0,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

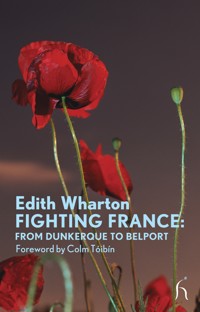

In "A Son at the Front," Edith Wharton delves into the emotional and societal upheavals wrought by World War I, exploring the profound toll of the conflict on personal lives and relationships. Written in her distinctive prose, characterized by a keen psychological insight and nuanced character development, the narrative centers on George, a father grappling with the loss of his son to the war. Wharton's literary style combines realism with a subtle critique of American society'Äôs response to the war, contrasting patriotic fervor with personal grief, and thereby exposing the fragility of human connections amidst global chaos. Edith Wharton, an eminent American novelist and a keen observer of her society, was profoundly affected by the events of World War I. Having witnessed the shifting values and cultural disillusionment around her, she was moved to pen this poignant tale that reflects both her literary prowess and her empathy for those caught in the crossfire of war. Her own experiences of living in Europe during the war enriched her understanding of the nuanced emotional landscapes traversed by her characters. This novel is a compelling meditation on love, loss, and the often harsh realities of warfare, making it essential reading for those interested in the human condition during times of crisis. Wharton's deft exploration of the intersection of personal and political will resonate with readers, urging them to reflect on the enduring impact of war on society and the individual.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

A Son at the Front

Table of Contents

BOOK I

I

John Campton, the American portrait-painter, stood in his bare studio in Montmartre at the end of a summer afternoon contemplating a battered calendar that hung against the wall.

The calendar marked July 30, 1914.

Campton looked at this date with a gaze of unmixed satisfaction. His son, his only boy, who was coming from America, must have landed in England that morning, and after a brief halt in London would join him the next evening in Paris. To bring the moment nearer, Campton, smiling at his weakness, tore off the leaf and uncovered the 31. Then, leaning in the window, he looked out over his untidy scrap of garden at the silver-grey sea of Paris spreading mistily below him.

A number of visitors had passed through the studio that day. After years of obscurity Campton had been projected into the light—or perhaps only into the limelight—by his portrait of his son George, exhibited three years earlier at the spring show of the French Society of Painters and Sculptors. The picture seemed to its author to be exactly in the line of the unnoticed things he had been showing before, though perhaps nearer to what he was always trying for, because of the exceptional interest of his subject. But to the public he had appeared to take a new turn; or perhaps some critic had suddenly found the right phrase for him; or, that season, people wanted a new painter to talk about. Didn’t he know by heart all the Paris reasons for success or failure?

The early years of his career had given him ample opportunity to learn them. Like other young students of his generation, he had come to Paris with an exaggerated reverence for the few conspicuous figures who made the old Salons of the ’eighties like bad plays written around a few stars. If he could get near enough to Beausite, the ruling light of the galaxy, he thought he might do things not unworthy of that great master; but Beausite, who had ceased to receive pupils, saw no reason for making an exception in favour of an obscure youth without a backing. He was not kind; and on the only occasion when a painting of Campton’s came under his eye he let fall an epigram which went the round of Paris, but shocked its victim by its revelation of the great man’s ineptitude.

Campton, if he could have gone on admiring Beausite’s work, would have forgotten his unkindness and even his critical incapacity; but as the young painter’s personal convictions developed he discovered that his idol had none, and that the dazzling maëstria still enveloping his work was only the light from a dead star.

All these things were now nearly thirty years old. Beausite had vanished from the heavens, and the youth he had sneered at throned there in his stead. Most of the people who besieged Campton’s studio were the lineal descendants of those who had echoed Beausite’s sneer. They belonged to the types that Campton least cared to paint; but they were usually those who paid the highest prices, and he had lately had new and imperious reasons for wanting to earn all the money he could. So for two years he had let it be as difficult and expensive as possible to be “done by Campton”; and this oppressive July day had been crowded with the visits of suppliants of a sort unused to waiting on anybody’s pleasure, people who had postponed St. Moritz and Deauville, Aix and Royat, because it was known that one had to accept the master’s conditions or apply elsewhere.

The job bored him more than ever; the more of their fatuous faces he recorded the more he hated the task; but for the last two or three days the monotony of his toil had been relieved by a new element of interest. This was produced by what he called the “war-funk,” and consisted in the effect on his sitters and their friends of the suggestion that something new, incomprehensible and uncomfortable might be about to threaten the ordered course of their pleasures.

Campton himself did not “believe in the war” (as the current phrase went); therefore he was able to note with perfect composure its agitating effect upon his sitters. On the whole the women behaved best: the idiotic Mme. de Dolmetsch had actually grown beautiful through fear for her lover, who turned out (in spite of a name as exotic as hers) to be a French subject of military age. The men had made a less creditable showing—especially the big banker and promoter, Jorgenstein, whose round red face had withered like a pricked balloon, and young Prince Demetrios Palamèdes, just married to the fabulously rich daughter of an Argentine wheat-grower, and so secure as to his bride’s fortune that he could curse impartially all the disturbers of his summer plans. Even the great tuberculosis specialist, Fortin-Lescluze, whom Campton was painting in return for the physician’s devoted care of George the previous year, had lost something of his professional composure, and no longer gave out the sense of tranquillizing strength which had been such a help in the boy’s fight for health. Fortin-Lescluze, always in contact with the rulers of the earth, must surely have some hint of their councils. Whatever it was, he revealed nothing, but continued to talk frivolously and infatuatedly about a new Javanese dancer whom he wanted Campton to paint; but his large beaked face with its triumphant moustache had grown pinched and grey, and he had forgotten to renew the dye on the moustache.

Campton’s one really imperturbable visitor was little Charlie Alicante, the Spanish secretary of Embassy at Berlin, who had dropped in on his way to St. Moritz, bringing the newest news from the Wilhelmstrasse news that was all suavity and reassurance, with a touch of playful reproach for the irritability of French feeling, and a reminder of Imperial longanimity in regard to the foolish misunderstandings of Agadir and Saverne.

Now all the visitors had gone, and Campton, leaning in the window, looked out over Paris and mused on his summer plans. He meant to plunge straight down to Southern Italy and Sicily, perhaps even push over to North Africa. That at least was what he hoped for: no sun was too hot for him and no landscape too arid. But it all depended on George; for George was going with him, and if George preferred Spain they would postpone the desert.

It was almost impossible to Campton to picture what it would be like to have the boy with him. For so long he had seen his son only in snatches, hurriedly, incompletely, uncomprehendingly: it was only in the last three years that their intimacy had had a chance to develop. And they had never travelled together, except for hasty dashes, two or three times, to seashore or mountains; had never gone off on a long solitary journey such as this. Campton, tired, disenchanted, and nearing sixty, found himself looking forward to the adventure with an eagerness as great as the different sort of ardour with which, in his youth, he had imagined flights of another kind with the woman who was to fulfill every dream.

“Well—I suppose that’s the stuff pictures are made of,” he thought, smiling at his inextinguishable belief in the completeness of his next experience. Life had perpetually knocked him down just as he had his hand on her gifts; nothing had ever succeeded with him but his work. But he was as sure as ever that peace of mind and contentment of heart were waiting for him round the next corner; and this time, it was clear, they were to come to him through his wonderful son.

The doorbell rang, and he listened for the maidservant’s step. There was another impatient jingle, and he remembered that his faithful Mariette had left for Lille, where she was to spend her vacation with her family. Campton, reaching for his stick, shuffled across the studio with his lame awkward stride.

At the door stood his old friend Paul Dastrey, one of the few men with whom he had been unbrokenly intimate since the first days of his disturbed and incoherent Parisian life. Dastrey came in without speaking: his small dry face, seamed with premature wrinkles of irony and sensitiveness, looked unusually grave. The wrinkles seemed suddenly to have become those of an old man; and how grey Dastrey had turned! He walked a little stiffly, with a jauntiness obviously intended to conceal a growing tendency to rheumatism.

In the middle of the floor he paused and tapped a varnished boot-tip with his stick.

“Let’s see what you’ve done to Daisy Dolmetsch.”

“Oh, it’s been done for me—you’ll see!” Campton laughed. He was enjoying the sight of Dastrey and thinking that this visit was providentially timed to give him a chance of expatiating on his coming journey. In his rare moments of expansiveness he felt the need of some substitute for the background of domestic sympathy which, as a rule, would have simply bored or exasperated him; and at such times he could always talk to Dastrey.

The little man screwed up his eyes and continued to tap his varnished toes.

“But she’s magnificent. She’s seen the Medusa!”

Campton laughed again. “Just so. For days and days I’d been trying to do something with her; and suddenly the war-funk did it for me.”

“The war-funk?”

“Who’d have thought it? She’s frightened to death about Ladislas Isador—who is French, it turns out, and mobilisable. The poor soul thinks there’s going to be war!”

“Well, there is,” said Dastrey.

The two men looked at each other: Campton amused, incredulous, a shade impatient at the perpetual recurrence of the same theme, and aware of presenting a smile of irritating unresponsiveness to his friend’s solemn gaze.

“Oh, come—you too? Why, the Duke of Alicante has just left here, fresh from Berlin. You ought to hear him laugh at us....”

“How about Berlin’s laughing at him?” Dastrey sank into a wicker armchair, drew out a cigarette and forgot to light it. Campton returned to the window.

“There can’t be war: I’m going to Sicily and Africa with George the day after to-morrow,” he broke out.

“Ah, George——. To be sure....”

There was a silence; Dastrey had not even smiled. He turned the unlit cigarette in his dry fingers.

“Too young for ’seventy—and too old for this! Some men are born under a curse,” he burst out.

“What on earth are you talking about?” Campton exclaimed, forcing his gaiety a little.

Dastrey stared at him with furious eyes. “But I shall get something, somewhere ... they can’t stop a man’s enlisting ... I had an old uncle who did it in ’seventy ... he was older than I am now.”

Campton looked at him compassionately. Poor little circumscribed Paul Dastrey, whose utmost adventure had been an occasional article in an art review, an occasional six weeks in the near East! It was pitiful to see him breathing fire and fury on an enemy one knew to be engaged, at that very moment, in meeting England and France more than half-way in the effort to smooth over diplomatic difficulties. But Campton could make allowances for the nerves of the tragic generation brought up in the shadow of Sedan.

“Look here,” he said, “I’ll tell you what. Come along with George and me—as far as Palermo, anyhow. You’re a little stiff again in that left knee, and we can bake our lamenesses together in the good Sicilian oven.”

Dastrey had found a match and lighted his cigarette.

“My poor Campton—there’ll be war in three days.”

Campton’s incredulity was shot through with the deadly chill of conviction. There it was—there would be war! It was too like his cursed luck not to be true.... He smiled inwardly, perceiving that he was viewing the question exactly as the despicable Jorgenstein and the fatuous Prince Demetrios had viewed it: as an unwarrantable interference with his private plans. Yes—but his case was different.... Here was the son he had never seen enough of, never till lately seen at all as most fathers see their sons; and the boy was to be packed off to New York that winter, to go into a bank; and for the Lord knew how many months this was to be their last chance, as it was almost their first, of being together quietly, confidentially, uninterruptedly. These other men were whining at the interruption of their vile pleasures or their viler money-making; he, poor devil, was trembling for the chance to lay the foundation of a complete and lasting friendship with his only son, at the moment when such understandings do most to shape a youth’s future.... “And with what I’ve had to fight against!” he groaned, seeing victory in sight, and sickening at the idea that it might be snatched from him.

Then another thought came, and he felt the blood leaving his ruddy face and, as it seemed, receding from every vein of his heavy awkward body. He sat down opposite Dastrey, and the two looked at each other.

“There won’t be war. But if there were—why shouldn’t George and I go to Sicily? You don’t see us sitting here making lint, do you?”

Dastrey smiled. “Lint is unhygienic; you won’t have to do that. And I see no reason why you shouldn’t go to Sicily—or to China.” He paused. “But how about George—I thought he and you were both born in France?”

Campton reached for a cigarette. “We were, worse luck. He’s subject to your preposterous military regulations. But it doesn’t make any difference, as it happens. He’s sure to be discharged after that touch of tuberculosis he had last year, when he had to be rushed up to the Engadine.”

“Ah, I see. Then, as you say.... Still, of course he wouldn’t be allowed to leave the country.”

A constrained silence fell between the two. Campton became aware that, for the first time since they had known each other, their points of view were the width of the poles apart. It was hopeless to try to bridge such a distance.

“Of course, you know,” he said, trying for his easiest voice, “I still consider this discussion purely academic.... But if it turns out that I’m wrong I shall do all I can—all I can, do you hear?—to get George discharged.... You’d better know that....”

Dastrey, rising, held out his hand with his faithful smile. “My dear old Campton, I perfectly understand a foreigner’s taking that view....” He walked toward the door and they parted without more words.

When he had gone Campton began to recover his reassurance. Who was Dastrey, poor chap, to behave as if he were in the councils of the powers? It was perfect nonsense to pretend that a diplomatist straight from Berlin didn’t know more about what was happening there than the newsmongers of the Boulevards. One didn’t have to be an Ambassador to see which way the wind was blowing; and men like Alicante, belonging to a country uninvolved in the affair, were the only people capable of a cool judgment at moments of international tension.

Campton took the portrait of Mme. de Dolmetsch and leaned it against the other canvases along the wall. Then he started clumsily to put the room to rights—without Mariette he was so helpless—and finally, abandoning the attempt, said to himself: “I’ll come and wind things up to-morrow.”

He was moving that day from the studio to the Hotel de Crillon, where George was to join him the next evening. It would be jolly to be with the boy from the moment he arrived; and, even if Mariette’s departure had not paralyzed his primitive housekeeping, he could not have made room for his son at the studio. So, reluctantly, for he loathed luxury and conformity, but joyously, because he was to be with George, Campton threw some shabby clothes into a shapeless portmanteau, and prepared to despatch the concierge for a taxicab.

He was hobbling down the stairs when the old woman met him with a telegram. He tore it open and saw that it was dated Deauville, and was not, as he had feared, from his son.

“Very anxious. Must see you to-morrow. Please come to Avenue Marigny at five without fail. Julia Brant.”

“Oh, damn,” Campton growled, crumpling up the message.

The concierge was looking at him with searching eyes.

“Is it war, sir?” she asked, pointing to the bit of blue paper. He supposed she was thinking of her grandsons.

“No—no—nonsense! War?” He smiled into her shrewd old face, every wrinkle of which seemed full of a deep human experience.

“War? Can you imagine anything more absurd? Can you, now? What should you say if they told you war was going to be declared, Mme. Lebel?”

She gave him back his look with profound earnestness; then she spoke in a voice of sudden resolution. “Why, I should say we don’t want it, sir—I’d have four in it if it came—but that this sort of thing has got to stop.”

Campton shrugged. “Oh, well—it’s not going to come, so don’t worry. And call me a taxi, will you? No, no, I’ll carry the bags down myself.”

II

“But even if they do mobilise: mobilisation is not war—is it?” Mrs. Anderson Brant repeated across the teacups.

Campton dragged himself up from the deep armchair he had inadvertently chosen. To escape from his hostess’s troubled eyes he limped across to the window and stood gazing out at the thick turf and brilliant flower-borders of the garden which was so unlike his own. After a moment he turned and glanced about him, catching the reflection of his heavy figure in a mirror dividing two garlanded panels. He had not entered Mrs. Brant’s drawing-room for nearly ten years; not since the period of the interminable discussions about the choice of a school for George; and in spite of the far graver preoccupations that now weighed on him, and of the huge menace with which the whole world was echoing, he paused for an instant to consider the contrast between his clumsy person and that expensive and irreproachable room.

“You’ve taken away Beausite’s portrait of you,” he said abruptly, looking up at the chimney-panel, which was filled with the blue and umber bloom of a Fragonard landscape.

A full-length of Mrs. Anderson Brant by Beausite had been one of Mr. Brant’s wedding-presents to his bride; a Beausite portrait, at that time, was as much a part of such marriages as pearls and sables.

“Yes. Anderson thought ... the dress had grown so dreadfully old-fashioned,” she explained indifferently; and went on again: “You think it’s not war: don’t you?”

What was the use of telling her what he thought? For years and years he had not done that—about anything. But suddenly, now, a stringent necessity had drawn them together, confronting them like any two plain people caught in a common danger—like husband and wife, for example!

“It is war, this time, I believe,” he said.

She set down her cup with a hand that had begun to tremble.

“I disagree with you entirely,” she retorted, her voice shrill with anxiety. “I was frightfully upset when I sent you that telegram yesterday; but I’ve been lunching to-day with the old Duc de Montlhéry—you know he fought in ’seventy—and with Lévi-Michel of the ‘Jour,’ who had just seen some of the government people; and they both explained to me quite clearly——”

“That you’d made a mistake in coming up from Deauville?”

To save himself Campton could not restrain the sneer; on the rare occasions when a crisis in their lives flung them on each other’s mercy, the first sensation he was always conscious of was the degree to which she bored him. He remembered the day, years ago, long before their divorce, when it had first come home to him that she was always going to bore him. But he was ashamed to think of that now, and went on more patiently: “You see, the situation is rather different from anything we’ve known before; and, after all, in 1870 all the wise people thought till the last minute that there would be no war.”

Her delicate face seemed to shrink and wither with apprehension.

“Then—what about George?” she asked, the paint coming out about her haggard eyes.

Campton paused a moment. “You may suppose I’ve thought of that.”

“Oh, of course....” He saw she was honestly trying to be what a mother should be in talking of her only child to that child’s father. But the long habit of superficiality made her stammering and inarticulate when her one deep feeling tried to rise to the surface.

Campton seated himself again, taking care to choose a straight-backed chair. “I see nothing to worry about with regard to George,” he said.

“You mean——?”

“Why, they won’t take him—they won’t want him ... with his medical record.”

“Are you sure? He’s so much stronger.... He’s gained twenty pounds....” It was terrible, really, to hear her avow it in a reluctant whisper! That was the view that war made mothers take of the chief blessing they could ask for their children! Campton understood her, and took the same view. George’s wonderful recovery, the one joy his parents had shared in the last twenty years, was now a misfortune to be denied and dissembled. They looked at each other like accomplices, the same thought in their eyes: if only the boy had been born in America! It was grotesque that the whole of joy or anguish should suddenly be found to hang on a geographical accident.

“After all, we’re Americans; this is not our job—” Campton began.

“No—” He saw she was waiting, and knew for what.

“So of course—if there were any trouble—but there won’t be; if there were, though, I shouldn’t hesitate to do what was necessary ... use any influence....”

“Oh, then we agree!” broke from her in a cry of wonder.

The unconscious irony of the exclamation struck him, and increased his irritation. He remembered the tone—undefinably compassionate—in which Dastrey had said: “I perfectly understand a foreigner’s taking that view”.... But was he a foreigner, Campton asked himself? And what was the criterion of citizenship, if he, who owed to France everything that had made life worth while, could regard himself as owing her nothing, now that for the first time he might have something to give her? Well, for himself that argument was all right: preposterous as he thought war—any war—he would have offered himself to France on the instant if she had had any use for his lame carcass. But he had never bargained to give her his only son.

Mrs. Brant went on in excited argument.

“Of course you know how careful I always am to do nothing about him without consulting you; but since you feel about it as we do——” She blushed under her faint rouge. The “we” had slipped out accidentally, and Campton, aware of turning hard-lipped and grim, sat waiting for her to repair the blunder. Through the years of his poverty it had been impossible not to put up, on occasions, with that odious first person plural: as long as his wretched inability to make money had made it necessary that his wife’s second husband should pay for his son’s keep, such allusions had been part of Campton’s long expiation. But even then he had tacitly made his former wife understand that, when they had to talk of the boy, he could bear her saying “I think,” or “Anderson thinks,” this or that, but not “we think it.” And in the last few years, since Campton’s unforeseen success had put him, to the astonishment of every one concerned, in a position of financial independence, “Anderson” had almost entirely dropped out of their talk about George’s future. Mrs. Brant was not a clever woman, but she had a social adroitness that sometimes took the place of intelligence.

On this occasion she saw her mistake so quickly, and blushed for it so painfully, that at any other time Campton would have smiled away her distress; but at the moment he could not stir a muscle to help her.

“Look here,” he broke out, “there are things I’ve had to accept in the past, and shall have to accept in the future. The boy is to go into Bullard and Brant’s—it’s agreed; I’m not sure enough of being able to provide for him for the next few years to interfere with—with your plans in that respect. But I thought it was understood once for all——”

She interrupted him excitedly. “Oh, of course ... of course. You must admit I’ve always respected your feeling....”

He acknowledged awkwardly: “Yes.”

“Well, then—won’t you see that this situation is different, terribly different, and that we ought all to work together? If Anderson’s influence can be of use....”

“Anderson’s influence——” Campton’s gorge rose against the phrase! It was always Anderson’s influence that had been invoked—and none knew better than Campton himself how justly—when the boy’s future was under discussion. But in this particular case the suggestion was intolerable.

“Of course,” he interrupted drily. “But, as it happens, I think I can attend to this job myself.”

She looked down at her huge rings, hesitated visibly, and then flung tact to the winds. “What makes you think so? You don’t know the right sort of people.”

It was a long time since she had thrown that at him: not since the troubled days of their marriage, when it had been the cruellest taunt she could think of. Now it struck him simply as a particularly unpalatable truth. No, he didn’t know “the right sort of people” ... unless, for instance, among his new patrons, such a man as Jorgenstein answered to the description. But, if there were war, on what side would a cosmopolitan like Jorgenstein turn out to be?

“Anderson, you see,” she persisted, losing sight of everything in the need to lull her fears, “Anderson knows all the political people. In a business way, of course, a big banker has to. If there’s really any chance of George’s being taken you’ve no right to refuse Anderson’s help—none whatever!”

Campton was silent. He had meant to reassure her, to reaffirm his conviction that the boy was sure to be discharged. But as their eyes met he saw that she believed this no more than he did; and he felt the contagion of her incredulity.

“But if you’re so sure there’s not going to be war——” he began.

As he spoke he saw her face change, and was aware that the door behind him had opened and that a short man, bald and slim, was advancing at a sort of mincing trot across the pompous garlands of the Savonnerie carpet. Campton got to his feet. He had expected Anderson Brant to stop at sight of him, mumble a greeting, and then back out of the room—as usual. But Anderson Brant did nothing of the sort: he merely hastened his trot toward the tea-table. He made no attempt to shake hands with Campton, but bowing shyly and stiffly said: “I understood you were coming, and hurried back ... on the chance ... to consult....”

Campton gazed at him without speaking. They had not seen each other since the extraordinary occasion, two years before, when Mr. Brant, furtively one day at dusk, had come to his studio to offer to buy George’s portrait; and, as their eyes met, the memory of that visit reddened both their faces.

Mr. Brant was a compact little man of about sixty. His sandy hair, just turning grey, was brushed forward over a baldness which was ivory-white at the crown and became brick-pink above the temples, before merging into the tanned and freckled surface of his face. He was always dressed in carefully cut clothes of a discreet grey, with a tie to match, in which even the plump pearl was grey, so that he reminded Campton of a dry perpendicular insect in protective tints; and the fancy was encouraged by his cautious manner, and the way he had of peering over his glasses as if they were part of his armour. His feet were small and pointed, and seemed to be made of patent leather; and shaking hands with him was like clasping a bunch of twigs.

It had been Campton’s lot, on the rare occasions of his meeting Mr. Brant, always to see this perfectly balanced man in moments of disequilibrium, when the attempt to simulate poise probably made him more rigid than nature had created him. But to-day his perturbation betrayed itself in the gesture with which he drummed out a tune on the back of the gold and platinum cigar-case he had unconsciously drawn from his pocket.

After a moment he seemed to become aware of what he had in his hand, and pressing the sapphire spring held out the case with the remark: “Coronas.”

Campton made a movement of refusal, and Mr. Brant, overwhelmed, thrust the cigar-case away.

“I ought to have taken one—I may need him,” Campton thought; and Mrs. Brant said, addressing her husband: “He thinks as we do—exactly.”

Campton winced. Thinking as the Brants did was, at all times, so foreign to his nature and his principles that his first impulse was to protest. But the sight of Mr. Brant, standing there helplessly, and trying to hide the twitching of his lip by stroking his lavender-scented moustache with a discreetly curved hand, moved the painter’s imagination.

“Poor devil—he’d give all his millions if the boy were safe,” he thought, “and he doesn’t even dare to say so.”

It satisfied Campton’s sense of his rights that these two powerful people were hanging on his decision like frightened children, and he answered, looking at Mrs. Brant: “There’s nothing to be done at present ... absolutely nothing—— Except,” he added abruptly, “to take care not to talk in this way to George.”

Mrs. Brant lifted a startled gaze.

“What do you mean? If war is declared, you can’t expect me not to speak of it to him.”

“Speak of it as much as you like, but don’t drag him in. Let him work out his own case for himself.”

He went on with an effort: “It’s what I intend to do.”

“But you said you’d use every influence!” she protested, obtusely.

“Well—I believe this is one of them.”

She looked down resignedly at her clasped hands, and he saw her lips tighten. “My telling her that has been just enough to start her on the other tack,” he groaned to himself, all her old stupidities rising up around him like a fog.

Mr. Brant gave a slight cough and removed his protecting hand from his lips.

“Mr. Campton is right,” he said, quickly and timorously. “I take the same view—entirely. George must not know that we are thinking of using ... any means....” He coughed again, and groped for the cigar-case.

As he spoke, there came over Campton a sense of their possessing a common ground of understanding that Campton had never found in his wife. He had had a hint of the same feeling, but had voluntarily stifled it, on the day when Mr. Brant, apologetic yet determined, had come to the studio to buy George’s portrait. Campton had seen then how the man suffered from his failure, but had chosen to attribute his distress to the humiliation of finding there were things his money could not purchase. Now, that judgment seemed as unimaginative as he had once thought Mr. Brant’s overture. Campton turned on the banker a look that was almost brotherly.

“We men know ...” the look said; and Mr. Brant’s parched cheek was suffused with a flush of understanding. Then, as if frightened at the consequences of such complicity, he repeated his bow and went out.

When Campton issued forth into the Avenue Marigny, it came to him as a surprise to see the old unheeding life of Paris still going on. In the golden decline of day the usual throng of idlers sat under the horse-chestnuts of the Champs Elysées, children scampered between turf and flowers, and the perpetual stream of motors rolled-up the central avenue to the restaurants beyond the gates.

Under the last trees of the Avenue Gabriel the painter stood looking across the Place de la Concorde. No doubt the future was dark: he had guessed from Mr. Brant’s precipitate arrival that the banks and the Stock Exchange feared the worst. But what could a man do, whose convictions were so largely formed by the play of things on his retina, when, in the setting sun, all that majesty of space and light and architecture was spread out before him undisturbed? Paris was too triumphant a fact not to argue down his fears. There she lay in the security of her beauty, and once more proclaimed herself eternal.

III

The night was so lovely that, though the Boulogne express arrived late, George at once proposed dining in the Bois.

His luggage, of which, as usual, there was a good deal, was dropped at the Crillon, and they shot up the Champs Elysées as the summer dusk began to be pricked by lamps.

“How jolly the old place smells!” George cried, breathing in the scent of sun-warmed asphalt, of flowerbeds and freshly-watered dust. He seemed as much alive to such impressions as if his first word at the station had not been: “Well, this time I suppose we’re in for it.” In for it they might be; but meanwhile he meant to enjoy the scents and scenes of Paris as acutely and unconcernedly as ever.

Campton had hoped that he would pick out one of the humble cyclists’ restaurants near the Seine; but not he. “Madrid, is it?” he said gaily, as the taxi turned into the Bois; and there they sat under the illuminated trees, in the general glitter and expensiveness, with the Tziganes playing down their talk, and all around them the painted faces that seemed to the father so old and obvious, and to the son, no doubt, so full of novelty and mystery.

The music made conversation difficult; but Campton did not care. It was enough to sit and watch the face in which, after each absence, he noted a new and richer vivacity. He had often tried to make up his mind if his boy were handsome. Not that the father’s eye influenced the painter’s; but George’s young head, with its thick blond thatch, the complexion ruddy to the golden eyebrows, and then abruptly white on the forehead, the short amused nose, the inquisitive eyes, the ears lying back flat to the skull against curly edges of fair hair, defied all rules and escaped all classifications by a mixture of romantic gaiety and shrewd plainness like that in certain eighteenth-century portraits.

As father and son faced each other over the piled-up peaches, while the last sparkle of champagne died down in their glasses, Campton’s thoughts went back to the day when he had first discovered his son. George was a schoolboy of twelve, at home for the Christmas holidays. At home meant at the Brants’, since it was always there he stayed: his father saw him only on certain days. Usually Mariette fetched him to the studio on one afternoon in the week; but this particular week George was ill, and it had been arranged that in case of illness his father was to visit him at his mother’s. He had one of his frequent bad colds, and Campton recalled him, propped up in bed in his luxurious overheated room, a scarlet sweater over his nightshirt, a book on his thin knees, and his ugly little fever-flushed face bent over it in profound absorption. Till that moment George had never seemed to care for books: his father had resigned himself to the probability of seeing him grow up into the ordinary pleasant young fellow, with his mother’s worldly tastes. But the boy was reading as only a bookworm reads—reading with his very finger-tips, and his inquisitive nose, and the perpetual dart ahead of a gaze that seemed to guess each phrase from its last word. He looked up with a smile, and said: “Oh, Dad ...” but it was clear that he regarded the visit as an interruption. Campton, leaning over, saw that the book was a first edition of Lavengro.

“Where the deuce did you get that?”

George looked at him with shining eyes. “Didn’t you know? Mr. Brant has started collecting first editions. There’s a chap who comes over from London with things for him. He lets me have them to look at when I’m seedy. I say, isn’t this topping? Do you remember the fight?” And, marvelling once more at the ways of Providence, Campton perceived that the millionaire’s taste for owning books had awakened in his stepson a taste for reading them. “I couldn’t have done that for him,” the father had reflected with secret bitterness. It was not that a bibliophile’s library was necessary to develop a taste for letters; but that Campton himself, being a small reader, had few books about him, and usually borrowed those few. If George had lived with him he might never have guessed the boy’s latent hunger, for the need of books as part of one’s daily food would scarcely have presented itself to him.

From that day he and George had understood each other. Initiation had come to them in different ways, but their ardour for beauty had the same root. The visible world, and its transposition in terms of one art or another, were thereafter the subject of their interminable talks; and Campton, with a passionate interest, watched his son absorbing through books what had mysteriously reached him through his paintbrush.

They had been parted often, and for long periods; first by George’s schooling in England, next by his French military service, begun at eighteen to facilitate his entry into Harvard; finally, by his sojourn at the University. But whenever they were together they seemed to make up in the first ten minutes for the longest separation; and since George had come of age, and been his own master, he had given his father every moment he could spare.

His career at Harvard had been interrupted, after two years, by the symptoms of tuberculosis which had necessitated his being hurried off to the Engadine. He had returned completely cured, and at his own wish had gone back to Harvard; and having finished his course and taken his degree, he had now come out to join his father on a long holiday before entering the New York banking-house of Bullard and Brant.

Campton, looking at the boy’s bright head across the lights and flowers, thought how incredibly stupid it was to sacrifice an hour of such a life to the routine of money-getting; but he had had that question out with himself once for all, and was not going to return to it. His own success, if it lasted, would eventually help him to make George independent; but meanwhile he had no right to interfere with the boy’s business training. He had hoped that George would develop some marked talent, some irresistible tendency which would decide his future too definitely for interference; but George was twenty-five, and no such call had come to him. Apparently he was fated to be only a delighted spectator and commentator; to enjoy and interpret, not to create. And Campton knew that this absence of a special bent, with the strain and absorption it implies, gave the boy his peculiar charm. The trouble was that it made him the prey of other people’s plans for him. And now all these plans—Campton’s dreams for the future as well as the business arrangements which were Mr. Brant’s contribution—might be wrecked by to-morrow’s news from Berlin. The possibility still seemed unthinkable; but in spite of his incredulity the evil shadow hung on him as he and his son chatted of political issues.

George made no allusion to his own case: his whole attitude was so dispassionate that his father began to wonder if he had not solved the question by concluding that he would not pass the medical examination. The tone he took was that the whole affair, from the point of view of twentieth-century civilization, was too monstrous an incongruity for something not to put a stop to it at the eleventh hour. His easy optimism at first stimulated his father, and then began to jar on him.

“Dastrey doesn’t think it can be stopped,” Campton said at length.

The boy smiled.

“Dear old Dastrey! No, I suppose not. That after-Sedan generation have got the inevitability of war in their bones. They’ve never been able to get beyond it. Our whole view is different: we’re internationals, whether we want to be or not.”

“To begin with, if by ‘our’ view you mean yours and mine, you and I haven’t a drop of French blood in us,” his father interposed, “and we can never really know what the French feel on such matters.”

George looked at him affectionately. “Oh, but I didn’t—I meant ‘we’ in the sense of my generation, of whatever nationality. I know French chaps who feel as I do—Louis Dastrey, Paul’s nephew, for one; and lots of English ones. They don’t believe the world will ever stand for another war. It’s too stupidly uneconomic, to begin with: I suppose you’ve read Angell? Then life’s worth too much, and nowadays too many millions of people know it. That’s the way we all feel. Think of everything that counts—art and science and poetry, and all the rest—going to smash at the nod of some doddering diplomatist! It was different in old times, when the best of life, for the immense majority, was never anything but plague, pestilence and famine. People are too healthy and well-fed now; they’re not going off to die in a ditch to oblige anybody.”

Campton looked away, and his eye, straying over the crowd, lit on the long heavy face of Fortin-Lescluze, seated with a group of men on the other side of the garden.

Why had it never occurred to him before that if there was one being in the world who could get George discharged it was the great specialist under whose care he had been?

“Suppose war does come,” the father thought, “what if I were to go over and tell him I’ll paint his dancer?” He stood up and made his way between the tables.

Fortin-Lescluze was dining with a party of jaded-looking politicians and journalists. To reach him Campton had to squeeze past another table, at which a fair worn-looking lady sat beside a handsome old man with a dazzling mane of white hair and a Grand Officer’s rosette of the Legion of Honour. Campton bowed, and the lady whispered something to her companion, who returned a stately vacant salute. Poor old Beausite, dining alone with his much-wronged and all-forgiving wife, bowing to the people she told him to bow to, and placidly murmuring: “War—war,” as he stuck his fork into the peach she had peeled!

At Fortin’s table the faces were less placid. The men greeted Campton with a deference which was not lost on Mme. Beausite, and the painter bent close over Fortin, embarrassed at the idea that she might overhear him. “If I can make time for a sketch—will you bring your dancing lady to-morrow?”

The physician’s eyes lit up under their puffy lids.

“My dear friend—will I? She’s simply set her heart on it!” He drew out his watch and added: “But why not tell her the good news yourself? You told me, I think, you’d never seen her? This is her last night at the ‘Posada,’ and if you’ll jump into my motor we shall be just in time to see her come on.”

Campton beckoned to George, and father and son followed Fortin-Lescluze. None of the three men, on the way back to Paris, made any reference to the war. The physician asked George a few medical questions, and complimented him on his look of recovered health; then the talk strayed to studios and theatres, where Fortin-Lescluze firmly kept it.

The last faint rumours of the conflict died out on the threshold of the “Posada.” It would have been hard to discern, in the crowded audience, any appearance but that of ordinary pleasure-seekers momentarily stirred by a new sensation. Collectively, fashionable Paris was already away, at the seashore or in the mountains, but not a few of its chief ornaments still lingered, as the procession through Campton’s studio had proved; and others had returned drawn back by doubts about the future, the desire to be nearer the source of news, the irresistible French craving for the forum and the market when messengers are foaming in. The public of the “Posada,” therefore, was still Parisian enough to flatter the new dancer; and on all the pleasure-tired faces, belonging to every type of money-getters and amusement-seekers, Campton saw only the old familiar music-hall look: the look of a house with lights blazing and windows wide, but nobody and nothing within.

The usualness of it all gave him a sense of ease which his boy’s enjoyment confirmed. George, lounging on the edge of their box, and watching the yellow dancer with a clear-eyed interest refreshingly different from Fortin’s tarnished gaze, George so fresh and cool and unafraid, seemed to prove that a world which could produce such youths would never again settle its differences by the bloody madness of war.

Gradually Campton became absorbed in the dancer and began to observe her with the concentration he brought to bear on any subject that attracted his brush. He saw that she was more paintable than he could have hoped, though not in the extravagant dress and attitude he was sure her eminent admirer would prefer; but rather as a little crouching animal against a sun-baked wall. He smiled at the struggle he should have when the question of costume came up.

“Well, I’ll do her, if you like,” he turned to say; and two tears of senile triumph glittered on the physician’s cheeks.

“To-morrow, then—at two—may I bring her? She leaves as soon as possible for the south. She lives on sun, heat, radiance....”

“To-morrow—yes,” Campton nodded.

His decision once reached, the whole subject bored him, and in spite of Fortin’s entreaties he got up and signalled to George.

As they strolled home through the brilliant midnight streets, the boy said: “Did I hear you tell old Fortin you were going to do his dancer?”

“Yes—why not? She’s very paintable,” said Campton, abruptly shaken out of his security.

“Beginning to-morrow?”

“Why not?”

“Come, you know—to-morrow!” George laughed.

“We’ll see,” his father rejoined, with an obscure sense that if he went on steadily enough doing his usual job it might somehow divert the current of events.

On the threshold of the hotel they were waylaid by an elderly man with a round face and round eyes behind gold eye-glasses. His grey hair was cut in a fringe over his guileless forehead, and he was dressed in expensive evening clothes, and shone with soap and shaving; but the anxiety of a frightened child puckered his innocent brow and twitching cheeks.

“My dear Campton—the very man I’ve been hunting for! You remember me—your cousin Harvey Mayhew of Utica?”

Campton, with an effort, remembered, and asked what he could do, inwardly hoping it was not a portrait.

“Oh, the simplest thing in the world. You see, I’m here as a Delegate——” At Campton’s look of enquiry, Mr. Mayhew interrupted himself to explain: “To the Peace Congress at The Hague——why, yes: naturally. I landed only this morning, and find myself in the middle of all this rather foolish excitement, and unable to make out just how I can reach my destination. My time is—er—valuable, and it is very unfortunate that all this commotion should be allowed to interfere with our work. It would be most annoying if, after having made the effort to break away from Utica, I should arrive too late for the opening of the Congress.”

Campton looked at him wonderingly. “Then you’re going anyhow?”

“Going? Why not? You surely don’t think——?” Mr. Mayhew threw back his shoulders, pink and impressive. “I shouldn’t, in any case, allow anything so opposed to my convictions as war to interfere with my carrying out my mandate. All I want is to find out the route least likely to be closed if—if this monstrous thing should happen.”

Campton considered. “Well, if I were you, I should go round by Luxembourg—it’s longer, but you’ll be out of the way of trouble.” He gave a nod of encouragement, and the Peace Delegate thanked him profusely.

Father and son were lodged on the top floor of the Crillon, in the little apartment which opens on the broad terraced roof. Campton had wanted to put before his boy one of the city’s most perfect scenes; and when they reached their sitting-room George went straight out onto the terrace, and leaning on the parapet, called back: “Oh, don’t go to bed yet—it’s too jolly.”

Campton followed, and the two stood looking down on the festal expanse of the Place de la Concorde strown with great flower-clusters of lights between its pearly distances. The sky was full of stars, pale, remote, half-drowned in the city’s vast illumination; and the foliage of the Champs Elysées and the Tuileries made masses of mysterious darkness behind the statues and the flashing fountains.

For a long time neither father nor son spoke; then Campton said: “Are you game to start the day after to-morrow?”

George waited a moment. “For Africa?”

“Well—my idea would be to push straight through to the south—as far as Palermo, say. All this cloudy watery loveliness gives me a furious appetite for violent red earth and white houses crackling in the glare.”

George again pondered; then he said: “It sounds first-rate. But if you’re so sure we’re going to start why did you tell Fortin to bring that girl to-morrow?”

Campton, reddening in the darkness, felt as if his son’s clear eyes were following the motions of his blood. Had George suspected why he had wanted to ingratiate himself with the physician?

“It was stupid—I’ll put her off,” he muttered. He dropped into an armchair, and sat there, in his clumsy infirm attitude, his arms folded behind his head, while George continued to lean on the parapet.

The boy’s question had put an end to their talk by baring the throbbing nerve of his father’s anxiety. If war were declared the next day, what did George mean to do? There was every hope of his obtaining his discharge; but would he lend himself to the attempt? The deadly fear of crystallizing his son’s refusal by forcing him to put it into words kept Campton from asking the question.