Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

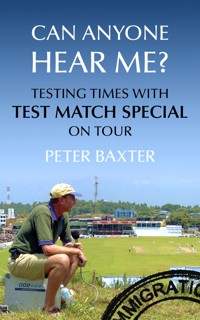

For 34 years from 1973 Peter Baxter was BBC producer of the hugely popular Test Match Special, and during that time he reported on Test matches from around the world. This funny and revealing book takes us behind the scenes as Baxter and his much-loved TMS colleagues do battle with local conditions and sometimes bizarre red tape to bring back home the latest news of England's progress (or otherwise) on the field. It should have been straightforward, but somehow it rarely was...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 511

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the UK in 2012 by

Corinthian Books, an imprint of

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in 2012

by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-90685-049-4 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-90685-050-0 (Adobe ebook format)

Text copyright © 2012 Peter Baxter

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

For Claire and Jamie –

With apologies from such an absentee father

Contents

Title page

Copyright information

Dedication

Introduction

1. The Mysterious East

2. The Lands Down Under

3. The Best Tour

4. The Caribbean

5. The African Experience

6. The East Revisited

7. The Commentaries

8. The Teams

9. The Talk Sport Years

10. The World Cups

11. The Conclusion

Index

Introduction

On Christmas Day 1972 England won a Test match in Delhi. I was staying with my in-laws and trying to find out what had happened in the match. It was not always easy to do so in the days before the internet and rolling news networks.

There was no Test Match Special on that series. In fact, since the retirement from the BBC staff in September that year of Brian Johnston, there was no BBC cricket correspondent at all at the time. The reports on the tour were done – on a rather hit-or-miss basis – by Crawford White of the Daily Express, when he could find a phone. Communications from India were not that good in those days.

I had then been at the BBC for seven years and in my frustration I vowed – I suppose rather arrogantly – that if I were ever to become the cricket producer I would make sure that this situation never arose again. I certainly didn’t imagine that in three months time I would, indeed, be asked to be cricket producer.

My predecessor, Michael Tuke-Hastings – who had been doing the job since before the concept of continuous commentary on a combination of radio networks under the title Test Match Special – had grown bored with cricket. So, in early 1973, the head of Radio Outside Broadcasts, Robert Hudson, took the bold step of inviting this 26-year-old to take over.

A producer’s job can encompass many things. In television, with more elements (and more people) involved in broadcasting a programme, the duties are, of necessity, more cut and dried. In radio, and particularly in the world of outside broadcasts, anything it takes to get that programme on the air is your responsibility.

A great deal of this is inevitably more administrative than creative. You are the BBC point-of-contact with the relevant sporting body and the ground authority. When I started, negotiating the broadcasting rights was part of the job. These days the rights have become such a huge business that the producer will be only marginally involved.

Commentators have to be selected and briefed, commentary boxes have to be checked, renovated or sometimes built, and all the technical arrangements must be made with the engineering side. Billings have to be written, the fine details of planning and presentation have to be worked out with the host network, and listener correspondence has to be dealt with. In my first couple of seasons in the job, I was very much a one-man band, laboriously typing out all the commentators’ contracts myself.

Apart from the Test matches and international cricket, there is the coverage of the county game to be dealt with too. Matches have to be selected. In the seventies we would probably have had commentators at three championship games on a Saturday afternoon so engineers, scorers and broadcast lines had to be arranged for each of those. At least technical arrangements have become much simpler in that area, with the advent of the more flexible dial-up ISDN lines.

At a Test match itself I used to say that the job simply requires getting on and off the air on time and making sure the needle on the meter registering the outgoing sound keeps ticking in between. There is a little more to it than that. Commentary rotas have to be drawn up, which sometimes involves negotiation with those who have other duties to fulfil. Intervals have to be filled with interesting and appropriate subject matter. Frequently decisions have to be made about what to do in the event of bad weather. Sometimes a quiet word may need to be had with a commentator about his reluctance to give the score or recap often enough. When it is all ticking over nicely, you might be able to find a spot to settle at the back of the box to deal with the administrative details of the next Test match.

Just after I was appointed cricket producer, there were considerable changes to the way sport was covered on BBC Radio. The amalgamation of Sports News with the Outside Broadcasts department transformed several job descriptions. Presenters who might have relied on other people’s scripts were now expected to write their own. In other cases the use of a script at all was a new approach – the old-school outside broadcasters scorned reading a report. Much more emphasis was placed on interviews and frequently it was reckoned to be part of a producer’s duty to do these himself. Everyone was expected to be capable of doing any part of the job.

By the next winter after my appointment, the BBC also had its second cricket correspondent – Christopher Martin-Jenkins – and at the start of 1974 he went off to the West Indies to cover England’s tour there. We took little commentary from that, though when it became apparent that Mike Denness’s team were going to win in Trinidad to square the series, I did persuade Radio 2, the vehicle for sports broadcasting in those days, to carry the local commentary that included CMJ.

Up to that time the only guaranteed commentaries from overseas tours were from Australia, usually just for the last session of play and accompanied by all the whistles, bangs and general mush of the old Commonwealth Pacific cable (COMPAC). Many people of my generation remember listening under the bedclothes to just such an imperfect broadcast in the early morning, or shivering by an old-fashioned radio, waiting for the valves to warm up.

Until Sky took up the mantle in the nineties, television coverage from overseas was a rarity. BBC television did broadcast the 1987 World Cup in India and Pakistan, and mounted highlights programmes from Australia, though they were often broadcast so late at night that the next day’s play would already be underway. The editing by Channel Nine for an Australian audience was frequently none too sympathetic to an English point of view, either.

Meanwhile, with a new young cricket correspondent and increased radio sports coverage, I was making a priority of improving our reporting from England’s overseas tours. When we did take commentary, it was by arrangement with our opposite numbers in each country, who would include our man in their team on a reciprocal basis.

That mould was broken in India. New Zealand went there in late 1976 and with them went the New Zealand commentator, Alan Richards. Included in the All India Radio commentary team, he commented on some of the more outrageous umpiring decisions that went against his countrymen. An edict went out from All India Radio that never again would they include a visiting overseas commentator in their team.

England arrived in India hot on New Zealand’s heels accompanied by Christopher Martin-Jenkins, for his first tour of the sub-continent. Tony Greig’s team won in Delhi and then in Calcutta and when it became apparent that they might seal the series in Madras, my suggestion of carrying commentary was approved.

With the All India Radio ban on visiting commentators, CMJ had to raise a commentary team in very quick order, fortunately finding Henry Blofeld, who was there for the Guardian and Robin Marlar of the Sunday Times. And so Test Match Special came live from India for the first time.

That seemed to spark an increase in the amount of commentary we took from overseas – still usually on the basis of joining the local broadcaster.

Don Mosey and Henry Blofeld mounted a Test Match Special from Pakistan in 1977. That was another place in which Alan Richards’ presence had fostered reservations about shared commentary. On that occasion, Radio New Zealand had been carrying the local output and Alan had done the second 20-minute description of the opening day of the first Test. He finished, as he had been instructed by his hosts, by handing on to the next commentator, who thanked him in English and then launched into 20 minutes of commentary in Urdu. Back in Wellington all became pandemonium as they wondered what on earth had happened to their broadcast.

It was more BBC politics than practicality which drove the decision to send a producer on an England cricket tour for the first time in 1981. In fact, my brief then was more to do the news reporting, ‘Oh, and you can also produce Test Match Special.’ Up to that point my touring involvement had been all the logistical support – booking lines and any commentators that might be needed and liaising with my opposite numbers in the various countries, many of whom became friends long before I met them. Then there were the overnight or early morning vigils in studios in Broadcasting House, anxiously waiting for lines to appear and filling in when they didn’t. Going on a full tour myself would be a very different story.

The working relationship of a producer and his correspondent is probably never closer than on tour, even when the producer is thousands of miles away in a London studio. In the last fifteen years of my BBC career the cricket correspondent I travelled the world with was Jonathan Agnew, who always took to the touring life and could usually be relied on to uncover the quirky side of things. Before him it was Christopher Martin-Jenkins, whose career as BBC correspondent had started pretty much in parallel with mine as producer.

Christopher had revolutionised cricket reporting with concise, thoughtful summing up – a fact which might amuse his more recent colleagues who were more used to a cavalier relationship with the clock. At the time of writing, he is fighting a battle against a serious illness, in the course of which, the absence from the Test Match Special box of his companionship, the detailed, easy commentary style and, yes, the idiosyncrasies, has been felt by all.

When I first went on tour – to India – I decided to keep a daily diary of my experiences. That became a habit over the next quarter of a century as I visited all the Test-playing countries and battled to get Test Match Special on the air from them. In this book I have used selected extracts from these rather battered notebooks, which still bear the scars of their travels, to give a taste of life on an overseas tour.

Freed from most of the office work, I was able to concentrate more on the cricket. Production really did become a matter of getting the programme on the air by hook or by crook. In 25 years, I only had the luxury of an engineer travelling with us on two occasions, so my rudimentary technical abilities were hastily learned and often severely tested. As if that wasn’t enough, any of the other radio disciplines might be required at any time. Reporting and interviewing were expected. When there were not enough ball-by-ball commentators available, that had to be done. Sometimes a scorer might fall by the wayside, so I might have to take up the pencil myself. And in many places the role of diplomat and negotiator was required.

Looking through these diaries years afterwards, I find incidents which I had misplaced in my memory and some which I had totally forgotten – though there are others which are all too painfully clear in their detail! I can see how my major preoccupation was always with sorting out the tortuous problems of communication.

It is difficult nowadays to remember life before mobile phones. We take it for granted that we can get in touch with anyone, whenever we need to. That was far from the case in 1981. Recent technical advances have improved not only the ability to get through, but also the sound quality when we do. In those days we put up with extraordinarily scratchy broadcasting lines, which would probably not be allowed on the air now.

Thus the rather anguished title of this book – Can Anyone Hear Me?

Peter Baxter, 2012

1. The Mysterious East

A track wound between some large bushes. Brightly coloured shamiana canopies stretched over bamboo poles appeared through the undergrowth. And between them I could make out figures clothed in white. Thus, in an unlikely clearing in the grounds of a maharaja’s palace, I caught my first glimpse of an England cricket team playing abroad.

It was November 1981 and my predominant emotion was one of relief as I came down the track in the grounds of Baroda’s Motibaug Palace, 36 frustrating hours after my arrival in India. What I found was a scene almost reminiscent of Arundel. For the previous day and a half I had felt fairly isolated, so to be suddenly surrounded by the familiar faces of the travelling press corps was a wonderful moment.

I had landed at Bombay at two in the morning the previous day. It was a great cultural shock, one that even my previous experiences of such places as Singapore, South Arabia and Kenya had not fully prepared me for.

Everywhere there was a babble of noise and more people than you could imagine. Hands grabbed for my luggage to get me to a taxi – I supposed – and eventually I found myself in the back of a grubby, antique vehicle. Knowing that my flight on to Baroda was not scheduled till the middle of the afternoon, I found a none-too-flashy hotel near the airport.

After a reasonable sleep, I made my way to the domestic terminal to check that all was well with my flight, only to be told that it had left at seven o’clock in the morning. ‘The change was well publicised,’ I was told.

‘Not in Hertfordshire,’ I informed the lady at the desk. She agreed to book me on the next morning’s flight.

I checked back into my hotel (where travellers experiencing such problems seemed to come as no surprise) for an extra night. After trying unsuccessfully to raise my colleague Don Mosey, already in Baroda, on the phone, I sent him a telex message to explain my delayed arrival, though the hotel operator helping me held out little hope. ‘The lines are unclear,’ was his technical explanation. (When I did eventually catch up with Don, he showed me a completely incomprehensible message he had been delivered, which certainly fulfilled the description ‘unclear’, though it had at least given him a clue that I might have arrived in the country.)

Saturday 21 November 1981

Six a.m. found me at the airport, confronting an enquiry desk, where I was told that there was a two-and-a-half hour delay to my flight to Baroda. Would I ever get there?

More doubts were raised when I was informed that my reservation was only on a standby basis. I was 29th on the waiting list and it was not promised to be a very large aircraft.

Fortunately my determination to get on that flight got me to the front of the rowdy crowd around the check-in counter as a very softly-spoken Indian Airlines official read swiftly down the list, and at my name I gave a loud ‘Yes!’ and thrust my case onto the scales.

It was the first time the BBC had sent a producer on a cricket tour, but it was not principally production that had been the instigator of my being dispatched to India.

The decision to send me had come after what had been a momentous year for cricket. Probably until England’s Ashes victory in 2005, 1981 was the pre-eminent year for cricket gaining the attention of the wider public. It had started with Ian Botham in command in the Caribbean, where his tour was blighted by a succession of troubles. Two players had to return home early with medical problems and the replacement for one of them was to cause a Test match to be cancelled.

When Bob Willis pulled out after the first Test, the Surrey bowler, Robin Jackman, was sent out to take his place. These were the days of South Africa’s sporting isolation over the evils of apartheid and Jackman, with a South African wife, spent most of his English winters in that country. He had warned the Test and County Cricket Board of this situation when he was put on the reserve list for the tour and had been told that it was not a problem. But, as he headed for Guyana to join the team, politicians in the region started to stir the pot.

Don Mosey, the often irascible ‘Cock of the North’ (as he liked to describe his position as North of England outside broadcasts producer in the BBC’s Manchester office) had been the BBC’s man on the tour. He was not officially the cricket correspondent, but, since Christopher Martin-Jenkins had left to edit the Cricketer magazine, he had fulfilled much of that role.

A Yorkshireman, Don had come to the BBC in the sixties from being the northern cricket correspondent of the Daily Mail. He had been on the staff for ten years when he at last got the chance to join the commentary team on Test Match Special. His bombast meant that on the whole his London-based colleagues would avoid trespassing on ‘his patch’ as much as possible, a state of affairs which suited Don, who professed a disdain of ‘southern softies’ in general and, as I was to find to my cost, public school educated ones in particular. A journalist of the old school, he relished the English language, a trait that was to manifest itself when I got him to do close-of-play summaries, which he accomplished brilliantly. For all his grumbling, he also relished touring.

When the Guyanese government refused to allow Jackman to play in their country in 1981 because of those South African connections, and with England stating their position as ‘accept the team as a whole or we don’t take part’, Mosey found himself in the most difficult part of the Caribbean for communications, making his coverage of the unfolding news story difficult.

That eased with the move to Barbados, after the Jackman furore had caused cancellation of the second Test, but then came another incident – the sudden death of the team’s coach, Ken Barrington, in the middle of a Test match. At the same time, rumours abounded about the captain, Botham’s, extra-curricular activities.

In London the BBC radio newsroom were not overjoyed with Don’s coverage. Some of the problems, like the difficulties of getting through to London from Guyana, were of course not his fault. But in the case of Barrington’s death, they felt that he should have tipped them off as a warning, even with an embargo, instead of waiting until he was sure the family had been told before he made contact. That approach meant that he was not the first to tell them. When they rang him up to let him know the rumour of the death and he said casually that he already knew, they were not pleased.

The West Indies tour was followed by a sensational Ashes series in England, when Mike Brearley was recalled to the colours to inspire England and their hero, Botham, to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

With cricket such hot news, when the head of Radio Sport announced that Mosey would be our man covering the winter’s tour of India, the news department expressed their concern and began to consider sending a reporter of their own.

It was the sports editor, Iain Thomas, who came up with a solution. Peter Baxter could go to India to take the news reports off Don’s hands and also relieve Don of the worry of getting Test Match Special on the air. The newsroom were happy with that and Don only heard the latter part of the arrangement and probably reckoned he’d been given a bag-carrier. He was content at least for me to do all the player interviews, though he sneered at the modern thirst for them. The only exception to this was Geoffrey Boycott, whom Don insisted on interviewing himself, claiming that Boycott would only talk to him.

There had to be some matrimonial consultation before I accepted the invitation to tour, but in early November 1981 I embarked on an Air India jumbo to Bombay. Sitting next to a charming Indian doctor from New York, I received a few tips about India during the journey, one of the most useful of which was that women would always be more helpful than men if you had a problem there.

Communications were my major concern, but in those darker days there was less pressure of expectation. Within the next ten years, television, with its own satellite technology bringing perfect sound and vision, would change that. Back in 1981 there were places where getting through at all was regarded as achievement enough.

We relied a lot on hotel telephones and the hotel operators themselves quite clearly never expected to get through to London, which in those days, outside the big centres, might as well have been on the Moon. The print press wrote their stories on portable typewriters and then had them telexed to their newspapers from camp telegraph offices at the cricket grounds or the central telegraph office in any town.

On a few occasions, Mosey and I tried splitting forces, with him trying to get through from the ground, while I did the same from the hotel. Indeed, after that first game in Baroda, while he waited with the press bus for the last of the journalists to file their copy before moving on to Ahmedabad, our next port of call, I was allowed to hitch a ride on the team coach to get there more quickly and try my luck in getting through from the new hotel.

It will sound remarkable to today’s touring cricket press that I could do that, but we lived much more in each other’s pockets then, particularly in touring the sub-continent, and that sharing of the team bus was not a unique experience on that tour. Team and press luggage was moved from place to place as one consignment. Of course both parties, particularly the press, were much smaller in number than they were to become 20 years later. After the Test matches started, we picked up a three-man BBC television news crew, one of whom was permanently shuttling backwards and forwards to either Bombay or Delhi, the only places from which they could send their stories.

Anyway, the team’s generosity on this occasion brought me no luck and even on the morning of the one-day international in Ahmedabad – my first TMS production abroad – the prospect for communications looked bleak. Although I had found the commentary box on my visit to the ground the day before, it had been utterly barren. As we were dependant on All India Radio for all our technical support, I made contact with them and was told that no equipment would be arriving until the morning.

To my relief, when I turned up the next day, the box was unrecognisable. Radio engineers bustled about, setting up equipment and, for all that it looked past its best, this was an encouraging sign. I found a telephone in the telegraph office that was set up for the benefit of the press and sent a telex to the BBC sports room to give them the number as a safety measure. (I later discovered that the message actually never got there.)

Mosey arrived from the hotel and Tony Lewis from the airport, having flown into Bombay overnight, so our commentary team was assembling as planned. Gradually, however, my confidence in the communications started to wane. The game started and still we had made no contact with London. I called out in vain, with the antique headphones pressed to my ears, straining for a response. At long last I heard it: a faint and distant voice calling out, ‘Hello, hello.’

This was a breakthrough. I called back, excitedly, ‘Hello Bombay! Can you put me through to London, please?’

The faint voice persisted, ‘Hello, hello.’

‘Come on, Bombay,’ I said, ‘We should have been on the air an hour ago.’

The voice failed to acknowledge me, though continued to call out, to my increasing frustration.

Now Tony Lewis made his first contribution to the tour, tapping me on the shoulder to indicate the turbaned engineer sitting immediately behind me and calling out, ‘Hello, hello.’

The message was conveyed to me that we had no line bookings. As I had all the paperwork, I knew this was wrong, but this was the word from the Overseas Communications Service in Bombay. Over subsequent tours of the sub-continent I became used to this as a standard delaying tactic to put the annoying Englishman on the back foot.

Wednesday 25 November 1981

Play was well under way and we still had no contact with the outside world, when Tony gave me some excellent advice. He muttered that Henry Blofeld had found that a well-timed outburst of indignation and even rage was sometimes quite effective in these parts.

Amazingly, it worked. Within seconds of demanding angrily to speak to the man in charge of communications in Bombay, I was actually speaking to London, where Christopher Martin-Jenkins had been filling time manfully, with readings from a series of telexed scores from the BBC’s man in Delhi, Mark Tully.

As regards the advice about the flash of temper, it’s worth noting that while such tactics are occasionally effective in India, they are thoroughly counter-productive in other places, notably the Caribbean.

England’s win by five wickets in that first one-day international in 1981 was to be their last in India on that tour. Again it is a measure of the way things have changed that I interviewed the captain, Keith Fletcher, in the dressing room after the game. It was the only remotely peaceful place on the ground. While such an entry was always strictly on the captain’s invitation, it became quite normal on that and my next tour of India.

As dusk fell on Ahmedabad that November evening in 1981, with a rabble at his dressing room door, Keith Fletcher was a fairly contented man. That would change over the following weeks, but just then we could look forward to the comforts of the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, to which we were all bound that night, there to prepare for the first Test Match.

As a result of my experience in Ahmedabad, my most urgent mission when we arrived in Bombay was to visit the Overseas Communications Service and go through all our line bookings for the tour with them. These were, after all, the people who had claimed that we had no bookings. Disarmingly, they produced all the paperwork we had exchanged via British Telecom. It seemed they were just reluctant to believe it until they had actually seen someone from the BBC. It certainly taught me a valuable lesson for all future tours: to start with this kind of personal contact. While I cannot claim that everything always worked like clockwork thereafter, it did help immeasurably.

In fact, generally on all my early tours, the first thing to do on arrival anywhere was to make contact with the people who were going to help us get on the air. The problem in some places was identifying the crucial person who was actually going to make it work. In India I would go to the local All India Radio station, there to be introduced to the station manager and his chief engineer, sometimes together, but more usually separately in their offices, in which I would be given a mandatory refreshment – tea in the northern half of the country and coffee in the south, but always syrupy sweet.

After visiting the OCS in Bombay, I went to the All India Radio station, not far from the Test match ground, the Wankhede Stadium.

Thursday 26 November 1981

I found myself ushered into the local commentators’ pre-Test meeting. We sat around the station controller’s office, sipping impossibly sweet tea, until the controller called us to silence.

‘Gentlemen, we must not be biased,’ was his only pronouncement. We all nodded sagely at this great wisdom and the meeting broke up.

I did manage to get a meeting with the chief engineer and some of his staff, but the BBC requirements seemed to baffle them. In particular the need for a telephone for reports at the same time as the commentary was going out was hard to grasp.

I was reminded of the advice I had received on the flight out, that in India women are much more helpful than men, when I met our allocated engineer, a lady called Veena. She seemed to understand immediately what we needed and took me back to the ground to show me where everything would be tomorrow.

The cricket on this tour was fairly dire, though on the first day Ian Botham enlivened proceedings by scything through the Indian batting.

Friday 27 November 1981

Our glassed-in commentary box gave us little of the noise and atmosphere of the occasion, but with tiered rows of chairs in the back of the box, we found we were acquiring a crowd of our own.

‘It’s filling up nicely,’ was Tony Lewis’ comment, as he drew my attention to the massed ranks.

I thought I ought to make enquiries as to who these people were. The first I asked announced herself as the wife of the Director General of All India Radio. I withdrew.

India won that low-scoring first Test by 138 runs, thanks to the spin bowling of Dilip Doshi in the first innings and the seam and swing of Kapil Dev and Madan Lal in the second. In a six-Test series, this was to be the only positive result.

The Test match ended a day and a half early. This had one benefit, in that the BBC, worried about the quality of the microphones we had been furnished with by AIR, had despatched a pair of their own to me. Little did we know when the arrangement was being made, what a rigmarole would ensue.

To start with, I had to meet our local shipping agent at the hotel on the rest day, an occasion which gained me a nickname that has stuck for a generation.

Monday 30 November 1981

I agreed to meet the agent in the hotel foyer and, while I waited for him, a porter came past carrying a board with the name ‘Mr Bartex’ on it. Michael Carey of the Daily Telegraph was keeping me company and, with an eye for a crossword clue, pointed out that this was an anagram of ‘Baxter’. And sure enough, it turned out that it was me he was paging on behalf of the shipping agent.

The shipping agent is at his wits end. He asked me to supply him with a letter for the customs, to reassure them that the microphones will be re-exported after use, which I did. But later in the day he reported that his efforts had not been successful and they remain in their custody. Things were more confused by the customs’ apparent belief that, like All India Radio, the BBC is a government ministry. It looks as if I shall have to go and see them as soon as the Test Match ends.

And so it turned out.

Wednesday 2 December 1981

I took a taxi to the shipping agent’s small office near the airport. The man himself was fulsome in his apologies for the red tape over which he had no control. He took me to the cargo terminal. I picked up the tone of the place from the sight of a pig leaving the building as I arrived.

We entered an office where four rows of seats were fully occupied in front of a man at a desk. We went to the front immediately and the nearest members of the crowd, who might have thought they were at the head of the queue, were ushered away with the peremptory order, ‘Wait half an hour.’

My friend the agent (who never did reveal his name) showed him the shipping order.

‘Passport,’ he snapped.

I showed it.

‘Has he a TBRE?’

My friend looked at me enquiringly – and rather pointlessly, because he had asked me the same question several times earlier and I still had no idea what a TBRE was.

Not for the first time I asked, ‘What is a TBRE?’

‘Downstairs,’ was all the answer I got.

In another office on the floor below we were issued with a form and I sat in the corridor to fill it in with the agent’s help. He took it away with the instruction, ‘Wait five minutes.’

As good as his word, he was back half an hour later, brandishing a wodge of paper. ‘We go to customs hall.’

To get into that we had to call at another office, where the passport and the wodge had to be examined. The paper was thrust back into my hand with the explanation, ‘TBRE!’

Two yards further on, a man in khaki uniform wanted to see it all again. And then we were in the bonded warehouse. There was an ominous line of eight desks, each manned by an official in white uniform. Happily, we by-passed the first seven desks. The man at the eighth predictably started with, ‘Passport.’ Then, ‘TBRE.’

‘Can you tell me what it stands for, please?’

‘Tourist Baggage for Re-Export.’

He stamped the paperwork noisily, but that was not the end of it. We did have to visit each of the other seven desks after all, where the same procedure was gone through. By now, to slow the whole business down, we had to talk cricket at each desk, too.

At the end of the line I was suddenly presented with the package. To my dismay, I had to go back to desk number one to open it. Two microphones of a type I wasn’t familiar with lay inside, with accompanying attachments.

‘What is this?’ said the customs officer, pointing at something that looked like a large screw.

‘God knows,’ said I, though I did better with the next piece he chose. ‘Ah, that’s a windshield.’

The manifest had to be signed and then taken for further stamps all the way down the line of desks again, though the atmosphere was much more friendly. After all, I was becoming an old friend and it appeared that all these people had nothing else on today apart from stamping my paperwork. ‘What do you think of Kapil Dev?’ was the most frequently asked question.

‘We still have the register to sign,’ said my friend, when we seemed to have finished. Even that took four desks to complete.

As we emerged after over three hours in the building, he asked, ‘Why did you ask for them to be sent?’

‘I didn’t.’

And with that I was just in time to join my colleagues arriving at the airport for our evening flight to Hyderabad.

In my early days on these tours, the concept of back-to-back Test matches had not yet surfaced, so between Tests we would usually be in smaller cities for matches against regional teams, which would take place in some interesting venues. The early call on the All India Radio station would be quite a revelation.

In Hyderabad on this 1981–82 tour, I found the AIR station was in the splendidly appointed former guest house of the Nizam, the erstwhile princely ruler, immediately across the road from another of his old palaces, which now housed the local government offices. Several years of broadcasters’ occupation had taken some of the lustre off the guest house, but you could get some idea of its previous glory.

Here I met what we believed to be the world’s first female cricket commentator. She was Chandra Nayudu, daughter of India’s first cricket captain, C. K. Nayudu. She was elegant and softly spoken and contemplating the start of what was only her fourth commentary in five years.

The next day I found myself invited to sit alongside her in the AIR commentary box to help her with the names of the England fielders.

Much later in the tour, we were in Indore in the centre of India, where the local AIR station was more prosaic than the Nizam’s guest house. I found that I was expected there.

Thursday 21 January 1982

The radio station was a bungalow on the outskirts of the town and at its gates I found the entire staff drawn up for my inspection. I had to pass down the line like visiting royalty inspecting a guard of honour.

Friday 22 January 1982

Our day at the Nehru Stadium was enlivened by the quickest century I have ever seen. Ian Botham had made it pretty clear to the press the previous evening that he reckoned playing in these provincial matches (this one was against Central Zone) was a waste of time and warned that he intended to alleviate his boredom with some fireworks. He reached three figures from 48 balls and his whole innings of 122 occupied only 55 balls. It contained seven sixes and quite a few of his sixteen fours fell only just short of the boundary rope.

I now had a good story to report at the close of play and so I made my way up to the AIR commentary box on the floor above the press box. For half an hour we tried unsuccessfully to raise London. After that time the engineers suggested that we would be better off trying from their studios at the radio station.

Arriving at the AIR bungalow I was proudly told, ‘We have allocated you our best studio. This is our music studio.’ However, when I saw this jewel in their crown it became apparent that I would not have any two-way communication from the studio itself, but only from the control room telephone before I went in. The first part of the line to London had just been established, that being the rather shaky microwave link to Delhi. The operator there enjoyed an over-indulgence of their habitual ‘hello, hello’ routine and then, when I was at last speaking to London, interrupted several times with the command, ‘Speak to London,’ until he received a good blast of Anglo Saxon from me, which hugely amused the engineers at my end and shut him up for good. After this I was taken into the pride of AIR Indore – the Music Studio.

I was shown into a large, square, heavily carpeted room. It had not a stick of furniture in it, save for a microphone on a short stand in the middle of the floor. The intention was that I should sit on the floor – presumably cross-legged, as if playing the sitar – to deliver my reports. I described the scene to the London studio, before embarking on my accounts of Botham’s remarkable innings.

As soon as we arrived in Jammu, up in India’s north-west, close to the border with Pakistan, I went with a party of journalists to locate the central telegraph office in the town.

Tuesday 15 December 1981

The CTO was a remarkably small office with bat-wing doors like a Wild West saloon. Even the browbeating given to the staff by the Press Association’s man looked unlikely to bear much fruit.

Wednesday 16 December 1981

At the huge, wide-open concrete saucer of the Maulana Azad Stadium, things looked a little more promising. In the open compound of the stand set aside for the press there were a couple of telephones. The newspaper correspondents were less impressed. There were telex operators, but no telex machines. The press’s tour leader is Peter Smith.

‘We were promised three machines,’ he complained.

‘Oh sir, there are three machines. One telex three kilometres away and two men with bicycles.’

I may have chuckled at that, but I was in just as bad a position. Those telephones flattered to deceive and we two from the BBC went for four days without ever making contact with London. It was only later that I discovered that London had been kept up-to-date by reports from the celebrated Delhi correspondent, Mark Tully. One writer’s copy did get through – to a clothing factory in Lancashire, where it was discovered when the staff returned after the weekend.

I did have one moment of excitement when the press box phone rang on the second afternoon. The operator handed me the receiver and a faint voice asked me to record a report. I did so rapidly, terrified of losing the line, but when I asked to speak to the editor afterwards, the voice at the other end told me I was getting faint in a way that made me suspicious. I looked round the press box and saw the Daily Mirror’s seat empty. Sure enough within a minute, emerging from the pavilion on the far side of the ground and whistling in triumph, came their correspondent, Peter Laker. In fairness, he had done pretty well to get a call through over even that short distance.

Following that match, an all-day coach journey in convoy with the players’ bus and police vehicles took us to Jullunder in the Punjab for the second one-day international. Even with a police escort and the supposed high status of a visiting national cricket team, negotiating the dues to be paid at the state border we had to cross caused a major hold-up.

Jullunder raised further transport-related problems. These started early on the morning of the match, as I set off for the ground, which I had not had the chance to inspect the day before.

Sunday 20 December 1981

In the rather foggy dawn I left the hotel on, in the absence of any taxis, the back of a cycle rickshaw propelled – slowly – by an emaciated old chap. ‘To the cricket stadium, please,’ I placed my request.

Half an hour later I was a little surprised, therefore, when we arrived at the bus station. Thankfully a women waiting there spoke good enough English to understand me and translated my desired destination to the rider.

Unfortunately it became apparent that the bus station is on the opposite side of town from the Bishen Bedi Stadium, just recently renamed from having been known as Burlton Park.

I was beginning to feel concerned about my frail driver, as well as feeling that I wouldn’t mind a go on the pedals to warm myself up on that distinctly chilly morning. We did cause considerable amusement, though, for the occupants of the England team bus as it overtook us en route for the ground. At least it was an indication that we were now on the right road.

At the ground I found our commentary position on an open concrete platform, which looked to be half constructed (or half demolished – it was difficult to tell which). At least if the chilly mist lifted we would have a good view. Its main drawback was that a ten-foot ladder was required to get to it and there was no such piece of equipment in sight.

After a long wait, a bamboo ladder was requisitioned from the builders (or demolition workers) and I was able to gain access to the commentary point with the AIR engineers who were to look after us. They were puzzled that I was asking for headphones, as they insisted that we would not be able to hear anything from London. The fact that we might need to hear from London to get on the air in the first place did not seem to have occurred to them.

While they wrestled with that conundrum, I went to book my telephone calls for Radio 2 on a phone kindly lent by the local television service and situated just below their platform, which was next to ours and sharing the service of the bamboo ladder. Though the calls all came through on time, the summoning of the ladder wallah every time I needed to get down to the phone provided some delay.

The return circuit from London did appear – to the astonishment of our engineers – and we were able to have a rare conversation with the studio, as well as hear the cue to get on the air.

Each new location on the tour brought with it tales of doom and gloom from those members of the press party who had been there before, usually concerning the hotel. In Jullunder it was the wholly inappropriately named Skylark Hotel, where I shared a large and very shabby room with the correspondent of the Evening Standard, the late John Thicknesse, who was to become, over several tours, my most regular room-mate, whenever it was required. On this occasion I can remember drifting off to sleep after our arrival to the sound of the card school he had set up with Mike Gatting and others.

Our time in Jullunder had come after Jammu, where the winter chill necessitated electric fires in the rooms. You had to ask for these at reception, after which one would be obligingly provided in your room by the evening. However, there were not enough to go round, so the next day you would find that your fire had been removed to the room of someone else who had asked.

Later on, the Hotel Suhag in Indore was plagued by power cuts, frequent enough to make the use of the lift something of a lottery and by the end of our time there we were all resisting the blandishments of the hotel staff as they beckoned us towards it.

The third one-day international was staged in the eastern city of Cuttack, which apparently had no suitable hotel accommodation. So we all stayed an hour’s drive away in Bhubaneswar, where we had to be spread over a selection of hotels. It was here in Cuttack that the Indian batsmen easily disposed of a fairly average target to secure the one-day series two-one.

Wednesday 27 January 1982

After the press party had got through the problems of repeated power cuts in the telex office, our return journey to Bhubaneswar was enlivened when our police escort decided on a short cut through the back streets of Cuttack. The small jeep leading us shot below a very low railway bridge, which our bus was quite clearly never going to get under. This fact only dawned on our driver at a frighteningly late stage in our rapid progress towards it – and a long time after his passengers were aware of the danger. The failed short cut added about three-quarters of an hour to the trip.

Arriving back in the bigger centres for Test matches was always something of a relief, both on the comfort front and because of the chance to unpack completely. This has become more of a problem in recent years for those involved in one-day series, when the routine of travelling, sorting out the logistics and then covering the game before moving on again leaves little time for settling in and often stretches laundry arrangements.

Bangalore’s West End Hotel is spread through delightful gardens, in which my ground floor room was to prove handy for Tony Lewis, whose hotel had run out of hot water. He was able to climb over my balcony railing of a morning to come for a shower. He repaid me with dinner at his hotel. ‘You must come and hear the world’s worst saxophonist,’ was his invitation. This judgement turned out to be completely accurate.

In Bangalore the frustration of the England team started to surface on-field, as India determined to sit on their one Test lead through the last five matches. England might be able to make 400 in a first innings, but, with no minimum number of overs to be bowled in those days, India were going to make sure it took them a very long time to get there. Dilip Doshi, bowling off about three paces, could nonetheless take eight minutes to deliver an over. The captain, Sunil Gavaskar, would often stroll from first slip before each ball to consult with his bowler and adjust the field.

The umpiring occasionally raised eyebrows, too – there were no neutral country umpires then. On the second day, after being given out caught behind, the England captain, Keith Fletcher, tapped a bail off with his bat. In the commentary box at the time, our view had been obstructed by the wicket-keeper, but back at the hotel in the evening I found it was all the talk of the press. The BBC news cameraman showed me a replay on his camera, which left me still wondering if it was an act of dissent or disappointment. I put a call in to the BBC in London to record a new piece, as I was sure that this was going to be the headline story in most of the papers – and so it proved.

The third Test in Delhi followed the same sort of pattern – a large England first innings followed by a similar Indian reply occupying most of the five days. But in Calcutta for the fourth Test, the frustration was slightly different. In a comparatively low scoring game, England came out on the fifth morning with a chance of bowling India out to win the match.

Wednesday 6 January 1982

We have all become well aware that Calcutta is one of the world’s most polluted cities. All the residents seem to cough as a matter of course and most of us have picked up sore throats in our week here. In the morning it is quite normal to find smog settled over the city. On the rest day it was well past midday before the sun pierced the gloom, so the England camp was always afraid of this halting their progress. In the event, this morning’s mist was comparatively light and the Sun was able to cast shadows.

However, Sunil Gavaskar, as captain of India, is a powerful figure and again he convinced the umpires that the light was completely unplayable, although we did have the farce, after his initial appeal, of one ball being bowled, which was perfectly middled, before the umpires decided to come off for bad light for an hour and a quarter.

The England players registered their own protest at the decision by staying on the outfield to sunbathe ostentatiously, before they were summoned in by a more diplomatically-minded manager.

Whether England could have won if they had had a full day’s play is of course uncertain, but the delay had also taken any chance of an Indian victory out of the equation.

Calcutta also saw the end of the Test career of Geoffrey Boycott. In Derek Underwood’s words at the time, it was the end of an era.

At the third Test in Delhi, Boycott had become the highest scoring Test batsman in history at that time. With a four through mid-wicket on the first day he had overtaken Gary Sobers’ total of 8,032. On the second day – Christmas Eve, incidentally – he went on to an inevitable century.

I made no diary entry about the fact that Boycott declared himself unfit to field for the last day of the Calcutta Test match. And I did not know until much later that, to the fury of many of his team-mates, he went off to play golf during this period of injury. I can forgive myself a little for the omission, when I see that Wisden’s account of the match also makes no mention of this, though, perhaps significantly, it notes that Boycott began his innings ‘with unfamiliar levity’.

Generally, knowing what I later knew, I see that I missed a few clues along the way, which will become clear. The day after the Test, having agreed with Don Mosey that we would each take an up-country match off during the tour, I was setting off with my wife for a three-day break in Kathmandu. The team and press had left early in the morning by train for Jamshedpur, where England were to play a game against the East Zone.

Before we left for the airport, I was aware of the captain, Keith Fletcher, and the manager, Raman Subba Row (neither of whom had accompanied the team to Jamshedpur) in earnest conversation. The subject of their discussion became apparent three days later when we returned to Calcutta shortly before the bulk of the press arrived. I got a shock when the first of them turned up.

Sunday 10 January 1982

A reference was made to ‘the Boycott story’. Gradually I discovered that I had missed the biggest news story of the tour. At about the time we were landing in Kathmandu on Thursday, Geoff Boycott had been leaving India for England.

I gathered that the official version was that it was ‘by mutual agreement’ with the tour management, though his decision to play golf when he had declared himself unfit to field appeared to have been the final decider.

I felt bad about having been away when this story broke, particularly when I was regaled with tales of the press – Don amongst them – trying to file pieces late into the night in the central telegraph office in Jamshedpur, with rats running round their feet. In reality, of course, I knew that there was nothing extra I could have done.

The real reasons for Boycott’s departure were to emerge at the end of the tour, but for now it just seemed sad that so many of the team appeared glad to see him go.

My wife, Sue, had joined us on the tour just in time for Christmas in Delhi, which fell on the rest day of the third Test match. This was the first of my eleven Christmases on tour. For three others I managed to slip back home just in time.

Coming from an army family, Christmas in a warmer climate was not a completely novel experience for me, but I never got entirely used to the slightly bleak feeling of celebrating the day in a foreign hotel. There was usually a relaxed air about the press party, with no papers on Christmas Day or Boxing Day. There were also few BBC outlets, as most of the programmes – at least until the arrival of Radio 5 Live – were recorded.

Friday 25 December 1981

The day started with a call from Frank Keating of the Guardian to join him for buck’s fizz in his room. Most of the press were there and we moved on in due time to the traditional press drinks party for the team. That broke up when the players went to change into fancy dress for their lunch. The theme had been set as ‘my hero’ and we had glimpses of Geoff Boycott in a commissionaire’s uniform as Ranjitsinjhi, Keith Fletcher and Graham Dilley as two of the cast from ‘It Ain’t Half Hot, Mum’ and Raman Subba Row (the manager) as Kermit the Frog, which has become the team’s nickname for Mr Wankhede, the President of the Indian Cricket Board.

We in the press party were joined for our Christmas lunch by two team wives – Anne Subba Row and Dawn Underwood, who were excluded from the team-only lunch.

After the festive meal, Sue and I slipped away for a guided sight-seeing tour of Delhi. It may be the only time I shall spend Christmas Day visiting a Hindu temple and a Muslim mausoleum – Humayun’s tomb.

Saturday 26 December 1981

Back to work after the holiday. Our Indian colleagues were most felicitous with their wishes for a happy Christmas, although I got a bit bogged down explaining a few times what Boxing Day meant.

On the whole the hotels we were installed in for Test matches were clean and comfortable and sometimes more than that, but our time in India ended in Kanpur, which was something of an unpleasant exception.

Thursday 28 January 1982

In the early evening we landed at Lucknow, from where we were expecting a two-hour bus ride to Kanpur. Press and players were crammed together on one bus, with the Indian team following behind in another. First we were held up by a succession of road works and then because a public bus overtaking the convoy scraped along the Indian team coach. Our police escort gave chase, stopped the bus and dragged the driver from his cab by the hair, to subject him to a sustained beating with their batons. One of his passengers then had to be recruited to drive the bus before we could all move on towards the fairly modest charm of the Meghdoot Hotel in Kanpur.

Friday 29 January 1982

Well before dawn I was woken by a bellowing, rumbling, shouting cacophony, which, when I peered out of the ill-fitting and now rattling windows, turned out to be a herd of buffalo being steered along the main road into town. At breakfast I discovered that my colleagues billeted on the other side of the hotel had a different wake-up call to deal with, as a minaret immediately outside their windows delivered the sound of a muezzin calling the faithful to prayer at 5 a.m.

The AIR station director here told me that our match previews would have to be delivered from their studios in Lucknow, as they had limited facilities in Kanpur itself, but remembering the previous evening’s tortuous journey, I suggested that, instead of going there, we might get the commentary box at the ground up and running on the eve of the Test match – a totally revolutionary idea for them.

The camp telegraph office at the ground – Green Park – constructed out of the usual gaily coloured shamiana canopies, was very helpful and welcoming, at least until I discovered on the first morning of the match that they had registered all the bookings I had placed for telephone reports for Radio 2 as fixed-time telex messages, which were not a great deal of use for radio. So, we missed the first two, but thankfully all went well after that.

They had further problems on the third morning, when it rained …

Monday 1 February 1982

The coloured shamiana over the telegraph office had – as anyone could have predicted – provided limited protection from the elements. As the operators were uncovering their telex machines ready for business, the pools of water overhead started to break through. The result of each deluge hitting a machine was an explosion of sparks, so that soon the tent sounded like the battlefield at the Somme.

That Test match, in common with the previous four, was drawn. The combination of the bad weather and a shirt-front of a pitch meant that we did not even get to the end of the second innings, though at the death we were treated to the lob bowling of David Gower gathering his one and only Test wicket. It was not a bad one, either – Kapil Dev, who was very annoyed with himself for getting caught at square leg for 116.

That first tour was a lengthy affair for me. It was made easier by having my wife join me for almost four weeks of it. However, there was still more than a month to go when she left. After six largely unexciting Test matches, the tour moved on to Sri Lanka, which, after three months in India, seemed refreshingly sophisticated.

At that time it was extremely difficult to import anything into India which might put jobs at risk, so foreign-made cars were almost never seen there. This was the first striking difference when we arrived on her smaller neighbouring island. Our short tour in 1982, centred as it was on the inaugural Sri Lankan Test match, was confined to Colombo and Kandy and in those relatively cosmopolitan places, accustomed to foreign visitors, I found making myself understood very much easier.

After a gruelling three months in India there was a holiday feel about much of our time here, which may have been responsible for England finding themselves in danger of losing the inaugural Test match.

Saturday 6 February 1982

By a quirk of timing, our flight from Madras landed in Colombo five minutes after a flight from Gatwick, which disgorged several players’ and journalists’ wives. The tearful reunions on the tarmac between the two aircraft would have done justice to any film script.

For the first time for three months, the press and the players are in different hotels, a mile apart along the sea front and Galle Face Green, which I look out on from my room. This afternoon it was covered with people flying kites.