Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

In Cambridge in the 1950s, several research groups funded by the Medical Research Council were producing exciting results. In the Biochemistry Department, Sanger determined the amino acid sequence of insulin, and was awarded a Nobel Prize for this in 1958. At the Cavendish Laboratory, in the MRC Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems, Watson and Crick solved the structure of DNA, and Perutz and Kendrew produced the first three-dimensional maps of protein structures – haemoglobin and myoglobin – for which all four were later awarded Nobel Prizes. This made it timely to create, in 1962, a new Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge by amalgamating these groups with other MRC-funded groups from London. The Laboratory has become one of the most successful in its field, and the number of Nobel Prizes awarded over the years to scientists at LMB has risen to thirteen. This book follows the development of LMB, through the people who moved into the new Laboratory and their research. It describes events and personalities that have given the Laboratory a friendly, family atmosphere, while continuing to be scientifically productive.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 663

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

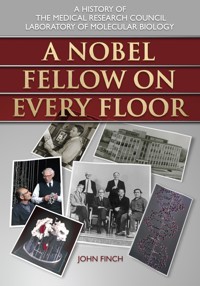

A Nobel Fellow on Every Floor

A History of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology

John Finch

Contents

Origin of the Book

When I started my ten years as Director at LMB, following on from Max Perutz, Sydney Brenner and Aaron Klug, I felt that the wonderful history of LMB, stretching back for 50 years or more, was beginning to fade from memory. The younger students and postdocs, who were naturally focused on the latest discoveries, knew little about the revolutionary achievements made by the founders of the Laboratory.

We started a small archive and history group and looked for someone to write a book about the origin and evolution of the Laboratory, and soon discovered that Soraya de Chadarevian, a member of the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge, had already been working on a book, supported by a Wellcome Trust grant. Her topic was broader than we planned, covering the history of molecular biology in the UK. Her scholarly monograph, Designs for Life: Molecular Biology after World War II, was published in 2002 and has met with wide acclaim.

Soraya suggested that there might be another book to be written, providing more of an informal family history of the Laboratory including events and photographs of sentimental as well as historical interest.

As it happened, John Finch had just reached the normal retirement age, having joined the Laboratory when it opened on the Addenbrooke’s site, so he was well acquainted with many of the people and events. After some thought, John agreed that this would be a great project, but I’m sure he did not imagine that it might take ten years to complete. It has been a massive undertaking. Annette Faux, our now full-time LMB archivist, has recently joined John in his project. Annette came to the Laboratory in 2001 and has worked on the assimilation and annotation of all the photographs.

This book captures and illuminates the excitement of the inception and development of molecular biology, to which LMB has made many key contributions. I am sure it will appeal to the many members of the Laboratory, present and past, who want to find out about or be reminded of earlier events and personalities. It will also appeal to people who seek an informal account of a remarkable period of scientific history.

Richard Henderson

25 April 2007

Author’s Introduction

I retired officially in 1995 and, as well as finishing up the odd bits of science I was involved with, spent my first year of retirement organising a meeting in honour of Aaron Klug, marking his 70th birthday and the end of his ten years as Director of LMB. After a few months in Japan, in Masashi Suzuki’s laboratory, I returned to LMB with an invitation to collaborate with Wes Sundquist, on the structure of tubes of the core protein of HIV that he was making in Utah. Richard Henderson, who was now the LMB Director, then asked if I would like to write a history of the laboratory. Since I had been in LMB since its beginning, and was now retired and had time for such things (and there was no one else), I seemed a good candidate for doing this, ‘with the knowledge and perspective of an insider’. After some deliberation, I agreed, although it began very slowly for the first year or two, with most of my time being spent working on the HIV tubes and other things.

Richard’s initial idea was that my book would follow what happened to the people and groups who made up the intake into the LMB when it was opened in 1962. The idea of following people rather than the strict science suggested more of a ‘family history’ of the laboratory than the academic history of molecular biology that was being written by Soraya in her Designs for Life. However, it seemed natural to put the family into context with its history, pre-LMB, and with other groups and people that have joined LMB later. But as about 3,000 scientists have worked at LMB since 1962, this has been rather selective and biased by my own knowledge (and lack of it).

The pre-LMB history is described in the first five chapters. The first two tell how Max Perutz came to work at the Cavendish in 1938, of the creation of the MRC Unit there in 1947 and of the first protein structures in 1958 and 1960. The third chapter tells of Watson and Crick and the DNA structure, and the fourth, of Crick’s transition with Sydney Brenner towards molecular genetics. The fifth chapter describes the events leading up to the creation of the new LMB.

Chapters 6–8 record what happened to the groups after their installation in the three Divisions in the new laboratory. Chapter 6, dealing with the Structural Studies Division, is considerably larger than the others. This is partly because that Division has been numerically greater than the others, and partly because of the many different topics studied by Aaron Klug, but no doubt helped by my being a member of that Division myself. The various back-up sections, such as the workshops and library and some laboratory institutions, are described in Chapter 9, and other history and memories of LMB alumni are collected in Chapter 10.

The time span is rather variable – of the initial laboratory occupants, John Kendrew more-or-less ceased his research work on coming to LMB, although he continued on the organisational and administration sides until he left in 1975. Aaron Klug, at the other extreme still (in 2006) has a small research group. I have not included the Neurobiology Division which was set up in 1993, much later than the others, but its eldest LMB inhabitants, Nigel Unwin and Michel Goedert, are dealt with in their previous incarnations in Structural Studies and the Director’s Section.

As with any family history and its photographic records, the most interested will be the family itself, and I hope the book will be a pleasant and useful reminder of life in LMB. Following the laboratory tradition, I have kept to first names as far as possible, although in some places surnames are used where they feel more suitable.

I have gathered much information from the laboratory archive collection of audio-and video-tapes of interviews with and talks by staff and ex-staff. Much of what I have written has been gathered from, and vetted and added to, by the people concerned. Various history books and articles have been consulted, as indicated in the text.

Most of the photographs are from the collection of our Visual Aids section, although quite a few of the earlier ones come from the Cold Spring Harbor Symposia and from people who were sufficiently farseeing to take them at the time and keep them.

Thanks to Sid Altman, Brad Amos, Uli Arndt, Joyce Baldwin, Bart Barrell, David Blow, Mark Bretscher, Dan Brown, George Brownlee, Jo Butler, Alan Coulson, Valerie Coulson, Bob Diamond, Wasi Faruqi, Mick Fordham, Michael Fuller, John Gurdon, Dave Hart, Brian Hartley, Ken Harvey, Richard Henderson, Jonathan Hodgkin, Terry Horsnell, Ross Jakes, Rob Kay, John Kendrick-Jones, John Kilmartin, Aaron Klug, Annette Lenton, Brian Matthews, Andrew McLachlan, Angela Mott, Hilary Muirhead, Michael Neuberger, David Neuhaus, Brian Pope, Terry Rabbitts, Michael Rossmann, David Secher, Jude Smith (now Jude Short), Wes Sundquist, Nichol Thomson, Andrew Travers, Alan Weeds, Tony Woollard and everyone else who read through sections of the manuscript or provided material for inclusion and also those who allowed the reproduction of their memories of LMB and letters in the Appendices in chapter 10. Thanks also to Hugh Huxley, Soraya de Chadarevian, Richard Henderson, Tony Crowther, Mark Bretscher, Peter Lawrence, Cristina Rada and David Secher for reading through, correcting and commenting on large chunks of the text. Thanks too to Neil Grant who spent much time getting many of the photographs used in a form suitable for publication.

Thanks also to Robin Offord for providing me with the title; ‘there’s a Nobel Fellow on every floor’ was a line in the song he wrote and sang at the celebrations for the four Nobel Prizes awarded to Max Perutz, John Kendrew, Francis Crick and Jim Watson in 1962.

I would like especially to thank Annette Faux, who had the mammoth tasks of locating and sorting out all the photographs included in this book and finding out the answers to queries that cropped up during the writing process.

John Finch

May 2007

CHAPTER ONE

How molecular biology came to the Cavendish

With its strong reputation for basic physics under Rutherford in the 1930s, the Cavendish Laboratory may seem an incongruous spawning ground for molecular biology. It came about because Cambridge was the birthplace of the use of X-ray diffraction for structure determination: W.L. (later Sir Lawrence) Bragg initiated its use for his work on salts and minerals, and J.D. Bernal began its application to protein crystals, and attracted Max Perutz and John Kendrew.

LAWRENCE BRAGG

W.L. Bragg was born in 1890 and educated in Adelaide, where his father, W.H. Bragg, was the Physics Professor (and his grandmother the Alice of Alice Springs). The family came to England in 1909 when his father was appointed to the Physics chair at Leeds, and Bragg began as an undergraduate at Cambridge.

He had just graduated in 1912 when the first X-ray diffraction photographs from a crystal (of zinc blende, ZnS) were reported from Friedrich and Knipping in Munich. The main aim of the experiment was to demonstrate the wave nature of X-rays, and their paper was accompanied by one from Max von Laue attempting to interpret the results in terms of the crystal structure. However, the structure was more complicated than von Laue assumed and there was also confusion on the mechanism of diffraction, so that even the proponents of wave X-rays did not find the explanation convincing.

Bragg’s father had been interested in X-rays since their discovery in 1895 and because he believed they were particles, Bragg was initially also biased towards this view and suggested that the X-ray patterns were produced by particles being channelled down avenues between atoms. But on thinking of the treatment of light diffraction by a diffraction grating, he realised that the X-ray pattern could be explained by the selective reflection of specific wavelengths from a continuous spectrum of wave X-rays, from planes of atoms in the crystal according to the same equation nλ=2dsinθ. This did not explain the ZnS pattern if a simple cubic lattice were assumed, but did so completely if the cubic lattice were face-centred. Thus Bragg confirmed that the phenomenon was diffraction, that X-rays were of a wave character, and also that they could be used to determine crystal structures. These results were presented at a meeting of the Cambridge Philosophical Society in November 1912, reported in Nature in December, and in more detail in a 1913 paper.

1. Lawrence Bragg, c. 1915. Courtesy of AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Weber Collection

Bragg was keen to pursue the diffraction work and W.J. Pope, the Professor of Chemistry in Cambridge, who was interested in the theories of crystal lattices, suggested he work on NaCl, KCl, KBr and KI and obtained large crystals for him. The X-ray photographs obtained by Bragg were simpler than those from zinc blende and led to a complete solution of their structure. However, the conditions for experimental work at the Cavendish were not very satisfactory as Bragg later described:

When I achieved the first X-ray reflections, I worked the Rumkorff coil too hard in my excitement and burnt out the platinum contact. Lincoln, the mechanic was very annoyed as a contact cost ten shillings (a week’s wages at the time) and refused to provide me with another for a month. I could never have exploited my ideas about X-ray diffraction under such conditions.1

On the detection side too, the X-ray spectrometer at Leeds, built by his father, was far superior to the Laue-film set-up he had used earlier in Cambridge, and so he continued his work immediately in 1912 at Leeds. The crystals were ‘supplied’ by the Mineralogy Department at Cambridge – the Professor of Mineralogy had given strict orders that no minerals should ever leave the collections, but Arthur Hutchinson, who was then a lecturer in the Department, smuggled them out for Bragg. The structures of the selected halides, and of zinc blende (ZnS), fluorspar (CaF), iron pyrites (FeS) and calcite (CaCO3) were published in 1913, but further work was interrupted by the start of the First World War in 1914.

Bragg spent most of the war working on a system of locating enemy guns by recording the arrival of their sounds at different places. Among the problems to solve were the identification of the sound of one particular gun, to distinguish between its report and the associated shock wave, and also to find a way of recording the time intervals precisely. The problems were solved sufficiently well that a fairly reliable system was in use from the beginning of 1917.

It was during this work, in 1915, that Bragg heard that he and his father had been jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, Bragg for his work on diffraction and crystal structure and his father for his study on the origin and properties of X-rays. Bragg’s ideas on X-ray diffraction and his immediate application in using them to solve structures had made a great impression. It now became possible to establish structure at the atomic level. It was soon applied and resulted in dramatic advances in chemistry, mineralogy and metallurgy, and, more than a decade later, in biology.

After the war, Bragg (the son) succeeded Rutherford in the Physics Chair at Manchester – Rutherford having been appointed the Cavendish Professor at Cambridge. One of the people that Bragg had consulted on which crystals to investigate was the crystal-smuggler Hutchinson, who had remained greatly interested in the X-ray diffraction side of crystallography, and was now the Mineralogy Professor in Cambridge. In 1921, Hutchinson encouraged a graduate, W.A. (Bill) Astbury, to work with Bragg’s father, W.H. Bragg, who was continuing with X-ray studies, now at University College in London, and in 1923 he similarly advised John Desmond Bernal.

J.D. BERNAL

Bernal was born in Ireland in 1901 into an Irish Catholic family and began his secondary education at the Jesuit public school, Stoneyhurst in Lancashire, but left after three months because no science was taught until the sixth form. He transferred to a Protestant English public school, Bedford School, which he also did not enjoy, but which did teach him chemistry and physics and provided him with a library of books to work through and a telescope to watch the stars. In his last year, he was shown Einstein’s early papers on general relativity, and these impressed on him the changing nature of scientific knowledge. He came to Cambridge in 1919 with a mathematical scholarship to Emmanuel College and, because of his wide-ranging interests and knowledge, soon acquired the nickname ‘Sage’ – a name that remained with him for the rest of his life. Another lifetime acquisition was a belief in Marxism inspired by a talk by Henry Dickinson, the son of the curator of the Science Museum. The exuberance and enthusiasm of Bernal was later used by C.P. Snow as the basis of the character of Constantine in his novel The Search, published in 1934 – Constantine is on a committee trying to set up a National Institute of Biophysical Research.2

During his undergraduate studies in Mineralogy and Geology, Bernal had become fascinated with crystallography, and in particular with working out the various possible ways in which atoms or groups of them could be arranged regularly to form crystals – he re-derived algebraically, in his final year, the 230 ways of doing this, the 230 Space Groups. W.H. Bragg had now moved to the Royal Institution in London and Bernal joined his group there in the Davy-Faraday Laboratory in 1923. Bernal would later tell how he had diffidently asked WHB what he thought of his thesis on space groups. WHB replied, ‘Good God man, you don’t think I read it’ – the first page evidently being sufficient to show that he was worth encouraging in research.3

Both Astbury and Bernal were interested in pushing the X-ray technique towards biologically interesting molecules and in particular to proteins. Astbury concentrated on fibrous specimens and obtained X-ray fibre diagrams from wool and silk. Bernal investigated non-fibrous proteins and tried to get X-ray powder photographs from dried specimens of edestin, insulin and haemoglobin, but only obtained obscure bands.

2. J.D. Bernal, 1932. Photo: Lettice Ramsey. Courtesy of Peter Lofts Photography.

In 1926, Hutchinson succeeded in creating the post of Lecturer in Structural Crystallography in the Mineralogy Department, for which both Astbury and Bernal applied. Bernal was successful and so returned to Cambridge. Thus in addition to supplying crystals for Bragg to develop the early X-ray diffraction work, Hutchinson played quite an important part in propagating the technique in Cambridge. Shortly after this, Astbury went to Leeds and began X-ray studies there.

Both Astbury and Bernal were still keen to try to get better X-ray results from proteins. Astbury was sent some crystals of pepsin from America for X-raying, but obtained very limited diffraction patterns from crystals carefully dried (and as a result, disordered!). On the fibre side he was more successful, and in 1934 published a long paper on the structure of hair, wool and related keratin fibres, demonstrating a contracted (α-) form and an extended (β-) form. It was suggested that both were built from extended polypeptide chains that became more pulled out in the β-form. The structure proposed for the α-form, although plausible, was incorrect, and the true α-helical structure was proposed by Pauling in 1951. However, in the 1934 paper, Astbury correctly proposed the β-structure of stretched out chains packed together to form β-sheets.

Bernal, in Cambridge, concentrated on crystals of the smaller globular proteins. In 1934 he was sent some crystals of pepsin from Uppsala. The grower, John Philpot from Oxford, had taken specimens there for centrifugation, and while he had been on holiday, crystals had grown up to 2mm in size. Again, dried crystals gave very disappointing results, but Bernal, following their drying in a microscope, could see that the crystals deteriorated considerably. There were some thin-walled glass capillaries being used in the laboratory for investigating ice crystals, so Bernal mounted a wet pepsin crystal into one of these, sealed it and obtained the first X-ray diffraction pattern from a well-ordered protein crystal – a film covered with spots from the diffracted beams. He was able to determine the unit cell as hexagonal with sides 67A × 67A × something much larger. Dorothy Hodgkin (then Dorothy Crowfoot) was a visitor to Bernal’s group at that time from Oxford, and took further photographs. Notes of their results with the pepsin crystals and those of Astbury were published in Nature. The original Cambridge X-ray films have been lost; they probably went to Birkbeck College in London with Bernal in 1938 and were destroyed in the bombing of the College buildings during the war.

In 1934, Dorothy returned to Oxford, and her work in Cambridge was taken over by an American visitor, Isidor Fankuchen. Then, in 1936, Max Perutz joined the group. In the next four years, X-ray measurements were made on five different proteins: insulin and lactoglobulin (Crowfoot and Dennis Riley at Oxford), excelsin (Astbury, Dickinson and Bailey at Leeds) and chymotrypsin and haemoglobin (Bernal, Fankuchen and Perutz in Cambridge).

MAX PERUTZ

Max Perutz was born in Vienna in 1914. He was educated at the Theresianum (a grammar school originating from an earlier officers’ academy). His parents suggested that he study law to prepare for entering the family business, but when a master sparked his interest in chemistry, he was allowed to change accordingly. In 1932, he entered Vienna University ‘wasting five semesters in an exacting course of inorganic analysis’. His curiosity was aroused, however, by a course in organic chemistry in which the work of Frederick Gowland Hopkins in Cambridge on vitamins and enzymes was mentioned, and Max decided that Cambridge was the place where he wanted to work for his PhD.

The professor of physical chemistry in Vienna was Hermann Mark, a co-founder of polymer science who had shown that most polymers were flexible chains and had used X-ray diffraction in his studies. When Max heard that Mark was to visit Cambridge in 1935, he asked him to see if there was a place for him as a research student in the Biochemistry Department. Mark forgot about this when he was in Cambridge, but he had met Bernal and heard of his latest X-ray results and also that he would be willing to take on a student. Max knew nothing about crystallography but was attracted by hearing that it was being applied by Bernal to biological specimens. With financial help from his father, he joined Bernal’s group in 1936 as a research student.

Bernal was away when he arrived in Cambridge and he was met by Fankuchen with the question ‘What’s your religion?’ which took Max aback – his father had warned him never to ask an Englishman personal questions. His answer ‘Roman Catholic’ provoked the response ‘Don’t you know the Pope is a bloody murderer’. Fankuchen, like Bernal, was a devout Communist, and his denunciation referred to the Pope’s support for Franco in the Spanish Civil War. He regarded Max as a Capitalist because of his father’s gift of £500 for his studies (this paid for living expenses and university fees for two years plus a term). However, between efforts to convert Max to communism, Fankuchen taught him some useful crystallography.4

At that point, Bernal had no useful biological specimens and Max was disappointed at being given some mineral specimens on which to cut his crystallographic teeth, but he remembered that ‘Bernal’s brilliance and boundless optimism about the powers of the X-ray method transformed the dingy rooms in the dilapidated grey-brick building into a fairy castle’5 and, despite the minerals, he fell in love with Cambridge and remained there for the rest of his life.

3. Max Perutz at the conference on crystallographic computing held at Pennsylvania State University, 1950. Courtesy of Special Collections, Penn State University.

Max’s study of haemoglobin began after a summer holiday in 1937. He visited a cousin in Prague who was married to a professor of physical chemistry, Felix Haurowitz, who had studied the chemistry of haemoglobin and other proteins. Haurowitz suggested haemoglobin as a protein whose structure should be solved and Gilbert Adair, a physiologist in Cambridge, as someone who might well be able to supply some crystals for diffraction. On his return to Cambridge, Max approached Adair (after being properly introduced at a lunch party arranged by F.G. Hopkins’ daughter, Barbara Holmes6) and, shortly after, Adair produced some suitable crystals of horse haemoglobin. Bernal and Fankuchen showed him how to mount them for X-raying, and also some chymotrypsin crystals that had been sent to Bernal by John Howard Northrop at the Rockefeller Institute. Max took X-ray pictures of both and determined their crystallographic parameters – the unit cell sizes and their space groups. This was really as far as one could go then. These parameters were sufficient to define the structures of the simplest crystals, with only one or two atoms per molecule. For the slightly more complex minerals with about a dozen atoms per molecule, the structure could be deduced from trial models – comparing the predicted and observed X-ray patterns. But no one knew what to expect for the structure of a protein molecule with hundreds or thousands of atoms. The detailed X-ray patterns did show, however, that the protein molecules in the crystals had a well-defined structure waiting to be determined.

Crystallography had been transferred from Mineralogy to the Cavendish Laboratory in 1931, probably not to the liking of Rutherford, the Cavendish Professor. Max recalled being disappointed that Rutherford never visited their group and assumed that he was only interested in atomic physics. But in fact,

the conservative and puritanical Rutherford detested the undisciplined Bernal who was a Communist and a woman chaser and let his scientific imagination run wild. He had wanted to throw Bernal out of the Cavendish but was restrained from doing so by Bragg. If Bragg had not intervened, Bernal’s pioneering work in molecular biology would not have started, John Kendrew and I would not have solved the structure of proteins, and Watson and Crick would not have met.7

Rutherford died in October 1937. Earlier in the year there had been a general professorial rearrangement. Bragg had moved from Manchester to the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in London. He was succeeded in Manchester by Patrick Blackett from the Physics Department at Birkbeck College in London, and Bernal moved from the Cavendish to replace him at Birkbeck. Bragg had soon found the work at the NPL very disappointing, and when offered the Cavendish chair accepted it and moved to Cambridge in 1938.

Bernal had taken Fankuchen with him to Birkbeck, and so the only biological crystallographer left at the Cavendish was Max. He waited for a few weeks for Bragg to visit him after his arrival and then plucked up courage to call on him and show him the X-ray pictures from haemoglobin. Bragg was immediately enthused by the prospect of extending the X-ray diffraction method to biological molecules, and within three months had obtained a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to continue the work and appointed Max his research assistant. This salary was vital for Max to continue his work – his parents, who had come to England to escape the effect of the Anschluss in Austria, could no longer provide for him, and in fact his salary enabled him to provide for them. However, his status was changed from a guest to a refugee, and because of the unemployment situation, he was not allowed to earn money in England – even as a college supervisor. However, he could receive the Rockefeller money, since it was from the USA and was designated specifically for him.

The Rockefeller Foundation also bought me an X-ray tube for £99 and provided a modest supply grant. People often grumble now that it has become harder to get money for research, but they never knew those days when there just was not any. The Rockefeller Foundation supported all the pioneers in the subject for which Warren Weaver, its director of natural sciences, first coined the term ‘molecular biology’ in 1938. These included Theo Svedberg, Arne Tiselius, Kaj Linderstrom Lang, Bill Astbury and David Keilin. I remember the joy at the Molteno Institute when the Foundation bought Keilin the first Beckman spectrophotometer.8

Max was a keen mountaineer and skier and managed to spend the summer of 1938 in Switzerland with a travel grant to study glacier structure and flow, the results of which were published in the following year. When asked how, with such a love of the alpine, he could bear to live in flat, fenland Cambridge, he said he could enjoy wonderful holidays on the continent while living in Cambridge, but the reverse was not quite so tempting.

4. Max Perutz studying thin sections of glacier ice on the Jungfraujoch, 1938. Courtesy of Vivien and Robin Perutz.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, most of the staff at the Cavendish became involved in war work, but Max, as an alien, was not immediately accepted for this. On the contrary, in 1940 he was arrested with about 100 others from Cambridge, and detained locally for a few weeks. They were then taken to join some 1,200 others before being transported by ship under dangerous and atrocious conditions to Canada. Max was interned in camps for some months with a group which included many other talented aliens, including Herman Bondi and Thomas Gold (who both later became professors with chairs in astronomy and maths) and organised a Camp University with these as teachers. He was allowed to return to Cambridge in 1941, and he wrote a striking account of this part of his life for the New Yorker magazine in 1985, reprinted in his book Is Science Necessary?9

Back in Cambridge, he met Gisela, herself a refugee, who was working for the Academic Assistance Council, which had been set up in 1933 to assist academic refugees. Max and Gisela were married in 1942. Later that year, as a consequence of his glaciology work, he became involved in Habakkuk – one of the schemes thought up by the eccentric man of ideas, Geoffrey Pyke. The aim of the project was to build assault weapons that could be used on ice and on the development of ‘pykrete’, a frozen mix of water and sawdust that Pyke thought could be used to build vast floating ‘berg ships’ and even a floating airbase. Research began in a large cold store in Smithfield Meat Market in London, and parallel work in Canada got as far as a model ice ship with insulation and refrigeration on Lake Patricia in Alberta. However, pykrete, like glaciers, suffered from creep and this, with other disadvantages and the fact that aircraft with larger ranges had been developed, doomed the project, and Max returned to Cambridge to continue his work on haemoglobin. He was joined in 1946 by John Kendrew.

JOHN KENDREW

John Kendrew was born in Oxford in 1917 and educated at the Dragon School and Clifton College, where an interest in chemistry persuaded him to focus on science and thus to aim for a place at Cambridge, which was then the ‘real scientific university’.

Coming to Cambridge in 1935 for the scholarship exam, he found the facilities at Cambridge in the practical laboratories were very primitive compared to the modern science laboratories at Clifton. The Chemistry laboratory was lit by gas, and although the Cavendish had electricity, the equipment was very ancient. Towards the end of the exam, an old man came and sat by him and asked if he was interested in football – which he was not, since this was before the introduction of plastic lenses and John’s eyesight was not good. Afterwards, the head assistant told him, ‘Sir, that was Sir J.J. Thomson, Master of Trinity’, and of course the most famous physicist of the Cavendish – he made a practice of talking to anyone who had put down Trinity and physics in their applications.10

John Kendrew was awarded a scholarship to Trinity College and graduated in chemistry in 1939. He began working for a PhD in physical chemistry, but this was soon interrupted by the war. He was diverted initially to work on radar, and then to more general operational research – as scientific adviser attached to one of the operational headquarters. He ended the war on the staff of Lord Mountbatten’s South East Asian Command in Ceylon. This was a vital posting for Kendrew’s future, since it brought him into contact with Bernal. Mountbatten and Bernal were good friends – Mountbatten was quite left-wing and sympathetic to Bernal’s communist views, and Bernal was often called in for discussions and advice. It was during one of these visits that Bernal talked with Kendrew about how it should be possible to use X-rays to solve the structure of proteins and understand their biological functions. This so impressed Kendrew that he became keen to work in this field after the war. Bernal offered him a place in his laboratory at Birkbeck, but added that being a communist, it might be difficult for him to raise money for research and that Kendrew would do better to finish his Trinity scholarship in Cambridge and so directed him to Bragg and hence to Max.

5. John Kendrew at the Pasadena Conference on the Structure of Proteins, 1953. Courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of Technology.

Max was a little embarrassed by Kendrew’s approach, since his work on the structure of haemoglobin did not seem to indicate that this was a quick route to a PhD. However, on meeting Joseph Barcroft, the distinguished respiratory physiologist who was working at the nearby Molteno Institute for Parasitology and discussing the problem, Barcroft suggested a comparative study of adult and foetal sheep haemoglobin for which he could supply the blood. Kendrew was keen to become involved in the work, agreed to this project and became effectively Max’s research student, although nominally under the direction of the Cavendish mineral crystallographer, W.H. Taylor.

The overall financial position at this stage was rather precarious. Kendrew’s grant had two years to run and Max had been awarded an ICI fellowship, but this was again only for two years. Although Bragg had recommended Max for a University Lectureship, it took nine years to materialise. Max put this down to being a misfit – a chemist in a physics department working on a biological problem. However, it did give him the freedom to concentrate on his research. But for the future, while the Rockefeller grant provided vital money for equipment, etc., the Foundation thought that the University should provide Max’s salary. So, between these, Max was out of a firm job.

1. W.L. Bragg, 1975. The Development of X-Ray Analysis. G. Bell and Sons Ltd, London, p. 54.

2. C.P. Snow, 1934. The Search. Victor Gollancz, London.

3. D. Hodgkin, 1980. John Desmond Bernal. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 26, 17–84.

4. Max in his retirement lecture, 1979, reproduced in New Scientist, 85, 31 January 1980, 326–329.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. M.F. Perutz, 1989. Is Science Necessary? Essays on Science and Scientists. Barrie and Jenkins, London.

10. In an interview with Ken Holmes at LMB in 1996.

Short biographies of Bragg, Bernal, Perutz and Kendrew are recorded in the BiographicalMemoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society:

Bragg, by David Phillips in 25, 75–136, 1979.

Bernal, by Dorothy Hodgkin in 26, 17–84, 1980.

Perutz, by David Blow in 50, 227–256, 2004.

Kendrew, by Ken Holmes in 47, 311–332, 2001.

Max gave a biographical talk to the Peterhouse Kelvin Club in 1996 which was video-recorded.

A longer biography of Bernal was written by Andrew Brown in 2005: J.D. Bernal: The Sage of Science (Oxford University Press, Oxford), and one of Max by Georgina Ferry in 2007: Max Perutz and the Secret of Life (Chatto and Windus, London).

CHAPTER TWO

The MRC Unit

The MRC began funding the unit in 1947, and it soon attracted students and visitors to work on haemoglobin and myoglobin. Hugh Huxley joined the unit in 1948, but soon became diverted into muscle research. Francis Crick joined in 1949. In 1953 there was a breakthrough in the X-ray diffraction work – Max showed how the structures of proteins could be solved by attaching heavy atoms to the molecules in the crystals. In 1957, myoglobin became the first protein to have its structure solved in this way by John Kendrew’s group. The larger molecule, haemoglobin, was solved by Max’s group in 1959; David Blow and Michael Rossmann were both involved in this.

MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL UNIT FOR THE STUDY OF THE MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS

The financial plights of Max Perutz and John Kendrew were overcome with the help of David Keilin, another distinguished Cambridge scientist. Keilin was a Russian-born biologist who had discovered the cytochromes and was the head of the Molteno Institute (a parasitology institute on the Downing site of the University off Free School Lane in Cambridge, set up in 1921, but incorporated into the Department of Pathology in 1987). Keilin had given Max and John bench space for their preparation of crystals. (Keilin was a very keen experimentalist and disapproved of theoreticians and, later, particularly of Crick. ‘Keep him to the bench’, he advised1.) Max told him of their financial situation and that he thought he would have to find a job in industry. Keilin, who was friendly with Sir Edward Mellanby, the Secretary (the Executive Head) of the Medical Research Council, suggested that Bragg approach Mellanby for financial support. A meeting was arranged between them in the spring of 1947 at the Athenaeum Club, Mellanby submitted a paper to the Council for a ‘preliminary run’ and to his surprise the project was immediately adopted at their meeting in October 1947, establishing in the Cavendish Laboratory the ‘Medical Research Council Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems’. The grant was for £2,550, rising to £2,650 per annum, to support Max and John and two research assistants for five years.

No one seemed very keen on the name. The address in papers continued mainly to be ‘Cavendish Laboratory’, though Max’s paper in 1951 on the 1.5Å reflection from the α-helix gave the complete title. There was some discussion on the matter in 1953. Harold Himsworth, who had taken over from Mellanby as Secretary of the MRC in 1949, suggested ‘Bio-molecular Research Unit’. Frank Young, the head of the Biochemistry Department, thought this rather vague and suggested ‘Unit for Research on Bio-molecular Structure’, but Max had a strong dislike for ‘bio-molecular’ and suggested ‘Unit for Biological Structures’. The subject was then dropped. From 1953 to 1958, the complete earlier name tended to be used, but from 1958, the ‘MRC Unit for Molecular Biology’ became preferred. Warren Weaver’s term ‘Molecular Biology’ was adopted as a compact title, and distinct from ‘Biomolecular Structure’, the name of Astbury’s department in Leeds.2

The first research student attracted to the Unit was Hugh Huxley (1948), who began work on myoglobin but soon became more interested in muscle. His PhD supervisor was John Kendrew, who was then only one year into his own PhD. Francis Crick (1949), David Green (1953) and David Blow (1954) were all supervised by Max, with haemoglobin as their main subjects, although Francis was diverted into working on helical diffraction theory and coiled-coils and, when Jim Watson appeared in 1951, into DNA (chapter 3).

HUGH HUXLEY3

Hugh Huxley joined the Unit in 1948. As a schoolboy in Birkenhead in the 1930s, he became enthralled with the discoveries in atomic and nuclear physics and since Rutherford’s laboratory was at the forefront of this work, Cambridge became his aim, which he achieved as an undergraduate in 1941. Although his ultimate aim was to do nuclear physics research, and in his second year he was able to go directly to Part II physics, he felt the need to be more closely involved in wartime events and in 1943 joined the RAF as a radar officer. The news of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan had a devastating effect on his desire to do nuclear physics research. Although on his return to Cambridge in 1947 he continued with Part II physics, and gained a first in the Tripos, making him eligible for a research studentship, he wanted to be far from the wartime applications. He was attracted more towards medical research, and so, in 1948, he joined the MRC Unit as a PhD student.

At first, he was incorporated into the team collecting X-ray data from myoglobin and haemoglobin, but reading about the problems of muscle structure and of the mechanism of its contraction, he became very interested in this. In particular, following the earlier experience of the protein crystallographers, there was the possibility of getting informative X-ray patterns from wet muscle specimens. John Kendrew had earlier suggested using a microcamera with a glass capillary collimator together with a microfocus X-ray tube, of the type being developed by Ehrenberg and Spear in Bernal’s laboratory at Birkbeck, to look at diffraction from small biological specimens. Kendrew’s friendship with Bernal yielded an early prototype of the X-ray tube. By that time, Hugh had decided to do low-angle diffraction on muscle using a miniaturised slit camera, and for this the microfocus tube was an excellent source, and he soon obtained X-ray patterns.

6. Cavendish staff in 1952 (section). In the second row from the front, Hugh Huxley, Jim Watson and Francis Crick are first, second and third from the left, and John Kendrew is first from the right. In the back row, Aaron Klug is on the extreme right.

Courtesy of the Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge.

The first of these gave a number of equatorial reflections (i.e. perpendicular to the muscle fibrils) based on a hexagonal side of 400–450Å, which he interpreted as arising from a hexagonal array of contractile filaments, parallel to the length of the fibril. Later, with muscles in rigor (stiffened by lack of ATP), he found the same lattice but with considerably altered intensities, indicating a large lateral movement of material within the fibril. Hugh’s interpretation, that the myosin filaments were located at the hexagonal lattice points with the actin filaments between – near the trigonal points – and becoming more fixed there in rigor by crosslinks, was broadly correct, except that the filaments are not continuous throughout the length of a muscle fibril, and it is largely the movement of the crosslinking material which changes the intensities of the hexagonal reflections.

Hugh found that the muscles of local Cambridgeshire Fen frogs gave stronger X-ray patterns than the laboratory-bred ones, especially in the meridional regions (along the length of the fibrils). Surprisingly, the spacings of these reflections did not alter as the relaxed muscle was stretched, and it was not clear how to assign them to the myosin and actin components.

After getting his PhD, Hugh went to MIT to learn electron microscopy at Frank Schmitt’s laboratory and produced micrographs of cross-sections of fibrils showing the hexagonal array of filaments he had predicted from the X-ray work and suggestions of the crossbridges between them. A fellow visitor to the MIT laboratory in 1953 was Jean Hanson, who had been using the relatively new technique of phase contrast microscopy to photograph various types of muscle fibrils at King’s College in London. Between them they established that the dense A-bands in longitudinal sections of muscle fibrils were not due to some material extra to myosin and actin filaments, but defined the location of the myosin filaments. Hugh pointed out that these results and his earlier X-ray data on constant axial periodicities were consistent with the sliding of the two types of filament past each other during stretching and possibly a similar process could occur during contraction. Later, they obtained evidence from band-pattern changes in isolated myofibrils that this was indeed what happened during contraction, and proposed the ‘Sliding Filament Model’,4 simultaneously with a similar proposal from Andrew (A.F.) Huxley (no relation) and R. Niedergerke in the Physiology Department in Cambridge.

In 1954, both Hugh and Jean returned to England – Hugh at first back to Cambridge and then at the end of 1955 to the Biophysics Department at University College in London. He continued with the electron microscope work begun at MIT – looking at sections of embedded muscle specimens, sufficiently thin that with accurate alignment of the plane of sectioning, single thick and thin filaments could be seen and, clearly, the cross-bridges between them, in excellent agreement with the interdigitating, sliding filament model proposed earlier.

University College was close to Birkbeck College and, encouraged by Rosalind Franklin and Aaron Klug there, Hugh began looking at viruses in the electron microscope. In 1956, he found by chance that if tobacco mosaic virus were dried onto the carbon substrate from a solution containing phosphotungstic acid (or sometimes it happened with potassium chloride), the extra density produced by the dried salt showed a central hole along the rod-shaped particle. Cecil Hall at MIT had also noticed the effect with ‘insufficiently washed’ specimens of stained tomato bushy stunt virus. These were the first examples of negative staining in electron microscopy (surrounding and infusing a relatively low density biological specimen with a dense salt and so outlining the specimen in an electron beam). The method was developed in 1959 by Sydney Brenner in the MRC Unit with Bob Horne in the Cavendish, using sodium phosphotungstate as the stain, and in 1960 by Hugh using uranyl acetate. With the latter, he and Geoffrey Zubay produced images of ribosomes and of the small, spherical virus turnip yellow mosaic, showing the icosahedral pattern of the protein subunits on the surface of the virus particle. Hugh returned to Cambridge, to the new LMB, in February 1962.

THE PHASE PROBLEM

After taking the haemoglobin project of his PhD research as far as was then possible, John Kendrew took up the problem of myoglobin, a smaller protein that stored oxygen for use when muscles do work. Myoglobin is about a quarter of the size of haemoglobin and therefore seemed more hopeful to pursue by X-ray diffraction. His first source, horse heart, provided little material and what there was grew poor crystals. They gave sufficient data to complete his thesis, but, with Bob Parrish, an early visitor, he began a survey of 24 different species, including diving mammals – he realised that these offered a good prospect since a tenth of their dry muscle weight is myoglobin needed for oxygen supplies during long undersea dives. Sperm whale looked promising; a chunk of sperm whale meat was located, and the myoglobin from this yielded large crystals which gave beautiful diffraction patterns.

As far as structure determination was concerned, both haemoglobin and myoglobin were more or less stuck at this point by the basic ‘phase problem’ of X-ray diffraction. The diffraction pattern records the intensities of the diffracted rays. The square roots of these intensities, the amplitudes, are proportional to the magnitudes of the sinusoidal electron density waves (the Fourier components) into which the crystal contents can be analysed – it is electron density that is measured, since it is electrons that scatter the X-rays. In order to build up a picture of the crystal structure in terms of the overall electron density variations in the crystal (a Fourier map), one has to combine the Fourier components in their correct spatial relationship, i.e. one needs to know the position, as indicated by the phase of each component wave, relative to some fixed point in the crystal. (The phase is expressed as an angle – the whole period of any one of the component sinusoidal electron density waves corresponds to 360° and so, in general, each wave can have any phase angle between 0° and 360°. Mathematically, the electron density is the Fourier transform of the complex amplitudes, i.e. including phases). Without the phases, only Patterson maps can be calculated. Patterson maps, which are the Fourier transforms of the distribution of the intensities of the X-ray reflections, show the distribution of vectors between atoms in the crystal and for large molecules they are not easily interpretable. The method commonly used for computing Fourier and Patterson maps at that time was with Beevers-Lipson strips on which the Fourier components were tabulated. The strips corresponding to a particular line in the map were aligned and the numbers in the columns summed with, at that time, a rather noisy adding machine, to give the values of the map along that line.

During the war (1942–3), Max had collected 7,000 reflections from haemoglobin crystals, out to a resolution of 2.8Å. These were recorded on films whose exposure times were one to two hours, and three sets of 45, 3° oscillation photographs about three different axes were taken. Sometimes he continued collecting all night when he was on duty fire-watching in the Cavendish (a wartime Civil Defence occupation), changing the film every two hours. The intensities were measured by eye – by comparing with a record on film of a reflection from an anthracene crystal exposed for different times. This task was shared with two assistants, Joy Boyes-Watson and Edna Davidson.

To calculate the Patterson map, Max began by using Beevers-Lipson strips, and with these it was only feasible to use the limited projection data and calculate the Patterson projections which were published in 1947. But the complete three-dimensional Patterson map was then calculated and published in 1949, the summation being made in London using a Hollerith punched card tabulator.

Overall, the interpretation of this map from such a large structure was not clear, but there was evidence for polypeptide chains in the proteins similar to those indicated in Astbury’s X-ray pattern from α-keratin. Max concluded ‘rashly’5 that haemoglobin was constructed of a set of close-packed α-keratin-like chains parallel to the crystallographic a-axis. Shortly after this, Francis Crick joined the group and calculated that the density in the vector rod in the Patterson map interpreted on this basis was considerably lower than the interpretation required, and when the real structure emerged seven years later, it became clear that this vector rod arose from one of the α-helical stretches in the molecule (the G-helix) which makes up only 7 per cent of the molecule.

In 1950, Bragg, Kendrew and Perutz proposed a tentative common structure for proteins, but they did not consider non-integral helices and their argument was also flawed by allowing free rotation about the peptide bond. Later that year, Linus Pauling and Robert Corey pointed out this flaw and proposed two possible helical arrangements which fitted the available data. One of these was the α-helix with 3.6 amino acids per turn of the helix and pitch 5.4Å. Reading this in PNAS one Saturday morning at the Cavendish, Max was convinced of the existence of the α-helix, and was so angry at their making the earlier mistake that he immediately checked the prediction of the α-helical arrangement that there would be a 1.5Å reflection on the meridian of the X-ray fibre diagram by setting up a horse hair on the X-ray camera in the appropriate orientation. On being shown the reflection in the resulting picture and learning of Max’s anger, Bragg commented, ‘I wish I had made you angry earlier’, a response used by Max for the title of his book of essays nearly 50 years later.6

THE PHASE PROBLEM SOLVED

In 1952, Bragg deduced the molecular shape of haemoglobin from variations in the intensities of the low resolution reflections with salt concentration, arriving at a spheroid with axial lengths 55×55×65Å. But the general way to solve the phase problem for proteins, by incorporating heavy atoms, was demonstrated by Max in 1953. Bernal, in a lecture at the Royal Institution in 1939, had indicated that this would in theory be the way to go, but without going into details of its practicality. Heavy atoms had already been used with smaller structures. Since they dominated the scattering density, the phases of the diffracted rays could all be taken, at least to a first approximation, to give a maximum at the heavy atom position, leading to a density map which could be interpreted and refined. This was not directly possible with a structure as big as a protein, and it was generally assumed that for such a big molecule the intensity differences in the diffraction pattern produced by a heavy atom would be too small to measure. However, Max measured the absolute amplitudes of the diffracted rays from a haemoglobin crystal relative to the incident beam and found that they were surprisingly low – the rays scattered by the many light atoms in the protein were more-or-less in random phase with respect to each other and so tended to cancel each other. As a result, a concentrated bunch of electrons at a heavy atom should in fact stand out and be detectable, and hence produce phase information. During the 1940s, Max had shared an office with Arthur Wilson, who was developing the statistics which were named after him, and which could have been used to calculate the absolute values of the intensities rather than determine them practically, ‘but at that time I was busy collecting data for the three-dimensional Patterson, and it never occurred to me that Wilson’s calculation would be relevant to the phase problem in haemoglobin, so that I had to determine the absolute intensities by laborious experiments’.7

In 1953, Max received a reprint from Austin Riggs, a biochemist at Harvard who was investigating possible differences between normal and sickle-cell haemoglobins. In the course of this he had shown that mercury atoms could be attached to sulphydryl groups on haemoglobin without affecting its oxygen uptake, and Max realised that this indicated that the structure had not been disturbed and if it crystallised was just what was required.

Vernon Ingram, a chemist in the group, made some of the mercury compound, and it was attached to haemoglobin before crystallisation. Max saw that the resulting X-ray picture had clear changes in the intensities of the reflections compared to those from native crystals, and when he showed it to Bragg, they both realised that this was indeed the way in which protein structures could be solved. With his student David Green, the locations of the mercury atoms in the unit cell were found and the signs of the 0kl reflections determined. (These reflections correspond to the projection of the crystal down its two-fold axis, and they can only have phases of 0° (plus) or 180° (minus) – the Fourier component cosine waves of density can only have peaks or troughs centred on a two-fold axis.) The paper recording this was published by the Royal Society in 1954,8 and the same year Max was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Although it was possible to calculate the phases and the density map corresponding to the projection down the two-fold axis of the haemoglobin crystal, the high density of atoms made it uninterpretable. Dorothy Hodgkin, visiting the laboratory to see the result, mentioned to Max that, in a recent paper, the Dutch crystallographer Bijvoet had pointed out that with two heavy atom derivatives one could determine all the phases. The search therefore began for more heavy atom derivatives. But, in pursuing the technique into three dimensions, the work on myoglobin had the advantage of a smaller sized molecule giving more robust crystals and simpler diffraction patterns.

THE STRUCTURE OF MYOGLOBIN

In 1951, John Kendrew had prospected in the USA for postdocs to amplify the work on myoglobin. One of the first visitors resulting from this was Jim Watson, but his lack of success in crystallising the protein left him time to think more about DNA. Another early visitor was Bob Parrish, who had helped John with the survey of different species of myoglobin – various whales, seal, penguin, carp and horse – for the most suitable crystals to pursue by X-ray diffraction.

After Max had demonstrated the feasibility of using the heavy atom procedure to phase the X-ray reflections from proteins, Gerhard Bodo and a heavy atom chemist, Howard Dintzis, were recruited by Kendrew to join the Unit in 1954. Dintzis specialised in complexes containing heavy atoms and the hope was that these might form a loose combination with the protein at preferred specific sites – it was largely hit-and-miss, since myoglobin has no sulphydryl groups. Some of these were successful and led to the first map of the structure at 6Å resolution in 1957. Five different heavy atom sites were found and the phases corresponding