Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

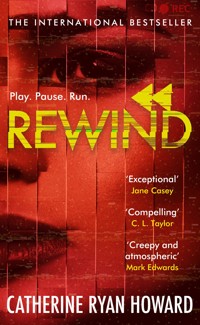

· · AN IRISH TIMES BESTSELLER · · · · Shortlisted for the 2019 Irish Independent Crime Fiction Book of the Year· · ___________________ From the bestselling, multiple prize-shortlisted novelist Catherine Ryan Howard comes an explosive story about a twisted voyeur and a terrible crime... PLAY Natalie knows there's something creepy about Andrew, the manager of her isolated holiday cottage. She wants to leave, but she can't - not until she finds what she's looking for... PAUSE Andrew is watching his only guest via a hidden camera in her room when the unthinkable happens. A shadowy figure appears on-screen, kills the woman and destroys the camera. REWIND This is an explosive story about a murder caught on film. You've already missed the start. To get the full picture you must rewind the tape and play it through to the end, no matter how shocking... 'Catherine Ryan Howard is a gift to crime writing. Her characters are credible, her stories are original and her plotting is ingenious. Every book is a treat to look forward to.' Liz Nugent ___________________ Don't miss Catherine Ryan Howard's The Nothing Man. Published August 2020...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 482

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Wonderful... It confirms [Ryan Howard’s] position as a major new talent in thriller writing.’ Daily Mail

‘Catherine Ryan Howard is a gift to crime writing... Every book is a treat to look forward to.’ Liz Nugent

‘Rewind is brilliant: an expertly constructed thriller that plays on our worst fears about modern life... Exceptional, original and compelling writing that’s a joy to read.’ Jane Casey

‘Chilling and mystifying from the get-go... Fresh and modern contribution to Ireland noir.’ Times Crime Club

‘Compelling, unsettling and creepy; Rewind is an ice-cold finger of a book that will send a shiver down your spine.’ C.L. Taylor

‘I was riveted... So very clever... and just gripping the whole way through. Ryan Howard is a superstar.’ Jo Spain

‘Reminded me of Ruth Rendell: Catherine Ryan Howard is a genius at psychological suspense.’ Elizabeth Haynes

‘A hugely compelling thriller. Twisty, suspenseful and totally engrossing. SUPERB.’ Will Dean

‘Creepy, atmospheric and beautifully written, this is her best one yet.’ Mark Edwards

‘Completely immersive, deliciously creepy with the darkest of twists... This is a book that grabs your full attention and does not let go.’ Dervla McTiernan

‘One of the best Irish crime writers around... Authentic and true... Supreme entertainment.’ Sinéad Crowley

‘Oh, my word! I couldn’t turn the pages fast enough... Excellent story-telling. A compelling read.’ Patricia Gibney

‘Compelling and brilliant. The perfect read for any crime fiction fan.’ Olivia Kiernan

‘I COULD NOT PUT IT DOWN. The very definition of a compulsive read.’ Fiona Cummins

‘Terrific... Kept me hooked from the first page to the last.’ Gilly Macmillan

‘Twisty and twisted... Loved it!’ Caz Frear

‘A top-class thriller.’ Irish Times

‘Superbly chilling.’ Hazel Gaynor

‘A chilling, powerful, thrilling tale.’ LoveReading

‘A story that will absolutely hook you from page one. Fantastic.’ Amy Lloyd

‘Claustrophobic, terrifying and most of all satisfying... Totally gripping.’ Claire Allan

‘A deftly written page-turner that keeps you guessing.’ Zoje Stage

Catherine Ryan Howard was born in Cork, Ireland, in 1982. Her debut novel Distress Signals was published by Corvus in 2016 while Catherine was studying English literature at Trinity College Dublin. It went on to be shortlisted for both the IBA Books Are My Bag Crime Novel of the Year and the CWA John Creasey/New Blood Dagger. Her second novel, The Liar’s Girl, was published to critical acclaim in 2018 and was shortlisted for a Mystery Writers of America 2019 Edgar Award for Best Novel. Rewind was shortlisted for the IBA Irish Independent Crime Fiction Book of the Year. She is currently based in Dublin.

Also by Catherine Ryan Howard

Distress Signals

The Liar’s Girl

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2020.

Copyright © Catherine Ryan Howard, 2019

The moral right of Catherine Ryan Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 658 4E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 657 7

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To Mum, for introducing me to books

In a room of shadows, a woman sleeps.

She is the bulge on the right side of the double bed. Strands of dark hair splayed across a pillow. One bare arm outside the sheets, a wedding band visible on her ring finger.

Unaware that she isn’t alone.

This room is an unfamiliar one for her, even more so in the dark. Were she to wake up right now she might lift her head, prop herself up on her elbows and turn her head to look around it. Gradually her eyes would adjust and shapes would emerge from the dark.

After a moment, she would remember where she was and why she had gone there.

How long would it take her to see the shape that doesn’t belong?

It stands stock still in the corner, arms down by its sides. The clothes are dark and bulky – layers, perhaps against the winter cold. Gloves on the hands, a balaclava on the head. The balaclava is twisted slightly to one side so the eyes are barely visible and the slit for the mouth shows only some cheek.

Watching.

Watching and waiting.

Waiting to use the knife with the long, serrated blade pressed against its side.

Time passes.

The sleeping woman stirs – her legs move; she turns over; the arm slips beneath the covers – but she does not wake. The dark figure moves closer to the bed until it is standing beside it, looming over her. She does not wake. The gloved hand that isn’t holding the knife reaches out and gently strokes the woman’s face and still, she does not wake.

The intruder makes a circle with a thumb and middle finger and flicks the woman’s cheek, hard, because – it’s clear now – it wants her to be awake.

A moment’s delay.

Then a frenzy of motion.

The woman’s eyes open. Her body rises, head and shoulders lifting from the pillows, legs rising beneath the sheets. She opens her mouth as if to scream but the figure clamps a hand over it, pushing her back down. The hand that’s holding the knife lifts to pull back the sheets with a finger. The woman is wearing a pair of shorts and a camisole top, her pale limbs are bare, exposed now. She sees the blade and her efforts to get away instantly intensify. Now her arms are flailing wildly, her legs kicking, her whole body jerking and contorting and squirming in the bed, fingers clawing at the balaclava—

The knife rises slowly in the air and then comes back down quickly, with force, plunging through the thin material of the woman’s top and disappearing into the concave flesh of her stomach.

Lifts again. Down again.

Into the chest.

Lifts again. Down again.

A slash across the woman’s forearm.

Lifts again. Down again.

Deep into the right side of her neck, just under the jawline.

The intruder steps back.

The woman’s hands go to her neck and almost immediately her fingers are stained by the blood that flows from the wound there. Her mouth is open as if in a silent scream.

Dark, spreading stains.

She turns, rolling on to her right side. Her uninjured arm reaches out, past the edge of the bed, towards the intruder, as if asking for help.

The figure in black bends to lay the knife on the bedside table before going to the chest of drawers pushed against the wall opposite the foot of the bed and destroying the camera hidden there.

It took Natalie most of the day to get away from Dublin City. From all cities. Cork was the last one she’d seen. She’d taken the train there first thing this morning, then transferred to this bus. It had snaked through Midleton – goodbye towns, too – and onwards, ambling along narrow, winding roads, the kind where the single white line painted down the middle was already more gone than still there. By the time she caught her first glimpse of the sea, she was 300 kilometres from her own front door. The traffic had thinned to the occasional passing car but the road twisted so much that the driver felt the need to blast the horn before each and every bend.

Natalie watched the bars signalling reception in the corner of her phone’s screen disappear one by one. She’d already lost her mobile data; it had dropped out somewhere between Castlemartyr and Ladysbridge. The device in her hand was now rendered almost useless. She pushed through the urge to connect to the bus company’s wifi for the last few minutes of the journey and let the phone slip into the depths of her handbag instead.

For all of a minute it felt like peace, a welcome release.

Then her fingers started to twitch and her palms grew clammy.

Natalie turned to concentrate intently on the view out the window. There was a stretch of smooth, grey sea wedged between the horizon and the darkening sky, marred only by two blots, one large, one small. Islands. She could just about make out the lighthouse sitting atop the larger one, looking like the nib of a fine pen from this distance. Then the bus took a hard right and there were only fields and trees and neat, old-fashioned bungalows, all surrounded by low pebble-dashed walls and set close to the road.

Then a sign for THE KILN DESIGN STORE & CAFÉ 500m.

Another one right behind it: WELCOME TO SHANAMORE.

She was here.

For the entire journey, a burning heat had been rushing against the back of Natalie’s legs from a grille beneath her seat. She was desperate for some cold, fresh air but also to stay on the bus, to let it take her back out of here again, to go home and talk to Mike and to forget about this while there was still time to.

But when the bus lurched to a stop, she got up and got off it.

She wasn’t prepared for the icy blast of late November air that pricked at her skin and instantly infiltrated her clothes. Gasping at the shock of it after the thick heat of the bus, Natalie hurried to pull on the coat she’d carried outside draped over an arm.

The train journey from Dublin to Cork had been just under three hours and she’d spent it obsessing over images of Shanamore she’d found online. This was having a disconcerting effect now that she was here. It was as if she was touring the set of a movie she’d watched a hundred times: everything was strangely familiar and yet totally foreign at the same time.

The bus had stopped outside the entrance to the car park of The Kiln, a trendy design store shaped like a barn that presumably flogged its locally produced crafts to well-heeled foreigners and its flat whites to local farmers. Its car park was the only smooth stretch of tarmacadam surface in Natalie’s line of sight. There was the church, rising up behind her, the tallest thing for miles. There was the small public park alongside it, although in real life the rubbish bins had beer bottles in them and the picnic tables were liberally spotted with dried bird shit. The dull, sparse grass sloped away from her, falling to the level of the next bend in the road. Beyond it, the logo of a service station glowed bright against the dark sky. Directly opposite was a row of squat terraced houses bookended by two pubs. One of them was perfect Instagram fodder, the other was in dire need of knocking down.

Next to the picturesque pub was the mouth of a small road. Natalie could see a giant pothole at its start, concrete crumbling at its edges, the crater filled with murky water. When she lifted her eyes, she saw a cardboard sign had been tacked to the nearest telephone pole: SHANAMORE COTTAGES, 1KM. It pointed down the potholed road.

Everything else in her eyeline was hedge or tree or sky.

The light was fading. Natalie didn’t wear a watch but she figured she’d turned off her phone ten minutes ago, at the most, and it had been just after five o’clock then. She needed to get to the cottages before it got actually dark.

She set off, pulling her case behind her.

Plastic wheels against crumbling tarmacadam produced a hollow, rumbling noise. In the dead quiet, the noise she was making seemed to grow louder and louder. At least, she thought, the road was relatively straight, so any oncoming cars would see her before they hit her – she hoped.

When Natalie finally spotted the sign marking the entrance to Shanamore Cottages, she guessed it was fifteen minutes since she’d got off the bus. Pretty much the length of the walk that Google Maps had promised, then. The cottages, however, were not entirely as advertised.

Individually, the six of them were identifiable from the images she’d seen online. Which is to say, they didn’t look much like cottages at all. Each one was an identical assembly of cubes. Some smooth, unpainted cement and some thick, green-ish glass. The smallest cube was the entranceway, a space about the size of two telephone boxes, where the only non-glass piece was the wooden slab of a front door. A larger cube behind it formed the home’s ground level, with mini cubes making a couple of postmodern bay windows, one at the front and one at the side. Another cube half its size formed the second storey, pushed a few feet to the rear. The entire front section of that cube – the master bedroom, from what Natalie remembered of the website – was made of glass.

But it was obvious now that the photos online had been taken at carefully considered angles. Their frames had conveniently omitted the breeze-block shell of an unfinished McMansion sitting in the overgrown field next door, and they didn’t convey at all just how close together the cottages were. They were sitting in two rows of three, facing each other, with only the narrowest of laneways separating each one from its immediate neighbour. Natalie suspected that if you stood in one of those lanes and stretched your arms out, you’d touch a cottage on each side. She’d found an old newspaper article online, property section, which suggested these were the work of an ambitious young architect who’d qualified at the height of the Boom and had been gifted a swathe of Daddy’s land. Crowding it with cottages must have been him trying to get as much bang for his buck as he could. If that was his plan, it hadn’t worked. The cottages had stood empty for years, no buyer willing to be the first, until some foreign investment firm had bought the lot for a song and turned the entire estate into a holiday ‘village’ of short-term lets instead.

Movement.

A man had emerged from the nearest cottage and was striding towards her. The house had a sign in the front window that Natalie couldn’t read in the dim but she thought it might say RECEPTION.

He waved, called out, ‘Marie?’

He must be Andrew, the manager.

Natalie waved back. ‘That’s me.’

Marie was her middle name. She’d made the booking over the phone just a few hours ago, giving her first name as Marie and her last as Kerr – Mike’s last name, her married one, which she never used. If she had to produce a credit card now or show some photo ID the jig would be up, but maybe the check-in procedure at Shanamore Cottages was more of a casual operation. She’d only needed to give a name and a telephone number to secure her reservation, after all.

There was a red hatchback sitting in Andrew’s driveway and he met her at its rear. The car’s licence plate was almost completely obscured by a thick layer of dried mud.

‘Welcome to Shanamore,’ he said.

It had a streak of apology in it.

They shook hands, limply, Natalie conscious of the fact that hers was warm and damp from dragging her case.

Andrew was wearing dark corduroy trousers and a thick, Aran-style sweater that seemed much too big for his wiry frame; he gripped the too-long cuffs of it in his palms with the tips of his fingers. His dark hair was long and flopped in front of his eyes, the kind of style the boys at school used to have back when Natalie was in it. (Curtains? Isn’t that what they called it?) It all conspired to create a first impression of youth and boyishness but here, up close, Natalie could see that this man was easily her age, late twenties, early thirties.

‘You found us all right?’ he asked.

‘No problem at all.’

He looked around, behind her. ‘You didn’t walk here?’

‘Only up the road,’ she said. ‘The bus dropped me off by The Kiln.’

‘You’ve been here before? To Shanamore?’

‘No, never.’

‘And you’re not here to make pottery – right?’

He’d already asked her this on the phone. There was a local potter who offered week-long classes and had some arrangement whereby attendees got a discount if they stayed here.

‘No.’ Natalie smiled. ‘I’m just after a few days’ peace and quiet, that’s all.’

‘Well, let me show you to your cottage.’

They started walking, him leading the way.

‘You live on site?’ she asked.

‘Yep.’

‘All year round?’

‘All year round.’

‘And you said on the phone you only keep one or two of these open at this time of the year?’

‘It’s easier that way,’ Andrew said. ‘Makes more sense.’

‘So can I ask which one …?’

Andrew pulled a key from his pocket and held it up to the light. It had a large ‘6’ printed on its plastic tag.

Natalie tried to keep her expression neutral while her entire body flooded with relief.

_________

She didn’t know what she would’ve done if he’d shown her to a different cottage. She’d had vague notions of finding a way to get inside No. 6 by other means, later, or making up some complaint that would necessitate a move there first thing in the morning. But mostly she’d tried to not worry about this detail. Now, finally, she could stop.

No. 6 was the cottage directly opposite Andrew’s, No. 1. He unlocked the front door and hurried inside ahead of her. There was no hall or foyer; you were immediately in the living room, facing the foot of the stairs. The entire ground floor of the cottage was one big, open space.

‘Meant to do this earlier,’ he muttered as he scurried about the room, turning on lights. Two floor lamps, the pendant hanging over the dining table, spots recessed in the ceiling positioned strategically over faded prints of Shanamore Strand in cheap IKEA frames. He pushed a button and transformed the pane of black glass stuck low on the (fake) chimney breast into a scene of (fake) glowing fire. He fiddled with the thermostat until the nearest radiator started to splutter and click. Plumped a sofa cushion. Straightened the coffee table.

Natalie stepped inside, closing the door behind her, and watched him move around the room. He reminded her of an air steward in the galley before trolley service: practised to the point of automation.

‘Oh,’ he said suddenly, ‘I forgot your welcome basket.’

Before Natalie could respond, he was gone and the front door was closing with a thunk for the second time in as many minutes.

She parked her suitcase and advanced into the room.

Two three-seater black leather couches and a matching armchair were arranged in a U-shape around the fire and the flat-screen TV that hung above it. Behind the furthest couch, at the rear of the ground floor, was a solid wood dining table with space for eight and beyond that, the clinically white cabinets of an ultra-modern kitchen. Their glossy finish made them gleam in the lights.

The only walls were the exterior ones. The one at the rear was made entirely of glass, a huge window with one door inset. The staircase clung to the side wall and had only air between its steps and no railing; Natalie felt nervous just looking at it. Floor-toceiling windows interrupted the remaining two walls. It was dark enough outside now for all the glass to be showing only interior reflections.

Natalie touched a hand to one of the cushions on the armchair and felt cold with a hint of damp.

And a lump forming in her throat.

A squeeze of heartbreak in her chest.

This can’t be the place … Can it?

The door swung open. Andrew was back, carrying a small wicker basket. The air swirled and changed, suddenly charged with the presence of another person, chilled with the draught the open door was letting in.

He looked at her, eyebrows raised, awaiting a verdict.

‘It’s nice,’ she said. ‘Lovely.’

‘Good. Glad you like it. Sorry about the cold. I should’ve put on the heating earlier. It should warm up pretty quick.’ He set the basket on the coffee table. ‘So – any questions?’

‘No, no. I think I’m all set.’

She smiled. His eyes met hers and she realised it was for the first time. Eye contact, evidently, wasn’t his thing. Andrew proved this by looking away again almost immediately.

Then he gave a little wave, turned on his heel and left.

The thunk of the front door locking shut echoed around the house again and then everything was quiet and still.

Too quiet and still.

Natalie cast about for a remote control but couldn’t find one, so she went to the TV and randomly pressed the slim buttons hidden on its side until loud voices boomed into the space, banishing the silence.

She took a quick inventory of the contents of the wicker basket. A box of Irish soda bread mix; six mismatched eggs; a bag of Cork Coffee Roaster’s ‘Rebel’ blend; a bar of chocolate with a pencil sketch of Shanamore Strand on the label; a single bottle of beer from the Franciscan Well; a small carton of milk.

She was patting her coat pockets for the hard shape of her phone before she even realised she was doing it. It was like a muscle memory, a tic. But she didn’t need a photo of the basket. She didn’t need any photos at all, because she wouldn’t be posting online about this trip.

For a change.

A search of the kitchen turned up a drawer filled with things swiped but not consumed by previous guests: hardened sachets of salt and pepper, a few pouches of ketchup and mayonnaise, individually wrapped teabags.

Natalie supposed she could bake the bread and have it toasted with scrambled eggs, but she was missing a crucial ingredient: being arsed enough to. She wasn’t even hungry, not really. So she made herself a cup of hot, sweet tea and took it to one of the couches, and idly ate her way through the chocolate bar square by square without even taking off her coat.

What she was really doing, she knew, was stalling. Putting off going upstairs. Because being here in the cottage was one thing, but to see the bed, to have to – at some point – get into it …

On the TV, the talk show had been replaced by a Friends rerun. The one with the wedding dresses.

By the time Phoebe and Monica had persuaded Rachel to get into one too, it was pitch black outside.

Natalie got up to draw the curtains.

According to the front window there was nothing out there in the night except for a buttery gold square directly opposite: a view into Andrew’s living room via the window at the front of his cottage. Same layout, same furniture, just all turned the other way around like a mirror image. There was no sign of him and no lights on upstairs, although his car was still parked in the drive.

She pulled the curtains closed until their edges overlapped. The material was thin, the orbs of the streetlights easily filtering through.

There was nothing to cover the wall of black glass, yawning like the mouth of a great abyss at the rear of the cottage. Either the owners were trying to save money or they thought there was no need for window dressings when all that was behind the house was a patio, a few feet of communal garden and a hedgerow. But it made Natalie uneasy. What was on the other side of that hedge? She couldn’t tell in the dark.

There could be another house looking directly into hers.

There could be someone looking at her right now.

As Natalie stood at the glass, contemplating this, it morphed from a mere lack of privacy into a structural vulnerability. How strong was that glass? Could someone hurl a rock through it? What would she do if someone did?

Here it comes, she thought. The Anxiety Train. Express service to Crazytown unless she applied the brakes. Natalie tried to, now, telling herself that the glass was fine and that there was no one out there. That hundreds if not thousands of people had stayed in Shanamore Cottages before her and nothing had happened to any of them. That if it were daytime, she wouldn’t even have noticed this. This wouldn’t even be a thing.

She silently repeated this several times until she felt herself relax.

But she also wished she’d found a bottle of wine in that bloody wicker basket.

It was when she turned to go back to the couch that the shelf beneath the coffee table revealed itself and the several small piles of books on it. Natalie knelt on the floor and started pulling them out, appraising each one. Battered paperbacks. Airport bestsellers, for the most part. A newish copy of Jurassic Park. Two or three in a foreign language.

A library of left-behind holiday reads.

Natalie stopped and stared at the narrow, hard, cornflower-blue spine.

And she knew. She knew even before she reached out and picked it up and turned it over in her hands: it wasn’t just a copy of Percy Bysshe Shelley selected by Fiona Sampson. It was her copy.

Their copy, hers and Mike’s.

Then she opened it and got confirmation.

Stuck on the first page was the bookplate she’d bought in the Keats–Shelley House by the Spanish Steps, along with the book itself, a few years before. It was stuck on slightly askew because Natalie had done it quickly, surreptitiously, in the doorway of the gift shop, before Mike could catch her in the act. The For my M she’d scrawled beneath the sticker was in a messy version of her handwriting for the same reason. When she’d presented it to him that night over a candlelit dinner off the Via Veneto, the first thing he’d said was, ‘When did you buy this?’ The next question he’d asked her was if she’d marry him, the proposal his plan for their supposedly last-minute weekend away in Rome all along.

Last week she’d been arranging the bookshelves in the room she was supposed to be using as a home office when it had occurred to her that she hadn’t seen that book in a while. When she’d asked him about it, Mike had reminded her that there were a few things they hadn’t seen since the move. He’d said it was probably down the bottom of a box they hadn’t unpacked yet. He’d seemed confident that it would show up soon.

Natalie clutched the book to her chest as if it were something precious. And it was, but not for the reasons it had been in the past.

Now, it was evidence.

Now, she had proof.

_________

The clock on the TV screen said it was almost eight. Natalie decided to have a bath. It would warm her up and give the cottage time to warm up too. Afterwards, she’d crawl into bed and let herself sink into a night of blissful sleep. She could face facts tomorrow.

She’d have to face the bed now, though.

Reluctant to put the poetry book back with the others or to leave it out, Natalie pulled open drawers in the kitchen until she found a relatively empty one and then slipped it in there. After double-checking the doors and windows were locked, she turned out the living-room lights and lugged her case up the stairs. She kept her free hand on the wall to steady herself and tried not to focus on the empty space between the steps or the yawning open space to the right of them.

There were two closed doors at the top, one off either side of the small, carpeted landing. The bathroom was through the one on the right. Simple, white and very clean. There were no windows save for a tiny frosted square above the sink. Natalie dropped the plug in the bath and ran the tap until it got hot, adding a few drops from the miniature bottle of shower gel that had been left on the edge.

She sat on the closed lid of the toilet and watched the bubbles grow.

Until an alien noise pierced the air.

BEEP-BEEP-BEEP-BEEP-BEEP.

Her phone, Natalie realised on a delay.

Had it always been that loud? And that annoying? She got up to retrieve it from her bag, which she’d dropped in the doorway. A single bar of service had appeared on screen, letting a flood of text messages and notifications come through. The newest one said she had a voicemail.

Natalie put the phone to her ear and played it.

It was him.

‘Nat, where are you? What’s going on? I’m—’

She threw the phone across the room and watched as it smacked off the tiled wall, dropped into the bath water and sank beneath the bubbles.

Natalie blinked.

Had she really just done that?

She’d done it unthinkingly, or rather before she could think about it, and now, in the moment immediately after, she felt like she might throw up.

No phone? The idea made her feel clammy, anxious, unmoored. No phone. No phone. No phone. She couldn’t contact anyone and no one could contact her. No one even knew where she was—

But that had been her plan, hadn’t it? She had intended to turn off the phone while she was here. This would make things easier now. Simpler. She wouldn’t be able to turn it back on, so she wouldn’t need to waste any energy trying to stop herself from doing it.

This was a good thing, even if it didn’t feel that way.

Natalie found the phone beneath the water – the screen, somehow, had remained intact – and put it in the plastic bin under the sink.

The bath wasn’t full yet. She pictured herself lying in there with the breach of the bedroom still ahead of her and decided that wasn’t the right recipe for relaxation. She should go in there now. Just get it over with.

It was only a bed, for God’s sake. An inanimate piece of furniture.

She crossed the landing.

The bedroom was cold with a hint of damp, just like downstairs, and just like downstairs, this space had a gaping wall of glass. The difference was that this one was to the front of the cottage.

There was an amber streetlight right outside and it lit the room well enough to see the outlines of everything in it, but Natalie flicked on the ceiling light to get a better look. The bed was king-sized, the sheets plain white and pulled smooth across the mattress. She got down on her hands and knees to look underneath it, imagining that she’d see the glint of a cufflink or a lost earring, like people do in the movies.

There was nothing.

It didn’t matter. She had the poetry book.

The bed faced built-in wardrobes with mirrored doors. There was a dressing table, a small TV screen mounted on the wall and a table and two tub-style armchairs set right in front of the wall of glass, just in case you wanted to play a game of Exhibit in a Zoo.

This wall of glass, at least, had curtains. Natalie was pulling them closed when she caught a flicker of movement in her peripheral vision: someone moving in the downstairs window of Andrew’s cottage. But when she looked, there was no one there.

She wondered what Andrew’s deal was. Was he from Shanamore? Did he live alone over there? She hadn’t seen a wedding ring or any evidence of children. And there was something about him, something she couldn’t quite articulate, that made it hard for her to believe he wasn’t alone and easy to assume that he was.

The wall of black glass that fronted the second storey of Andrew’s cottage – his bedroom window – suddenly lit up with a flash of eerie blue light, revealing—

A woman.

Standing at the window, looking out.

Natalie yanked the curtains closed, then immediately regretted being so obvious about it.

There’d barely been time to collect an impression but it was definitely a woman she’d seen, not Andrew. She was wearing a skirt. Knee-length, maybe. And her hair was pulled back from her face, perhaps in a ponytail …

‘No,’ Natalie said aloud, catching herself. Don’t start down that road. She’d only seen this woman for a fraction of second; she couldn’t describe her in any detail with any certainty. And she didn’t think she’d been wearing glasses. The light that revealed her was so odd, it was as if she was lit from the chest up—

Natalie realised what the weird blue light had been, where it had been coming from.

The woman’s phone.

That had been all the light, which meant that until some call or message had lit up that phone’s screen, that woman had just been standing there in total darkness, at the window, in Andrew’s bedroom.

Watching.

Watching Natalie.

Three loud knocks, knuckles on a door.

‘Audrey?’ a voice said. ‘You up?’

She wasn’t. Audrey was half-awake, aware of real-world intrusions but desperate to hang on to the warm, wispy tendrils of sleep, to delay another morning for just a few moments more.

She clamped her eyelids shut, turned over and burrowed deeper into the warm cocoon of her bed.

‘Aud?’ Louder now, more demanding: ‘Audrey?’

The voice was coming from the other side of the bedroom door, the handle of which wasn’t a full foot from Audrey’s head. It belonged to Dee, her younger sister.

And, technically speaking, her current landlord.

‘I’m coming in,’ Dee warned. But this was followed by a clink and a dull thump; she’d tried the door and discovered that it was locked. ‘Audrey, for God’s sake. Open this bloody door before I have to—’

Audrey reached out an arm and turned the key in the lock.

The door swung open immediately, the white light from the landing banishing the grey dim of the box room in one fell swoop.

The next thing Audrey saw was a cup of steaming coffee seemingly hovering in mid-air.

‘Is that for me?’

‘It wasn’t,’ Dee said. ‘But you can have it.’

Audrey pulled herself into a half-sitting position and gratefully took the cup of coffee, slurping up a mouthful.

She stole a sideways glance at her sister as she did. Dee was standing in the doorway, arms folded, surveying the roomscape with a frown. She was already dressed for work in her trademark black suit, barely there make-up and neat, gleaming hair; Audrey so rarely saw her in casual clothes these days that whenever she did, it was disorientating, like meeting one of your primary-school teachers outside of school.

‘It looks a lot worse than it is,’ Audrey said.

The box room was a small square narrowed by a set of built-in wardrobes along one wall and the single bed pushed against the opposite one. The strip of floor that remained was mostly hidden by a thick layer, several strata deep, of books, clothes, papers. The bad news for Audrey was that this mess matched up perfectly with the shaft of bright light coming from the open door, an unwelcome Newgrange.

‘What amazes me,’ Dee said, ‘is how quickly it descends into this.’

‘An almost thirty-year-old shouldn’t be able to fit into a space this size. It’d be weird if it didn’t look like this, if you ask me.’

‘Speaking of—’

‘Jesus, Dee,’ Audrey said, ‘I am not having a party. How many more times—’

‘We’ve accepted an offer, Aud. As of ten minutes ago. Five grand above the asking price, which is more than we thought we’d get. Especially after all this time.’

Audrey’s stomach sank.

She said, ‘That’s great. Wow. Congratulations.’

‘Thank you.’ Dee smiled briefly. ‘It is great, yeah. But it comes with a condition. The buyers’ own house is already sold and their buyer is anxious to move in, so they want to move in here, like, yesterday. We’ve, ah … We’ve agreed to be out in three weeks.’

‘Three weeks?’

‘I know, it’s a bit crazy.’

‘But you haven’t found a house yet – have you?’

‘No, not yet.’ Dee touched a hand to the doorframe and then turned to look at where her fingers had landed, as if fascinated by some imperfection in the wood she’d just detected there. ‘Alan and I … We can stay with his parents. They’ve offered us their spare room.’

‘Oh.’

‘Maybe there’s a friend you can stay with, just until—’

‘Don’t worry about it,’ Audrey said. ‘I’ll sort something out.’

‘I’ll ask around at work. Maybe you could get a room-share. And if you need help with a deposit—’

Audrey reflexively raised a hand in a stop gesture, silencing Dee. She didn’t want to talk about borrowing money from her little sister two weeks before her own thirtieth birthday. Their living situation was shameful enough.

‘I’ll be fine. Anyway …’ Audrey threw back the blankets and swung her legs out of bed. ‘I better get going. What time is it?’

‘You know,’ Dee said, ‘I think this is actually going to be a good thing.’

Audrey felt the aftertaste of the coffee turn bitter on her tongue.

‘I wanted to help you,’ Dee continued, ‘but I don’t think I was helping you. That’s the thing. You’re just not— I mean, you never were—’

‘Hungry enough,’ Audrey finished. She’d heard the same line from Dee umpteen times before. ‘Because I’m just too comfortable, aren’t I? I need to struggle. Well’ – she stood up, thrusting the coffee cup back at Dee who only narrowly avoided getting her white shirt flecked with coffee drops – ‘in three weeks I’ll be homeless and destitute, so that should probably do it, don’t you think?’

Dee rolled her eyes. ‘Oh, come on.’

‘No, no. You’re right. You’re totally right.’ Audrey began angrily smoothing the pillows and pulling the corners of the duvet to the edges of the bed. ‘I’m just way too comfortable here, living in the ten square feet my little sister rented to me, doing a job that’s, like, a million miles away from the one I want to have, working forty hours a week just to pay off a loan I took out to get a Masters that, so far, has been of absolutely no use to me at all. While also slowly dying of shame. Yep, you’re absolutely right.’ She stopped and turned to face her sister. ‘I’ve got it cushy.’

‘You just don’t want to hear the truth. You never have. Because, God forbid, it interferes with your dreams and mantras and your vision boards.’

‘What’s your point, Dee? That I’m a great big failure? Is that it?’

‘I don’t think you can fail if you’ve never even tried.’

‘You should put that on a poster. One of those motivational ones. With a sunset. You could sell them on Etsy. You’d make a fortune.’

‘Aud, you—’

‘I am trying, Dee. I have been trying. All this time. As hard as I possibly can.’

‘Have you?’

‘Yes.’

Dee held out her left arm and rotated it until Audrey could see the face of her slim, silver watch.

Audrey blinked at it. ‘Oh, for …’

She’d overslept.

She was an hour late for work and counting.

_________

By skipping a shower and taking a cab she could ill afford, Audrey made it to the office just in time for what they called the ‘Now’ meeting, held every morning at nine thirty. ThePaper.ie was run out of Hive, a trendy open-plan co-working space off Leeson Street that was populated with beanbags in primary colours, complimentary fruit water stations and men who dressed for their cycle to work as they would for the Tour de France.

The rest of the Ents team were already gathered around AltaVista, a giant slab of a conference table named after an early internet search engine. Audrey was confident that she was the only member of the team who knew what AltaVista actually was. The rest of them would probably keel over if they knew she was old enough to have used it.

Everyone was heads down, their eyes fixed on their phones. Audrey slipped into one of two vacant seats – the other one, at the head of the table, awaited the imminent arrival of their boss, Joel – and took out her phone too.

She had a new email. It was from Joel, a master of devastating brevity. The message consisted of only one word. All caps, no punctuation.

LATE

It had been sent three minutes ago. Audrey wanted to twist in her seat and see where Joel was watching them from, but if he’d seen her come in, he’d see her do that too. Besides, it was no mystery. His vantage point was most likely his office, a tiny box made entirely of glass partitions, parked in the middle of Level 1. His very own Panopticon.

Audrey deleted the email and swiped at her phone’s screen until Daft, the property-search app, had started downloading itself to the device.

Three weeks. She had three weeks to find a place she could afford that didn’t also look like it had been a drug den in a previous life or had the potential to be a crime scene at some point in the future. Audrey knew what was ahead of her; she’d seen the TV documentaries, read the reports. Professionals sleeping in bunk-beds. Bedsits that offered the convenience of being able to work the microwave without having to get off the toilet. A queue of fifty-odd twenty-somethings waiting obediently outside every half-decent listing, eyeing up their competition, trying to assess where they were likely to come in this latest round of Dublin’s Private Tenancy Pageant, founded in 1999 and back now, bigger than ever, after a little devastating-economic-downturn break that was already fading from everyone’s memories. Audrey did some mental arithmetic and then entered what she thought she could stretch to, rent-wise, in the Search box. The only result was a single bedroom in a house in Stillorgan. There were no photos at all, which probably meant the place looked like an episode of Hoarders featuring Fred and Rosemary West. Yet in the five days since the listing had gone up, it had been viewed almost fifteen thousand times.

‘Morning all.’

Joel had appeared as if from nowhere, like he did every morning. The man didn’t arrive so much as materialise.

Audrey slipped the phone into her pocket and waited to catch his eye so she could mouth a sorry at him but, before she could, he said her name, sending a ripple of interest running around the table like an electrical current. Then:

‘My office. Straight after this.’

Audrey just about managed a weak nod of acknowledgement. She’d never been called into his office before. She must really be in trouble.

‘Right,’ Joel said then, loudly, signalling the meeting’s start. ‘Everybody ready?’ He sat down and flipped open his laptop, tapped a key and started reading from the screen. ‘Here’s what we’ve got so far. Rumour has it there’s a snap of a certain rugby star and a certain girlfriend of another certain rugby star getting up to no good in The Grayson on Saturday night. Snap as in Snapchat. Find it for me. That’s our top priority. Across the pond: Lena got a tattoo with no bra on and some magazine has a video of it. Embed is our friend. Across the other, smaller pond: Piers thinks KK shouldn’t have used a Snapchat filter on O’Hare, so we have the snap and we have a screen-grab from the show there. That’s two paras already and you haven’t even had to make anything up yet. Fresh in from the paps: some actress going somewhere with no make-up on. One of the models going somewhere with not enough make-up on. An X-Factor reject going somewhere with lots of make-up on. Danni, I’m going to give those last three to you.’

Danielle, sitting directly across from Audrey, lifted a flattened hand to her forehead in a mock military salute. She was the team’s MVP when it came to coming up with different angles on Woman Somewhere On Celebrity Spectrum Goes About Her Daily Life. For Christmas last year, they’d got her a T-shirt with STEPS OUT AMID, her favourite phrase, printed on the front.

‘And we’re trying something new this week,’ Joel continued. ‘Find someone interesting, scour the ’Gram for shots taken at home with lots of background and use them to flesh out “Inside the home of …” pieces. Our angle should be “this person clearly gets paid way too much of the licence fee because look how swanky their home is despite them being utterly shit” or “secret shame of the washed-up former star forced to live in a three-bed semi”. Okay?’

Audrey nodded along absently with the other bobbing heads. Her mind had started to wander. What was she going to say to Joel? He always seemed to expect more of her than he did of the others, presumably because she was older, more mature, more sensible, and on every other day she appreciated that distinction. But now she feared it might mean she was in actual trouble for a silly infraction.

It was excruciating to care about something that mattered so little. Audrey didn’t know which was worse: having to do this job or the prospect of losing it.

The Paper was an online news site that had started life as a content aggregating upstart during the Celtic Tiger, when Ireland suddenly got money and discovered feta cheese and flat whites and investment properties in Bulgaria and everyone collectively lost their minds. But the arrival of the Bust coincided with the arrival of the smartphone and, after pivoting away from its original website into an app and mobile offering, The Paper had survived – and thrived. It now employed a team of reporters who wrote original pieces and broke actual news in 250-word Lean Cuisine-style stories, just the right portion size for the eternally distracted Millennial scrolling through his phone while in line for a burrito bowl.

The problem was that Audrey wasn’t one of those reporters. Her job was in The Paper’s entertainment section, infamous for doing the opposite of their Serious News colleagues upstairs: squeezing 250 words out of nothing of import at all. Usually a single, pixelated paparazzi shot and an allusion to some unsubstantiated rumours that just about stayed within the legal lines. Their model was the universally despised but yet also phenomenally successful Sidebar of Shame. They worked to traffic targets – clicks – set by the Powers That Be each morning. Every minute counted and every story had to pull its weight. It was the only position a newly graduated and totally inexperienced Audrey was offered that was even remotely related to what she wanted to do. What she’d decided to finally try to do, aged twenty-eight, after nearly a decade in recruitment.

What she really wanted was only one floor away: the rest of The Paper’s staff, the ones who wrote about the actual news, had the whole of Level 2, upstairs.

Audrey would get there.

That was the plan.

And so, for now, she would suck it up. She would spend her days coming up with different ways to say ‘Famous woman goes outside, does mundane things’ and she would do it well. She would bide her time until an opportunity arose.

That’s what Dee didn’t understand, that waiting was trying.

Snap.

Joel had closed his laptop.

Audrey had zoned out on half the meeting.

‘Let’s get those clicks,’ he said to the group. Then to her: ‘Let’s go.’

She got up and followed him away from the table.

Joel’s office was so small that the only seat was the one behind his desk, so Audrey stood in the doorway, facing him.

He had barely sat down when she blurted out, ‘I’m so sorry I was late today. I don’t know what happened, but it won’t happen again. I promise.’

‘Good, but this isn’t about that.’ Joel rested his elbows on the desktop. ‘Audrey, I may have a story for you. It’s a bit TMN for us, this …’ TMN was Too Much News, Joel’s shorthand for stories that had some viable content for Ents but mostly involved details their core readership would skim. Like when celebrities made speeches at the United Nations. What they wore: yes, in excruciating detail. What they said: no one cares. ‘But upstairs aren’t interested and I don’t want to let it go to waste. You’d get the by-line. You’d be off the click-factory for the day. And if you strike the right tone – if you can get the balance right – I can probably get it listed on the main page as well as in Ents, so, you know …’ He turned his palms to the ceiling. ‘Actual news.’

‘I’ll do it,’ Audrey said.

Joel snorted. ‘I haven’t told you what it is yet.’

‘Whatever it is, I’ll do it.’

‘I’m sure you will. The question is can you?’ Joel paused. ‘Do you know who Natalie O’Connor is?’

Of all the things Audrey thought he was going to say next, that had been the very last one.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Of her, anyway.’

Audrey wasn’t about to admit it to Joel – or anyone else – but she had spent hours of her life scrolling through Natalie O’Connor’s life on Instagram. Dubliner Natalie was beautiful. Glossy. Perfect. Nice. Living in an Ideal Homes spread and married to a Prince Charming in a non-problematic way. She had thousands of followers and had parlayed her popularity into a lifestyle brand called And Breathe. Its website flogged scented candles made by hard-to-pronounce brands and un-ironically shared articles with titles like ‘Digital Detox: What Happened When I Put Down My Phone and Picked Up My Life’. Since both Natalie O’Connor and Audrey were the same age – since they’d both had the same amount of time to get their lives in order – it was, inevitably, a depressing spectator sport.

What had Natalie done?

Audrey was thinking scandal. A few exposés had hit the blogging world recently. Girls with caterpillar eyebrows getting paid thousands to say beauty products worked when what actually worked was Photoshop. Someone caught pretending a hotel room was the inside of her own home. Becoming the face of a national stop-smoking campaign and then getting pictured on Grafton Street at 3 a.m. lighting a fresh Marlboro off your last one.

‘Natalie is missing,’ Joel said. ‘She’s been missing for a week. And her husband didn’t bother to tell anyone that – including the Gardaí – until today.’

_________

Audrey walked back to AltaVista with her eyes fixed firmly on the floor. She grabbed her coat and laptop bag from her vacated chair, studiously ignoring the searching looks of everyone else still sitting there. Their collective curiosity pulsed in the air like a bass-line, but Audrey wasn’t going to enlighten them. This was her story.

There was a Starbucks five minutes’ walk away and a Starbucks ten minutes’ walk away. In Audrey’s experience, no one from Hive could be bothered to trek to the further one, so it was the perfect place to work undisturbed. She ordered a large filter coffee, the one item at the intersection of lowest price and longest lasting. She was starving but couldn’t stretch to any overpriced, barely defrosted pastries after forking out for that cab this morning, but she thought there might be a half-melted cereal bar thingy in the bottom of her bag if she got desperate. She settled into a low armchair in the far corner of the café’s upper level, her laptop balanced on her knees.

The first thing Audrey did was open a new Word document and copy the text from the Garda press release into its blank white space. It was the standard fare.

Gardaí are appealing for the public’s help in finding a Dublin woman missing since 5 November. Natalie O’Connor, 30, was last seen at her home on Sydney Parade Avenue in Sandymount on Monday 5 November at approximately 8 a.m. O’Connor is described as being 5’5” in height with long brown hair and brown eyes. Anyone with information is asked to contact Donnybrook Garda Station on …

The Paper got sent at least one of these notices from the Garda Press Office every week and only the personal details ever changed. Joel had explained to her that it was largely up to the family of the missing person whether or not to release an appeal like that, so this didn’t mean that the Gardaí were out in their crinkly white overalls combing the Wicklow Mountains for decomposing Natalie parts. Whatever this incident was, it probably fell somewhere on a spectrum between personal crisis and a domestic dispute. This appeal was destined to become one of the thousands of missing person reports Gardaí released each year that were followed a few days later by the good news that the public could stand down. Which was why, for The Paper, this wasn’t really news. But Joel had recognised the name and seen an opportunity.

One hundred thousand of them, to be exact.

That’s how many followers Natalie O’Connor had on Instagram. With no updates from the woman herself, those followers would be desperate for information and they’d look for it in the same place they found everything else: online. If Audrey could come up with a few plausible explanations for Natalie’s week-long disappearance and put them in virtual print without incurring the wrath of the legal department, those 100,000 clicks – and perhaps many more besides – would be theirs.

And Joel would love her for it.

She chugged some coffee and then did a bog-standard Google search for Natalie’s name.

There was less than a page’s worth of relevant results. Two bare-bones news stories from that morning, which were basically the Garda appeal, an old interview about her diet with an Irish glossy magazine and a somewhat snarky article by a broadsheet listing Ireland’s top-ten influencers arranged in descending order by their follower numbers that had been published six months ago.

Behold the strange, self-regulating confinement of Internet fame.

There seemed to be no Twitter account for Natalie and no Facebook profile, at least none that were publicly accessible. Instagram, then, was going to be the start and end of Audrey’s research.

She picked up her phone and tapped on the app’s icon.

Since April 2012, Natalie O’Connor had posted well over 3,000 photographs to Instagram. It took Audrey nine minutes and a very real risk of Repetitive Strain Injury to scroll down to the start of the stream. The posts there were badly lit and often blurry pictures of an entirely different girl altogether.

Natalie the missing person was unfailingly elegant, wearing glowing make-up on perfect skin, sporting shiny raven hair in sleek waves and a wardrobe that was Dry Clean Only. But Natalie from six years ago had over-plucked eyebrows, streaky yellow highlights and a wardrobe of fast fashion that didn’t look like it would survive more than one spin in the wash.

Audrey took a screenshot of the very first post: a selfie of Natalie wearing an ill-fitting mini-dress, taken in a mirror that inadvertently captured a messy bedroom with clothes scattered on the floor and mismatched sheets on an unmade bed.

Scrolling back up, it was easy to track the woman’s transformation. The quality of the photos got better – and Natalie herself started to look better, glossier, more put-together – but what was in the photos changed too. A careful curation set in, gradually narrowing the range of images to just three subjects: places Natalie went, outfits she wore and shots of the inside of her immaculate home.

Mike, her husband, rarely featured in the photos but was often credited with taking them, the perfectly compliant Instagram Husband. He made most of his appearances in a series of shots from their wedding day. Him and Natalie on the shores of some impossibly picturesque lake, every last pixel perfect.

Audrey banked another screenshot: a close-up of the newlyweds gazing adoringly into each other’s eyes, not a pore nor a smudge of make-up or a stray hair in sight.

Then she scrolled back up to the very top. The most recent post was a picture of a grooved, hard-shell suitcase in pastel pink, parked on a hardwood floor in a hallway filled with natural light. A smaller, matching bag was leaning against it and a crimson passport was resting on top of that. The caption read:

Taking a few days to myself. I hate to be one of those insufferable people who tell you they’re taking a break from their phone and social media by posting to social media using their phone, but I don’t want you thinking I’ve mysteriously disappeared. Sometimes I just need to live up to my own brand. Back soon! #outoftheoffice #timeout #andbreathe

Audrey took a screenshot of that too, then moved on to the comments Natalie’s followers had left underneath.

Nice! Enjoy!You deserve it xWhere did you get your case?Omg where are you going?LOVE the suitcase! Where’s it from?