Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

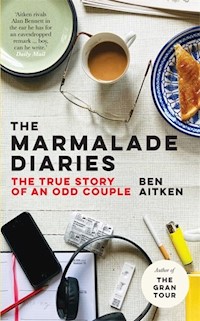

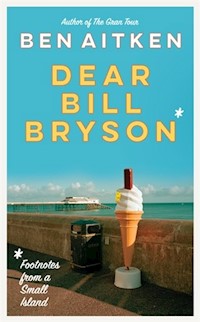

FROM THE AUTHOR OF THE ACCLAIMED THE GRAN TOUR AND THE MARMALADE DIARIES An irreverent homage to the '95 travel classic. 'It would be wrong to view this book as just a highly accomplished homage to a personal hero. Aitken's politics, as much as his humour, are firmly in the spotlight, and Dear Bill Bryson achieves more than its title (possibly even its author) intended.' Manchester Review In 2013, travel writer Ben Aitken decided to follow in the footsteps of his hero - literally - and started a journey around the UK, tracing the trip taken by Bill Bryson in his classic tribute to the British Isles, Notes from a Small Island. Staying at the same hotels, ordering the same food, and even spending the same amount of time in the bath, Aitken's homage - updated and with a new preface for 2022 - is filled with wit, insight and humour.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

For my grandparents.

vi

Contents

Preface to this edition

This wasn’t meant to be a book. I followed Bryson because I thought it might be a fun and modestly edifying way to spend two months. (How wrong I was.) But as the journey extended, so did my diary entries, and by the time I got to the finish line (i.e. Bill’s old house in Norfolk), the prospect of converting the diary entries into something approximating a book became, if not irresistible, then certainly less ridiculous.

When that conversion was complete, I was too bashful to send the first draft to any publishers or agents, so went down the independent route. I raised some money by getting ‘I Love Bill’ tattooed on my chest, and then unleased my awkward love letter into a world that mostly failed to notice.

I refer to the book as an irreverent homage because in essence that’s what it is. It’s an homage because it sprung from a place of affection and respect for Bryson and his work. It’s irreverent because I didn’t think 300 pages of unctuous flattery would do anyone much good. I wanted my journey to feel less like a pilgrimage, and more like an honest conversation with someone who wasn’t there.

I mention this (the book being an irreverent homage, rather than a pious and gushing one) to give the more zealous members of Bryson’s fan club a chance to back out now, and thereby avoid getting their knickers in a twist. Whereas Bryson is a demi-god of non-fiction, I’m just mucking about in the foothills of mediocrity – and that’s on a good day. Nor am I funny. If xI ever seem funny, or write things that seem funny, it is almost always by accident.

But enough pre-emptive apology and excuse. The book is what it is; and if it happens to bring a handful of readers some moments of distraction (from their prevailing worries, from their children, from the prospect of another national lockdown), then as far as I’m concerned its reissue has been justified. If it doesn’t, then it hasn’t, and I really ought to retrain as a traffic cone.

Needless to say, the Britain observed and recorded in the following pages is not the Britain that might be observed and recorded today. There is no pandemic, no Brexit, no electric scooters, and no old Etonian at the helm. (No, hang on. There is an old Etonian at the helm. Just a different one. Which goes to show how things have a curious knack of changing while staying the same.)

Countries – and all they contain and hint at and connote – aren’t the best sitters. They can’t, for the life of them, stay still. But the slipperiness of Britain shouldn’t deter any prospective portraitists, because a snapshot will always have value, and a sketch will always tell us something.

What follows is (at base and root and heart) just another set of notes from a small island, albeit a set of notes inspired by, and guided by, one of that island’s shiniest jewels – old Billy boy. (Who isn’t my biggest fan, by the way, not since I hurdled his back fence the better to deliver a letter.)

xi

Dear Bill Bryson,

Ever since I was a kid, I wanted to be a middle-aged American. I’d go about school wearing white socks and a fanny pack, mouthing off about taxes, telling anyone who would listen about my four-speed lawnmower. I used to tip the dinner ladies 25 per cent, for God’s sake.

Why? Well, in a word – you. I first saw you on television when I was about nine and should have been in bed. You were stood in some field, saying how nice it was. But it wasn’t what you were saying that impressed me – it was how you were saying it. I liked your voice, Bill. You sounded so understanding, as if you’d agree to any reasonable proposition – ‘Excuse me, Bill, but would you mind awfully if I threw an egg at you?’ ‘Well, I’m mowing the lawn right now, Ben, but how does three o’clock sound?’ I asked my mum if we could get you over for a few babysitting shifts. She told me to turn that rubbish off and get to bed.

To be honest, I forgot about you after that. Then I found your book one day, the one inspired by the field, the one you wrote twenty years ago before going back to the States, the one that was a bestseller in charity shops all over Europe.

Long story short, I’ve decided to retrace your steps. Why? Because I’m bored. Take it from me, there’s only so many tacos a guy can serve before he wants to put a pint of salsa down his windpipe.

First stop, Calais. You remember this town, Bill? You’ve little reason to, I suppose, since you did bugger all here. And the things you did do – well, I can’t even be sure you did those either. For example, you say you took a coffee on the Rue de Gaston Papin, but when I asked a local shopkeeper where I might find such a road, she answered with a look that suggested both xenophobia and pity, before telling me that such a road almost certainly xiidoesn’t exist, on account of Rue de Gaston Papin meaning Road of the Forgetful Squid, or something equally unlikely.

I’ve got to say, Bill, I was pretty wound-up. I slammed my copy of Notes from a Small Island against the counter and poked the shopkeeper in the eye. I mean, if you were fibbing about Gaston Papin, what else were you fibbing about? Does Milton Keynes even exist?

Disheartened, I asked a passing clergyman how to get back to the ferry terminal. He issued a volley of eloquent, and no doubt instructive, French words, which I pretended to understand perfectly, when, in fact, I understood nothing at all.

I reasoned that the ferry terminal must be near the water, and so headed for the beach, where I found a teenager chain-smoking electronic cigarettes and whispering philosophical maxims to a point in the middle distance. I pointed to the bundle of cranes and freight containers yonder and said, skilfully, and in French, ‘Boat?’ He shrugged six times and then quoted Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who once said, or so I’m led to believe, ‘In autumn there is hope’, which I understood to mean that he wasn’t at all sure.

I found the ferry without further ado and took up vigil on the viewing deck. The day was bidding adieu, and as the coconut cliffs of Dover began to rise from the Channel’s dark soup (overwritten?), I reasoned that things weren’t so bad after all – to be on these waves and under this sky and at the dawn of what promised to be an eventful, if unoriginal, journey around a small island. (What’s the deal with copyright, by the way?)

Yours,

Ben

1

Calais–Dover

There wasn’t really a young man quoting Rousseau; there was no passing clergyman; I did not poke a woman in the eye. I made those things up to get your attention, which is what you’re supposed to do at the start of a book. You’re also supposed to start with a description of the weather, so I should add that, for the most part, it was overcast in Calais.

I walked from the port into the centre along the Rue Constant Dupont and the Rue Pierre Mullard, street names that seemed elegant and thrilling, despite their essential banality. I passed a pub called Le Liverpool, which looked sad and unpopular. I suppose it was once busy with British day-trippers in shell suits stocking up on Kronenbourg and Côte du Rhône, the sort of people Bryson records seeing a lot of in ’94. I wondered about the provenance of this pub. Perhaps, in the late 80s, a canny Frenchman thought he’d cash in by giving the day-trippers a slice of home, understanding that the British tend to go overseas not to escape their culture but to find a warmer or cheaper version of it.

I came to the Place d’Armes, where I made a cursory effort to find a Virgin Mary bedside lamp. (Bryson bought one here, you see, before spending the evening playing with it in his hotel room.) I took a walk up to the old town to see the Rodin sculpture. The Burghers of Calais depicts half-a-dozen members of the city’s medieval middle class looking fed up, on account of the 2King of England having just announced that they were to be executed the following Tuesday. The burghers were eventually pardoned after the King’s better half intervened. Rodin has a lesser-known sculpture, elsewhere in Calais, of the men looking relieved.

I took the plat du jour at Au Bureau on the Rue Royal and drank two bottles of Stella Artois and it felt good and warm to be alone and softly drunk. I enjoyed the strange anonymity of being foreign, when one is at once more and less obvious to others, more and less significant. I knew no one in this city; I had no appointments or obligations; I had never cried or laughed or made mistakes here. For all anyone knew, I might have been arrogant or timid or generous or sad. As I reflected on the cleansing effect of travel – that I was once again at the beginning of my character – the beef stew arrived.

On the last ferry to Dover I went up to the viewing deck to enjoy the wind and the dark and to watch Calais recede. A Romanian asked me to take a photograph of him with the cliffs in the background. I told him it was too dark but he said it didn’t matter because the cliffs would still be there. He was excited to be returning to England (where he was a student) and told me, after just a few minutes’ conversation, that we are just little in this world and that it’s pointless to think too much. I told him about Socrates, who said that the unexamined life wasn’t worth living. ‘His life was worth examining,’ replied the Romanian, ‘yours isn’t.’

The Romanian was probably right, but up on that deck, 3passing through that channel, I couldn’t help but examine things. In particular, what the hell I was up to travelling again. Bryson had a good reason – he wanted a final glance at Britain before returning to America – but what was my excuse? Was I feeding an addiction? Was I putting off adulthood, with its manifold responsibilities?

Keen for an answer, I thought about Pascal, who held that the principal cause of man’s restlessness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his bedroom. It’s easy to read Pascal’s maxim as a celebration of doing nothing, but such a reading would be off the mark, I feel. Instead, is Pascal not simply pointing out that people are liable to wander and roam because they routinely fail to notice the pleasures and complexities inherent in those things with which they are most familiar?

One guy read Pascal’s celebration of going nowhere perhaps a little too literally. In 1790, Xavier de Maistre spent nine months travelling in his bedroom, rejoicing in the room’s hitherto unnoticed charms and associations: a busted mattress spring, for example, brought to mind a particularly robust old flame.

For me, then, Britain is a sort of bedroom. I was born and grew up in this bedroom. I think I know where the cupboard is and how the books are arranged. I know which corners gather most dust and I know which neighbour I can get a cup of sugar from. I know all these things but I know them complacently – lazily – for I stopped paying attention to my bedroom a while ago; it had become so familiar that it no longer seemed to deserve my regard. Was it not time, therefore, to take a look at those busted springs? 4

But why not take my own journey? Why copy Bryson? Was I not setting myself up for a fall by retracing the journey of a prize-winning supremo when my only writing credit to date was a spell subediting Family Fortunes?

Well, pragmatism certainly had something to do with it. First, copying is much easier than devising: not only would I not have to organise an itinerary, I wouldn’t even have to decide what to eat each night: if Bill consumed a frankfurter in Dover then I would as well. Second, when the time came to send a few chapters across to the Publishing Industry – to whom I am depressingly unconnected – would my imitation game not appeal to the Marketing Department? I could imagine snippets of the promotional junk: ‘Just like Bryson – if you really squint!’ And if I’m honest for a second, I suppose I felt that a younger, less cosy, more British perspective on this small island might not be the worst thing in the world.

When Bryson first visited Dover, back in 1973, he slept in a bus shelter with underpants on his head. He had tried to secure a bed at a guesthouse but was thwarted by the lateness of his arrival and the slightness of his budget.

A short walk from the ferry terminal took me to Marine Parade, where I found Bill’s shelter. I took out my copy of Notes from a Small Island and read about the sound of Dover’s waves and the turning beam of the lighthouse, and about a dog peeing on all upright things while its owner prophesied that the weather would turn out fine, in spite of all signs to the contrary. 5

Earlier that day, amid London’s anxious crowds – who were being herded here and there by unseen shepherds – I had felt lonely and sad. And yet, in a beautiful paradox, here I was, actually alone, in a bus shelter, in Dover, at midnight, on the cusp of two months mimicking a guy from Iowa, unquestionably happy.

I found a room at a nearby guesthouse, where I fell asleep to the sound of lorries rolling out of ferries, each carrying something, each going somewhere: pencils to Swindon, cabbage to the West Riding. I liked my bedroom.

In 1973, streaky bacon was one of the many things in Britain that Bryson had never heard of. Everything was strange and novel to Bill, and thus that much easier to warm to. He liked the way the British used cutlery and called each other ‘love’ and ‘mate’. He liked the way they got excited about tea. And even those things that displeased or confused him had an enchanting effect – all was improved by the gloss of novelty.

At breakfast the next morning, I wondered to what extent naivety is an asset to the traveller; whether my being a lifelong citizen of Britain would make me a worse chronicler of it. But in one sense I certainly was naive. For someone planning to write a book that sought to compare Britain now with Britain in 1994, I knew worryingly little about Britain in 1994. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given that I was eight in 1994, when my interest in current affairs amounted to a sometime concern about whether Keith from around the corner was coming out to play.

That said, I did know that Prince Charles gave up 6competitive polo in 1994 and that Great Britain, with typical restraint, won only two bronze medals at the Winter Olympics in Norway, and reasoned that, as points of comparison, these would serve as well as any.

Dover is a seaside town of 50,000 people who mostly pack salad or work for Brittany Ferries. With this useful information in mind, I left the guesthouse and walked along Townwall Street and then up to Dover Castle. At the entrance to the castle’s grounds I was asked for £20.

‘Can’t I just have a look?’

‘They all say that.’

‘And then what do you say?’

‘No.’

I cursed the woman’s sentience and yearned aloud for the mindlessness of machinery, which can be easily circumvented or tricked to think that artichokes are bananas. Even at this early stage of my trip I couldn’t afford to cough up twenty quid just to verify there was a castle up there. I had saved £1,500 for ten weeks’ travel. If I wanted to see such things as Dover Castle I would have to be flexible in my approach. Accordingly, at the rear of the castle’s grounds, I hurdled a 4-foot iron fence before making an awkward ascent up a bank matted with fallen leaves, at the top of which was a 30-foot medieval wall, which I hadn’t spotted on Google Maps.

Thwarted, I set off instead to see the famous white cliffs. After 30 minutes walking I encountered a pair of ramblers who told me to give up because it was another few miles and they 7weren’t that good anyway. One of the pair was evidently related to Socrates (the aforementioned chatty and thoughtful ancient Greek), because without invitation she commenced a lecture on local fracking, local xenophobia, local salad packing, and local battle re-enactment. At the end of the lecture she took me by the shoulders: ‘That’ll teach you to talk to strangers.’

It started raining, so I hastened back into town. Because Bill hadn’t given me much to do in Dover (an Italian meal, some quiet absorbing, a walk along Marine Parade), I lingered in a gift shop choosing a postcard, hoping the rain would abate. I bought one that depicted the quintessential features of Britain. If the postcard is to be believed, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be, life in Britain is mostly about cricket and seagulls.1

And then I took a photograph of Socrates. I hadn’t meant to, she just turned up in my viewfinder when I was attempting to frame a seagull playing cricket. She spotted me and enquired if I’d like to join her for another seminar and a cup of hemlock. I kind of stood there dumbstruck for a few seconds, by which time she’d pulled me into a sandwich shop and begun a new monologue about the difficulties faced by young people in the town. When she paused for breath, I turned to a bookseller at a neighbouring table and asked what he’d do with a spare afternoon in Dover. He said he’d probably start alphabetising the Science Fiction section.

Having no such section to alphabetise, I went to London.

1 Oh that it were!

2

London

I was first in London as a seventeen year old. My girlfriend at the time and I stopped there en route to an amusement park near Stoke-on-Trent. About a year later, when said girlfriend was studying medicine at Kings College in London and I was taking a forced gap year, having been rejected from all six of the universities I had applied to, I visited her and we went to see The Lion King at the Lyceum and ate at a cheap Italian restaurant on the Thames.

The following autumn I began a degree in literature and theatre at a university twenty miles outside of London. Accordingly, my friends and I would often catch a train into the capital to unburden ourselves of a decent chunk of that term’s student loan, and perhaps a little bit of bank credit, should the occasion call for it, which it invariably did.

After graduating I had little idea what to do with my new understanding of dramatic irony, so I copied everyone else and moved into London, taking a box room in Tooting and making ends meet by misguiding GCSE students as to how they might pass their forthcoming exams, and by helping out a guy with cerebral palsy, no doubt with equal ineptitude. (I remember on one occasion distractedly adding a teaspoon of mustard to his hot chocolate. My hourly rate was reduced by 16 per cent the following month, whence it remains.) In the evenings I would review plays, usually small productions out 9in the suburbs, and it was this toing and froing across London that did most to acquaint me with the city. A Korean adaptation of Macbeth in Shepherd’s Bush would be followed by a new play about particle physics in Kilburn, and that by a little-known Estonian comedy in Wandsworth, which I guiltily gave four stars, having fallen asleep during a monologue about Soviet beach resorts.

Anyway. That was then. Back to now. And back in particular to a pub near Victoria station called Balls Brothers, where I managed to vex the barman by ordering half a pint of lager and then having the temerity, upon being presented with a full one, to remind him that I had only ordered a half. He sighed in a way that suggested low job satisfaction, and I was reminded how easy it is to upset and be upset in old London town.

I took a table outside and tried to get chatting to my neighbour but the traffic – angry and abundant despite the congestion charge introduced in 2002 – was prohibitive. Big cities, I reflected, with their noise and combustion, make warm casual encounters difficult, a difficulty that over time hardens until it becomes a characteristic. City dwellers, both new and old, instinctively respect this characteristic and so it perpetuates.

Instead of talking to my neighbour, then, I watched people crossing the road urgently and unsafely, each stride desperate, each elbow sharp, each willing to take a hit from a Renault if they must, and raised a glass to lost patience, and lost civility, and to William Wordsworth, who suggested, when he wasn’t salivating over a daffodil, that city life pollutes the soul. 10

I had a reservation at Hazlitt’s, where Bryson had stayed twenty years earlier. The hotel has a lot going for it. It’s right in the middle of Soho, for a start, close to the house where Mozart and Hendrix lived (on separate occasions); Charles II, when he wasn’t taking sabbaticals in France, used to shampoo his horses here; and the hotel’s bedrooms are named after William Hazlitt’s ‘chums or women he shagged or something’, to quote Bill. I was told by the receptionist – who I found, after some minutes, under his counter mending a troublesome modem – to unpack my stuff in Mrs Millet, which isn’t something one is invited to do every day.

Hazlitt’s is also a pretty upmarket hotel, and you might be wondering what a guy like me, who can’t afford to take a look at Dover Castle, is doing booking a room at such a place. Well, truth is, for we might as well be straight about these things, I wasn’t paying for the room. I wrote to the hotel a few weeks before and explained my intention to copy Bryson’s journey and write a book about it, which I would then attempt to get published, suggesting that a renowned publisher had the tentative rights to the book, but declining to add that these rights were so tentative that the publisher wasn’t even aware of them. Mea culpa.

After dumping my things, I went and had a cup of tea at a café on Old Compton Street. The sun was blanching all things, robbing the scene of its moment in time – 22nd October 2013 – and lending, in its place, every conceivable decade – it might have been the 30s or the 60s or the 80s sitting on that terrace with that sun making everything pale and burnished and louder. All was silhouette: a rickshaw, a couple holding hands, 11the tall erect postures of terraced buildings. In such a light the street became a poem, reduced to its essential lines and truths, and I wanted to commit the poem to memory but knew that a syllable or two – nay, whole stanzas – would get lost, and I knew that taking a picture was pointless for no camera could capture what I wanted captured because it was coloured by my mood. Instead, I watched the passing profiles: an Orthodox Jew with red headphones, a beautiful Arab man, a punk, a pensioner, and a woman marching back and forth in summer colours like an uncertain peacock. The diversity pleased me because it promised a wider range of potential experience: who we might kiss, how we might dress, who we might be!

At Leicester Square I looked for a long time at a sous-chef working in the kitchen of a Café Rouge restaurant. Restaurants like to expose their kitchens these days, perhaps to assure punters the chef isn’t blowing his nose on slices of cured ham. As the sous-chef salted a pan of mussels, I wondered what allows certain scenes to gain and hold our attention as we pass through a city. There were perhaps a thousand things I might have been drawn to that afternoon – a statue of Shakespeare, a line of buildings on Regent Street, a collision of motorcycles outside the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square. What was it about the sous-chef at work in the kitchen of a French chain restaurant that arrested me? Perhaps, having done such work, sympathy drew me toward the kitchen’s toil. Perhaps nostalgia had me wanting to return to the fray, to re-enlist, to once more turn meat and slice leek and ladle soup into bowls. Or perhaps it was the sous-chef’s peculiar beauty (his nose was somehow rectangular) that attracted me, or the aesthetic 12puzzle produced by the half-clean windows, the griddle steam, the too-large clock posing silently behind it all.

At Covent Garden I joined a tour group doing a sweep of key sites. Cutting through Trafalgar Square, our guide spoke of Henry VIII and Horatio Nelson and a man called Michael Fagin who, in 1982, managed to break into Buckingham Palace and ask the Queen for a cigarette. At St James’s Palace, we paused to watch the preamble to the christening of a boy called George. Our guide asked whether there were any republicans among the group; whether there were people who considered the monarchy a significant waste of dosh, who thought all the pomp and ceremony and primogeniture made a mockery of claims that Britain had made steady intellectual and social progress since Henry VIII was at the helm beheading women for minor infringements. A French girl and I raised uncertain hands.

Outside the House of Commons we learnt that Guy Fawkes was a Catholic and that the wally wrote a letter warning of the forthcoming explosion of Parliament to the only Catholic MP, who duly showed the King. Fawkes was caught in the cellars of Westminster Palace sat on nineteen barrels of gunpowder reading a magazine. He was asked what he was doing sitting on nineteen barrels of gunpowder and he said he was reading a magazine. For being a sarcastic so-and-so he was cut into sections then set ablaze.

On my way back to the hotel I passed through Angel Court, along whose length I counted and photographed thirteen warnings or cautions or dictates, to do with smoking or loitering or littering or playing ball games or parking your bike or letting 13your dog relieve itself. It’s easy to think that the measures taken to suppress crime – and the infringement on individual liberty involved therein – were always more severe in earlier epochs – when Fawkes was set ablaze, for example – but the 30 metres of Angel Court, with its plenitude of threats, suggest we are more policed than ever.

One of the things that Bryson most liked about London were the polite blue notices mounted to certain buildings that explain that Charlie Chaplin once took a bath on this site and so on. He considers such notices – along with cheery red pillar boxes and benches and pedestrian crossings that actually work – ‘incidental civilities’ that, when experienced together, do a lot to recommend London as a place of calm and steady decency. I do hope that such things don’t fall too much out of fashion, that such politeness isn’t replaced to too great an extent with the cautionary warnings that characterise Angel Court, for it would be a shame if anxiety got the better of civility, in London or any place.

Bryson wrote that Hazlitt’s was enjoyably unlike a hotel; that if one phoned down for a bar of soap, for example, one would invariably receive a pot plant. That evening – there being nothing erotic or thrilling on television – I phoned down for some soap.

‘Reception.’

‘It’s Aitken.’

‘Who?’

‘Look, can you send up a bar of soap?’ 14

‘Is there not one—’

‘There was, yes. But I’ve used it already.’

‘There should be extra soap under the sink.’

‘Yeah, I’ve used that as well.’

‘What have you been—Is everything … okay?’

‘Sure, things are fine, I just need more soap.’

A few minutes later a nice young woman from Wolverhampton delivered some soap. Now if that isn’t progress, I don’t know what is.

3

London 2

I felt obliged, the following morning, to have a good wash, given all the fuss I’d made about soap. After checking out, I went in search of the old Times building on the Gray’s Inn Road, where Bill was a subeditor back in the 80s. Passing through Bloomsbury and cutting across Bedford Square and Southampton Row and Kingsway, I thought a little about Bryson’s stated inability ‘to understand how Londoners fail to see that they live in the most wonderful city in the world’. One of the reasons Londoners may fail to see their good luck, Bill, is because the existential taxes levied upon them are blinding. The cost of living, the working hours, the commutes, the competition for jobs and resources – such things are depleting, are enervating, so that when one does have disposable time in London it’s not uncommon to be too spent to do anything purposeful with it. Dr Johnson reckoned that London had ‘all that life can afford’, and he may well have been right. But I’m inclined to think that London affords too much of each thing – 250 theatres, 11,000 discos, 93 postmodern exhibitions – so that one is burdened and perplexed by choice, and finally does nothing with their Sunday save for drink tea and watch bad television, just like everyone else in the country. In a sense, then, Londoners – the ones I knock about with anyway – live relatively impoverished lives, in spite of the many wonderful things that, on paper, are afforded them. Hey-ho. 16

After failing to find the old Times building on the Gray’s Inn Road, I went to Wapping, taking the tube from Chancery Lane to Tower Hill. Bryson, it would appear, has a soft spot for London’s underground network. He enjoys the feeling of being so far down; the smells and the orderliness; the genius of Henry Beck’s map, which understood that sequence was more important than scale. Bryson enjoys imagining from below a semi-mythical London above, where Holland Park is full of windmills and Swiss Cottage is a gingerbread dwelling. I sometimes play this game with my friend Anthony (the lad who reduced my wage by 16 per cent). Our version of the game is perhaps a little more down to earth. We don’t imagine windmills or gingerbread buildings – cute, beckoning things. Instead, we imagine Baker Street to be full of unemployed butchers, and Tooting Bec a mess of honking cars.

On this morning my tube carriage was full of school kids heading east to Leyton. I spoke with their teacher, who told me about their visit to the Victoria and Albert Museum in Kensington, during which one of the kids had got in trouble for wiping snot on ‘Samson Slaying a Philistine’ by Giambologna. For some of the kids this was the first time they had been into central London. Their London was elsewhere, he said, where there were no museums or tourists or meetings of Parliament. In their place are fast-food takeaways and pawnbrokers and bookmakers and launderettes and language schools and old-fashioned street markets that do not offer nineteen types of olive. I thought about London’s celebrated diversity and asked: How multicultural and meritocratic and liberal can a place 17purport to be when it is patterned with such firm demarcations, perceived or otherwise?

The Times – and with it Bryson – moved from the Gray’s Inn Road to a new site in Wapping in the early 80s. The idea, as far as I understand, was to bring together News International’s British interests, to reduce costs, and to implement new printing technology. This last, alongside general cost cutting, would occasion, in 1986, the dismissal of 5,000 staff. Of course things kicked-off, with the dismissed staff and their affiliated trade unions on one side, and everything and everybody representing News International on the other. The conflict, Bryson reports, developed into ‘the most bitter and violent industrial dispute yet seen on the streets of London’, and saw those that avoided the chop being escorted off the Wapping site after work each day in police convoys. Bryson remembers one unfortunate journalist who had a beer glass smashed in his face by an ex-colleague from Tunbridge Wells who had lost his wine column. The guy nearly died, ‘or at the very least failed to enjoy the rest of his evening’.

Bryson also recalls the efforts made by News International to keep up staff morale during the hoo-hah. Each employee received a morale-boosting ration that consisted of a ham sandwich and a warm can of Heineken, a parsimony that almost led, in turn, to further industrial dispute, as members of the Foreign Desk or wherever began drafting placards encouraging management to ‘At Least Chill The Flipping Beer’, or to ‘Put Some Effing Mustard In The Sandwiches’.

Bryson makes his own joke at his former employer’s generosity (or lack thereof), imagining a letter sent to his wife in the 18wake of his death defending the cause of News International. ‘Dear Mrs Bryson: In appreciation of your husband’s recent tragic death at the hands of a terrifying mob, we would like you to have this sandwich and can of lager. PS – Could you please return his parking pass?’

Bryson returned to Wapping to call on a former colleague, with whom he had arranged to have lunch and compare bald spots. The Wapping site is now redundant and ready for redevelopment as flats, and so if I were to compare bald spots with anyone I would have to go across the street to the shiny new offices, which sit on the fourth floor of Freedom Tower Seven or whatever it’s called, part of a plate-glass jungle overbearing a pleasant marina.

Entering the reception area of Freedom Tower Seven, I genuinely had no idea who I would ask to speak to, or indeed what I would say if introduced to someone. (‘Er, sorry to bother you Christopher on glossy double spreads, but might I ask how big yours is?’) The receptionist asked if I had an appointment. I hadn’t. She asked what the nature of my enquiry was. I said it was to do with a trip I was taking that might be of interest. She passed me the receiver and said she was putting me through to the travel editor. I told her quietly that that was a ridiculous thing to do but the receiver was already making a noise.

‘Bleach.’

‘Sorry?’

‘This is Bleach. What is it?’

‘I want to pitch a story.’

‘Must say this is pretty old school just rocking up.’

‘Thank you.’ 19

‘So what have you got?’

‘Bryson’s Notes From a Small Island.’

‘What about it?’

‘Twentieth anniversary of publication.’

‘So what?’

‘I’m retracing the journey.’

‘Has that been done before?’

‘No.’ I think. ‘Same hotels, same sandwiches, same brothels, etc.’

‘Don’t remember any brothels.’

‘You must have the abridged version.’

‘Anyway.’

‘Anyway. I started in Calais on Monday. Then Dover. Then London. He came to Wapping to compare bald spots with old colleagues. How big is—’

‘Look, this is a nice idea, but aren’t you setting yourself up for a fall by competing with a legendarily funny writer?’

‘Almost certainly.’

‘Send me something when you’re done. I promise to look at it.’

Four months later, at my journey’s end, I sent that something and, as promised, he looked at it. He didn’t publish it, but I like to think that he gave it a good long look.

After lunching in the canteen with his pal (who had a smaller one apparently), Bryson takes a walk through the streets of Wapping. Considering the many rows of former wharves and warehouses – now so many apartment buildings – he quivers 20at the thought of ‘these once-proud workplaces filled with braying twits named Selena and Jasper’. In 1960, he tells us, 100,000 people worked on these docks. Yet within twenty years, the tides of commerce and industry now calling for cosmetics and financial derivatives, that figure had declined to exactly none at all. The river, once busy conveying condiments and spices, was now as ‘tranquil and undisturbed as a Constable landscape’.

I left that landscape and headed for Waterloo station. Doing so, I entered a fruit-and-veg store and was charged 52p for a banana.

‘52p? What comes with it?’

‘A receipt.’

‘That’s the most valuable banana in London.’

‘Then aren’t you lucky.’

‘I daren’t eat the thing.’

‘Suit yourself.’

‘A banana was 7p in 1994.’

‘Things change, my friend.’

I came to Waterloo Bridge. As I crossed, it all felt too much. The Shard was there getting longer, and St Paul’s was there getting older, and the Shell Building was there getting richer, and the National Theatre was there and so was the London Eye – each bearing over me, each calling my attention, each with their unique stories, dimensions, agendas, materials, residents and employees. About me, it felt, was an impossible encyclopaedia of endeavour, of going on; an impossible meaningful weight that deserved decoding, that deserved to be borne. But it was all too much. I’d had enough story for one day, enough 21London, enough tube and street, enough seen and heard and considered – just enough, thank you. A man played the clarinet, his cloth cap put out for coins. I hadn’t the energy to go to my pocket. I closed my eyes and sighed. I walked on.

4

Windsor

The last time I was in Windsor I spent a good portion of the evening in a shopping trolley. When I was studying a few miles away in Egham, a group of us would come into Windsor now and again to make an assessment of the Norman castle, or to feed the swans on the Thames, or to cross the bridge into Eton to ogle the illustrious, or, having exhausted such lowbrow pursuits, to ride down the cobbled slope of Peascod Street on four wheels. At the bottom of Peascod Street, the trolley would usually be steered eastward by a geography undergraduate onto William Street, where there was – and remains – a nightclub called Liquid. We would toss the bouncer a set of keys and tell him to go park the trolley, before heading into the brain-shrinking fuzz of the disco, where we would do what we did best, which was to meditate at great length on the pros and cons of this or that chat up line, without ever dreaming of putting any one of them to use.

The Castle Hotel had kindly agreed to put me up. When Bryson stayed at the hotel he must have been given a room at the far end of the modern extension, for he suggests that its position was ‘handy for Reading if I decided to exit through the window’. My room, on the other hand, was centrally located, and far bigger and nicer than anything I deserved. In celebration, I took off my clothes and put on the big television and ran the big bath and opened the big bottle of sparkling water, 23thinking to add it to the bathtub, because the more bubbles the better, right?

That done, I experimented with the basket of lotions and gadgets which perched mysteriously and invitingly on the cistern, rubbing this here and exfoliating that there, while retaining the good sense, amid this orgasm of self-improvement, to pop the complimentary shower cap in my backpack, in case, as was forecast, it rained the next day. When, some hours later, I stepped out into Windsor’s regal air to see what the town did with itself on a Thursday evening, strike me down if I didn’t look like Brigitte Bardot.

I met an uptight Spaniard in the Duchess of Cambridge, had a bowl of soup somewhere else, and then wandered over to the old train station, now a pleasant-enough collection of luxury soap shops and chain restaurants, where I had three pints of lager in a Slug and Lettuce. Returning up Peascod Street toward the hotel, I knew full well that I couldn’t possibly carry on my evening at Liquid nightclub, not on my own, not on a Thursday, and not when I’d already had enough to drink and needed to be up in the morning to take advantage of the cooked breakfast and walk five miles to Virginia Water with a shower cap on. No, that would be reckless and inappropriate and suggestive of a weak personality. Besides, the place would be full of students and pleasure-starved locals trying to forget that they work in recruitment or the PR department at Legoland. And I wouldn’t know any of the songs, or any of the fashionable dance moves, or what drinks were on promotion. My having lived for 27 years was probably in contravention of the dress code. No, I couldn’t go to Liquid. 24

I tossed the bouncer my keys and asked him to go park my trolley. Climbing the stairs to the main disco, I was delighted with my decision. Within minutes of entering said main disco, I wasn’t. There were 50 or so people affecting to dance, each in skinny jeans or skinny skirt, each made otherworldly by cream and wax and spray, each moving like a difficult worm, the boys on one side of the room, like the Montagues, deep in shallow shouted conversation as to how best to approach this or that difficult worm in the skinny skirt. What is it that stops them asking, that stops us all asking, I like you do you like me too?

I go to the V.I.P. area and explain to the guy whose job it is to decide who is and isn’t very important that I am looking for somewhere quieter where I can perhaps read a chapter of my book. Try Slough, he says. With a bit of encouragement he admits me to a garish lounge where the drinks are 40p more expensive. But there is no music, and so I read. I read about Bryson holding up Princess Diana in Windsor Great Park and as I begin to slide into the warm cuddle of his prose, I am approached by a teenage version of Hugh Grant.

‘I like your niche,’ says Hugh.

‘Huh?’

‘You’re not actually reading that book.’

‘No?’

‘It’s an angle. You’ve read The Game by Neil Strauss, right?’

‘No.’

‘You’re lying. What you’re doing is explained in chapter seven. You’re at once making yourself available and unavailable while appearing clever. Where’d you get the book, anyway? 25Was it just lying around?’ He inspects it. ‘Mistake. If you’re reading about travel, makes you seem non-committal. Drink?’

It’s kind of unnerving eating breakfast alone in a hotel. For one, there are so many things on the table, most of which are tricky to identify, especially when you’ve nobody to consult with. I’m pretty sure some of the gear from the bathroom – the little pots of cream and lotion – are put out with the breakfast things, to give the impression of abundance and luxury. Another thing is that the other guests are always so fascinated by you. They’re so bored of each other that all of a sudden you’re the most intriguing thing in the world. Is his girlfriend still in bed? they whisper. He can’t be here on business? He’s not actually reading that book – it’s a niche. Look, Ted, he’s dunking his sausage in moisturiser.