Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

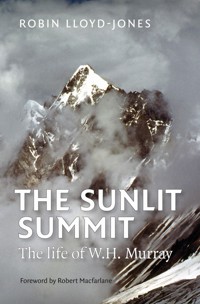

William Hutchison Murray (1913 - 1996) was one of Scotland's most distinguished climbers in the years before and after the Second World War. As a prisoner of war in Italy he wrote his first classic book, Mountaineering in Scotland, on rough toilet paper which was confiscated and destroyed by the Gestapo. The rewritten version was published in 1947 and followed by the, now, equally famous, Undiscovered Scotland. In 1951 he was depute leader to Eric Shipton on the Everest Reconnaissance Expedition, which discovered the eventual successful route which would be climbed by Hilary and Tensing. From the 1960s onwards he was heavily involved in conservation campaigns and his book, Highland Landscape, commissioned by the National Trust for Scotland, identified areas of outstanding beauty that should be protected. It proved to be extremely influential. In 1966 he was awarded an OBE as he pursued a life of service, as is well illustrated by the various posts he held: Commissioner for the Countryside Commission for Scotland (1968-1980); President of the Scottish Mountaineering Club (1962-1964) and of the Ramblers Association Scotland (1966-82); Chairman of Scottish Countryside Activities Council (1967-82); Vice-President of the Alpine Club (1971-72); President of Mountaineering Council of Scotland (1972-75). He was a prolific author but a proper understanding of his life and work requires that we appreciate that his driving force was a quest to achieve inner purification that would lead him to oneness with Truth and Beauty. For many years the climber, author and teacher, Robin Lloyd-Jones (above) has been researching the life and work of Bill Murray and working steadily on this biography. It is not only a triumph of fine writing and interest, but a worthy accolade for this great man.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 752

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE SUNLIT SUMMIT

The life of W.H. Murray

Robin Lloyd-Jones

Foreword by Robert Macfarlane

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Black & White

1. Murray on the Cioch in Skye. Ben Humble’s best-known photograph taken when there was still full daylight at 9 pm, June 1936.

2. This photo was taken on the same evening as Plate 1. Murray commented that Humble would spend hours trying to get the right shot.

3. Murray climbing in Skye with the Cioch below.

4. Murray (standing) with Rob Anderson on the Cuillin ridge, Skye. It was Anderson who drew the maps and diagrams for several of Murray’s books.

5. Murray, Douglas Laidlaw (sitting) and Dr J.H.B. Bell outside the CIC Hut during the exceptionally hot summer of 1940 that was overshadowed by war.

6. Part of the first page of Murray’s application to join the SMC. ‘Occupation’ has been left blank because, in 1945, Murray was still in the army and uncertain of his future.

7. A pre-war group outside Lagangarbh, Glencoe.

8. JMCS membership card, 1939. Murray’s address on the card is his mother’s house.

9. JMCS programme for 1937. The JMCS was at the centre of Murray’s climbing activities and of his social life.

10. Percy Unna in 1932. Unna, a former president of the SMC, was one of the NTS’ greatest benefactors and was passionate about keeping the mountains unspoiled.

11. Dr ‘Jimmy’ Bell who climbed frequently with Murray and whose exploits spanned the pre- and post-World War I years, linking with the newly formed JMCS and helping to keep Scottish climbing alive.

12. Tom Longstaff in the Alps, 1904. Murray greatly admired Longstaff and his uncompetitive attitude to mountaineering.

13. POWs at Chieti, Italy. Taken in 1942 at the same time as Murray was imprisoned there.

14. The first moment of freedom. A jeep of the American Ninth Army arriving at the gates of the Brunswick prison camp in Germany in the Spring of 1945.

15. 1950 Scottish Himalayan Expedition. Dotial porters carrying heavy loads at 18,000 feet to Camp 3 on Bethartoli Himal.

16. Gorges and rushing torrents sometimes gave way to calmer waters and time for contemplation.

17. Tea break during one of the many long treks through the Eastern Garhwal region of the Himalayas. Tom Weir holding up his mug.

18. The Sona glacier beneath one of the peaks of the Panch Chuli.

19. Dotial porter with the head of a goat which had been executed for a feast. Goats in this part of the Himalayas were also used as pack animals by the local people.

20. Loading a jhopa, a kind of yak, for the trek from Dunagiri to Malari. The agreed load for each jhopa was 160 pounds.

21. Camp 2 on the unsuccessful attempt to climb South Lampak Peak. Behind the tent is the 7,000-foot wall of Tirsuli. Note the evidence of a recent avalanche.

22. The Central Pinnacle at 18,000 feet on Uja Tirche. Murray, Scott, Weir and MacKinnon went on from there to make a first ascent of Uja Tirche’s North Ridge (20,350 feet).

23. ‘Number your red-letter days by camps, not by summits,’ Tom Longstaff wrote in a letter to Murray. In camp was where expeditions could relax, enjoy their surroundings and the company.

24. Payday for the porters. Murray at the table with Scott behind.

25. Murray wearing a monk-like cape at Darmaganga. Next to him is Douglas Scott.

26. This portrait of Murray, taken in a professional studio, was used on the cover of his autobiography.

27. 1951 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. From left to right: Eric Shipton, Michael Ward, Bill Murray, Tom Bourdillon.

28. Ang Tharkay, the head Sherpa who bartered with the Tibetan border guards west of Everest and saved Murray, Shipton and Ward from arrest and imprisonment.

29. Thyangboche Monastery where the 1951 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition stopped on their way to Mount Everest. Murray declared this to be the most beautiful place he had ever seen.

30. Hillary sees the Khombu glacier and the Western Basin from the flanks of Pumori, confirming that this might be a possible route up Everest.

31. Yeti footprints west of Everest, seen by Shipton’s group and then by Murray’s group two days later.

32. Sir John Hunt in conversation with Geoffrey Winthrop Young in 1953, soon after the former’s return from leading the expedition that made the first ascent of Everest.

Colour

1. The Cobbler, the first mountain Murray ever climbed, and where he and Ben Humble once completed 16 routes in one day.

2. The Buachaille Etive Mor, Murray’s favourite mountain where he climbed more frequently than anywhere else.

3. From left to right: Bill Mackenzie, Archie MacAlpine and Bill Murray on the summit of Ben Nevis, July 1937 after the third ascent of Rubicon Wall.

4. Final part of the Jericho Wall pitch of Clachaig Gully, Glencoe. Murray and his party made the first ascent in 1938. In this photo, taken 72 years later, Mike Cocker is leading.

5. Murray heading for SC Gully, Stob Coire Nan Lochain, Glencoe, in 1939.

6. Alasdair Cain, Graham Moss and Mark Diggins approaching Tower Gap in the 1994 film The Edge which was a re-creation of the 1939 winter ascent of Tower Ridge made by Murray, Bell and Laidlaw.

7. Murray, aged 37. Taken on the 1950 Scottish Himalayan Expedition.

8. Murray at the entrance to the Githri Gorge on the 1950 Scottish Himalayan Expedition. One of many fine shots taken by Douglas Scott who later became a professional photographer.

9. Camp at the base of the Panch Chuli, 1950 Scottish Himalayan Expedition.

10. 1950 Scottish Himalayan Expedition. Centre row from left to right: Scott, Murray, MacKinnon. The six porters are the Dotials who stayed with them throughout the four and a half months of the expedition.

11. Lochwood on the shores of Loch Goil, which Murray bought in 1947 and lived there for the remaining 48 years of his life.

12. Murray (left) at a meeting of the CCS, Battleby House Conference Centre, Perthshire, in 1974. He is talking to Sir John Verney, at that time a Forestry Commissioner and Chairman of the Countryside Commission’s English Committee.

13. Photo taken after presentation of honorary degrees by University of Strathclyde in 1991. Front (l to r): Prof. Ian Macleod, Murray, Sir Graham Hills (Vice-chancellor); back: Peter West, unknown, unknown, and Dougie Donnelly, the TV broadcaster, who was also receiving an award that day.

14. Murray with the adapted slater’s hammer which he used on his pre-war ice climbs.

15. Left to right: Murray, Scott and Weir in their later years.

16. Cover of first edition of Mountaineering in Scotland, published in 1947.

17. Murray’s Highland Landscape, published in 1962, continues to influence country planning reports regarding the delineation and preservation of areas of natural beauty.

18. Murray, aged 80, in his study at Lochwood, reading from his manuscript of Mountaineering in Scotland.

Sources of Illustrations

Black & White:

1–3 Ben Humble, courtesy of Roy Humble

4, 15–23 Douglas Scott, courtesy of Audrey Scott

5 J.E. McEwan

6, 7, 10, 11 SMC Image Archive

13, 14 Imperial War Museum

8, 9 JMCS Archives

12 Courtesy of Anne Amos

24, 25 Tom Weir, with permission of National Library of Scotland, courtesy of Rhona Weir

26 J. Stephens Orr

27–31 Royal Geographical Society

32 Alpine Club

Colour:

1 Robin Lloyd-Jones

2, 4, 11 Michael Cocker

Cover image, 3, 5, 7–10, 15 Douglas Scott, courtesy of Audrey Scott

6, 18 BBC and Triple Echo Films

12 John Foster

13 University of Strathclyde Library, Department of Archives & Special Collections

14 Ken Crocket

16 J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

17 National Trust for Scotland

Sketch Maps:

1–3 Sallie Lloyd-Jones

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the Scottish Arts Council (later to become Creative Scotland) and to The Authors’ Foundation (administered by the Society of Authors) for generous funding which, at various stages, has sustained the research and writing of this book over a period of four years.

I wish to acknowledge a very special debt to Robert Aitken who has been my mentor throughout the production of this biography. His knowledge of all things related to Murray is unrivalled. This he has generously shared with me, supplying me with books, documents, contacts, information and much good advice. The Sunlit Summit could not have been written without his help.

Special thanks are also due to Robin Campbell, The Scottish Mountaineering Club’s archivist, for pointing me towards a wealth of useful material; and to Michael Cocker who made available to me the results of his own research into aspects of Murray’s life, and has allowed me to make extensive use of his annotated Chronology of Murray’s 1935–45 climbs.

Murray was widely respected and admired and this is reflected in the long list of people who were eager to help me celebrate his life and achievements and to offer their assistance. In particular I would like to thank Penny Aitken, Prof. Gavin Arneil, Richard Balharry, Chris Bartle, Dr Donald Bennett, Prof. Ian Boyd, Bill Brooker, Margaret Brooker, Peter Broughan, Alastair Cain, Ken Crocket, Mark Diggins, Elizabeth Dutton, Douglas Elliot, Richard Else, Diana Foreman, John Foster, Dr Abbie Garrington, Ann Gempel, Terry Gifford, Prof. David Guss, A.H. Hendry, David Hewitt, Joy Hodgkiss, Glyn Hughes, Roy Humble, Tomoko Iwata, David Jarman, Bridget Jensen, Dr Michael Jepps, Sir John Lister-Kaye, Jimmy Marshall, John Mayhew, Malcolm McNaught, Rennie McOwan, Findlay McQuarrie, Amy Miller, Prof. Denis Mollison, Graham Moss, Charles Orr, Malcolm Payne, Jim Perrin, Tom Prentice, Dr Martin Price, John Randall, Roger Robb, Jean Rose, Marjory Roy, Des Rubens, Audrey Scott, Gordon Smith, Roger Smith, Hannah Stirling, David Stone, Suilvan Strachan, Greg Strange, Maud Tiso, Russell Turner, Dr Frances Walker, Dr Adam Watson, Rhona Weir, Felicity Windmill, Susan Wotton, Alan Zenthon, Ted Zenthon.

In my research the following organisations were especially helpful: The Alpine Club, Buckfast Abbey Archives, The Glasgow Academy, Imperial War Museum, Island Book Trust, Junior Mountaineering Club of Scotland, John Muir Trust, the Meteorological Office, Mitchell Library, The National Archives, National Library of Scotland, the National Trust for Scotland, Random House Group Archive & Library, Royal Scottish Geographical Society, Scottish Mountaineering Club, Scottish Natural Heritage, University of Strathclyde Archives, Triple Echo Films. My thanks go to the officers and staff of these organisations.

All sources of quotations or special insights have been acknowledged in the notes for each chapter. The sources of the photographs are also acknowledged. My thanks to all concerned for permission to use their work. My thanks, too, to the authors listed in the Bibliography. Not all of them are mentioned in the text, but they influenced my thinking nonetheless.

I am most grateful for the helpful comments made on the draft text by Robert Aitken, Michael Cocker, Andrew Muir, Jim and Olive Muir, Deborah Nelken, and members of the Helensburgh Writers’ Workshop.

The support and encouragement of my family has been important to me during this project. This includes hours of secretarial work by my grand-daughter, Chloe da Costa, research advice from my cousin Angharad Williams, help in solving various computer problems from my niece, Julia Rardin and her son Stephen, and proof-reading and map-drawing by my wife Sallie. To the latter also goes my gratitude for her patience and understanding.

Finally, I would like to thank Robert Macfarlane for his support and for writing such an insightful Foreword to this book; and Robert Davidson, my editor at Sandstone Press, for his cheerful encouragement throughout the project.

Foreword by ROBERT MACFARLANE

The term ‘essay’ (essai), so familiar to us now, was first coined by Michel de Montaigne in 1580 to mean a short prose discussion of a particular subject. Montaigne made his noun out of the verb essayer, which in Renaissance France connoted variously apprendre par experience (to learn from experience) and éprouver (to test or undergo). Implicit in the essay form at its birth, therefore, was a sense of exploration. To ‘essay’ was to try but also to be tried; it involved discovery, but without clear promise of outcome.

W.H. Murray was in life, as on the page, an essayist. Mountaineer, writer, explorer, philosopher, conservationist; hob-nailed aesthete, bank-clerk mystic, secular monk, intellectual knight-errant: he was all of these things, and he was them all adventurously, for the key criterion of adventure was, in his definition, ‘uncertainty of result’. He climbed as he wrote as he meditated as he lived: exhilarated by the endeavour and unsure of the conclusion. ‘Que scay-je?’ was Montaigne’s motto (‘What do I know?’) and it might also have been Murray’s, for like Montaigne he understood that to establish the extent of one’s knowledge is necessarily also to establish the extent of one’s ignorance. Almost all of Murray’s writing – not just his best-known essays – glimmer with ‘the evidence of things not seen’, and are devoted to those kinds of experience that can only be glimpsed or intuited, rather than seized and simply scrutinised. Into the heart of mountain literature, Murray smuggled the spirit.

His greatest essays are prose canticles in terms of pattern and beauty; they ring with fierce joy and sharp wit; and they are also (quietly, unobtrusively) attempts to express the ineffable. Several of their scenes are blazed onto my memory, and have come to influence my own mountain days: swimming in the sea-lochs of Skye, bone-tired but mind-blown; or a winter dusk on high ground, with ‘the wide silent snow-fields crimsoned by the rioting sky, and … the frozen hills under the slow moon’. Yes, Murray knew how to hear what he once called ‘the world’s song’, and he knew how to catch something of that song in language also. Deep in an essay on Glencoe, he talks of those uncommon places where ‘the natural movement of the heart’ is ‘upwards’. His essays are just such places – they leave you shifted, lifted.

There need never be another account of Murray’s life. We have his posthumously published autobiography, and now – in the year of the centenary of Murray’s birth – Robin Lloyd-Jones’s subtle and wonderful biography, The Sunlit Summit. Taken together, these two books tell us all that needs to be known about Murray. Robin has filled in some of the many ellipses of the autobiography, but without ever compromising Murray’s keen instincts for discretion and dignity. He has chosen not to write a cradle-to-grave biography, but instead to focus on those periods when Murray’s ‘life was lived at great intensity’. The narrative structure that results from this decision is intricate in its form and skilful in its moves: with cut-aways from Italian prison-camp to Lochaber ridge, and flash-forwards from the Alps to the Himalayas. We gain oversight of Murray’s long and varied career, and we gain insight to the episodes that shaped him most.

The first of these was his discovery of the hills, which came surprisingly late in his life: Murray grew up in Glasgow as a ‘confirmed pavement dweller’, until in 1935, aged 22, he climbed his first Scottish mountain – the Cobbler in Arrochar – kicking steps in the snow, and slipping upwards in a pair of unsuitable shoes. The experience struck him with the power of a conversion: ‘From that day I became a mountaineer.’ In the five years that followed, Murray was a climbing tiger, pioneering new routes, forcing established classics under desperate conditions, and – in Robin’s phrase – ‘giving back to Scottish mountaineering the impetus which had been lost in the trauma of the Great War’.

Then came the World War II: Murray served in the North African desert during the months of Rommel’s dominance, saw fierce fighting, and escaped death so repeatedly that it came to him to resemble fate rather than chance. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Tobruk, and confined to a series of camps in Italy, Czechoslovakia and Germany, where he suffered severe and prolonged physical deprivation. While for most POWs, incarceration was a closing-down of life, Murray was opened up. He ‘lived inside his mind amongst the mountains he loved’, as Robin finely puts it, and somehow wrote much of what would be published as Mountaineering in Scotland (stuffing the manuscript down the front of his battledress tunic when in transit between camps, and patiently reconstructing it after the first draft was confiscated and destroyed by the Gestapo).

In the camp at Mahrisch Trubau came Murray’s second conversion, when the charismatic younger officer Herbert Buck chose him as his disciple in ‘the Mystic Way’ and inducted him into Perennial Philosophy. Robin is especially good on this encounter, sorting rumour from fact, and demonstrating the consequences of Buck’s teaching for Murray’s later life, including his conservation politics. In 1961 Murray was commissioned by the National Trust for Scotland to produce a report on the Highland landscape, identifying and describing those regions which were of supreme value. With bracing boldness, he elected ‘beauty’ as his chief principle of evaluation, defining it as ‘the perfect expression of that ideal form to which everything that is perfect of its kind approaches’ – hardly the kind of language that would survive the crushing-machine of contemporary planning policy. Murray worked out his definition in part from Plato, and in part from Buck, Huxley and Perennialism. The result was his landmark book Highland Landscape (1962), the influence of which has been pervasive if not dramatic, and which advances Murray’s deeply held conviction that wild places are good places, and that we must preserve them as aspects of what Wallace Stegner once beautifully called ‘the geography of hope’.

At the centre of Murray’s achievement, and therefore rightly at the centre of The Sunlit Summit, is Mountaineering in Scotland: a book ‘written from the heart of the holocaust’, in Murray’s unforgettable phrase. The title of his most famous book has long imprisoned it. Who but a Scottish mountaineer, one wonders, would wish to read a book called Mountaineering in Scotland? The answer, of course, is almost anyone who picks it up. I have long wanted to see Murray understood and valued beyond the borders of ‘mountain-writing’, and the contexts provided here by Robin make that newly possible.

To my mind, Murray should be seen as an outlier of the Scottish Renaissance of the 1930s, and especially as familial with two other great Highland writers, Nan Shepherd (The Grampian Quartet) and Neil Gunn (Highland River, Silver Darlings, The Atom of Delight). Murray shared with both writers an engagement with mysticism (predominantly Zen Buddhism for Gunn and Shepherd; Perennialism in Murray’s case), and with the transcendent experience enabled by certain kinds of landscape, particularly Scottish. The work of all three writers contains crucial moments, set in wild country, in which the consciousness of the subject is expanded to the point of dissolution, and the individual is – as Murray puts it – ‘self-surrendered to the infinite’. If this is a kind of grace, it is Pelagian in nature: and searched-for and ‘self-surrendered’ to, rather than chance-bestowed as in Augustine. Thus Nan Shepherd ‘melting’ into the granite of the Cairngorms – and thus Murray, walking alone and at night, feeling ‘something of the limitation of personality fall away as desires were stilled; and as I died to self and became more absorbed in the hills and sky, the more their beauty entered into me, until they seemed one with me and I with them’. At moments as these, Murray’s language wavers on the brink of production and failure. Words are the only viable medium of record, and yet what is being recorded by definition exceeds language. This has long been the generative paradox of mystical literature, and for Murray – as for St John of the Cross, or Thomas Merton – it is the best way to resist an impoverishing divide between subject and object.

Not all of Murray’s readers have warmed to these aspects of his work and thought: ‘Bill saw an angel in every pitch,’ remarked his climbing companion William Mackenzie (though, like Robin, I take this as an expression of fond bafflement, rather than a jab at ersatz mysticism). Certainly it is easy, when writing of intense spiritual experience, to lapse into a sonorous vagueness. Murray never does, and one reason is that he ballasts his visions with precise empirical detail: thus the ‘fat blue spark where a boot-nail struck bare rock’ as he descends Crowberry Ridge on Buachaille Etive Mor at night, or the plate-like white ice that cracks and shivers off beneath his feet as he struggles his way up Tower Ridge on Ben Nevis.

Murray’s other salvation is his humour. He is a very funny writer, alert to the semi-epic, semi-silly aspects of mountaineering. I often hear hints of P.G. Wodehouse and Pooter in his prose, particularly in the mock-heroic portrayal of his friends Mackenzie, Ben Humble and Archie MacAlpine (the last of whom, as a pyromaniac stoker of bothy fires, ‘had the genius of Satan himself’). At times, reading Murray, the Highlands can feel like a high-altitude, high-risk Blandings – but with the cocktail of choice being ‘Mummery’s Blood’ (three oxo cubes and two gill bottles of rum mixed in a pint of boiling water on a primus stove) instead of Bertie Wooster’s beloved boozy battering-ram, ‘The Green Swizzle’ (rum, crème de menthe, lime, mint, ice, mixed in a highball on a tortoiseshell bar).

The man who emerges in this biography, then, is rich in contrast if not in contradiction: a comic mystic, a modest hero, a lover of the particular but a devotee of universalism, a fierce cleaver to principle but a believer in transcendence. Robin’s own formidable range of learning (‘From Coleridge to Changabang’ reads the title of one chapter, and it might stand for the reach of the whole) allows him to relate the many sides of his subject: he is made vivid in his complexities, lucid in his achievements, and we understand him to be – as Robin puts it – ‘not the second John Muir, [but] the first Bill Murray’.

The last lines of Murray’s autobiography take the form of a retrospect that is also a prospect. He imagines himself in some high place, with life stretching away from him in the form of terrain traversed and loved: ‘Looking back over a wide landscape, cloud shadows racing over the mountains, sun, wind. I know that I have known beauty.’ It is a rare and moving declaration of certainty from a man who was so invested in the importance of not-knowing, and in the enlightenments of ignorance. Beauty was his final conviction: the point to which, over the course of his remarkable life, he had essayed.

Robert Macfarlane, February 2013

INTRODUCTION

To begin with the basic facts of Bill Murray’s life: William Hutchison Murray was born on 18th March 1913 in Liverpool. At the age of two he was taken by his mother to live in Glasgow where he grew up, attending a private school before becoming a trainee banker. He began climbing in 1935. He and a group of friends in the Junior Mountaineering Club of Scotland were soon one of the top ranking climbing teams in Scotland, particularly when it came to winter snow and ice climbing. They gave back to Scottish mountaineering the impetus which had been lost in the trauma of the Great War. His book Mountaineering in Scotland, published in 1947, inspired a similar regeneration following World War II. It remains one of the great classics of mountain literature.

At the outbreak of the war he was commissioned into the Highland Light Infantry. Only a few months later he was in action in the Western Desert in a last ditch defence to slow the advance of Rommel’s tanks. He was captured and spent the next three years as a prisoner-of-war, first in Italy, then in Czechoslovakia and Germany. It was during this time that he wrote the major part of Mountaineering in Scotland. He also used this time to study the Perennial Philosophy – based on the transcendental and mystical elements of the world’s major religions – which was to guide him for the rest of his life.

After the war, Bill Murray considered entering a monastery, but finally chose to make a living as a writer. From his pen came over 20 books, embracing mountaineering, travel and exploration, conservation, history and topography, and four novels. He wrote the first serious full-length biography of Rob Roy MacGregor to appear in a hundred years, which was a landmark in the study of the man. His guidebooks to the Highlands and Islands, as well as displaying an impressive breadth of research, are amongst the most beautifully written of their kind.

In the post-war years Murray returned to climbing and, between 1950 and 1953, took part in several Himalayan explorations. He was deputy-leader of the reconnaissance expedition which established the viability of the route by which the first ascent of Everest was made. From the 1960s onwards he was heavily involved in campaigns to conserve the Scottish countryside. His book, Highland Landscape, commissioned by the National Trust for Scotland, identified areas of outstanding beauty that should be protected. It proved to be extremely influential. The fact that most of these areas remain relatively unspoiled today owes much to his guidance and to his tireless work on a wide range of committees, often as president or chairman. He was awarded an OBE in 1966. Amongst his other awards were the Mungo Park Medal of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and Honorary Doctorates from the universities of Strathclyde and Stirling. W.H. Murray died at the age of 83 on 19th March 1996.

To reach the top and be highly respected in one’s chosen field of endeavour is something achieved by only a few; to have done this in three different spheres of activity – as a mountaineer, as a writer and as a conservationist is truly remarkable. Moreover, within these different spheres he was amazingly versatile. These days, most people become experts by specialising, but Murray was an all-round mountaineer, climbing at a high standard both on summer rock and winter ice, before moving on to Himalayan mountaineering and the exploration of wild and uncharted ranges. As a writer he mastered several forms, producing both fiction and non-fiction. His conservation work encompassed a huge range of concerns and organisations to which he gave unstintingly of his time and energy, mostly for no financial reward.

The vast amount of research he did for his books, in the field and in libraries, covering history, geology, architecture, natural history and environmental topics, combined with his conservation experience, made him a leading authority on matters related to the Scottish Highlands and Islands. He was a man whose advice, opinion and support were sought by many.

A proper understanding of Murray’s life and work requires that we appreciate four things about him: Firstly, his driving force was his quest to achieve inner purification that would lead him to oneness with Truth and Beauty.

Secondly, from this same quest stemmed his striving after denial of self which translated into a life of service to others. This is well illustrated by the various posts he held: Commissioner for the Countryside Commission for Scotland (1968–1980); President of The Scottish Mountaineering Club (1962–1964) and of the Ramblers Association Scotland (1966–82); Chairman of Scottish Countryside Activities Council (1967–82); Vice-president of The Alpine Club (1971–72); President of the Mountaineering Council of Scotland (1972–75).

Thirdly, was his lifelong love of mountains and of exploration. He never spoke about ‘conquering’ a mountain. For him, it was not about ego, but more about mountains helping him to conquer self. The fourth point we need to appreciate is that he was a quiet, modest and extremely private man who sought neither fame nor fortune, and abhorred boasting and any form of self-promotion or publicity-seeking. The consequence of this has been that he has not received the recognition he deserves. Amongst mountaineers, connoisseurs of mountain literature and professional Scottish conservationists, he is remembered and honoured, but to the general public and outside Scotland he is largely unknown. Redressing this situation has been one strand in my desire to write a biography of W.H. Murray.

Although several excellent articles and obituaries about Murray have drawn together his diverse achievements, only a full length account of his life can fully do him justice. This will be the first time that all of his 20-plus books1 have been discussed under one cover. With the perspective of time passed and in the context of the present day, there are new things to say; and the time is right for another look at many of his misgivings about the destruction of the natural environment and the loss of wilderness areas.

In the mid 1960s, I read Mountaineering in Scotland for the first time and was entranced by it. Although I have written other books, this will be my first biography because no other person has filled me with such a strong desire to write about them. I feel that I have at least a few things in common with Bill Murray – as a lover of mountains and of the wild places, as a fellow writer, both of wilderness topics and of fiction, and as someone who, as did he, daily meditates. I am of an age to know what climbing was like in the 1950s. I started climbing in nailed boots (who these days knows what tricounis are?) and with hemp ropes and appreciate Murray’s achievement in pioneering the routes he did with such equipment.

Murray’s quasi-autobiography, The Evidence of Things Not Seen was published posthumously in 2002. Eleven years might not seem a long enough gap for another book about him, but it was the last chance to talk to people who remembered him. Even so, with regard to a number of key people, I left it too late. However 2013, the hundredth anniversary of Murray’s birth, seems a fitting time to bring out a book that celebrates the life of this remarkable man.

In writing The Sunlit Summit I have been aware that there is probably not enough mountaineering detail in it for the mountaineers, nor a deep enough literary discussion for the admirers of his books, and those who move in conservation circles might find it falls short of giving a blow-by-blow account of the many campaigns in which Murray was involved. At the same time, to go into too much detail on any of these aspects would not best serve the majority of readers. I have tried to overcome this by putting additional detail in the appendices and in footnotes. This approach has resulted in a large number of appendices. We decided to put the bulk of these online. Appendix 5, at the end of this book, gives further details about this. The two chapters about his winter ascents of Observatory Ridge and Tower Ridge on Ben Nevis will, I hope, give a flavour of the kind of Scottish routes Murray and his friends were tackling in the 1930s. Likewise I have given two whole chapters to his Scottish Himalayan Expedition in order to convey something of the feel of a lengthy expedition of that kind and its aftermath.

Earlier in this Introduction I indicated that the guiding light in Murray’s life was his mystical philosophy. Some people are uncomfortable with this aspect of his life and they skip the passages in his books that deal with these matters. I would urge any such readers of this biography not to by-pass the two chapters which discuss Murray’s philosophy, for without an understanding of it there can be no real understanding of the man.

This biography does not follow Murray’s life year by year, rather it focuses on those periods when life was lived at great intensity, on key moments and turning points, and on the ruling preoccupations in his life. The last six chapters then attempt an overview and evaluation of Murray as a mountaineer, writer and conservationist, and of his life as a whole.

We learn a great deal about Murray from his own books and articles. In reading them closely and as a complete body of work, certain anomalies and contradictions are noticeable. To my mind, these are not of any great significance. Our lives are seldom conducted on logical and rational lines and memory is less like a filing clerk and much more like an editor trying to make sense of things, to fill in gaps, act as censor and to arrange and re-arrange the material into stories.

About one third of The Sunlit Summit is spent discussing Murray’s books and Murray as a writer. To devote a substantial proportion of the book to this seems appropriate since it was as a writer that Murray elected to make a living; it is through his own writing that we learn most of what we know about him; it was his ability to harness the power of the written word that made him such a persuasive and effective advocate of his chosen causes; and it is his books which are the most tangible reminders of him today. In giving less space to his conservation work I do not mean to underrate the impact he has made in this field, nor the importance of the issues involved. Indeed, with the passage of time, and with environmental problems becoming more and more pressing, this aspect of his work becomes increasingly significant. It may well be that, in years to come, this is what he will be remembered for above all else.

I think it only right that I should say that Murray’s widow, Anne, did not want a biography written about her husband. He was such a private man, she said, and he would have hated the idea. The consequence of this has been that I have not had access to material which undoubtedly would have made this a better informed account than it is. On the other hand, I may have been too late anyway. Several reports reached me of Murray, not long before his death, being spotted burning letters and diaries on a bonfire in his garden – most probably the act of a man protecting his privacy.

I admire Mrs Murray’s loyalty in sticking to what she regards as her husband’s wishes, but once a person enters the public domain they have forfeited their right to at least some of their privacy. Murray himself must have realised that one cannot expect to write over 20 books, some of them influential books, without his readers wanting to know more about the man who wrote them and to discuss what he said. My intention is not to intrude on his privacy except in so far as it illuminates and adds to our understanding of those areas in which he himself chose to enter the public domain.

Although Murray was married for 36 years, he wrote a total of two and a half pages about his wife and his marriage. In doing this, he was following Anne’s wishes. Undoubtedly, his marriage was important to him, but I have not wanted to trespass on private territory and have written only the same amount as Murray did himself on this aspect of his life.

It has been my privilege and pleasure to get to know Bill Murray better than I did before I started writing this book; and my privilege and pleasure, too, to meet so many interesting people along the way. I repeat my thanks here to all those named in the Acknowledgements.

NOTES

1. The exact total of Murray’s books depends on whether, as well as his main works, one is counting (i) books of photographs by others, which have a text by Murray which is only a small proportion of the whole book; (ii) short works written, not for mainstream publishers, but for organisations such as the Junior Mountaineering Club of Scotland, or the National Trust for Scotland; (iii) his quasi-autobiography which was unfinished at the time of his death and was then completed by his wife and published posthumously. Counting all categories, Murray had 25 books published. Appendix 2 shows a complete list of all Murray’s published work, including his many articles, book reviews, and Forewords and chapters in other people’s books.

CHAPTER ONE

THE LONGEST AND HARDEST CLIMB

THE LONGEST AND HARDEST CLIMB1

In February 1938, the same month that Hitler took direct control of the German military, and Walt Disney’s ground-breaking Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was first screened, three young men from Glasgow were mere dots on the vastness of Ben Nevis. Bill Murray, Archie MacAlpine and Bill Mackenzie, were attempting what would be only the second winter ascent of Observatory Ridge. Beset by unexpectedly poor conditions, they had been ascending and traversing unstable snow for more than nine hours. Night had fallen and they were only just beyond the half-way point. A single mistake by any one of them might mean disaster for all. They were tiring and the unremitting danger was ‘not easy to bear with indifference’. Mackenzie was in the lead, cutting steps in the ice:

‘Until my days are ended I shall never forget that situation,’ Murray recalled. ‘Crouching below the pitch amidst showers of ice-chips, I fed out the frozen rope while Mackenzie hewed mightily at the ice above, his torch weirdly bobbing up and down in the dark and the ice brilliantly sparkling under its beam. Looking down, I could see just a short curve of grey snow plunging into the darkness, then nothing until the twinkling lights of the Spean valley, four thousand feet below.’

The plan to make a winter ascent of this classic ridge had been hatched about a month before. As was their habit, Murray, MacAlpine and Mackenzie gathered on Thursday evening in MacAlpine’s Glasgow home to plan their weekend climbing. At one such meeting in January 1938, amongst tankards of beer and maps spread out on the sitting-room floor, they discussed the ridges on Ben Nevis which, they reckoned, should be in perfect condition. Despite heavy falls of powder-snow, the strong and continuous winds would have swept them clean, exposing the older, harder, more secure snow and ice beneath. Then Mackenzie remembered that Observatory Ridge had not been climbed in genuine winter conditions since Raeburn’s first winter ascent eighteen years earlier. It was a long climb – all of two thousand feet and not one, as Murray puts it, ‘on which one could wander with an old umbrella.’

Soon after resolving to attempt the ridge in winter conditions, Murray sprained an ankle – not, he admits, as the result of some mountain escapade, but from slipping on the floor of a friend’s house.2 With growing impatience he rested his ankle while the days of perfect conditions slipped by and his friends regaled him with accounts of the wonderful climbing he was missing. Finally, ‘sprain or no sprain, my stick went out of the window and I to Nevis with MacAlpine and Mackenzie.’ And so, on Saturday 19th February, after finishing at work, they drove to Fort William. Their objective was The Scottish Mountaineering Club’s Charles Inglis Clark Memorial Hut, high in the Allt a’ Mhuillin glen on the fringe of Coire Leis, at the foot of the Nevis cliffs. As Mackenzie admitted, ‘They lingered at the fleshpots’,3 not setting out for the hut until 8.30 pm. They lost the rough track and stumbled about in the freezing dark with loaded rucksacks. Not until midnight did they gain its warm, welcoming fug and the chance to brew up steaming mugs of rum punch.

Although referring to another occasion, Murray’s report for The Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal of a meet held at the hut gives something of the flavour of those late night arrivals:

‘Under the most adverse conditions of rain, mist and utter darkness, Murray succeeded in forcing a new route from the Distillery [the whisky distillery outside Fort William] to the hut. Although no beckoning light shone from its windows the snores of its occupant provided a sure and sufficient guide for the last few feet.’4

The hut’s eight bunks, Murray says, were the best sprung and most comfortable on which he had ever slept. No doubt the long walk up to the hut or a hard day on Nevis had something to do with their perceived excellence. Murray described the hut as a school of further education. He didn’t elaborate on this, but it is clear that this was a place to meet not only the top Scottish and English climbers of the day, but also a variety of interesting and eccentric characters and to learn from them. Murray captures the cosiness and warmth of that hut when he writes: ‘I scrambled into my bunk. I lay back gratefully, watched the stove glow red through the darkness and listened to the wind thunder on the walls and roof.’5 Of the joys of the glowing stove, he adds: ‘Especially was this true if Archie MacAlpine was present. As fire stoker, he had the genius of Satan himself. Perhaps inspired by the latter after a heady brew, he once stoked the stove to an unprecedented redness, forgetting that he had put his blankets into the oven to warm.’6

Murray, Mackenzie and MacAlpine awoke that February morning to a clear, crisp, cloudless day. ‘Straight from the doorway stretched the two miles of precipice, crowned with flowing snow-cornices, which blazed in the slanting sun-rays. From our feet the snowfields swept in a frozen sea to the cliffs, beating like surf against the base of ridge and buttress, leaping in spouts up the gullies.’ From the hut it looked as if their predictions had been correct and that the ridges had been cleared by the wind. In front of them Observatory Ridge gradually tapered until its final thousand feet formed a delicate edge. They set out, their eyes feasting on the glinting mountainscape, the feathery powder ‘squealing beneath our boots like harvest mice’.

As they approached Observatory Ridge via the base of Zero Gully, the latter seemed to them to be impregnable, so full was it with green overhanging ice. The lower flanks of Observatory Ridge immediately posed problems with loose, sugary snow, piled on ledges and slabs, threatening to slide off into space. They roped up and Mackenzie took the lead. Half an hour of searching this way and that finally yielded a possible way up. Even so, the holds on this almost vertical rib were ‘distressingly far apart’. They overcame this first challenge only to find that, above it, there was more of the same. They had expected things to improve higher up where the wind should have scoured the ridge of powder-snow. Instead, they became worse. At one point, Murray was crossing a steep slab when the snow gave way beneath his feet. He slithered towards the edge and the huge drop below, just managing to stop his slide by latching onto two small finger-holds – an incident which played upon their minds, adding to the strain. In one ‘loathsome and slabby gutter’ the snow, which was providing the only available footing, flaked away before MacAlpine, who was last on the rope, had a chance to tackle it. Murray, directly above him, prepared to bring him up on the rope while standing on a single small foothold and with his only belay a tiny knob. It seemed inevitable that MacAlpine and the rock would part company at some point on his way up the treacherous gutter and far from certain whether Murray would be able to take the strain of it without being pulled off himself.

‘When assured that all was ready and that my belay “would hold the Queen Mary,” he calmly stubbed out his cigarette, carefully smoothed the corners of his moustache, tilted his balaclava, then with stylish glide came up that gutter like a Persian cat to a milk saucer.’

Once past the gutter they made better progress, steadily surmounting a succession of slabs, ledges, ribs and faces. When the angle of the ridge temporarily eased off they stopped for lunch on a wide stance. Below their feet the roof of the Nevis hut was a tiny red speck. They were now about mid-way through the climb. The ridge steepened again into a broad tower 70 feet high. Mackenzie disappeared round an awkward corner. The rope inched out painfully slowly. Apart from the occasional soft scuffling, ‘all was silent save for the whisper of falling snow.’ It took the three of them over an hour to get past those 70 feet. Now the ridge narrowed with huge cliffs on either side. Here, on the upper part of the mountain, they had expected it to be clearer, easier going. To their consternation it was smothered in huge volumes of unstable powder-snow. The sun was sinking low in the sky. They knew they were in trouble and that they had a long hard fight ahead of them. Mackenzie made the decision to leave the ridge and traverse along its western face.

Two hours later, the shelf along which they were slowly edging took them to a knife-sharp saddle and a subsidiary ridge which would lead them back to the main ridge. ‘Mackenzie literally swam up these hundred feet, using the dog-stroke to cleave a passage up the massed powder.’ As the sun was setting, after seven hours of climbing they found themselves once more on Observatory Ridge, but still with a long way to go. Despite their predicament, they could not but be impressed by the glorious sunset with the peaks aflame.

To give Mackenzie a rest, Murray took over the lead. Immediately he found the narrow upper section of the ridge swamped with powder held together only by ‘an egg-shell crust’. It was unclimbable. The SMC’s Ben Nevis guidebook clearly stated that it was not possible to escape from the ridge into either of its flanking gullies. ‘Unless we could reconcile ourselves to remaining where we were permanently the guide-book had to be proved wrong.’

In the gathering gloom they forced their way into Zero Gully. The same gully which lower down they had deemed impregnable now looked the better choice.7 At this point in his narrative Murray pays tribute to Mackenzie and MacAlpine. With darkness falling, temperatures plummeting, fatigue setting in and their chances of survival rapidly diminishing, their cheerfulness and optimism boosted his own morale. In such circumstances, he says, ‘it is the strength of the team, not of the individual, that carries the day’.

At last, in Zero Gully, with stars burning bright in the clear night sky, they found hard ice – the kind of ice in which they could cut firm, safe steps. Their hopes rose only to be dashed when they encountered yet more soft, unstable snow which continued all the way to the summit. They were tired and it was numbingly cold. The temptation was to risk it and hope that this loose layer would stay in place when they stepped on it and not avalanche into space. Experience told them, though, that they must excavate down to the hard ice beneath and then cut steps in that. Painstakingly, laboriously, they worked their way upwards, taking turns to lead. After two hours they reached the first ice-wall. Mackenzie dislodged a huge plate of snow-crust which fell onto MacAlpine’s head, shattering into a thousand pieces.8

Another two hours went by. Two hours of hard labour or of waiting in the cold and dark, standing on small holds. With both their strength and their torch batteries fading, they overcame a second and then a third ice-wall. ‘Up and up we went, digging, hitting, carving, scraping.’ Suddenly, close to midnight, Zero Gully opened out and they were on the summit plateau. Mackenzie’s lead that day was, says Murray, the greatest he would ever see on any mountain.

They had been in unrelenting conditions of danger for 14 hours.9 In Murray’s opinion it was the longest and hardest climb in relation to sheer strain that he was ever likely to do. ‘We had learnt that when one stands on the summit after such a climb it is not the mountain that is conquered – we have conquered self and the mountain has helped us.’ This second winter ascent of Observatory Ridge provided what Murray regarded as mountaineering at its best – there had been both adventure and beauty, ‘the criterion of the one being uncertainty of result, and of the other, always inner purification’.

NOTES

1. The account in this chapter is based on Chapter XI, ‘Observatory Ridge in Winter’ in Mountaineering in Scotland and all quotes come from here unless otherwise stated.

2. Michael Cocker in his Chronology of Murray’s pre-war climbs has this to say about Murray’s mention of an injured ankle: ‘This is a curious statement because both Murray’s and MacAlpine’s applications [to join the SMC] show that they attempted Crowberry Gully together one of the two previous weekends’ And Cocker goes on to point out that when writing about January 1939 (Undiscovered Scotland, page 112) Murray says, ‘It even began to seem likely that we would miss a weekends climbing for the first time in eighteen months,’ which suggests he didn’t miss one in February 1938. Cocker concludes that Murray either made a mistake with the timing of these events or moved his injury on a couple of weeks for literary effect.

3. Mackenzie wrote his own account of the climb (SMCJ, 1938). It is interesting to compare it with Murray’s account. There is no disagreement regarding the facts, but the styles are very different. Mackenzie’s is a functional report, brief and to the point, understating the difficulties. Murray’s is a literary essay which is expansive, reflective and dramatised, with a wider readership in mind than Mackenzie had.

4. Later, another of Murray’s climbing companions, Dr J.H.B. Bell, who was then editor of The Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal, parodied this passage, in a footnote to an article by Murray, who had recently joined the army and was in the Middle East. The footnote gave a mock serious account of Murray forcing a route up the Sphinx outside Cairo.

5. Undiscovered Scotland, page 166.

6. The Evidence of Things Not Seen, page 37.

7. Zero Gully was not climbed in its entirety until 1957 – 19 years later – when Tom Patey, Hamish MacInnes and Graeme Nicol made the first ascent.

8. There is further mention of this incident in Chapter Seven.

9. The extent to which a winter route can vary in difficulty according to the conditions is demonstrated by the fact that, one year later, Murray repeated the same climb in six hours.

CHAPTER TWO

THE COMPANION GUIDE TO BILL MURRAY

Testing climbs like Observatory Ridge under severe winter conditions strip away the veneer and reveal a personality’s true core. We learn a great deal about Murray from his reactions and behaviour on this climb and from the way he wrote about it and other climbs. For a more rounded picture of him, though, we need to see him in other situations and through other eyes.

Bill Murray was tall and lean, with a sharp beaky nose, thick dark hair and grey-blue eyes – eyes which a friend described as ‘mountaineer’s eyes that seemed to see to the far horizon’. Hamish MacInnes likened him to ‘a frugal, contemplative eagle’.1 Obviously he changed in appearance over the course of his 83 years – his hair thinned, he took to wearing spectacles and needed dentures. One person who knew him in later life said: ‘He struck me as an old-fashioned gentleman. He was a tall, lean, spare, rather ascetic-looking man who seemed to me quiet, refined and civilised. He was reserved but certainly didn’t have any of the airs and graces that one might expect given his fame and wasn’t at all intimidating.’2 Murray spoke in a polite, slightly refined way, which must have owed something at least to his mother, whose genteel accent made ‘Bill’ sound like ‘Beel’. To say that he was slow of speech would be an understatement. It was as if he was weighing and measuring in his mind every word and sentence for content, accuracy and style as judiciously as he would were he writing rather than speaking. There were long pauses while he searched for exactly the right word. ‘Sometimes it took a long time,’ said a friend, ‘but it was always worth the wait.’ Others found it a bit disconcerting.

When Murray was 37, Tom Weir wrote an unpublished profile of him. He opens with this description of Murray:

‘Study the portrait of Bill Murray. There is an air of preoccupation in the eyes. It is the face of a scholar rather than a man of action. But note the determined cast of the brows, and the leanness which betrays physical fitness. Yet if you were in his company for the first time you would remark nothing save that this tall, rather spare man, is quite self-contained, without being self-effacing. If you talk to him he will let you do most of the talking. You may think he is not listening, but the chances are you would be wrong. Behind that impassive front is the most alert brain it has been my good fortune to meet.’3

We are all the product of our times, influenced to varying extents by the attitudes and values that prevailed in our formative years. Sometimes we become who we are because we rebelled against what we saw as ‘the old order’; and sometimes we absorb these ways of thinking and of seeing the world without even being aware of it. In most cases, we do both and Murray was no exception. When he was growing up between the two world wars the class system was in full swing; the middle classes, for the most part, had servants; and respect for authority was well embedded in most of the British population. In sport there was a clear distinction between amateurs and professionals. In cricket, for instance, there used to be an annual match in England between the Gentleman (the amateurs) and the Players (the working-class professionals). It went without saying that the captain of any county or national team had to be an amateur, that is, an educated, upper and officer class person of suitable social status.4 Although these social distinctions were not quite so pronounced in Scotland as in England they were there nonetheless.

Shows of emotion were regarded as embarrassing and ‘un-British’ and were discouraged. Modesty, self-deprecation and even, to a certain degree, a lack of self-belief were regarded as attractive traits, whereas in today’s ‘because I’m worth it’ and ‘be all you can be’ culture they are regarded as handicaps. People were generally much more ‘buttoned up’ than now. Sexual morality was a great deal sterner and more restrictive. Sex before marriage was a matter of much agonising and disapproval; people talked about ‘living in sin’ and to have a child outside wedlock was a social disaster both for mother and child – and these were the days before the contraceptive pill. Ignorance of matters related to sex was more prevalent than now – many men, for example, did not know that women had periods, or only the vaguest notion about it. Homosexuality was illegal, even between consenting adults, and was punishable with a prison sentence. Anti-semitism still lingered. The term ‘to jew someone,’ meant to cheat them. Teenagers had only just been invented and were found mainly in America; the British Empire was still something people were proud to be part of; and, in cinemas, when the national anthem was played at the end, people stood to attention. Nobody made a connection between smoking and cancer, indeed a lot of people thought the former was good for you; no threat of nuclear war hung over the world; the idea of somebody landing on the moon was just ridiculous fantasy; there was no National Health Service or welfare state and few safety nets of any kind that individuals did not have to pay for themselves. Central heating in houses was only for the rich; people seemed hardened to cold to a much greater extent than now – nearly all public swimming pools were open-air and unheated. Murray and his friends would frequently swim in lakes and rivers, even in autumn, and think nothing of it. Men still adopted a patronising attitude to women, often regarding them as decorative appendages. It was not until 1928, when Murray was 15, that all women over 21 were given the vote. In 1918 the school leaving age was raised from 12 to 14 and in 1930 to 15. In fee paying schools, the classics still dominated the curriculum. Unemployment was at a high level throughout most of the 1920s and 30s. Murray was ten when the General Strike brought Britain to a halt and he was 19 when the hunger marches took place.

Murray had a well-developed sense of service to others and of concern for his fellow beings. ‘Of all the questions ever asked by man,’ he wrote, ‘the most ignorant has been Cain’s: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” That acme of self-love is evil’s real root.’5 This belief showed itself in action in his selfless public life (documented elsewhere in this biography) and in his many acts of personal kindness to individuals. Bob Aitken, while still at school, wrote to Murray asking for his advice about how to become a mountaineer. Murray, at the time, was up to his eyebrows in work, trying to organise a Himalayan expedition. A lesser man would have ignored this letter from an unknown schoolboy. But not Murray. He replied at length, giving a great deal of practical advice, and offered, once he had returned from the Himalayas, to take Bob and a friend for a day on the hills –