Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: e-artnow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

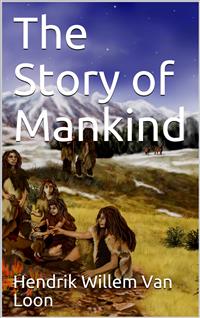

Ancient Man – The Beginning of Civilizations is a children's history book that offers a thorough understanding of the growth and the experience of the human race. The author explains the emergence of man from the darkness of prehistory through all the phases of civilization and human evolution, taking the reader's hand and leading him to explore the obscure wilderness of the bygone ages.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 134

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ancient Man – The Beginning of Civilizations (Illustrated Edition)

Table of Contents

My darling boys,

You are twelve and eight years old. Soon you will be grown up. You will leave home and begin your own lives. I have been thinking about that day, wondering what I could do to help you. At last, I have had an idea. The best compass is a thorough understanding of the growth and the experience of the human race. Why should I not write a special history for you?

So I took my faithful Corona and five bottles of ink and a box of matches and a bale of paper and began to work upon the first volume. If all goes well there will be eight more and they will tell you what you ought to know of the last six thousand years.

But before you start to read let me explain what I intend to do.

I am not going to present you with a textbook. Neither will it be a volume of pictures. It will not even be a regular history in the accepted sense of the word.

I shall just take both of you by the hand and together we shall wander forth to explore the intricate wilderness of the bygone ages.

I shall show you mysterious rivers which seem to come from nowhere and which are doomed to reach no ultimate destination.

I shall bring you close to dangerous abysses, hidden carefully beneath a thick overgrowth of pleasant but deceiving romance.

Here and there we shall leave the beaten track to scale a solitary and lonely peak, towering high above the surrounding country.

Unless we are very lucky we shall sometimes lose ourselves in a sudden and dense fog of ignorance.

Wherever we go we must carry our warm cloak of human sympathy and understanding for vast tracts of land will prove to be a sterile desert--swept by icy storms of popular prejudice and personal greed and unless we come well prepared we shall forsake our faith in humanity and that, dear boys, would be the worst thing that could happen to any of us.

I shall not pretend to be an infallible guide. Whenever you have a chance, take counsel with other travelers who have passed along the same route before. Compare their observations with mine and if this leads you to different conclusions, I shall certainly not be angry with you.

I have never preached to you in times gone by.

I am not going to preach to you today.

You know what the world expects of you--that you shall do your share of the common task and shall do it bravely and cheerfully.

If these books can help you, so much the better.

And with all my love I dedicate these histories to you and to the boys and girls who shall keep you company on the voyage through life.

HENDRIK WILLEM VAN LOON.

Prehistoric Man

It took Columbus more than four weeks to sail from Spain to the West Indian Islands. We on the other hand cross the ocean in sixteen hours in a flying machine.

Five hundred years ago, three or four years were necessary to copy a book by hand. We possess linotype machines and rotary presses and we can print a new book in a couple of days.

We understand a great deal about anatomy and chemistry and mineralogy and we are familiar with a thousand different branches of science of which the very name was unknown to the people of the past.

In one respect, however, we are quite as ignorant as the most primitive of men--we do not know where we came from. We do not know how or why or when the human race began its career upon this Earth. With a million facts at our disposal we are still obliged to follow the example of the fairy-stories and begin in the old way:

"Once upon a time there was a man."

This man lived hundreds of thousands of years ago.

What did he look like?

We do not know. We never saw his picture. Deep in the clay of an ancient soil we have sometimes found a few pieces of his skeleton. They were hidden amidst masses of bones of animals that have long since disappeared from the face of the earth. We have taken these bones and they allow us to reconstruct the strange creature who happens to be our ancestor.

The great-great-grandfather of the human race was a very ugly and unattractive mammal. He was quite small. The heat of the sun and the biting wind of the cold winter had colored his skin a dark brown. His head and most of his body were covered with long hair. He had very thin but strong fingers which made his hands look like those of a monkey. His forehead was low and his jaw was like the jaw of a wild animal which uses its teeth both as fork and knife.

He wore no clothes. He had seen no fire except the flames of the rumbling volcanoes which filled the earth with their smoke and their lava.

He lived in the damp blackness of vast forests.

When he felt the pangs of hunger he ate raw leaves and the roots of plants or he stole the eggs from the nest of an angry bird.

Once in a while, after a long and patient chase, he managed to catch a sparrow or a small wild dog or perhaps a rabbit These he would eat raw, for prehistoric man did not know that food could be cooked.

His teeth were large and looked like the teeth of many of our own animals.

During the hours of day this primitive human being went about in search of food for himself and his wife and his young.

At night, frightened by the noise of the beasts, who were in search of prey, he would creep into a hollow tree or he would hide himself behind a few big boulders, covered with moss and great, big spiders.

In summer he was exposed to the scorching rays of the sun.

During the winter he froze with cold.

When he hurt himself (and hunting animals are for ever breaking their bones or spraining their ankles) he had no one to take care of him.

He had learned how to make certain sounds to warn his fellow-beings whenever danger threatened. In this he resembled a dog who barks when a stranger approaches. In many other respects he was far less attractive than a well-bred house pet.

Altogether, early man was a miserable creature who lived in a world of fright and hunger, who was surrounded by a thousand enemies and who was for ever haunted by the vision of friends and relatives who had been eaten up by wolves and bears and the terrible sabre-toothed tiger.

Of the earliest history of this man we know nothing. He had no tools and he built no homes. He lived and died and left no traces of his existence. We keep track of him through his bones and they tell us that he lived more than two thousand centuries ago.

The rest is darkness.

Until we reach the time of the famous Stone Age, when man learned the first rudimentary principles of what we call civilization.

Of this Stone Age I must tell you in some detail.

The World Grows Cold

Something was the matter with the weather.

Early man did not know what "time" meant.

He kept no records of birthdays and wedding-anniversaries or the hour of death.

He had no idea of days or weeks or years.

When the sun arose in the morning he did not say "Behold another day." He said "It is Light" and he used the rays of the early sun to gather food for his family.

When it grew dark, he returned to his wife and children, gave them part of the day's catch (some berries and a few birds), stuffed himself full with raw meat and went to sleep.

In a very general way he kept track of the seasons. Long experience had taught him that the cold Winter was invariably followed by the mild Spring--that Spring grew into the hot Summer when fruits ripened and the wild ears of corn were ready to be plucked and eaten. The Summer ended when gusts of wind swept the leaves from the trees and when a number of animals crept into their holes to make ready for the long hibernal sleep.

It had always been that way. Early man accepted these useful changes of cold and warm but asked no questions. He lived and that was enough to satisfy him.

Suddenly, however, something happened that worried him greatly.

The warm days of Summer had come very late. The fruits had not ripened at all. The tops of the mountains which used to be covered with grass lay deeply hidden under a heavy burden of snow.

Then one morning quite a number of wild people, different from the other inhabitants of his valley had approached from the region of the high peaks.

They muttered sounds which no one could understand. They looked lean and appeared to be starving. Hunger and cold seemed to have driven them from their former homes.

There was not enough food in the valley for both the old inhabitants and the newcomers. When they tried to stay more than a few days there was a terrible fight and whole families were killed. The others fled into the woods and were not seen again.

For a long time nothing occurred of any importance.

But all the while, the days grew shorter and the nights were colder than they ought to have been.

Finally, in a gap between the two high hills, there appeared a tiny speck of greenish ice. It increased in size as the years went by. Very slowly a gigantic glacier was sliding down the slopes of the mountain ridge. Huge stones were being pushed into the valley. With the noise of a dozen thunderstorms they suddenly tumbled among the frightened people and killed them while they slept. Century-old trees were crushed into kindling wood by the high walls of ice that knew of no mercy to either man or beast.

At last, it began to snow.

It snowed for months and months and months.

All the plants died. The animals fled in search of the southern sun. The valley became uninhabitable. Man hoisted his children upon his back, took the few pieces of stone which he had used as a weapon and went forth to find a new home.

Why the world should have grown cold at that particular moment, we do not know. We can not even guess at the cause.

The gradual lowering of the temperature, however, made a great difference to the human race.

For a time it looked as if every one would die. But in the end this period of suffering proved a real blessing. It killed all the weaker people and forced the survivors to sharpen their wits lest they perish, too.

Placed before the choice of hard thinking or quick dying the same brain that had first turned a stone into a hatchet now solved difficulties which had never faced the older generations.

In the first place, there was the question of clothing. It had grown much too cold to do without some sort of artificial covering. Bears and bisons and other animals who live in northern regions are protected against snow and ice by a heavy coat of fur. Man possessed no such coat. His skin was very delicate and he suffered greatly.

He solved his problem in a very simple fashion. He dug a hole and he covered it with branches and leaves and a little grass. A bear came by and fell into this artificial cave. Man waited until the creature was weak from lack of food and then killed him with many blows of a big stone. With a sharp piece of flint he cut the fur of the animal's back. Then he dried it in the sparse rays of the sun, put it around his own shoulders and enjoyed the same warmth that had formerly kept the bear happy and comfortable.

Then there was the housing problem. Many animals were in the habit of sleeping in a dark cave. Man followed their example and searched until he found an empty grotto. He shared it with bats and all sorts of creeping insects but this he did not mind. His new home kept him warm and that was enough.

Often, during a thunderstorm a tree had been hit by lightning. Sometimes the entire forest had been set on fire. Man had seen these forest-fires. When he had come too near he had been driven away by the heat. He now remembered that fire gave warmth.

Thus far, fire had been an enemy.

Now it became a friend.

A dead tree, dragged into a cave and lighted by means of smouldering branches from a burning forest filled the room with unusual but very pleasant heat.

Perhaps you will laugh. All these things seem so very simple. They are very simple to us because some one, ages and ages ago, was clever enough to think of them. But the first cave that was made comfortable by the fire of an old log attracted more attention than the first house that ever was lighted by electricity.

When at last, a specially brilliant fellow hit upon the idea of throwing raw meat into the hot ashes before eating it, he added something to the sum total of human knowledge which made the cave-man feel that the height of civilization had been reached.

Nowadays, when we hear of another marvelous invention we are very proud.

"What more," we ask, "can the human brain accomplish?"

And we smile contentedly for we live in the most remarkable of all ages and no one has ever performed such miracles as our engineers and our chemists.

Forty thousand years ago when the world was on the point of freezing to death, an unkempt and unwashed cave-man, pulling the feathers out of a half-dead chicken with the help of his brown fingers and his big white teeth--throwing the feathers and the bones upon the same floor that served him and his family as a bed, felt just as happy and just as proud when he was taught how the hot cinders of a fire would change raw meat into a delicious meal.

"What a wonderful age," he would exclaim and he would lie down amidst the decaying skeletons of the animals which had served him as his dinner and he would dream of his own perfection while bats, as large as small dogs, flew restlessly through the cave and while rats, as big as small cats, rummaged among the left overs.

Quite often the cave gave way to the pressure of the surrounding rock. Then man was hurled amidst the bones of his own victims.

Thousands of years later the anthropologist (ask your father what that means) comes along with his little spade and his wheelbarrow.

He digs and he digs and at last he uncovers this age-old tragedy and makes it possible for me to tell you all about it.

The End of the Stone Age

The struggle to keep alive during the cold period was terrible. Many races of men and animals, whose bones we have found, disappeared from the face of the earth.