Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Berlin Story Verlag GmbH

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

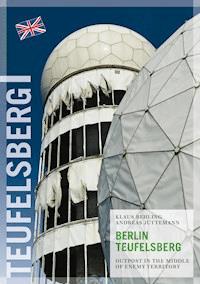

Rising to 115 metres Berlin's Teufelsberg is not only one of Berlin's highest points, but also a place steeped in history. Berlin's university headquarters were to be based here under National Socialism, after the war it became the largest depot for post war rubble and later the winter sports, climbing and wine making centre of the city. A radar station was built on Teufelsberg and the Western allies listened in to the East from the top. The equipment has been abandoned since 1992 and Teufelsberg has succumb to vandalism and decay. No use has been found for the area despite numerous plans and attempts. This "lost place" in the inner city districts of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf has become a place of myths. This book tells the true story. Excerpt: The plans for the athletic development of the mountain had, however, always been public and once again demonstrated: Berliners were never shy about offering a stage even to basically meaningless things. Even the rubble of their destroyed city could be put to good use! But what does a real mountain need? First of all, one should be able to ski there in the winter, and children should be able to ride sleighs. ...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 62

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BERLIN TEUFELSBERG

KLAUS BEHLING

ANDREAS JÜTTEMANN

BERLIN TEUFELSBERG

OUTPOST IN THE MIDDLE OF ENEMY TERRITORY

Klaus Behling/Andreas Jüttemann:

Berlin Teufelsberg – Outpost in the Middle of Enemy Territory

First edition – Berlin: Berlin Story Verlag 2012

ISBN 978-3-86368-717-5

All rights reserved.

© Berlin Story Verlag and the authors

Alles über Berlin GmbH

Unter den Linden 40, 10117 Berlin

www.BerlinStory-Verlag.de, E-Mail: [email protected]

Cover: Norman Bösch

Typesetting: Stephanie Hönicke

Translation: Simon Hodgson, Anja Wiest

WWW.BERLINSTORY-VERLAG.DE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SUBMARINES IN THE GRUNEWALD?

FROM A GRAVE OF RUBBLE TO THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN BERLIN

SNOWMEN, HIKERS AND SOLDIERS

AMERICA‘S BIG EARS

“LIGHTNING” STRIKES THE TEUFELSBERG

HOT JOB IN THE COLD WAR

SECRETS AND RUMOURS

FIGHT FOR THE FUTURE

FROM PRIME LAND TO HIKING PATH?

GALERIE

SOURCES

Books

Articles

TV and Film

Images

Grunewald, with the river Havel and the Grunewald tower in the background, after 1945

SUBMARINES IN THE GRUNEWALD?

The story of the Berlin Teufelsberg begins in the Grunewald, a flat expanse as far as the eye can see.

On November 27, 1937, Adolf Hitler laid the foundation stone here, between Heerstraße and the Teufelssee, for a building intended to stand for the next thousand years: the Berlin Technical University‘s “Faculty of Defence Technology”. The ceremonial act also signified the start of construction work for his megalomaniac plans of a new Reich capital. On June 8, 1942, the “Führer” decides to call it “Germania”; three months earlier he had rambled about a “world capital”. It was to succeed the old Berlin built on Mark Brandenburg sand and become the new symbol of the Nazis‘ “Thousand Year Reich”.

Until then all plans by Nazi chief architect Albert Speer (1905-1981) had been kept secret to the greatest extent because the plans for the East-West Axis, which ran from Wustermark along Heerstraße into the centre of Berlin, required the destruction of numerous public buildings as well as 50,000 apartments. Many of those 150,000 directly affected were Jews whose forced resettlement ended in their physical annihilation.

The building of the new “university city” near the Olympic stadium was supposed to replace these areas. The activity occurring south of Heerstraße therefore did not remain hidden from Berlin‘s population. Rumours flourished. The strangest assumption: a huge subterranean lake was being built to test submarines!

But the people were not entirely wrong in their assumptions, since the construction did involve armament and research related to it. And prestige. The “Berliner Tageblatt” confirmed this on November 28, 1937, when it published Hitler‘s speech at the laying of the foundation stone: “It is my unchangeable will and decision to provide Berlin with those streets, buildings and public places that will for all time appear suitable and worthy of being part of the capital of the German Reich.” Then the dictator gets down to business: “Under this holy conviction I now lay the foundation stone of the Faculty of Defence Technology of the Berlin Technical University as the first construction to be created as part of these plans. It should become a monument of German culture, of German knowledge and of German power.”

The plan was to give a new home to the Technical University‘s “Faculty of Defence Technology”, which had already been founded in 1933. It succeeded the “Military Academy” that had closed in 1918 after the loss of World War I and initially carried the seemingly harmless name of “Faculty of Technology”.

Nonetheless, the faculty‘s purpose became clear, since it already presented “Defence Technology” as the centre of its teaching programme in the winter semester of 1933/34.

True to their ideological standpoints, the Nazis viewed the ostensibly academic “Defence technological” education they offered future generations as the culmination of a national socialist upbringing, which could only end in service at the front. Accordingly, the plans for the Technical University‘s buildings and the “Faculty of Defence Technology”, designed by Hans Malwitz (1891-1987), architect and speaker in the building division of the Reich Treasury, not only mirror the credo of Speer‘s monumental buildings, but also document the siege mentality the Nazi elite was breeding in its offspring.

The complex, enframed by buildings like an insurmountable wall, in no way gives the impression of a free or even democratic education. Arranged with precision, the barrack-style buildings in the courtyard – eight altogether – are dominated by a square, fortress-like building with four corners on one side and a structure shaped like a gate on the other.

The Nazis estimated a sum of 80 million Reichsmarks just for the realisation of the plans. And the “Faculty of Defence Technology” was only one part of the planned university city, the centre of which would lie east of the faculty in the direction of Heerstraße. Among other things, a huge Auditorium Maximum would be created, the transmission capacity of which was to resemble the Athens Parthenon of ancient Greece. A new university hospital would also find its home here, replacing the time-honoured Charité in the city centre to make a space for the monumental insignia of the “Thousand Year Reich”.

Photo of the architectural model of the Faculty of Defence Technology (from the national archives), around 1935

After the laying of the foundation stone, building work was accelerated and the shell of the building with its four towers rose quickly. At the same time, Germany was also concentrating on war preparations. Although turning Berlin into the “World Capital Germania” remained Hitler‘s favourite project, manpower and materials became scarce. In February 1940, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring ordered the discontinuation of the building of those structures not considered important for war.

On April 8, 1940, the designated “Faculty Leader” of the „Faculty of Defence Technology”, General of Artillery Karl Becker (born 1879), committed suicide. He had been in charge of the German Army Weapons Agency since March 1, 1938, and was now held responsible for the shortage in the production of ammunition. The Nazi regime honoured him with a state funeral on April 12, 1940, on the square in front of the Technical University. Still, the “Faculty of Defence Technology”had now lost its master builder.

So the buildings remained skeletons and expected their completion after the “final victory”. The ostentatiously announced „Monument of German Strength” never witnessed a single lecture.

Rudolph Mühlbecher, who had a few months‘ vacation from the front in that year to study at the Technical University, remembers how the troops had continually been lured with the future blessings of the new faculty. The reality, however, presented a different picture: lectures in crowded rooms during the day, nights spent on guard and cleaning duty after the numerous bombings of Berlin.

When allied bombers had already reduced large parts of the city to rubble, Hitler was still dreaming of his “world capital” with monumental constructions. On June 22, 1950, as an inmate of the Spandau prison for war criminals, Albert Speer recalled the speed with which Hitler intended to build it. He wrote in his diary: “During these weeks in 1950, the first section of the planned world capital ‘Germania’ should have been complete. When I agreed to this deadline in 1939, Hitler raved about a world exhibition that would take place in 1950 in the empty rooms.”

In reality, things took a different course. During the early years after the war, numerous deposits for the city‘s debris had exceeded their capacity. The barely destroyed skeleton of the “Faculty of Defence Technology” would provide a stable foundation for a landfill mountain – and the demolished bunker in Volkspark Friedrichshain for the 78-metre-high “Mont Klamott”.