Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Robin Lloyd-Jones has been exploring the west coast and islands of Scotland in his sea kayak for more than forty years. In this book he recalls many a memorable expedition to wild and beautiful shores. Amongst magnificent scenery and ever-changing seas, we are transported to Jura, Scarba, the Garvellach Isles, Mull, Staffa, the Treshnish Isles, the Monach Isles, Iona, Lewis and the Uists, Skye, the Orkneys, and the Shetland Isles. Along the way, he explains a great deal about kayaking, about the wildlife and history of the areas he visits. More than that, however, he makes us feel that we are with him in his kayak. Through his vivid and beautifully crafted prose, we experience the terror of a force nine gale, the tranquillity of moonlit trips, and the lure of tiny bays and seal-meadows accessible only to a slim kayak. We encounter dolphins, otters, unidentified monsters and nuclear submarines. This is a book to set the imagination adrift and appeal to the Robinson Crusoe in all of us; a book for those seeking wider horizons, be their vessel an armchair or a kayak.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 331

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

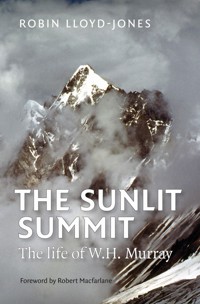

Robin Lloyd-Jones grew up in India and studied at Cambridge. He has served as President of the Scottish Association of Writers (1993–1996) and the Scottish Branch of PEN International (1997– 2000) and has also taught Creative Writing at Glasgow University. His book The Sunlit Summit was Saltire Society Research Book of the Year Award in 2013 and his novel The Dreamhouse was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1985.

Other books by Robin Lloyd-Jones

Fiction

Red Fox Running (Anderson Press, 2007)

Fallen Angels (Canongate, 1992)

The Dreamhouse (Hutchinson, 1985)

Lord of the Dance (Gollancz and Arena, 1983)

Where the Forest and Garden Meet (Kestrel, 1980)

Non-fiction

Fallen Pieces of the Moon (Whittles Publishing, 2006)

Scottish Wilderness Connections (Rymour Books, 2021)

The New Frontier (Thunder Point Publishing, 2019)

Autumn Voices (Play Space Publishing, 2018)

The Sunlit Summit (Sandstone Press, 2013)

Radio Drama

Rainmaker (BBC radio drama, 1997)

Ice in Wonderland (BBC radio drama, 1993)

This edition published in 2022 by

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Robin Lloyd-Jones 1989, 2022

First published in 1989 by Diadem Books as Argonauts of the Western IslesSubsequently published by Whittles Publishing

This edition published under licence from Whittles Publishing

The right of Robin Lloyd-Jones to be identified as theauthor of this work has been asserted by him in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means,electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78885 310 1

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is availableon request from the British Library

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managedforests and other responsible sources

Typeset by Hewer Text UK, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

1 The Start Of A Long Affair

2 Readiness is All . . . Well, Almost All

3 The Best Part of a Goodish Bit

4 A Depe Holepoole

5 Mad Goats and Welshmen Go Out in the Midnight Moon

6 The Music of the Sea

7 Paddy’s Milestone

8 Iron and Gold

9 Never on a Sunday

10 Journey to the Moon

11 Bleached Bones and Bothy Rats

12 Towards the Land of the Ever Young

13 The Stolen Hours

14 Here Sea Monsters and Sundry Miracles Abound

15 A Born-again Canoeist

16 Mull Broth

17 Blazing Socks

18 Gale Force from the Garvellachs

19 A Chorus of Islands

20 Speed, Bonnie Boat

21 Dreamcatcher

22 The Realms Of Night

23 Other Worlds Are Possible

Postscript

List of Maps

1 The Western Isles of Scotland

2 The Garvellachs, Scarba and Surrounding Islands

3 The Ardnamurchan Peninsula, Mull and Surrounding Isles

4 The Isle of Lewis

5 The Uists and Monach Isles

6 The Orkney Islands

7 The Isle of Skye, Raasay and Surrounding Islands

8 The Isle of Gigha

9 The Shetland Islands

Introduction

Argonauts of the Western Isles was first published in 1989 by Diadem Books. Then, in 2008, Whittles Publishing put out an edition containing an extra five chapters covering my kayaking adventures on the Scottish west coast since the original version. With the addition of some fresh photographs, this current edition by Birlinn has the same content as the 2008 version, but is in a smaller, more compact format and with the slightly different title of Argonauts of the Scottish Isles. The fact that the book has not been out of print for over thirty years says much for the lure of Scotland’s remote islands and wild shores. It is my hope that this latest edition will introduce new generations to the adventure and joy to be had in these wilderness places.

Readers should bear in mind that some of the adventures described in the early chapters might be nearly sixty years in the past. When you read the word ‘now’, it refers to a historical kind of now. Equipment and techniques have changed over the years and much of the advice offered in the earlier chapters is out of date. However, I have not altered any of this because I think there is value in letting it stand as a record of how things used to be done. In the intervening years there has been a much greater emphasis on safety. There are parts which at the time seemed like grand adventures, but now read more like cautionary tales.

One obvious change is that there is a lot more sea kayaking being done these days. Kayaks on top of a car used to be an unusual sight. Now you see them everywhere. New and more efficient kayaks and paddles, improved clothing, instant tidal predictions off the Internet, and satellite navigation have all made life easier. I am amazed at the discomfort I was prepared to put up with in the old days. Better equipment has helped push up the standards of performance. So too has the coaching efforts of the kayak clubs, assisted by the British Canoe Union and the Scottish Canoe Association. Routes which were regarded as fairly advanced in days of yore are all in a day’s work for the average modern paddler. And talking of changes – like the mountains, which for some strange geological reason are becoming steeper with the passing years, I’m sure the sea is getting colder and my kayak heavier!

Most of the places described I have returned to several times over. Each time is a new experience. The weather, the tide, my companions are different, and I myself see things through different eyes. I visit the wreck of the Captayanis regularly. Like me, it gets a little rustier each year.

I would like to thank my friends Archie, Martin, Michael, Ian and Colin, whose companionship has doubled the pleasure of all those miles paddled. My profound gratitude goes to all the moments and places recorded in this book and the many unrecorded incidents too which have refreshed and recharged me in body and spirit.

I will end by quoting from the Preface to the 1989 edition. With the environment increasingly under threat and now that I have grandchildren, the words mean even more to me than before:

In spreading the word about remote and beautiful spots am I hastening their destruction? I think not. Those who reach them using only paddle or sail have experienced a closeness to nature. They know such riches are worth preserving. It is my hope that this book will increase the number of voices in favour of conservation so that the islands and coasts I describe are still unspoilt when our children’s children beach their kayaks on their shores.

Robin Lloyd-Jones

Helensburgh

January 2022

Chapter 1

The Start Of A Long Affair

Induction and training

When I was five years old, my aunt, recently returned from Canada, assured me that Red Indians parted their hair down the middle in order to balance their canoes. From that day on I had been quite convinced canoes were tippy, unreliable things. So, years later in the 1960s, I was dismayed to find myself taking part in a canoe expedition. Under the impression that I was the instructor of mountaineering, camping and general hillcraft, I had arrived at the Outward Bound Moray Sea School near Elgin in Scotland only to be told that I was scheduled to lead a group on a grand circular expedition which included not only a four-day walk across the Cairngorms (never seeing more than about ten feet ahead of us the whole time because of thick mist), but also 100 miles of cycling, a journey in small boats up the west coast, the rounding of Cape Wrath in the sail-training ship the Prince Louis and a canoe trip from one side of Scotland to the other via the Caledonian Canal which links the Moray Firth on the east coast to Loch Linnhe on the west coast by way of Loch Ness, Loch Oich and Loch Lochy. ‘But I’ve never sat in a canoe in my life!’ I protested. ‘If you’re officer material you can lead anything,’ was the reply. Another favourite saying of the course commandant was, ‘Instructors are expendable, punters aren’t.’ Like an eighteen-inch welly boot in nineteen inches of water, I was filled with cold dread at the thought of being expended in one of those dangerous vessels. The leader was really a ‘punter’ in disguise. The expedition was preceded by ten days of training, much of which was aimed at fostering teamwork. For this reason all the canoeing was done in double canoes and the rescue drills were specially designed to involve the whole group. In retrospect, I realise I didn’t learn much that was subsequently of use to me as a reasonably serious sea kayakist, but it whetted my appetite. I had felt the bows lift to a wave, I had felt the sea rolling beneath me and become part of its rhythm. Sitting a few inches below its surface, separated from it only by the thickness of a skin, I experienced an intimacy with the ocean I had known in no other craft – every wave individual, every motion communicated, man and sea with a minimum of technology between. In short, I was hooked for life.

They say that camping is the severest test a marriage can undergo. Couples still wishing to prove a point should try a longish trip in a double canoe. The guy in the bows becomes convinced he is doing all the graft, imagines his partner behind him sitting back enjoying the scenery. Meanwhile, the fellow in the stern is working up a real hatred for the back of the neck and the silly ears which, mile after mile, have been blocking his view, and for the stupid owner of them who is setting a pace that is either too fast or too slow and who is obviously to blame for the fact that the two paddles keep clashing. Not surprising, therefore, that halfway up Loch Lochy one of our group suddenly let out an anguished cry, stood up in the canoe and brought his paddle down on the head of his unsuspecting partner.

Shortly after this summer holiday job as an instructor, I changed schools and took up a new teaching post in Helensburgh, a seaside town on the Firth of Clyde. The house which I shared with my wife, three children and six cats was on the water’s edge. When the tide was up the sea was only two feet away from the end of the garden – ideal for canoeing. Furthermore, the new school, Hermitage Academy, had amongst its staff a compatible soul, an art teacher named Archie. What neither of us had was a canoe, nor the money to buy even second-hand ones or kits. Then, one lunch hour, we decided to sunbathe on the roof of the four-storey school building. Archie had found a way up to it and a key that fitted a locked door. In a corner of the flat roof, sheets of discarded asphalt material were hiding something. If the thickly made fibreglass effort we uncovered wasn’t a bath it must be a double canoe. Together we could hardly lift it. Then, as we removed more of the asphalt, we came across two single kayaks. One was a wooden framework with a thin PVC material stretched over it. Its ribs were fractured, its skin cut and torn. Archie fingered the shiny, wet-look PVC.

‘You’re the kinky one, this had better be yours.’

The other had been assembled, none too expertly, from a plywood kit. It too was holed and splintered.

Nobody seemed to know anything about the canoes or care whether we made use of them or not. So, the next day, with the aid of our climbing ropes, we lowered the two singles over the edge. Unfortunately, the kinky canoe took a dive from two storeys up onto the tarmac below.

‘This puts Cilla Black’s nose-job in the shade!’ Archie commented.

Several weeks and a great deal of repairing later, came the moment of the launch from the end of my garden. We wore windproof anoraks, T-shirts, shorts and canvas shoes. Welly boots, I had read somewhere, were dangerous, they could fill up with water and drag you down. It was several years before I questioned this myth, several years of canoeing with wet feet quite unnecessarily. For life jackets we sported thick kapok things which had come from the lifeboat of some liner which was being dismantled in the breakers’ yard at Faslane on the nearby Gareloch. Sallie, my wife, kissed the patched bows of my kayak. Archie struck a heroic pose, raised a bottle of whisky and quoted:

The sea wants to know – not the size of your ship,Nor built with what art;

Nor how big is your crew, nor your plans for the trip

But how big is your heart.

We took a slug each, then lifted our craft into the water.

I, of course, was the expert. That is to say, I had actually been in a canoe before. I showed Archie how to get in by sitting on the stern with the homemade paddle out to one side as a stabiliser. We wobbled out into Helensburgh Bay, getting used to the feel and balance of our kayaks. Novice and complete beginner though we were, in fact, we possessed already a fair amount of relevant skills and knowledge. My father had been a keen yachtsman, keeping a boat in Dartmouth and sailing to places like the Channel Isles, Cherbourg, the Isle of Wight. I knew something about the habits of the sea, the tides, a little about navigation and charts and I was used to having an oar in my hand. It still takes me by surprise when I encounter learners in a canoe who haven’t grasped the basic principle of which side you paddle if you want to turn, or that paddling in reverse produces the opposite effect.

Archie, too, had grown up near the sea and was used to the ways of small boats. And both of us were mountaineers. We knew about hypothermia and the general clothing and calorie needs of the body in hard outdoor situations; we knew about camping and compass work; and we knew that safety and survival were matters to be taken seriously. Above all, through mountaineering, we had discovered the satisfaction of accepting the challenges posed by rugged terrain or difficult natural conditions, of being self-reliant, the joys of exploration, the magnificence of wild and lonely places, the fulfilment and refreshment of spirit that a day in such an environment can bring. To us, these two old and much-repaired kayaks were a means to an end, a means of reaching further into the unspoilt places, of extending these kinds of experience, of getting to know the sea in the same way that we knew the ever-changing moods of the mountains of Scotland, and of journeying in one of the most exciting zones the earth can offer – the zone where the elements of land and sea perpetually war with each other.

People enjoy canoeing for reasons ranging from masochism (or is it machoism?) to communion with the gods. Although I have certainly found satisfaction in mastering the techniques and in being able to match my skill and training against the forces of nature, the end rather than the means has always remained the most important thing to me. Whatever your reasons, finding like-minded companions is essential and, in Archie, I had found someone whose attitudes and motivation exactly matched my own. Not that any of this would have been apparent from that first hesitant circumnavigation of Helensburgh Bay. Somewhere out in the middle of the bay Archie said, ‘What about buoyancy?’

‘What?’

‘I doubt if the natural buoyancy of either of these is sufficient for them to keep afloat if they fill up with water.’

‘My God! I never thought of that! Quick! Part your hair down the middle!’

Ever since then I have always checked any canoes in my group to make sure there’s something in bow and stern – air bags, old life jackets, blocks of polystyrene, well-capped empty plastic bottles – to keep them afloat. It’s amazing how the obvious can be overlooked.

The following weekend we decided on a rather longer trip, but one which we thought would be much safer since it was down the placid river Leven, with neither bank too far away. In its own way, it turned out to be a trip full of hazards. The plan was to launch about eight miles upriver at Balloch where the Leven flows out of Loch Lomond towards Dumbarton on the tidal estuary of the Clyde. The first hazard was a group of teenagers in hired dinghies with outboard motors who decided to ‘buzz’ us. Disdainful unconcern failed. Plan B was to beat it as fast as possible. It was a question of which overheated first, their puny put-put engines or us. Luckily their time must have been up because they suddenly turned round and headed back to Balloch.

Then came a stretch of countryside and, in a particularly shallow section, a herd of cows, knee-deep – do cows have knees? – blocking our way.

‘Just think of them as slalom gates,’ Archie said, heading for the underbelly of a fat Friesian. I wish, for the sake of the story, I could say that he passed between its legs, or that we were holed by a pair of longhorns. The best I can say is that, in a sea kayak, you expect the odd dropping from a seabird to defile your deck, but not . . . Anyway, my death-wish for some kind of spectacular holing was fulfilled by a submerged reef of rusty bedsteads. On the bank I taped up the rip in my PVC while Archie held at bay the pack of wild dogs that run free on most housing estates in these parts.

Hardly had we got going again when a horde of pint-sized cowboys ran along the bank, whipping imaginary horses and pointing sticks at us while making firing-type noises and shouting, ‘The last of the Mohicans!’

Stupidly, I raised my paddle as if it were a bow and loosed off a few arrows at them. The response to this was a hail of stones, nothing imaginary about them. This fusillade was maintained for several hundred yards until the two Mohicans finally outstripped them.

There remained the hazard of the bridges. At the first bridge we could be seen approaching from a long way off.

‘Bombs away!’ someone shouted.

The bricks narrowly missed us, sending up columns of spray as in Sink the Bismarck. The second bridge was soon after a bend and we were merely spat upon. By the third bridge we were sadder and wiser men, paddling slowly till the last moment, then spurting with a change of angle as we passed beneath it. The fourth and last bridge contained an unexpected surprise. There was a small waterfall where there hadn’t been one when I did my reconnaissance – the difference between the level of the river and the tidal waters beyond at high and low water. Allowing ourselves to be swept over the three-foot drop we drifted to the quayside where our pick-up car awaited us.

The Western Isles of Scotland

‘Stick to the sea,’ Archie said. ‘Come wind, come storm, it’s safer!’

Our trips became longer, but always remained within the comparatively sheltered waters of the Clyde Estuary and its adjoining sea lochs. We realised the benefits of spray decks which, worn like skirts and fitted over the cockpit, keep out breaking waves and keep in body heat; and we discovered that a good footrest makes all the difference to paddling – a solid base enabling the whole weight of the body to be put into the stroke. As with most people unused to paddling, it took both of us a while to appreciate that the pushing muscles of the arm, shoulder and back are stronger than the pulling muscles and that paddling is more a matter of punching the raised blade forward than of pulling the lower blade back through the water. And we discarded our bulky life jackets for slimmer borrowed ones, more appropriate to paddling, which could be inflated if required. Incidentally, occasionally I observe novices fully inflating their life jackets at the start of an outing. This is not advisable, not only because they are then too bulky for comfortable paddling, but also because, in the event of a capsize, that amount of buoyancy can press a person hard up against the underside of the canoe, making exit difficult. The proper time to inflate it is once you’re out of the canoe and a long wait in the water seems likely. Strictly speaking, this type of jacket is a buoyancy aid until it is inflated and only then does it become a life jacket capable of supporting the head of an unconscious person above the waves. There’s a rather grim joke that the difference between a buoyancy aid and a life jacket is that with the latter your dead body is still afloat when it’s found.

Once we felt reasonably competent, Archie and I went to our headmaster and asked for funds to start a canoe club in the school. He agreed, on the condition that we went on an approved course and gained our proficiency certificates and instructor’s certificates for sea kayaking. The education authority would pay the cost. Thus it was that we found ourselves at the Inverclyde National Recreation Centre at Largs on the Ayrshire coast, on one of the regular courses for the proficiency certificate run by the Scottish Canoe Association.

The course was quite an eye-opener. The less you know the less you realise how much more there is to know. Socrates is reputed to have said that he was the wisest person in the world because he alone knew that he knew nothing. Well, for us, this was the beginning of wisdom. For a start, we were in kayaks that performed so much better than our own, that behaved better in crosswinds and running seas and manoeuvred more easily. Up till this point, a kayak was just a kayak. Now we saw that its design was an important consideration. And then there were the deep-water rescue techniques for getting a capsized person back into his or her kayak. It came home to me that, prior to this, my notion of what to do had been very inadequate indeed. Had either Archie or myself capsized in deep, rough water before going on this course we could well have been in a lot of trouble. It seems incredible now, but neither of us had thought to try out a rescue in shallow water. We had assumed that, if an emergency arose, we would muddle through somehow. Maybe Archie had more faith in me as ‘the expert’ than I deserved. Another revelation was the whole range of support strokes and draw strokes. I’d had no idea that it was possible to lean on the water with your paddle blade and to push yourself upright again or to make a canoe move sideways. Ian, our instructor, demonstrated that it was possible to lean the canoe over until his ear was in the water and still recover to an upright position. He also demonstrated rolling a kayak. This was not part of the course, but I decided that I would make every effort to master the art as soon as possible. The most valuable thing I learned from Ian was that brute strength is never a substitute for good technique. A seven-stone woman, with good technique, should be able to empty and right a canoe with a hundredweight or more of water in it. With good technique and timing one can roll up a fully laden kayak almost effortlessly.

Whilst trying all these new strokes, I was averaging about five capsizes a day.

‘Stick to the sea, it’s safer!’ Archie would shout every time my head emerged above the waves.

‘It’s the ones who aren’t capsizing that I worry about,’ Ian said. ‘It means they’re being too timid, they’re not pushing themselves to the limit, not trying to extend themselves.’

‘What if I capsize during the test itself?’ I asked.

‘You won’t be penalised for trying too hard . . . as long as you come up smiling. It’s only the ones who break the surface with panic on their faces who are failed.’

‘As long as you come up smiling!’ became the catchphrase for the course.

This was before the days of kayaks with watertight compartments and bow and stern hatches, so the correct packing of a canoe for a camping trip was an important aspect of the certificate. Part of the test was to pack the kayak as for such a trip, with everything properly wrapped and protected against the sea, then paddle out and capsize. If, on landing, any item of gear was wet, you had failed.

It was like a catechism:

‘What is the correct order of packing your kayak?’

‘The things you need first go in last.’

‘Where does the first-aid kit go?’

‘In the cockpit directly behind your seat where you can reach it.’

‘And where do the spare matches go?’

‘In the centre of your sleeping bag or bedding roll.’

This last was always considered the ultimate in canoeing wisdom.

Towards the end of the course a friend of Ian’s, who lived locally, joined us for the day. He had brought along his logbook to show us the trips he’d made and the miles he’d paddled. One entry said, ‘Battery Pond, wind force four.’ The Battery Pond being an open-air swimming pool on the sea front!

This, too, became a catch-phrase with Archie and me. Whenever conditions looked a bit scary, one or other of us was bound to relieve the tension by shouting, ‘Battery Pond, wind force four!’ Certainly, it has been my experience over the years that some people who can perform all sorts of wonders and fancy strokes in a heated swimming pool cannot do them when it really counts: in the rough, cold sea, tired and in a fully laden canoe. Anyway, as far as the test was concerned, we both came up smiling.

Two weeks later, after some intensive practice, we were back again for another week’s course for the Instructor’s Certificate. This time we had the hallmarks of real canoeists: the hard corn in the groove between thumb and first finger where the paddle rotates in the hand, the tell-tale mark in the small of the back caused by the rear of the cockpit, the two worn patches on the outer heels of our canvas shoes, the result of paddling with feet splayed out. There were ten of us on the course. On the first day someone had to quit the course with severe sunburn. On the second day we lost another member of the group who capsized and came up unconscious. He had experienced a close encounter with a jellyfish and, unluckily, had proved to be allergic to its sting . . . On the third day a shoulder was dislocated. And now there were seven. We began to eye each other nervously like potential victims in an Agatha Christie play. On the fourth day one of our lot decided to take his own homemade fibreglass kayak out in rather blustery conditions. It had been made from a mould in two halves, the hull and the top deck being joined with strips of glass bandage and resin along the seam. Somewhere between Largs and Cumbrae Island, the two halves came apart and the kayak sank. And then there were six. In fact, the owner of the ‘collapsible’ canoe didn’t leave the course, but simply switched to one of the kayaks provided by the SCA. The real victim was Drew who had a tough time instructing such a mad bunch.

When it was my turn to have a go at instructing the others I got them all neatly lined up in their kayaks about twenty yards off the beach while I demonstrated some stroke or other. What was so amusing about my well-planned lesson? I wondered. I soon found out. A paddle steamer was passing close behind me. Its wash carried the lot of us way up the beach, leaving us high and dry.

Drew simply couldn’t get through to us that, instead of putting our heads down and paddling away like mad, we must develop the habit of continually looking around in all directions to see where everyone was, what shipping was approaching, etc. By way of making his point, he gradually dropped behind the group and then sneaked into a little bay. We were more than a mile on before anyone noticed.

I remember the visiting tester asking me, ‘There is a strong onshore wind. What would you do if a member of your group capsizes close to cliffs and is in danger of being smashed to pieces on the rocks?’

‘I wouldn’t have got into that situation in the first place,’ I replied.

I thought that was the only really responsible answer. The expected solution, however, was that you appoint the strongest paddlers in the group to use their towing lines to tow the capsized canoe and its unseated rider further out before going through the usual rescue drill.

I passed, all the same, as did Archie. Soon after that, with the help of Dave Whitelaw from Cumbernauld High School, we set up an evening class for making fibreglass kayaks. It was Dave’s own design, The Tern. Mine was yellow and curving at both ends. Archie wanted to name it the Banana, but I named it the Argo, after the ship in which Jason set out in search of the Golden Fleece.

‘We’ll be the Argonauts of the Western Isles,’ I said. And so, with new kayaks and newly found skills, we were ready, at last, for the major league. Well, almost ready.

Chapter 2

Readiness is All . . . Well, Almost All

Rough water training

To feel a tingle of excitement in every nerve, to feel adrenalin pumping through the body, to feel really alive, is a marvellous experience, but fear is something different, something ugly. No passion so effectually robs the mind of all its powers of acting and reasoning as fear. And the way to combat fear is through training. Knowing that you are prepared, that you can cope with the situation even if it gets worse, that you have something in reserve, that is what dispels fear. It has always seemed to me that plenty of practice is worth any amount of bravery. Courage, unless accompanied by competence and well-founded confidence, is merely foolhardiness. In my own preparations for the major league, two things in particular needed attention. Firstly, I had never sat in a cramped cockpit for more than two and a half hours without getting out of my kayak and stretching my legs. Perhaps this was due in part to the fact that, in the comparatively sheltered waters in which I had been canoeing, land was never too far away and there was never any real need to do a longer stint than that; and partly it was because, until I made a canoe for myself with a seat moulded to the shape of my own backside, I had been in such agony from pins and needles in the legs, numb bum and ‘the fidgets’ that to inflict more pain than was necessary upon myself would have been taking masochism too far. Even in a car, which is spacious by comparison, two or three hours can seem a long time. I knew, however, that many of the trips to which I aspired contained crossings of five hours or more, the capacity to deal with the ‘or more’ being a crucial factor in survival. Supposing one arrived at the other side and found it too rough to land? Or what if an adverse wind added another two or three hours onto the time it took? So I embarked on a programme of building up the distances paddled without landing. Helensburgh to Dunoon, a quarter of an hour on the beach for lunch and home again. Then, next time I would eat my lunch in my kayak twenty yards off the beach before paddling home again. And so on, gradually increasing both the mileage and the length between the breaks ashore.

Secondly, I wanted to be able to Eskimo-roll my canoe. These days it is an ability which is commonplace, youngsters can do it a hundred times non-stop using a table tennis bat instead of a paddle, or even with their hands alone. A quarter of a century ago, however, it was still a bit of a party piece, a trick that carried a certain prestige, something that somehow always managed to crop up casually in conversation if one could actually do it. There are dozens of different ways of rolling a canoe. The one I chose to teach myself, as being one of the easiest and also one of the most reliable for a heavy sea kayak, was the pawlatta. Basically, from the upside-down position, it is a long sweep of the paddle to one side of the kayak, from front to rear, which brings you halfway up, followed by a push with the flat of the blade on the surface and a rotation of the hips. A slim sea kayak is worn like a garment fitted from the hips and a great deal of the effective control of a kayak comes from the hips.

The drawings in the book I had borrowed from the library made it look easy. But when you’re upside-down, the ocean floor is where the sky used to be, everything that a few seconds ago was on your left is suddenly on your right and the top of your paddle blade has now become the underside. I spent weeks of practice in total disorientation, unable to figure out where the surface was, rolling myself further under rather than up, becoming increasingly bruised and battered by my contortions inside a kayak which seemed to be made of nothing but sharp projections and rough edges. My knees and shins were black and blue from being scraped and banged against the cockpit in countless hasty exits motivated by this unreasonable desire of mine to breathe in air rather than water.

At first I practised in shallow water about twenty yards off the end of my garden. When all else fails, the Irvine Push is a stroke to be recommended. It consists of placing one end of your paddle on the seabed and pushing yourself upright – so called because Irvine, on the Ayrshire coast, has a large area of shallow estuary and lots of cunning canoeists. I had not reckoned, however, on the kind folk of Helensburgh, who, on seeing someone thrashing and jerking about upside down in a canoe, invariably phoned the police or the local lifeboat. Tired of protesting that I didn’t want to be rescued, I took to paddling across to a remote bay on the other side of the estuary, where my only audience was a somewhat amazed seal.

Finally the day arrived when I managed ten successful rolls one after the other on the right-hand side, followed by another ten in quick succession on the left-hand side.

‘I can roll! I can roll!’ I shouted to the seal.

‘Ah, but can you do it in deep water?’ his sceptical expression seemed to say.

Out in the middle of the estuary, with nobody else in sight, the water looked so black, so deep, so cold. Supposing I tried a roll and failed? What would I do then?

I dithered, fussing with my spray deck. Was this going to be the story of my rock climbing all over again? On the practice boulders, a few feet above the ground, I could make moves on almost non-existent holds. I was a human fly. But a couple of hundred feet up, the same moves became impossible, unthinkable.

‘Which is it?’ said the seal inside my head. ‘Can you roll or can’t you?’

‘But it’s stupid to do it so far out, on my own.

‘Not if you’re certain you’re not going to fail.’

‘But . . .’

‘Well, do you have confidence in your own ability or don’t you?’

‘Yes, I do, I do!’

‘Prove it then.’

As I completed my roll, the seal whispered to me, ‘Maybe that was just a fluke. If you really believed in yourself you’d do it again.’

The next step was to be able to roll in rough, breaking water. One of the difficulties of this is that once the surface ceases to be flat and still, it is much harder to gauge where it is from the upside-down position. On one occasion, when the water was murky with churned up sediment, I became completely disorientated and unable to find the surface. I lost all sense of which way was up and which was down. I was running out of breath. What should I do? If I came out of the canoe how would I get back in again? Calm yourself, you’re getting it wrong because you’re panicking. I relaxed and as soon as I did so I could feel my paddle, of its own accord, solving the problem for me by naturally floating to the surface. On another occasion, I did a deliberate capsize amongst breaking surf and struck my head on a hidden boulder. I hung upside-down in a daze. There must be some mechanism in the brain which automatically closes down the breathing in situations like this. I only know that, without being aware of it, I didn’t try to breathe. I brought myself upright again, not by any conscious action, but because the drill was ingrained and automatic. After that, I always carried a crash helmet with me – the kind that lets water drain out of it – and put it on when going through surf or when I couldn’t tell what lay below the surface. I suppose what I should also have done was to stop going out on my own. But, with the sea lapping at the garden wall, whispering, calling to me . . .

Throughout the winter I practised in the school swimming pool. I practised remaining upside-down for a count of twenty before rolling up; I practised throwing my paddle away and, still inside my kayak, swimming to it and then rolling up; I practised coming out of the canoe, getting back into it again while it was upside down and rolling up. Then, with the approach of summer, I did it all over again in the rough, cold sea. And I discovered a minor irony along the way – that, once you can roll a sea kayak, your chances of having to do so in earnest are considerably reduced. In learning to Eskimo-roll you gain such mastery of the basic recovery strokes and control over the kayak that an involuntary capsize becomes an increasingly rare event. The very fact that you know you can do it gives you confidence. A relaxed and confident paddler is far more likely to remain the right way up than someone who is anxious and tense and does not have the confidence simply to let well-trained reflexes cope with things instinctively. When the going gets difficult, the best advice I can give to a companion – and the hardest to take – is, ‘Relax. Believe in the kayak and in yourself.’