23,94 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quiller

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

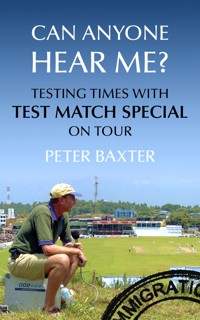

A celebration of three decades of cricket and a unique insight into the world of radio and broadcasting. Test Match Special is both a sporting and broadcasting institution that has become synonymous with the British summertime. Since its first live broadcast back in 1957 it has proudly lived up to its original slogan 'Don't miss a Ball, we broadcast them all'. During much of this time the man behind the scenes was Peter Baxter and here, in this wonderful memoir, he recalls the best moments and characters from his privileged perspective inside the commentary box. Throughout this period, Peter Baxter worked alongside the legendary John Arlott, the inimitable Brian Johnston and the unforgettable Henry Blofield and ushered in new faces, such as Jonathan Agnew, who continue to entertain, inform and charm listeners today. This is the personal, touching and at times, hilariously funny, account of the producer's time 'inside the box'. THE AUTHOR Peter Baxter has spent a lifetime in radio broadcasting, including thirty four years as producer of Test Match Special. Peter Baxter retired from broadcasting June 19th, 2007. Some praise for Inside the Box: 'Excellent memoir... roistering tales of tour exploits'. Independent on Sunday 'From the first page of this delightful memoir we're transported into a world of chocolate cakes, jolly pranks and "the bowler's Holding, the batsman's Willey". 'Bartex', as he was invariably known, was there for it all, and this affectionate recollection is the next best thing to being in the commentary box... for any lover of the summer game, this humorous and affectionate account is an unmissable read'. Daily Mail 'His memoir is as witty and engaging as you would expect - a lovely insight into the nation's most soothing institution'. The Observer '... this book is wonderful. All the larger than life characters we know and love are revealingly described... numerous previously untold tales of their exploits are divulged'. All Out Cricket

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

INSIDETHE BOX

My life with Test Match Special

PETER BAXTER

CONTENTS

Title Page

Foreword by Jonathan Agnew

1 THE END

2 FIRST ENOCOUNTERS

3 OPENING THE INNINGS

4 ARLOTT AND JOHNSTON

5 THE PILLARS OF TMS

6 AGGERS AND THE BOYS

7 THE EXOERTS

8 FAR PAVILIONS

9 DOWN UNDER BEYOND

10 FOREING FRIENDS

11 MUDDIED OAFS AND OARSMEN

12 NEWBURY TO MUNICH

13 2005 AND ALL THAT

14 THE RETURN OF THE ASHES

15 CHAMPAGNE MOMENTS

Index

Copyright

Plates

FOREWORD

I FIND IT RATHER EMBARRASSING NOW TO LOOK BACK and remember just how hard Peter Baxter had to persuade me to apply to succeed Christopher Martin-Jenkins as BBC cricket correspondent. It was during a stroll through Perth’s beautifully manicured Queen’s Gardens that Peter finally convinced me that my future lay in broadcasting, rather than writing for the tabloid Today newspaper. He was right, not least because Today went bust a few years later!

That meeting took place in February 1992 and marked the beginning of sixteen years of successful teamwork and great friendship, to the extent that we were each best man at the other’s wedding.

The relationship between BBC cricket producer and correspondent on long tours away from home is unique. The newspaper writers all operate independently of one another, while Peter and I were a double act, each with our own specific roles. We worked together all day and then, inevitably, met in the bar for ‘a sharpener’ every evening before moving on to eat: I do not suppose that anyone knows me better than Peter, and vice versa.

It has not always been a barrel of laughs. The moment we were held up by armed bandits on the highway between Calcutta and Jamshedpur was only matched by the sinking realisation at Harare airport that we were about to be led to the cells for the night to await deportation. I was sitting next to Peter when the captain of an eventful Indian Airlines flight announced hysterically that we had landed only ‘by the grace of God’ and, of course, we share many painful memories of watching England being stuffed in Australia.

I learned quickly that it was wise to maintain a low profile on the day before a Test match on the subcontinent. It would always start promisingly enough as I waved Peter off to the stadium, rather like a mother at the garden gate seeing her child off to school. Darkness would inevitably have fallen long before a crumpled figure returned with tales of woe and utter frustration having battled with local technicians to establish a broadcasting circuit with London. Miraculously, on virtually every occasion, contact was established the following morning, the only memorable exception being a Test match in Calcutta in 1993 where, as Peter gently noted afterwards in his letter of thanks to the local All India Radio office, the broadcast might have been even more successful had just one of the several engineers they generously supplied been able to speak English.

Too often in life one realises how very special something was only after it has gone. Peter’s gentle (although not necessarily always calm) and low-key attitude to production was such that, once on the air, Test Match Special under his care just seemed to happen by itself. Peter would appear merely to be tinkering about at the back of the commentary box, adjusting the rota or searching for CMJ, but this was his greatest skill. Peter had the nous and the confidence to allow the broadcasters freely to express themselves and to allow their true characters to emerge and to blossom. This probably comes only through experience – and Peter was also blessed with a group of established and formidable cricket commentators in his formative years – but he encouraged the informal and welcoming atmosphere in which a rather quirky, and definitely niche, radio programme flourished and developed into a broadcasting institution.

It is a mark of the closeness of the family of Test Match Special how keenly we all felt the loss of Bill Frindall early in 2009. He was the one member of the team who had actually been there even longer than Peter himself and the commentary box will not seem the same without him commanding his corner.

Time marches on, of course, and I know just how painful it was for Peter to hand over the baton. He leaves behind an army of grateful and loyal listeners who, with an equally determined correspondent, will strive to ensure that Peter’s legacy is merely the beginning.

Jonathan Agnew

The Vale of Belvoir, February 2009

THE END

IT IS 19 JUNE 2007. I AM STANDING ON THE OUTFIELD of the Riverside Ground at Chester-le-Street, County Durham, on a chilly late afternoon that feels more like autumn than high summer, and my time as the producer of Test Match Special has only minutes to run. In fact, it may already have run its course, because Shilpa, my assistant, has told me that I have to be here for some vague reason when, as the programme producer, I would normally be upstairs keeping an ear on the output and an eye on the clock, to bring the programme off the air smoothly at the right time.

However, this, my final Test match in the TMS saddle, has been full of unexpected happenings. There was a presentation from the International Cricket Council, no less, and Jonathan Agnew ambushed me for an ‘A View From the Boundary’ interview. Now on my way down to the field of play, where the presentations for the end of the Test series are about to be made, I have had a remarkable number of handshakes and good wishes. To tell the truth, I am getting a little emotional about it all.

Probably the most touching comment of all has been from Nasser Hussain, one of about twenty-five England captains I have dealt with in my time in office, who has gone out of his way to come over to say, ‘Thank you for all you’ve done for cricket.’ I was really just the producer, getting the programme on the air – somehow.

Aggers is clutching the radio microphone and his few notes, with Vic Marks at his side, and now he is introducing the official presentations, as the Wisden Trophy is handed to Michael Vaughan for England’s decisive victory over the West Indies in the four-match series. Then, after Vaughan has come across to us for an interview, he, too, makes a presentation to me on behalf of the England team.

Finally, I try to get Aggers to present the magnum of Veuve Clicquot for the Champagne Moment. I thought that Paul Collingwood had won it for the moment he reached his century on his home ground, but no, Aggers presents it to me. The Champagne Moment is the moment they get rid of me!

The signature tune, ‘Soul Limbo’, starts up and we are away. Back in the London studio, the announcer, Andy Rushton, credits the commentators and says, ‘The producer … for the last thirty-four years … was Peter Baxter.’

And it’s over.

But how did it happen?

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

LATE IN THE SUMMER OF 1966, I FIRST SET FOOT IN the Test Match Special commentary box. I had not quite completed a year on the staff of the BBC when I was sent to the Oval. My task was to carry out the production role at the ground, the job referred to in those days as the ‘No. 2’.

I cannot remember the first moment I heard Test Match Special, but it would have to have been pretty much at its start in 1957, because by the end of that decade I remember doing what must have been excruciating imitations of John Arlott.

The earliest definitive memory I have of a specific commentary is of me sitting on a splintered wooden step in the Wellington College cricket pavilion in 1963, listening to the closing stages of the Lord’s Test, when Alan Gibson described the tension as Colin Cowdrey came out to save the match with his left forearm in plaster.

Now here I was inside the little hut on the Oval pavilion roof, whose outpourings I had been glued to for years.

John Arlott was there, a legendary figure to me, and with him were Robert Hudson and Roy Lawrence to commentate, and Norman Yardley and Freddie Brown to add their expertise as former captains of England – the Trueman and Bailey, or Marks and Selvey, of the 1950s and 1960s.

The Test match itself was a memorable one. England had appointed Brian Close as their new captain, after a disappointing series against the West Indies had already been lost under Mike Smith and Colin Cowdrey. Tom Graveney and John Murray made contrasting centuries, but the West Indies were finally sunk by a record last-wicket partnership of 128 from John Snow and Ken Higgs.

Even for a nineteen-year-old, working at the match was not quite as daunting as it might have seemed. I had already been in the Radio Outside Broadcasts Department for eleven months, after a three-month spell with Forces Broadcasting in Aden, and earlier in the summer I had been sent out on my first ‘OB’ with no less a person than Rex Alston.

Rex was sixty-five by then and had left the BBC staff, which he had joined during the Second World War, but in his time he had been a sports broadcaster of the stature of Desmond Lynam today. Meeting him in the old radio commentary box at the back of the Warner Stand at Lord’s on 4 June 1966 had been quite a moment for me.

Rex had come to the BBC during the war as a schoolmaster, with an impressive sporting pedigree in cricket, rugby and athletics. Some enlightened soul recognised that he had a perfect radio voice, and he made the transition from wartime billeting officer, his biggest breakthrough coming during a cricket match at Abbeydale Park in Sheffield in 1945, when he was trailing the father of cricket commentary, Howard Marshall. Marshall was summoned to London to rehearse his commentaries on the post-war victory parades, while Rex became inked-in to do the commentaries on the Victory Tests of that year.

There remained an air of the schoolmaster about his commentary, as in his words to the scorer in the first ever Test Match Special at Edgbaston in 1957, when Peter May and Colin Cowdrey were compiling their massive 411 partnership: ‘Now, Jack Price, here’s a problem for you. What’s the highest partnership by a couple of Englishmen in a Test match in England? Can you work that one out … quietly … while Sobers starts the fresh over.’

A low-key county championship match, with occasional reports and snatches of commentary as part of the Saturday afternoon’s Sports Service on the Third Network, with someone as relaxed as Rex Alston, had been the gentlest of introductions for a novice. I cannot remember us being over-taxed by broadcasting demands, although I do recall that at one stage the studio producer announced down the line that they were handing over to us shortly for an update when Rex had popped off down the corridor to relieve himself. For a minute or two I feared I might be about to make my broadcasting debut, but at the last minute a relieved and unruffled Rex returned.

Rex Alston was always ‘Balston’ to Brian Johnston, a nickname which arose from a session of county cricket commentary. In those heady days, for some reason, Edgbaston’s hours of play were always a quarter of an hour behind the rest of the country. So, when Brian reached the close of play in the match he was describing at Lord’s, there were still a few overs to go in Warwickshire’s game. Brian explained this to the listeners and handed over ‘for some more balls from Rex Alston!’ Typically, Johnners continued to enjoy his own gaffe for many years afterwards.

He lured Rex into perpetrating a worse one in 1962 at Lord’s. The Pakistan touring team that year had a player called Afaq Hussain, the first part of the name a commentator’s nightmare in its correct pronunciation, with the ‘aq’ to rhyme with – shall we say – ‘duck’.

Rex was covering the Pakistanis’ match against the MCC in May and Brian had gone along to familiarise himself with the tourists before the First Test. He came into the radio box in the Warner Stand.

‘I say, Balston, this chap Afaq’s a bit of a problem. Let’s hope he doesn’t get into the Test team.’

‘Don’t say that name,’ said Rex. ‘I don’t want it in my mind.’

That was too much of a challenge to be resisted and Brian left the box saying, ‘Afaq, Afaq, Afaq …’

The damage was done and as the Essex all-rounder, Barry Knight, prepared to face the next over, Rex was always alleged by Johnners to have come out with, ‘There’s a change of bowling and we’re going to see Afaq to Knight from the Pavilion End – what am I saying, he’s not even playing!’

In 1985 Rex attended a splendid dinner to celebrate sixty years of the Outside Broadcasts Department. That night he was taken ill and as a precaution moved to hospital. By a remarkable coincidence his obituary for TheTimes had just been updated by his old friend, John Woodcock, the cricket correspondent of the newspaper, and somehow the new version, instead of being restored safely to a filing cabinet in The Times office, found its way into a current tray and into the morning paper.

So Rex was woken in the Westminster Hospital to be greeted by reading his own obituary. He confounded that announcement by having his second marriage announced in the same paper the following year. His wife, Joan, used to recall their meeting at a dinner party, when, following discussion round the table on the subject, she asked him if he was interested in sport.

She reported him responding, ‘Madam, it has been my life.’

For the MCC’s Bicentenary match in 1987, I thought it would be a good idea to mark the occasion by reuniting three of the original TMS team, John Arlott, E.W. Swanton and Rex Alston. Eventually, John decided he could not make the trip from his retirement in Alderney, so we interviewed him on the telephone during the tea interval, but there was a delightful session in the afternoon when the years rolled back and it was commentary by Alston, with summaries by Swanton.

Back in the summer of 1966, when I was sent to the Oval as a producer for the first time, I had a pretty good idea of how these operations worked. I had been in the office that handled all the bookings for radio outside broadcasts, which was a link between production requirements and the technicalities of realising them and, following my earlier visit to Lord’s, I had been drafted into the effort that went into the staging of the football World Cup.

My role for that was an extension of my day job in the OB Bookings unit, operating an office to channel the demands of the myriad foreign broadcasters. I shared a small room in the half-constructed extension to Television Centre in Shepherd’s Bush with Paul Wade, who was eventually to move on to the BBC World Service as a sports producer and later became a sports correspondent at Capital Radio and a travel journalist.

Here we tried to satisfy the facility needs for commentaries, reports and other broadcasts. Thus the office was a lively, noisy, chaotic place as we battled to understand and fulfil all the often passionately expressed requests.

The various commentary teams from South America gave us the most headaches, though their arguments seemed to be mostly among themselves, rather than with us. Paul had the unlikely combination of a phlegmatic air of calm, and a reasonable command of Spanish, both of which came in very handy, as did his sense of humour. We had one extraordinary evening during the tournament, when he and I walked round the corner from Television Centre to help the Uruguay commentary team with their coverage of their country’s match against France at the old White City stadium.

The stadium, once the home of British athletics – and more regularly of greyhound racing – is no more, long since demolished and replaced by a glass and chrome extension of the cash-strapped BBC. Before that fate befell it, my only other visit there was to a rugby league international, more memorable for me as the occasion on which I first met Don Mosey. But that is another tale.

On this occasion, we witnessed an extraordinary three-generation family performance of commentary by a father, son and grandson. One generation did the running commentary, with another providing the expert comments, and the third getting through as many advertisements as he could whenever the opportunity presented itself from a pile of cards, which he kept rotating. The whole thing was conducted at top volume, the trio sharing only two lip microphones between them, so that by half time they were awash with saliva. It was just as well it was all in the family.

My experiences during the year stood me in good stead when I joined the Test Match Special team for the first time. After working so recently at the World Cup final, this was comparatively straightforward. In those days we had only the main commentary box, with no other reporting position. Today’s demands at a Test match will see – in addition to the TMS commentary – a box for Radio 5 Live, and others for the World Service, the Asian Network, Radio 1, Local Radio and, depending on who the visitors are, maybe various World Service language networks or a foreign broadcaster to whom we are offering assistance.

In 1966 the cricket producer for more than ten years had been Michael Tuke-Hastings. He had originally been Michael Hastings, but had acquired the ‘Tuke’ (a family name) because of a clash of names in the BBC. He was once announced at a reception following a quiz programme he was producing as ‘Michael, Duke of Hastings,’ a title which seemed to sit fairly easily on his shoulders.

By this stage he was not greatly enamoured of cricket and felt that he was better placed in the studio, where he could listen to the commentary and compile the highlights tape for posterity as he went along. For the Test matches outside London that was no problem, because for the regional outside broadcasts producers, putting on a Test match was something of a high spot amongst their duties. For Test matches at Lord’s and the Oval, however, someone had to be found to do the production at the ground. It was a popular task, of course, but in a busy summer schedule it might not be too easy to find a fully-fledged producer. Young ‘what’s his name’ – Baxter – from the OB Bookings office would have to do.

I had met most of the engineers, so there was an early welcome from the small shed-like control room across the flat roof behind the commentary hut at the top of the pavilion, where the microphone levels were balanced and contact with Broadcasting House was established.

The commentary box at the Oval in those days was a wooden hut alongside a similar one used by BBC Television, who would have their ‘in vision’ position with members of their team talking direct to camera on the same flat roof in the open air. In that area there was at least one friendly face and someone who was to have a huge influence on my career – Brian Johnston.

Ours was a pokey shed, with a desk built along the front and a wooden slatted bench along the back on which the off-duty commentators and I, as the No. 2 producer, would sit. I wore headphones into which Michael Tuke-Hastings would bark orders along the lines of, ‘Tell Arlott he’s talking rubbish’. It was an early lesson in which instructions not to pass on.

If that was my first encounter with the great John Arlott, I had at least come across Robert Hudson in the corridors of Broadcasting House, without ever getting to know him very well at that stage. Ironically that came four years later when he left regular commentary duties for administration, becoming Head of Outside Broadcasts. He was probably the best-prepared commentator of any that I worked with and had played an important part in the creation of TestMatch Special.

Radio cricket commentary had been going successfully in Britain since the early 1930s, thanks to the brilliance of the pioneering commentator, Howard Marshall, and the vision of two administrators, Lance Sieveking and Seymour de Lotbinière. Even in 1948, when Don Bradman’s invincible Australians toured England, although the BBC mounted full commentary on every ball of the Test series, it was done for the Australian Broadcasting Commission. BBC Radio only joined the commentary for various extended spells. By the 1950s two networks – the Light Programme (the forerunner of Radio 2) and the Home Service (now Radio 4) – were sharing the burden of taking the commentary periods, but these fell well short of covering the whole of a day’s play.

In these days before Local Radio, the Home Service also had periods when the English regions – North, Midlands, South East and West – would carry their own programmes. In the summer these opt-outs included periods of commentary on county cricket. In the late summer of 1955, Robert Hudson was at Scarborough to cover Yorkshire’s game against Nottinghamshire. With forty-five seconds of the commentary stint to go, Fred Trueman was on a hat-trick and Bob was watching the unforgiving clock tick those seconds down as the new batsman took guard. At last Trueman bowled and Poole, the unfortunate batsman, obliged with a catch to short-leg. Bob had just time to shout, ‘It’s a hat-trick! Back to the studio!’

As the North of England’s Outside Broadcasts producer, inspired by this experience, Bob spent the next few months launching a campaign to create Test match coverage of every ball. To do this he proposed the use of the Third Network (later to become Radio 3), which was then a more loosely assembled schedule, though still the home of classical music. The fact that it took eighteen months to come to fruition suggests that there was probably quite a bit of resistance from the classical music lobby, which connoisseurs of BBC politics over the years would easily recognise.

It may well be that a useful nudge was given by Jim Laker in 1956, when he helpfully took nineteen wickets in the Old Trafford Test match. Wherever the final push came from, Hudson’s vision was realised on 30 May 1957, when the whole of the First Test at Edgbaston was covered on a combination of the Third Network and the Light Programme with the slogan ‘Don’t miss a ball – we broadcast them all’ under the new programme title Test Match Special.

Bob Hudson had joined the staff of the BBC in Manchester in 1954, after making his debut broadcasting rugby commentaries on television in 1947, and before that he had held a wartime commission in the Royal Artillery. The television producer who put him on the air was the man who took the same decision with Brian Johnston – Ian, later Lord, Orr-Ewing – who could therefore claim a substantial impact on radio broadcasting.

It was on television, too, that Bob first commentated on cricket, including his first Test match in 1949. He would always come to a commentary having seen as much as he could of all the players involved. He would have a book of notes on them and during the day’s play he would be based at the back of the box during everyone else’s commentary in order to avoid repeating any of the others’ trains of thought.

The lightness of touch in his delivery rather belied this meticulous preparation. Anyone who remembers his description of the closing stages of the Ashes Test at the Oval in 1968 might recall phrases like ‘the second short-leg from the left’, as the close fielders gathered in a ring around the Australian tail-enders for Underwood’s bowling.

I was No. 2 that day as well and I have a vivid memory of the rain hammering on the roof of our little wooden commentary hut so loudly that at one stage I suggested we all keep quiet with the commentary microphones open, while the studio announcer said to the audience, ‘Listen to this’. It seemed impossible that any more play could happen, but Colin Cowdrey, the England captain, mobilised people from the crowd to help with forking the turf and mopping up so that Derek Underwood could bowl out Australia against the clock in the evening.

With so much care taken over what Bob said on the air, the gaffes were rare, but one that he would dine out on happened when a New Zealand touring team was being presented to the Queen at Lord’s. ‘This,’ he declared, ‘is a moment they will always forget!’

Although elevation to the leadership of the Outside Broadcasts Department in 1969 brought a hiatus in Bob Hudson’s sporting commentaries, he still covered some of the great events of state. But for his six-year period at the helm he had a big nettle to grasp in the context of BBC internal politics, as he brought about the amalgamation of the two warring departments which handled sport on the radio: Outside Broadcasts and Sports News.

The huge Sports Department of today, with Radio, Television and the World Service Sport all together, might have happened anyway, but it could be regarded as Hudson’s legacy. So, too, could the quantity of sport available on the radio. In 1969 a document had been published by the BBC called ‘Broadcasting in the Seventies’ – a blueprint for the next decade. The word ‘sport’ was nowhere to be found in it, a state of affairs that Bob found an affront and started determinedly to redress.

In his brief period as Head of Outside Broadcasts, in which his quiet efficiency was in sharp contrast to his flamboyant predecessor, Charles Max-Muller, amongst other major projects Bob had to mastermind radio coverage of the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, the World Cycling Championships in Leicester and the 1972 Olympics in Munich, to all three of which he took me along to work on the planning side.

Bob had only another eighteen months on the BBC staff following the end of the 1972 Olympics. In his retirement he would do talks on his time in broadcasting, concentrating on the royal tours on which he went in the 1960s, including tours to several Commonwealth countries, state visits elsewhere, and the steady procession of independence ceremonies as the British Empire shrank. He was also called back to commentate on rugby union internationals as a freelance. In cricket, I was able to give him a few county matches to report on and he did regular Sunday afternoon commentaries on BBC Radio London, though he used to tell me that the fee barely covered his cost in doing it.

He also continued to be used – quite rightly – as the principal commentator on the major state events. During the time he was Head of OBs and for quite a time afterwards he would do the annual radio commentary on Trooping the Colour, the Queen’s official birthday parade. For several of these years I had the task of recording and shortening the commentary for broadcast on the World Service. I would sit in a studio at Bush House in the Aldwych with a studio manager and we would record the hour-and-a-half ’s parade with its sounds, music and Bob’s commentary. We then had half an hour to reduce it to a half-hour programme.

The trick was to know the running order of the parade inside out and to plan the cuts ahead of time. Most of the military marches are fairly repetitive and it was therefore straightforward enough to cut out the middle of them – provided Bob was not speaking at the time. From the safety of my studio I would curse him for talking across the point at which I was hoping to make a cut.

In those days before digital recordings, we were doing this all on giant reels of quarter-inch tape and obviously at the end had no time to listen through. We would run the edited tape through the timer on the machine, though these were unreliable enough that I would feel the need to do that exercise on all three machines in the studio and take an average timing. The other trick was to leave plenty of the music from the Household Cavalry’s ride-by which always ends the parade, so that the programme could be faded out to time when it took the air.

Once Bob asked me how I got on with this nerve-jangling business.

‘Not too bad,’ I said. ‘You tend to say the same thing at the same point every year, so I know what’s coming.’ I think he was horrified.

I was to work with him quite a bit on various state occasions, surely the biggest being the Prince of Wales’ wedding to Lady Diana Spencer in 1981. Spectacular though the day itself was, the spine-tingling moment I remember most clearly came the afternoon before. Painstaking as ever in his preparations, Robert Hudson was in St Paul’s Cathedral filling in his notes for the big event and I was there, too, in the centre of the cathedral, checking the names on the seats in the prime places, so that when we were covering the arrival for the service we would be able to tell exactly who was who. It was important research because our broadcasting position was looking right down the aisle from the west door, with the congregation facing away from us. Bob would need to recognise the backs of people’s heads, so we needed to plot a chart of the place names.

I was looking up in some awe at the great dome through which Christopher Wren had been lowered in a basket to inspect the construction work – a dizzying thought. The choir was rehearsing an anthem in one of the transepts and I noticed an anonymous young woman in a denim skirt and T-shirt going round casually inspecting the inscriptions on some of the memorials. The choir came to the end of their anthem and the conductor turned and beckoned this girl across. She mounted a small stand and sang, like an angel, ‘Let the Bright Seraphim’. I had to sit and listen to this amazing sound. It was the first time I had heard Kiri Te Kanawa.

Under the dome the sound of choir and soloist in the near-empty cathedral was wonderful. While the music the next day was excellent, it did not quite achieve that electrifying acoustic quality. I was in prime position with Bob inside the cathedral, while outside, perched on Queen Anne’s statue to describe the arrivals, was Brian Johnston. In the build up, as each commentator down the route was setting the scene for the procession, Brian told his audience that, when the carriage reached his position, Earl Spencer and his daughter would probably wave to the crowds and then go ‘up the steps into the pavilion … I mean, St Paul’s!’

It was a wonderful event to be involved in. I had worked with Bob on several other major commentaries, sharing the intimate vantage point in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, for Field Marshal Montgomery’s funeral and the Queen’s sixtieth birthday service, and the roof of the continental booking office at Victoria Station for various state arrivals, but this seemed to be his crowning moment as he made all his carefully worked notes and phrases come alive from the cramped writing on a stack of cue cards arranged in front of him. Radio has certainly not yet come up with anyone to touch him for such descriptions.

Robert Hudson taught me much, but the biggest influence he had on my life came in March 1973, when his secretary came and asked me if I had a moment to pop along to his office. I could not think what I might have done wrong, so I was intrigued rather than worried.

‘Would you like to take over as cricket producer?’ was his opening remark.

I did not hesitate.

Over a cup of tea in Bob’s office, I took over the production duties involved with getting cricket on BBC Radio. That, of course, meant responsibility for Test Match Special.

The main thing I remember about that chat was Bob’s briefing that TestMatch Special was, above all, company for people. He told me then that his philosophy while doing commentary had always been to imagine that he was speaking to one person at home. I rather think he used the expression, which would be thought of as very out-of-date and un-PC now, ‘the housewife at her sink’.

It was suggested to me some considerable time later that the final push towards Bob being prepared to risk this brave appointment of a twenty-six-year-old had come from Brian Johnston, with: ‘Give young Backers a go. I’m sure he could do it.’ It does seem probable that Brian might have wanted some influence and may not have been too happy with at least one of the probable alternatives. However, he was just leaving the staff of the BBC at the age of sixty – a fact which may have helped to prompt Michael Tuke-Hastings’ decision to give up the production of cricket.

I have to confess that I was never a great cricketer. I enjoyed a brief period at my prep school when I started bowling unplayable leg-breaks from a strange, angled run-up to the wicket. But a master took me in hand to coach this talent and, inevitably, I lost it. Later on in my school career, I used to bowl endless and only moderately useful slow-medium rubbish in the nets to get batsmen back into form, though on one extraordinary day, in steady drizzle on a pudding of a pitch, this bowling took eight for 18 with balls that skidded off the wet grassy surface and, I think, a master umpiring who was only too keen to get back quickly in the dry.

In my early BBC career I played some very bad cricket in a scratch wandering side whose main aim was to keep the game going on a Sunday evening until the pubs opened. That was quite an ambition in those days of 7 p.m. Sunday opening and I am quite ashamed of the number of times we failed to make it and had to hang around in a car park, waiting for the doors to open on our first pint. My first wife, not normally given to cruelty, did venture the opinion that it embarrassed her to watch me play.

This may not seem like the ideal CV for what some might imagine to have been part of the fabric of bringing the great game of cricket to the nation and, indeed, the nation to the great game. In my defence, I can only plead a great enthusiasm for what is simply the best of all games.

OPENING THE INNINGS

FOR MY FIRST SEASON AS CRICKET PRODUCER, I WAS given a desk in the office of my predecessor, Michael Tuke-Hastings. We shared the room with his splendid secretary, Brenda Davies. She was a feisty Welsh girl, who took no nonsense from her boss. To some he might have been a domineering figure, but Brenda’s spirit could frequently be overheard down the corridor with a cry of ‘Oh, for God’s sake, Michael!’

She was forbidden to waste any time helping me sort out the administration surrounding my new responsibilities, having to devote herself to Michael’s quiz programmes, but, as he liked to get in early and leave early enough to beat the rush hour, I was offered her assistance from four o’clock in the afternoon. She would wish him a safe journey home and then put his stuff to one side and say, ‘Right, what needs doing?’

If I was pounding my way through commentators’ contracts or Radio Times billings on the typewriter (all carbon paper and correcting fluid in those days, remember), this was always a very welcome offer.

My first big occasion in the new post was the annual departmental cricket meeting. At that time there was an outside broadcasts producer in each of the English regions and, in the case of the North region, two. Don Mosey was the main man there, based in Manchester; Dick Maddock had the Midlands patch, with his office in Birmingham; and the South West was looked after by Tony Smith from Bristol. London and the South East came under the London based producers, but for everywhere outside that area, they needed to talk to the regional producer, because borders had to be respected.

I eventually inherited a large wall map of the country which showed the BBC’s regional boundaries and was therefore a crucial aid. It would reveal, for instance, that the border between the South East and the West actually ran between Brighton and Hove, making Sussex’s county ground a Bristol OB. This was obviously ridiculous, because in those days if engineers were needed for coverage of a match at Hove, they would come up from Bristol and probably stay overnight. Applying some common sense to that one was a battle that it took me quite a while to win.

Tony Smith, the producer in Bristol, would go on later to become Brian Johnston’s producer on Down Your Way. Dick Maddock in the Midlands, with a regional responsibility that took in most of East Anglia and spread to the Welsh border in the west, was a good friend, whose voice became familiar to Test Match Special listeners in the 1970s and early 1980s, when he used to do a great deal of the studio announcing for Test matches.

He had at one time been a television announcer and told of dashing for a bus straight from the studios in full make up and attracting strange looks from his fellow passengers. His office in Pebble Mill commanded a fine view across the rooftops of Edgbaston towards Birmingham University and on his wall was a print of a Canaletto painting of Venice which bore a remarkably unlikely similarity to the view from his window, with the famous Campanile echoed in the university clock tower; a view that came back to me when my daughter, Claire, entered Birmingham University.

Dick Maddock often used to find the Edgbaston Test match clashing with another of his big events, the Royal Show at Stoneleigh, so that I would be invited to handle that Test on the ground, rather than sitting in the studio in London, as I would normally do for Tests outside my patch. His other Test match ground, Trent Bridge, however, he kept very much to himself until his retirement, so that I did not go to a Test match there until 1983.

When doing the TMS studio job, we would have up our sleeves the standby music in case rain intervened. This was carefully selected with one crucial criterion in mind. There must be no rights to pay if we used it. The composers had to be long dead and the performances were all by foreign radio orchestras. Most of the pieces we played in such breaks were therefore not too well known. However, on one celebrated occasion, Dick Maddock proudly introduced ‘The Breton Shepherds’ Dance’ when what came out was the all too recognisable ‘Sabre Dance’ by Katchachurian. Down the line from Lord’s, I enquired of Dick what the Breton shepherds had been drinking.

As I have mentioned, the North region boasted two OB producers. Soon after I joined the department, the senior of these at that time, Tony Preston, made way for his second-in-command – Don Mosey.

On balance it is fair to say that Don did not like me much. We first met at the White City stadium in the late 1960s, when he was producing a rugby league international (that being considered, in BBC politics, a northern game) and I was sent along to lend a hand. I arrived to be welcomed by an incoherent rant against everything generally and everything south of the River Trent in particular. It was so ridiculous that I realised that he had to be joking and dutifully offered a laugh. That just about sent him into orbit in his fury, so that I kept my head down for the rest of the evening.

My next encounter with Don was when I became involved with the quiz programme Treble Chance. It was produced by Michael Tuke-Hastings and in 1968 he found himself short of someone to sit next to the question master and do the scoring. He asked me and I travelled around for a series of recordings of the programme in which university teams pitted their wits against a resident panel. When we visited Scarborough, Don was there to make sure that all went smoothly and the following day gave Michael and myself a lift to catch the train back to London from York.

Having spent his latter years, before he joined the BBC, covering Yorkshire’s cricket for the Daily Mail, Don was very keen to become a TestMatch Special commentator and spent most of that journey cursing Brian Johnston, who in his view had kept him out by dint of wanting only ex-public schoolboys on the team. Michael let Don’s invective flow and I kept quiet again, realising that Don and I were unlikely ever to be bosom pals. In later years I used to remember this when Don would assert that Brian was his greatest friend. (Although he refused to take part in the tribute programme on the day that Brian died, on the basis that I was presenting it.) I knew, too, that Brian would have been horrified to have overheard this conversation and I never told him of it.

It was on one of these quiz programme trips that Brian gave Don his nickname, ‘The Alderman’. After recording a show somewhere in Don’s fiefdom there was a reception in the mayor’s parlour. Brian caught sight of Don across the room holding forth to a group of councillors and felt that he looked a bit aldermanic and the name stuck, to the extent that Don called his somewhat bitter autobiography The Alderman’s Tale.

Brian, for his part, seemed to get on very well with the Alderman, with whom he used to play a word game at the back of the commentary box. Brian’s less ambitious choice of words was generally a winning ploy. When TheAlderman’s Tale was published in 1991, venting Don’s spleen across its pages, it was obviously divisive. I arrived in Birmingham on the eve of a Test match, thinking it would be difficult to share a dinner table with Don. But Johnners made it easy.

Before I had even broached the subject, Brian informed me, ‘I’ve told the Alderman I can’t take salt with him because I’m with you.’

He had declared his position on the book.

The year that I was appointed cricket producer, we were without a BBC cricket correspondent following Brian’s retirement, and Don was pushing hard for that job. In the event it was Christopher Martin-Jenkins who was appointed at the end of the 1973 season, in which he had made his TMS commentary debut, in time for England’s winter tour of the West Indies. Don’s fury burst around Robert Hudson’s ears – not to his surprise.

The ultimate cause of Don Mosey’s hatred of me came in the summer of 1982.

In 1981 he had been to the West Indies to cover an eventful England cricket tour. Ian Botham was the captain, which was newsworthy enough on its own, but added to that a Test match had to be cancelled because of Guyanese government objections to the arrival of Robin Jackman, a man with links to the then ostracised South Africa. Then there was the sudden death of the coach, Ken Barrington, and allegations of extra-marital indiscretions. The News Department were not happy about Don’s coverage of these major stories for them.

That tour was followed by the extraordinary summer of 1981, when Botham emerged from a disastrous spell as captain to take the Ashes series by storm. Cricket was making the headlines and when it was proposed that Don should be our man on the tour of India in 1981/82, there were suggestions that a news reporter might be sent alongside him. A counter suggestion was made by the Managing Editor of Radio Sport, Iain Thomas.

Although we had never before sent a producer on a cricket tour, he proposed that Peter Baxter should go to India to produce Test Match Special and also do the news reports, leaving Don free to concentrate on commentary.

I was asked what I thought of that and said that I was happy – provided that Don was told the exact nature of my brief. I was reassured on that, but such was Don’s irascible reputation, no one ever dared tell him and I always had the impression that he thought I was there to carry his bags. The result was a four-month tour which, while being a fascinating experience for me, was a battle as far as the producer/commentator relations were concerned, coming to an inevitable head at the start of the seventh and final Test of the tour in Colombo, when I was driven to tell him what I thought of him.

He had been contented enough to leave me the job of player interviews – a task he did not care to do at the close of play anyway – with the exception of interviews with Geoff Boycott, whom he reckoned would speak only to him. Although he would then welcome me onto the press bus after a day’s play with a bit of a sneer and ‘Here he is at last, after interviewing all the gate posts and the groundsman’s dog.’

Jullunder in the Punjab was the first place on that tour where the press needed to share rooms in the hotel. Our team leader, Peter Smith of the DailyMail, drew up a list which was presented to us when we arrived at the Skylark Hotel. Don took a look at it and snorted when he saw that, while he had his usual Scrabble partner, Michael Carey of the Daily Telegraph, I was down to share with the urbane John Thicknesse of the Evening Standard. ‘Huh!’ he said. ‘I see the two public schoolboys have been put together.’

My patience with the chips on his shoulder was wearing a little thin, so I responded that we were not the only two on the tour.

‘Who else, then?’ he demanded.

I mentioned a photographer and the correspondent of the Sun: ‘Well, there’s Adrian Murrell. He was at Malvern. And then there’s Steve Whiting.’

‘Where did he go?’

‘KCS, Wimbledon,’ I told him.

‘I don’t count that!’ he said.

‘I’m not sure that I could get away with a remark like that,’ I replied.

Funnily enough, there was to be an echo of this almost a decade later, when Jonathan Agnew became the BBC cricket correspondent. Don approached him during one of his earliest Test matches with us to say, ‘I want you to know that I don’t count you as a public schoolboy.’

Brian Johnston’s amused reaction to this, when a slightly bewildered Aggers told us about it, was, ‘Oh, the Alderman doesn’t rate Uppingham!’

In Jullunder we were covering a one-day international for which the plan had been to use the Daily Telegraph correspondent, Michael Carey, to commentate alongside Don. However we arrived to find a telex telling us that the Telegraph had refused permission for him to do this. Don’s reaction was, ‘I shall just have to do the whole day myself.’

I suggested that I could help him out with the odd ten-or fifteen-minute spell to give him a break. ‘Not an option,’ he declared and in the absence of any backing from London, that is how it was. Don was very pleased with himself at the end of what must have been a gruelling day for him – and the listener – and did not start complaining about how put upon he had been until two days after the event.

We gave each other a match off during the tour. Mine came in early January, when the team went to play in Jamshedpur and I went with my wife for a few days to Kathmandu. Unfortunately that coincided with Geoffrey Boycott and the rest of the touring team settling on a parting of the ways while Don and the rest of the press were not exactly in the communications centre of India.

Later Don took a break at a resort near Madras, while I went to Indore with the team and saw a brutal forty-eight ball century from Ian Botham, on which I reported from the local All India Radio station. This was situated in a rambling bungalow on the edge of town and, when I arrived, all the station’s staff who could be spared were lined up for my inspection. I went down the line like royalty on a state visit and was then shown to their best studio.

‘It is our music studio,’ said the station director, proudly. I entered a large, heavily carpeted room with not a stick of furniture in it, save a microphone in the middle of the floor on an eighteen-inch high stand. I was invited to sit at this cross-legged, in the manner of a sitar player, except with notebook rather than instrument on my lap, and deliver my reports, having first made contact with London from the station’s control room, because there was no facility for headphones in the studio itself.

Early in the tour I acquired a nickname that stuck with me among the press party and players long after its origins had been forgotten. I was standing in the foyer of the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, waiting for a local shipping agent who was to help me import a pair of microphones (an epic performance which is worth a book in itself), when a porter walked past bearing a blackboard on which the legend ‘MR BARTEX’ was written. Mike Carey, who was standing with me, pointed out as it came past a second time that it was an anagram of my name. I tried the bell captain and indeed the message was for me. Over a quarter of a century later, I am often greeted, and written to, as ‘Bartex’.

The Calcutta Test match on that tour gave rise to one small incident when Don said in his commentary, as fruit was being thrown at England’s deep fielders by the spectators, that he did not know why they were wasting oranges in a country where there was meant to be a level of starvation. This was picked up by the Guardian newspaper back in Britain and caused us a sticky couple of days.

We ended the tour in Sri Lanka, where I was asked by one of their radio stations to do some reports on the warm-up games, which led to a mention in one of the local newspapers, which described me as ‘the BBC commentator’. With the inevitable mischief of the press, some of our colleagues drew Don’s attention to this over breakfast in the Queen’s Hotel, Kandy. They were rewarded, as they had hoped, with a Mosey explosion. ‘He is not a commentator, nor ever will be!’ he thundered to any in earshot, which at that moment included me, just entering the breakfast room with no idea what the furore was about.

The following winter, England were due to tour Australia. A new BBC cricket correspondent had still not been appointed to succeed Christopher Martin-Jenkins, who had gone off to edit The Cricketer magazine. I consulted the head of the department, ‘Slim’ Wilkinson, on what plan he might favour.

‘It seemed to work pretty well last year in India,’ he said. ‘Why don’t we do the same again? You and Don go out there and mount your own commentary.’

I said that I would have to give that some thought and agonised over a decision for a few days. Eventually, realising that I was talking myself out of what, for all I knew, might be my only chance to go on a tour of Australia, I told him that I really could not go through another three months on tour with Mosey and he had better get someone else to go. I was sure he would not be short of volunteers.

The next I knew about our winter plans came a week later, when I arrived at Old Trafford on the eve of the Test match there. Don passed me in the car park with a face like thunder and spat out one furious and enigmatic line: ‘You and your public school cronies!’ And away he went to his car.

It was some hours later that Brian Johnston told me that Don had been told he would not be going to Australia that winter. But that was all I knew. I had a Test match to look after and I waited in vain for some word from Slim Wilkinson, who was heavily involved in the coverage of Wimbledon and therefore rather difficult to get hold of in those days before the universal spread of mobile phones. It was not until I was driving home from a washed out final day of the Test that I finally managed to get him on the phone from a call box at an M6 service station.

‘So who is going to Australia?’ I asked.

‘You are,’ he said. ‘You can put together a commentary team there.’

In the event, the use of Henry Blofeld, who was joined by Christopher Martin-Jenkins for the first two Tests, presumably fitted the bill as my ‘public school cronies’, although Alan McGilvray, Michael Carey, Tony Lewis and Jack Bannister might have been a little surprised at the description.

Don Mosey did realise his ambition of becoming the BBC cricket correspondent officially for his last year on the BBC staff, when Patricia Ewing, then the Head of Sport and Outside Broadcasts, took a more sympathetic view than her predecessors, who had, perhaps, not reacted well to the tactics of brow-beating. By that time he had, in any case, covered four England tours, for three of which I had been at the London end of his line.

Amazingly, I do have one memorandum of praise from Don Mosey. In 1976 I was manning the London studio during a Test match at Headingley, when the line went down during the final morning’s play. In those days it would be routed from the north of England through the control room at Pebble Mill in Birmingham, which did make it more vulnerable to something going amiss.

As was the practice, I started commentating off the television pictures for what felt like an age. I even had the wicket of Alan Knott to describe. I could see, through the double glass to my left, the technical operator on the phone and then fiddling with the equipment, before at last he spoke into my headphones. Unfortunately, he had a little bit of a stammer when under pressure and now the pressure was building. However, eventually I got the message that I could hand back to Headingley.

Near silence came from the studio speakers, with just a faint rumble of distant traffic. Then a pigeon cooed alarmingly close to the microphone. I decided that this could be dangerous, because the commentators were clearly unaware we had returned to them. I reopened my microphone and described another over before the voice in my headphones said, ‘You c-can h-have an-nother go’.

I tried again and was relieved to hear the reassuring voice of Brian Johnston. ‘I gather you lost us. We were awfully good while you were away.’