KATE

Trying to be.

Gus reappears, clutching a couple of blood-spattered true-crime books.

KATE (CONT’D)

(to Joel)

This is my friend, Gus. He’s trying to be a writer, too.

(to Gus)

This is Joel. And this is his book.

Gus and Joel exchange silent nods. Gus looks down at the table of books, makes a face.

GUS

Looks like it’s flying off the shelves.

KATE

(warningly)

Gus.

GUS

(faking innocence)

What?

A beat of awkward silence.

KATE

(to Joel)

Well, we better go. We have a seminar starting soon.

JOEL

And I have a very busy afternoon of standing here alone to get to.

KATE

Can I ask you something?

JOEL

Sure.

KATE

What’s the best writing advice you ever got?

Gus rolls his eyes while Joel considers the question.

JOEL

I’d have to say … Write the book you want to read but can’t find on the shelf.

KATE

Oh, that’s good.

JOEL

Isn’t it? Unfortunately I didn’t take it, so now no one else wants to read it either.

KATE

That’s not true. I do.

JOEL

Get back to me in fifty pages.

KATE

I will.

JOEL

I hope so.

His gaze lingers on Kate until she looks away, blushing.

A cranky Gus pulls her away by the elbow. They join the queue for the cash registers.

While awaiting her turn, Kate opens her copy of Inside and sees that Joel hasn’t just signed it – he’s written his number in it too. She looks back towards the table where Joel is standing, meets his eye and smiles.

DISSOLVE TO:

ONE

It all started the day of the audition.

A TV commercial, for Neutraxium, a headache pill that sounded like something that would give you a headache. I was auditioning for the role of ROLLERBLADER (female, 20–22, Caucasian), a ‘natural beachy beauty, subtly sexy, with a gym-toned body and California-cool, Gwyneth vibes’, who simply refused to let headache pain get in her way.

I was none of those things, but I guess that’s why they call it acting.

The hallway outside the audition room was lined with the usual suspects: young, fair-haired, willowy white women who had grown up in towns where their beauty was considered exceptional – who had then moved to LA to discover the same face just helped them fade into the crowd.

I took an empty seat and surveyed the competition while pretending to read over my lines – line. About half of the other auditionees were actually in rollerblades or sitting with a pair of them lined up on the floor by their feet. No one was wearing clothes that extended beyond the shoulder or below the knee, even though it was a January day and, for LA, a cold one. Most were lightly tanned and sporting beachy waves. Nearly everyone was sipping continuously from a water bottle bigger than their head. A reusable one, of course.

My beach waves were frizz; my skin was the pasty, bluish pallor of someone who spent most of the daylight hours inside under fluorescents; and my single-use plastic cup was filled with a sickly sweet, artificially flavoured iced-coffee concoction. But casting directors weren’t looking for perfect. They didn’t know what they were looking for, especially when it came to commercials. Every time I auditioned for one, I saved the description to a note in my phone just so I could compare it to the actor in the finished product. To date, I’d failed to find a good match.

And I had a lot of those notes.

‘They’re running behind,’ the woman sitting opposite me said – to me, I realised after a beat. She was one of the rollerbladed, absently slicing alternate feet beneath her chair, making a repetitive scraping noise that was already annoying. ‘Ninety minutes, the assistant said a half-hour ago.’

I nodded and smiled because I had never been to a single audition where things weren’t running behind and because I wanted to discourage a longer conversation.

That was when the first call came in.

I felt my phone ringing before I heard it, buzzing against my thigh through the fake leather of my fast-fashion handbag. The other eyes in the corridor turned towards me; several signs were stuck along its length, warning NO PHONES.

I rooted for mine, wondering who was calling me. The pool of potentials was embarrassingly small. I hadn’t been at all good at making friends in LA, but I’d excelled at losing touch with the ones I had back home. My guess was that it was someone from work, wondering if I’d swap a shift. They all knew I was good for it because I was never going anywhere and never doing anything.

But the number on screen started with the country code for Ireland, and the numbers that followed it told me the call was coming from a mobile. The fact that I was looking at numbers at all and not a name told me that the mobile belonged to someone who wasn’t in my contacts, someone I didn’t know.

Or didn’t want to know.

I kept my breath steady, told myself not to overreact. Auditions were bad enough for me these days without adding extra, unrelated anxiety to the mix right before I got in the room. I stared at the phone until it cut off mid-ring.

Either the caller had hung up or they were leaving a voicemail. I hoped for a voicemail, ideally one that would leave no doubt that the person thought they were calling someone else, that this was just an innocent wrong number. I counted off the seconds, imagining the length of a standard message, but the phone’s screen dimmed, then went black.

No new voicemail notification.

I copied the number and pasted it into Google on the off-chance it appeared on someone’s professional website or a forum warning about scams, but there was no match for it on the internet.

In my hand, the phone had grown slick with sweat.

‘Everything all right?’ Rollerblade Girl asked me, and I immediately rearranged my face into a smile and looked up at her and said yes.

But even then, it already wasn’t.

Nearly two hours passed before I got in the room.

It almost always looks the same. A hotel meeting space with no windows, basement level, cheap to rent. A trestle table at one end with a quartet of bored-looking people sitting behind it, side by side and facing you. One has a clipboard and at least one other one is looking down at their phone, ignoring you. No one is ever introduced and their roles are never made clear, but you can safely assume that the one who talks to you is the casting director. Off to one side will be a person operating a camera who won’t acknowledge your presence in any way except to point it at you, and there’s a bit of red tape on the floor showing you where to stand.

Once upon a time, in another life, this had been my domain. I’d enter these sad little rented rooms and meet their stone-faced occupants feeling like an undefeated boxer entering the arena who knows her opponent would do well to avoid a KO in the first round. Outwardly I was charming and always just on the right side of the confident versus cocky line. I’d often walked out of these rooms knowing that in a few hours’ time, I’d get a call to say I’d been offered the job.

I used to be great at auditions, but now I just hoped to get through them.

I took my spot on the tape and flashed a smile at each of the blank faces in turn. Only the red-haired woman on the end returned it.

Casting director: identified.

‘We’ll just get you to do a quick ID to camera,’ she said.

My palms were clammy; I tried to wipe them discreetly off my jeans. Then I turned to face the lens and said, ‘I’m Adele Rafferty, auditioning for the role of Rollerblader, and I’m self-represented,’ as confidently as I could, which wasn’t very confidently at all seeing as the very first thing I was telling them was that I was agentless, that I couldn’t get an agent.

If there was any flash of recognition at my name, I missed it.

That ship had sailed.

And then sunk.

And anyway, I didn’t want to be recognised these days. That was the whole reason I’d come out here, to LA.

‘Are you American?’ Red Hair had an iPad in front of her on which I thought I could just about make out my headshot in matchbox size, upside down: my CV. She was zooming in on the text with two fingers.

‘Irish,’ I said. ‘I moved here six months ago.’ It was important to say the second bit because otherwise they thought you were saying you were Irish-American, because American people with Irish relatives inexplicably said they were Irish too, and you, the actual Irish person, were forced into doing your own differentiating.

Red Hair frowned, so I jumped straight in with the answer to the question I knew was forming on her tongue.

‘I have dual citizenship,’ I said quickly, ‘because of my mother.’

Translation: I can work here legally, it’s okay.

‘And you’re’ – Red Hair’s eyes flicked to the iPad – ‘twenty-two?’

I nodded. ‘Yes.’

And indeed I had been, four years ago.

‘Can you rollerblade?’

‘Yes.’

I couldn’t not rollerblade. I’d never tried. I was the Schrödinger’s Cat of rollerbladers: until I put a pair on, I both could and couldn’t do it. Both were equally true until the attempt. If I managed to not only get through an audition but also do well enough to be offered the job, I could certainly figure out how to rollerblade before the shoot started.

One obstacle at a time.

‘Have you appeared in any pharmaceutical campaigns in the past?’ the casting director asked, her eyes still on the iPad.

‘No,’ I said.

‘Have you appeared in any campaign in the last year?’

‘No.’

‘Whenever you’re ready then,’ Red Hair said, finally looking up at me. A little smile. ‘In your own time.’

I smiled back. I tried to push the phone call from home out of my mind. I tried to trick myself into thinking I was myself from a year ago, when everything was different. When I was different. The Before me. I hoped I was only imagining a sheen of sweat at my temples, my hairline, across my upper lip.

I took a deep breath.

Then I stared down the barrel of the lens and said, with the theatrical defiance of a woman climbing up something in tiny white shorts who Tampax would have you believe has her period, ‘I refuse to let headache pain get in my way!’

Count to two, turn back to Red Hair. She was nodding thoughtfully, like she was tasting a food she’d never tried before and the jury was still out on whether she liked it or not.

The other three continued to look like they were waiting for the valet guy to reappear with their car outside a restaurant that had just served them an expensive lunch they hadn’t enjoyed.

‘Great,’ Red Hair said in a tone that suggested this was, at the very least, a gross exaggeration. ‘Now I just want to try a couple of things, okay?’

I nodded vigorously to show I was willing. This movement pushed a trickle of sweat out of my hairline and down the side of my face.

‘Great.’ The word was losing all meaning. ‘Let’s take it again, but with a different emphasis. Let’s say … On “refuse”.’

‘Sure.’ I counted to five. I took a breath. I stared down the lens which I knew was picking up every single bead of moisture on my face, which only made more rush to join them. ‘I refuse to let headache pain get in my way!’

‘Hmm.’ Red Hair did some more imaginary food-chewing. ‘Let me hear it with the double emphasis.’

‘I refuse to let headache pain get in my way!’

‘Bring it down a little …’

‘I refuse to let headache pain get in my way.’

‘Slow it down …’

‘I refuse’ – pause – ‘to let headache pain’ – pause – ‘get in my way.’

I was sure now that my face was not only shiny with sweat but blood-red beneath it, too.

‘Not that slow,’ Red Hair said, frowning.

‘I refuse to let headache pain’ – pause – ‘get in my way.’

‘Can we just do one where you refer to it as a “little headache pain”? Like you’re minimising it. It doesn’t affect you. It’s trivial.’

‘I refuse to let a little headache pain’ – pause – ‘get in my way.’

The heat on my cheeks felt like it had developed its own pulse.

‘Now bring it back up for me …’

‘I refuse to let a little headache pain’ – pause – ‘get in my way!’

My right eye started to sting; sweat had dripped into it. Red Hair was wearing a wool cardigan over a white button-down shirt with a silk scarf draped around her neck, which meant it wasn’t warm in this room at all, which meant my being warm would be even more noticeable and definitely not mistaken for anything other than nerves.

As I thought this, the man sitting at the far end of the table finally looked up, looked at me and wrinkled his nose in disgust.

I knew then I wasn’t getting this job. I wasn’t even getting called for any job involving this casting agency ever again. Right now, I was less natural beachy beauty with California-cool, Gwyneth vibes and more Have you or someone you love suffered adverse side-effects of Neutraxium?

If this commercial ended up going in a different direction, as they so often did, and that direction was ambulance-chasing law firm canvassing for more plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit against the headache pill’s manufacturers, then maybe I had a chance.

A small one.

But otherwise …

‘Great,’ Red Hair said. ‘Let’s just try one more thing. This woman is beautiful and confident and strong, but she’s also not too any of those things, an everywoman. She’s aspirational, but also relatable. You want to be her, but you’re also already her. Do you know what I mean?’

I knew better than to say that nobody could know what that meant, that I didn’t even believe Red Hair did.

‘Think about that,’ she said. ‘Then take it again.’

I did what she asked. Or tried to.

‘Thanks,’ she said then. ‘Ah – she glanced back down at her iPad – ‘Adele.’

I mumbled something that hopefully sounded like, ‘Thank you for the opportunity,’ and then an assistant was suddenly there, to my right, as if she had materialised silently from the wall.

I knew I was supposed to follow her out of the room, so I did.

‘They’ll be in touch,’ the assistant said to me once we were in the hallway, which was what every assistant had said to me at this point in every other audition. But then she added something unexpected. ‘I loved Winter Snow, by the way. Is it true they’re making a sequel?’

This comment set off a torrent of contradictory feelings. Elation because she’d loved the movie. Insult because she was asking about a sequel when my character had died at the midpoint. Shame because this conversation was happening at an audition for a one-line part in a headache-pill commercial I definitely wasn’t getting. Fear that she’d recognised me, and that she’d heard what had happened the last day I’d been on a set, that the whispers had not only managed to cross the Atlantic after me but the continent of America too.

The day I’d dreaded for months had finally arrived. My plan had failed. I couldn’t escape.

My face must have fallen as I cycled through these emotions because the assistant frowned and said, ‘Sorry. I saw it on your CV.’

‘Oh— No.’ I waved a hand. ‘It’s totally fine. Thank you for saying so. I appreciate it.’

What I really appreciated was that she hadn’t recognised me, actually. She’d just seen Winter Snow on my CV. It was also cooler out here, in the corridor and, away from the Trestle Table Quartet, the anxiety that had been seeping out of my skin during the audition was just an unsettled feeling in the pit of my stomach.

The invisible vice around my chest sprang open, allowing me to breathe again.

‘It was such a fantastic role,’ I said, smiling. Maybe I could salvage this now, here, with the assistant? There was no way I was getting the commercial, but if I could just avoid getting struck off the agency’s list … ‘Incredible writing.’ No harm to redirect the glow of achievement on to the rest of the team. The great thing about me is how humble I am. ‘And I don’t know about the sequel, but I hope so.’

It was by far the best acting I’d done all day.

Out on the street, I held my arms away from my sides in a futile attempt to dry my armpits and hoped the Uber I couldn’t afford but had to summon because I didn’t drive – in LA, yes I know – would have ice-cold A/C on full blast.

That’s when I saw I’d had a second call.

The same Irish mobile number had called my phone ten minutes before, when I’d been in the audition room, looking like I desperately needed to take a couple of Neutraxium.

But I still had no new voicemails. I hadn’t replaced the Robot Lady greeting with one of my own and I wondered if that was why the caller wasn’t leaving a message: they weren’t sure if this number was actually me. If that was the case, I wouldn’t do anything to confirm it for them.

I was still holding the phone when it rang again.

I know now what, let’s be honest, I knew then: I shouldn’t have answered it. But a little bit of misplaced hope can be a terrible thing. Because what if it was someone back home calling to give me the second chance I desperately needed? To offer me the role that would make everything better, that would carpet over the last horrendous year, that would make everything right and okay and good again, that would make me feel that way?

I pressed ACCEPT and put the phone to my ear.

I wasn’t entirely reckless. There was only a minute chance this phone call was a good thing, and an overwhelming likelihood that whoever was on the other end of the line was bad news. So I would say nothing. Let them identify themselves before I confirmed this number belonged to me.

But there was only silence on the line.

They didn’t say anything either.

They were waiting, too.

And the silence wasn’t total. There was breathing. I put a finger in my other ear and turned away from the traffic to hear it better. Yes, there it was: steady, regular breaths. Louder than normal, if I could hear them down the phone while standing on a kerb on Sunset in the middle of the day. Masculine, maybe. Sort of …

Patient.

There were five thousand miles between me and whoever was at the other end of the line, but in that moment, the sounds of exhalation in my ear might as well have been a breath on my neck.

And then—

Click.

Whoever they were, they’d ended the call.

TWO

I got the Uber to bring me straight to work.

I worked reception at the Goodnite Suites at Universal, a two-storey motel painted in Heartburn-Remedy Pink that had been used as the backdrop for at least half a dozen true-crime re-enactments. Our guests were mostly families making a pit stop at Universal Studios on their Californian adventure. I worked second shift so I met them minutes after they’d arrived, at check-in, when they were still excited and happy and hadn’t yet realised that even though we had ‘Universal’ in our name, we were actually five miles away from it, in Burbank; the schedule of our complimentary shuttle bus was more aspirational than anything; and our rooms were very popular with the local cockroach community. All I had to do was smile, make sure they heard the accent and present them with a voucher for our dingy poolside bar in a way that made it seem special when actually we handed one out to every single guest.

Every hour I worked at the Goodnite dragged, but that afternoon it felt like the clocks were ticking backwards. I could only push the anonymous calls out of my mind long enough to wonder if I’d been too hard on myself, if things hadn’t gone as badly as I’d feared and there was still a possibility, however minuscule, that I might get a call-back.

I’d be different at the call-back. I’d have my nerves under control. I’d bring some Winter Snow anecdotes to casually share with the assistant. I’d be the old me, the real Adele Rafferty.

The one who didn’t think twice about answering her phone.

And then I heard a voice on the other side of the reception desk say, ‘Oh, my God. It’s Wendy!’ and time came to a sudden, complete stop.

Female. Irish accent. Over-excited.

My stomach was sinking before I even raised my eyes.

Standing in front of me was a family of three: mother, father, lanky blonde girl of about nine or ten. The girl had a smartphone that had all her attention and the father was looking around, appraising the place with an expression that suggested he was finding it wanting. The woman was staring at me, smiling manically, eyes wide with excitement.

‘Wendy!’ she said again.

I was not Wendy, but I also was Wendy, and this was the nightmare scenario I’d been dreading ever since I moved to LA.

Or at least ever since, having moved to LA, I realised I was going to have to get a normal job here.

‘I have to tell you,’ the woman said, ‘I am such a big fan!’

She didn’t have to tell me that it wasn’t of me, but of These Are the Days, Ireland’s second-worst soap opera and my employer for some fourteen years.

‘Great,’ I said in the Red-haired Casting Director sense of the word.

I hadn’t planned on becoming an actor and I’d certainly never planned on being the child version. But These Are the Days had had an open casting-call at a hotel in Cork that my best friend, Julia, had convinced her mother to bring her to. On the same day, my mother had needed a babysitter and had asked Julia’s if I could tag along. The casting director spotted me on the sidelines and got me to parrot off some lines, and within weeks I had a part-time job playing Wendy Morgan, youngest daughter of the drama-attracting Morgan clan – and loving every single minute of it.

I was an actor before I ever wanted to be one, but once I was, I never wanted to be anything else even half as much. At sixteen, I quit school and went full time. At twenty-three, over the show’s summer break, I played a supporting role in my first ever feature film and non-soapy-suds acting gig, Winter Snow. When it was released the following year, everyone who mattered said it was good and, more importantly, that I was good in it.

My phone started ringing. My agent realised I existed. Glossy magazines that came free inside the weekend papers started draping me across couches dressed in sequinned dresses I couldn’t afford and printed interviews with me under headlines like PROMISING YOUNG WOMAN and OUR NEXT BIG THING and DON’T CALL ME THE NEXT SAOIRSE RONAN because I wasn’t used to doing press and routinely made silly, off-the-cuff remarks to journalists that they gleefully seized upon and printed out of context. I even got an IFTA nod: (one of the) Best Supporting Actress (nominees) 2020, thank you very much.

All the while, my resentment towards These Are the Days grew – because whenever the phone rang, I had to say no to whatever was being offered to me by the person on the other end. We filmed six days a week for ten months of the year and with my stock rising, the powers-that-be weren’t inclined to enrol Wendy in a faraway college she’d only come home from the odd weekend, or put her in a six-month coma following a pile-up on the motorway that – twist! – she’d wake up to remember she’d caused. (All ideas: actor’s own.) So I quit the show.

The bosses at These Are the Days, not at all impressed with my abrupt and ungrateful departure, made sure it would be a permanent one and killed me off in a DART derailment that unfolded in primetime over five nights. It sent ratings through the roof, so I ended up leaving an even more popular show than the one I’d decided to leave. What I didn’t understand was that I was getting offered all those other things because I was on a popular show. The directors who took me out to boozy lunches so they could talk to me about their ‘vision’ weren’t doing it because they thought I was an exceptionally good actress, or even an okay one. They were doing it because they hoped I’d get the These Are the Days viewers off their couches and into the cinema, or at the very least forking out for a movie-on-demand.

When Wendy Morgan died, all my glittering opportunity went into the prop-grave with her. I hadn’t booked a single paid acting-gig since, at home or here in LA where, like so many deluded Irish actors before me, I’d moved to pursue new opportunities six months after I’d left the show, six months ago.

Well, that wasn’t strictly true. I had booked one paid acting-gig, back in Ireland. But I’d never actually got paid for it, because it was on that set that everything had gone so inexplicably, horribly wrong. My cheeks still burned at even the most fleeting thought of it and I mentally pushed the memory away now.

There were just as many opportunities in London. In New York, even, if I’d had more fight in me, if it wasn’t taking everything I had back then just to put one foot in front of the other. But I picked the place that was furthest away, the city to which there were no direct flights from Dublin, in a time-zone whose morning was Ireland’s night. Where I could walk into an audition room safe in the knowledge that none of the Trestle Table Quartet knew about what had happened.

It was just a bonus that that was also the city where almost everyone lived in the space between their dreams and reality, where it was okay to desperately want to be the thing you weren’t yet, but the very fact you lived there still sounded like some kind of success to people back home.

Adele Rafferty? She’s in LA these days. Yeah, things must be going well.

I smiled weakly at the woman on the other side of the reception desk because I didn’t know what else to do.

No one back home knew I was working at the motel. I hadn’t even told Julia, for God’s sake; I couldn’t bring myself to. Through a series of vague assertions and white lies, I was letting everyone think that I was getting enough acting work to keep me going. Was this woman about to ruin it all? Was her next move to ask for a selfie? Would my shame go viral?

The idea of there being a new picture of me online set off a wave of mild nausea. When I left the show, I deleted all my social media accounts. I started to feel, looking at them, the eyes of everyone else who was looking at them, the silent sea of strangers who – I was convinced – sat in judgement of me, who were waiting with bated breath to see me fall.

And I had fallen, so every time my phone dinged with a notification, I was terrified it was someone who’d found out about that, helping everyone else find out about it via a Twitter thread or an Instastory.

It was just a bonus that my lack of an online presence was now keeping evidence of my abject failure to achieve my life’s primary goal off the phone of the people I knew, the faces I recognised. Family, friends, peers.

I didn’t want that situation to change.

On the other side of the desk, the woman’s smile had dimmed.

‘What are you doing here?’ she asked.

‘Researching a role,’ I said, the implication of my conspiratorial whisper being that no one else was supposed to know. And then, even though it was difficult, what with the full, crushing weight of my deep shame pressing against my chest, I said, at a normal volume, ‘Welcome to Goodnite Suites. What name will help me find your reservation today?’

I pocketed my phone, mumbled something about cramps to my colleague and escaped back-of-house.

There was a housekeeping cart sitting outside the staff toilet with various partially consumed foodstuffs on top: a six-pack of Coke with three missing, an already-opened tube of Pringles, a half-full bag of miniature Snicker bars. Left behind by guests, collected by the housekeeper.

I grabbed a fistful of Snickers on the way in, went to the further of the two stalls, sat on the toilet lid and stuffed two of them, whole, into my mouth.

In the last few months I had really begun to understand why people overeat. It isn’t what they eat, it’s why they eat it: because when you feel literally full from food, it’s a brief respite from feeling figuratively empty inside.

As I swallowed, I decided I was done: I was quitting acting.

No, that wasn’t what I needed to do. There was no acting to quit. What I needed was to stop wanting it to happen.

And I was going to.

Right now.

To continue with this idiocy was to delude myself into ignoring the realities of the situation. I couldn’t get work at home; what had happened had put paid to that. But I could only get work at home, where I was a tiny fish in a puddle of pond water. Out here, in LA, I was a flake of fish skin in the Pacific.

And if by some miracle I did get work here, and that work led to more work, and that work led to even more, proper, high-profile work … Well, eventually my past would catch up with me, like the spread of red dots on a map of the world in a Hollywood disaster movie, growing large enough to touch each other and merge into one.

I’d have to walk into a room or into a table-read or on to a set where I’d know what the eyes on me were thinking, what they were thinking of.

I wasn’t ready for that yet.

I didn’t know if I’d ever be.

Why the hell was I doing this to myself? Everything would be so much easier if I stopped trying to be an actor. Everything would be better.

So I was going to stop trying, starting now.

Then I took out my phone and saw I had a new email from the Neutraxium commercial casting agency, and a gold firework of hope exploded in my heart.

I’d never once got an email telling me I’d been unsuccessful at an audition. You were expected to deduce that from the fact that you hadn’t got one after an unspecified number of exquisitely torturous days.

So if they were emailing me …

Oh, my God.

Had I just had The Moment, the one where the despairing actor convinces herself her dreams must die right before she gets the call that makes them happen?

I saw a flash of future-me sitting on a leather couch on The Late Late Show’s set, dressed in something expensive a stylist had borrowed, telling Ryan the huh-larious story of how I’d been sitting on a toilet, crying and stress-eating miniature Snickers, when I got the news that I hadn’t booked the cheesy commercial that morning because the casting director had been so taken with me that she’d sent the video of my audition to David Fincher/Emerald Fennell/Jordan Peele (delete as appropriate) who’d cast me in the role for which I’d just collected an Oscar a few days before, and everyone would be far too busy being impressed with me to even remember that other business from some no-name movie set forever ago that they’d only heard vague, unsubstantiated rumours about. All I can say about that, Ryan, is that it wouldn’t have happened to a man.

I opened the email.

Thank you for attending the audition this morning. Just to let you know our Neutraxium commercial has been cast. We look forward to seeing you for something else in the near future.

The words ‘Neutraxium commercial’ were in a different font, bigger and in colour; it had been inexpertly copied and pasted in.

I deleted it.

I leaned my head against the side of the stall, closed my eyes and envied all the people who didn’t want things.

I was really done now. Really. Fully resolved to wake up a different Adele tomorrow. One who didn’t want anything except not to want anything at all. I would just live my life. I would take some time to make new goals – small, normal, ordinary ones; achievable ones. Dreams would mean the things I saw while I slept. I would move somewhere where coffee shops were full of baristas and coffee-drinkers, not auditioning actors and wannabe screenwriters tinkering with their specs. Where people were happy with their lot, because they had the good sense to recognise that their lots were a lot. I would stop tying every knot of my self-worth to what I did for a living and start actually living instead.

I popped another Snickers.

This was a new feeling. I had never seriously considered giving up before. I imagined a different me who didn’t care that she’d never had the acting career she’d dreamed of, and it made me feel a little light-headed, sorta floaty, like I was being untethered from the only driving force I’d ever known.

But I meant it, I really did. We’ll never know now, but I think if I’d just had a chance to sleep through the night that night, everything would’ve been different. The problem is that successful actors’ careers are hardly ever a steady graph of failing upwards. Read their biographies, watch their interviews. It’s not that they put in the hard graft, time and dedication and then one day, after ten thousand hours or however much that shite supposedly is, they reached the next level and got The Call.

The Call can come at any time.