Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Brandon

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

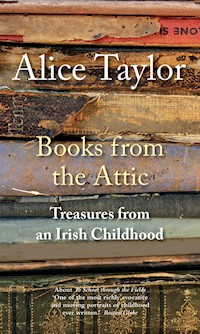

Alice Taylor takes a look back at the well-used schoolbooks she used in her youth in the 1940s and 1950s. Flicking through the pages of the books and recalling poetry and prose she learned at school, Alice reminisces about these texts, how she related to them and how they integrated with her life on the farm and in the village. In her warm, wise way, Alice reflects on poems and stories on topics ranging from birds, trees and nature to fairy tales and legends, and ties them in with her own knowledge and memory of traditional country life. Containing the text of the poems that readers will remember from their own school days, and evocatively illustrated with photographs of the school books and Alice's notes on them, as well as nature, flora, fauna and objects associated with schools of old, this is a reminder of childhood days and a treasure trove of memory.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About Alice Taylor’s other books

To School through the Fields ‘One of the most richly evocative and moving portraits of childhood ever written.’ Boston Globe ‘A delightful evocation of Irishness and of the author’s deep-rooted love of “the very fields of home” … with its rituals and local characters’ Publishers Weekly

Do You Remember? ‘magical … reading the book, I felt a faint ache in my heart … I find myself longing for those days … this book is important social history … remembering our past is important. Alice Taylor has given us a handbook for survival. In fact, it is essential reading’ Irish Independent

For more books by Alice Taylor, see www.obrien.ie

3

Books from the Attic

Treasures from an Irish Childhood

Alice Taylor

Photographs by Emma Byrne

Dedication

In gratitude to Mom, Gabriel and Con, who had the wisdom and foresight to hoard this treasury of old books, which made the writing of this book possible.

6

Contents

8

Chapter 1

A Hoarder’s Haven

Welcome to my attic! A family of old friends lives up here. Over the years they crept silently up the steep, narrow stairs, gently eased open the creaking door and slipped in quietly. They made themselves comfortable and now have earned their right of residence. When my life downstairs was frantic with the demands of business and small children they reached down with welcoming arms and raised me up. Up here in the restful silence they fostered and encouraged my first tentative steps into the world of writing. These comforters were handed on to me by family hoarders who had cherished and loved them for decades. Now they are my protégés and I would like to introduce them to you, and you may be pleasantly surprised to be reunited with some long-forgotten friends, and hopefully make new ones. 10

My mother was a hoarder and kept all our schoolbooks. My husband Gabriel was another hoarder who kept his schoolbooks. My cousin Con, who became part of our family, was an extreme hoarder and brought all his old schoolbooks with him when he came to live in our house. So a deep drift of old schoolbooks was building up and would eventually swirl in my direction.

In the home place, my mother stored all our old schoolbooks up in a dark attic that was christened the ‘black loft’ because in those pre-electricity days only faint rays of light penetrated its dusty depths under the sloping roof of our old farmhouse. Gabriel stored his in a recess under the stairs, which he had cordoned off from our destructive offspring. You entered his mini library via a handmade little door secured with a bolt above child-level access. An adult gaining entry to this literary archive then had to genuflect and go on all-fours to reach the shelves in the furthest corners. Con stored his books under his bed and on shelves all around his bedroom, until the room resembled a kind of beehive of books. When these three much-loved family members climbed the library ladder to the heavenly book archives, I became the custodian of all these old schoolbooks.

My sister Phil sorted out our mother’s collection of a lifetime, brought them from the home place and landed a large box of books on my kitchen table with the firm instructions: ‘You look after these now.’ We went through them with ‘Ohs’ and ‘Ahs’ of remembrance. In the box was 11a miscellaneous collection of moth-eaten, tattered and battered-looking schoolbooks. Amongst them was a book that had belonged to our old neighbour Bill, who had gone to school with my father. It was somehow uncanny that here was a reminder of Bill, who, every night during our childhood all those years ago, came down from his home on the hill behind our house and taught us our lessons. He was a Hans Christian Andersen who loved children and had the patience of Job, so he was the ideal teacher and we loved him dearly. He spent long hours teaching us our lessons; one night he spent over an hour patiently trying to drum the spelling of ‘immediately’ into my heedless head. All the books eventually found their way up into my attic with promises of: Some day, some day! Isn’t life littered with good intentions!

For many years all these old books remained stored away in the attic, gathering dust. Occasionally when I was up there rummaging through miscellaneous abandoned objects looking for something else, I would come across one of them. Planning just a quick peep inside, I was still there half an hour later, steeped in memories. These impromptu sessions transported me back into the world of To School through the Fields.

That first peep into a book sometimes led to a search through others along the shelves, looking for another where a half-remembered poem or some lessons I half-recalled might be hidden. Having found that other book, the nearest chair was sought and a journey back down memory lane 12ensued. This sometimes provided a welcome break in a then busy schedule downstairs and there was deep satisfaction in these stolen moments.

There and then the promise would again be made that one day all these old schoolbooks would be gathered together and sorted out. I owed it to my mother, to Gabriel and to Con, who had all so carefully preserved them and entrusted their future to me. Unfortunately, it never happened. But lodged at the very back of my mind was the thought that one day when I too would climb the golden library ladder all these old books could well finish up in a skip! A terrible thought! But if I, who knew and loved the history of these books did nothing with them, how could I expect someone who had no nostalgic connection with them to do what I had failed to do? But after these episodes it was back on the conveyor belt of a busy life, which flattens us all. But sometimes life has a funny way of working things out in spite of us and as time evolves it comes up with its own solutions. And so it was with this collection of old schoolbooks.

On recent long car journeys, my grand-daughter Ellie, aged seven, and I are back-seat passengers, and these journeys invariably evolve into storytelling sessions. And one day I said to Ellie: ‘I think that I have become your Gobán Saor.’ ‘Nana, what’s a Gobán Saor?’ she inquired.

Now, there are many stories about the Gobán Saor, I told her, but probably the correct one is that he was a very good mason who worked for free or very cheaply, was skilled at building, and always managed to get his due, whatever the 13circumstances. But my favourite story about him is this. And so I told her my version of the Gobán Saor story, in which he is a man who loved storytelling. She loved it.

Long, long ago there was a Gobán Saor who had a large kingdom and three sons. He had to make a big decision. He had to make up his mind to which of his three sons he would leave his kingdom. This was a very big decision. So one day he took the eldest son and some of his courtiers on a long, long journey and when they were all getting weary he asked his son: ‘Son, shorten the road for me.’ The son looked at him in surprise and protested: ‘Father, how can I shorten the road for you? I cannot cut a bit off it.’ So they continued on in silence.

The following day the king took his second son and as they walked along he said to the second son: ‘Son, shorten the road for me.’ And the second son made the same response, so they walked on in silence. When they came home that night the queen knew that the following day it would be the turn of the third and youngest son. This son was kind and wise and would make a good king, and she wanted him to inherit the kingdom. So that night she whispered a secret in his ear.

The next day as the father and son walked along, the father said to his youngest son: ‘Shorten the road for me, son.’ And the son began to tell his father a fascinating story to which the father and all the courtiers listened in awe. The time flew by and they never noticed the long journey and arrived at their destination in no time at all. And so the youngest son inherited the kingdom. 14

When Ellie heard this story she absorbed every last detail and demanded that it be retold many times, precisely as she had first heard it. The Gobán Saor led on to other old stories and she was completely fascinated by the stories, myths and legends that I had learnt in school. A visit back up to the attic was necessary to re-familiarise myself with these stories. Many had totally faded from my memory and rediscovering them was like meeting up with old friends. I decided now was the time to rescue the old books.

I gathered them all together into one long flat box, brought them downstairs and spread them out on the kitchen table. It was an old school reunion. At last all these old friends were back together. Many were tattered and torn from lots of grubby-fingered thumbing and years of dusty storage. Some covers were missing and of other books there was only the cover – but even a cover can sometimes tell a story. One ragged cloth cover was stitched to a book with Bill’s name on it and was dated 1907. On another book was my father’s beautiful copperplate writing. That generation took great pride in the art of handwriting, or ‘having a good hand’ as my grandmother termed it.

Back in those days the books on the curriculum were seldom changed as books cost money and that was a scarce commodity, so schoolbooks were passed down from one family member to another, one generation to another, and indeed often from neighbour to neighbour. So these books had the names of many members of the family and sometimes of old neighbours inscribed in them. When leafing 15through many of them, I felt like saying: ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant’, because these books had indeed taken good care of their contents and served us well.

These were the books that were used in the National Schools of Ireland during the 1940s and 1950s, and probably since independence in the 1920s. Amongst my collection too were copies of books that were used in the early years of the small secondary schools set up around rural Ireland by enterprising young graduates who wished to bring education back to their own place. At that time not every family could afford to send their children to boarding school and in remote rural areas there were no convents and monasteries with nuns and brothers who were then the main educators in cities and towns. Those small rural secondary schools provided second-level education for many of us who would otherwise have gone without. These young educational entrepreneurs could have found jobs in well-established convents or colleges, or emigrated to exciting new places, but chose instead to face an uncertain future and invest their time and money in renting premises to set up these small schools. Sometimes they were following a family tradition – the grandfather of the young man who started our secondary school had, years previously, taught in our old school across the fields. They occasionally provided education for children whose parents were not able to come up with the small fees that they charged. These teachers are the unsung educators and enlighteners of many young minds around rural Ireland. We owe them a debt of gratitude. 16

Then I came across a wonderful book, The Secret Life of Books, by Tom Mole, which made me think about how precious books are. It was another incentive to rescue the old books in the attic. What secrets would they reveal? How would I relate to them now, so many years later? Would they still live or would they have faded from my mind? And so, after long years of wondering quite what to do with these old schoolbooks, a seed was planted and Books from the Attic began to take shape. My mother, Gabriel and Con had entrusted the books to me. They should not be lost; their stories and poems are from another time and another place and are a huge part of our culture. So please find a comfortable chair and put your feet up. It’s time for the Gobán Saor!

Chapter 2

My New Book

My arrival into first class and being presented with a brand new Kincora Reader was a day to remember. It had a gorgeous smell and you got a thrill of excitement just running your fingers up and down the shiny pages. A brand new anything was much appreciated in our world back then!

Our schoolbooks were seldom new. They were ‘hand-me-downs’, going through large families, and, for me, being sixth in the line of succession, mine always had the evidence of much wear and tear before they eventually reached me. This system of handing on books worked because there was never a change of books on the curriculum. So the acquisition of a pristine, untainted copy was a big occasion. Such a thing would only come about when an old copy of a particular book had absolutely fallen 18asunder or gone missing. A rare event! We were cautioned to take good care of our books, and we did as we were told because we were well aware that if a precious book went missing there would be ‘míle murder’. Books cost money, and money was hard-earned. So a brand new book was a rare treat. To me it felt almost as if this special book had a life of its own and could almost teach me by itself! The fact that the first lesson in the new book gave instructions on how it should be treated came as no surprise at all – that this new book was actually talking to me was quite within the realm of possibilities. Things could not get any better than that! Each word was absorbed and all the commands that this new book issued were carried out with absolute delight.

Take Care of Me

I am your new book, and I want you to take good care of me. Keep me clean, please, and cover me with stout brown paper. I do not want to look old and torn before my time.

One little person in the front desk – a little person with curly hair – is saying now:

‘Books can’t talk!’

But this little person is wrong. I can talk, for I shall be telling you stories from now until the end of the year. So no one can blame me for saying a little about myself.

You will find a few hard words here and there in my pages. I am sorry about this but it is not my fault.

By the end of the year, too, you will find that these hard words are not so hard as they look. Then you will pass into 19another class and begin another book.

I hope that I shall be good friends with all of you long before then – even with the curly little person in the front desk.

And now, just before I stop talking about myself, I want you to look once again at the words which stand at the top of this lesson. Take care of me, please, and cover me with brown paper. I do not want to look old and torn before my time.

Every instruction of that lesson was taken in with wide-eyed wonder and on arriving home that evening with my shiny new book, the job of covering this treasure and all our other books was a major undertaking of primary importance. Because all the other books, which may have been in use for years, were still new to whoever was to use them this coming year, they too had to get a fresh new coat.

The choice of outfit was limited. Usually the first choice was brown paper, which had to be carefully cut into shape with scissors. These scissors, though not my mother’s best, which were kept in her sewing machine for dress-making, came with a health warning and firm instructions: ‘Mind your fingers;’ ‘Don’t stick that scissors into your eye;’ ‘Don’t cut the cover of the book.’ If you failed to follow these orders properly, the scissors were smartly whipped off you by an older sister who deemed herself more capable of fulfilling the requirements. Sometimes a battle for supremacy took place which brought another sister on board and a power struggle ensued with no possible solution in sight until a peace treaty was negotiated by my 20mother, who constantly poured oil on troubled relationships in our female-dominated household.

The brown paper had arrived during the year wrapped around messages from town and had been carefully saved by my mother with this very purpose in mind. Sometimes paper bags containing meal for the animals or chicken feed were taken apart, cut up and reused. This slightly crumpled paper had to be laid out on the table and the wrinkles eased out with the palms of our hands, or, if the paper was in a very wrinkled condition, the iron was brought into action. The iron at the time was a lethal contraption with an inner space that was entered through a back door with a smaller iron, which had been previously thrust into the fire where it remained until glowing red. Then it was picked out with a long, iron tongs and eased carefully into the back of the iron. One false move would have dire consequences. When ironing clothes, the hotter the little ‘red divil’ was the better, but with brown paper a lesser degree of heat was required, otherwise the precious brown paper would crumple and singe into a shadow of its former self. If this disaster struck, the leading general of the book-covering squad was quickly swept from power and a more capable pair of hands put in charge.

The aim was to cover four books from a standard sheet of brown paper – of course that depended on the size of the books to be covered. The sheet of paper was spread out on the kitchen table and four books laid out on top of it. It took a lot of juggling around with different-sized books to 21get the most coverage from one sheet of paper. It was highly desirable to allow sufficient paper for a deep overlap to go inside the cover. If the overlap was too skimpy, the book could slip out of its jacket. This was the era before sellotape came to solve that problem.

If the parlour or one of the bedrooms had been wallpapered earlier in the year, your book could finish up with a matching coat of the same wallpaper. And sometimes we resorted to using other available jackets for our schoolbooks. Testament of our resourcefulness is evident today in my box of books because now, many years later, one of them is still wearing a coat proclaiming Lemon’s Pure Sweets; Lemon’s was a Dublin sweet company of the time. This box must have come from the local shop and been taken apart because it was sufficiently pliable to be moulded into a jacket for a schoolbook. As a last resort, the Cork Examiner newspaper was sometimes brought into action.

When they were covered, we put our books in their new jackets on a chair and sat on them to flatten them into their new attire and mould a better fit. Later that night, when adults gathered around the fire, the books that were not completely flattened were placed beneath bigger, heavier bottoms to mould a total union between book and cover. A well-flattened, firmly-covered book fitted neatly into our school sacks, as we called our schoolbags, but more important still, it was better able to survive the ordeals of the year ahead. And, as well as that, when your books were all kitted out in matching covers there was something 22deeply satisfying in standing back to admire your neat stack of books. These firm, new jackets kept the books safe in our school sacks as they journeyed on wet and windy days, going back and forth across fields and over ditches. And on some occasions sacks could be abandoned when more interesting pursuits distracted us, and they might be forgotten on muddy ditches where they could be left to soak in heavy showers of rain. So our schoolbooks had to be well buttoned up to cope with all kinds of weather eventualities.

23My new book got me off to a flying start: two of the poems caught my attention immediately as they were about a subject very close to my heart – the fairies.

Chapter 3

Fairyland

Growing up in an Ireland where fairyland was part of the landscape added an extra dimension to life, especially for us children for whom nothing was outside the realm of possibility. In our world, fairies were capable of doing anything. The fact that a leprechaun (lepracaun) or ‘elf man’, could lead you to a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was an amazing opportunity to be grasped if the chance ever came your way. Catching a leprechaun would be like winning the Lotto in today’s world, and you could never rule out the possibility that it just might happen. So a poem about him in my new book was very exciting. 25

26

The Fairy Shoemaker

I caught him at work one day, myself,

In the castle-ditch, where foxglove grows –

A wrinkled, wizened, and bearded elf,

Spectacles stuck on his pointed nose,

Silver buckles on his hose.

The rogue was mine, beyond a doubt,

I stared at him; he stared at me;

‘Servant, Sir!’ ‘Humph!’ says he,

And pulled a snuff-box out.

He took a long pinch, looked better pleased,

The queer little Lepracaun;

Offered the box with a whimsical grace –

Pouf! he flung the dust in my face,

And, while I sneezed,

Was gone!

William Allingham

Just beside our farmhouse, as in many other farms around the country, was an old fort and we grew up with an awareness of this historic place, which was a series of rings around which my father had planted trees beneath which we constantly played. My father had historical explanations for the origins of this fort, but we much preferred our old neighbour Mrs Casey’s stories about the fairies or the ‘little people’ who lived there. To us these unseen people were as real as the farm animals and our constant dream was to take one 27of them by surprise and have a chat with them. So when poems and stories about fairies appeared in our schoolbooks it made that possibility seem more attainable.

The poems and stories in our books confirmed our belief that the elf man was not very friendly, though we knew there were good fairies and bad fairies. We were a little bit in awe of them all, and a little scared of the elf man. The fact that in my new schoolbook someone had actually taken a little elf man by surprise and had chatted with him was fantastic. Maybe we too could do that!

The Little Elf Man

I saw a little elf man once,

Down where the lilies blow.

I asked him why he was so small,

And why he didn’t grow.

He slightly frowned, and with his eye

He looked me through and through.

‘I’m quite as big for me,’ said he,

‘As you are big for you.’

John K. Bangs

This poem was illustrated with a black-and-white drawing of an elf and a little girl, which I decided had to be me. And, unfortunately, despite all the instructions about taking good care of this new book, I made efforts to improve on the illustrator with red crayon! 28

29

30Mrs Casey had an implicit belief in another world peopled by beings of whom we had no understanding. This was the era of home births, and she helped the local midwife bring each one of us into the world. On one such occasion on his way into town to collect Nurse Burke, the midwife, my father as usual alerted Mrs Casey to the forthcoming event. She lit a candle and proceeded down the boreen from her cottage to our house bearing the candle aloft, and on arrival told my mother, ‘They came with me when I had the blessed candle.’ ‘They’ could either be the souls of departed Taylors or the little people from the fort, as all were encompassed in her world. I always think of her when someone quotes these lines from Hamlet:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

She constantly told us that the little people helped us to do some of our farm work – an announcement at which my father smiled in amusement, but still, he never interfered with the land in and around the fort and fenced it off so that the farm animals did not have access to it. Many farmers who had old forts on their land followed this practice and thus preserved these historic places which are part of our heritage. Also, tales abounded of the bad luck that came the way of families who interfered with these places, so the people of the time had great respect for that unknown world. But for us children this world gave rein to our imagination and 31when we played in the fort we felt sure that around us was another hidden world, and even though we could not see them the fairies were keeping a wary eye on us. So when we learned poems in school confirming the magic abilities of the fairy people, we were delighted.

A New Year Call

A fairy came to call me

At twilight time to-day.

He coasted down an icicle,

But said he couldn’t stay

For more that sixty-seven blinks

To Happy-New-Year me;

And wouldn’t take his mittens off

For he had had his tea.

He sat upon the window-sill,

His wings all puckered in,

And talked about the New Year deeds

He thought he would begin;

He said he’d help the fairies more

And bird and flower folk;

He’d teach the kittens how to purr

And baby frogs to croak.

This year, he said, he’d practise up

His fairy scales and sing

The woodland world all wide awake 32

By twenty winks to Spring;

He’d never tease the butterflies,