2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

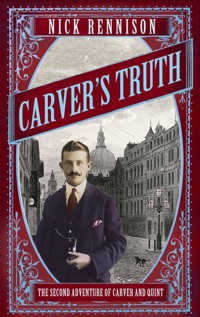

London, 1871. Traveller, photographer and sometime intelligencer Adam Carver is asked by a friend from the Foreign Office to find Dolly Delaney, a West End dancing girl who has been involved with a diplomat and since disappeared. What seems a straightforward case soon proves otherwise. Carver is discomfited to come across alluring daguerreotypes of Dolly and he seeks answers from one of her fellow dancers, the feisty Hetty Gallant. Soon, Carver and his stoical manservant Quint are drawn north to York, where they are implicated in a shocking death. The pair flee across the Channel, but soon encounter new treacheries in Berlin, the imposing and dangerous capital of the nascent Germany. Carver's Truth is both a compelling murder mystery and a splendidly full-blooded portrait of mid-Victorian England.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

CARVER’S TRUTH

NICK RENNISON

DEDICATION

To my family in Berlin –

Wolfgang, Lorna and Milena

PART ONE

LONDON

CHAPTER ONE

The street was not smart but the vehicle which turned into it was. Costermongers’ carts were far more familiar here than broughams, and passers-by stared with unaffected interest at the brightly painted carriage, seemingly fresh from a Long Acre workshop, which came to a halt outside one of the terraced houses.

A young woman, dressed in blue, emerged from the basement area of the house and stepped into the street. She was wearing a veil, also blue, which hid her face from the group of idlers that had swiftly gathered to admire the brougham. Its driver sat impassively on his box seat at the front as the door to the carriage was opened from within. The woman in blue moved towards it, the small crowd parting to let her through. A gentleman in a grey morning suit alighted from the carriage and politely handed her into it, following her into the carriage’s dark interior after she was safely settled into her seat. The door closed, the driver flicked his whip above the horse’s head and the brougham moved off, making its way towards the parts of town where its appearance would cause much less of a stir.

The loiterers on the pavement watched it go and, as it rounded the corner of the street and disappeared, began to speculate idly on the reasons for its visit to their dull corner of north London.

* * * * *

Adam Carver, sometime traveller, intelligencer and occasional photographer, was surprised to see the man from the Foreign Office at the burial of Mr Moorhouse, his long-standing and fond acquaintance from the Marco Polo Club. He could think of no reason why the Honourable Richard Sunman should be there, standing in a remote corner of Kensal Green Cemetery, as the old man’s body was committed to the ground.

It was a cold but bright spring morning and Adam knew why the other people gathered around the newly dug grave were present. The large, middle-aged lady to his right, weeping noisily behind her black veil, was Mr Moorhouse’s niece and sole surviving relative. During their conversations at the Marco Polo, the old man had occasionally spoken of her. Although Mr Moorhouse had been far too much of a gentleman to say anything directly, Adam had gained the impression that his friend had thought little of this niece. ‘Flora,’ he had once said as they were both sitting in the club’s sitting room, ‘is a woman who observes all the social proprieties.’ His tone of voice had suggested that he might have warmed to her more if she had not. Today, Adam thought, her loudly expressed grief sounded much more the result of respect for funereal convention than genuine loss. He doubted if she had seen her uncle more than a handful of times in the last years of his life.

The thin and sour-faced woman on Flora’s right was her companion. Her hand was clutching the niece’s arm as if she was arresting her and taking her into custody. Adam had been mildly surprised to see the two of them. Women did not always, or even usually, attend funerals. Moorhouse’s niece had not entirely observed the social proprieties on this occasion. He guessed that the lives of Flora and her companion were so starved of drama that they could not bring themselves to miss the ceremony, even if the strictest etiquette demanded that they should stay away.

Grouped in a semi-circle to Adam’s left were Moorhouse’s other friends from the Marco Polo. Baxendale, the club’s secretary, was shifting uncomfortably from foot to foot and looking as if he would rather be anywhere else in the world than Kensal Green. Duncan Farfrae – a man whose chief claim to fame in the club was that, as a small boy in Edinburgh, he had once sat on the explorer Mungo Park’s knee – was gazing mournfully into the middle distance. With Moorhouse’s death, he had become the Marco Polo’s oldest member and he looked as if intimations of his own mortality were preying on his mind. There were, perhaps, a dozen other men Adam recognized from his regular visits to the club in Pall Mall. He was surprised that there were not more. Mr Moorhouse, he had always assumed, had been a popular member of the Marco Polo. He had certainly been an almost permanent fixture in its smoking room since before many of the other members had been born. Everyone had known him but it seemed that only a handful of people had been prepared to make the journey to the West London cemetery to mourn his passing.

Sunman had not joined the group around the grave. He was standing some fifty yards away on one of the paths that criss-crossed the cemetery. Whenever Adam glanced in his direction, he appeared to be inspecting an elaborate monument on which two stone angels were playing harps and gazing heavenwards.

It was only when the ceremony was over and Adam, his commiserations offered to the still-weeping niece, was making his way back to the main entrance of the cemetery that Sunman approached. He was immaculately dressed in a black frock coat and looked as calm and collected as he always did. It was as if the two of them had met while strolling along Piccadilly rather than in a burial ground in the further reaches of the London suburbs. ‘Poor old Moorhouse,’ he said, reaching out to take Adam’s hand in greeting. ‘He was quite a friend of yours, I understand.’

‘We met frequently at the Marco Polo. A gentleman of the old school.’

‘He was, indeed.’

‘I had no notion you knew him.’

Sunman waved his hand in the air as if to suggest that there were few people in London he did not know.

The two men began to walk in the direction of the Harrow Road, and Adam found himself wondering just why his companion had engineered this meeting. He had known Richard Sunman since his schooldays but never very well. Early in his Foreign Office career, the young aristocrat had informally recruited Adam, then about to travel to European Turkey, as an off-the-record agent to report on his journeys through this especially sensitive part of the Ottoman Empire. The previous year, on his second and more eventful expedition to that part of the world, Adam had again supplied Sunman with his thoughts and impressions on what he saw. His friend had seemed to set rather more store on them than had Adam himself. However, since Adam’s return from a journey that had ended in betrayal, murder and the extraordinary death of his former Cambridge tutor, Professor Burton Fields, there had been little communication between the two men. Now Sunman, a creature of Whitehall and the West End, had turned up unexpectedly in an out-of-town cemetery. Adam was intrigued, but the man from the Foreign Office gave no indication that he was ready to explain what he was doing in Kensal Green Cemetery. The two of them walked on.

‘Well, would you credit it?’ Sunman came to a sudden halt. ‘I knew this chap. I had no idea he’d joined the great majority.’ He moved to the left of the path and pointed his malacca cane towards a red granite memorial, which looked to have only recently been erected. ‘Well, Pater knew him. I met him. That’s probably a more accurate way of putting it.’

Adam leaned forward to read the inscription: ‘Sacred to the memory of Mr James Henry Dark who died 17th October 1870, aged 76. For many years Proprietor of Lord’s Cricket Ground.’

‘Pater was doing something for MCC,’ his companion continued. ‘Sitting on some committee or other back in the early sixties. This fellow wanted them to buy the lease of the ground from him.’

Adam, who had never heard of James Henry Dark and certainly never met him, could think of nothing to say. His thoughts had returned to Mr Moorhouse, whom he had known and much liked. His companion continued to gaze at the memorial.

‘The paths of glory lead but to the grave, eh, Carver?’ he remarked. He did not sound unduly troubled by the prospect. Perhaps he thought that, in deference to his social standing, he would be excused from treading them.

Adam nodded his head in brief agreement. He was certain that his friend from the Foreign Office had not travelled all the way to Kensal Green simply to indulge in commonplace observations about the inevitability of death. But the languid young aristocrat showed no signs of being in a hurry to divulge his other motives, whatever they might be. Instead, he turned away from the last resting place of Mr Dark and continued to amble along the path.

Adam followed him. The only sounds were the crunching of gravel beneath their feet and birdsong overhead. When a minute had passed and Sunman had shown no sign of disturbing the silence of the burial ground, Adam felt constrained to speak. ‘I am surprised to see you here, Sunman. I would have thought you rarely strayed this far west of town.’

‘I wished, of course, to pay my last respects to Moorhouse,’ Sunman said. ‘He was at school with pater, you know. Sixty years ago.’ He shook his head as if he could scarcely credit the idea of his own father once being a schoolboy. ‘Pater would have been here himself. But the gout . . .’ He shook his head again, leaving it to Adam’s imagination to conjure up thoughts of just how crippling that affliction might be. ‘I did, however, have another reason for travelling out here. What you might call my ulterior motive.’

The two men had now emerged from the main cemetery gate. A black and yellow landau, looking impossibly elegant and out of place, was standing just outside. The coachman, when he saw his master approaching, leapt from his driving seat and hastened to open the door to the carriage. Sunman gestured towards its interior. ‘Let me take you back to town, old man.’

Adam had intended to walk the five miles back to Doughty Street accompanied only by his memories of Mr Moorhouse, but he could see no polite means of refusing Sunman’s offer. He climbed into the landau. His friend gestured in silent command to the coachman and followed him. They settled into the plush upholstery of the carriage’s interior as it began to move in the direction of the distant city.

‘I wished to speak to you in private, Carver.’ As Sunman spoke, he was brushing near-invisible specks of dust from the sleeves of his frock coat. ‘And I knew that you would be attending the interment of our poor friend Moorhouse. The occasion seemed opportune. I thought we could talk on the way back to town.’

‘I am happy to do so. I do not think we have seen one another this year.’ In truth, Adam thought, he and Sunman had not spoken since a brief meeting in St James’s Park shortly after his return from Athens in the autumn of 1870.

‘This is rather more than a social rencontre, old man. Delightful though it is to see you.’ Sunman smiled briefly and perfunctorily, before reaching into one of the inner pockets of his coat and pulling out a photograph. He handed it to Adam. It was a cabinet card showing a pretty blonde woman. She was sitting in a photographer’s studio, holding an unfurled parasol above her head. ‘Her name is Dolly Delaney.’

Adam was puzzled. Why would Sunman be interested in someone named Dolly Delaney? He turned over the photograph. There was nothing on the back of the image.

‘She is an actress.’ Sunman spoke as if he was referring to some exotic species of creature such as a platypus or a manatee that he had heard described but never himself encountered. Perhaps, Adam thought, he hadn’t. ‘And a dancer.’

‘An enticing young lady. Doubtless she graces any stage on which she appears. But why are you showing me her carte de visite?’

‘We wish to speak to her.’

‘We?’

‘Certain people in King Charles Street.’

‘In the Foreign Office?’

Sunman nodded.

Adam remained bemused by the turn the conversation had taken. What possible connection could there be between the upper echelons of government and some pretty ingénue on the London stage?

‘Can you not find her at the theatre where she works?’ he asked, after a brief pause.

‘She has disappeared. She has not been seen at her lodgings or at the Prince Albert theatre for nearly a week.’

‘Why should you and your colleagues be interested in the girl?’ Adam looked at his friend in puzzlement. He waved the photograph that was still in his hand.

‘I regret I cannot tell you why. I can only say it is imperative that she be found.’

There was silence in the carriage. Adam looked again at the young woman on the cabinet card. She was overly made up but she had a pleasant, attractive face. She seemed like a girl with whom it would be fun to while away an evening at Gatti’s or a music hall . . . Adam realized suddenly what linked her with the Foreign Office. Some gentleman there had been doing exactly that. Could it possibly have been Sunman himself? He glanced at his companion, who was staring thoughtfully out of the landau’s window, as if memorizing the route they were taking. Adam decided that he was an unlikely candidate for the role. If Sunman had his affaires de coeur, which he probably did, he would be far too discreet to allow them to impinge on his work for the government.

‘Why are you telling me anything at all about her?’ Adam asked eventually.

‘I have suggested to my colleagues that you might be able to help us in locating her.’

‘I? But surely the police would be able to trace a missing person?’

‘It is better if the police are not involved in the affair. The fewer people who know that Miss Delaney is of importance, the happier we shall be.’

‘But is she of importance? How is she of importance?’

‘In herself, of course, she is not. However, we believe that she is in possession of information that gives her a significance she would not otherwise have.’

‘And what information is it that you believe she possesses?’

‘Alas, that I cannot divulge to you, Adam.’ Sunman smiled politely, almost apologetically.

Adam noticed that Sunman had begun to use his Christian name. Although they had known one another since their school days, he had rarely felt entirely comfortable with the young aristocrat, previously detecting various degrees of condescension in the other man’s conversations with him. He saw now that Sunman, by his standards, was eager to ingratiate himself. ‘One of your colleagues has been squiring Dolly around town, hasn’t he?’

Sunman inclined his head in the faintest of agreements. These were not the kind of words he would use himself, he managed to convey, but they were essentially true.

‘He has been indiscreet in his entertainment of her, has he not?’ Adam almost laughed as he said this. He was rather enjoying the situation. Another thought struck him. ‘The girl is not enceinte, is she?’

‘That would be an added complication, but it is not one that we believe we need to include in our calculations.’

Adam made to hand Dolly’s photograph back to his companion, but Sunman shook his head. ‘Keep it,’ he said. ‘You will need it to help you in your search for the girl.’

Adam took one last look at the carte de visite. She really was a most attractive young woman. He took his wallet from his jacket pocket and slipped the photograph into it. ‘Why have you chosen to ask me to find her?’ he asked. ‘Not that I am not flattered that you thought of me.’

‘We need someone we can trust. We need someone with connections in the – ah – bohemian world in which Miss Delaney lives.’

‘Again I am flattered. Although I am not certain that my life is particularly bohemian.’

‘You have written books,’ Sunman said, as if this was almost sufficient proof in itself. ‘You live in Bloomsbury. You are close friends with that chap, Jardine – who is working as a scene painter in the very theatre where the young woman was last employed.’

‘Perhaps you should ask Cosmo to look for her.’

‘We do not trust him. Whereas, in that unfortunate business in Turkish Greece, you proved yourself entirely reliable.’

Had he, Adam wondered, proved himself entirely reliable? He smiled inwardly at Sunman’s euphemism. The murderous madness of Professor Fields had certainly been ‘unfortunate’ at the very least. He debated whether or not he should accept this dubious commission. Did he truly relish the prospect of tracking down the whereabouts of some missing actress, however pretty she might be? He was not about to set up business as a private enquiry agent. And yet the months since his return from Greece had not been busy ones. Too often fruitless thoughts of Emily Maitland, the girl he had loved and lost the previous year, had troubled him. Perhaps this was the distraction he needed to take his mind away from her.

‘I will do what you wish, Sunman,’ he said. ‘I will look for this elusive young lady.’

‘Capital,’ his friend replied, as if he had never doubted for a moment that Adam would.

‘I assume that,’ Adam continued, ‘however much you may mistrust him, I am free to approach Cosmo with questions about the young lady.’

‘I would suggest that it would be easiest to speak to him before you speak to anyone else.’ Sunman nodded his agreement. ‘Although the theatre is a large one and employs many people. There is the possibility that he did not meet the girl or take notice of her.’

Adam thought about the blonde girl in the photograph. ‘Oh, I believe Cosmo would have taken notice of her,’ he said.

CHAPTER TWO

Adam gazed up at the vaulted roof of the German Gymnasium, its vast timber beams arching overhead. Today, the gymnasium was not as busy as it usually was but there were still more than a score of men in the main hall, engaged in a variety of activities. To Adam’s left, one was swinging himself back and forth on the parallel bars; to his right stood several pommel horses, over which young men dressed in loose-fitting white shirts and trousers were leaping. In the centre of the hall, three pairs of boxers exchanged blows. A railed walkway ran all around the main hall and half a dozen spectators were leaning on the wooden rails, looking down on the athletic activities below.

It was a place he had only recently discovered. Rogerson, an acquaintance from the Marco Polo and a fervent advocate of the philosophy of mens sana in corpore sano, had recommended it to him: ‘Best location in town for a bout of fisticuffs, old boy,’ he had said. ‘Always someone there prepared to go toe to toe with you.’

Adam, however, had disclaimed any interest. ‘I think,’ he had replied, ‘perhaps I had enough of the noble art when I was at college.’

Rogerson had looked surprised, as if it was impossible that any man might tire of the joys of punching another, but remained undeterred. ‘Not just boxing, old boy. Parallel bars, horizontal bars, Indian clubs, wrestling, fencing. Everything to harden the body and improve the mind. All for a negligible fee. You should toddle along and see what they have to offer.’

It was the last activity that Rogerson had mentioned which had caught Adam’s attention. He had fenced for a short time in his final year at school and enjoyed it. He had occasionally, in recent months, thought it would be a good idea to take it up again. Here was the opportunity. He had made his way to the German Gymnasium, built and opened only a few years earlier in Pancras Road, and joined the ranks of its members. In the months since he had done so, he had become a twice-weekly visitor to the place.

‘We have crossed our blades enough for the day, Señor Carver.’ The man with whom he had been fencing bowed gravely in his direction and removed his face mask. Adam unfastened his own and returned the salute. Not for the first time, he wondered about the past history of his fencing instructor. Juan Alvarado was from the Argentine city of Buenos Aires – or, at least, he had several times spoken of it with the easy familiarity of someone who had lived there, but he had been obliged to leave the country and come to Europe a decade ago. His reasons for leaving were shrouded in mystery. Alvarado never spoke of them. Adam suspected that they were connected to the civil wars that had plagued Argentina for most of the decades since its independence from Spain. Alvarado had probably finished on the losing side in one of the many conflicts and decided that it was safer to travel into exile. Adam also suspected that the serious and distinguished-looking gentleman in early middle age who taught him fencing had found adjustment to a new life in London difficult. He spoke English fluently, if occasionally eccentrically, and hinted at the existence of a wife and children living in lodgings in Highgate with him, but he seemed, to Adam at least, a solitary, reserved man who had long ago decided that the best of life was behind him.

Now Alvarado bowed once again and, with the briefest of polite farewells, walked briskly out of the hall. Adam, carrying his rubber-tipped rapier and mask, followed him into the corridor. The Argentine had already disappeared from view. Only rarely did he linger for conversation after their practice.

Adam made his way to the changing rooms. Within half an hour, he was dressed in his own clothes and sitting in the comfortable library which the gymnasium also provided for its members, idly flicking through the pages of The Cornhill Magazine. He came across a fresh instalment of a serial about a character named Harry Richmond and began to read it, but his attention soon wandered. He had read none of the previous instalments and the prose of the story’s author, a gentleman named Meredith, seemed curiously convoluted.

After a few minutes, Adam put the magazine to one side and leant back in his chair. Why had he agreed so readily to do what Sunman had asked of him? The truth was, of course, that he was bored. Since he had returned from Greece the previous autumn, he had had little to occupy his time. The weeks of searching for the gold of Philip of Macedon, which had culminated in Professor Fields’s savage attack, had been difficult and dangerous but never dull. Coming back to London had meant a descent into an everyday normality which he had, he now realized, found hard to endure. He had taken up photography again but the recording of London’s architecture, which had once fascinated him, proved a chore rather than a delight. He had put pen to paper to record his experiences at the monasteries of Meteora and in the hills of Turkey in Europe, but he had discovered that much of the truth about them needed to be omitted, and he had grown weary of the process. His world had all too rapidly become one of tedious routine. He had even begun to ask himself what he intended to do with the rest of life. And then, out of the blue, there was the Honourable Richard Sunman offering him an escape from that same routine. It might, of course, turn out to be the simplest of tasks to find the girl but, for some reason, Adam doubted it. There was more to her disappearance than Sunman was telling him. And whether the search proved brief and easy, or long and difficult, it would be something different to do.

Adam returned the copy of The CornhillMagazine to the rack in which he had found it. He glanced briefly around the almost deserted library of the German Gymnasium. A red-bearded gentleman whom he recognized vaguely from previous visits nodded in his direction. Adam returned the salute and left the library with something of a spring in his step.

* * * * *

A newspaper boy was standing by the gates at the entrance to Doughty Street, bellowing about ‘’Orrible murder in ’Ackney’. Adam stopped to pay a penny for the late-afternoon edition of the Daily News from the urchin before turning into the street. Nodding to the porter in his wooden sentry box, and with the paper tucked under his arm, he walked fifty yards, took out a key and unlocked the door to the Georgian house in which he rented a set of first-floor rooms. Alert to the possibility that Mrs Gaffery might be in residence and intent upon conversation, he took the stairs at a gallop and was in front of the entrance to his own domain within seconds. He had no wish to listen to his formidable landlady expound her ideas on the ills of the world. Mrs Gaffery was a woman who knew her own mind and was not one to allow ignorance of a subject to get in the way of expressing a strong opinion on it. Adam was not always, or even often, in the mood to stand by the door to her rooms, nodding his head repeatedly as she told him what she thought of Mr Gladstone and Mr Disraeli, the recent marriage of Princess Louise, and the reasons why the French could never be trusted.

Safe now, he took a second key from his pocket and let himself into his rooms. As he entered his sitting room, Adam placed his hat on top of the sideboard and threw his coat and the newspaper he had just bought into an armchair. When he heard the sound of wood scraping on the floor in the next room, he realized was not alone.

Adam’s manservant, Quintus Devlin, was already at home. He was sitting on a stool in the kitchen, reading a cheap edition of David Copperfield with a frown of concentration on his forehead. Quint was not a regular reader, nor was he a swift one. To Adam’s certain knowledge, he had been reading the Dickens novel for the last four months and he had still not progressed much beyond page 200. His habit of returning to re-read again and again passages which had caught his attention was slowing him down, and Adam suspected that the one book might last his servant the rest of his life. Quint was clearly intrigued, however, by the imaginative world of The Great Inimitable. He would occasionally deliver his opinion of certain of the novel’s characters, sometimes speaking of ‘them days’ after the last time he had been looking at the book, which meant that Adam would initially be puzzled by his remarks: ‘This cove what can’t keep his ’ands on his rhino,’ Quint would say. ‘This ’ere Micawber,’ he would continue, noticing Adam’s raised eyebrow. ‘’E’s a prize duffer, ain’t ’e? What a bleedin’ juggins and no mistake. I reckon ’e got some kind of knock in ’is cradle. ’E wouldn’t know ’ow many beans make five if ’e could count ’em on ’is fingers.’

On this occasion, Quint looked up as his master entered the kitchen. ‘Working with bottles ain’t that bad, you know,’ he remarked.

‘Whoever said it was, Quint?’

‘The Copperfield bloke.’ The manservant waved the book in the air. ‘Whining on about ’ow he ’ad such a time of it when ’e was a lad, pasting labels on bottles in ’is old man’s warehouse.’

‘His stepfather’s warehouse, was it not?’

Quint shrugged. ‘Father, stepfather. Ain’t no matter. The point is I done it. Worked with bottles. And it ain’t that bad. I’ve done much worse.’

‘I don’t doubt it, Quint.’ Adam could well believe that his servant had, in the course of a chequered career, faced more unpleasant tasks than the labelling of bottles. Abandoned as a baby on the steps of the St Nicholas Hospital for Young Foundlings in Ely Place, he had been christened Quintus by the Reverend Malachi Merridew, spiritual director of the institution, who had already been presented with four other orphaned infants that week and had turned to the Latin numbering system in his search for names for them. ‘Devlin’ had come from a label on the blanket in which he had been wrapped when he had been left in Ely Place. ‘The property,’ the label had read, ‘of Devlin’s Boarding House, Ardee Street, Dublin.’

Adam had met Quint on his first foray to European Turkey. Adam had then been a gentlemanly companion to Professor Fields, much interested in the Ancient Greek past; Quint had been an ungentlemanly servant, interested mainly in drinking and brawling. However, they had formed an unexpected alliance and, on their return to London, Adam had offered Quint the position of manservant. Quint, rather to the surprise of both men, had accepted. He had accompanied his master to Athens and Macedonia once again the previous year and been a witness to the terrible crimes and strange death of Professor Fields. Now he was perched on a stool in rooms in Doughty Street, regaling Adam with his views on David Copperfield.

‘This is no time to be discussing the finer points of Dickens’s work, Quint.’ The young man took the novel from his manservant’s hands and placed it carefully on the kitchen table. ‘Nor your past history of employment. We have work to do. We have a young woman to find.’ As swiftly and concisely as he could, Adam explained the commission he had been given the previous day. He did not mention Sunman’s name, although he assumed it would have meant little to Quint had he done so.

His servant listened, chewing stolidly on a plug of tobacco.

‘I ain’t sure I’ve got this,’ he said, once Adam had finished. ‘If some cove wants to cure ’is horn by bedding a dollymop, why’s anyone worry about it?’

‘The affair is not quite as simple as you seem to think, Quint. The gentleman in question is, I suspect, in a senior position in the Foreign Office. He cannot be jumping in and out of the arms of such as Dolly Delaney without causing trouble.’

‘Even swells need a bit of fun.’

‘Yes, but their fun must be discreet fun. And, in this case, it seems it has not been.’

Quint shrugged, as if acknowledging that the ways of his betters were a mystery to him. ‘So we got to lay our ’ands on this Dolly mort?’ he asked.

‘In a manner of speaking, yes. Tomorrow you will make enquiries in the pubs around Drury Lane. Stand a drink or two. Find out if anyone knows anything about the girl.’

‘And you’ll be doing the round of the boozing-kens as well?’

‘No, I shall not.’ Adam headed towards his sitting room. ‘I shall be visiting my old friend Cosmo Jardine.’

CHAPTER THREE

Adam thought about his long friendship with Cosmo Jardine as he and Quint made their way towards Covent Garden. He and Cosmo had known one another for years, both at school and at Cambridge. Like Adam, Cosmo had left college without a degree. Adam had been forced to do so by the death of his father and the disappearance of the family fortune; his friend, much to the outrage of his own father, the dean of a West Country cathedral, had been too idle to pursue his studies and more interested in painting and sketching than in reading Homer and Cicero.

Jardine had decided he would be an artist. Settling in London with little more than the lease on part of a cheap studio in Chelsea and a letter of introduction to John Millais, Cosmo had proved himself surprisingly committed to his new profession. He had even had some small successes. Works had been accepted at the Academy, although they had been hung so high that opera glasses had been required to view them. A Yorkshire mill-owner with a taste for nude women in the kinds of classical settings that made them respectable rather than shocking had commissioned a ‘Judgement of Paris’ from him. Paintings of Cosmo’s own preferred subject matter – Arthurian legend – had been less easy to sell. A huge canvas of King Pellinore and the Questing Beast still languished in the Chelsea studio. Cosmo’s debts had mounted. Eventually, as his creditors clamoured for legal action to be taken against him, he had been forced to take up painting scenery for a theatre. Much to his own astonishment, he had discovered he enjoyed the work and now, although the need to earn money was less pressing, he continued to make his way to Drury Lane most mornings.

After saying farewell to Quint, who disappeared swiftly into a pub on Long Acre, Adam found his friend in a corner of one of the large props rooms at the back of the Prince Albert theatre.

Cosmo Jardine was standing at the edge of a huge backdrop, depicting what looked like Derby Day at Epsom, which was stretched flat across the floor. He was dressed in an ancient white frock coat, liberally speckled with paint, and was dabbing at a distant corner of the set with a long brush. He was so absorbed in his task that Adam was at his shoulder before he noticed him. ‘Hullo,’ he said in surprise. ‘What brings you to this dark corner of Drury Lane? I believe this is the first time you’ve deigned to visit me in my humble place of work.’

‘You are right,’ Adam said. ‘I have not been here before.’

‘You were once so regular a visitor to my studio that I began to think I would have to ask you for a contribution towards the rent. But, since I became an artisan toiling away in the theatre, you have deserted me.’

‘I apologize, Cosmo, I have been guilty of neglecting you.’

‘You have indeed. But I forgive you.’ The painter swung the enormous brush he was using away from the backdrop and propped it against a wooden trestle. The brush dripped red paint onto the floor. Jardine wiped his hands on his white coat as he looked at his friend more closely. ‘However, I harbour a strong suspicion that there are other reasons for your visit today beyond mere sociability.’

‘Is it so obvious?’

‘Only to one who knows you as well as I do. Come, tell me what motive you have for bearding me here in my den, beyond the mere pleasure of seeing an old friend.’

‘I’m looking for a girl who has gone missing. Her name is Dolly Delaney.’ Adam took out the cabinet card which Sunman had given him and showed it to his friend.

‘Ah, Dolly,’ Jardine said, glancing briefly at the photograph. ‘Who could forget her? I thought I hadn’t seen her for a day or two. She’s only been here a few weeks but her presence has noticeably brightened up the place.’

‘You knew her, then?’

‘Alas, not in the biblical sense. She is one of the chorus girls here.’ Cosmo looked hard at his friend. ‘But is there a reason why you are employing the past tense in speaking of her?’

‘As I say, she has disappeared. That is all.’

‘Good. I would hate to think that anything unpleasant had happened to her. She is a sweet thing. But why are you in search of her? Why are you charging around like a paladin in a medieval romance, intent on rescuing his lady?’ Jardine looked sidelong at his friend. ‘Ah, I have it. You knew her yourself.’

‘Your mind runs on such predictable tracks, Cosmo.’ Adam smiled. ‘I have never met the girl. I did not know of her existence until two days ago.’

‘So, what other reasons could there be for your interest in the fair Delaney?’ Thumb and forefinger under his chin, Jardine eyed Adam in a parody of a man engaged in deep thought. ‘I know,’ he said, snapping his fingers. ‘She is, in truth, a runaway from some landed family, fleeing her ancestral home to avoid an unwanted marriage. And her noble father, for reasons best known to himself, has employed you to seek her out and drag her back to the altar.’

Adam laughed. ‘I don’t suppose there are many daughters of the gentry employed in London’s theatres.’

‘You would be surprised. Actresses will happen even in the best-regulated families,’ Jardine said off-handedly, turning to look once more at the backdrop on the floor. His thoughts were clearly centred more on his work than the fate of the missing girl. ‘And dancers. You would be surprised by the backgrounds of one or two of Dolly’s colleagues in the chorus here. I am told that we even have a vicar’s daughter. Although that may be nothing more than rumour and calumny.’

Their conversation was interrupted by two stagehands, who passed behind Adam and his friend. A few moments later, they were staggering and grunting under the weight of a vast Chesterfield sofa, labouring noisily to move its red leather bulk out of the props room and into the corridor outside.

‘However,’ the young artist continued, watching the men disappear through the door with their burden, ‘I do not think that Dolly’s family would be found in Burke’s or Debrett’s. Or even in Crockford’s Clerical Directory. More likely to see her kinsfolk on the passenger lists of boats from Dublin to Liverpool.’

‘I’d assumed from the name that she was – is – Irish.’

‘In origins, I’m sure – Dolly herself is as Cockney as they come. To listen to her drop her aitches is an education in the language of the ordinary Londoner.’

‘But no aristocratic branches of the family.’

‘No, I think not. So that explanation of your interest cannot be correct. Perhaps she has fallen from virtue and you have been employed by one of the do-gooding societies to rescue her from the consequences of her sin?’

‘You are wrong again, Cosmo. I have not found work with a charitable organization.’

‘I am glad to hear it. Unlike the maiden ladies who run these societies, I do not believe for a moment that the majority of the tarts in London are woebegone Magdalens, forever preparing to throw themselves off Waterloo Bridge.’ Jardine now noticed the red paint, which was continuing to drip from the brush. He moved towards the trestle, picked up a rag from the floor and wound it around the head of the brush. ‘Most of them are quite happy to practise their trade, and find it advantageous to do so. They may well be better off than they would be working as maidservants or factory girls.’

‘Perhaps you are right, Cosmo. Although many must be wretched enough. But we are digressing from the subject of Dolly Delaney.’

‘I’m still in pursuit of the reason for your sudden interest in her.’

‘It is a long story, Cosmo, and not one with which I can entertain you at present.’

‘Have you no better means of employing your time, old chap?’ Jardine hoisted the brush, its head now covered with the rag, and carried it across the room. He propped it against the wall, where a dozen similar brushes stood like soldiers on parade. ‘Nothing better to do than run around town after a missing girl? She will turn up again shortly, I am sure.’

‘I am told her disappearance may be of more significance than we can imagine,’ Adam said.

‘I have often wondered why you do not take another excursion to Thessaly,’ Jardine said, ignoring his friend’s remark entirely. ‘Did you not once say that the manuscript you found in the monastery there held clues to the location of some treasure? Macedonian gold, was it not? Why not go in search of that, rather than touring London in pursuit of Dolly who, however decorative, is no more than a dancing girl. Dancing girls are ten a penny, whereas gold is a thing of beauty and a joy for ever. I would join you in looking for it myself but the climate in Greece would not suit me.’

‘The manuscript is useless, Cosmo. I thought I had said as much to you long ago. Fields had it strapped to his body. When the gun went off and shot him, it was shredded. The little that remained legible told us nothing of gold or treasure.’

‘Perhaps there is another manuscript. Gathering dust in the library of a Greek monastery.’

Adam had no chance to respond to his friend’s suggestion. From the bowels of the theatre a penetrating soprano voice suddenly erupted into life, singing an aria from Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable as if her life depended on it. ‘Who in the devil’s name is that?’ he asked, looking at Jardine in astonishment as the singer’s high notes continued to echo around the props room.

The painter had moved away from the row of giant brushes, wandering over to his backdrop and dropping to his haunches. He was staring intently at the bottom left corner. ‘That will be Letitia von Trunckel,’ he said over his shoulder. ‘Tizzi to her friends – of whom there are few. She entertains audiences here on Wednesday nights and Saturday matinees with her renditions of the classical repertoire.’

‘A powerful voice,’ Adam said.

‘Not so much bel canto as “can belto”, you might say.’

‘If you were a Punch hack in desperate search of a pun, you might.’

‘There are worse occupations than writing for Punch.’ Jardine rose to his feet. ‘I have even thought of trying my own hand at comic verse sometime.’

‘Perhaps you could set them to music and persuade Fräulein von Trunckel to sing them in the music halls. I am sure they would be a great success.’

‘Oh, never in the halls,’ Jardine said in mock disgust. ‘What do you find in most of them? Dull songs. Jokes so old they have grey whiskers. Stale sentiment. The only pleasure is to be found in admiring the ladies on promenade.’

‘Is that not the case at most places of entertainment? Is it not true of this theatre?’

‘You are correct, of course, my dear chap. Half of our evening’s entertainment here is nothing more than a leg drama. The audience, or certainly the male portion of it, comes to see the girls in the chorus dancing, not to hear the thespians prating. And Tizzi’s charms lie as much in her embonpoint as in her vocal cords.’ Jardine sighed ostentatiously. ‘No one, but no one, comes to admire the splendour of the painted backdrops. My talents are wasted here. And I an artist whose works have graced the Academy walls.’

‘Oh, what Philistines people are,’ Adam said, smiling. In truth, he knew, his friend was a sociable creature and happier here amidst the hustle and bustle of the theatre than he had ever been in his isolated Chelsea studio. ‘But I ask you again about Miss Dolly Delaney.’

In the distance, the very loud sounds of Letitia von Trunckel rehearsing had ceased and been replaced by the quieter ones of a pianist, slowly picking out the tune of a Chopin valse.

‘You are persistent, Adam, if nothing else. The person to whom you need to speak is McIlwraith.’

‘The manager of the theatre?’

‘He has a more enviable responsibility – he is the man in charge of the dancers.’ Jardine paused as the Chesterfield sofa, last seen exiting the door, came back into view and, borne by the two sweating mechanics, made its way across the props room again. ‘Although, taking his cue from his dour and doubtless puritanical Scottish ancestors, he shows little signs of admiring the female form divine. Doubtless that is why he was selected for the job.’

‘This man McIlwraith is here now? Perhaps I could speak to him?’

‘There is no show tonight. I doubt he will be in the theatre. But he will be here tomorrow.’ Jardine examined his watch, which he was carrying loose in a pocket of his paint-bespattered white coat. ‘It is approaching five,’ he said. ‘I have laboured long enough for one day. It is time to divest myself of this coat of many colours and lay down my brushes. I shall be dining at Verrey’s tonight, Adam. Perhaps you would care to join me?’

‘I cannot this evening, Cosmo. Another time.’

‘You are becoming a recluse, my friend. Skulking in your Doughty Street garret, eating bread and cheese and drinking cheap ale.’

Adam laughed. ‘Nonsense,’ he said. ‘I dine at the Marco Polo at least twice in the week. Not all of us can afford the extravagance of Verrey’s.’

‘Of course, a man can dine at his club more cheaply than elsewhere,’ Jardine conceded. ‘In truth, I cannot afford Verrey’s myself, but I allow my creditors to worry about the expense.’

‘I promise you that we shall both dine there before too long. I shall begin to put aside monies for the occasion immediately.’

‘I shall hold you to your promise. Meanwhile, I shall speak to McIlwraith and tell him to expect a visit from you soon. Tomorrow?’ Adam nodded. ‘I am sure he will be able to shed some light on the mystery surrounding the lovely Dolly’s whereabouts.’

* * * * *

The following morning found Adam once more at the theatre where Dolly had been working. Quint had again been despatched to the pubs of the neighbourhood to find out what he could. He had not seemed reluctant to go.

As Adam climbed the few stone steps to the Prince Albert’s entrance, he could not help but notice, hanging on either side of the main doors, immense placards, which advertised in glowing colours the thrills and delights to be experienced inside. One depicted Letitia von Trunckel in the famous mad scene from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor – dishevelled and enormous, the soprano was shown wandering through a baronial hall in her wedding dress. Adam wondered briefly if Cosmo had created the poster but decided it looked too crude to be his friend’s work.

Adam pushed open the door of the theatre and looked about him. There was no one in sight. The foyer was large and marble-floored. A wood-panelled box office stood to the right. It had not yet opened. The theatre, Adam thought, had the strange, slightly eerie atmosphere that all such establishments have when they are not in use. He moved forward, his shoes clicking on the hard floor.

A figure emerged from behind a green velvet curtain and hurried towards him. Adam was about to speak to him but the man, raising his hat briefly, was past and out into the street before he could question him. Adam approached the curtain and pulled it aside. A dark corridor led into the bowels of the theatre and he followed it. About twenty yards along the corridor, a gas light attached to the wall was giving off a dim light. A small boy in a crumpled red jacket and black trousers was standing beneath the light. He had a mouth organ pressed to his lips and he tootled a half-tune on it before staring malevolently at Adam.

‘You lookin’ for someone, mister?’

‘Mr McIlwraith.’

‘We ain’t open, you know. ’E’ll be rehearsing the tarts.’

Adam peered further along the gloomy corridor. Was there nobody here apart from this oddly menacing urchin? ‘I appreciate that the theatre does not open for some hours, but Mr McIlwraith is expecting me.’

The boy sniffed noisily as if to suggest that he doubted the truth of what he was being told and continued to gaze unblinkingly at Adam. A good ten seconds passed and Adam was about to speak again when the child jerked his thumb over his shoulder. ‘Big room down there,’ he said. ‘Second door on the right.’

Adam nodded his thanks and walked past the boy, who scowled at him as he did so. When the young man reached the door that had been indicated, he turned and looked back. The urchin was still there, leaning against the wall. He saw Adam watching him and stuck out his tongue.

Adam pushed open the door and went into the rehearsal room. It was flooded with light from a row of high windows. After the gloom of the corridor, the contrast was blinding and he was forced to shield his eyes briefly with his hand. When he was able to focus properly, he could see that this room, in contrast to the rest of the Prince Albert, was a hive of activity. A dozen young women stood in a row, holding a bar that ran along one wall, and swinging their left legs in the air. A man was watching them intently.

As Adam walked towards the centre of the room, several of the dancers noticed him and ceased their exercises. The man with them looked over his shoulder and saw that they had a visitor. ‘Carry on, girls,’ he shouted, and crossed to where Adam was standing, trying not to stare too closely at the legs on display.

‘You must be Mr Carver,’ the man said.

Adam acknowledged that he was.

‘McIlwraith, sir. Hamish McIlwraith. Delighted to meet you, Mr Carver.’ He shook Adam’s hand energetically. ‘Any friend of Mr Jardine’s is a friend of mine. Surprised you could find us, tucked away as we are.’

Adam explained about the small boy who had directed him.

‘Ah, Billy Bantam. He ain’t no child, sir. Older than the devil he is, I sometimes think, and twice as wicked. He’s a dwarf, Mr Carver, a performing dwarf. Been on the stage since Macready’s day. Don’t you go getting the wrong side of Billy, Mr Carver. He’s a bad’un when he wants to be.’

Adam said he would be wary of the little man if he saw him again and Mr McIlwraith beamed with delight, as if Adam had promised him a rare and costly present. The dancing master bore little resemblance to the caricature of the dour Scotsman Cosmo had painted. He was, in fact, short and plump and markedly jolly. He was also perspiring freely. He smiled amiably at Adam from a brick-red face and reached out to pump his hand again with great energy. He did not sound any more Scottish than he looked. To judge from his voice, he hailed from the city in which he worked. ‘Mr Jardine tells me as ’ow you might be interested in our Dolly.’

‘I would welcome the opportunity to speak with the young woman, certainly.’

‘Ah, there’s plenty of men interested in Dolly.’ McIlwraith winked ostentatiously. ‘There’s a gentleman by the name of Mr Wyndham, for instance. He was round the stage door for weeks asking after ’er.’

‘Wyndham?’

‘He’s what the Frenchies call a bow idle, Mr Wyndham is,’ McIlwraith went on. ‘Very handsome man. All the girls was most impressed. But it was Dolly as began to walk out with him.’

‘Might Miss Delaney be with this gentleman now?’

‘She might be.’ McIlwraith took a white handkerchief from his waistcoast pocket and mopped his brow. ‘She might not be.’ He tucked the handkerchief back into his waistcoast and continued to grin broadly at Adam.

‘But I am correct in thinking that she has not been here at work for some days—?’ the young man said.

The dancing master’s face became suddenly serious. ‘She’s a delicate flower, Dolly is,’ he said. ‘She come to me last week. “Mac,” she sez – they all call me “Mac”, the girls – “Mac”, she sez, “I’m feeling all of a flutter. I ain’t at all well.” “Dolly,” I sez, “you’re as thin as a rasher of wind, and as pale as a candle. You don’t look the ticket at all. You’d best get yourself off home.” So, no, she ain’t been at work of late.’

‘But you have no reason to be concerned for her? Beyond the fact that she was unwell?’

McIlwraith looked puzzled.

‘She has not been seen at her lodgings in the last week,’ Adam explained.

The dancing master puckered his lips and blew out a breath of air. He stared at the floor as if the answer to the question of Dolly’s whereabouts might be written on its wooden boards. ‘Maybe she has been with young Wyndham,’ he said eventually.

One of the dancers, a tall girl with dark curls and a willowy figure, had detached herself from the group practising their steps and moved across the room. She was now standing behind McIlwraith and listening to the conversation. ‘You ain’t goin’ to find Dolly with that time-waster Wyndham,’ she said. ‘Whatever ’e sez.’ She jerked her thumb contemptuously at the dancing master.

‘Get off with you, Hetty,’ McIlwraith said, turning around and seeing her for the first time. He now seemed much less jolly. In fact, he looked close to furious. ‘The gentleman don’t want to be bothered with your nonsense.’

‘Dolly wasn’t interested in a little mama’s boy.’

‘As I said before, Mr Carver, Mr Wyndham is a very ’andsome man.’ McIlwraith, doing his very best to ignore the girl, returned his attention to Adam. ‘Much like your good self, if I may be so bold.’ The dancing master aimed an ingratiating smile in Adam’s direction.

‘’Andsome is as ’andsome does,’ Hetty said. ‘And what Wyndham does is try to get his fingers in your frills. The girls knows all about ’im and the likes of ’im. No money, but all over you like an octerpus. And ’e ain’t that much of a looker, anyways. Dolly wouldn’t go with him.’

‘You’d do best to keep your mouth shut, my girl,’ McIlwraith snapped, rounding on her again.

‘Do you know where Miss Delaney is now?’ Adam addressed his remark to the girl. She shook her head. ‘So, for all you know, she might be with this gentleman named Wyndham?’

‘I tell you, she ain’t with ’im.’ The girl looked Adam in the eye, ignoring the dancing master, who was fussing and fretting at her side.

Adam would have welcomed the chance to speak further with Hetty but he felt constrained by McIlwraith’s presence. He said no more.

‘Well, if you ain’t interested, you ain’t interested,’ the girl said after a pause, and flounced off to join the other dancers.

Adam watched her go. He would have to talk to her again when she was alone. He turned once more to resume his conversation with McIlwraith, who seemed to have recovered his good humour.

‘Hetty’s a lively one,’ the dancing master said, with what looked very much like a wink. ‘Always jumping around like a pea on a griddle. I wouldn’t take too much notice of what she says, if I was you.’

‘Well, perhaps I could speak to this gentleman named Wyndham. Do you have an address for him?’

McIlwraith waved his arm vaguely in the direction of the door leading to the outer corridor, as if he suspected that Wyndham might be lurking there. ‘He lodges somewhere north of the Park, I believe. Tyburnia. A coming area, I’ve heard.’

‘But you do not know exactly where.’

The dancing master shook his head.

‘Well, perhaps I could write Miss Delaney a note and leave it here with you,’ Adam said. ‘I would like very much to speak to her and know that she is safe and well.’

‘Lord, Mr Carver, you might just as well send a letter to a milestone on the Dover road.’ The man could scarcely contain his amusement, wheezing with the effort of attempting to do so. ‘Dolly can’t read letters, sir. Not even what the Frenchies call billy deuces. She can’t read anything at all.’

* * * * *

Adam stood in the marble-floored foyer of the Prince Albert and wondered where he should go next. The theatre was no longer eerily deserted. The box office was open, and people were coming and going through the heavy swing doors that led out to Drury Lane. The young man watched them for a while as he considered whether he had learned anything of interest. McIlwraith had seemed eager to point his finger at the man Wyndham as a possible beau for Dolly; the dancer Hetty had been equally adamant that her friend would have had nothing to do with him. He would have to speak to Hetty again when McIlwraith was not present. As he pondered the matter, he noticed a familiar figure enter the theatre. It was Cosmo Jardine.

‘Ah, the very man,’ the painter said as he saw his friend. ‘I thought perhaps you would be here. How was our Caledonian dancing master? Was he able to enlighten you as to the whereabouts of the fair Delaney?’

Adam shook his head. ‘All he knows is that he sent her home last week because she was feeling unwell. He has not seen her since. But I have also been told that Dolly has not been at her lodgings these last few days.’

The painter took his friend by the arm and guided him to the street. ‘Let us take a stroll towards Long Acre,’ he said, pointing down Drury Lane with a flourish. ‘I have news for you myself.’

The two young men ambled arm-in-arm through the city crowds. Adam waited to hear what his friend’s news was but Jardine seemed in no hurry to impart it. Instead, he launched himself into a denunciation of the Prince Albert’s manager. ‘The man is impossible. No sooner have I finished my Herculean labours on a dozen flats for the next production than he asks, nay, demands, that I should create another for a scene he has inserted at the last minute. I wouldn’t mind, but it is only what we call a carpenter scene.’

‘Which is . . .?’

‘One which exists solely so that the carpenters and stagehands can put up the sets for the next act. Why does he need an artist for such work? Any Tom, Dick or Harry could do it.’

Jardine was full of mock indignation but Adam was not listening to him very closely. ‘I don’t suppose you know a chap named Wyndham, do you?’ he asked, as the painter paused briefly to take breath.

Jardine looked puzzled.

‘Some stage-door Lothario who pesters the girls,’ his friend went on. ‘Who pestered Dolly.’

‘Ah, that Wyndham.’ The artist took a step to one side to allow a smartly dressed woman with a pug dog on a lead to pass him. ‘I thought for one horrid moment you meant Ben Wyndham of Lincoln’s Inn.’

‘And who might Ben Wyndham be?’

‘A lawyer to whom I owe a trifling sum. I have no desire to talk of him.’

‘What of this other Wyndham?’

‘What is there to say? Perfectly ordinary fellow. Comes from a highly respectable Berkshire family.’

‘This highly respectable family in Berkshire—?’

‘Place near Newbury, I believe.’

‘This highly respectable family with a place near Newbury. Would they be delighted to hear of their son and heir making eyes at a Drury Lane dancer?’

‘Probably not. As I say, far too respectable.’

‘Might they pay the Drury Lane dancer to vanish from the scene?’

‘It is possible, I suppose,’ Jardine said slowly. ‘But it is not very likely, is it? And why should Dolly accept the money? She would see more long-term advantage in keeping her talons firmly in the flesh of young Wyndham – that is, always assuming that she wished to marry into respectability. Truth to tell, Dolly never seemed to me the mercenary kind. Her friend Hetty perhaps, but not Dolly. No, I think you are barking up the wrong tree there, old man.’

‘I have met Hetty.’

‘Quite the harpy, is she not?’

‘She seemed a young lady of strong opinions, certainly.’

‘Has she no notion where her friend has gone?’

‘I had little chance to speak to her. I shall question her again when McIlwraith is not with her.’

‘It may not be necessary. After you left yesterday, I made my own enquiries about the absent Dolly.’

‘That was kind of you, Cosmo.’ Adam was surprised. It was unusual for his friend to go much out of his way to assist others.

‘No trouble, my dear chap,’ the painter said airily, as they made their way into Long Acre. ‘Always happy to oblige if I can.’

‘Did your enquiries prove fruitful?’