Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: The Wanderer Chronicles

- Sprache: Englisch

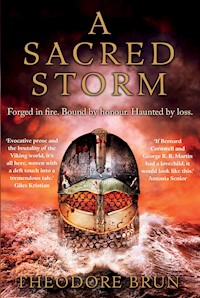

Book II of the Wanderer Chronicles 'A masterly debut... If Bernard Cornwall and George RR Martin had a lovechild, it would look like A Mighty Dawn. I devoured it late into the night, and eagerly await the sequel.' -- Antonia Senior on A Mighty Dawn Forged in fire. Bound by honour. Haunted by loss. 8th Century Sweden: Erlan Aurvandil, a Viking outlander, has pledged his sword to Sviggar Ivarsson, King of the Sveärs. But violence is stirring in the borderlands. As the fires of an ancient feud are reignited, Erlan is bound by honour and oath to stand with King Sviggar. But, unbeknownst to the old King his daughter, Princess Lilla, has fallen under Erlan's spell. As the armies gather Erlan and Lilla must choose between their duty to Sviggar and their love for each other. Blooded young, betrayed often, Erlan is no stranger to battle. And hidden in the shadows, there are always those determined to bring about the maelstrom of war...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 889

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Theodore Brun

A Mighty Dawn

Theodore Brun studied Dark Age archaeology at Cambridge. In 2010, he quit his job as an arbitration lawyer in Hong Kong and cycled 10,000 miles across Asia and Europe to his home in Norfolk. A Sacred Storm is his second novel.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This edition published in 2019.

Copyright © Theodore Brun, 2018

The moral right of Theodore Brun to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 003 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 000 1

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

This one’s for Tash.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

AT THE HALLS OF UPPSALA, SVEÄLAND:

Sviggar Ívarsson – King of the Sveärs

Lady Saldas – Queen of the Sveärs and Sviggar’s second wife

Svein & Katla – their infant children

Sigurd Sviggarsson – Prince of Sveäland and heir apparent

Vargalf – his personal oathman

Aslíf Sviggarsdottír, known as Lilla – Princess of Sveäland

Erlan Aurvandil – the king’s bodyguard and member of the Council of Nine

Kai Askarsson – his servant

Huldir Hoskursson – Earl of Nairka and member of the Council of Nine

Gettir Huldirsson – known as “the Black” – one of Huldir’s two surviving sons

Gellir Huldirsson – known as “the White” – his twin brother

Bodvar Beriksson – Earl of Vestmanland and member of the Council of Nine

Bara Ballirsdottír – handmaiden to Queen Saldas

Einar the Fat-Bellied – a king’s karl

Jovard – a king’s karl

Aleif Red-Cheeks – a king’s karl

Vithar Lotharsson – a goði and member of the Council of Nine

Rissa – a serving-thrall

AT THE HALL OF DANNERBORG, EASTERN GOTARLAND:

Ringast Haraldarsson – Lord of Eastern Gotarland, Prince of Danmark and eldest son to Harald Wartooth, King of the Danes

Thrand Haraldarsson – Prince of Danmark and second son to King Harald

Rorik Haraldarsson – Prince of Danmark and third son to King Harald

Sletti – the steward of Dannerborg

Ubbi the Hundred – a warrior mercenary from Friesland and Prince Ringast’s guest at Dannerborg

Visma – a Wendish shieldmaiden Duk – her husband

Gerutha – a servant-woman

Grim & Geir of Hedmark – cousins and mercenaries

AT THE HALL OF LEITHRA, DANMARK :

Harald Roriksson – known as “the Wartooth” – King of the Danes

Branni – his oathman, councillor and oldest friend

PROLOGUE

He is dying and he knows it.

In the slanting rays of a falling sun his horse’s shoulder glistens with blood soaked through his breeches.

His comrades are dead. But somehow he got away. Got this far.

He feels cold, despite everything around him signalling a warm spring evening. Golden light, foliage erupting, mocking the numbness creeping through his bones. All the while he hears the whisper of Hel, her breath soft beside his ear. He will slide back into her embrace soon enough, but not before he has done this last service to his king.

He glances down at his wound: an ugly gape in the left of his abdomen. The leather byrnie is torn and through the oozing blood he glimpses the slick greyness of his own entrails. The sweet scent of spring is soured with the reek of open viscera. He has smelled it before – many times in battle, amid the roil of Skogul’s Storm, when the Valkyries ride to carry off the fallen heroes – the einherjar – to Odin’s hearth in the Hall of the Slain.

Valhöll.

Is that to be his glorious reward?

There was nothing glorious about that savage skirmish under the gloomy boughs of the Kolmark forest. Screams of terror, desperate pleas for mercy, bowel-emptying shrieks of pain. There was hardly time to snatch their weapons before half of them were butchered.

How did I get away?

The question haunts him. Perhaps he didn’t. Perhaps he died with the others and Odin has chosen him to deliver this message – has sent him back from the dead, a draugr. A harbinger of death to the living.

There is a rustle in the undergrowth to his right. He looks and sees something moving. A shadow lurking beside him. Is it following him?

He stops. The shadow stops. And then he sees. A wolf? No. A dog – a hound, staring at him with one wide, unblinking eye. The other is an empty socket. A doorway into darkness.

The horse moves on, unbidden. Its sudden movement jars him. When the wave of pain has passed he looks back. But the hound is gone.

Perhaps it was another draugr-spirit, sent by Odin to watch him to his doom.

One eye.

The eye that sees. The eye that calls...

He lifts his own. Their lids are heavy. Through the last of the beech trees, he can see smoke-wreaths swirling into the purpling sky, risen from the hearths of the halls of Uppsala. One roof towers above the others: the Great Hall of Sviggar Ívarsson, the seat from which the old king has ruled over Sveäland for thirty years. The Bastard King, his enemies call him, although to him, Sviggar has been a faithful lord. Honest and generous.

Yet now all his gifts will be paid for in full. Paid with the last drop of blood.

The Great Hall looms like an oak mountain, propped by vast buttresses, each thick as a giant’s forearm. Through the foliage of the Sacred Grove he spies the carving that crowns the gable: a black eagle with a wolf’s head – symbol of Sviggar’s line and now the Sveär people also.

How many feasts have I enjoyed under that roof? How many toasts have I drunk? How many songs have I sung? And the women...

There will be no more of them. Not in this life.

The sun is kissing the horizon. Looking west, he sees the three familiar domes of earth: the King Barrows. Under each is buried an ancient king of the Yngling line. The western half of each mound is bathed in copper light, their eastern halves swaddled in shadow. The first midges of the year dance on the air like sparks from the hearth of the sun. The sparks smear and he realizes his vision is blurring.

A beautiful day to die.

His breathing is a shallow rattle. His horse suddenly lurches into a trot, each rise a stab at the wound in his side. Perhaps the animal senses its home and hay are near; or that its master’s final breath is nearer still. But he mustn’t die yet. Not until he has reached the shadow of the Great Hall. Not until he has found someone.

Not until he has delivered his message.

PART ONE

DAUGHTER OF A KING

CHAPTER ONE

The apple was gone in a blink.

The horse nuzzled his other hand, expecting another.

‘You’re not an easy girl to please, you know that,’ said Erlan Aurvandil, tickling her hoary chin. But Idun loved apples, just like the goddess she was named after.

Gods, but she’s a grumpy-looking beast, he thought. Still, she looked a sight healthier than the bag of bones he’d ridden in on when he first arrived at the halls of the Sveär king. Good eating and rest had seen to that. And the odd apple.

Erlan produced another from his pouch. Idun gobbled it down.

‘Off you go, you old mule,’ he said, thwacking her rump. The horse plodded off to a clump of grass nearby. Erlan, meanwhile, began limping back towards the halls and smaller dwellings, inhaling the sweet, green air. It was one of those evenings that seemed swollen with life, a foretaste of summer, when even the pain in his ankle felt not quite so sharp. As if, one day, it might heal.

Of course, it never would.

The limp was his father’s mistake. He hadn’t known the rock lay under the sand waiting to change his son’s destiny. ‘Jump. I’ll catch you,’ he had laughed. A test of trust: at least that was what Erlan thought it was. He had jumped. His father stepped aside. The rock did the rest. No test then, just a lesson: that you can’t trust anyone in this world, least of all the ones you love. Aye, he had learned that lesson well. That was why his father, his home, his inheritance – his very name – were all buried under an oath. Buried with her.

Because of his father’s lie, she had had to die. Inga – his first love. Inga – the ghost in his soul. She had cut her own throat and with the same stroke cut him loose from all that he knew and loved. So he was here, and she was there, lying under some barrow in the land of his birth. A land he had sworn never to see again.

He spat into the dust, as if that could expel the bitterness that rankled in his blood. Here, he was an exile. An outlander. Yet this was where he had found a new home and a new life after that other life had ended.

A cuckoo’s call floated down out of the treetops of the Kingswood.

He sighed, shaking off worn, old thoughts. Surely even a cripple couldn’t feel bitter on an evening like this? After the long winter the beech trees were in full garb, bulging in on the Uppland halls while the last of the sun splintered through their branches. His nostrils filled with the scent of the woods and meadows. Laughter and shrill voices tinkled on the twilit air as mothers called their children home. And with the dusk-dew, a kind of peace settled over the shingled roofs around Uppsala.

Maybe this was enough. Maybe this was his reward after enduring that dark and savage winter. He had arrived no better than a beggar, but King Sviggar had accepted his oath in return for salt and hearth. And afterwards came those mysterious deaths. Sviggar’s daughter, Lilla, had disappeared. Erlan had stepped forward. He had followed the trail into a vast, cold wilderness until it led him down into the dark depths under the earth. He entered seeking death. Instead he found life, and her. And he was a different man when he restored her to her father. The grateful king had honoured him, given him gold and a place on his council, even given him a new name: Aurvandil. It meant ‘shining wanderer’. But for now he had no need to wander.

Now? Why not for ever?

He crossed the expansive yard of the Great Hall. All was quiet. Most folk would be settling down to supper around one of the many hearth-fires. His belly grumbled in anticipation, hoping Kai had cooked something good.

Kai Askarsson was his servant, at least in name. Erlan had rescued Kai from a whipping post in a lonely corner of Gotarland, many leagues to the south. At the time it had been against his better judgement to let Kai tag along, but since then the Norns – those ancient spinners of fate – had woven together their paths tighter than the great wolf Fenrir’s leash.

Kai was fearless, reckless, irreverent, irrepressible, mischievous, garrulous, sneaky and downright mad at times. In short, about as different from Erlan as a man could be. But Erlan liked him better than any other, too.

He set off down the slope towards the scattered halls and houses that lay to the east of the Great Hall, eager to discover what Kai would conjure from their pot tonight.

That was when he heard a strange noise.

It stopped him at once.

He turned and shaded his eyes against the sunset, judging the sound to have come from back towards the Sacred Grove. Seeing nothing, he was about to shrug it away, when out of the haze emerged the silhouette of a horse and its rider. Even from there, he could see the rider was slumped over the horse’s withers.

There was another sound, halfway between a strangled salutation and a wail.

‘You all right there, friend?’ he called as the horseman drew closer.

No answer. And the horse kept on, so that Erlan was forced to lurch aside. Before he had time to object, the rider had collapsed on top of him.

They hit the ground hard, Erlan winded under the man’s full weight. The rider was groaning like a stuck boar. He was wounded, clearly, but only when Erlan slithered out from under him and saw his own tunic soaked with blood did he realize how badly.

He rolled him onto his back. ‘We need help here, now!’ he yelled. A stable-thrall appeared from under a byre and came running. Then a woman in a head-cloth emerged from a smithy. When she saw the blood-soaked rider she screamed. That brought others.

The man’s breath was grating like a saw. Erlan smelled the stink of punctured bowels and peered at his wound. It was an ugly gash caked black around its edges. Blood still welled from inside. His cheeks were deathly pale. Still, his face was familiar. Another of the king’s house-karls, Erlan thought, named Uttgar or Ottar, maybe? There were so many of the buggers it was impossible to remember all their names. ‘He needs water.’

The stable-hand rose and pushed through the gathering crowd. Meanwhile the rider was gulping at the air, bleeding.

Dying.

More folk were arriving, crowding round. ‘Give him some room, damn you!’ Erlan shifted, trying to cradle the karl’s head in his lap.

‘That’s Ormarr,’ said a thrall-girl.

‘Poor bastard,’ said a smith. ‘Look, he’s trying to say something.’

Certainly his lips were moving. Erlan put his ear to the tremulous breath.

‘The... Kolmark.’ Hardly a whisper.

‘The forest?’

‘Slain... all of us, slain.’

‘What’s he saying?’ the thrall-girl demanded, plucking at Erlan’s elbow.

‘If you shut up, I could tell you... Go on.’

‘War—tooth... War— tooth...’

‘Wartooth, he says. He must mean King Harald!’ declared the smith, who was leaning over Erlan’s shoulder. The name buzzed around the gathering. None was more hated or feared in all of Sveäland than Harald Wartooth, King of the Danes.

‘What’s the old bastard done now?’ growled someone further back.

Ormarr groaned.

‘He’s dying,’ the smith said, prodding a bony finger in Erlan’s ribs. ‘Ask him again.’

‘Look at me.’ He tried to brush Ormarr’s sweat-slicked hair out of his eyes. ‘What about the Wartooth? Who is slain? Speak, man.’ But the karl only rolled his eyes. ‘Where’s that bloody water?’ Erlan yelled, looking round for the errant stable-thrall. The nearest water butt was not thirty yards away but there was no sign of the fool. Not that a gulp of water would do much good now.

With a sudden surge of strength, Ormarr seized Erlan’s tunic and pulled him close. His eyes were burning with fever. He put his lips to Erlan’s ear and uttered his last words, so faint Erlan could barely hear them. Then his grip slackened, his eyelids drooped, his head fell back. Dead.

Erlan slumped back on his heels.

‘What ’e say?’ asked the smith.

But Erlan was staring at Ormarr’s lifeless lips.

‘He whispered something. Was it about the Wartooth?’

‘What did he say, damn it?’ demanded another.

Erlan rose to his feet, glaring right through the wall of eager faces, deaf to their questions, his mind fixed on one object and one alone. He had to see the king.

Because war was coming.

CHAPTER TWO

Sviggar Ívarsson, King of the Sveärs, sat on his oak-hewn throne tugging at his grey and white beard, glowering like a dwarf who’d lost his gold.

Behind the old king hung dusty tapestries – some depicting great deeds of his war-mongering father, Ívar Wide-Realm; others, scenes from older sagas of heroes long dead or tales of the ancient gods who still haunted the reaches of the north. The hour was late, the air fragrant with the scent of pine resin burning in stone-dish lamps. Around the chamber shadows danced, leaping with each flicker of the torches on the walls.

‘Confused words from a dying man,’ said Sviggar at last. His voice, though hollowed by age, still carried the weight of authority. When he spoke, men listened, and obeyed. ‘A man says wild things at death’s threshold. His words tell us nothing.’

‘His words are clear enough,’ exclaimed his son Sigurd, rising from his seat. ‘And someone put a blade in his belly!’

‘Sit down!’ Sviggar hauled himself to his feet. He was tall still and once must have been an imposing figure. But age, ever the vanquisher of great men, had reduced his long limbs to brittle sticks.

With a scowl, his son flung himself back in his chair and went back to tugging at the corner of a dark eyebrow. Erlan had witnessed this cavilling between father and son a dozen times at least since his appointment to the king’s council. More often the older, wiser head had the right of it, but this time Erlan wasn’t so sure.

Upon hearing news of this strange death, Sviggar had summoned an immediate council. However, only five members of his Council of Nine could be found just then: his son Sigurd, the white-haired goði Vithar, a pair of earls – Bodvar and Huldir – and Erlan himself.

These five were arranged around the council table according to their rank. The guards had been dismissed, all except Gettir, the son of Earl Huldir, who hovered in attendance of his father. There was only one other, gliding back and forth behind the king’s throne like some beautiful spectre, caressing a wine cup in long, slender fingers.

Perhaps it was natural that Queen Saldas was there: she had been present when Erlan brought word to her husband. Erlan, however, wished she wasn’t. Of course, with her raven-black hair, the smooth fall of her robe over the curves of her body and those restless emerald eyes, she was a distraction to any man. But Erlan had more reason than other men to keep his mind from wandering.

At the great feast that winter there had been certain words exchanged. A certain look in those green eyes. Now Erlan knew only a fool would set about cuckolding a king. Of course, if the prize were tempting enough, a man might hazard it. Saldas was undoubtedly that – Sviggar afforded himself the best of all things and his second wife was no exception. But there was something dangerous about her, something Erlan didn’t trust. He had decided to give her a wide berth.

She was looking at him now, a faint crease at the corner of her mouth. He took a swig of ale to break her gaze and the almost-smile curdled into a sneer. She turned away. ‘The message may be unclear, my lord husband, but some things are fact. A man arrives. He is wounded. He utters the Wartooth’s name and the Kolmark forest. He says war is coming. And then he dies.’

‘Exactly!’ cried Sigurd. ‘It confirms the rumours we’ve heard all winter.’

‘Rumours are like clouds on the horizon,’ his father growled. ‘Not every one brings a storm.’

‘We’re not talking about a few drops of rain, are we? All over the southern marches, it’s the same. Merchants from the south say Skania and Gotarland are bristling with spears. Have I not been saying so for months?’

‘Aye. To anyone who would listen,’ Earl Bodvar observed drily. Earl Bodvar was a dry man, with a voice so hoarse he might have swallowed a horn full of dust.

‘Fine. Mock me, Bodvar,’ Sigurd replied indignantly, ‘but this proves me right. Why else would the Wartooth be gathering men if not to bring war on us?’

‘Harald Wartooth would never do that,’ said his father. ‘He knows it’s a war he could never win. He’s no fool. It’s been thirteen years since the last blood was spilled. What could he gain by bringing war now?’

‘Vengeance,’ snarled Earl Huldir ominously. ‘Vengeance is what he seeks. And it’s what I will have from him and his seed one day.’ No one needed reminding why. Earl Huldir’s face bore a terrible scar that fell from his hairline, slitting his eyebrow, blinding an eye and leaving a purple seam across his left cheek. ‘The Wartooth owes me one eye and two sons. I mean to have them all before I join my fathers at Odin’s table. If that day is drawing nearer, I say let it come.’

‘No one denies your grievances, Huldir,’ said Sviggar. ‘This feud has cost us all much.’ His gaze happened to fall on Erlan. ‘Well, most of us. But if Harald is looking for vengeance, my father is already dead.’

‘The blood feud is not over until all debts are paid,’ replied Huldir. ‘While any of your line still lives, so the feud lives.’

‘This I know well,’ murmured the king in a weary voice.

This wasn’t the first that Erlan had heard of the feud between the houses of these two great kings. Princess Lilla had told him of it once before. But he had had no cause to think any more of it until now.

‘I hate to see this noble brow so troubled,’ soothed Queen Saldas, laying a hand against Sviggar’s forehead. ‘This talk is idle until we know more. Let me consult Odin. He is the giver of wisdom.’ She gestured at the aged goði leaning on his crutch. ‘Vithar and I will make the necessary offerings. The Hanged Lord will show us the course we must take.’

‘No one can deny your sacrifices are effective, my lady,’ the white-haired goði croaked, with an obsequious bow.

Erlan recalled the nine corpses hanging from the Sacred Oak that winter, sparkling under their veil of hoarfrost, each face frozen, each more beautiful than the last. Such were the sacrifices Saldas was only too willing to make to win the gods’ favour.

‘No,’ Sviggar replied at length. ‘Not that way.’

‘If war is coming—’

‘Aye, if!’ the king shouted.

His outburst was followed by an awkward silence. It was Earl Bodvar who eventually broke it. ‘My lord, I have a suggestion which you may find more practicable.’

‘Go on.’

‘This Ormarr was part of a shieldband that was scouting the southern marches. They weren’t due to return for another five days, but we’ve heard nothing else from them. My guess is we won’t. Ormarr mentioned the Kolmark forest—’

‘You want to send another shieldband to investigate?’

‘It would seem an obvious measure.’

‘Except that our border through the Kolmark is fifty leagues long! If he came from there – and it’s possible he did not – then it could be almost anywhere. It might take a shieldband weeks to find anything.’

‘Send two, then,’ boomed Earl Huldir, standing and pulling his son out of the shadows. ‘Gettir and his brother can lead a band of my men to scout the southern boundary of our lands in Nairka. No one in the kingdom knows that part of the forest better than them.’

Gettir Huldirsson looked straight ahead, offering himself for the king’s inspection. He was a lean, dark lad of eighteen or so, not much younger than Erlan himself. And thanks to Kai’s talent for gossip, Erlan happened to know he wasn’t a man to steer clear of a fight. The king eyed him doubtfully. ‘He’s very young.’

‘So he is,’ conceded Huldir, ‘but he’s capable. And my men obey him and his brother as they would me.’

Sviggar looked unconvinced.

‘Surely it’s at least worth looking, my lord?’ Earl Bodvar suggested.

Sviggar scraped a bony finger down his cheek. ‘Very well. We will send two scouting parties. One by the western road through Nairka, the other through Sodermanland.’

‘Thank you, my lord,’ replied Bodvar. ‘Would it also be prudent to send word to the other earls to make ready to raise their levies? If the worst should prove true.’

‘Of course it would,’ said Sigurd excitedly. ‘We’re wasting precious time even now. We should summon the levies at once, Father.’

When Sviggar still hesitated, Earl Huldir lost patience. ‘Gods – what are we? Old women! We should be bringing war to the Wartooth and his lands, not sitting here like a flock of hens waiting for him to come to us!’

‘Silence!’ cried the king, smashing a bony fist on the arm of his chair, making it shudder. ‘You’re all in such a fine lather to throw yourselves into the abyss.’ His eyes ranged over his councillors, grey and sharp as a well-honed blade. ‘I’ve seen war. Seen death and an ocean of blood. Wasn’t half my life given over to it? And did it ever bring my people any good? Wasted lives and wasted silver. But I did my duty to my father, all the same. When he died, that was the end of it. Instead I’ve built something that will endure. I will do nothing to provoke another war and put my kingdom at risk!’

‘Do nothing and your precious kingdom may be taken from you all the same,’ answered Sigurd in a quiet but firm voice.

‘A man is dead,’ Bodvar interjected before Sviggar could unleash more invective on his son. ‘As Lord Sigurd said: someone killed him. Even if you want to avoid war, surely it’s unwise to make no preparations.’

The old king grunted, his brow twitching like scales in the balance. After a while, he shook his head. ‘No. I’ll not be goaded into fanning the flames of war, nor stir up needless panic among these halls. We will dispatch these two shieldbands and they will find out more. But,’ he added, fixing Huldir’s son with a hard gaze, ‘you will keep within our borders. I’ll not give the Wartooth and his sons any provocation for war. Do you understand?’

Gettir said nothing, only bowed his head obligingly.

‘Do—you—understand?’ the king repeated.

‘I do, my lord,’ Gettir murmured, a grin ghosting about his lips.

‘Good. Now – who shall lead this second shieldband?’

‘I will lead it,’ said Sigurd.

‘Out of the question.’

‘What? But why, Father?’ Sigurd was a man of twenty-eight winters. Just then he sounded like a little boy.

‘I’ve lost one heir. I’m not about to lose another.’ Sviggar’s firstborn Staffen had been murdered the previous autumn. It was common knowledge that Staffen had been the son Sviggar had wanted for his heir. And none knew it better than Sigurd.

‘You can’t keep me from—’

‘Enough,’ Sviggar interrupted, waving him down. Sigurd slouched back onto his seat.

‘I will go, lord,’ said Erlan, earning himself a hostile look from the prince.

‘You? Erlan Aurvandil.’ Sviggar eyed him up and down. ‘No. Your place is here, beside me.’

‘Ormarr delivered his message to me. Am I not responsible for finding out the truth of this?’

The queen appeared at her husband’s shoulder. ‘Perhaps it’s no accident that the dead man found the Aurvandil,’ she said in a soft voice, never taking her eyes off Erlan. ‘A man’s fate finds him out.’

The old king regarded his wife, smoothing down his beard with brittle fingers. ‘Hmm.’ He suddenly chuckled and lifted his wine cup to Erlan. ‘Very well. It seems the Norns point their finger at you once more, my young friend. I trust you’ll be as lucky as you proved the last time.’

Erlan bowed low.

Lucky? If I were lucky, I wouldn’t be here.

CHAPTER THREE

It was already far into the night by the time they were dismissed, though Erlan doubted any of them would sleep much. Sviggar, perhaps, least of all.

Outside, under the vastness of the northern sky, Earl Huldir pulled up with a curse. ‘The man’s a mule-headed old fool!’ His milky eye glared fiercely in the gloom.

‘He’s no fool,’ returned Bodvar. ‘He’s just a cooler head than you, old friend.’

‘His indecision will get us all killed – whether he wants the fight that’s coming or not.’

‘We don’t know what’s coming.’

‘Horseshit, Bodvar! This thing has to play out. The Wartooth knows it. So do you.’ He pressed a massive thumb into Bodvar’s chest. ‘And I for one intend to make that son of a bitch pay.’ He nodded grimly at his son. ‘We’ll be ready.’ With that he stomped off into the night, his son Gettir following at his shoulder.

‘You think he’s right?’ said Erlan, looking after them.

‘That’s what you’re going to find out.’ Bodvar laughed – a short, sharp bark. ‘Count yourself lucky. You’re young. You’re an outlander. You have no blood debts to pay.’

‘Not here, anyway,’ muttered Erlan.

‘H’m,’ grunted Bodvar. ‘Maybe. But Huldir there – he’s been carrying the weight of those dead sons half his life. A man gets sick of a weight like that.’

‘Are there many like him?’

‘What a question!’ exclaimed Bodvar. ‘Hel, do you even know what this is about?’

‘Some. The princess told me once. Something about a disagreement between the old King Ívar and his daughter.’

‘You could call it that. Sviggar’s father was a mean old wolf. They called him Ívar Wide-Realm because no man before him had ever ruled over a kingdom so vast. He stole the Sveär crown from the last of the Yngling kings. The few surviving nobles loyal to the Ynglings escaped west into Norway. So Ívar made his own earls and gave them land. My father was one of them. Anyhow, things settled down. But Ívar’s ambition wasn’t sated. He fancied himself a piece of Danmark too and figured a way to get it. By then, he had a daughter. A handsome creature, by all accounts—’

‘Autha?’

‘So you know her name, at least.’

Erlan shrugged.

‘Aye. She was handsome. And clever, too. Far cleverer than her father. Maybe too clever for her own good. She liked to make a fool of him, especially in front of his own household, thinking she could get away with it. But he held scores, did Ívar, even against his own kin, and he found a way to use Autha to get what he wanted and see her sorry for it.’

‘How?’

‘By marrying her to one of the sons of the King of Danmark. The wrong son, so Autha reckoned.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘This king had two sons – the older was called Rorik and his brother, Helgi. Rorik was set to succeed his father but he was ugly and awkward. His brother Helgi was silk-tongued and fair as Baldur. Naturally, Autha wanted to marry Helgi, but instead her father gave her to Rorik, who was soon wearing the Danish crown after his father died.’

‘So Autha became Queen of Danmark.’

‘Aye. But then Ívar starts his scheming. He sets rumours flying that his own daughter has been sharing Helgi’s bed. Of course, King Rorik doesn’t fancy that, so he has his brother murdered. There’s an outcry, and the accusation of Autha’s infidelity is there for all to see. And so, humiliated, Autha sends word to her father, begging him to avenge her honour – aye, and the man she truly loved. And old Ívar was only too happy to oblige. He sent an army south, routed the Danes and slew King Rorik.’ Bodvar gave a low chuckle. ‘It was only then that Autha realized her father had only ever meant to steal Danmark for himself and that she’d been used.’

‘What does any of this have to do with Sviggar?’

‘Sviggar was Ívar’s only other surviving child. Bastard-born, but still... He was a lad when all this caught fire. Autha rallied support to throw her father out of Danmark, but he soon defeated them and she fled with her own son, Harald.’

‘The Wartooth?’

‘Aye. The Wartooth.’ Bodvar grinned. ‘Keeping up?’

‘Just about.’

‘Good lad. Of course, Harald was just a boy then, too. Autha took him east, made alliances, raised an army. And Ívar couldn’t let it lie. He went in pursuit of her. The wars between them flared up now and then. Harald grew to manhood and took up his murdered father’s claim over Danmark. So it went on.’

‘Those were the Estland wars?’

‘Aye. Many of us cut our teeth there, myself included. And Sviggar... He made a name for himself over there. He was a Hel of a man to follow into Skogul’s Storm, I tell you...’ Bodvar looked up into the night, presumably recalling battles past. Suddenly his eyes snapped down. ‘Anyhow, by the end Autha claimed both Danmark and Sveäland as hers by right, saying no bastard-born son could deprive her of her inheritance. She died making her son Harald swear he would recover both. And then old Ívar died, too – drowned off the Estland coast.’

‘And that was the end of it?’

‘For a time. Harald Wartooth raced back to Danmark to secure his claim there, and Sviggar did the same here. That’s how things lay for a long while. Sviggar here in Uppsala, ruling the Sveärs and a few other tribes. Harald Wartooth, ruling Danmark and a few other lands from his hall at Leithra on the isle of Zealand. Neither was strong enough to uproot the other. Although they tried a few times.’ He winked. ‘Usually it was the Wartooth flexing his muscles.’ Bodvar nodded in the direction Earl Huldir had disappeared. ‘That’s when two of his sons were slain. Eastern Gotarland saw many battles but they only served to prolong the feud and deepen the debts of blood. So that’s how it stands. The Wartooth holds sway over the Eastern Gotars, from Skania in the south all the way north to the Kolmark.’

Erlan scratched at his scrub of a beard. ‘I guess that’s where I come in.’

‘I guess it is,’ said Bodvar, slapping him on the shoulder.

‘Think we’ll find anything?’

‘Who knows? The forest is vast and thick as the hair on a bear’s backside. But maybe the gods want to see this feud played out, like Huldir says.’

Erlan nodded. ‘And what about you?’

‘What about me?’

‘Don’t you have blood debts to settle?’

The lines of Bodvar’s craggy face cracked into a broad smile. ‘I have no brothers, no sons. Only daughters. Three of them, and a giant thorn in my arse they are too. But at least they’re alive.’

Erlan laughed.

‘Well, my friend, I’m to bed. Meet me here tomorrow at the Day-Mark and I’ll pick you a good crew. Something tells me you’re going to need it.’

A short walk later Erlan was pushing aside the hide-skin drapes that kept the heat inside the house where he lived with Kai. It stood among the smaller barns and dwellings that lay to the east of the Great Hall. A modest place, with a turf roof and strong timber walls – easy to keep warm if there was a chill in the air.

Erlan slept on the bench near the hearth-fire, but Kai preferred the loft, apparently unfussed by the smoke that gathered in the rafters before it found its way out of the smoke-hole. He maintained anything was better than sleeping near Erlan, who, he claimed, snuffled like a boar digging for acorns all night long. Of course, Erlan denied it.

He shuffled inside and let the drape fall.

‘Frey’s fat cock,’ exclaimed Kai in a loud voice. ‘You took your sweet time!’

‘Aren’t you asleep yet?’

‘How am I supposed to sleep after the hornet’s nest you’ve kicked over?’ A mess of blond hair appeared over the edge of the hayloft. Kai pushed his fringe out of his eyes and swung his legs onto the ladder. ‘What’s it to be, then? A spear for every man, set sail for Danmark and bugger the consequences?’

‘Not exactly.’ Erlan slumped on the sheepskin that lay along the bench and began pulling off his shoes. ‘I’m to lead a shieldband into the Kolmark and see what I can find out.’ He leaned back and set about kneading the soreness out of his aching ankle.

‘What’s to find out? It’s war, ain’t it? The whole place is saying so.’

‘Well, they can unsay so. Sviggar’ll cut the tongue out of anyone who goes spreading talk like that. Not till we know more.’

‘The Old Goat’s a bit late for that! He might as well try and push a fart back up the Fat-Belly’s arse. They’re damned windy these Sveärs, you know.’ Being Gotar-born himself, Kai was happy to cast aspersions. ‘They’re all croaking away like a sack of frogs.’

‘They might have good cause to croak. We’ll know soon enough.’

‘By the way – there’s ale in the jug if you want it.’ Kai jerked his head at the smoke-stained pot hanging over the embers in the hearth. Erlan grabbed an ox-horn mug and ladled some out. Meanwhile, Kai had shinned down his ladder and begun rummaging about under the loft.

‘What the Hel are you doing?’

‘What do you think? Sorting my gear. I suppose we’re riding out early, eh?’

Erlan realised he should have anticipated this. He sighed. ‘No. I ride out. You’re not going anywhere.’

‘What? Why not?’

‘Because...’

‘Well?’

‘Because I say so. You’re not fully trained yet.’

‘Not fully trained! Then what the Hel have we been doing all these months?’

‘Look, if something happens, I don’t want to be worrying that some oversized Danish troll is about to knock that empty head off your shoulders.’

‘You do talk horseshit sometimes, master. Have you forgotten last winter – when the Vandrung came? I killed as many of those things as any of us. And two wolves ’n all!’

‘That was different. We had no choice.’

‘You’ve got no choice now, either. Need I remind you that we’re blood-sworn, you and I?’ Kai pulled up his sleeve to show off the thin scarlet seam across his forearm where he’d cut himself and made his oath. A gesture he used to dramatic effect about five times a day. ‘Where you go, I go.’ He gave a nod, as if that was an end to it.

‘Not a chance. Next time... maybe.’ Erlan smiled and got a scowl for his pains. ‘Anyhow, the whole thing could be a fool’s errand.’

‘You don’t believe that. And you know I’m worth five of any of those halfwit karls that’ll ride with you.’

‘You’re worth fifty,’ snapped Erlan, losing patience. ‘That’s why you’re staying here.’ Kai frowned, unsure of the comeback to that. ‘Listen, you mad little bastard. If there is a war coming I promise you aren’t going to miss out. This way at least I’ll have time to finish your training. The shieldwall is savage. Others can fall cheaply if that’s their fate, but I’m going to make damn sure you aren’t one of them.’

Kai slouched onto the bench and helped himself to a mug of ale. He gazed dejectedly into the amber liquid. ‘Bara says, till I’ve proved myself as one of the king’s hearthmen, I don’t stand a chance. Those were her exact words.’

Erlan burst out laughing. ‘Is that all this is about? Bedding Bara?’

‘What do you mean, all? That’s about the best reason there is!’

These days it seemed whatever the starting point, their talk always led back to Bara. To say Kai was besotted was a blistering understatement. And if the servant-girl had been elusive before, since she had been appointed handmaiden to the queen she had made it very clear that she was now utterly beyond Kai’s reach. Elfin pretty, fire-headed, fire-tempered, lissome as a wildcat, conceited as the day was long, she was no easy tree to fell. And by the gods, Kai had put in some axe-work.

‘Well, here’s to the chance to prove yourself.’ Erlan raised his cup. ‘Might be that day’s coming sooner than you think.’

‘No thanks to you.’

Erlan shrugged and drank anyway. Eventually, moodily, Kai joined him.

‘You’re sure I can’t tag along?’

‘Next time.’

‘Piss on it then! And piss on you!’ Kai stormed off to his ladder. ‘Still,’ he added on his way up it, ‘there’s many a rung in war for a man to climb to higher stations in life.’

‘For a resourceful fellow like you – no doubt.’

‘Exactly! And you too, master. I mean, this place is all well and good but we hardly want to live here for ever. You being destined for great things and all!’

‘Great things?’

‘Undoubtedly, master. And Kai Askarsson is going to see that you get ’em.’

‘What kind of things?’

‘Land. Silver. A buxom wife. Four square walls, and big ones too. Oh, I’ve got plans for us. Don’t worry about that. It’s all in hand.’

Erlan heard Kai settle into his nest of straw and blankets. ‘You dream on, my friend,’ he called up. ‘I’m going for a leak.’

Is that what war will bring? he wondered, as he unlaced his breeches outside. Land and wealth and fame. The love of his lord and king.

No. War might bring him a lot of things. But it couldn’t bring him the one thing he wanted.

Because no matter how many men you kill, you can’t unstitch the past.

CHAPTER FOUR

Princess Aslíf Sviggarsdóttir swept towards the queen’s chamber with the ease of one long familiar with the blackened sconces on the wall, the shuffle of rushes underfoot, that rugged smell of ageing oak in her nostrils.

Her earliest memories whispered like ghosts in these shadows, when it was her own mother she rushed to see, her own childish squeals of delight as she was swept up and swung around in those comforting arms. That was long ago. She remembered how her mother would whisper her name close to her ear like a secret. ‘My little Lilla. My little Lilla.’

‘Lilla’ was the nickname her brother Staffen had given her. It meant simply ‘purple’ – chosen, he said, because her legs were always turning that colour when she was a baby. But like all silly names, it had stuck. She didn’t mind. She preferred it to Aslíf anyway.

But now her mother was gone and the chamber belonged to another. To this Saldas, her father’s second wife of four years past. And instead of her own infant footsteps, it was those of Saldas’s children that rattled the floorboards beside her.

Every day she would bring her half-brother and half-sister to the queen’s chamber to say ‘good day’ to their mother. Afterwards she would take them to the Kingswood where they helped her find herbs and seeds, and she would teach them about the flowers and plants that grew there and the healing lore that her mother once taught her.

But today was different. Today her steps were urgent as she half-dragged the children along the corridor by their little fists. Because yesterday the halls had been turned upside down. Someone who had watched that poor man die had told her maidservant what had happened. It sounded grim, and grimmer still the words of foreboding the man had spoken.

As soon as she heard it, Lilla had dressed and sought out her father, only to discover he was already in council. There he had remained. The night had worn on until Lilla grew weary of waiting and had retired to her bed where she had been troubled by a swirl of dreams. Somewhere within them, she had seen that dark place again, and shivered with the memory of the cold. And afterwards another dream, in which she saw a wolf snarling at a wolfhound, ready to fight. The hound had only one eye and seemed from its movements to be lame. But it was fearless and stood its ground, unafraid of the wolf with its fierce fangs. Before they fought, her mind had drifted on. Several times she had seen Erlan’s face as it had been in that dark place, filthy, gaunt, urging her onward, mouthing something, some warning perhaps. Only when she awoke did she wonder whether the lame dog was connected with him. If so, it was a strange image indeed.

While she had passed a fitful night, she knew her stepmother had been admitted to the council. That was why she hurried. Saldas would be able to tell her all that had been said.

‘Good day, Mother,’ she called through the curtain. Mother. The word was a joke. Saldas was hardly ten summers older than her – but she insisted Lilla use it. ‘May we come in?’

‘Enter,’ came the reply, in a low, melodious voice. Lilla pushed aside the drape and hustled in the children.

Saldas was seated before the tall mirror propped against the wall, its silver surface polished to a shine. She was wearing a flowing white robe and, unusually, was combing out her long black hair herself. She rose to greet them.

There was the usual awkwardness as first Svein and then Katla embraced their mother. For all the queen’s grace, Lilla had never seen a mother less natural in handling her own offspring. She kissed each child in turn, smiling – though her eyes stayed cool.

‘You slept well?’ asked Saldas.

Svein was already busy pulling out a chest from the corner and began unpacking his collection of wooden toys in front of his little sister.

‘Not really. I don’t suppose many did.’

‘A little soon to be losing sleep, I think,’ Saldas said with a note of contempt. She wafted a hand at the edge of her bed.

Lilla took the seat, glimpsing a flash of honey-blonde hair above the pale russet of her dress as she passed the mirror. ‘Are you not anxious about what is to come?’

‘Why fear the future?’ Saldas smiled mysteriously. ‘Better to control it.’

How could one control the future? Lilla wondered. Especially in war. ‘I suppose the Norns weave all of our paths.’

The bridge of Saldas’s nose wrinkled. ‘An obvious thing to say, my daughter. I should have thought better of you.’ She chuckled as though it were a shared joke, but the condescension in her eyes nettled Lilla. ‘I prefer to weave my own,’ Saldas added. ‘Anyway, we know next to nothing about this supposed threat. And your father seems reluctant to learn more.’

‘Something must have been decided. The council talked until late.’

‘You know how it is with men, my dear. Each one must be heard five times over and none is ever persuaded. So round it goes.’

‘Father must have settled on doing something. His folk need reassurance at the least. I should speak with him. Perhaps there’s something I can do.’

‘I fear not. The best you can do is make sure this beautiful face keeps its composure.’ Saldas stroked a fingertip down Lilla’s cheek. ‘So lovely...’ She sighed. ‘If you must know, your father has sent two patrols south. They may find something.’

‘Who is to lead them?’

‘Gettir Huldirsson leads one. And the other is—’

‘Erlan,’ Lilla said without thinking.

‘Why, yes! How did you know?’

‘I didn’t,’ said Lilla, although she must have. She thought of the dream and her belly tightened.

‘Hmm. A premonition then,’ Saldas replied casually, inspecting some detail in the mirror a little closer, flicking at her hair with her comb. When she looked up, her expression changed. ‘Why, my dear, you’ve gone quite pale. Are you unwell?’

‘No. I— I’m fine.’

‘Ah.’ The queen’s frown slid into a knowing smile. ‘I see. You hold a secret affection for him.’

‘No! I—’

‘It would only be natural after all he did for you. But you mustn’t fret on his account. He’s a most able young man. Despite his... affliction.’

‘It’s not that. I just...’ Lilla trailed off, feeling miserably transparent. ‘When do they leave?’

‘This morning, I think. Perhaps they’ve left already.’

Lilla was on her feet immediately. But then she stopped. Now it was her being awkward. She felt her cheeks burning. Her eyes flicked between the door and the children, caught between staying and going.

‘Go on,’ said Saldas languidly, turning back to her reflection. ‘Though I fear you may be too late—’

Lilla didn’t wait to hear more. She was at the door and through the drapes, hurrying along the corridor and outside into the crisp morning air. She felt stupid. She hated her stepmother to see more than she meant to show her, and she had let her guard down. In truth, her reaction was a surprise even to herself. But she couldn’t think about that now. It was more important to see him if she could.

The day had started brightly, but there was a thin skein of cloud forming high above. Once the sun climbed up there, it would be a dull day and already, as she hurried towards the scattered dwellings to the east, she felt the coming gloom infecting the folk that she passed.

She had no idea what she wanted to say to him, but the threat of war seemed to lend urgency. Instinct told her she must see him. But why? She couldn’t say.

Maybe Saldas was right. Maybe it was only natural that she should fear for him. After the dark terrors of that winter he had been much in her mind. Only he understood what she had endured. Only he had followed her down into the dark heart of the earth where they had carried her, only he had seen those terrible things that still filled her mind with horror.

The memory of it all was more like a nightmare than something real. Those fearful creatures that had snatched her from the Kingswood, dragging her a hundred leagues or more across a snowbound wilderness, and then plunging her deep down under the earth. She had thought herself lost for ever... until she saw his face. Somehow he had come for her. Somehow he had got her out. They had got each other out, for she had killed too. And they had escaped to the light, no longer the same people.

How could they be after that?

But there was something else that drew her to him. He was an outsider like her. He had come to her father’s hall in bonds, together with that odd friend of his. He had been a stranger with a clumsy way of speaking. Yet surely some favourable wind of fate blew at his back. From a beggar’s rags, he had risen to the high council. More, her father now saw him almost as a favourite.

She passed a smith’s forge and caught snatches of talk from some hall-folk gathered there. Words like blood, steel, slaughter. It would be the same all over Uppsala. Words uttered like poisonous invocations, their dark magic summoning death ever closer. She glimpsed the grindstone whirring, sparks flying. Already men were sharpening their killing edges.

So it had begun. And what could she do to stop it?

She hurried on, her thoughts returning to Erlan.

The king’s favourite... Her father’s last favourite, Finn Lodarsson, had met with a bitter end, murdered in her father’s mead-hall in plain sight of everyone. He had died choking, death gurgling in his throat.

A horrible sight.

Traces of wolfsbane were found in his cup. Suspicion fell first on one man, then another. Men were tortured. But nothing came of it. No motive. No reason. Only silence, until eventually folk stopped talking of it. Or if they did, they began to doubt Finn was murdered at all. Just one of those things, they said. He was ill-fated.

Aye, thought Lilla. In the end, fate is guilty of all things.

She stopped. There in front of her was Erlan’s squat little home. She was breathless from her hurrying and, she realized, probably flushed too. She felt foolish. She took a moment to straighten the brooches pinning her robe and apron, then smoothed out the strings of amber beads hanging between them, pushed the wayward strands of hair behind her ears and re-tied the ribbon at the nape of her neck. All of a sudden the door flew open and a warrior, looking like Tyr himself, stepped outside.

He was so wrapped in gear, it was a moment before she recognized him. His helm hid his tousled black hair, but the dark grey eyes shining out either side of a long nose-guard were unmistakably his. Over his tunic he had a leather byrnie crossed with belts and slings supporting a small armoury: a hand-axe, a couple of seax fighting knives, a limewood shield slung over his back and of course his precious ring-sword, sheathed in an ox-hide scabbard, at his hip.

She realized she was staring and looked away.

‘What are you doing here?’ he said.

She opened her mouth but just then Kai appeared, carrying a cloak and a sort of knapsack, presumably his master’s.

‘Lady Lilla!’ he exclaimed. ‘A fine day for a ride, don’t you think?’

She looked up, as if noticing the sky for the first time. ‘I fear it won’t last,’ she replied distractedly. She turned to Erlan. ‘I need to speak with you.’

‘They’ll be waiting for—’

‘Alone.’

Erlan shrugged in acquiescence and sent Kai off to fetch his horse, sniggering. ‘So...?’

‘I had a dream about you.’

‘A dream? I’m flattered.’

‘You were in danger.’

‘Well, all of us may be in danger.’

‘This was different.’

‘How?’

‘I don’t know exactly.’ She described her dream to him, the wolf and the wolfhound. He listened carefully.

‘That could be anyone,’ he said when she had finished. ‘But I kept seeing your face in those black caverns. And there was another.’

‘The Witch King?’

‘No.’

‘Who?’

‘I— I couldn’t make it out.’

A shadow fell across his face. ‘Those were dark things, Lilla. They’re best forgotten.’

‘How can I forget?’ she exclaimed. ‘How can you?’

‘Listen, Lilla. I’m sorry. I can’t help every dream you have.’

‘But don’t you see? After what we went through... We’re... connected. After what we endured together.’

‘Are we?’ he said coldly. ‘Granted, we both endured. We both lived. But that’s all. You’re the daughter of a king. And me...’ He shook his head.

‘You’re wrong, Erlan. The dream means something. It was a warning.’

‘A warning? Of what?’

‘I can’t say. Please, Erlan – I need you to be careful.’

‘What need have you! Your father has a hundred other men here to protect you. He could call upon a thousand more. Why do you care what happens to me?’

‘I don’t know.’ She looked up at him and saw his dark eyes soften a little. ‘I do, though.’

‘Fine. I’ll be careful. But if we run into the Wartooth’s men—’

‘It’s not the Wartooth that I saw.’ She seized his hand. ‘Promise me you’ll be vigilant.’ He said nothing. She squeezed his hand tighter. ‘Promise me.’

‘All right... I promise.’

She smiled but he was looking over her shoulder. Kai had returned with one of the large scout-horses from her father’s stable. ‘The gods go with you,’ she said, and stretched up to brush her lips against his cheek. She felt him start, but before he could answer, she was already hurrying away up the hill, the imprint of his stubble prickling her skin.

CHAPTER FIVE

It was nearly noon by the time they rode away. The crowd of onlookers parted like a bow-wave as they took the road east.

Most of the horses were strong and fit although Erlan had his doubts how Einar Fat-Belly’s mount would fare. Gloinn was another, with limbs so long that, sat on his horse, he looked like a spider riding a woodlouse. The rest of them were a decent enough crew. Jovard he trusted, having fought with him before. Jari Iron-Tongue was a beefy lad, useful in the training circle, but never seemed to give his mouth a rest.

He was less sure of some of the others. Aleif Red-Cheeks was a churlish bastard at the best of times, and argumentative too, with a face full of sores. He had taken an instant dislike to Kai when they arrived in Uppsala and he wasn’t too keen on Erlan, either. The feeling was mutual. His friend Torlak the Hunstman was another Erlan might have done without, but the choosing had been Earl Bodvar’s. He had assured Erlan that Torlak was one of the best trackers in Sveäland and a useful man to have on your elbow if things got savage. Erlan trusted Bodvar’s judgement. Then again, he didn’t have much choice.

There were others – Eirik Hammer and a couple more. Ten in all, and they had a fair distance to go. It would take them the better part of two days’ hard riding, heading first south-east towards the ferry crossing at the neck of the Great Bay. On the south side, they would cut south-west across the Earl of Sodermanland’s estates until they came to the northern edge of the Kolmark forest. There, the road turned south, driving straight as an arrow through the forest until it reappeared in Eastern Gotarland, the northernmost territory under King Harald Wartooth’s rule.

But all this lay far ahead.

The men were in high spirits. It was a pleasant enough day and what wind there was had swung round to their backs. Erlan relaxed his reins, letting his horse find a rhythm it could sustain for most of the day.

Ten men. Either this was a waste of ten men’s time, or else... Would ten be enough?

He shelved his doubts. He was glad to be going. This mystery had landed in his lap – literally – and he could at least admit to himself that he was curious to know the truth of it.

The road skirted the southern edge of the Kingswood. The lead riders had just reached the place where the road split from the trees when two horsemen suddenly appeared and stopped beside the track.

Erlan called a halt.

‘Good day, Erlan Aurvandil!’

‘Lord Sigurd,’ returned Erlan, warily.

On the second horse sat the prince’s oathman. ‘Vargalf,’ nodded Erlan. The servant’s gaunt features flickered, apparently all Erlan would get for a greeting. The pair were in full war-rig, leather greaves on their forearms, shields on their back and twin-ringed swords at their hips. Erlan noticed a ring-mail shirt rolled up behind Sigurd’s saddle. An expensive item, and heavy too. Not something to carry about without good reason. ‘Come to wish us good fortune, my lord? I’m flattered.’

‘Don’t tell me you’ve developed a sense of humour, cripple.’

There were a couple of laughs behind him, but Erlan didn’t care. He had heard that taunt all his life. ‘Is there something you want to say then, my lord? Or are you going to stand there blushing like a maiden on her first night?’

The smirk fell from Sigurd’s face. ‘We ride with you. No questions.’