0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

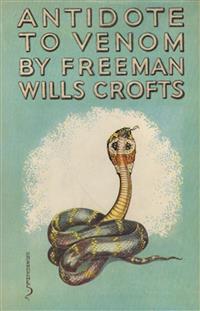

In an English city zoo a murderer plans to use snake venom to kill an old professor, hoping to inherit a fortune. In this unusual detective story we are shown the planning of the crime. When Inspector French is called in to solve the mystery we learn how an ingenious murder has been committed and follow the actions of the guilty men.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Antidote to Venom

First published in 1938

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Antidote to Venom

Author’s Note

This book is a two-fold experiment: first, it is an attempt to combine the direct and inverted types of detective story and second, an effort to tell a story of crime positively.

I should like to express my gratitude to Mr. E. G. Boulenger (Director of the Aquarium and Curator of Reptiles in the Zoological Society’s Gardens, London) for his kindness in reading my script and advising on matters connected with the Zoo.

F. W. C.

Contents

Chapter

Page

I.

Venom: In the Family

5

II.

Venom: In the Office

17

III.

Venom: Through the Eye

30

IV.

Venom: Through the Affections

40

V.

Venom: Through the Pocket

53

VI.

Venom: In Society

63

VII.

Venom: Through Surroundings

75

VIII.

Venom: Through Temptation

91

IX.

Venom: In Action

105

X.

Venom: Through Falsehood

115

XI.

Venom: Through Murder

129

XII.

Venom: Through Deceit

143

XIII.

Venom: Through the Law

154

XIV.

Venom: In the Mind

168

XV.

Venom: In the Press

180

XVI.

Venom: In the Conference

194

XVII.

Venom: Through Interrogation

208

XVIII.

Venom: In the Workshop

220

XIX.

Venom: From the River

230

XX.

Venom: The Reckoning

243

XXI.

Venom: Through Death

253

XXII.

Venom: Through the Tongue

263

XXIII.

Venom: The Antidote

274

Chapter IVenom: In the Family

George Surridge entered his study shortly before seven on a cold night in mid October. He was in an irritable frame of mind, the result of an unusual crescendo of small worries. It had been one of those days on which everything had gone wrong, the last straw being provided by an aching tooth which had gnawed itself into his consciousness through all that he did. He had meant to go down town and have it seen to, but one thing after another had cropped up to prevent him. With more than usual pleasure he had been looking forward to this half-hour of relaxation before dinner.

But even now the tendency persisted. As he glanced at the fire his brow darkened. It had been allowed to go down and the room was cold. How many times, he asked himself savagely, did that confounded girl need to be told to have it burning up brightly when he came in? Why couldn’t she do what she was asked? His hand strayed towards the bell, then desisted. What was the good? If he said enough to make any impression on her she would leave and then there would be hell to pay with Clarissa. He glanced at the wood bucket. For a wonder there was something in it. Irritably he raked the coals together and threw on a couple of blocks. Then crossing the room he poured himself out a stiff whisky and soda.

He carried the glass to his arm-chair, and picking up the evening paper which he had brought in with him but laid aside, he sat down with a grunt of relief.

He turned to the financial pages. Stocks were dropping, and considering the state of the country, he didn’t see why they should. There was talk of another slump and the idea frightened him. For money meant a good deal to George Surridge. As it was he was hard up, and if things grew worse his position might become really serious.

He was a man of rather undistinguished appearance, of the type which would inevitably pass unnoticed in a crowd. Of medium height and build, he was neither markedly well or ill favoured in face. His hair, of a medium shade of brown, was greying at the temples. His forehead was perhaps his best feature, fairly high though not broad, but his mouth was weak and his eyes a trifle shifty. He looked tired and worried and old for his age, which was forty-six.

But though he seemed to be bearing his share of trouble, a casual acquaintance would have said he had little reason to grumble. He held a good job. George Surridge was Director of the Birmington Corporation Zoo; and the Birmington Zoo was claimed by Birmington people as the second zoo in the country: smaller perhaps than London—though not a whit inferior—but larger and better than any other. This post gave him a good social position in the city, an adequate salary and free occupation of the comfortable house in which he was now seated, not to speak of coal and these logs—which had now burst into a blaze and begun to give out heat—as well as the electric current which was lighting his reading lamp.

It was certainly a snug enough post, and unless he made some serious break, secure. The work also was congenial. He loved animals and they seemed to recognise in him a friend. So far none of them had ever turned on him or shown temper when he was with them. On the whole, too, he got on reasonably well with his staff. If his relations with his wife had been equally satisfactory he might have been more content, but unhappily these left a good deal to be desired.

He settled down comfortably with his whisky and newspaper. This little rest should help him, and by dinner time he should be feeling normal.

He was not, however, to be allowed to enjoy his relaxation. He had read for a few moments only when the door opened and his wife entered. She was dressed for the street and had evidently just reached home.

Clarissa Surridge was a woman striking enough looking to attract the eye of the casual passer-by. Tall, and with a presence, her well cut clothes accentuated the lines of her fine figure. Her pale oval face had good features, though a discontented and rather unhappy expression. In spite of her make-up—usually much too lavish for her husband’s taste—little lines appeared on her forehead and at the corners of her eyes, while streaks of grey marked her dark hair. Now she looked upset and annoyed and George saw that he was in for trouble.

“Oh, you’re home?” she began ungraciously, then continued in a hard unsympathetic voice. “The car’s broken down again. I thought I’d never get back. Either the car’s done or Pratt doesn’t know how to manage it.”

George’s heart sank. The car undoubtedly was old. It had been a good Mortin in its day, but of course five years was five years. It was certainly shabby, though the engine was sound. Recently he had had a re-bore and he had also got a new battery, tyres and other fittings. It really wasn’t too bad.

“What’s the matter now?” he asked, with an unpleasant accent on the last word.

Clarissa closed the door, not too gently, and advanced into the room. “I’ve just told you. What are you going to do about it?”

“Nothing. The car’s all right.” He glanced down at his paper as if he had closed the subject, then looked up again. “What went wrong?”

“How do I know? I’m not a mechanic.” Her voice indicated with uncompromising clarity that the subject was anything but closed.

“Well, what happened?” went on George impatiently.

“It stopped.” His wife warmed to her subject as she proceeded to develop it. “I had just set down Margaret Marr at a shop when it stopped: there in King Street in the middle of the traffic. The police came over and a crowd gathered while it was being pushed into the kerb. I don’t know when I felt such a fool.”

“What has Pratt done about it?”

“I don’t know what he’s done about it and I care less. What I know is that it’s the third time it has happened in a couple of months.”

George Surridge jerked himself about in his chair. Really women’s notions were the limit. “Rubbish,” he said shortly. “Every car goes wrong occasionally.”

“Well, as I tell you, it’s gone wrong once too often. I give you warning I’m not going on with it any longer. Why, it’s six years old if it’s a day.”

“Five.”

“It’s the same thing. When are you going to get a new one? I’ve spoken about it often enough.”

“Speaking about it won’t provide the money. I’ve told you I can’t afford it at present.”

“What nonsense! You have plenty of money. If not, where has it all gone to?”

George lifted his paper again as if to read, then once again dropped it. “You would have all that painting done. Only for that I might have managed it.”

If this was meant as an olive branch, it failed in its purpose. Clarissa’s eyes flashed angrily and her voice took on a more bitter tone. “Oh, my fault, of course. That painting! Why, it’s years since anything was done. And your committee friends wouldn’t move, though it was their liability. I suppose they have no money either.”

“They thought they had done enough for one year with the new electric wiring.”

“Yes, tear the place to bits and then leave it like that! I’d like to know how I was to have my friends in if the house was like a pigsty?”

This touched a sore spot and George reacted accordingly. “I could do without them all right,” he declared grimly, and as the thought of his grievances grew, he went on with a rising inflexion. “Here I come home after sweating all day for you and your house and I want a little peace, and there’s never a minute I can call my own.”

“And what about me?” Clarissa retorted. “Do you think I do nothing all day? Haven’t I got this house to run—on half nothing? And you grudge me a little relaxation.”

George Surridge all but laughed as he compared this picture of his wife’s existence with the reality. Actually she lived her own life among her own friends, keeping her own council, and using the house as a sort of inferior hotel, of which, owing to its unfashionable situation, she was slightly ashamed. “A little relaxation?” he retorted. “Hang it all, don’t be an utter fool. Look here,” he felt he had spoken improperly and was sorry, but could not bring himself to apologise, “forget what I said. Let’s have a quiet evening for once in away and I’ll see what I can do about the car.”

Clarissa smiled maliciously. “If you had wanted a quiet evening you shouldn’t have invited your aunt to dinner.”

“Oh hell! I forgot about her.”

“Not my friends this time.”

George waved his paper irritably. “We have to do it, as you know very well. If she thought she didn’t get proper attention, she’s quite capable of altering her will.”

“She’ll perhaps see through your affection and do it in any case.” Swinging on her heel, Clarissa left the room, while George sat on before the now dying fire, gazing gloomily into the cooling embers.

The scene with his wife had not unduly upset him. Unhappily he had grown accustomed to such an atmosphere, as for many years it had been the normal one existing between them. There were indeed few subjects they could discuss without heat, and not infrequently recriminations were much more bitter than on this evening.

His thoughts travelled back over the path his steps had so far followed. He had been lucky as a youth. He had had good parents, a comfortable home, an excellent education and enough money to enable him to choose his career. He had always loved animals, but at first the idea of becoming connected with a zoo had not occurred to him. He had taken his degree in veterinary surgery, intending to set up in one of the hunting counties. Then a small mischance had given a new twist to his ideas.

Driving to the wharves in Antwerp on his return from a holiday in Germany, a slight collision with another car had caused him to miss his boat. With some hours to spare before the next, he had naturally gravitated to the Zoo. In passing through the gardens he had observed on an office door the inscription, “Bureau du Directeur.” The idea that here was his life’s work leapt into his mind and his first care on returning to England was to make an appointment with the Director of the London Zoo to ask about possibilities.

Luckily or unluckily for him, it happened that at that very moment the Director was in need of a junior assistant. He took to his visitor personally, and was pleased not only with his obvious love for animals, but the fact that he was a qualified veterinary surgeon. To make a long story short, he offered him a job, which was instantly and rapturously accepted.

Young George Surridge’s heart was in his work and he gave satisfaction. In six years he was promoted twice, and at the end of ten he found himself second in command and his chief’s right hand man.

Then he fell in love.

It happened that some months before his last promotion George was sent on business to the house of a Mr. Ellington, a City magnate who lived in St. John’s Wood. This gentleman had a tiny aquarium stocked with rare fish small in dimension but spectacular as to shape and colour. He was anxious to extend his collection and had consulted George’s chief on the project. George’s job was to view the site and assist with expert advice.

Ellington found the young man interesting and kept him to tea. There George met Mrs. Ellington and her two daughters. Clarissa, the elder, he admired immensely, though no thought of love at that time entered his mind.

The progress of the new aquarium involved further visits and George gradually grew more and more intimate with the family. He soon learned that both daughters were engaged, Clarissa to an artist and Joan to an officer in the Guards. The artist he detested at sight, privately diagnosing him, with a callous disregard to the purity of metaphor, as a weedy gasbag.

As time passed, in spite of his quite genuine efforts to prevent it, he found his admiration of Clarissa growing into a very real love. He was honourably minded and he felt he should avoid the house, but the job still required his presence, and when Clarissa asked him to wait for lunch or tea, as she often did, he had not the strength to refuse.

So matters dragged on for some time and then, just after George’s promotion to the position of Chief Assistant, there came a fresh development. Clarissa and the artist had a terrible quarrel. George never knew what it was about, but it ended in Clarissa breaking off the engagement.

George at first was stunned by the possibilities now opening out before him. Just as he had obtained his new job and reached a position in which he could afford to marry, the girl he had so hopelessly loved had become free. He scarcely dared to think that she would accept him, owing to the difference of their social stations. However, after waiting for a reasonable time he took his courage in both hands and proposed. To his surprise she accepted him, and a few months later they were married.

Then for George there set in a period of disillusionment, which grew more and more heartbreaking as the weeks passed. Clarissa before marriage had cheerfully accepted all the disabilities which he had warned her would result from what, in comparison with her previous life, would be straightened circumstances. Her acceptance had, he was sure, been perfectly honest, but she had not realised to what she was agreeing. When, for example, she found they were travelling second class on their honeymoon to Switzerland, she had frowned, though without remark. And when at Pontresina they had gone to a comparatively primitive hotel with small rooms and without private baths, she had been a little short. It was not, he felt sure, inconsistency on her part. It was simply that she had never before in her life travelled otherwise than in the lap of luxury.

This question of money was not referred to between them, but it loomed larger and larger in his thoughts and it spoiled his pleasure. Rightly or wrongly, he felt Clarissa was looking down on the entertainment which he was able to provide, and he grew correspondingly awkward and distant in manner, a change to which she reacted unhappily. At the same time there began to grow up in his heart a sense of grievance against her. She had money of her own, but she never offered to share the financial burden. At first he clung to the view that this was to spare his pride, and he certainly would have felt affronted if she had offered to pay for the holiday. But he did think she might occasionally have said: “Look here, let’s go halves in this,” or sometimes have paid for the occasional special excursions they took, some of which were quite expensive.

Though he sincerely tried to make excuses for her, this money question spoiled their honeymoon, and both were glad when they set their faces homewards. Often afterwards he thought that if he had been honest with her and told her directly of his difficulties, a happy understanding might have been reached. But his pride stepped in and prevented him.

When they reached London and set up in what was to her a tiny and rather inconvenient house, this bar to their happiness remained. It was true that Clarissa did now spend money on their establishment, but he gradually found that it was only on things which benefited herself, not on those they used jointly. They settled down, however, as well as do a great many other married couples. Outwardly they were amicable enough and they avoided the bitter quarrels that separated some of their friends. But they had little real fellowship. George’s love for his wife gradually died, and he began to ask himself whether she had ever felt any at all for him.

When they had been married some eight years, George obtained one of the plums of the zoological world: the directorship of the Birmington Zoo. A new house among new surroundings and the breaking of certain old ties might bring about that reconciliation and companionship for which he so much longed. From every point of view he was delighted at the prospect and he moved to the Midlands with enthusiasm.

Once again he was disappointed. Though from a professional point of view the change left nothing to be desired, the effect on his home life was bad rather than good. In the new city Clarissa missed her friends. Moreover she did not particularly take to the Midlanders. With her metropolitan standards she was inclined to look down upon them as provincials. They quickly sensed her feeling and their welcome grew less friendly. Clarissa became lonely and unhappy.

This is not to say that she did not make friends. Both she and George made a number, but the process proved slower than it need have done.

In Birmington, as in Switzerland and London, the question of money tended to prevent real good fellowship developing between husband and wife. As director, George was now in receipt of a much larger salary than formerly, as well as a free house, rates, and other perquisites. If Clarissa had been content with their former scale of living, it would have greatly eased his position, enabling him to insure and to save against a rainy day, as he wished. But with the larger salary her demands grew greater, and while they lived in a better way, it took almost the whole of the larger salary to do it.

In that ten years of life at Birmington, relations between the couple had slowly deteriorated. At times George felt he absolutely hated his wife. They still had had no direct breach, but he could not be blind to the fact that one might occur at any moment.

He felt old and dispirited, did George Surridge, as he sat on in his study gazing morosely into the dying fire. A sense of futility oppressed him, a sense that nothing he was doing was worth while and that much he was occupied with would be better left undone. Besides the unhappiness of his home, another matter, even more serious, was preying on his mind. He had been idiotic enough, for sheer amusement and relaxation, to get into a gambling set at the club. He had lost, and was losing, more than he could afford, and yet he didn’t want to stop playing. The men he met were a pleasant crowd, indeed they seemed to him at times the best friends he had. He saw, however, that he must break with them, for the simple reason that he couldn’t afford the continued drain on his pocket. This he had realised for some months, yet when they invited him to join them he had not had the strength to refuse, telling himself on each occasion that this time he must win, and that if he did, never again would he touch a card.

His thoughts swung round into a familiar channel. If only his old aunt would die and leave him her money! She was well-to-do, was Miss Lucy Pentland, not exactly wealthy, but obviously with a comfortable little fortune enough, and she had on more than one occasion told him that he would be her heir. Moreover, she was in poor health. In the nature of things she could not last very much longer. If only she would die!

Surridge pulled himself up, slightly ashamed of himself. He did not of course wish the old lady any harm. Quite the reverse. But really, when people reached a certain age their usefulness was over. And in his opinion she had reached and passed that stage. She could not enjoy her life. If she were to die, what a difference it would make to him!

Thoughts of her reminded him that she was probably at that moment on her way to the house. The evening would be trying. She was a little deaf and was hard to entertain. Thank goodness she liked to go home early.

Finishing his whisky, Surridge went upstairs to change for dinner.

Chapter IIVenom: In the Office

Shortly after nine next morning George Surridge left his house, which stood, screened off from the public by a belt of Scotch firs, in a corner of the Zoological Gardens, and walked along the private path to his office in the adjoining lot. This also was separated from the public by vegetation, though here in the form of a privet hedge. The office stood on raised ground, and from the chair at his desk George could see over the hedge and the flower borders down the main walk of the Gardens, which ran wide and straight right across the area to the entrance gate. From a casual inspection of the crowds on this walk, together with a glance at the hands of the clock on his chimneypiece, long practice had enabled him to form a close approximation of the turnstile records, and therefore of the important matter of the day’s takings.

With his customary “Morning, Harley,” to the clerk in the outer office, and “Morning, Miss Hepworth,” to his secretary in her little ante-room, George entered his private room. It was well furnished and comfortable. A roaring fire blazed up the chimney, and the tidyness of the books and papers and the spotless cleanliness of the windows and furniture showed that George could command attentive service. On the blotting pad on the large flat desk stood a pile of opened letters, with to the left a newspaper and a couple of periodicals. After a moment before the fire George sat down at the desk and pressed a button. Miss Hepworth entered with her pencil and pad and in silence took her place at a small table close by.

She was a rather baffling sort of girl. Always neatly dressed and competent looking, though not exactly a beauty, she was reserved to the verge of actual hostility. To George she was a complete enigma. He never could tell what she was thinking about, if indeed she ever did think of anything but her work. Whether she admired him or hated the sight of him he had no idea, and while he didn’t particularly care, he would have been interested to know. But she was an admirable machine, and to her he owed a great deal of his clerical efficiency.

Methodically he began to work through the letters. Here was one from Messrs. Hooper of Liverpool, trying to excuse themselves for having supplied mouldy nuts for the monkeys and certain birds, and offering to accept a slight reduction on the price. “Not a bit of it,” Surridge commented. “They can take their damned stuff away and send more, or else they can do without our custom. There’s illness enough as it is among the monkeys.”

He passed over the letter, knowing that in due course a document would be laid before him beginning: “With reference to your communication of 15th inst., I regret to inform you,” and so on. When Miss Hepworth had first come she would have inserted the words “esteemed” before “communication,” and “duly to hand” after “15th inst.”, but he had managed to break her of these. He could not, however, make her alter the sweep of her gambit, nor even get her to substitute the word “letter” for “communication.”

The next letter was from the Liverpool agents of the Purple Star Steamship Company, and read: “We beg to advise you that we are expecting our S.S. Delhi to berth in the Ambleside Dock, Liverpool, at 7.0 a.m. on Friday morning, 24th inst. with the two elephants consigned to you, and referred to in our LST of 7th inst. We shall be obliged if you will kindly arrange to take delivery as soon after that hour as possible.”

This matter George had already dealt with. Transport of elephants through England was rather a job. They were too big to send by rail, and it would have cost a considerable sum to fit up a road lorry to take them. The elephants would therefore have to walk the hundred odd miles to Birmington. They would take it in easy stages and he had arranged for sheds for them to sleep in each night. Two Indian keepers had travelled with them, and he was sending his own man, Ali, with a couple of assistants to render help in case of need.

A number of letters covered ordinary routine matters. In these food bulked large. Coarse meat for the larger carnivora was easy to obtain, but in the winter the large amount of green food required for the vegetarian creatures was more of a problem. The quantities of certain articles of diet were enormous. Fish ran into some dozens of tons per annum. Each king penguin alone ate some dozen herring every day, and on occasion would take twice this number at a single meal without turning a feather. Eggs, bread, milk, fruit, all ran into astronomical figures, and all must be of good quality and quite fresh. The catering department was in itself a full time job, and George had an assistant to carry on the routine work. But all new or large contracts he supervised himself.

Then there were letters from people who wanted to get rid of pets—or rather of creatures which had been pets—and thought the Birmington Zoo a suitable dumping ground. Adolescent bears were frequently on offer. Bought as small and enticing balls of fur, they had the drawback that they grew, eventually becoming an embarrassing and overwhelming charge. People who brought home monkeys from abroad and who had their most cherished possessions torn into shreds, or were bitten to the bone, came to the opinion that a monkey in the Zoo was worth two in the hand. Other people wrote asking questions about animals: “My daughter has been given a pair of Belgian hares. What do you consider their most nutritive diet?” With all these and many more, George dealt quickly.

After the letters there were interviews. Keepers came in with reports on all kinds of matters, mostly in response to a call, but occasionally on their own initiative, if they considered their business important enough to go before the “Chief.” The health of various sick animals was discussed, as well as methods of dealing with tantrums or notions which others had taken. Repairs to buildings were noted, with ideas for alterations or improvements. The gardener had a scheme for next year’s planting and touched on a vexed question of some standing: whether or not the gravel walks should be replaced with asphalte. Gradually George built up his list of the points to which he must give special attention during his daily inspection, which was now shortly due.

“That all?” he said at last.

“John Cochrane is waiting to see you.” Miss Hepworth’s tone held a distinct reproof that he should have forgotten the interview.

But George had not forgotten it. This was one of those cases he loathed dealing with, and now he braced himself for an unpleasant ten minutes. “Send him in,” he directed and there entered a small wiry man of about fifty, with a sallow face and downcast expression.

Cochrane was a night watchman and had been employed for some six years. He was a good average man, sober and careful, and until the present matter arose, George would have said quite reliable. Up till now he had never been “before” George, but had done his work unobtrusively and, so far as was known to the contrary, well. Unhappily, in this paragon a yellow streak had now been discovered.

It happened that a week earlier Surridge had been up in London and had missed his usual return train. Instead of reaching Birmington at 11.0 p.m. he did not arrive till 3.0 in the morning. It also happened that either because of there being more passengers than usual or fewer taxis, he found himself able only to share a vehicle, and that for only part of his way home. Half a mile from the Zoo he got out, intending to walk the rest of the way.

As he turned a street corner he all but ran into a man who was coming to meet him. The man quickly put his hand over his face. But he was too slow: George had recognised him.

“What are you doing here, Cochrane?” he asked. “Have you got leave from duty?”

Cochrane was so much taken aback that he could scarcely speak. Then he admitted that he had left his work without either obtaining leave or putting someone else in his place. George suspended him and told him to call and see him next morning.

The man’s statement next day seemed straightforward and George believed it. He said his wife was ill and had been ordered medicine every four hours day and night. She could not get it for herself and during the day he had been able to attend on her. For the night he could not afford a nurse, but he had paid a neighbour a few shillings a week to look after her during his turn of duty. On the previous night the woman had been called unexpectedly from home. As soon as he had heard of this he had tried to get a substitute, but without success. He had decided, wrongly, he now admitted, to slip home in the middle of his nine hours watching, give her her medicine, and return as quickly as possible. He lived within a couple of miles of the Zoo and did not expect to be absent for more than an hour at the outside.

George was distressed about the affair, but the more he thought over it, the more serious the fault appeared. He saw that as director he could not consider the man’s home circumstances, but only his duty to his employers. If fire had broken out the results might have been disastrous. Not only might there have been heavy financial loss, but dangerous animals might have escaped and people might have been killed. He told Cochrane that he would consult his Chairman on the matter, but that he had no hope that the latter would agree to his being kept on, and that he ought to look out for another job.

George had taken the trouble to find the doctor who was attending Mrs. Cochrane to check the man’s story. It proved to be Dr. Marr, a friend of his own, who lived close by. Marr confirmed the details of the case.

“I’m sorry if he’s going to lose his job,” the doctor went on. “Though he’s a man I don’t personally get on with—bad manner, you know—the family is decent. Mrs. Cochrane is a really good sort of woman and the son and daughter are doing well. The daughter’s in service with the Burnabys: you must have seen her scores of times, and the son has a fairly good job at a garage.”

The Burnabys, father and daughter, also lived close to the Zoo and were friends of the Surridges. Surridge had often noticed the maid, and now that his attention had been called to the matter, he saw that she was like her father. His own feeling was that after a week’s suspension Cochrane might be re-started, but when he discussed the affair with his chairman, Colonel Kirkman, he found him adamant. A man who had so abused a position of trust could not be kept. If the medicine were so important, Cochrane’s course was obvious. He should have seen his immediate superior and had proper arrangements made for his relief.

“We’re not unreasonable people,” Kirkman went on. “If he had asked for leave he would have got it. I don’t see, Surridge, that you can possibly keep him. The Committee wouldn’t stand for it.” Cochrane had remained suspended since the incident, and it was to pass on this verdict that George had now asked him to call.

The interview was even more unpleasant than George had anticipated. Cochrane took the news badly. He spoke very bitterly, but George couldn’t help himself.

“I’m sorry, Cochrane,” he concluded. “When you think the thing over you’ll see that I have had no alternative. There’s some money due to you, and if you go to Mr. Harley you’ll get it. And I may say that if in a private capacity I can help you to a job, I’ll be glad to do it.”

The question of the man’s successor would have to be settled without delay, but he decided to postpone it for the moment, as Renshaw, his chief assistant, was waiting to accompany him on the daily inspection.

The Zoo was in process of transformation from the old-fashioned arrangement, in which the houses of the various exhibits were massed together with small barred pens attached to each, to a modern layout, with larger areas for the animals, reproducing as far as possible their natural surroundings. An adjoining estate of twenty acres had recently been added to the old four-acre park, and the new houses were being built and the animals moved into them as finances permitted. George was very keen on this work and had infected the staff with his enthusiasm.

The main walk already referred to, still however remained the centre of interest. On its right were five blocks of buildings containing respectively the elephants, certain large cats such as pumas, jaguars and cheetahs, the tigers, and the lions. Behind these houses was an area of garden with three pools, for polar bears, penguins and seals. At the other side of the pools were seven more houses, for snakes, small Indian animals, small monkeys, large monkeys, camels, dromedaries, and rhinoceroses respectively. The arrangement was like a D, where the five houses along the walk were represented by the vertical line, the pools by the central area, and the other houses by the curved back. Of these latter, the snake-house was nearest Surridge’s office at the top of the D, and between the monkey-houses—that is, half-way round the curved side—there was a small private door leading out to an adjoining road. This was not used by the public and was always kept locked.

It was Surridge’s custom to begin his inspection with the snakehouse, work down the curved side of the D, and so on to the other houses. The collection of snakes was extremely good, one of the best features of the Zoo. There were two immense anacondas, constrictors not far from twenty-five feet long and each capable of swallowing a small sheep at a meal. There were English adders, and the dreaded puff adders from South Africa. There were brown snakes, black snakes, green snakes and yellow snakes, whip snakes, cobras and rattle snakes. There were a pair of ringhals, appalling reptiles which can shoot a jet of poison from ten feet away, unerringly reaching their victim’s eyes, as well as many harmless and beautifully marked creatures. All seemed to Surridge in good condition. Whether there was something that suited them in the air or soil of Birmington, or whether their health was due to the care of their attendant, Keeper Nesbit, Surridge did not know, but he secretly believed that Birmington had more success with its snakes than any other zoo in the world.

It was for this reason that the Burnabys, with whom the dismissed watchman’s daughter was in service, had come to the district. Burnaby had been professor of pathology at Leeds University, from which position he had recently retired. During the latter part of his life he had specialised on the use of snake poisons in treating various diseases, and he had been looking forward for years to the time when he could retire and write his magnum opus, the book descriptive of his researches, which would make him famous. Wishing to continue his investigations, and knowing the reputation of the Birmington Zoo for its snakes, he had asked George for special facilities to experiment with his collection, and these George, with the approval of his committee, had granted. The old man had thereupon bought a house close by, fitted up a laboratory, and with his daughter to keep house for him, had settled down to work. He had even been granted keys to the snake-house and some of the cages, as well as to the private side door, which latter saved him a long walk round through the main entrance.

Surridge and Renshaw passed on to the small Indian animals and from them to the monkeys. Here things were not so satisfactory as in the snake-house. A lot of monkeys had been ill lately with something like flu. A marmoset and a lemur had died, and one or two others seemed in an unsatisfactory way. Both men were worried about the affair.

“If there’s not an all round improvement by the end of the week I’ll wire for Hibbert,” Surridge said, referring to the calling in for consultation of the chief medical officer attached to the London Zoo, a matter which they had already discussed. “No reflection on you, of course. But I think we should have a second opinion.”

“I should welcome it,” Renshaw agreed.

They passed on, continuing their round, dealing with the hundred and one matters which in a place of such size are continually arising. Then Surridge returned to his office, and for the hour still remaining before lunch, settled down to get out his monthly report for the next meeting of his committee.

For some years he had given up going home in the middle of the day, lunching instead down town at his club. Ostensibly this was for the sake of his business: to keep in touch with the other men of the city and be au fait with what was going on. Really his motive was quite different. The society of his wife had become a strain and he was glad of any excuse to avoid being with her. He believed she also liked the arrangement, partly for the same reason as his own, and partly because it left her freer and saved trouble in the house.

Presently he left the office to walk the half mile or more to the club. He usually went with a man named Mornington, an artist who lived near the Zoo and whose work, being carried on exclusively at his home, left him in need of the society of his fellows. But to-day there was no sign of Mornington, and George went on alone.

As he walked his thoughts reverted to his own circumstances. The question of money was growing more and more pressing. He would have to do something about it, something drastic. He could give up his play of course, but he didn’t want to do that unless it proved absolutely unavoidable. It was not so much for the excitement of the gambling, though he enjoyed that, as for the companionship. An even more important reason was that he now owed a considerable sum. If he stopped playing he would inevitably have to find that money, whereas a run of luck on one evening might clear him. This had occurred already on three separate occasions, on each of which he had won back a pretty considerable amount. There was no reason why the same thing should not happen again. If, and when, it did, that would be the time to stop.

Then there was his aunt’s legacy. He did not know what she was worth, but it must be several thousand: say seven or eight thousand at the most moderate estimate. And at her death he would get most of it—she had told him so. What, he wondered, would his share amount to? After death duties were deducted and one or two small legacies to servants were paid, there should be at least five thousand over. Five thousand! What could he not do with five thousand? Not only would it clear him of debt, but he could get that blessed car for Clarissa as well as several other things she wanted. They could take a really decent holiday; she had friends in California whom she wished to see, and for professional reasons he had always wanted to visit South Africa. In countless ways the friction and strain would be taken from his home life. And all this he would get if only the old lady were to die! Last night she had looked particularly ill; pale like parchment and more feeble and depressed than he ever remembered having seen her. Again he told himself that he didn’t wish her harm, but it was folly not to recognise facts. Her death was the one thing that would set him on his feet.

It happened that the first person he saw in the club was Dr. Marr. Marr was a man of about fifty, tall and spare, with a look of competence and a kindly smile, which when it broke out transformed his rather severe face, making it radiate good will. He was a general favourite, particularly, George had heard, among his panel patients.

George had often compared their lives, which in most respects were a complete contrast. Marr was happy at home: Margaret Marr was one of the salt of the earth. He had a big practice and seemed to have plenty of money, though George in fairness admitted that he worked for it. Also he held certain official positions, including that of police doctor for the district. He never lunched at the club when he could avoid it, preferring his home to all other places upon earth.

“Unexpected seeing you here,” Surridge greeted him.

“I know,” returned the doctor. “I’m lunching Ormsby-Lane. Down from London for a consultation. What’s the best news with you? Have you sacked that poor devil Cochrane?”

They talked over the case for a few moments, while George wondered how he could introduce the subject of his aunt, whom he knew Marr attended. He had to be careful about what he said. It must not look as if he were thinking too much of the old lady’s money.

Then Marr himself gave him an opportunity. “I didn’t see you last night at Cooper’s lecture on his Sinai excavations,” he observed. “Interesting stuff and fine pictures.”

“I should have liked to go,” George returned, “but I couldn’t. We had the aunt to dinner: Miss Pentland, you know.”

“Oh, yes. I was out seeing her a couple of days ago.”

George hastened to improve the occasion. “I hope it was only a social call? She seemed a little tired last night, though not exactly ill.”

The doctor shrugged. “Well, she’s getting on in years, you know.” He paused, shook his head, then changed the subject.

George’s heart gave a leap. Marr, he knew, was if anything an optimist, and such a remark in such a connection could surely mean only one thing. Her doctor also thought Lucy Pentland’s health was failing. George longed to press for more definite information, but while he was weighing the pros and cons the opportunity passed. Marr interrupted himself in the middle of a sentence. “There’s Ormsby-Lane,” he exclaimed. “Excuse me, old man, I must go and meet him.”

Lunch passed without further incident, and after a chat in the smoking-room, George returned to his office. Frequently he had to pay calls in the city at this hour, and twice a week he played a round of golf, but on this occasion there was no such engagement and he walked back with the artist, Mornington.

There was plenty of work to keep him busy all the afternoon: reports, statistics, estimates to be prepared, technical articles in the journals to be read. Also he was doing a paper for the Zoological Society on the effect of environment on animals in captivity, and he wanted to arrange the notes he had already collected.

In spite of this, he could not keep Marr’s remark, and particularly Marr’s gesture, out of his mind. From an optimist they certainly did look significant. Marr, he would stake his life, thought badly of his patient. And he, George, was medically no fool. In qualifying as a vet he had learnt a lot about human ailments. He could see for himself that quite unmistakably the old lady was going down the hill...

And that would mean—five thousand pounds!