Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

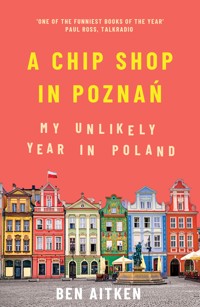

'One of the funniest books of the year' - Paul Ross, talkRADIO WARNING: CONTAINS AN UNLIKELY IMMIGRANT, AN UNSUNG COUNTRY, A BUMPY ROMANCE, SEVERAL SHATTERED PRECONCEPTIONS, TRACES OF INSIGHT, A DOZEN NUNS AND A REFERENDUM. Not many Brits move to Poland to work in a fish and chip shop. Fewer still come back wanting to be a Member of the European Parliament. In 2016 Ben Aitken moved to Poland while he still could. It wasn't love that took him but curiosity: he wanted to know what the Poles in the UK had left behind. He flew to a place he'd never heard of and then accepted a job in a chip shop on the minimum wage. When he wasn't peeling potatoes he was on the road scratching the country's surface: he milked cows with a Eurosceptic farmer; missed the bus to Auschwitz; spent Christmas with complete strangers and went to Gdansk to learn how communism got the chop. By the year's end he had a better sense of what the Poles had turned their backs on - southern mountains, northern beaches, dumplings! - and an uncanny ability to bone cod. This is a candid, funny and offbeat tale of a year as an unlikely immigrant.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my parents, who got me going.

Contents

1

We are here to go somewhere else

8 March 2016. I decided to move to Poland in the sauna. It seemed sensible. I had seen Poles in Peterborough and Portsmouth and the Cotswolds and I had followed the conversation about whether there were too many in the UK or too few, whether they were doing all the work or none at all. I wanted to know why the Poles – a notoriously patriotic people – were leaving home in their millions. I am also contrary by nature and design, so the idea of going the other way, of being a British immigrant in Poland, was appealing. Also appealing was the idea of being elsewhere. I had grown tired of Great Britain. Its comforts were a pain. Its nice routines were doing nothing for me. I wanted to be alone and abroad and innocent and curious, to have my character reset, my faults unknown, to find stories in buildings, stories in people, to be childish once more, to be again at the beginning. Moving to Poland is not the only way to deal with a case of itchy feet. I might have moved to the Falkland Islands. But if Britain chooses to leave the European Union in three months’ time (a referendum is in the diary) my freedom to move and work and love and learn in twenty-odd countries will be irrevocably lost. Make hay while the sun shines.

Four days after the sauna I flew to Poznań. I chose Poznań because I had never heard of the place and it was the cheapest flight. I didn’t want to move to Warsaw or Krakow, where there would be plenty of English speakers. I’d had enough of those. A friend had been on a stag do in Krakow. He was able to consume things that were pronounceable, to take trams and taxis in the right direction, to convince a pair of police officers he had no idea throwing kebab meat at the statue of a Nobel Prize winner wasn’t de rigueur. (Despite all their practice, the British don’t travel well.) He did all these things in English, of course. Polish wasn’t necessary to get by. I didn’t want that cushion. If I was caught throwing fast food at a national treasure, I would like to defend myself in the local tongue. It would show respect. In short, I wanted to feel that I was fully elsewhere. I wanted to be an alien. ‘We are here to go somewhere else,’ said the writer Geoff Dyer.

Eastern Energy, Western Style it says in baggage reclaim. What does that even mean? Is Poland on the fence? Is it caught in two minds? Poland was a communist country for 50 years until the early 90s, under the thumb of Russia. It was forced to look east. But now what? I don’t have anything to reclaim – or claim for that matter – so spend time in front of touchscreen info-points that issue warnings and invitations. The city is its brands, says the screen, before showing a list of popular retailers. West, indeed.

On the 59 bus I see international brands like old foes, with their inevitable flags and packaging, then a World Trade Centre, squat and beige and laughably low-key, a mile shorter than the one that famously fell. Then endless residential blocks in lime and butter, mint and pink, colour an apology for form, stubbornly stretching along Bukowska Street. The bus’s upholstery and layout and adverts beg questions. Simple things, suddenly odd. There is nothing remarkable about the bus or the journey, and yet I am transfixed. A slideshow of paintings by Delacroix and Hockney, of peasants and swimming pools, couldn’t hold my attention more tightly. And so it starts, I think, the endless enquiries of the uprooted, the keen eyes of the replaced. I am delighted to feel the questions come on, after months of stale thinking at home, that well-loved place that I often long for, but more often long to betray. Oikophobia is a chronic inclination to leave home. I’m a first-class oik. Home is Clive Road, Portsmouth, England, Britain. Portsmouth was built to build ships that no longer need building. Charles Dickens was born there but moved to London when he was five, already tired of the place. The football club and the sea give people something to look at. That’s all you need to know about home.

If ignorance is bliss then I’m in for a good time. I know absolutely nobody in Poland and know nothing of the language. Is it the Roman alphabet? Is there even an alphabet? Perhaps the alphabet was destroyed in the war, along with the rest of the country. In any case, moving to Poland will be rejuvenating. If I work hard over the next year, I’ll be able to speak Polish as well as a three year old. The idea appeals to me. Three year olds are some of the happiest people I know. My niece is three. She’s ecstatic. She gets a thrill out of the simplest of things, like waking up or tying her laces. Maybe being effectively three won’t be such a bad thing. Maybe it will teach me a few things. There is much said or written about travel improving or stretching a person. ‘Didn’t she grow!’ they say. Less is said of travel reducing a person, infantilising them, making a child of them, and how it does them a service thereby.

Even an innocent needs to break the ice. I had bought a phrase book at the airport in London, had committed a few phrases to heart over Germany. By the time I landed I knew how to say ‘I love you’, that I am ‘happy’ or ‘sad’, that something is ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’. I would live a binary existence, a yes-or-no lifestyle (not unfashionable these days), surely preferable to a life on the fence, to considering all things alright. It would be liberating to leave such a linguistic centre-ground, such a diplomatic no man’s land. I look forward to tapping a stranger on the shoulder and pointing to a child riding a bike for the first time and saying, ‘That is not ugly, I love you.’

The bus terminates outside Planet Alcohol and Mr Kebab. Scanning around for bearings, it is apparent that Polish words are longer than average. Most look like Wi-Fi passwords, anagrams to be unscrambled, encryptions to be cracked. No wonder that a lot of the groundwork for the Enigma codebreaking machine was done by Poles. Untangling is in the genes. One of the reasons that Poland’s economy is notoriously sluggish, I would like to think, is because everyone is staring at memos and instructions and agendas and emails wondering what on God’s earth is meant by them.1 There is no two ways about it, it will be a hard language to learn. Not only must I learn new letters – e and a and o and s and c have alternatives that are accessorised with tails and fringes – but I must also contend with familiar letters arranged in new ways, with the result that when one finds oneself in front of a door, and is invited to pchać, one doesn’t know whether to push or pull. Moreover, faced with such an impassable door, such a language barrier, one is unable to ask a passer-by to clarify the situation, for their instruction – ‘Push it and see, you immigrant!’ – is bound to be equally senseless. An alien in Poland, therefore, can reliably be found stranded before some portal or another, wishing (in English) that it were automated.

I check in at a hotel on Freedom Square then go to a nearby information point. The women at the information point can’t answer my questions about registration, health insurance, benefits. They don’t seem able to deal with someone long-term. ‘But when are you going home?’ they ask. ‘When does your holiday end?’ What they can tell me is where a bank is. I go there for a short interview, during which I’m offered coffee and a translator. If this is the face of Polish bureaucracy, it’s a face I could get used to. It wasn’t always thus. Michael Moran was not offered coffee. By his account – A Country in the Moon, which remembers the author’s time helping Poland convert to capitalism in the early 90s – it took Michael seven months to post a letter. ‘A country in the moon’ refers to a remark made by Edmund Burke at the end of the 18th century, when Poland was taken off the map by Austria and Russia and Prussia, and then put on the moon, where it remained until 1919. It was an extraordinary historical circumstance, an exceptional vanishing act, a momentous dislocation. I bet the Polish people remember the moon days keenly.

9 March. I eat dumplings in a park near the hotel. They are either ugly or beautiful, I can’t decide. The park is named after Chopin. There is a bust of the composer on a flint pedestal. An ear is missing. A team of high-brow pigeons have had it for lunch. I think of that poem by Shelley or Byron about Ozymandias, about legacy and mortality, and wonder if Chopin wrote music in order to be remembered, to be set in stone and planted in a park where students come to snack and slumber. I can be glib about motives. I can say I came to Poland because the flight was cheap and I fancied a change. My fundamental motives are less glib. To write a book, to write anything, is an attempt to be less dead. I move and write because those things are essential to me. I could go without many things in life – toast, sex, Canada – but I don’t think I could go without travel and words.

Being of working-class stock, I am drawn to a bar called Proletariat. I shan’t tell you the street name because if I did you’d accuse me of using difficult words for the sake of it. The barman must have seen me outside looking at the door and wondering what to do with it, for he issues an English menu before I’ve chance to say anything. The bar is decorated with busts of Lenin and Chairman Mao, portraits of Marx and Engels and Russell Brand, whose recent book Revolution has inspired a million people to stop reading books. I would like to think that the talk at neighbouring tables is of revolting peasants and meaningful social change, but I suspect it isn’t. It is a young crowd, affluent looking. They don’t seem the revolting type. What they do seem is eager to be branded – New Balance trainers are part of the youthful uniform. They cost the same as they would in the UK, 350 zloty a pair, about £70. To earn that sum here one must work a low-wage job for a week, the minimum wage being roughly 8 zloty. I am starting to understand what was meant by Western Style, Eastern Energy. Poles must work thrice the hours to wear the same trainers. The iron curtain was drawn back and onto the stage came a company of trademarks, each ready to impress, to make their mark.

I find the old market square, faithfully repaired after being squashed in the war. I don’t try to put my finger on the buildings – to label the gables, spot the styles. The buildings may bear signs of stucco or rococo or art nouveau but what of it? The beauty of this old square is too obvious to invite further analysis. The detail is beside the point. How is it beautiful? is not a question we often ask or answer. At any rate, I am invited by a girl with a red umbrella to watch 22 beautiful girls at Euphoria. But it is only the afternoon, I point out. That is not a problem, she says. The girls don’t mind. Desire doesn’t rest. I can drink a coffee or tea if I wish. Twenty-two, she repeats, as if one either side would make all the difference.

I resist Euphoria, enter a pub called The Londoner, already attracted to the idea of return. I sit with an imported ale, beneath images of Big Ben and Tower Bridge, mounted encouragements to try Kilkenny, to give London Pride a go. I’ve never been anywhere like it. I ask a young man if he speaks English. Of course, he says. I ask an old man if he speaks English. He just points out the window. Outside the bar, beneath the ornate clock tower of the town hall, I talk with Alfie from Norway and Emre from Turkey. They insist I get out of the hotel and move into their hostel, where I can mix with internationals and speak in English. I don’t want that, I explain. I want to get the wrong end of the stick. I want the quiet and disquiet. I want to speak in black and white. I want to see things starkly. I want not to know.

I want to see Citadel Park, where a battle was fought at the end of a war. Once seized, Hitler designated the citadel a festung: a crucial fortification to be defended at all costs. Thousands perished fighting over it. I seek the park at dusk, find it at length and enter by a hundred steps, at the summit of which stands an overwhelming memorial, a testament to disaster, to a Europe at odds. I want to locate the headless people – a mindless sculpture that remembers those taken by war – but find only tanks, perhaps the very ones that blew off the heads. I clamber onto one of the tanks and enjoy sitting astride a lethal snout and watching my breath. I cross the park alone. Occasional couples on benches pause their conversations until I’m once more out of their lives. I fear the subject of their talk is of a serious nature. Why else would they come out here in dark winter to talk?

At the end of the day, I have not done enough. I do not know how to describe the architecture, the habits of the people, the colour of the eyes, the history of the city, the political situation. I have formed an impression but little more. Too much of Poland has gone over my head, when I might have reached up, intercepted it, pulled it down to my level. I’m supposed to be inquisitive. I have read some of Moran’s book and some Norman Davies and their grave erudition makes a fool of me.2 These chaps were serious gringos, serious fish out of water. Neither of that pair would miss the hotel breakfast. They would have it at 7.00 and then go to an early service at the Franciscan Church to get a look at the devoted, before strolling around town as the shops started to open. I have not seen either of the castles. I have not entered a museum or gallery. I have not taken a photograph. I have not seen the goats that are supposed to emerge each day at noon from the clock tower. I have asked few questions of people and the questions I have asked have tended to be vague and boring. Do you live here? What’s that? What time are the goats? Instead of seeing things and forming opinions and asking questions, I have drunk and smoked liberally. Such are my thoughts on this, my second Polish night, just before bed.

10 March. I’m woken by the sound of a crowd protesting in the square onto which my hotel room looks. I open the window, ready to remonstrate, to tell them to put a sock in it. An angry Pole is blasting something through a megaphone about the cost of lemons or the recent visit of David Cameron.3 I have missed the hotel breakfast. My nose is out of joint. I have a hangover. It is midday. Oh, wouldn’t they just be quiet! But then I remember that I have an interest in the welfare of all people, no matter their nationality or class or colour, and no matter the time of day or the extent of my headache. And so I put myself in the shower, experiment vainly with the vanity pack, then dress in the clothes of an ordinary person to go and inquire about the disquiet of ordinary people, and perhaps lend a hand.

The thousand-strong throng is arranged on Freedom Square, outside the neo-classical library. I approach a young couple to ask what all the fuss is about. Tessa tells me in perfect English that the protest has to do with the newish, right-wing, ultra-Catholic government, which has been ignoring the country’s constitution on a daily basis in an effort to destroy liberty and antagonise the EU and thwart a Russian invasion and bring back slavery and deport all non-Catholics and make it illegal not to have one’s forehead or forearm (whichever is more spacious) branded with the Polish eagle. Phew. I look forward to hearing the other side of the story, I say. There isn’t one, says Tessa.

I am introduced to Tessa’s father, who sounds like the headmaster of an English boarding school, and then her mother, who doesn’t. They are all going for pizza to discuss the general folly of the government. I am told to come along. I do as I’m told and I’m glad for the fact because before Tessa’s parents are halfway through their pizza, and despite the fact that I have barely said a word and am quite obviously hungover, I have been offered a teaching position at the school they run. It turns out they need someone to stand in a room of Polish eight year olds four times a week and say things in English. Can I manage that? Can I start on Monday?

‘But I’ve got no experience.’

‘Irrelevant.’

‘And I’m not very good with kids.’

‘Irrelevant.’

‘And I’m not very well behaved.’

‘Irrelevant.’

‘I don’t live anywhere.’

‘Irrelevant.’

‘I’ve not told anyone I’m here.’

‘Irrelevant.’

‘Would you employ an English-speaking goat?’

‘Almost certainly.’

I take the job.

1 Poland’s economy is not notoriously sluggish. If anything it is the opposite. It was the only European country to avoid recession after the 2008 financial crisis. A rule of thumb: if you like things reliable, only read the footnotes. The main text is a naive, real-time account, drawn from diaries I kept during my year in Poland. Of course the diaries have been edited, but I was careful to keep their tone and atmosphere, their misconceptions, their errors of judgement.

2 Norman Davies is a pre-eminent historian of Poland.

3 Cameron, then prime minister, visited Warsaw to ask the Polish prime minister if she minded if he made life a bit harder for the Poles living in the UK by cutting their benefits. This was part of a wider effort on his part to ‘get a new deal’ for the UK in Europe ahead of the forthcoming referendum. The idea was that a ‘new deal’ with the EU would make it harder for the public to vote to leave. In the event, the ‘new deal’ wasn’t up to snuff. ‘Cameron promised a loaf, begged for a crust, and came home with crumbs,’ wrote one columnist.

2

What’s the point having a home if it means nothing to you?

12 March. I walk to the address. It is below freezing. I don’t know the streets. Their names are reminders of my status – out of place, unknowing. Sienkiewicza. Słowackiego. Bukowska. I don’t know if the names refer to fish or trees or dead parliamentarians. I notice the registration plates. If the car was born before 2004, when Poland joined the European Union, the plate bears a little Polish flag. If it was born after, the flag is European. An incidental detail perhaps, but one that argues a redirection of the patriotic spirit. Polishness, at least superficially, and in this small way, has been made subordinate to Europeanness.

I don’t know how to pronounce the name of the young European I am on my way to see. Jędrzej. That’s how it’s written. What a queer set of letters. Surely the word is an expletive or imprecation, the noise Poles make when something goes wrong. A Pole drops a platter of dumplings – ‘Jędrzej!’ A Pole hears disappointing news on the radio – ‘Jędrzej!’

Jędrzej is a friend of my new employers. Like me, he is looking for a home. Having heard of my arrival he has invited me to look at a four-bedroom flat that has two rooms available. I don’t much like the idea of living with a civil engineer but am sufficiently open-minded to at least take a look. The flat is in a rough neighbourhood put up by the Germans in the late 1800s, when Poland was having time off from being a country. The district is Jeżyce. The street is Szamarzewskiego. Hardly rolls off the tongue. What’s the point having an address if you can’t articulate it? What’s the point having a home if it means nothing to you? I arrive at the building – 36 – give it a good look through the fog. It is elegant but tired. I know the feeling.

‘Hey there!’ says an American tourist tethering a bicycle.

‘Hey.’

‘I’m Yen-Jay. I’m a civil engineer.’

‘That’s nice. In fact, I’m supposed to be meeting a Polish civil engineer right now.’

‘Yup. That’ll be me.’

‘It can’t be. I’m meeting a Polish civil engineer who isn’t American and has a very, very different name to you.’

‘Let’s just go take a look, shall we?’

I take the room. It’s the smallest of the four. There are no curtains but plenty of motivational framed posters from IKEA. My favourite, probably owned by half of Europe, encourages the viewer to embrace their individuality.

Jędrzej is happy with his room, too. He has reason to be. It is three times the size of mine but the same price. When I point this out to him he looks delighted, not at all abashed that he’s on the right side of a massive injustice. I notice that Jędrzej smiles a lot. After signing a twelve-month contract, he goes to the kitchen window and smiles out of it for ten minutes. ‘Don’t ya just love the rain, Benny?’ It is hard to say if we are going to get along.

I sign a two-month contract with the option of an extension. I don’t want to commit to longer, not with Jenny about, or whatever his name is. The contract’s terms and conditions mean nothing to me. For all I know I can keep seven pets in my room, apart from at the weekend when I can have as many as I want. It hardly seems worth asking for a translation. Jenny is evidently quite good at English but it is mostly a sort of cartoon-English taken from the Disney Channel and I don’t think he’d cope with the legal terms.4 I pay the first month’s rent and another month’s worth for the deposit. I’m handed a set of keys. That’s all there is to it. The potentially troublesome bureaucratic procedure of finding a place to live has been dealt with. Compared to Paris and London, where it’s easier to get malaria than a roof over your head, securing accommodation in Poland has proved pleasingly simple.

In the evening I go to the local convenience store. I inspect the place as if it were a precious archive of exotic oddities. I am amused to find a pack of ground coffee beans called ‘Family’. The coffee’s packaging shows two adults and two children – the eponymous Family – sat around a table upon which stands a steaming percolator and four expectant cups. That’s fair enough, I think, depicting people looking happy in response to the commodity in question, but the children look no older than eight or nine. At what age do they start drinking coffee in Poland? The Poles in the UK have a reputation for being hard workers. Perhaps I have stumbled upon the explanation. Perhaps it’s because they start drinking coffee before they’ve hit puberty. Either way, I put a pack in my basket and continue shopping: the number of gherkins is astonishing; there’s no beef or chicken to speak of but about a kilometre of sausage all things considered; and milk comes in two qualities, 2.4 per cent and 3.2 per cent, which may, this being East Central Europe, refer to alcohol content.5

18 March. Tony and Marietta (my employers) met at a disco in Billericay, back in the 80s. Marietta had gone to England to find herself. Instead she found Tony. This must have been quite a shock. At any rate, and with no clear idea what she would do with him, when Marietta’s holiday in the Free World ended she returned to Poland with Tony on her arm. She hasn’t been back to England since, in case the same thing happens again.

The couple opened The Cream Tea School of English – which is also their house – in the mid-90s. It is a small, independent school that provides extra-curricular tuition to young Poles whose parents want their children to leave the country as soon as possible. The school is in the Starołęka district of the city, south of the centre on the east side of the River Warta. From my flat it takes two trams and a bus to get here, which is a bit of a pain. Also a pain is the idea of teaching. As Tony and Marietta introduce me at length to each of the trees and plants in their garden, and then their dog Pirate, I can’t help thinking that the time might be better spent telling me what (and how) they expect me to teach. In lieu of such instruction I am given tea and biscuits and told exactly how my tax contributions will be spent by the government. Some will go on infrastructure, a small bit will help Poland remain a member of NATO, while the lion’s share will help fund the 500-zloty monthly baby payments that are issued to parents to encourage breeding.6 ‘Now for the good news,’ says Tony, ‘your pension!’ Apparently, explains Tony, if I put in some decent hours over the next year I can expect to draw a pension of 10 zloty a week when I reach the age of 75 – enough to get a hotdog. There is little in the way of paperwork. All Tony requires of me is my British National Insurance number. It is frustratingly easy to enter the Polish tax system.

My first lesson is with D1. D, I quickly discover, stands for diabolical. The students, aged between eight and ten, are not in a cooperative mood. I have lost my patience before I’ve finished listing their names on the board.

‘You. What is your name?’

‘You just wrote it.’

‘Which one?’

‘Top one.’

‘How do you say that again?’

‘I’ve forgotten.’

‘At any rate, you are playing up.’

‘What does it mean?’

‘To play up is a phrasal verb. It means—’

‘What is a phrasal verb?’

‘You will learn about phrasal verbs when you start behaving yourself.’

‘So how are we supposed to understand you in the meanwhile?’

‘If you are able to heckle like that, I’m sure you’ll understand well enough.’

‘What is heckle?’

And so it begins. Sensing an alien out of his depth, a wanderer beyond the pale, the students are openly and joyfully defiant from the word go. It stands to reason. I can’t speak a word of Polish and they could speak Polish fluently when they were five. Ergo, I must be stupid. The people they have learned to respect and obey and defer to – parents, teachers, adults generally – know Polish to an advanced level, and are able and ready to manipulate their use of the Polish language, their tone and diction and syntax, in order to win arguments and appear awesome and earn authority. But the adult before them, supposedly a teacher, can barely say hello. He is either stupid or lazy, neither quality deserving of respect. This is the conclusion they all silently draw. When I step outside to hyperventilate, the ringleader, Lucas, briefs the others. ‘He is either stupid or lazy. In either case, he neither deserves nor shall receive our respect. Not until he pulls his socks up and finger out and gets up to speed. Agreed comrades?’ When I return to the classroom, Gosia and Basia are actively attempting to escape through a window, while another pair have begun to argue and tussle noisily, having failed to reach an agreement as to which of them is the greater nuisance. There is misbehaviour in front of my eyes and behind my back. When I ask for an example of the present continuous tense, Nella starts jumping on the table.

‘I am jumping!’ she shouts (which, to be fair, is an example of the present continuous tense). When Marietta pops in to check on my progress, D1 briefly settle and feign interest in what they did last weekend. Marietta is all smiles, is pleased with how it is all going, is proud of her gang of brats. Alone with me again, the feigning stops and the rebellion resumes. I try to be patient. I try to be philosophical. I even try to empathise. I tell myself that these kids have already spent the day at school, that no kid, not a single kid in the world, not the nerdiest, gawkiest, most scholarly child in the solar system wants to go to school after they’ve already been to school. When these kids get to Cream Tea they are ready to burst. If they are met with anything other than an iron fist – with me for example – they detonate. Their answers are nonchalant and sarcastic at best, hurtful and upsetting at worst. The kid who is normally easy-going becomes stubborn and obnoxious, while the kid who is normally a bit shy starts actively trying to sabotage the lesson. It is easy for all this to sound mirthful and harmless, to sound as if I’m playing it up, but I’m not. The lesson with D1 is actually stressful. I won’t name names, but Lucas is almost certainly related to the devil. Olivia, on the other hand, is devilish one moment and angelic the next, which is even more intimidating because there is no legislating for it. You can put Lucas in the cupboard and be done with it. But you can’t put Olivia in the cupboard and be done with it because she’ll turn into an angel in that cupboard and start to sob and bleat like a gorgeous cherub in the unfair dark. It would be like putting Joseph Stalin in solitary confinement only to discover upon his release 30 years later that it was actually Jesus. Besides, the cupboard wouldn’t even scare these kids. They’d sit down and play on their phones. They’d call their grandparents and explain how rewarding further education is. By the lesson’s end I am ready for retirement, ready for my pension, ready to book a vasectomy that I might assist the teaching fraternity by keeping class sizes down. I can’t possibly carry on. I must seek alternative work. I want to deliver pizzas. I want to deliver newspapers. I want to stack shelves. Now that I think of it, I bet most of the people stacking shelves in supermarkets are ex-teachers.

After a five-minute break spent in the garden trying to understand who I am and why I am here, I head upstairs to face M17, hoping M doesn’t stand for malignant and 17 for the size of the group. The students are aged between sixteen and eighteen. They are receiving extra tuition in preparation for their final high-school exams, the equivalent of British A-levels. Mercifully, the group are less inclined to get under the table, or on the table, or out the window, in part because the classroom is on the second floor. Unlike Lucas, M17 do not think it reasonable to take my journal and start reading it to the class in an affected English accent – ‘I was am-bi-va-lent about the dump-lings’ – and nor do they think it reasonable to make jokes about me in Polish, to the amusement of the rest of the class and to the detriment of the scholastic atmosphere and my self-esteem. As well as being altogether less demented, M17 are also more self-conscious, with the result that keeping a conversation going with them is a challenge. They care what I think of them. They care what their classmates think of them. In Freudian terms, D1 were light on superego, heavy on id. M17 have enough superego to sink a ship. When I ask what their motivation for studying English is they all insist they have none. I take that as my cue to wrap things up.

23 March. I spend my first wage packet in a pub called Dragon. I spend too much time here. It is proving an extension of the flat, a distant living room, a boozy en-suite. It has a homely quality and takes a varied crowd. A suit at the bar with a beer and newspaper. A pair of skateboarders sharing a pack of cigarettes in the courtyard garden. Students from Southern Europe talking quickly in mother tongues, asking when the weather will turn and where the wine is. Eighties pop music from the UK and the US plays as loud as the bartender wants, while conflicting music videos run on a TV above the bar next to a protruding dragon’s head. It’s a very social place – for me at least. I am sociable here because I am always alone and open and willing to practise Polish or English and so on. Moreover, I’ve been more or less in a good, gregarious mood ever since arriving in Poland (apart from when in a classroom), and such a mood can make anywhere social. I consider the corner shop a social place, and the trams, and even the public toilets. I spoke to my mum last night and she asked if Poland was a friendly place. I quickly answered that it was. But on reflection perhaps it isn’t, perhaps it’s me that’s friendly – buoyed by being away, apart, abroad – and perhaps it’s my friendliness that forces it out of others in a sort of unnatural way. All that is not to say the Polish are unfriendly – I’m sure some are and some aren’t just like everywhere else – but rather that I am probably not the best barometer. If you sent a deprived child into a toy shop and then asked them for a report, no doubt it would be glowing. Poland, for the time being, is a bit like that for me. I’m out of place here and it suits me.

I’m here for a date. I’m meeting Tala, who I connected with on Tinder.7 To be candid, I am less interested in Tala as a potential romantic partner and more as a pedagogue. This, I know, shouldn’t be my opening line. In the event, we have a good, solid lesson. I am introduced to Polish history (one thing after another by the sound of it) and then the Polish case system (distinct from the Indian caste system, which is a lot more fun believe me), which requires all nouns, even the most trivial, like carrot, to take fourteen different spellings, depending on what mood it’s in. When the subject drifts off learning Polish as a foreign language, Tala asks me what I think about the attacks in Belgium. I ask her what attacks in Belgium. She tells me that members of ISIS detonated themselves at various places across the country to make a point about something, but that the ‘something’ can’t be agreed upon. ‘No matter what,’ she says, ‘it will make it more likely that you leave Europe.’ I tell her I’m going nowhere, that I’m not scared. ‘Not you,’ she says, ‘the UK. In the referendum. Such events get distorted, are used to make people fearful. It happens here in Poland. Half the country is scared of Russia, the other half is scared of Muslims.’ I will almost certainly see Tala again, though next time I should offer to pay an hourly rate.8

4 Henceforth, and without his consent, Jędrzej became Jenny.

5 I regret this flippant comment about Poles being heavy consumers of alcohol. By suggesting that the Poles drink a lot I was lazily recycling one of those clichéd, often fallacious ideas about this or that group. The Irish eat potatoes. The English drink tea. That sort of thing. It is exactly this sort of clichéd thinking about the Polish – about Others – that I hoped to counter or complicate by moving to Poland. One reason for moving to a new place is to challenge one’s attitudes and intuitions, to destabilise one’s common sense. As evidenced above, old habits die hard.

6 The 500-zloty ‘baby payment’ is a divisive policy. It is essentially a child benefit. The government’s detractors insist that in the run up to the 2015 election the policy was dangled in front of the electorate like a reckless carrot. It is not inherently regrettable for a government to support families with more than one child, and yet if you were to ask any Pole who is against the governing Law and Justice Party for an example of its misbehaviour, they will most likely cite the 500-zloty baby payments. Why? Because they feel the benefit makes people reliant on the State when they should be reliant on themselves. And they don’t like the idea of people being paid to have sex.

7 Dating application millennials require to fill their weekday evenings. I used it a bit in England, and then a bit in Poland. It makes you a worse person in both countries.

8 I never saw her again.

3

Love is blind

24 March. I follow the blue-and-white scarves onto a green-and-yellow tram and then, about ten minutes later, off it and towards a stadium that looks expensive and rather like a giant metallic turtle. I buy a ticket and a scarf and place a bet that Poznań will win 3–1, which they haven’t done since 1655.9 The home fans, even before the match has commenced, are more vocal and tenacious than any set I have previously witnessed. It is a Tuesday night, an inconsequential league fixture, a mid-table clash and the stadium is barely a quarter full, and yet the noise! It is aggressive and militant, suggestive of an army going into battle. These supporters would make a good set of nationalists, a committed and indefatigable home army, buoyant and bellicose no matter the opponent, no matter the balance of power, no matter the odds and no matter the stakes. If it is a corner to them or a penalty to us (how quickly one sides), a tactical switch or the captain down with cramp, the noise alters not. In the context of a football match such fervour is, for the most part, harmless; but in a different context, a less sporting one, it could prove murderous. Flares are lit by the pocket of undaunted away support, answering those of the locals. Smoke fills the arena. The ball can no longer be seen, and nor can the players. All is one. It is an armistice of sorts, an impasse, a blank slate. The lack of clarity, that friend can’t be distinguished from foe, doesn’t bother me a jot, but you’d think it might bother the referee. Not at all. On they go invisibly, and still the crowd roars, not caring a bit that the match is no longer apparent. Love is blind. Perhaps it is less the match and more the idea of a match that gets them going, that keeps them going. A giant flag is unfolded and spread above the heads of 5,000. For those trapped below, the game is freshly obscured for a further fifteen minutes, but it matters not, for still they roar. There is a war on and that is all. The detail is beside the point. When Poznań score the fans celebrate by turning their backs to the action. The semiotics of it all, the encounter’s many meanings, are impossible to pin down. I am cold and almost alone in the west stand, quietly at odds with the raucous banks behind each goal. My bet does not come in. The battle ends in a draw, and the armies go home.

25 March. By now the flat is full. As well as Jenny there is Mariusz and Anna. Anna is a beautician. She carries out her work from home. Half of her bedroom is given over to equipment designed to increase people’s self-esteem by manipulating their appearance. The stream of customers is unrelenting. When I’m at the kitchen window smoking, looking over the dusty courtyard, I hear the shrieks of men having their armpits waxed. Besides a beautician, Anna is also something of a Matka Polka, a Polish Mother, which is to say she cooks sixteen meals a day, puts a lot of things in jars, and makes an effort to keep things clean. This last mostly involves making sure Jenny and I keep things clean. Mariusz doesn’t need to be told. He likes to clean. He likes to clean and is tall. That’s all I know. He doesn’t say much generally, and says even less to me, perhaps on account of the language barrier between us, which is higher than the one between Anna and I, which is about two metres high, and much higher than the one between Jenny and I, which is about half-a-metre high and much too low for my liking. Besides being tall and clean, Mariusz works as the manager of a café somewhere in the old town. He appears to work 140 hours a week. In his rare moments of liberty, Mariusz will put a pizza in the oven and vacuum the flat in his underpants. The jury is still out on Jenny. He’s an unorthodox character. Maybe paradoxical is a better word, or incongruous. I’ve seen him wash pots and pans in the shower, and now here he is washing socks in the kitchen sink. There is a severe, monastic quality to him – he likes to sleep on a bed of walnuts and will only eat steamed garlic and spinach – and yet he makes Mickey Mouse look like a manic depressive. He goes off to work each day, something to do with French windows, then comes home to gaze out the window and play the cello and generally goof around. I asked Anna the other day if Jenny is representative of the modern Polish man. ‘I hope not,’ she said. I don’t want to be unkind about Jenny. In part because he isn’t unkind. Jenny is always keen to share – his food, his opinions, his time – which is either good or bad depending on whether you want those things to be shared with you. He spends time with me at the kitchen window playing I spy in Polish – samochód, trzepak, drzwi, niebo. In many respects I think we’re on a similar wavelength. I know Anna thinks we’re on a similar wavelength, which is why she directs her domestic opprobrium at the two of us collectively, as though we were conjoined twins, were much of a muchness. Yeah, he’s not bad. I went into his room the other day and said, ‘Sorry to ask but have you got a pair of socks I could borrow?’

He stopped what he was doing, kind of smiled apologetically, then said, ‘I was just about to ask you the same thing.’ If great minds think alike, then like minds aren’t always great.

27 March. They embrace the coming of spring. The men are quickly in shorts, big milky calves unveiled to the sun. Girls, too eager perhaps, over-exhibit long-hidden forms. It is a long winter here, and it can be severe, so no wonder their haste. By donning little they remind themselves of their bodies, of their meaning and pull. Two handsome boys are currently wearing little outside the café on my street. One is waiting for Anita, the manageress, who I’ve been avoiding eye contact with for ten days now, for fear she’ll detect my fondness for her. I instantly and unfairly dislike the boy waiting for Anita. (It is unfair because one doesn’t dislike another person for having a likewise taste in books, but then there is more than one copy of the same book.) I eat a salad and drink an espresso and rehearse some phrases from my book, useful and everyday according to the cover, stuff like ‘Are guide dogs allowed here?’ and ‘Can sir tell me his birthday?’10 When Anita comes to clear my table, I am cold with her. I am cold because of the handsome boys, and in particular the one waiting for her to finish her shift so, I imagine, they can ride their bikes to a poetry pop-up together and do lines. Anita is undoubtedly prized, and by the look of it involved elsewhere, but sooner or later I’ll let her know of my fondness nonetheless, notwithstanding my fondness for the woman who drives the number 13 tram, and the girl who works at the shop at the end of the street. Am I behaving unfaithfully by idly admiring in several directions, for preferring to stay at the junction and dreamily ponder the ways? Men prize the thing ungained more than the thing itself, said Shakespeare, so maybe I’m best where I am, going nowhere, all things ungained.

4 April. I instruct D1 to write letters to hypothetical penfriends, outlining exactly what that penfriend can expect to happen during their forthcoming visit to Poland. Maciej, not given to hard work, lays down his pen and folds his arms. I give it a minute before satisfying him with attention. ‘What’s the matter, Maciej?’ He gives me a long look, and then his classmates a glance. He has something up his sleeve, that much is obvious. ‘Have you something up your sleeve, Maciej?’

‘I don’t want to write to my penfriend about what we are going to do.’

‘Oh? Why’s that?’

‘Because I don’t want to destroy the surprise.’

After this has gained a small applause, and after the hypothetical letters have been hypothetically sent, we play Monopoly. It is amusing watching them while I carry out the duties of banker, collecting fines and dealing properties. I try my best to keep some English chat going.

‘Julia. Will you build a café at Liverpool Street station?’

‘I think not.’

‘Why not?’

‘I do not like coffee.’

‘And Marcin, do you like living at Trafalgar Square?’

‘I like this house. It is a good shape.’

‘Life in jail must be difficult, Lucas?’

‘Takie życie.’ (C’est la vie.)

8 April. I had planned to go to the zoo but it started to rain so I go to the café on my street to drink green tea and pretend to read a book. When the moment is right I go to the counter to ask Anita for more hot water and whether she’d be willing to teach me Polish. (Nothing better to cower behind than a pretext.) She says yes to both, but in exactly the same way, so that I don’t know if Polish tuition is just another thing on the menu, asked for several times a day. I rip a page from my book (the page I was reading: twit), put my contact details on it, hand it to Anita as nonchalantly as possible, then leave before she can change her mind. The page is from A Country in the Moon. Walking back to the flat, I remember what was on it. On a balustrade in the gardens of Wilanow Palace, Warsaw, there are four statues symbolising the stages of love: Fear, Kiss, Quarrel, Indifference. I owe a debt to the afternoon’s rain.

9 Coincidentally, it was in 1655 that the Swedish Deluge began in Poland. The Deluge was brutal. The Swedes swept across the country butchering and burning and buggering indiscriminately. Poland lost half of its population. These days, Swedish presence in Poland is limited to a dozen IKEA outlets.

10 Honestly, that phrase book was a joke. If you’ve got a city-break in Poland coming up and you’re planning to hire a donkey or telegram your second-cousin, then I’d recommend it. Otherwise invest in something genuinely useful, like a wireless vacuum cleaner.

4

The city doesn’t shut up

10 April. Taking public transport unnecessarily is one way to see a place – its odd crumbs and loose ends, each vital to the whole, and no less alive for being less seen. I take the 10 tram from the Theatre Bridge and go south through Wilda. I watch a fridge-freezer being delivered to a language school, a range of protein powders being arranged in the window of Muscles Mental, and the Slavic chefs at Sultan Kebab getting lunch ready. At the end of the line there’s a crib in the bushes, and ‘I think I would like to die’ has been written on the body of a spare carriage. A cyclist trails us as we swing round and head north up Roosevelt Street and past the Hotel Vivaldi, where a man slams his hand on the tram’s window because he’s late by a whisker. We slip by an unorthodox church that looks like a chicken – a paltry part of God’s unreal estate – then conclude on the fringe of a housing estate. I get out and wait for the 4. A baby in pink points at me then looks to its mother for an explanation.

The 4 covers old ground – the queer church, Vivaldi, Roosevelt – then turns left on Saint Martin, passing a film-screening castle and a Danish fashion outlet, whose bare window suggests the Danes are wearing little this season. On Gwarna, Second Hand London is a towering outlet pushing jaded bottoms and washed-up brollies. A man with crutches gets awkwardly off at Greater Poland Square. He’s offered help but waves it away, preferring a tricky dismount. The 4 wants to head south, but I don’t, so I switch to the 6, which goes east past Porsche and Volvo dealerships towards Russia. On our right is Malta Lake, ordered by the Nazis and dug by their prisoners. I get off at the end of the line, where there happens to be a cemetery. As I wait for new wheels, a young woman joins me and then, using her self-effacing phone as a mirror, proceeds to remedy what she imagines is wrong. When the 6 finally shows, the girl is made-up.

I ride as far as Ostrów Tumski, the cathedral island, where I get off and walk to a new shopping centre. In the entrance hall, a public pianist plays to an audience of four, Pizza Hut is chock-a-block, and the window of a bookshop promises ‘bestsellery!’, which has me wondering if it specialises in books that are like bestsellers.11 The shopping centre’s slogan is announced in purple neon above the food court: #allaboutlifestyle, it says, which is just as well if you’re one of the developers and have skin in the game. The Dalai Lama said he likes to go to shopping centres to be reminded of all the crap he doesn’t want. I draw the attention of a peacekeeper when I start to photograph window dummies.

The 16 clatters back into town. We cut across a shopping street and then under the nose of the industrialist Hipolit Cegielski, whose workforce threw its dummy out of the pram in 1956, and so doing changed the course of history.12 Up past the Hotel Rzymski, where I leant from a window on my third morning in Poland and wondered at the fussy din below, not knowing, not believing that my future was down there, among the pent-up crowd on Freedom Square. Right onto Roosevelt and then quickly north, rising above the earth, gliding over cars on a brief tram highway. After an estate of towers in peach and pink, whose balconies bear pots and plants and bikes and washing, we finish at the university, or a part thereof. I get off and read. I read from the rough surface of the city’s endless text. I read the walls and panes and sheets and boards: a piece of new writing called The End will play for four nights at the cathedral; a fading promotion for sparkling teeth; an invitation to exercise. If you listen carefully, the city doesn’t shut up, and nor does the crowd of infants wearing hi-vis tunics (the better to be avoided) that is being led back to school by teachers across the street. Behind them, an old lady limps along at an inch an hour. I watch her put her shopping down and check her wristwatch in case she’s late and ought to hurry. I board the same 16, stand beside a pram and poke my tongue at the occupant, a boy of two or so, who ding-ding-dings the stop button in alarm. The mother tries to stop the boy’s music, but he’s evidently determined so she relents and lets him do as he wants. Nobody on the tram seems to mind the kid’s racket, which makes me smile. I sit behind two toddlers – Polish-African-American, says their mother. A young photographer, drawn to their relative difference, tries to snap the children on the sly but gets rumbled by the grandmother. The snapper explains his purpose in broken Polish. The mother doesn’t mind, but the grandmother is evidently less persuaded, for when the photographer gets on the floor for a better perspective, she fakes to kick him in the back of the head. When I start photographing the photographer that’s too much for her. She gets to her feet and gets in my face and nips my meta-instincts in the bud. ‘Photography is one thing,’ I imagine her saying, ‘but photography of photography is just smut.’ I move to the other end of the tram, where a boy’s jumper says ‘I’d Rather Be Mining’, and a girl’s T-shirt says ‘But I Mean Just Coffee’. Most of those being carried along read screens in lieu of daydreams, and I don’t blame them: the screens are quick and smooth and knowing, and besides, they’ve seen real life before.

11 It doesn’t. Bestsellery means bestsellers. As burgery means burgers, not something burger-like, as I first thought.

12 The protests of June 1956 in Poznań were conceived in the factory that Hipolit founded a hundred years earlier. The cost of living was punishing. The price of staple food items was put up another 10 per cent. A delegation of workers walked to what is now Plac Mickiewicza (then Stalin Square) to vent their spleen. Authorities reacted with undue force. Seventy or so of the demonstrators were killed. The seeds of a wider rebellion – that would finally lead to the Solidarity trade union and the fall of the Soviet Union – had been sown.

5

They wouldn’t leave if they didn’t have to

16 April.