Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Wanderer Chronicles

- Sprache: Englisch

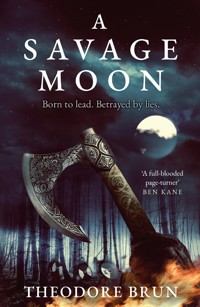

'A full-blooded page-turner' Ben Kane An epic, spellbinding Viking fantasy of blood and battle, weaving together history, fantasy and ancient myth. Perfect for fans of The Northman and Game of Thrones. Byzantium, 718AD The great siege is over. Crippled warrior, Erlan Aurvandil, is weary of war. But he must rally his strength to lead a band of misfit adventurers back to the North, to reclaim the stolen kingdom of his lover, Lilla Sviggarsdottir. For this, they need an army. To raise an army, they need gold. Together they plot a daring heist to steal the Emperor's tribute to his ally. Barely escaping with their lives, they voyage north, ready for the fight. But when fate strands them in a foreign land already riven by war, Erlan and Lilla are drawn inexorably into the web of a dark and gruesome cult. As blades fall and shadows close in, only one thing for them is certain: a savage moon is rising. And it demands an ocean of blood. Praise for Theodore Brun: 'A masterly debut... If Bernard Cornwell and George R.R. Martin had a lovechild, it would look like A Mighty Dawn. I devoured it late into the night, and eagerly await the sequel'THE TIMES 'Gripping. Gut-wrenching' ERIC SCHUMACHER 'Superb historical fiction' GILES KRISTIAN

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 721

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Theodore Brun studied Dark Age archaeology at Cambridge. In 2010, he quit his job as an arbitration lawyer in Hong Kong and cycled 10,000 miles across Asia and Europe to his home in Norfolk. A Savage Moon is his fourth novel.

Also by Theodore Brun

A Mighty Dawn

A Sacred Storm

A Burning Sea

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Corvus

Copyright © Theodore Brun, 2023

The moral right of Theodore Brun to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 614 0

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my old friend Will.

The light shines in the darkness. And you were first to point me towards it.

Thence come the maidens mighty in wisdom, Three from the dwelling down ‘neath the tree; Urth is one named, Verthandi the next, – On the wood they scored, – and Skuld the third. Laws they made there, and life allotted To the sons of men, and set their fates.

From ‘Völuspá’, Stanza 20.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

IN THE CITY OF BYZANTIUM:

Erlan Aurvandil – the ‘Shining Wanderer’, a crippled warrior of the north, lately in service to the Byzantine Emperor.

Lilla Sviggarsdottír – the exiled Queen of the Twin Kingdoms, a Sveär by blood, and only surviving kin of Sviggar Ívarsson, the murdered King of Sveäland.

Emperor Leo III, the Isaurian – Basileus of the Byzantines and victor of the Great Arab Siege of Byzantium.

General Arbasdos – Strategos of the Armeniac Theme and kouropalatēs, the second most powerful man in the empire and Leo’s personal ally, who once held the Wanderer as a slave.

Princess Anna – the Basilopoúla, oldest child of Emperor Leo, and young wife of General Arbasdos.

Einar the Fat-Bellied – Erlan’s comrade in arms, a Sveär still loyal to the kin of Sviggar the Bastard.

Orīana – an actress and star of the Hippodrome, and Einar’s lover.

Marta – her daughter, a novice nun.

THE REMNANT CREW OF THE FASOLT:

Demetrios – a Greek helmsman, who joined them in Varna.

Mikkel Crow – an Estlander river-man.

Snodin – de facto skipper during the Arab siege, also an Estlander.

Ran – a Gotlander.

Black Svali – an Estlander shipwright.

Vili, known as ‘Bull’ – the youngest and biggest of the Estlanders.

Dreng, Krok & Kunrith – their crew mates.

IN THE CITY OF ROME:

Katāros – the disgraced High Chamberlain of the Imperial Palace or parakoimo-menos. A eunuch of northern origin and traitor to the empire.

Dom Vittorio Massimo – a judge of the city.

Antoninus – Dom Massimo’s personal secretary.

Justus – steward of the Palazzo Massimo.

Emilius – a merchant.

Peter, Duke of Rome – the chief administrator of the city.

Brother Narduin – a Frankish pilgrim.

IN THE KINGDOM OF THE FRANKS:

Karil Martel – Duke (dux) of Austrasia, eldest surviving son of Pepin of Herstal and leader of the Austrasian nobles against the Merovingian king, Chilperic. Later known as ‘the Hammer’.

Childebrand – a Frankish nobleman, illegitimate son of Pepin of Herstal and brother of Duke Karil.

Wynfred of Nursling – an Anglo-Saxon missionary. Known as ‘Wyn’.

Berengar, son of Berulf – a Frankish trapper.

Alvarik the One Eyed – a shaman and leader of the cult of Báleygr – ‘the Flaming Eye’.

Fenna – a Frisian girl.

PART ONE

URðR

THE THREADS OF WHAT WAS

CHAPTER ONE

She smells pine needles, and death.

The sweet, damp scent of the forest litter. A scent so unmistakably of the north that she knows she must be dreaming. She feels the warm earth beneath her feet, its touch familiar to her as her father’s embrace. Even in the dream, her heart aches with a sudden pang of longing.

For home.

So far away. And yet, in the dream, near as her hands and feet.

There has been rain not long past. And now she sees the pines around her, their branches close enough to reach up and touch. Droplets of water still cling to the tip of each needle. She brushes them, her fingertips scattering tiny jewels of light to the ground. There is no hurry. She is at peace. As she always has been in the Kingswood, close to her father’s hall.

The hall that was torn from my grasp.

This thought enters her mind like a splinter. But the forest air is still. Her footsteps tread softly in the earth. The light is dim, though she cannot tell whether it’s the gloaming of dusk or else the grey before the dawn. She glances up again and the tops of the trees now seem far away. Far as the great vaulted dome of the Holy Wisdom. Far as the heavens. Yet dark as them, too.

No light penetrates their branches, only shadows seeping through like a mist, filtering down to her from on high.

Now that other smell grows stronger. Sickly sweet, like rancid meat.

She is following a trail through bracken. A deer trail, maybe. There were often deer in the Kingswood. Some animal has been this way, anyway. She knows this place, knows where it leads. To the Great Ash. To her ash. The one tree in all her father’s kingdom which, as a girl, she could make believe might be Yggdrasil itself – the ancient World-Ash and the bridge between the world of men and many others. Later, when a woman grown, she went there to breathe in the smoke of Urtha’s Weed, thinking herself wise, and skilled enough to journey between them, like a vala of the Old Times. Now she knows better. Now she is wise enough only to know her own ignorance.

The smell of death becomes a stench. She covers her mouth. A low hum invades the silence, dull at first but growing louder, and louder still, till the sound fills her ears. Fills her skull. Flies buzzing. Hundreds of them, thousands. All come for a feast, swirling about her head like the sands of some desert storm in a spice-merchant’s tale.

Then she sees it – a great hulking shadow in the dismal gloom. A monstrous beast, its outline blurred in the hungering dark, a huge muscular back, spiked with hair stiff as thorns, head bent low to some busy work. A boar, she now sees, and over the buzzing of the flies she hears a repulsive, eager gulping as the boar scarfs down… something.

She cannot make out what.

She circles the clearing until, through the swarming flies, she is able to spy what the boar feasts upon. Another creature of the forest. A large grey wolf stretched out under the boar, its lifeless limbs jerking with each thrust of the brutish snout as the boar burrows hungrily into its innards.

She halts, revolted, yet gripped by the weirdness of the scene. She wants to turn away but cannot. And as she looks, the vision becomes stranger still. The shape of the wolf corpse begins to change, like a long, lean sculpture of wax, melting away, resolving into something new. Now she could not have torn away her gaze though her life were the forfeit.

For where before she saw a wolf lies now the wasted body of a man. Naked, limbs withered, face gaunt. And worse, a face she knows. The long black and grey hair, the blunt edge of the jaw, the strong crooked nose.

Father.

The word ghosts over her lips as the boar gives the corpse another shunt. His head flops over, his dead eyes fix on her. Calling to her. Accusing her…

Where are you, my daughter?

She recoils, her belly filling with horror. A stick snaps underfoot. The boar lifts its head. For a long moment, they regard one another – woman and beast – the air between them filled with the boar’s grating pants, the coarse bristles of its snout glistening with her father’s blood. And as she looks, the animal’s long, thin lips curl into a sneer, moving as though in human speech, a whisper in her ear:

Whatever you have, I will take from you…

Queen Lilla Sviggarsdottír sat up suddenly, pulse thudding in her temple. Her long hair hung like a funeral veil over her eyes, dishevelled and clammy with sweat.

For a few seconds she stared wildly through the tangle of honey-gold strands, panting as if she’d run a league, forcing herself to take in the pale cream curtains, the thick marble pillars flanking the muslin drape across the doorway, its folds riffling with the breeze off the Bosporus. She smelled cedarwood and cinnamon. And the scent of the man beside her.

‘Are you all right, my love?’ His voice cracked the darkness, his breath close to her cheek.

Erlan.

It didn’t seem long since that had been her question to ask of him – when the fever had had him in its grip. Are you all right? Which really meant: Are you still alive?

Too often, she had feared he was not.

She nodded at his shadow, unable to do more as the terror of her dream leached from her mind. This was her present, she told herself. This was her now. And yet she heard the echo of those words:

Whatever you have, I will take from you…

Words from her past. Words that the man who usurped her kingdom had hissed in her ear as he thrust her face down into the fresh earth of her husband’s grave.

She brushed aside her hair, sank back into the goose-down pillows and expelled a long sigh. ‘I’m… I’m fine.’

‘You were dreaming again.’ Erlan was propped on one elbow beside her, his dark eyes still luminous in the shadows of night, even though the sickness had stolen much of their lustre. He reached out and chased a last lock of hair from her face. ‘Was it the same?’

‘Yes. The boar… and my father.’

‘I’m sorry… that it troubles you so.’

‘Of course it troubles me,’ she answered quickly. ‘It’s four months since you told me it was time to go home.’ She sat up, drawing her knees to her chin under the silk coverlet. ‘Yet here we still are.’ She knew she sounded cold. She couldn’t help it. The well of her sympathy was deep. But even the deepest well could run dry.

‘I can’t help that I was sick—’

‘You know I don’t mean that.’ Still her tone was sharper than she intended. After all, Erlan had come within a blade’s edge of death. The wounds he had taken on that night of fire had festered. It had needed all the skill of the emperor’s best physicians to keep his feet from the Hel-road. Looking at his sunken eyes, his hollow cheeks, it was doubtful whether even now he was quite well. ‘I’m not blaming you. I just…’ She shook her head. ‘We must go back. I owe it to my father’s memory. And to the oath I swore to my husband.’

‘Your father’s memory has waited this long. Wherever he is, he can wait a little longer,’ he said, his voice a croak. ‘As for Ringast, you owe him nothing.’

She stared at him in the dark. ‘How can you – of all people – think so little of an oath?’ Gods, hadn’t he made her suffer for his own?

Erlan jerked upright, fully awake now. He reached across her to a cup and the pitcher of watered wine on the stand beside the bed. He poured it out, gulped down a couple of mouthfuls. ‘Oath or none, you heard what the emperor said. He has nothing to spare you. No gold, no men.’

The disappointment of her last audience with Emperor Leo still lingered, sour as rancid milk. Leo the Isaurian, third of his name, now hailed the Great Lion of the City. Saviour of the Faith, the Anointed of God. She frowned, remembering how her appeal had fallen on deaf ears. It is a time to rebuild, Leo had said. For the city to breathe. And you, too, my lady. Wait till the spring… then we will talk again.

‘We still have the crew,’ she said, fumbling for some thread that would still hold. ‘And the Fasolt, thank the gods.’ Although the last time she’d seen him, her helmsman Demetrios had said the ship was in need of some upkeep if they were to make any voyage north again. As usual he was evasive on the details.

‘It’s not enough though, is it?’ Erlan offered her the cup but she refused it with a flick of her hand. This argument was stale, each time they had it more frustrating than the last. ‘Even if we made it back, what then?’

‘The longer Thrand holds the Twin Kingdoms, the harder it will be to take them from him. He’s destroying Sveäland. The dream—’

‘You don’t know that for certain,’ he said, his voice clipped with impatience. ‘Dream or none.’ He threw the rest of the wine down his throat and sagged back into the pillow. As if even impatience was too heavy a burden for him to bear for long.

‘I feel it. That’s enough for me.’

Thrand was the last surviving son of King Harald Wartooth. Brother to her own dead husband, and the man who had taken from her the throne, her lands… and worse. Thrand hated her people as much as she loved them. She feared to think what he had done to her beloved homeland.

‘You know I want to help you, Lilla. But we’d need an army to stand any chance against Thrand and his hirds. Not a dozen ale-sot river-men and a leaky boat.’ He gave a snort of disgust. ‘By the Hanged! Gerutha’s dead. Einar’s dead. Aska is dead…’ His words trailed away, and for a moment it felt as if the ghosts of their friends – her murdered servant, his fallen comrade, even his wretched dog – filled the silence between them. When he spoke again, it was barely more than a whisper. ‘Maybe it’s time that—’

‘What?’ she snapped. ‘Time that I give it up?’

‘Yes,’ he said, his voice as tender as it was insistent. ‘Make peace that we are here and Thrand is there, and…’

‘And what?’

‘And that Sveäland is lost to you.’

‘How can you say that? We agreed—’

‘I know what we agreed.’ He rubbed at his temples, squeezing his eyelids shut, as if he could crush all the thoughts racing behind them. ‘I wanted to go back… Part of me still does. But… maybe I have to accept there’s nothing left for me in the north either. Those ships were burned a long time ago.’

This was the voice of defeat. It sat ill on the tongue of Erlan Aurvandil, the ‘Shining Wanderer’… Shining no more, she thought, feeling at once sorry and angry at him. Like a sun that has dimmed.

But she understood whence his reluctance came. She knew all of him now. He had held nothing back. In his shoes, would she want to return? Or would she hesitate, too?

She reached out, traced a fingertip down the scar on his cheek. His eyes opened, flicked up to hers. Those dark eyes that still saw right through her. ‘I can’t let it go, Erlan. I can’t dream the same dream every night. This place is a gilded cage. I’ll go mad if I stay here.’

‘Then at least wait,’ he said. ‘It’s too late in the year to leave now anyway. The land would be ice-locked before we reached halfway home. Who knows? By spring the emperor might feel more secure. He may help us like he said.’

‘I saved his daughter. So did you. If Leo doesn’t feel the weight of that debt now, he never will.’

‘I’m telling you, have patience.’

Patience? She snorted. ‘You don’t want me to wait. You want me to give it up.’

‘Well, is that so wrong?’ he exclaimed. ‘By the Hanged, don’t you know how much I love you, Lilla? I don’t want to lose you, not now I have you. I’ve lost everything else… Everything.’ He raked his fingers through his hair. ‘Besides… we’d be walking into a bear trap.’

‘You don’t know what the Weavers of Fate intend.’

‘Nothing good,’ he snarled. ‘They never do. That much I know.’

‘The fates of men are graven on the World Tree,’ she murmured. ‘I must return – even if it means death.’

‘Why must you return…? So you have bad dreams.’ He tapped his own skull. ‘You should try sleeping a night in my head.’ A tear glinted in the corner of his eye like a jewel, then fell in a silver trail down his cheek. He knuckled his brow, squeezing his eyes shut again. ‘These thoughts, so many terrible, mad thoughts. I see fire and blood and rage. Ringing steel… and death.’

‘My love.’ She reached out, put a soothing hand to his face. ‘My love…’

‘I don’t need your sympathy.’ He palmed away the tear. ‘I just need you to give this up.’

‘I can’t. I will not—’

‘I don’t understand.’ Suddenly he sat bolt upright, more alive than she’d seen him in weeks, seizing her hands. ‘Why this urgency? Why this obsession with regaining what he took from you? Tell me! Why? I need to know.’

He squeezed her fingers so tight it hurt. As if physical pain could make her forget the wrong done to her. Could make her forgive.

‘Because,’ she hissed, her voice cold as the northern snows, ‘… he raped me. The boar in my dream is Thrand… He raped me.’

The words hung there between them, vomited up from inside her at last. And into the void left behind them rushed pain and shame and fury. Erlan did not move. She saw his dark eyes flash with incomprehension… and then fill with pity. Which stung her far worse.

‘He raped me.’ She could speak more calmly now. ‘And I mean to make him pay for it. For that, my love, I will not wait.’

CHAPTER TWO

Gravel crunched uncertainly under Erlan’s boot.

His mere presence in the imperial gardens felt like a stain on them as he limped like an intruder past rows of perfectly manicured spice-beds, low hedges with corners cut sharp as blocks of marble, spreading cedar trees, pergolas heaving under their winding vines. It was a place of peace. Of order, of design. And here he was, an alien. An agent of chaos. Of destruction and death.

Was that the inevitable course of a warrior? Each cut of the blade carrying him into a deeper sense of dissonance with the world around him. He had certainly come to feel it in this place.

Even so, he came here often. It was here that he had buried his dog. He had lain Aska’s body in a hole under the shadow of the sea-wall with as much reverence as he would a fallen comrade, marking the spot with a bit of broken stone which any visitor to the garden might have thought fallen from the wall above.

Aska was his secret.

He knelt down in the earth before the stone and closed his eyes, the scent of the nearby laurel bushes filling his nostrils.

Funny, that a dog had come to mean so much to him. That the loss of him was as painful as any Erlan had endured. Sure, Aska had saved his life once and been a faithful companion to his end. But maybe it was more than the dog he’d lost. Maybe something of himself had died with Aska and lay here in the ground. Some part of him that bound him to the north. Here, too, he remembered Kai – his blood-brother whose laugh he could still hear if he closed his eyes. And the scar burned across his heart like a branding-mark when he thought of Inga. Sister. Lover. Mother of his child. All three and yet nothing but bones in the black earth of Vendlagard now. Even his blade, Wrathling, the famed ring-sword of his people – a hero’s sword – which had served his forefathers so well. Served him no less. Lying on the sea-bed now, under the Bosporus’s shifting currents. And there it would lie until the Ragnarok. Perhaps part of him would lie with it until the Final Fires too.

Aye, there were many things to remember.

Each death diminished him, stripping him limb by limb until he no longer knew who he was. Two lives. Two names. Erlan. Hakan. But which was he?

Who was he?

Perhaps neither now. Perhaps there was a third man buried deep inside him, under the caked blood of a hundred deaths, lost in the cacophony of a thousand screams, trying to find his way out.

His eyes closed, his fingers dug into the loamy soil of the seed-bed, and he listened. Listened to the gentle rush of the wind through the crenellations of the sea-wall, to the trilling calls of the turtle-doves which fluttered among the tops of the ornamental trees, to the faint crunch of a gardener’s footsteps elsewhere in the gardens as he toiled to keep all around them beautiful and serene.

Yet, behind it, softer still, he heard the ring of steel, the rending of shields, the dull sound of ripping flesh. It was always there. The skirling winds of Skogul’s storm.

The truth was he was tired. Part of him still longed to return, to see his father again, to feel those strong arms pulling him close, to smell the familiar tang of salt and sweat fused into his woollen tunic. But another part – that unknown part – felt like he had already died.

Had he not earned his rest? What was glory or victory worth if it did not win a man the right to rest? To cease the slaughter. To lie down and breathe. If only for a while. Long enough for that third man to dig his way out.

That was all he wanted.

And yet now Lilla’s burden had become his.

After the first rush of her anger, her tears had come. He had held her, listening to the grim details come pouring from her lips, feeling her rage infecting him like a fever, as if her blood was somehow coursing through his veins, filling his muscles and his limbs, until he had to thrust her away from him and get up and pace the room, so smothering was the violence he felt for Thrand.

It was too much for him to bear – too much for her – this weight of vengeance. A burden so great that it was bound to crush them both. To destroy their love…

Aye, he thought ruefully. If love is what we have. He wasn’t so sure anymore.

Everything in him was a blunt edge. Every feeling, every thought. He was a blade that had seen one too many battles. Nicked and notched and dull. He wondered what it would take to become sharp again. To love with passion. To live with purpose. To stand up, to shout, to run—

Piss on it, he snorted to himself. He never had been much of a runner.

From somewhere behind him came the sound of footsteps on the gravel. Faint at first, but drawing closer, purposeful. A soldier’s gait. He glanced over his shoulder towards the main path and saw two guards dressed in white cloaks with purple trim talking to the gardener. Excubitors – the so-called ‘Sentinels’ who guarded the imperial palace. He watched from the shadow of the wall as the gardener raised a grubby hand and pointed in his direction.

Discovered, then.

He sighed and turned back to Aska’s grave, knowing time was short, staring down at the stone. And behind the tramp of the Sentinels’ sandals, other words came into his mind, soft and unbidden. The words of the Vala, words that had haunted him since the night she spoke them:

You will bear much pain, you Chosen Son – but you will never break. You will fall and rise again.

Some men might take them as a curse. For him, they were a promise. Of life.

…In the end, life.

‘My lord Aurvandil,’ said a voice behind him, gruff and formal.

Erlan turned and acknowledged the two Sentinels with a nod. ‘What is it?’ he said in Greek, a tongue that was second nature to him now.

‘His Holy Majesty, Emperor Leo, third of his name, commands that you attend him.’

‘When?’

‘At once, my lord.’

Erlan grunted. Of course. If an emperor wants to see you, could there be any other answer? ‘Very well, kentarch. Give me a moment.’

The kentarch hesitated, perhaps deliberating for a second. Then he gave a curt nod of acquiescence and the pair withdrew a few paces to the main path. Erlan turned to bid Aska farewell.

‘I will fall… and rise again,’ he murmured to himself, laying his hand gently on the stone. ‘Unlike you, old friend. Rest well.’

Aye. For Lilla’s sake, he must rise again.

One day there might come a time for him to rest. But not today.

Erlan got to his feet, dusted off his knees.

Not yet.

CHAPTER THREE

Far above the eunuch, a panoply of stars glistened out of the black like a scattering of diamonds. Like the diamonds that should have been his. Would have been his, were it not for one man.

Erlan Aurvandil.

Katāros breathed the Northman’s name to the pitiless night like a prayer. As if his hatred could become a physical thing and fly like an arrow-shaft through the heavens, searching the earth till it found its mark. But for him, the City would have fallen. But for him, Katāros’s revenge would have been complete. But for him, glory and riches.

But for him…

The sea was calm now. A calm which, after the violence of the storms, seemed to mock at the eunuch’s fate.

The Caliph’s forces had finally withdrawn a year to the day after they had first laid siege to Byzantium. And Katāros had been forced to leave with them. After all, his betrayal of the emperor and the City was too widely known for him to stay; he had chosen his side, and chosen poorly. By then, the Arabs were a ragged, broken force, slinking away from Byzantium’s unbreached walls like a whipped dog with its tail between its legs. Prince Maslama’s armies had been starved and smashed. The Caliph’s fleet bottled up and ground down to a husk of what it had been – the emperor’s fire-runners had seen to that. Even so, when the Arab fleet quit Byzantium, it numbered nearly a hundred ships, the men aboard fleeing at least to fight another day.

What they hadn’t known was that disaster was to be added to the shame of their defeat. The storm fell on them like the fist of God somewhere in the south Aegean. The fleet was scattered. Many were lost.

But somehow, not Katāros. He had been spared… at least so far.

And yet, he was helpless. Helpless and powerless, a pitiable creature under the great vault of God’s sky, adrift now in the eastern Inner Sea. Its dark waters lapped against the piece of broken decking on which he lay, and had lain for two days. His sole comfort was that he would not have to lay there many days more. For there could be only two outcomes for him, and one of them would not be long in coming. Either thirst would drive him into madness and thence into the arms of death. Or else a passing ship must pluck him from this solitary fate. A fate as stark as it was simple.

No one else on that ship had survived, he was certain of that. The storms had been relentless, ceaseless… unnatural. Or maybe supernatural. For even a man as faithless as Katāros could discern in those whirling gales God’s grim judgement against the heirs of the Prophet. Prince Maslama and his Arab host had boasted of so much, believed so much. They would win the whole world to the Prophet’s cause! And yet what had they accomplished? Nothing, except the utter destruction of the mightiest combined force of land and sea that the world had ever known.

Failure. Total failure… and now Maslama and the rest of those peacocking fools had dragged him down with them. He, who had been the brightest star in the empire, whose beauty knew no rival, even among the finest courtesans of the City. He had made his choice. Thanks to the Northman, it was the wrong one. Providence had been unforgiving of his mistake.

A shiver rippled through Katāros’s salt-raw limbs as he recalled the horrors of the storm. Weak, wounded, hungry men had been cast into the water. Ship had been flung against ship with brutal force, then swallowed up into the maw of the insatiable sea.

How had he survived?

Katāros could no more account for that than any other occurrence in this senseless world. Blessings and curses, favour and infamy – the shadow of these fell over a man like clouds skudding with the wind, whoever he was, whatever he did.

The Lord gives, and the Lord takes away, he thought bitterly. So prated the priests in every basilica of the City. What cringing fool would worship such a fickle god? But whether he longed for death or for life, this capricious Deity – the Great Equivocator in the heavens – gave to him neither.

Night turned to day again.

His throat was swollen, each breath sibilant as a cobra’s hiss. The old wound between his legs, the great absence there, stung like a branding from the saltwater.

Hours passed. His ears rang. His listless body rose and fell with the swell of the sea. The sun coursed by like a great eye of judgement overhead.

And then…

…Something else.

Some other sound now, prodding at his callused senses. Faint as a whisper. Gentle as a promise.

His chest rumbled then with a mirthless laugh, too weak to escape his salt-swelled throat. He heard voices. The clunk of wood. Splashes in the water. And all he could think was: I’m still here, you bastard… still alive.

Though whether he addressed God or the Devil or only himself, he could not have said.

The first two days Katāros could do little but lay out on the fore-deck in the shade of a scrap of old hemp-cloth flapping in the breeze. It made for a contemptible shelter, but still it kept the worst of the sun off him. He lay with his eyes closed, listening to a gruff voice speaking now and then in a dialect he couldn’t understand. Eventually, when he could bear to open his eyes a little he discovered he was aboard a small fishing boat, barely ten strides from bow to stern, hardly four gunwale to gunwale across its belly, and the voice belonged to its captain.

The man was wind-bronzed with a greying beard and a white head-cloth wound round his head against the sun. He was often grunting orders at his two young crewmen. He looked to be Latin by blood, while the boys were darker-skinned and wore only simple tunics that stopped at the knee. It was they who took turns caring for Katāros when all he could do was lie there, helpless as a newborn. One of them was almost tender, resting Katāros’s head in his lap, smoothing down his long hair, even caressing his cheek, as he murmured an old song of the sea and tried to coax stale water down his throat.

On the third morning, after a long and heavy sleep, Katāros was ready to speak.

He sat up, feeling at once a dizzy rush of blood from his head. He clutched his knees to steady himself and waited for his vision to clear.

‘Ho-hoa! Look there, lads, our siren awakes!’ cried the skipper, in a rough dialect of the Greek tongue.

Above Katāros, the wind rapped at the sail. He smelled the reek of unwashed tuna casks. ‘Where… where are you taking me?’ Each word scraped out of his throat.

‘Pete’s bones, don’t worry your head about that! Least for now. Here.’ The fisherman seized a skin and tossed it over, landing it in the eunuch’s lap. ‘Drink!’

Katāros stared stupidly down at the skin, his long black hair hanging like ropes about his face.

‘Well, go on, woman, drink it,’ urged the fisherman. ‘It’ll do you good.’

‘I… I am no woman.’ The pitch of his voice was still high, floating in that nowhere place between the sexes. But by God, his throat was raw, the sea air having scoured the smooth timbre of his voice to a rusty croak.

‘No woman?’ The fisherman frowned, doubtless taking in the fine bone structure of the eunuch’s hairless jaw, his thin, straight nose, the salt-stiff cataracts of dark hair. Hard to disbelieve the evidence of your own eyes, and Katāros recognised in the man’s gaze the barely veiled suspicion which he had seen in so many eyes before. ‘You must forgive me, friend. Only, when the lads cleaned you up—’

‘I am neither man nor woman,’ Katāros cut him off, irked to be explaining himself to some lowly fisherman. ‘I am… what I am.’

The other gave a decisive nod. ‘Well, makes no odds with me, my friend… Still, no offence meant. Anyhow, drink up, drink up. You need to build up your strength.’

‘My thanks to you. To all of you.’ Katāros raised his creaking voice past the old man to the two youths lurking in the stern. Their eyes were riveted on him. ‘I suppose I should be dead.’

‘That you should! But seems the hand of providence scooped you up to some good purpose. God’s will ’n all that.’ The fisherman touched a little amulet hanging around his neck.

God’s will? Katāros took a deep draught on the skin to conceal his scowl. The wine was heavily diluted – a sailor’s drink to quench the thirst, not the rich, dark grape of the emperor’s table he was used to.

‘There’s flatbread, too. And dried hake when you’re ready.’

‘In a while.’ Katāros took another long pull. Mother of God, he could have drunk an ocean. And so he drank and drank, feeling the eyes of all three on him, until his stomach could take no more.

‘Better?’ grinned the old fellow.

‘Some,’ he gasped, licking dry his painfully sun-cracked lips. ‘So then, friend. Where are we headed?’

‘Isle of Malta. And with this wind, we should be in harbour by noon tomorrow.’

‘Malta? Christ’s blood!’ The two boys crossed themselves at his blasphemy. The old man touched his damned amulet again. For once, Katāros might have done the same. Malta was six, maybe seven hundred miles west of where the storms had hit the Arab fleet. The aftermath winds and currents must have carried him past the island of Crete and onward for another five hundred miles or more as he clung like a barnacle to his scrap of decking.

‘Was it far away your vessel foundered?’

Katāros hummed vaguely. ‘Far indeed.’ All three of them were leaned forward over their knees, wanting more. But he had no inclination to tell them more than was necessary. ‘I’m afraid I’m no sailor so I couldn’t tell you exactly. All I know is we were in the southern Aegean… Is Malta your final destination?’ he said, deflecting from the subject.

‘Aye, for now. Home harbour is Massala in the southeast. We’ll be there ten days or so to refit, then we sail back east.’

‘You wouldn’t believe the mass of tunny-fish to be had west of Kithira late summer,’ volunteered the older youth from his seat by the tiller.

‘I’ve no doubt,’ returned Katāros with a flicker of a smile and a flash of his dark brown eyes. Although he had no interest in the comings and goings of a few wretched fish. He was thinking of Malta. That was still imperial territory. And although the chance that word of his treachery to the emperor had reached there was vanishingly small, he wanted to be certain of his anonymity. Recognition would be disastrous. The very idea evoked precise mental images for him – of sharp blades and severed noses; fingers or ears, or God knows which body parts falling to the floor. He of all people knew how the Byzantines were fond of such measures of correction.

Meanwhile, the fisherman’s weather-lined eyes had narrowed at him. ‘Where you from, friend? You don’t look Greek. And you’re surely no Arab.’

‘Varna,’ Katāros lied. It was a port on the western shore of the Euxine Sea. A place suitably far removed from the truth. ‘You know it?’

‘Heard of it.’ The fisherman gave a low whistle. ‘Pete’s bones, you’re a long way from there.’

With one lie told, others came more easily. ‘I was agent to a Bulgar merchant who had trade in Crete. The storm caught us on the last leg into Heraklion. That was four days ago, I think… maybe longer.’

‘Not without fresh water, wouldn’t be. Or we’d have been pulling your corpse out the drink. You the only survivor?’

‘I don’t know.’

The fisherman grunted, scratching thoughtfully at the thick curls of his beard. At length, he seemed to make up his mind and thrust out a hand. ‘The name’s Elias. These here are my boys, Tomas and Andreas.’ The boys nodded, the younger venturing a shy smile. ‘And you are damned lucky – whoever you are, wherever you’re from.’

So now he had their names. In return, no doubt they expected his. Katāros searched for something generic. Something forgettable. ‘They call me Markos.’

‘Well then, Markos. Can’t promise you much when we make land. A change of clothes, maybe. Enough coin for a night or two at an inn. After that, your best bet is to find your way to Melita.’

‘Melita?’

‘The main town on the island.’

‘Forget Melita,’ piped up Tomas, the older son. ‘With a ring like that one, you could buy passage at least as far as Byzantium. My guess is it’d see you all the way home to Varna.’ The boy was staring greedily at Katāros’s hand, where, on his middle finger, he still wore a thick gold ring. It was the official seal of the parakoimo-menos – the High Chamberlain of the Imperial Bedchamber, and one of the most powerful offices in the empire. An office, it need hardly be said, he held no longer.

Instinctively, he turned the seal inside his knuckle.

Seeing this, Elias snapped at his son, ‘No one asked for your opinion, boy.’

‘The lad means no harm.’ Katāros smiled at the prying little weasel. ‘Anyway, he’s right. I must use what little I have to return home.’

Home…

There was another lie. The word had no meaning for him. Not now. Not ever.

‘Let’s see how things fall when we reach harbour,’ said Elias. ‘I’ll ask around. Massala is only a small place but there may be more imperial ships stopping in the bay now the siege of the Great City has lifted… O’ course, you must know all about that.’

Katāros’s eyes shifted between the father and his boys, a sudden instinct for survival pricking him to tread warily. ‘Of course. We wouldn’t have had clear passage through the straits if it had not.’

Elias grinned encouragingly. ‘Go on! What more can you tell?’

‘Oh, little enough. We stopped only briefly in Chalcedon to take on water and provisions. One of the port officials told me the Arab fleet had withdrawn not a week before. They took what was left of their army with them.’

‘We heard it was the Bulgars that really did for ’em,’ said Elias, mopping the sweat from his neck with a filthy rag. ‘That true?’

‘Did for them?’ exclaimed Tomas excitedly. ‘They butchered them to a man, is what we heard!’ He was grinning from ear to ear, the blood-thirsty brat.

‘Not quite to a man, as I understand it,’ corrected Katāros. ‘But I heard their mounted warriors were effective.’ Indeed, he thought bitterly to himself, the Bulgar horde had proved quite the ally to Emperor Leo in the end, although Katāros was loath to admit it. Remembering that it was Erlan Aurvandil who had secured their alliance nettled him worst of all.

Perhaps it was his body’s way of shutting out the unwelcome memory of it all, but he felt a wave of exhaustion wash over him, the wine suddenly filling his head. ‘Listen, friends, I would be happy to share what else I know. But my head is throbbing, you see, and—’

‘Say no more,’ cut in Elias. ‘And God forgive our damn fool questions! Only news is harder to come by than a shoal of swordfish in this line of work, see?’

‘Nothing to forgive,’ murmured Katāros. He lay back on the matting that served as his bed and stretched himself out under the little patch of shade.

Elias reached out and patted his knee. ‘Rest good, my friend. Then eat your fill… you’re safe now.’

Katāros closed his eyes.

Safe?

Alive, yes. But he would never be truly safe until he was well beyond the reach of the long arm of the emperor’s justice. Drowning would be a mercy compared to what that Isaurian brute would mete out on him, should he ever fall into his hands.

And yet, even if he got clear, what dangers might await him beyond the empire’s dominion – a penniless eunuch, weak in body, without a friend in the world, and only his wits to protect him?

Safe? No, indeed. He doubted that.

CHAPTER FOUR

Erlan found the emperor in his private quarters high up in the Daphne wing of the Great Palace, where the mid-morning sun was streaming into the chamber in golden cataracts of light. Leo the Isaurian, third of his name, was bent over his blue-grey desk of Tuscan marble like any imperial accountant, knuckles pressed white on its surface. Strewn before him was a mess of scrolls and parchments.

As he entered, Erlan couldn’t help but mark how ordinary the man looked without his imperial raiment of purple robes and golden diadems. From where he stood, he could see the bald patch spreading from the crown of the Great Lion’s head of dark curls. And when he looked up, how the grey around his temples had bloomed this last year. Like lichen on damp walls.

His eyes were still young, though. Young and thorough and commanding.

‘Aurvandil. Come in.’ The emperor indicated the silver pitcher and a couple of blue glass chalices rimmed with gold on a side-table against the far wall. ‘Help yourself. And one for me. I’ve a thirst like a camel trader on me.’

Erlan obliged. ‘Majesty.’

Leo looked up from his desk and took the chalice Erlan had proffered him. He took a sip. ‘Mother of God, Northman! You’re supposed to cut the stuff with water or I’ll be drunk as a monk before noon.’ He pointed at a little earthenware jug, also on the tray. ‘There… Ah, no matter, no matter now! Here, sit.’ He indicated a stone chair with no back placed before his desk.

Erlan took his seat, unable to prevent himself stealing a glance at the pillar to his right. That was where he had cradled this man’s bleeding head in his lap, wondering whether he would live or die.

That was where I drank his blood, he remembered.

Strange where the Norns’ weaving led a man.

Leo took another gulp of wine and settled back into his chair. ‘How’s the hip?’

‘Better.’

‘The most curious thing, how the smallest wounds can prove the most deadly.’

‘Almost deadly,’ Erlan corrected him.

‘Indeed! Heaven be praised.’ Leo shot a glance skyward.

The wound had only been the rake of an arrow-tip across his hip. Little more than a scratch. Yet the infection had swelled into a hideous bulging purple and black abscess, for weeks suppurating an oily yellow pus. He had been delirious for much of it, a fever from which, were it not for the skills of Leo’s personal physician, and Lilla’s constant vigilance, he might never have woken.

Leo nodded. ‘You have suffered much for my cause. I’ll not forget it. Nor have I forgotten the terms of your service.’

‘The siege is long over. My vow to you fulfilled.’

‘And now you serve your queen.’ Leo sucked his teeth and stood, moving to the doorway that gave out over the Hippodrome and its myriad arches. The tallest of the obelisks that formed the spine of the great amphitheatre was just visible over its walls, the inlaid gold in the stone flashing in the sunlight. ‘How is she, by the way?’

‘She’ll overcome her disappointment, if that’s what you mean… With time.’

The emperor had grace enough to give an equivocal grunt. ‘An unfortunate business – her being caught up in the eunuch’s deception.’ He took another swig on his wine. ‘Pity he escaped.’ He turned and looked Erlan in the eye. ‘And a shame I can’t help her… Of course, I would like to. But expedience binds my hand, you see.’

‘A man in your position has to be practical.’

‘Exactly! That’s exactly it.’

‘Queen Lilla understands your position.’

‘Good, very good. I’m glad… Christ’s blood! Is it such torment to remain here?’ He threw out his hand at the honeycomb facade of the Hippodrome, looming over the palace with monstrous grandeur. ‘Look out there. This is the centre of the world! The jewel in the empire’s crown! Here, she has everything she could ever need. Let her stay, for the love of Christ, let her stay… we will treat her with every honour.’

Erlan knew well what honour Leo had in mind. Lilla had told him that Leo had as good as proposed marriage to her when he feared his own wife was dying. But the Empress Maria had lived, and, more than that, had now borne a male heir for Leo. A cub for the Great Lion. That was a feat beyond Lilla.

‘This city is a wonder,’ Erlan admitted. ‘But it’s not her home.’

‘Did she not come here to make an alliance?’

‘In that, she accepts her failure.’

Leo looked at Erlan, his tongue running over his lips. ‘As I said, I wish I could help her.’ He lifted his chalice and jabbed it accusingly at Erlan. ‘The irony is that you are the reason I cannot.’

‘Me?’

‘You’ve damn near beggared the empire with your wild promises to that Bulgar rogue.’ Leo picked up a piece of vellum unfurled on his desk and flapped it at Erlan. ‘Khan Tervel writes to remind me of what I owe him.’ He shook his head. ‘Three times the annual tribute for this year alone! Oh, and the small matter of the two additional years we failed to pay before I took up the purple. By the blood of all the martyrs, he means to have near a million solidi off us!’ he cried. ‘Did you have any idea what you were committing us to?’

The truth was Erlan would have promised the fat Khan – whose avarice was only matched by his gluttony – double if it meant the Bulgars would honour the treaty. ‘The Bulgar horde came. The city stands. The Arabs are gone. That was surely worth any price.’

‘Easily said, Aurvandil, easily said. But now we have to pay the singer for his song.’

‘Can’t you delay payment?’

‘And risk turning an ally into an enemy?’ Leo scratched irritably at the thinning patch of hair on his crown. ‘No. The siege may be over, but I can’t afford a war on two fronts. The Caliph’s remaining armies are still harrying our cities in the east.’ He pulled out another scroll from the pile, this one a map. The ring of the imperial seal tapped on different places. ‘Cappadocia, Cilicia, Phrygia. All these are still to be cleared. An aggrieved Bulgar is a vengeful one. As like to stick a knife in your back as smile at you. No. Better to pay them now, even if it means a lean couple of years for all of us.’

Erlan glanced around the room. At the tapestries gleaming with golden thread, the silver candlesticks, the silk cushions. He doubted it would be the emperor suffering privation for want of a little gold.

Leo gave a last decisive rap of his ring upon the marble. ‘Which brings me to the reason I summoned you here.’

‘Majesty?’

‘The tribute mission leaves in seven days under General Arbasdos’s command. I would like you to go with them.’

‘Me?’

‘Oh, I know you do not owe me this. But I ask you, as a friend. The Khan knows you.’ He gave an exasperated chuckle. ‘Mother of God, you’re the only one of my courtiers whom the Khan has ever met – and lived!’

Erlan remembered the last time he had visited Khan Tervel in his capital. Pliska was little more than a glorified horse pasture, strewn with animal shit, hole-houses and dangerously capricious savages. They had thrown him in a pit of wolves and the fat Khan had laughed heartily at the fun of it. It was no thanks to him that Erlan had come out of that alive. ‘He knows me, certainly, but—’

‘And he trusts you. If he didn’t, he wouldn’t have let his son ride to our aid with his entire strength.’ Leo leaned forward, knuckles on his desk, the military accountant. ‘You must see how valuable you are personally to preserving this alliance?’

Though he was loath to admit it, Erlan could see reason in the emperor’s request. But he felt like a boar being driven into a pit and didn’t like it. Besides which, the prospect of spending even an hour in the company of General Arbasdos was hardly something he relished. ‘Do you want an answer now, Majesty?’

The emperor eased himself further back into his chair and threaded his fingers on his chest. ‘Many would consider the wish of an emperor tantamount to a binding command, Aurvandil.’ He regarded Erlan with that unflinching eye. ‘But if you need time… I’ll have your answer tomorrow morning.’ With an abrupt snap of his wrist, he snatched up another parchment from the top of the pile and threw it down before him. ‘That is all.’

Erlan set down his cup. ‘Majesty.’ He gave a curt bow and went to the door. Was almost through it when the emperor called after him, ‘Oh, when you do think on it, Aurvandil… Consider the goodwill you have won among us.’ He peered up at Erlan. ‘It would be a shame to jeopardise that, would it not?’

‘I will think on it with care, Majesty,’ Erlan assured him, and closed the door behind him.

But he already knew his answer. Goodwill or none, the fate of Byzantium was no longer his concern.

CHAPTER FIVE

Lilla’s hand went to the cross nestled in the crucible of her neck as she swept along the corridor, feeling grateful for the cool air of the palace interior after the blistering heat of the day.

The pendant was solid gold, dull with the patina of age, and marked with symbols in the Greek tongue. Lilla knew not what they signified exactly. Something about Christ the Saviour, as the citizens of Byzantium called him. Or simply the Lord Jesus, as Gerutha had known him. Sweet Grusha… They had found the ornament clutched in her lifeless hand, covered with her own blood.

That terrible night of fire…

Grusha had found comfort in this foreign deity, so different from the gods of the north. Her body was ashes now. Part of Lilla felt the pendant should have burned with Gerutha on her funeral pyre since it had meant so much to her. But in spite of that, she had kept the cross for herself. A memory of her friend, a whisper of her spirit, that would always be close.

Lilla felt a sudden pang of anger. Grusha had deserved a better end than the cheap betrayal which the servant-girl Yana and the eunuch Katāros had wrought between them. But the threads of fate had bound her, as they bound every soul. And so it was…

Lilla came to the large studded door to her chambers. Lifting the latch, she wondered what Grusha would counsel her now. Her trip to Chalcedon had wasted an entire day. Demetrios had nothing remotely useful to tell her. Indeed, it was worse than that. There now seemed to be some mischief brewing amongst the crew. Nothing he couldn’t handle, Demetrios assured her. ‘They’re just bored,’ he said. ‘They feel stuck here and some of them feel cheated.’

Aye, she thought. Them and her both.

Inside the chamber, it was already dark. An oil lamp was burning in the corner, its orange flame affording the room no more than a sepulchral glow.

Her feet were sore. She slipped off her shoes and stood for a moment savouring the kiss of cool marble on her weary soles. But it was no balm to the irritation in her heart.

According to Demetrios, it was she whom the crew held responsible for their predicament. She had lost half their number. She had got them stranded on the far side of the world. As if she held sway over the tide of war that had engulfed them all in its flood.

She sighed, trying and failing not to count up the improbabilities weighed against her. A half-mutinous crew, a ship in need of repair. Even Erlan, her closest ally, seemed hardly the man he had once been.

In spite of the day’s frustrations, she didn’t want to go to bed at once. Instead she was drawn towards the beams of moonlight lancing in through the quavering drapes. She scooped up a cup of wine left out by her servant and went onto the balcony to gaze out over the shimmering waters of the Straits.

The moon was still rising, bathing everything in its wan light – the roofs of the city, the sea-walls, even the distant hills of Asia strangely illumined as if gilt with silver. The air still smelled of the dust and heat of the day, the scents of the spice district drifting over the city.

Patience. Is that the lesson Gerutha would want to teach her?

To wait, to bide her time, to be content in this gilded cage – just as Erlan had counselled her. By all the gods, how she wished she could be content. For the old Lilla, the young woman she used to be, that might have been enough. But now… now she was hard inside, like a blade tempered in fire, and something deeper and altogether darker hid within her heart that would not let her rest.

A noise sounded faintly from within the chamber. When silence followed, she thought it must have been a trick of her mind, or perhaps Erlan stirring in his sleep. Instead, she took a long draw on her spiced wine, relishing the mellow mix of Cretan grape and spikenard.

The first she knew of him was a hand coiling round her waist, then the warmth of his hard body as he drew her back against him.

‘You’re late.’ Erlan’s lips brushed over the crook of her neck, light as silk. ‘I thought you must have drowned.’

‘I might as well have for all the good the trip did us. There’s trouble with the crew.’

‘What…kind…of…trouble?’ Between each word, he shed a kiss on her nape, sending rivers of pleasure down her spine.

‘The crew despise me. So Demetrios says.’

‘Honey-coating it, is he?’

‘I don’t blame them. They’ve been too long in this place. Like us…’ She pulled the pin from her carefully constructed coiffure and shook out her mane of blonde hair. ‘Dear gods, what I would not give to leave this city?’

Erlan blew out a long sigh. The kind before a man makes a confession. ‘Well… seems the emperor has given me a chance to do just that.’

‘What?’ She spun around. ‘How?’

‘He’s sending a tribute mission to the Bulgars. He wants me to accompany them as envoy. Says because I’ve met the Khan before, I’m key to its success. I have my doubts. He’s given me till tomorrow to accept.’

‘And will you?’

He smiled and squeezed her arms. ‘Lilla… I’m not leaving you again.’ He pulled her close to him.

She lay her head against his chest, listening to the beat of his heart, thoughts stirring in her head. ‘A tribute mission?’ she said at length. ‘What kind of tribute?’

‘Gold – what else? Near a million solidi, Leo told me.’

‘A million?’ Lilla gaped in astonishment. And all at once she felt a crack in the crushing walls of her frustration.

‘Although what in the Nine Worlds a puffed-up horse-herder like Tervel will do with a million solidi—’

‘Erlan, don’t you see! This is our way out.’

‘What is?’

She laughed suddenly. ‘By the stars, elskling, your eyes are far too honest! Can’t you see what’s under your nose?’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘How many spears would that much gold buy in Sveäland? How many sell-swords? How many lords and their hirds come to that?’

‘A fair number, true, but—’

‘Five thousand… no, ten thousand!’

‘Perhaps more, but… wait, you’re not suggesting—’

‘We steal it!’

‘Steal it? You’ve lost your wits.’

‘I don’t know,’ she laughed. ‘Maybe I have.’ Yet for the first time in an age, she felt a tiny ember of joy glow in her heart. ‘When does the mission leave?’

‘Seven days, he said.’

‘Only seven? By land or sea?’

‘That much gold, by sea, I suppose. But—’

‘So much the better.’ She clapped her hands in delight. ‘We intercept them. Steal the gold. And be on our way. They’ll never catch us. Not once Fasolt finds her wings.’ She felt giddy with excitement.

‘Wait, slow down, woman. Quite apart from the question of how we’re supposed to separate forty thousand-odd marks of gold from its escort… think what would happen if we succeeded.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You realise the position it would leave the emperor in?’

‘Hel take Leo! And Hel take his empire!’ she snarled, her anger flaring even quicker than her mirth. ‘I owe them nothing. Not after what they did to me.’