Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

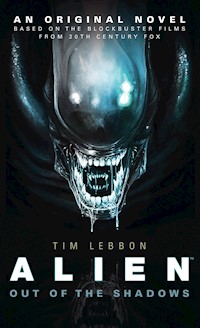

- Serie: Alien

- Sprache: Englisch

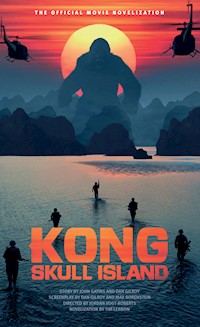

The official new novel set between the events of Alien and Aliens An original novel based on the blockbuster films from 20th Century Fox Out Of The Shadows As a child, Chris Hooper dreamed of monsters. But in deep space, he found only darkness and isolation. Then on planet LV178, he and his fellow miners discovered a storm-scoured, sand-blasted hell—and trimonite, the hardest material known to man. When a shuttle crashes into the mining ship Marion, the miners learn that there was more than trimonite deep in the caverns. there was evil, hibernating—and waiting for suitable prey. Hoop and his associates uncover a nest of Xenomorphs, and hell takes on new meaning. Quickly they discover that their only hope lies with the unlikeliest of saviors... Ellen Ripley, the last human survivor of the salvage ship Nostromo.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

ALIEN™: SEA OF SORROWS (JULY 2014)

THE OFFICIAL MOVIE NOVELIZATIONS

ALIEN (MARCH 2014)

ALIENS™ (APRIL 2014)

ALIEN3 (MAY 2014)

ALIEN

OUT OF THE SHADOWS

TIM LEBBON

TITAN BOOKS

ALIEN™: OUT OF THE SHADOWS

Print edition ISBN: 9781781162682

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781162699

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: January 2014

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2014 by Tim Lebbon. All rights reserved.

Alien ™ & © 2014 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website

www.titanbooks.com

Contents

Epigraph

Yearly Progress Report

Part 1: Dreaming of Monsters

1: Marion

2: Samson

3: Ripley

4: 937

5: Narcissus

6: Family

7: Shadows

8: Vacuum

9: Drop

Part 2: Underground

10: Skin

11: Mine

12: Cattle

13: Aliens

14: Builders

15: Offspring

16: Majesty

17: Ancients

18: Elevator

19: Cells

Part 3: Nothing Good

20: Home

21: Pain

22: Chess

23: Forgetting

24: Revenge

25: Gone

About the Author

“The universe seems neither benignnor hostile, merely indifferent.”

CARL SAGAN

YEARLY PROGRESS REPORT:

To: Weyland-Yutani Corporation, Science Division

(Ref: code 937)

Date (unspecified)

Transmission (pending)

My search continues.

PART 1

DREAMING OF MONSTERS

1

MARION

Chris Hooper dreamed of monsters.

As a youngster they’d fascinated him, as they did all children. But unlike children born generations before him, there were places he could go, destinations he could explore, where he might just find them. No longer restricted to the pages of fairy tales or the digital imagery of imaginative moviemakers, humankind’s forays into space had opened up a whole galaxy of possibilities.

So from a young age he looked to the stars, and those dreams persisted.

In his early twenties he’d worked for a year on Callisto, one of Jupiter’s moons. They’d been hauling ores from several miles below the surface, and in a nearby mine a Chinese team had broken through into a sub-surface sea. There had been crustaceans and shrimp, tiny pilot fish and delicate frond-like creatures a hundred feet long. But no monsters to set his imagination on fire.

When he’d left the solar system to work in deep space, traveling as engineer on various haulage, exploration, and mining ships, he’d eagerly sought out tales of alien life forms encountered on those distant asteroids, planets, and moons. Though adulthood had diluted his youngster’s vivid imagination with more mundane concerns—family estrangement, income, and well-being—he still told himself stories. But over the years, none of what he’d found had lived up to the fictions he’d created.

As time passed he’d come to terms with the fact that monsters were only monsters before they were found, and perhaps the universe wasn’t quite so remarkable as he’d once hoped.

Certainly not here.

Working in one of the Marion’s four docking bays, he paused to look down at the planet below with a mixture of distaste and boredom. LV178. Such an inhospitable, storm-scoured, sand-blasted hell of a rock that they hadn’t even bothered to give it a proper name. He’d spent three long years here, making lots of money he had no opportunity to spend.

Trimonite was the hardest, strongest material known to man, and when a seam as rich as this one was found, it paid to mine it out. One day he’d head home, he promised himself at the end of every fifty-day shift. Home to the two boys and wife he’d run away from seven years before. One day. But he was beginning to fear that this life had become a habit, and the longer it continued, the harder it might be to break.

“Hoop!” The voice startled him, and as he spun around Jordan was already chuckling.

He and the captain had been involved briefly, a year before. These confined quarters and stressful work conditions meant that such liaisons were frequent, and inevitably brief. But Hoop liked the fact that they had remained close. Once they’d got the screwing out of the way, they’d become the best of friends.

“Lucy, you scared the shit out of me.”

“That’s Captain Jordan to you.” She examined the machinery he’d been working on, without even glancing at the viewing window. “All good here?”

“Yeah, heat baffles need replacing, but I’ll get Powell and Welford onto that.”

“The terrible twins,” Jordan said, smiling. Powell was close to six foot six, tall, black, and slim as a pole. Welford was more than a foot shorter, white, and twice as heavy. As different as could be, yet the ship’s engineers were both smartasses.

“Still no contact?” Hoop asked.

Jordan frowned briefly. It wasn’t unusual to lose touch with the surface, but not for two days running.

“Storms down there are the worst I’ve seen,” she said, nodding at the window. From three hundred miles up, the planet’s surface looked even more inhospitable than usual—a smear of burnt oranges and yellows, browns and blood-reds, with the circling eyes of countless sandstorms raging across the equatorial regions. “They’ve gotta abate soon. I’m not too worried yet, but I’ll be happy when we can talk to the dropships again.”

“Yeah, you and me both. The Marion feels like a derelict when we’re between shifts.”

Jordan nodded. She was obviously concerned, and for an awkward, silent moment Hoop thought he should say something more to comfort her. But she was the captain because she could handle situations like this. That, and because she was a badass.

“Lachance is doing spaghetti again tonight,” she said.

“For a Frenchman, he sure can cook Italian.”

Jordan chuckled, but he could feel her tension.

“Lucy, it’s just the storms,” Hoop said. He was sure of that. But he was equally sure that “just storms” could easily cause disaster. Out here in the furthest quadrants of known space—pushing the limits of technology, knowledge, and understanding, and doing their best to deal with the corners cut by the Kelland Mining Company—it didn’t take much for things to go wrong.

Hoop had never met a ship’s engineer better than him, and that was why he was here. Jordan was an experienced flight captain, knowledgeable and wise. Lachance, cynical and gruff, was an excellent pilot who had a healthy respect for space and all it could throw at them. And the rest of their team, though a mixed bunch, were all more than capable at their jobs. The miners themselves were a hardy breed, many of them experienced from stints on Jupiter’s and Neptune’s moons. Mean bastards, with streaks of sick humor, most were as hard as the trimonite they sought.

But no experience, no confidence or hardness or pig-headedness, could dodge fate. They all knew how dangerous it was. Most of them had grown used to living with the danger, and the close proximity of death.

Only seven months ago they’d lost three miners in an accident in Bay One as the dropship Samson came in to dock. No one’s fault, really. Just eagerness to be back on board in relative comfort, after fifty days down the mine. The airlock hadn’t sealed properly, an indicator had malfunctioned, and the two men and a woman had suffocated.

Hoop knew that Jordan still had sleepless nights over that. For three days after transmitting her condolences to the miners’ families, she hadn’t left her cabin. As far as Hoop was concerned, that was what made her a great captain—she was a badass who cared.

“Just the storms,” she echoed. She leaned past Hoop and rested against the bulkhead, looking down through the window. Despite the violence, from up here the planet looked almost beautiful, an artist’s palette of autumnal colors. “I fucking hate this place.”

“Pays the bills.”

“Ha! Bills...” She seemed in a maudlin mood, and Hoop didn’t like her like this. Perhaps that was a price of their closeness—he got to see a side of her the rest of the crew never would.

“Almost finished,” he said, nudging some loose ducting with his foot. “Meet you in the rec room in an hour. Shoot some pool?”

Jordan raised an eyebrow. “Another rematch?”

“You’ve got to let me win sometime.”

“You’ve never, ever beaten me at pool.”

“But I used to let you play with my cue.”

“As your captain, I could put you in the brig for such comments.”

“Yeah. Right. You and which army?”

Jordan turned her back on Hoop. “Stop wasting time and get back to work, chief engineer.”

“Yes, captain.” He watched her walk away along the dusky corridor and through a sliding door, and then he was alone again.

Alone with the atmosphere, the sounds, the smells of the ship...

The stench of space-flea piss from the small, annoying mites that managed to multiply, however many times the crew tried to purge them. They were tiny, but a million fleas pissing produced a sharp, rank odor that clung to the air.

The constant background hum of machinery was inaudible unless Hoop really listened for it, because it was so ever-present. There were distant thuds, echoing grinds, the whisper of air movement encouraged by conditioning fans and baffles, the occasional creak of the ship’s huge bulk settling and shifting. Some of the noises he could identify because he knew them so well, and on occasion he perceived problems simply through hearing or not hearing them—sticking doors, worn bearings in air duct seals, faulty transmissions.

But there were also mysterious sounds that vibrated through the ship now and then, like hesitant, heavy footsteps in distant corridors, or someone screaming from a level or two away. He’d never figured those out. Lachance liked to say it was the ship screaming in boredom.

He hoped that was all they were.

The vessel was huge and would take him half an hour to walk from nose to tail, and yet it was a speck in the vastness of space. The void exerted a negative pressure on him, and if he thought about it too much, he thought he would explode—be ripped apart, cell by cell, molecule by molecule, spread to the cosmos from which he had originally come. He was the stuff of the stars, and when he was a young boy—dreaming of monsters, and looking to space in the hope that he would find them—that had made him feel special.

Now, it only made him feel small.

However close they all lived together on the Marion, they were alone out here.

Shaking away the thoughts, he bent to work again, making more noise than was necessary—a clatter to keep him company. He was looking forward to shooting some pool with Jordan and having her whip his ass again. There were colleagues and acquaintances aplenty, but she was the closest thing he had to a good friend.

* * *

The recreation room was actually a block of four compartments to the rear of the Marion’s accommodations hub. There was a movie theater with a large screen and an array of seating, a music library with various listening posts, a reading room with comfortable chairs and reading devices—and then there was Baxter’s Bar, better known as BeeBee’s. Josh Baxter was the ship’s communications officer, but he also acted as their barman. He mixed a mean cocktail.

Though it was sandwiched back between the accommodations hub and the sectioned holds, BeeBee’s was the social center of the ship. There were two pool tables, table tennis, a selection of faux-antique computer game consoles, and the bar area with tables and chairs scattered in casual abandon. It had not been viewed as a priority by the company that paid the ship’s designers, so the ceiling was a mass of exposed service pipework, the floor textured metal, the walls bare and unpainted. However, those using BeeBee’s had done their best to make it more comfortable. Seats were padded, lighting was low and moody, and many miners and crew had copied Baxter’s idea of hanging decorated blankets from the walls. Some painted the blankets, others tore and tied. Each of them was distinct. It gave the whole rec room a casual, almost arty air.

Miners had fifty days between shifts on the planet, so they often spent much of their off-time here, and though alcohol distribution was strictly regulated, it still made for some raucous nights.

Captain Jordan allowed that. In fact, she positively encouraged it, because it was a release of tension that the ship would otherwise barely contain. It wasn’t possible to communicate with any of their loved ones back home. Distances were so vast, time so extended, that any meaningful contact was impossible. They needed somewhere to feel at home, and BeeBee’s provided just that.

When Hoop entered, it was all but deserted. These quiet times between shift changes gave Baxter time to clear out the bar stock, tidy the room, and prepare for the next onslaught. He worked quietly behind the bar, stocking bottled beer and preparing a selection of dehydrated snacks. Water on the ship always tasted vaguely metallic, so he rehydrated many of the treats in stale beer. No one complained.

“And here he is,” Jordan said. She was sitting on a stool by one of the pool tables, bottle in hand. “Back for another beating. What do you think, Baxter?”

Baxter nodded a greeting to Hoop.

“Sucker for punishment,” he agreed.

“Yep. Sucker.”

“Well if you don’t want to play...” Hoop said.

Jordan slid from her stool, plucked a cue from the rack and lobbed it at him. As he caught it out of the air, the ship’s intercom chimed.

“Oh, now, what the hell?” Jordan sighed.

Baxter leaned across the bar and hit the intercom.

“Captain! Anyone!” It was their pilot, Lachance. “Get up to the bridge, now. We’ve got incoming from one of the dropships.” His French accent was much more acute than normal. That happened when he was upset or stressed, neither of which occurred very often.

Jordan dashed to the bar and pressed the transmit button.

“Which one?”

“The Samson. But it’s fucked up.”

“What do you mean?” In the background, behind Lachance’s confused words and the sounds of chaos from the bridge, Hoop heard static-tinged screaming. He and Jordan locked eyes.

Then they ran, and Baxter followed.

* * *

The Marion was a big ship, far more suited to massive deep-ore mining than trimonite extrusion, and it took them a few minutes to make their way to the bridge. Along the curved corridor that wound around the accommodations hub, then up three levels by elevator. By the time they bumped into Garcia and Kasyanov, everyone else was there.

“What’s going on?” Jordan demanded. Baxter rushed across to the communications center, and Lachance stood gratefully to vacate his chair. Baxter slipped on a pair of headphones, and his left hand hovered over an array of dials and switches.

“Heard something coming through static a few minutes ago,” Lachance said. “The higher they climb, the clearer it gets.” They called him “No-Chance” Lachance because of his laconic pessimism, but in truth he was one of the most level-headed among them. Now, Hoop could see by his expression that something had him very rattled.

From loudspeakers around the bridge, frantic breathing crackled.

“Samson, Captain Jordan is now on the bridge,” Baxter said. “Please give us your—”

“I don’t have time to fucking give you anything, just get the med pods fired up!” The voice was so distorted that they couldn’t tell who it was.

Jordan grabbed a headset from beside Baxter. Hoop looked around at the others, all of them standing around the communications area. The bridge was large, but they were all bunched in close. They showed the tension they had to be feeling, even the usually unflappable science officer, Karen Sneddon. The thin, severe-faced woman had been to more planets, asteroids, and moons than all of them put together. But there was fear in her eyes.

“Samson, this is Captain Jordan. What’s happening? What’s going on down at the mine?”

“... creatures! We’ve—”

The contact cut out abruptly, leaving the bridge ringingly silent.

Wide viewing windows looked out onto the familiar view of space and an arc of the planet below, as if nothing had changed. The low-level hum of machinery was complemented by agitated breathing.

“Baxter,” Jordan said softly, “I’d like them back online.”

“I’m doing my best,” he replied.

“Creatures?” The ship’s medic Garcia tapped nervously at her chin. “No one’s ever seen creatures down the mine, have they?”

“There’s nothing living on that rock, other than bacteria,” Sneddon said. She was shifting from foot to foot. “Maybe that’s not what they said. Maybe they said fissures, or something.”

“Have we got them on scanner yet?” Jordan asked.

Baxter waved to his left, where three screens were set aslant in the control panel. One was backlit a dull green, and it showed two small points of light moving quickly toward them. Interference from electrical storms in the upper atmosphere sparked across the screen. But the points were firm, their movement defined.

“Which is the Samson?” Hoop asked.

“Lead ship is Samson,” Lachance said. “The Delilah follows.”

“Maybe ten minutes out,” Jordan said. “Any communication from Delilah?”

No one answered. Answer enough.

“I’m not sure we can—” Hoop began, then the speakers burst back into life. Let them dock, he was going to say.

“—stuck to their faces!” the voice said. It was still unrecognizable.

Baxter turned some dials, and then a larger screen above his station flickered to life. The Samson’s pilot, Vic Jones, appeared as a blurred image. Hoop tried to see past him to the inner cabin of the dropship, but the vibration of their steep ascent out of LV178’s atmosphere made a mess out of everything.

“How many with you?” Hoop asked.

“Hoop? That you?”

“Yeah.”

“The other shift found something. Something horrible. Few of them... ” He faded out again, his image stuttering and flickering as atmospherics caused more chaos.

“Kasyanov, you and Garcia get to sick bay and fire up the med pods,” Jordan said to the doctor and her medic.

“You can’t be serious,” Hoop said. As Jordan turned on him, Jones’s voice crackled in again.

“—all four, only me and Sticky untouched. They’re okay right now, but... to shiver and spit. Just get... to dock!”

“They might be infected!” Hoop said.

“Which is why we’ll get them straight to sick bay.”

“This is fucking serious.” Hoop nodded at the screen where Jones’s image continued to flicker and dance, his voice cutting in and out. Most of what Jones said made little sense, but they could all hear his terror. “He’s shitting himself!”

Kasyanov and Garcia hustled from the bridge, and Hoop looked to Sneddon for support. But the science officer was leaning over the back of Baxter’s chair, frowning as she tried to make out whatever else Jones was saying.

“Jones, what about the Delilah?” Jordan said into her headset. “Jones?”

“...left the same time... something got on board, and... ”

“What got on board?”

The screen snowed, the comm link fuzzed with static, and those remaining on the bridge stood staring at each other for a loaded, terrible few seconds.

“I’m getting down to the docking level,” Jordan said. “Cornell, with me. Baxter, tell them Bay Three.”

Hoop coughed a disbelieving laugh.

“You’re taking him to back you up?”

“He’s security officer, Hoop.”

“He’s a drunk!” Cornell didn’t even meet Hoop’s stare, let alone respond.

“He has a gun,” Jordan said. “You stay here, supervise the bridge. Lachance, help guide them in. Remote pilot the dropships if you have to.”

“If we can even get a link to them,” Lachance said.

“Assume we can, and do it!” Jordan snapped. She took a few deep breaths, and Hoop could almost hear her thoughts. Never figured it would fuck up this bad, gotta be calm, gotta be in control. He knew she was thinking about those three miners she’d lost, and dreading the idea of losing more. She looked straight at him. He frowned, but she turned and left the bridge before he could object again.

There was no way they should be letting the Samson dock, Hoop knew. Or if it did dock, they had to sever all external operation of the airlock until they knew it was safe. There had been twenty miners taken down to the surface, and twenty more scheduled to return in the dropships. Two shifts of twenty men and women—but right now, the ten people still on the Marion had to be the priority.

He moved to Baxter’s communication panel and checked the radar scanner again. The Samson had been tagged with its name now, and it looked to be performing a textbook approach, arcing up out of the atmosphere and approaching the orbiting Marion from the sunward side.

“Lachance?” Hoop asked, pointing at the screen.

“It’s climbing steeply. Jones is pushing it as hard and as fast as he can.”

“Keen to reach the Marion.”

“But that’s not right...” Lachance muttered.

“What?” Hoop asked.

“Delilah. She’s changing direction.”

“Baxter,” Hoop said, “plot a course trace on the Delilah.”

Baxter hit some buttons and the screen flickered as it changed. The Delilah grew a tail of blue dots, and its projected course appeared as a hazy fan.

“Who’s piloting Delilah this drop?”

“Gemma Keech,” Welford said. “She’s a good pilot.”

“Not today she isn’t. Baxter, we need to talk to Delilah, or see what’s happening on board.”

“I’m doing what I can.”

“Yeah.” Hoop had a lot of respect for Baxter. He was a strange guy, not really a mixer at all—probably why he spent more of his time behind the bar than in front of it—but he was a whiz when it came to communications tech. If things went wrong, he was their potential lifeline to home, and as such one of the most important people on the Marion.

“We have no idea what they’ve got on board,” Powell said. “Could be anything.”

“Did he say there’s only six of them on the Samson?” Welford asked. “What about all the others?”

Hoop shrugged. Each ship held twenty people and a pilot. If the Samson was returning less than half full—and they had no idea how many were on Delilah—then what had happened to the rest of them?

He closed his eyes briefly, trying to gather himself.

“I’ve got visual on Delilah!” Baxter said. He clicked a few more keys on his computer keyboard, then switched on one of the blank screens. “No audio, and there’s no response to my hails. Maybe...” But his voice trailed off.

They all saw what was happening inside Delilah.

The pilot, Gemma Keech, was screaming in her seat, terrified and determined, eyes glued to the window before her. It was haunting witnessing such fear in utter silence. Behind her, shadows thrashed and twisted.

“Baxter,” Hoop whispered. “Camera.”

Baxter stroked his keyboard and the view switched to a camera above and behind Keech’s head. It was a widescreen, compressing the image but taking in the entire passenger compartment.

And there was blood.

Three miners were kneeling directly behind the pilot. Two of them held spiked sand-picks, light alloy tools used for breaking through compacted sandstones. They were waving and lashing at something, but their target was just out of sight. The miner in the middle held a plasma torch.

“He can’t use that in there,” Powell said. “If he does he’ll... he’ll... what the fuck?”

Several miners seemed to have been strapped into their seats. Their heads were tilted back, chests a mess of blood and ripped clothing, protruding ribs and flesh. One of them still writhed and shook, and there was something coming out of her chest. Pulling itself out. A smooth curved surface glimmering with artificial light, it shone with her blood.

Other miners were splayed on the floor of the cabin, and seemed to be dead. Shapes darted between them, slicing and slashing, and blood was splashed across the floor, up the walls. It dripped from the ceiling.

At the back of the passenger cabin, three small shapes were charging again and again at a closed door. There was a small bathroom back there, Hoop knew, just two stalls and a washbasin. And there was something in there the things wanted.

Those things.

Each was the size of a small cat, and looked to be a deep ochre color, glittering with the wetness of their unnatural births. They were somehow sharp-looking, like giant beetles or scorpions back home.

The bathroom door was already heavily dented, and one side of it seemed to be caving in.

“That’s two inch steel,” Hoop said.

“We’ve got to help them,” Welford said.

“I think they’re beyond that,” Sneddon said, and for a moment Hoop wanted to punch her. But she was right. Keech’s silent screaming bore testament to that. Whatever else they had seen, whatever the pilot already knew, the hopelessness of the Delilah’s situation was evident in her eyes.

“Turn it off,” Hoop said, but Baxter could not comply. And all six of them on the bridge continued to watch.

The creatures smashed through the bathroom door and squeezed inside, and figures jerked and thrashed.

One of the miners holding a sand-pick flipped up and forward as if his legs had been knocked from beneath him. The man with the plasma torch slumped to the right, away from the struggling figure. Something many-legged scuttled across the camera, blotting everything from view for a blessed moment.

When the camera was clear again, the plasma torch was already alight.

“Oh, no,” Powell said.

The flare was blinding white. It surged across the cabin, and for a terrible few seconds the strapped-down miners’ bodies were sizzling and flaming, clothes burning and flesh flowing. Only one of them writhed in his bindings, and the thing protruding from his chest burst aside, becoming a mass of fire streaking across the cabin.

Then the plasma jet suddenly swept back and around, and everything went white.

Baxter hit his keyboard, going back to the cockpit view, and Gemma Keech was on fire.

He switched it off then. Even though everything they’d seen had been soundless, losing the image seemed to drop an awful silence across the bridge.

It was Hoop who moved first. He hit the AllShip intercom button and winced at the whine of crackling feedback.

“Lucy, we can’t let those ships dock,” he said into the microphone. “You hear me? The Delilah is... there are things on board. Monsters.” He closed his eyes, mourning his childhood’s lost innocence. “Everyone’s dead.”

“Oh, no!” Lachance said.

Hoop looked at him, and the Frenchman was staring down at the radar screen.

“Too late,” Lachance whispered. Hoop saw, and cursed himself. He should have thought of this! He struck the button again and started shouting.

“Jordan, Cornell, get out of there, get away from the docking level, far away as you can, run, run!” He only hoped they heard and took heed. But a moment later he realized it really didn’t matter.

The stricken Delilah ploughed into the Marion, and the impact and explosion knocked them all from their feet.

2

SAMSON

Everyone and everything was screaming.

Several warning sirens blasted their individual songs— proximity alert; damage indicator; hull breach. People shouted in panic, confusion, and fear. And behind it all was a deep, rumbling roar from the ship itself. The Marion was in pain, and its vast bulk was grinding itself apart.

Lucy and Cornell, Hoop thought from his position on the floor. But whether they were alive or dead didn’t change anything right now. He was senior officer on the bridge. As scared and shocked as all of them, but he had to take charge.

He grabbed a fixed seat and hauled himself upright. Lights flashed. Cords, paneling, and strip-lights swung where they had been knocked from their mountings. Artificial gravity still worked, at least. He closed his eyes and breathed deeply, trying to recall his training. There had been an in-depth module in their pre-flight sessions, called “Massive Damage Control,” and their guide—a grizzled old veteran of seven solar system moon habitations and three deep space exploration flights—had finished each talk with, But don’t forget YTF.

It took Hoop until the last talk to ask what he meant.

“Don’t forget...” the vet said, “you’re truly fucked.”

Everyone knew that a disaster like this meant the end. But that didn’t mean they wouldn’t fight until the last.

“Lachance!” Hoop said, but the pilot was already strapping himself into the flight seat that faced the largest window. His hands worked expertly across the controls, and if it weren’t for the insistent warning buzzers and sirens, Hoop might have been comforted.

“What about Captain Jordan and Cornell?” Powell asked.

“Not now,” Hoop said. “Is everyone all right?” He looked around the bridge. Baxter was strapping himself tight into his seat, dabbing at a bloodied nose. Welford and Powell held each other up against the curved wall at the bridge’s rear. Sneddon was on her hands and knees, blood dripping onto the floor beneath her.

She was shaking.

“Sneddon?” Hoop said.

“Yeah.” She looked up at him. There was a deep cut across her right cheek and nose. Her eyes were hazy and unfocussed.

Hoop went to her and helped her up, and Powell came with a first aid kit.

The Marion was juddering. A new siren had started blaring, and in the confusion Hoop couldn’t identify it.

“Lachance?”

“Atmosphere venting,” he said. “Hang on.” He scanned his instruments, tapping keyboards, tracing patterns on screens that would mean little to anyone else. Jordan could pilot the Marion if she absolutely had to. But Lachance was the most experienced astronaut among them.

“We’re screwed,” Powell said.

“Shut it,” Welford told him.

“That’s it,” Powell responded. “We’re screwed. Game over.”

“Just shut up!” Welford shouted.

“We should get to the escape pods!” Powell said.

Hoop tried not to listen to the exchange. He focussed on Lachance, strapped tightly into the pilot’s seat and doing his best to ignore the rhythmic shuddering emanating from somewhere deep in the ship. That doesn’t feel good, he thought.

The four docking bays were in a protruding level beneath the ship’s nose, more than five hundred yards from the engine room. Yet an impact like that could have caused catastrophic structural damage throughout the ship. The surest way to see the damage would be to view it firsthand, but the quickest assessment would come from their pilot and his instruments.

“Get out,” Powell continued, “get away before the Marion breaks up, down to the surface and—”

“And what?” Hoop snapped without turning around. “Survive on sand for the two years it’ll take a rescue mission to reach us? If the company even decides a rescue is feasible,” he added. “Now shut it!”

“Okay,” Lachance said. He rested his hands on the flight stick, and Hoop could almost feel him holding his breath. Hoop had always been amazed that such a huge vessel could be controlled via this one small control.

Lachance called it The Jesus Stick.

“Okay,” the pilot said again. “Looks like the Delilah took out the port arm of the docking level, Bays One and Two. Three might be damaged, can’t tell, sensors there are screwed. Four seems to be untouched. Atmosphere is venting from levels three, four, and five. All bulkhead doors have closed, but some secondary safety seals have malfunctioned and are still leaking.”

“So the rest of the Marion is airtight for now?” Hoop asked.

“For now, yes.” Lachance pointed at a schematic of the ship on one of his screens. “There’s still stuff going on at the crash site, though. I can’t see what, but I suspect there’s lots of debris moving around down there. Any part of that could do more damage to the ship. Rad levels seem constant, so I don’t think the Delilah’s fuel cell was compromised. But if its containment core is floating around down there...” He trailed off.

“So what’s the good news?” Sneddon asked.

“That was the good news,” Lachance said. “Marion’s lost two of her lateral dampers, three out of seven starboard sub-thrusters are out of action. And there’s this.” He pointed at another screen where lines danced and crossed.

“Orbital map?” Hoop asked.

“Right. We’ve been nudged out of orbit. And with those dampers and subs wasted, there’s no way to fix it.”

“How long?” Powell asked.

Lachance shrugged his muscular shoulders.

“Not quick. I’ll have to run some calculations.”

“But we’re all right for now?” Hoop asked. “The next minute, the next hour?”

“As far as I can see, yes.”

Hoop nodded and turned to the others. They were staring at him, and he was sure he returned their fear and shock. But he had to get a grip, and keep it. Move past this initial panic, shift into post-crash mode as quickly as he could.

“Kasyanov and Garcia?” he asked, looking at Baxter.

Baxter nodded and hit AllShip on the intercom.

“Kasyanov? Garcia?”

Nothing.

“Maybe the med bay vented,” Powell said. “It’s forward from here, not far above the docking bays.”

“Try on their personal comms,” Hoop said.

Baxter tapped keyboards and donned his headpiece again.

“Kasyanov, Garcia, you there?” He winced, then threw a switch that put what he heard on loudspeaker. There was a whine, interrupted by staccato ragged thudding.

“What the hell...?” they heard Kasyanov say, and everyone sighed with relief.

“You both okay?” Baxter asked.

“Fine. Trapped by... but okay. What happened?”

“Delilah hit us.” Baxter glanced up at Hoop.

“Tell them to stay where they are for now,” Hoop said. “Let’s stabilize things before we start moving around anymore.”

Baxter spoke again, and then just as Hoop thought of the second dropship, Sneddon asked, “What about the Samson?”

“Can you hail them?” Hoop asked.

Baxter tried several times, but was greeted only by static.

“Cameras,” Sneddon said.

“I’ve got no contact with them at all.”

“No, switch to the cameras in Bay Three,” Sneddon replied. “If they’re still coming in, and Jones sees the damage, he’ll aim for there.”

Baxter nodded, his hands drifting across the control panels.

A screen flickered into life. The picture jumped, but it showed a clear view out from the end of Bay Three’s docking arm.

“Shit” Hoop muttered.

The Samson was less than a minute away.

“But those things...” Sneddon said.

I wish you were still here, Lucy, Hoop thought. But Lucy and Cornell had to be dead. He was in charge. And now, with the Marion fatally damaged, an even more pressing danger was manifesting.

“We’ve got to get down there,” Hoop said. “Sneddon, Welford, with me. Let’s suit up.”

As Welford broke out the emergency space suits from units at the rear of the bridge, Hoop and Lachance exchanged glances. If anything happened to Hoop, Lachance was next in charge. But if it got to that stage, there’d be very little left for him to command.

“We’ll stay in contact all the time,” Hoop said.

“Great, that’ll help.” Lachance smiled and nodded.

As the three of them pulled on the atmosphere suits, the Marion shuddered one more time.

“Samson is docking,” Baxter said.

“Keep everything locked,” Hoop said. “Everything. Docking arm, airlock, inner vestibule.”

“Tight as a shark’s arse,” Lachance said.

We should be assessing damage, Hoop thought. Making sure the distress signal has transmitted, getting down to med bay, doing any emergency repairs that might give us more time.

But the Samson held dangers that were still very much a threat.

That was priority one.

* * *

Though he was now in command, Hoop couldn’t help viewing things through the eyes of chief engineer. Lights flickered on and off, indicating damaged ducting and cabling on several of the electrical loops. Suit sensors showed that atmosphere was relatively stable, though he had already told Sneddon and Welford that they were to keep their helmets locked on. Damage to the Marion might well be an ongoing process.

They eschewed the elevator to climb down two levels via the large central staircase. The ship still juddered, and now and then a deeper, heavier thud rattled in from somewhere far away. Hoop didn’t have a clue what it might be. The huge engines were isolated for now, never in use while they were in orbit. The life support generators were situated far toward the rear of the ship, close to the recreation rooms. All he could think was that the superstructure had been weakened so much in the crash that damage was spreading. Cracks forming. Airtight compartments being compromised and venting explosively to space.

If that was the case, they needn’t worry about their decaying orbit.

“Samson’s initiating the automatic docking sequence,” Baxter said through their suits’ comm link.

“Can you view on board?” Hoop asked.

“Negative. I’m still trying to get contact back online. Samson has gone quiet.”

“Keep us informed,” Hoop said. “We’ll be there soon.”

“What do we do when we get there?” Welford asked from behind him.

“Make sure everything’s locked up tight,” Sneddon said.

“Right,” Hoop agreed. “Sneddon, did you recognize those things we saw on the Delilah?” He said no more, and his companions’ breathing rattled in his headset.

“No,” Sneddon said. Her voice was low, quiet. “I’ve never seen or heard of anything like them.”

“It’s like they were hatching from inside the miners’ chests.”

“I’ve read everything I can about alien life-forms,” Sneddon said. “The first was discovered more than eighty years ago, and since then everything discovered through official missions has been reported, categorized wherever possible, captured, and analyzed. Nothing like this. Just... nothing. The closest analogy I can offer is a parasitic insect.”

“So if they hatched from the miners, what laid the eggs?” Welford asked. But Sneddon didn’t answer, and it was a question that didn’t bear thinking about right then.

“Whatever it was, we can’t let them on board,” Hoop said, more determined than ever. “They’re not that big— we lose one on the Marion, and we’ll never find it again.”

“Until it gets hungry,” Welford said.

“Is that what they were doing?” Hoop asked. “Eating?”

“Not sure,” Sneddon said.

They moved on silently, as if wrestling with thoughts about those strange, horrific alien creatures. Finally Hoop broke the silence.

“Well, Karen, if we get out of this, you’ll have something to report,” he said.

“I’ve already started making notes.” Sneddon’s voice sounded suddenly distant and strange, and Hoop thought there might be something wrong with his suit’s intercom.

“You’re just spooky,” Welford said, and the science officer chuckled.

“Come on,” Hoop said. “We’re getting close to the docking level. Keep your eyes open.” Another thud shook through the ship. If it really was an explosive decompression—one in a series—then keeping their eyes open would merely enable them to witness their doom as a bulkhead exploded, they were sucked out into space, and the force of the vented air shoved them away from the Marion.

He’d read about astronauts being blasted into space. Given a shove, they’d keep moving away from their ship, drifting until their air ran out and they suffocated. But worse were the cases of people who, for some reason—a badly connected tether, a stumble—drifted only slowly, so slowly, away from their craft, unable to return, dying while home was still within sight.

Sometimes a spacesuit’s air could last for up to two days.

They reached the end of the entry corridor leading down into the docking level. A bulkhead door had closed, and Hoop took a moment to check sensors. The atmosphere beyond seemed normal, so he input the override code and the locking mechanism whispered open.

A soft hiss, and the door slid into the wall.

The left branch led to Bays One and Two, the right to Three and Four. Ten yards along the left corridor, Hoop saw the blood.

“Oh, shit,” Welford said.

The wet splash on the wall spur beside the blast door was the size of a dinner plate. The blood had run, forming spidery lines toward the floor. It glistened, still wet.

“Let’s check,” Hoop said, but he was already quite certain what they would find. The door sensors had been damaged, but a quick look through the spy hole confirmed his suspicions. Beyond the door was vacuum. Wall paneling and systems ducting had been stripped away by the storm of air being sucked out. If the person who had left that blood spatter had been able to hang on until the blast doors automatically slammed shut...

But they were out there now, beyond the Marion, lost.

“One and Two definitely out of action,” Hoop said. “Blast doors seem to be holding well. Powell, don’t budge from that panel, and make sure all the doors behind us are locked up tight.”

“You’re sure?” Powell said in their headsets. “You’ll be trapped down there.”

“If compartments are still failing, it could fuck the whole ship,” Hoop said. “Yeah, I’m sure.”

He turned to the others. Sneddon was looking past him at the blood spatter, her eyes wide behind the suit glass.

“Hey,” Hoop said.

“Yeah.” She looked at him. Glanced away again. “I’m sorry, Hoop.”

“We’ve all lost friends. Let’s make sure we don’t lose any more.” They headed back along the opposite corridor, toward Bays Three and Four.

“Samson has docked,” Baxter said through the comm.

“On automatic?”

“Affirmative.” Most docking procedures were performed automatically, but Hoop knew that Vic Jones occasionally liked to fly manually. Not this time.

“Any contact?”

“Nothing. But I think I just saw a flicker on the screen. I’m working to get visual back, if nothing else.”

“Keep me posted. We need to know what’s going on inside that ship.” Hoop led the way. The blast door leading to Bays One and Two was still open, and they moved quickly through toward the undamaged docking areas.

Another vibration rumbled through the ship, transmitted up through the floor. Hoop pressed his gloved hand hard against the wall, leaning in, trying to feel the echoes of the mysterious impact. But they had already faded.

“Lachance, any idea what’s causing those impacts?”

“Negative. The ship seems steady.”

“Compartments failing, you think?”

“I don’t think so. If that was happening we’d be venting air to space, and that would act as thrust. I’d see movement in the Marion. As it is, her flight pattern seems to have stabilized into the slowly decaying orbit we talked about. We’re no longer geo-stationary, but we’re moving very slowly in comparison with the surface. Maybe ten miles per hour.”

“Okay. Something else, then. Something loose.”

“Take care down there,” Lachance said. He wasn’t usually one to offer platitudes.

They passed through two more bulkhead doors, checking the sensors both times to ensure that the compartments on the other side were still pressurized. As they neared bays Three and Four, Hoop knew they’d have a visual on the damage.

The docking bays were contained in two projections from the underside of the Marion. One and Two were contained in the port projection, Three and Four in the starboard. As they neared the corridor leading into bays Three and Four, there were viewing windows on both sides.

“Oh, hell,” Hoop muttered. He was the first to see, and he heard shocked gasps from Sneddon and Welford.

The front third of the port projection, including the docking arms and parts of the airlock structures, had been swept away as if by a giant hand. Bay One was completely gone, torn aside to leave a ragged wound behind. Parts of Bay Two were still intact, including one long shred of the docking arm which was the source of the intermittent impacts—snagged on the end of the loose reach of torn metal and sparking cables was a chunk of the Delilah. The size of several people, weighing maybe ten tons, the unidentifiable mass of metal, paneling, and electrics bounced from the underside of the Marion, swept down, ricocheted from the ruined superstructure of Bay Two, then bounced back up again.

Each strike gave it the momentum to return. It moved slowly, but such was its weight that the impact when it came was still enough to send vibrations through the entire belly of the ship.

The Delilah had all but disintegrated when it hit. Detritus from the crash still drifted with the Marion, and in the distance, silhouetted against the planet’s stormy surface, Hoop could see larger chunks slowly moving away from them.

“That’s a person out there,” Welford said quietly, pointing. Hoop saw the shape pressed against the remains of Bay Two, impaled on some of the torn metal superstructure. He couldn’t tell the sex. The body was badly mutilated, naked, and most of its head was missing.

“I hope they all died quickly,” Sneddon said.

“They were already dead!” Hoop snapped. He sighed, and raised a hand in apology. His heart was racing. Seventeen years in space and he’d never seen anything like this. People died all the time, of course, because space was such an inimical environment. Accidents were common, and it was the larger disasters that gained notoriety. The passenger ship Archimedes, struck by a hail of micro meteors on its way to Alpha Centurai, with the loss of seven hundred passengers and crew. The Colonial Marine base on a large moon in the Outer Rim, its environmental systems sabotaged, resulting in the loss of over a thousand personnel.

Even further back, in the fledgling days of space travel, the research station Nephilim orbiting Ganymede suffered stabilizer malfunction and spun down onto the moon’s surface. That one was still taught to anyone planning a career in space exploration, because every one of the three hundred people on board had continued with their experiments, transmitting data and messages of hope until the very last moment. It had been a symbol of humankind’s determination to edge out past the confines of their own planet, and eventually their own system.

In the scheme of things, this tragedy was small. But Hoop had known every one of those people on board the Delilah. And even though he couldn’t identify the frozen, ruined body stuck against the wrecked docking bay structure, he knew that he had spoken, joked, and laughed with them.

“We’ll have to cut that free,” Welford said, and at first Hoop thought he was talking about the corpse. But the engineer was watching the slowly drifting mass of metal as it moved back toward the shattered docking bays.

“We’ve got to do that and a lot more,” Hoop said. If they were to survive—if they got past this initial chaos, secured the Samson, figured out what the fuck was going on—he, Welford, and Powell needed to pull some miracles out of somewhere. “Gonna earn our pay now, guys.”

“Hoop, the Samson,” Baxter muttered in his ear.

“What is it?” They couldn’t yet see the ship where it was now static on the other side of the starboard docking arm.

“I’ve got it... a picture, up on screen.” His voice sounded hollow, empty.

“And?” Sneddon asked.

“And you don’t want to open it up. Ever. Don’t even go near it.”

Hoop wished he could see, though part of him was glad that he couldn’t.

“What’s happening in there?” Sneddon asked.

“They’ve... they’ve hatched,” Baxter said. “And they’re just... waiting. Those things, just sort of crouched there beside the bodies.”

“What about Jones and Sticky?”

“Sticky’s dead. Jones isn’t.” That flat tone again, so that Hoop didn’t really want to ask any more. But Sneddon did. Maybe it was her science officer’s curiosity.

“What’s happening to Jones?” she asked.

“Nothing. He’s... I can see him, just at the bottom of the picture. He’s just sitting there, seat turned around, back against the control panel. Shaking and crying.”

They haven’t killed him yet, Hoop thought.

“We have to seal this up,” he said. “All the doors are locked down anyway, but we have to disable all of the manual controls.”

“You think those things can open doors?” Welford asked.

“Hoop’s right,” Sneddon said. “We must assume the worst.”

“Can’t we just cut the Samson loose?”

Hoop had already thought of that. But despite the danger, they might still need the dropship. The Marion’s orbit was still decaying. There were escape pods, but their targeting was uncertain. If they used them, they’d end up scattered across the surface of the planet.

The Samson might be their only hope of survival.

“We do that and it might drift with us for days,” Lachance said, his voice coming through a hail of static. “Impact the Marion, cause more damage. We’re in bad enough shape as it is.”

“Baxter, we’re losing you,” Hoop said.

“...damaged,” Baxter said. “Lachance?”

“He’s right,” Lachance responded. “Indicators are flagging up more damage every minute that goes by. Comms, environmental, remote system. We need to start fixing things.”

“Got to fix this first,” Hoop said. “We go through the vestibule, into the docking arm for Bay Three, then into the airlock. Then from there we work back out, disabling manual controls and shutting everything down.”

“We could purge the airlock, too,” Welford said.

“Good idea. If anything does escape from the Samson, it won’t be able to breathe.”

“Who’s to say that they breathe at all?” Sneddon said. “We don’t know what they are, where they come from. Mammal, insectile, reptilian, something else. Don’t know anything!” Her voice was tinged with panic.

“And it’s going to stay that way,” Hoop said. “First chance we get, we kill them. All of them.”

He wanted support from someone, but no one replied. He expected disagreement from Sneddon—as science officer, she’d see past the chaos and death to what these creatures might mean for science. But she said nothing, just stared at him, her eyes bruised, cut nose swelling.

I really am in charge now, he thought. It weighed heavy.

“Right,” he said. “Let’s get to it.”

* * *

They followed Hoop’s plan.

In through the vestibule that served bays Three and Four, through the docking arm, then through the airlock to the outer hatch. Hoop and Welford went ahead, leaving Sneddon to close the doors behind them, and at the end of the docking arm the two men paused. Beyond the closed hatch lay a narrow gap, and then the Samson’s outer airlock door. There was a small viewing window in both hatch and door.

The inside of the Samson’s window was steamed up.

Hoop wondered whether the things knew they were there, so close. He thought of asking Baxter, but silence seemed wisest. Silence, and speed.

They quickly dismantled the hatch’s locking mechanism and disabled it, disconnecting the power source. It would need to be repaired before the hatch could be opened again. Much stronger than the bathroom door on the Delilah. The thought didn’t comfort Hoop as much as it should have.

They worked backward, and when they’d disabled the door mechanism between docking arm and vestibule, Welford purged the atmosphere. The doors creaked slightly under the altered pressures.

Outside the vestibule, Sneddon waited.

“Done?” she asked.

“Just this last door,” Hoop said. Welford went to work.