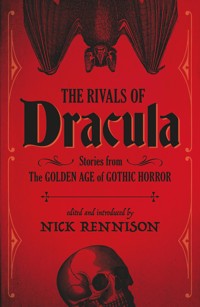

6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

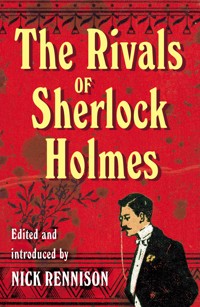

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Bram Stoker's Dracula, still the most famous of all vampire stories, was first published in 1897. But the bloodsucking Count was not the only member of the undead to bare his fangs in the literature of the period. Late Victorian and Edwardian fiction is full of vampires and this anthology of scary stories introduces modern readers to fifteen of them. A travel writer in Sweden unleashes something awful from an ancient mausoleum. A psychic detective battles a vampire that has taken refuge in an Egyptian mummy. A nightmare becomes reality in the tower room of a gloomy country house. The Rivals of Dracula is a collection of classic tales to chill the blood and tingle the spine, including the following stories: Alice & Claude Askew - 'Aylmer Vance and the Vampire' EF Benson - 'The Room in the Tower' Mary Cholmondeley - 'Let Loose' Ulric Daubeny - 'The Sumach' Augustus Hare - 'The Vampire of Croglin Grange' Julian Hawthorne - 'Ken's Mystery' E and H Heron - 'The Story of Baelbrow' MR James - 'Count Magnus' Vernon Lee - 'Marsyas in Flanders' Richard Marsh - 'The Mask' Hume Nisbet - 'The Vampire Maid' Frank Norris - 'Grettir at Thorhall-stead' Phil Robinson - 'Medusa' HB Marriott Watson - 'The Stone Chamber'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE RIVALS OF DRACULA

Bram Stoker’sDracula, still the most famous of all vampire stories, was first published in 1897. But the bloodsucking Count was not the only member of the undead to bare his fangs in the literature of the period. Late Victorian and Edwardian fiction is full of vampires and this anthology of scary stories introduces modern readers to fifteen of them. A travel writer in Sweden unleashes something awful from an ancient mausoleum. A psychic detective battles a vampire that has taken refuge in an Egyptian mummy. A nightmare becomes reality in the tower room of a gloomy country house. Including works by both well-known writers of the supernatural such as MR James and EF Benson and less familiar authors like the Australian Hume Nisbet and the American F Marion Crawford,The Rivals of Draculais a collection of classic tales to chill the blood and tingle the spine.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nick Rennison is a writer, editor and bookseller. He has published books on a wide variety of subjects from Sherlock Holmes to London’s blue plaques. He is a regular reviewer for the Sunday Times and for BBC History magazine. His titles for Pocket Essentials includeSigmund Freud,Peter MarkRoget: The Man Who Became a Book,Robin Hood: Myth, History & CultureandA Short History of Polar Exploration. He lives near Manchester.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I would like to thank Ion Mills, Claire Watts, Frances Teehan, Clare Quinlivan and everybody at Oldcastle Books for their hard work and help as I was compiling this anthology. Thanks too to Elsa Mathern for the excellent cover design and to Jayne Lewis and Irene Goodacre for the copy-editing and proof-reading skills which enabled them to pick up many mistakes which would have otherwise gone uncorrected. However, my greatest thanks, as always, go to my wife Eve who is an ever-present source of love and encouragement.

Introduction

In 1897, the Irish author Bram Stoker published a novel which has become the most famous of all vampire stories. The novel was, of course, Dracula. It is almost needless to note that Stoker did not invent the figure of the vampire. Indeed, belief in creatures which return from the grave to prey upon their living victims or which suck the blood and the life from human beings seems to have existed for millennia. The Edimmu in Sumerian mythology, the Strix in Ancient Greece and Rome, the Vetala in Hindu mythology all have attributes that link them to the vampire. Fast forward to Europe in the Middle Ages and there are plenty of stories of vampire-like creatures from England to Hungary. They continued to be recorded for several centuries and, even in the supposedly enlightened eighteenth century, reports of real-life vampires flooded out of Eastern Europe. The idea of vampirism seems to have been particularly strong in Slavic folklore and it was in Transylvania that Stoker chose to place the homeland of his own vampire.

The name ‘Dracula’ he took from a historical figure, Vlad III, Prince of Wallachia, born in 1431. Vlad’s father had been given the honorary name of ‘Dracul’ (the Wallachian word for ‘dragon’) and Vlad was described as ‘Dracula’ or ‘son of the dragon’. Schooled in the brutal politics of Eastern Europe in the mediaeval era, Vlad Dracula was renowned for the bloodthirsty punishments he inflicted on his enemies. During several spells as ruler, which finally ended with his death in battle in 1476, he gained the nickname Vlad the Impaler because of his fondness for impaling those who opposed him on wooden stakes and leaving their bodies to terrorise any others who might think of taking up arms against him. One chronicler reports seeing twenty thousand men, women and children who had suffered this punishment. After his death, Vlad Dracula rapidly became a byword for cruelty and books describing his misdeeds with alluring titles like The Frightening and Truly Extraordinary Story of a Wicked Blood-drinking Tyrant Called Prince Dracula were published in the Balkans and further afield. Some scholars claim that Vlad Dracula has been unjustly stigmatised. His cruelties were no worse than those of many other mediaeval rulers whose reputations have not suffered as his has done. In Romania he is seen as a significant figure in the nation’s history who built a strong and independent state of Wallachia and defended it against the Turks. In the rest of the world he is fated to be remembered because, one day in the 1890s, Bram Stoker read of him in a history of Eastern Europe and decided to borrow his name for the vampiric anti-hero of a novel he was writing.

Stoker did not invent the vampire and nor was he the first writer to make use of the creature in his work. The literary vampire first makes an appearance in eighteenth-century poetry, originally in Germany and, towards the end of the century, in England. An obscure German poet, Heinrich August Ossenfelder, published ‘Der Vampir’ in 1748, a short poem which reflected interest at the time in a series of reports from Eastern Europe and the Balkans of vampire activity in the Austrian Empire. Ossenfelder seems to have introduced the vampire into European literature and other German poets, most notably Goethe in ‘The Bride of Corinth’, followed his example. In England, a vampire is a peripheral character in Robert Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer and Coleridge’s unfinished Christabel can be interpreted as a vampire romance.

Romantic poets also had a role to play in the appearance of the vampire in prose fiction. In the summer of 1816, Byron and Shelley, together with Shelley’s soon-to-be wife Mary, were staying at the Villa Diodati in the Swiss village of Cologny. Conversation turned frequently to the supernatural and all three began to write stories on the subject. The only one that was finished was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. However, Byron did produce a fragment of a novel, which found its way into print (against the poet’s wishes) in 1819. What was published does suggest that Byron intended to write a vampire story and his personal physician John Polidori, who was also present at the Villa Diodati, took inspiration from what little had been written. Polidori created his own supernatural tale which was published as The Vampyre in the same year. Confusingly, it first appeared under Byron’s name, presumably in order to increase its commercial appeal, but Polidori soon laid claim to it and his authorship was acknowledged in later editions.

Polidori followed romantic tradition by dying young in 1821 at the age of only twenty-five but his book lived on. In the words of Christopher Frayling, in an introduction to a 1990s anthology of vampire literature, his novella is ‘the first story successfully to fuse the disparate elements of vampirism into a coherent literary genre’. It was popular enough to be plagiarised in copycat stories, adapted into plays and even set to music. Heinrich Marschner’s Der Vampyr of 1828 took one of the dramas cobbled together from Polidori’s work and transformed it into an opera which is still occasionally performed today. Over the next decade and a half there were one or two noteworthy examples of vampire literature (the 1841 Russian novella Oupyr by Alexei Tolstoy, a distant cousin of the more famous Leo, is an interesting curiosity) but the most significant development came in the mid-1840s.

At the time, a new audience for cheap, sensationalist reading matter was developing and the so-called ‘penny dreadful’ had emerged to cater for it. One of the most successful of the penny dreadful serials, first published between 1845 and 1847 and eventually running to more than half a million words, was Varney the Vampire. Most probably written by a prolific hack author named James Malcolm Rymer (who may also have had a hand in the first story to feature the demon barber Sweeney Todd) this was what a recent writer has described as ‘a rambling gore-fest’ in which the vampire Sir Francis Varney regularly indulges his lust for human blood. Actually sub-titled ‘The Feast of Blood’, Varney’s bloodsucking adventures were immensely popular with their target readership (broadly speaking, the newly literate urban working class) and introduced a number of standard ideas about fictional vampires that have survived to the present day. Varney was, for example, one of the first vampires to come equipped with fangs, the better to get at his favourite sustenance. In pursuit of one victim, he ‘seizes her neck in his fang-like teeth – a gush of blood, and a hideous sucking noise follows’.

Across Europe in the decades to follow, writers produced vampire novels. Some were as lurid as the tales of Varney; others were more subtle and sophisticated. The French novelist Paul Féval, a rival of Dumas in historical fiction, wrote a trilogy (Le ChevalierTénèbre, La Vampire and La Ville Vampire) which has been translated into English by the science fiction and horror writer Brian Stableford; in Germany the prolific travel writer and novelist Hans Wachenhusen published Der Vampyr in 1878 which is set in Bulgaria under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and features a former Orthodox priest as its villain.

In English, the best-known vampire fiction by far of this period is Carmilla, a novella by Sheridan Le Fanu which was serialised in a magazine in 1871 and published in a collection of short works entitled In a Glass Darkly the following year. Born into a Huguenot family long resident in Dublin and related on his mother’s side to the playwright Sheridan, Le Fanu trained as a lawyer but soon turned to journalism and fiction. He published more than a dozen novels, including Uncle Silas and The House by the Church Yard, and became renowned for his ghost stories. Carmilla, with its tale of the unsettling relationship between the narrator Laura and the enigmatic title character, was not the first work of vampire fiction in which the main vampiric protagonist is female but it has become the most influential. On screen, it has provided the inspiration for a wide variety of works from Hammer horror films to YouTube web series. And in the two decades immediately after its publication it influenced other writers, including most notably Le Fanu’s fellow Irishman Bram Stoker. Names in the later novel echo the earlier book (Rheinfeldt in Carmilla, Renfield in Dracula); the lonely castle in Styria which is the setting for Le Fanu’s story is pushed even further east and made even more remote when it is reimagined as Dracula’s castle in Stoker’s novel; the descriptions of the vampiric women in the two tales (Carmilla in the earlier work, Lucy Westenra in the later) are similar. Ideas about repressed sexual desire, implicit in Dracula, are, bearing in mind the constraints of the Victorian era, closer to the surface in Le Fanu’s book. And, even more shockingly, the desires are lesbian.

Dracula very clearly drew on Le Fanu’s earlier book but it contains the vampire who would soon overshadow all other literary vampires. Who exactly was its creator? Abraham ‘Bram’ Stoker was born in Dublin in 1847 and originally worked as a civil servant in the city. His first published book was the less than exciting volume, TheDuties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland. In 1876, Stoker, a great theatre-lover, met the legendary Victorian actor Henry Irving and, two years later, he gave up his civil service career to become Irving’s manager at the Lyceum Theatre in London. In London, he began to publish short stories and novels, often with a supernatural theme. His most famous novel did win praise on its first publication in May 1897. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote to Stoker to say how much he had enjoyed the book calling it ‘the very best story of diablerie which I have read for many years’. The Daily Mail reviewer thought it a better book than Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Yet other reviewers at the time were dismissive. ‘It reads at times,’ one wrote, ‘like a mere series of grotesquely incredible events.’ The book was not a bestseller and, thanks to mistakes in registering its copyright, Stoker made little money from it. He continued to publish further fiction including The Jewel of Seven Stars, a story of mummies, reincarnation and ancient Egyptian curses, and The Lair of the White Worm, a tale of ancient evil that was fated to be modernised and made into a fantastically bad but curiously enjoyable film by Ken Russell in the 1980s. When Stoker died in London on 20 April 1912 he was not a rich man and Dracula had not yet become the archetypal figure of sinister power and allure which we know today. It was the twentieth-century adaptations, revisions, sequels and re-tellings of his story, most notably those on film, which were to turn the Count into legend.

So famous has Dracula become that it is all too easy to believe that he was the only fictional vampire of his day. Nothing could be further from the truth. There was something about the figure of the vampire that appealed to the imaginations of late Victorian and Edwardian readers as much as it does, in different ways, to so many people today. This anthology attempts to reflect the diversity of vampire stories that flourished in the two decades before and the two decades after the publication of Stoker’s iconic tale. The authors range from writers like EF Benson and MR James who are rightly renowned for the literary qualities of their supernatural fiction to those like the Askews, husband and wife, and the Prichards (aka the Herons), mother and son, who have been more or less forgotten. The Askews and the Prichards, like other writers such as Richard Marsh whose work features in the anthology, made their livings by producing stories for the vast number of weekly and monthly magazines that proliferated in the period. They were not literary stylists and they were often obliged to pour out fiction at such a rate that quantity became as important as quality but they aimed always to write exciting and readable narratives and they mostly succeeded. What can be termed ‘weird’ fiction was a very important part of the entertainment served up by the story magazines and the vampires took their places alongside the ghosts, ghouls and supernatural creatures of all kinds which populated their pages.

These vampires reflect a variety of turn-of-the-century anxieties and interests. Readers will notice just how many of them are voracious women who prey on initially unsuspecting men. Whether traditional vampires like Hume Nisbet’s vampire maid or homicidal maniacs like Mary Brooker in Richard Marsh’s ‘The Mask’ or psychic vampires like Mrs Tierce in Phil Robinson’s ‘Medusa’, the female of the species is often deadlier than the male. It’s not too much of an imaginative leap to link this preponderance of she-vampires with the rise of the ‘New Woman’, the self-assertive feminist of the 1880s and 1890s, and the concerns about sexuality and the relationship between the sexes that she aroused. The classic vampire story is wary of the foreign as well as the feminine. In Carmilla, the title character who threatens the English heroine Laura comes from the backwaters of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; in Dracula, emphasis is laid upon the distance from the safety of home that Jonathan Harker has travelled to reach the Count’s castle and the Count’s arrival at Whitby marks a terrible intrusion of violent otherness into the ordered society of late Victorian England.

Perhaps more than anything, however, the stories selected in The Rivals of Dracula show an awareness of the power of history. In tale after tale of the fifteen in the book, the past is not past. Like the undead Dracula it returns to trouble people in the present. Both the narrator of HB Marriott Watson’s ‘The Stone Chamber’ and his friend Warrington are frighteningly influenced by the violent events that took place nearly two centuries earlier in the room of its title. In Mary Cholmondeley’s ‘Let Loose’, the remote Yorkshire village of Wet Waste-on-the-Wolds seems trapped in the past and the evil spirit of an extinct family is accidentally released to prey once more on the villagers. MR James’s stories are permeated by his ambivalent fascination with history and ‘Count Magnus’ shows the dangers of prying too insistently into its nooks and corners.

The stories I have included in The Rivals of Dracula reveal a wide variety of vampires at work. There is an undead Icelander who fights with one of the heroes of the sagas (‘Grettir at Thorhall-stead’); there is a vampiric spirit which takes over the physical form of an ancient mummy (‘Aylmer Vance and the Vampire’); there is a murdered Italian girl who returns to feed upon the blood of the man she once loved (‘For the Blood is the Life’); there is even a tree which sucks the life from those who rest in its branches (‘The Sumach’). These rivals are, more often than not, very different from the bloodsucking Count of Stoker’s novel and very different one from another. The stories in which they appear all, however, remain well worth reading.

Aylmer Vance and the Vampire

Alice Askew (1874–1917) and Claude Askew (1865–1917)

The son of a clergyman, Claude Askew was at school at Eton and then travelled on the Continent as a young man. He married Alice Leake, the daughter of an army colonel, in 1900 and they were soon earning their living with their pens. Their first successes were with newspaper serials but they rapidly moved on to hardcover fiction. The Askews were astonishingly prolific and published nearly ninety books in a dozen years (nine novels appeared under their names in 1913 alone) but almost all of them have been forgottenand are long out of print. Their one venture into the realm of the supernatural consisted of eight stories which appeared in an obscure magazine named The Weekly Tale-Teller in 1914. These featured an intrepid psychic detective named Aylmer Vance and his Watson-like sidekick Dexter. Vance and Dexter face an assortment of supernatural beings in their adventures, including, in the one printed below, a vampire. During the First World War, both Askews travelled to Serbia to work with a field hospital attached to the Serbian army and to write about the country which was one of Britain’s allies in the war. In 1917, they both died when the Italian steamer on which they were making their way to Corfu to join Serbian soldiers in exile was torpedoed by a German submarine and sank.

Aylmer Vance had rooms in Dover Street, Piccadilly, and now that I had decided to follow in his footsteps and to accept him as my instructor in matters psychic, I found it convenient to lodge in the same house. Aylmer and I quickly became close friends, and he showed me how to develop that faculty of clairvoyance which I had possessed without being aware of it. And I may say at once that this particular faculty of mine proved of service on several important occasions.

At the same time I made myself useful to Vance in other ways, not the least of which was that of acting as recorder of his many strange adventures. For himself, he never cared much about publicity, and it was some time before I could persuade him, in the interests of science, to allow me to give any detailed account of his experiences to the world.

The incidents which I will now narrate occurred very soon after we had taken up our residence together, and while I was still, so to speak, a novice.

It was about ten o’clock in the morning that a visitor was announced. He sent up a card which bore upon it the name of Paul Davenant.

The name was familiar to me, and I wondered if this could be the same Mr Davenant who was so well known for his polo playing and for his success as an amateur rider, especially over the hurdles? He was a young man of wealth and position, and I recollected that he had married, about a year ago, a girl who was reckoned the greatest beauty of the season. All the illustrated papers had given their portraits at the time, and I remember thinking what a remarkably handsome couple they made.

Mr Davenant was ushered in, and at first I was uncertain as to whether this could be the individual whom I had in mind, so wan and pale and ill did he appear. A finely built, upstanding man at the time of his marriage, he had now acquired a languid droop of the shoulders and a shuffling gait, while his face, especially about the lips, was bloodless to an alarming degree.

And yet it was the same man, for behind all this I could recognise the shadow of the good looks that had once distinguished Paul Davenant.

He took the chair which Aylmer offered him – after the usual preliminary civilities had been exchanged – and then glanced doubtfully in my direction. ‘I wish to consult you privately, Mr Vance,’ he said. ‘The matter is of considerable importance to myself, and, if I may say so, of a somewhat delicate nature.’

Of course I rose immediately to withdraw from the room, but Vance laid his hand upon my arm.

‘If the matter is connected with research in my particular line, Mr Davenant,’ he said, ‘if there is any investigation you wish me to take up on your behalf, I shall be glad if you will include Mr Dexter in your confidence. Mr Dexter assists me in my work. But, of course…’

‘Oh, no,’ interrupted the other, ‘if that is the case, pray let Mr Dexter remain. I think,’ he added, glancing at me with a friendly smile, ‘that you are an Oxford man, are you not, Mr Dexter? It was before my time, but I have heard of your name in connection with the river. You rowed at Henley, unless I am very much mistaken.’

I admitted the fact, with a pleasurable sensation of pride. I was very keen upon rowing in those days, and a man’s prowess at school and college always remain dear to his heart. After this we quickly became on friendly terms, and Paul Davenant proceeded to take Aylmer and myself into his confidence.

He began by calling attention to his personal appearance. ‘You would hardly recognise me for the same man I was a year ago,’ he said. ‘I’ve been losing flesh steadily for the last six months. I came up from Scotland about a week ago, to consult a London doctor. I’ve seen two – in fact, they’ve held a sort of consultation over me – but the result, I may say, is far from satisfactory. They don’t seem to know what is really the matter with me.’

‘Anaemia – heart,’ suggested Vance. He was scrutinising his visitor keenly, and yet without any particular appearance of doing so. ‘I believe it not infrequently happens that you athletes overdo yourselves – put too much strain upon the heart…’

‘My heart is quite sound,’ responded Davenant. ‘Physically it is in perfect condition. The trouble seems to be that it hasn’t enough blood to pump into my veins. The doctors wanted to know if I had met with an accident involving a great loss of blood – but I haven’t. I’ve had no accident at all, and as for anaemia, well, I don’t seem to show the ordinary symptoms of it. The inexplicable thing is that I’ve lost blood without knowing it, and apparently this has been going on for some time, for I have been getting steadily worse. It was almost imperceptible at first – not a sudden collapse, you understand, but a gradual failure of health.’

‘I wonder,’ remarked Vance slowly, ‘what induced you to consult me? For you know, of course, the direction in which I pursue my investigations. May I ask if you have reason to consider that your state of health is due to some cause which we may describe as super-physical?’

A slight colour came to Davenant’s white cheeks.

‘There are curious circumstances,’ he said in a low and earnest tone of voice. ‘I’ve been turning them over in my mind, trying to see light through them. I daresay it’s all the sheerest folly – and I must tell you that I’m not in the least a superstitious sort of man. I don’t mean to say that I’m absolutely incredulous, but I’ve never given thought to such things – I’ve led too active a life. But, as I have said, there are curious circumstances about my case, and that is why I decided upon consulting you.’

‘Will you tell me everything without reserve?’ said Vance. I could see that he was interested.

He was sitting up in his chair, his feet supported on a stool, his elbows on his knees, his chin in his hands – a favourite attitude of his. ‘Have you,’ he suggested, slowly, ‘any mark upon your body, anything that you might associate, however remotely, with your present weakness and ill-health?’

‘It’s a curious thing that you should ask me that question,’ returned Davenant, ‘because I have got a curious mark, a sort of scar, that I can’t account for. But I showed it to the doctors, and they assured me that it could have nothing whatever to do with my condition. In any case, if it had, it was something altogether outside their experience. I think they imagined it to be nothing more than a birthmark, a sort of mole, for they asked me if I’d had it all my life. But that I can swear I haven’t. I only noticed it for the first time about six months ago, when my health began to fail. But you can see for yourself.’

He loosened his collar and bared his throat. Vance rose and made a careful scrutiny of the suspicious mark. It was situated a very little to the left of the central line, just above the clavicle, and, as Vance pointed out, directly over the big vessels of the throat. My friend called to me so that I might examine it, too. Whatever the opinion of the doctors may have been, Aylmer was obviously deeply interested. And yet there was very little to show. The skin was quite intact, and there was no sign of inflammation. There were two red marks, about an inch apart, each of which was inclined to be crescent in shape. They were more visible than they might otherwise have been owing to the peculiar whiteness of Davenant’s skin.

‘It can’t be anything of importance,’ said Davenant, with a slightly uneasy laugh. ‘I’m inclined to think the marks are dying away.’

‘Have you ever noticed them more inflamed than they are at present?’ inquired Vance. ‘If so, was it at any special time?’

Davenant reflected. ‘Yes,’ he replied slowly, ‘there have been times, usually, I think perhaps invariably, when I wake up in the morning, that I’ve noticed them larger and more angry looking. And I’ve felt a slight sensation of pain – a tingling – oh, very slight, and I’ve never worried about it. Only now you suggest it to my mind, I believe that those same mornings I have felt particularly tired and done up – a sensation of lassitude absolutely unusual to me. And once, Mr Vance, I remember quite distinctly that there was a stain of blood close to the mark. I didn’t think anything of it at the time, and just wiped it away.’

‘I see.’ Aylmer Vance resumed his seat and invited his visitor to do the same. ‘And now,’ he resumed, ‘you said, Mr Davenant, that there are certain peculiar circumstances you wish to acquaint me with. Will you do so?’

And so Davenant readjusted his collar and proceeded to tell his story. I will tell it as far as I can, without any reference to the occasional interruptions of Vance and myself.

Paul Davenant, as I have said, was a man of wealth and position, and so, in every sense of the word, he was a suitable husband for Miss Jessica MacThane, the young lady who eventually became his wife. Before coming to the incidents attending his loss of health, he had a great deal to recount about Miss MacThane and her family history.

She was of Scottish descent, and although she had certain characteristic features of her race, she was not really Scotch in appearance. Hers was the beauty of the far South rather than that of the Highlands from which she had her origin. Names are not always suited to their owners, and Miss MacThane’s was peculiarly inappropriate. She had, in fact, been christened Jessica in a sort of pathetic effort to counteract her obvious departure from normal type. There was a reason for this which we were soon to learn.

Miss MacThane was especially remarkable for her wonderful red hair, hair such as one hardly ever sees outside of Italy – not the Celtic red – and it was so long that it reached to her feet, and it had an extraordinary gloss upon it so that it seemed almost to have individual life of its own.

Then she had just the complexion that one would expect with such hair, the purest ivory white, and not in the least marred by freckles, as is so often the case with red-haired girls. Her beauty was derived from an ancestress who had been brought to Scotland from some foreign shore – no one knew exactly whence.

Davenant fell in love with her almost at once and he had every reason to believe, in spite of her many admirers, that his love was returned. At this time he knew very little about her personal history. He was aware only that she was very wealthy in her own right, an orphan, and the last representative of a race that had once been famous in the annals of history – or rather infamous, for the MacThanes had distinguished themselves more by cruelty and lust of blood than by deeds of chivalry. A clan of turbulent robbers in the past, they had helped to add many a blood-stained page to the history of their country.

Jessica had lived with her father, who owned a house in London, until his death when she was about fifteen years of age. Her mother had died in Scotland when Jessica was still a tiny child. Mr MacThane had been so affected by his wife’s death that, with his little daughter, he had abandoned his Scotch estate altogether – or so it was believed – leaving it to the management of a bailiff – though, indeed, there was but little work for the bailiff to do, since there were practically no tenants left. Blackwick Castle had borne for many years a most unenviable reputation.

After the death of her father, Miss MacThane had gone to live with a certain Mrs Meredith, who was a connection of her mother’s – on her father’s side she had not a single relation left.

Jessica was absolutely the last of a clan once so extensive that intermarriage had been a tradition of the family, but for which the last two hundred years had been gradually dwindling to extinction.

Mrs Meredith took Jessica into Society – which would never have been her privilege had Mr MacThane lived, for he was a moody, self-absorbed man, and prematurely old – one who seemed worn down by the weight of a great grief.

Well, I have said that Paul Davenant quickly fell in love with Jessica, and it was not long before he proposed for her hand. To his great surprise, for he had good reason to believe that she cared for him, he met with a refusal; nor would she give any explanation, though she burst into a flood of pitiful tears.

Bewildered and bitterly disappointed, he consulted Mrs Meredith, with whom he happened to be on friendly terms, and from her he learnt that Jessica had already had several proposals, all from quite desirable men, but that one after another had been rejected.

Paul consoled himself with the reflection that perhaps Jessica did not love them, whereas he was quite sure that she cared for himself. Under these circumstances he determined to try again.

He did so, and with better result. Jessica admitted her love, but at the same time she repeated that she would not marry him. Love and marriage were not for her. Then, to his utter amazement, she declared that she had been born under a curse – a curse which, sooner or later was bound to show itself in her, and which, moreover, must react cruelly, perhaps fatally, upon anyone with whom she linked her life. How could she allow a man she loved to take such a risk? Above all, since the evil was hereditary, there was one point upon which she had quite made up her mind: no child should ever call her mother – she must be the last of her race indeed.

Of course, Davenant was amazed and inclined to think that Jessica had got some absurd idea into her head which a little reasoning on his part would dispel. There was only one other possible explanation. Was it lunacy she was afraid of? But Jessica shook her head. She did not know of any lunacy in her family. The ill was deeper, more subtle than that. And then she told him all that she knew.

The curse – she made use of that word for want of a better – was attached to the ancient race from which she had her origin. Her father had suffered from it, and his father and grandfather before him. All three had taken to themselves young wives who had died mysteriously, of some wasting disease, within a few years. Had they observed the ancient family tradition of intermarriage this might possibly not have happened, but in their case, since the family was so near extinction, this had not been possible.

For the curse – or whatever it was – did not kill those who bore the name of MacThane. It only rendered them a danger to others. It was as if they absorbed from the blood-soaked walls of their fatal castle a deadly taint which reacted terribly upon those with whom they were brought into contact, especially their nearest and dearest.

‘Do you know what my father said we have it in us to become?’ said Jessica with a shudder.

‘He used the word vampires. Paul, think of it – vampires – preying upon the life blood of others.’ And then, when Davenant was inclined to laugh, she checked him. ‘No,’ she cried out, ‘it is not impossible. Think. We are a decadent race. From the earliest times our history has been marked by bloodshed and cruelty. The walls of Blackwick Castle are impregnated with evil – every stone could tell its tale, of violence, pain, lust, and murder. What can one expect of those who have spent their lifetime between its walls?’

‘But you have not done so,’ exclaimed Paul. ‘You have been spared that, Jessica. You were taken away after your mother died, and you have no recollection of Blackwick Castle, none at all. And you need never set foot in it again.’

‘I’m afraid the evil is in my blood,’ she replied sadly, ‘although I am unconscious of it now. And as for not returning to Blackwick – I’m not sure I can help myself. At least, that is what my father warned me of. He said there is something there, some compelling force that will call me to it in spite of myself. But, oh, I don’t know – I don’t know, and that is what makes it so difficult. If I could only believe that all this is nothing but an idle superstition, I might be happy again, for I have it in me to enjoy life, and I’m young, very young, but my father told me these things when he was on his deathbed.’ She added the last words in a low, awe-stricken tone.

Paul pressed her to tell him all that she knew, and eventually she revealed another fragment of family history which seemed to have some bearing upon the case. It dealt with her own astonishing likeness to that ancestress of a couple of hundred years ago, whose existence seemed to have presaged the gradual downfall of the clan of the MacThanes.

A certain Robert MacThane, departing from the traditions of his family, which demanded that he should not marry outside his clan, brought home a wife from foreign shores, a woman of wonderful beauty, who was possessed of glowing masses of red hair and a complexion of ivory whiteness – such as had more or less distinguished since then every female of the race born in the direct line.

It was not long before this woman came to be regarded in the neighbourhood as a witch. Queer stories were circulated abroad as to her doings, and the reputation of Blackwick Castle became worse than ever before.

And then one day she disappeared. Robert MacThane had been absent upon some business for twenty-four hours, and it was upon his return that he found her gone. The neighbourhood was searched, but without avail, and then Robert, who was a violent man and who had adored his foreign wife, called together certain of his tenants whom he suspected, rightly or wrongly, of foul play, and had them murdered in cold blood. Murder was easy in those days, yet such an outcry was raised that Robert had to take flight, leaving his two children in the care of their nurse, and for a long while Blackwick Castle was without a master.

But its evil reputation persisted. It was said that Zaida, the witch, though dead, still made her presence felt. Many children of the tenantry and young people of the neighbourhood sickened and died – possibly of quite natural causes; but this did not prevent a mantle of terror settling upon the countryside, for it was said that Zaida had been seen – a pale woman clad in white – flitting about the cottages at night, and where she passed sickness and death were sure to supervene.

And from that time the fortune of the family gradually declined. Heir succeeded heir, but no sooner was he installed at Blackwick Castle than his nature, whatever it may previously have been, seemed to undergo a change. It was as if he absorbed into himself all the weight of evil that had stained his family name – as if he did, indeed, become a vampire, bringing blight upon any not directly connected with his own house. And so, by degrees, Blackwick was deserted of its tenantry. The land around it was left uncultivated – the farms stood empty. This had persisted to the present day, for the superstitious peasantry still told their tales of the mysterious white woman who hovered about the neighbourhood, and whose appearance betokened death – and possibly worse than death.

And yet it seemed that the last representatives of the MacThanes could not desert their ancestral home. Riches they had, sufficient to live happily upon elsewhere, but, drawn by some power they could not contend against, they had preferred to spend their lives in the solitude of the now half-ruined castle, shunned by their neighbours, feared and execrated by the few tenants that still clung to their soil.

So it had been with Jessica’s grandfather and great-grandfather. Each of them had married a young wife, and in each case their love story had been all too brief. The vampire spirit was still abroad, expressing itself – or so it seemed – through the living representatives of bygone generations of evil, and young blood had been demanded as the sacrifice.

And to them had succeeded Jessica’s father. He had not profited by their example, but had followed directly in their footsteps. And the same fate had befallen the wife whom he passionately adored. She had died of pernicious anaemia – so the doctors said – but he had regarded himself as her murderer.

But, unlike his predecessors, he had torn himself away from Blackwick – and this for the sake of his child. Unknown to her, however, he had returned year after year, for there were times when the passionate longing for the gloomy, mysterious halls and corridors of the old castle, for the wild stretches of moorland, and the dark pinewoods, would come upon him too strongly to be resisted. And so he knew that for his daughter, as for himself, there was no escape, and he warned her, when the relief of death was at last granted to him, of what her fate must be.

This was the tale that Jessica told the man who wished to make her his wife, and he made light of it, as such a man would, regarding it all as foolish superstition, the delusion of a mind overwrought. And at last – perhaps it was not very difficult, for she loved him with all her heart and soul – he succeeded in inducing Jessica to think as he did, to banish morbid ideas, as he called them, from her brain, and to consent to marry him at an early date.

‘I’ll take any risk you like,’ he declared. ‘I’ll even go and live at Blackwick if you should desire it. To think of you, my lovely Jessica, a vampire! Why, I never heard such nonsense in my life.’

‘Father said I’m very like Zaida, the witch,’ she protested, but he silenced her with a kiss.

And so they were married and spent their honeymoon abroad, and in the autumn Paul accepted an invitation to a house party in Scotland for the grouse shooting, a sport to which he was absolutely devoted, and Jessica agreed with him that there was no reason why he should forgo his pleasure.

Perhaps it was an unwise thing to do, to venture to Scotland, but by this time the young couple, more deeply in love with each other than ever, had got quite over their fears. Jessica was redolent with health and spirits, and more than once she declared that if they should be anywhere in the neighbourhood of Blackwick she would like to see the old castle out of curiosity, and just to show how absolutely she had got over the foolish terrors that used to assail her.

This seemed to Paul to be quite a wise plan, and so one day, since they were actually staying at no great distance, they motored over to Blackwick, and finding the bailiff, got him to show them over the castle.

It was a great castellated pile, grey with age, and in places falling into ruin. It stood on a steep hillside, with the rock of which it seemed to form part, and on one side of it there was a precipitous drop to a mountain stream a hundred feet below. The robber MacThanes of the old days could not have desired a better stronghold.

At the back, climbing up the mountainside were dark pinewoods, from which, here and there, rugged crags protruded, and these were fantastically shaped, some like gigantic and misshapen human forms, which stood up as if they mounted guard over the castle and the narrow gorge, by which alone it could be approached.

This gorge was always full of weird, uncanny sounds. It might have been a storehouse for the wind, which, even on calm days, rushed up and down as if seeking an escape, and it moaned among the pines and whistled in the crags and shouted derisive laughter as it was tossed from side to side of the rocky heights. It was like the plaint of lost souls – that is the expression Davenant made use of – the plaint of lost souls.

The road, little more than a track now, passed through this gorge, and then, after skirting a small but deep lake, which hardly knew the light of the sun so shut in was it by overhanging trees, climbed the hill to the castle.

And the castle! Davenant used but a few words to describe it, yet somehow I could see the gloomy edifice in my mind’s eye, and something of the lurking horror that it contained communicated itself to my brain. Perhaps my clairvoyant sense assisted me, for when he spoke of them I seemed already acquainted with the great stone halls, the long corridors, gloomy and cold even on the brightest and warmest of days, the dark, oak-panelled rooms, and the broad central staircase up which one of the early MacThanes had once led a dozen men on horseback in pursuit of a stag which had taken refuge within the precincts of the castle. There was the keep, too, its walls so thick that the ravages of time had made no impression upon them, and beneath the keep were dungeons which could tell terrible tales of ancient wrong and lingering pain.

Well, Mr and Mrs Davenant visited as much as the bailiff could show them of this ill-omened edifice, and Paul, for his part, thought pleasantly of his own Derbyshire home, the fine Georgian mansion, replete with every modern comfort, where he proposed to settle with his wife. And so he received something of a shock when, as they drove away, she slipped her hand into his and whispered:

‘Paul, you promised, didn’t you, that you would refuse me nothing?’

She had been strangely silent till she spoke those words. Paul, slightly apprehensive, assured her that she only had to ask – but the speech did not come from his heart, for he guessed vaguely what she desired.

She wanted to go and live at the castle – oh, only for a little while, for she was sure she would soon tire of it. But the bailiff had told her that there were papers, documents, which she ought to examine, since the property was now hers – and, besides, she was interested in this home of her ancestors, and wanted to explore it more thoroughly. Oh, no, she wasn’t in the least influenced by the old superstition – that wasn’t the attraction – she had quite got over those silly ideas. Paul had cured her, and since he himself was so convinced that they were without foundation he ought not to mind granting her her whim.

This was a plausible argument, not easy to controvert. In the end Paul yielded, though it was not without a struggle. He suggested amendments. Let him at least have the place done up for her – that would take time; or let them postpone their visit till next year – in the summer – not move in just as the winter was upon them.

But Jessica did not want to delay longer than she could help, and she hated the idea of redecoration. Why, it would spoil the illusion of the old place, and, besides, it would be a waste of money since she only wished to remain there for a week or two. The Derbyshire house was not quite ready yet; they must allow time for the paper to dry on the walls.

And so, a week later, when their stay with their friends was concluded, they went to Blackwick, the bailiff having engaged a few raw servants and generally made things as comfortable for them as possible. Paul was worried and apprehensive, but he could not admit this to his wife after having so loudly proclaimed his theories on the subject of superstition.

They had been married three months at this time – nine had passed since then, and they had never left Blackwick for more than a few hours – till now Paul had come to London – alone.

‘Over and over again,’ he declared, ‘my wife has begged me to go. With tears in her eyes, almost upon her knees, she has entreated me to leave her, but I have steadily refused unless she will accompany me. But that is the trouble, Mr Vance, she cannot; there is something, some mysterious horror, that holds her there as surely as if she were bound with fetters. It holds her more strongly even than it held her father – we found out that he used to spend six months at least of every year at Blackwick – months when he pretended that he was travelling abroad. You see the spell – or whatever the accursed thing may be – never really relaxed its grip of him.’

‘Did you never attempt to take your wife away?’ asked Vance.

‘Yes, several times; but it was hopeless. She would become so ill as soon as we were beyond the limit of the estate that I invariably had to take her back. Once we got as far as Dorekirk – that is the nearest town, you know – and I thought I should be successful if only I could get through the night. But she escaped me; she climbed out of a window – she meant to go back on foot, at night, all those long miles. Then I have had doctors down; but it is I who wanted the doctors, not she. They have ordered me away, but I have refused to obey them till now.’

‘Is your wife changed at all – physically?’ interrupted Vance.

Davenant reflected. ‘Changed,’ he said, ‘yes, but so subtly that I hardly know how to describe it. She is more beautiful than ever – and yet it isn’t the same beauty, if you can understand me. I have spoken of her white complexion, well, one is more than ever conscious of it now, because her lips have become so red – they are almost like a splash of blood upon her face. And the upper one has a peculiar curve that I don’t think it had before, and when she laughs she doesn’t smile…’

‘Do you know what I mean? Then her hair – it has lost its wonderful gloss. Of course, I know she is fretting about me; but that is so peculiar, too, for at times, as I have told you, she will implore me to go and leave her, and then perhaps only a few minutes later, she will wreathe her arms round my neck and say she cannot live without me. And I feel that there is a struggle going on within her, that she is only yielding slowly to the horrible influence – whatever it is – that she is herself when she begs me to go, but when she entreats me to stay- and it is then that her fascination is most intense – oh, I can’t help remembering what she told me before we were married, and that word’ – he lowered his voice – ‘the word “vampire”…’

He passed his hand over his brow that was wet with perspiration. ‘But that’s absurd, ridiculous,’ he muttered; ‘these fantastic beliefs have been exploded years ago. We live in the twentieth century.’

A pause ensued, then Vance said quietly, ‘Mr Davenant, since you have taken me into your confidence, since you have found doctors of no avail, will you let me try to help you? I think I may be of some use – if it is not already too late. Should you agree, Mr Dexter and I will accompany you, as you have suggested, to Blackwick Castle as early as possible – by tonight’s mail North. Under ordinary circumstances I should tell you as you value your life, not to return….’

Davenant shook his head. ‘That is advice which I should never take,’ he declared. ‘I had already decided, under any circumstances, to travel North tonight. I am glad that you both will accompany me.’

And so it was decided. We settled to meet at the station, and presently Paul Davenant took his departure. Any other details that remained to be told he would put us in possession of during the course of the journey.

‘A curious and most interesting case,’ remarked Vance when we were alone. ‘What do you make of it, Dexter?’

‘I suppose,’ I replied cautiously, ‘that there is such a thing as vampirism even in these days of advanced civilization? I can understand the evil influence that a very old person may have upon a young one if they happen to be in constant intercourse – the worn-out tissue sapping healthy vitality for their own support. And there are certain people – I could think of several myself – who seem to depress one and undermine one’s energies, quite unconsciously, of course, but one feels somehow that vitality has passed from oneself to them. And in this case, when the force is centuries old, expressing itself, in some mysterious way, through Davenant’s wife, is it not feasible to believe that he may be physically affected by it, even though the whole thing is sheerly mental?’

‘You think, then,’ demanded Vance, ‘that it is sheerly mental? Tell me, if that is so, how do you account for the marks on Davenant’s throat?’

This was a question to which I found no reply, and though I pressed him for his views, Vance would not commit himself further just then.

Of our long journey to Scotland I need say nothing. We did not reach Blackwick Castle till late in the afternoon of the following day. The place was just as I had conceived it – as I have already described it. And a sense of gloom settled upon me as our car jolted us over the rough road that led through the Gorge of the Winds – a gloom that deepened when we penetrated into the vast cold hall of the castle.

Mrs Davenant, who had been informed by telegram of our arrival, received us cordially. She knew nothing of our actual mission, regarding us merely as friends of her husband’s. She was most solicitous on his behalf, but there was something strained about her tone, and it made me feel vaguely uneasy. The impression that I got was that the woman was impelled to everything that she said or did by some force outside herself – but, of course, this was a conclusion that the circumstances I was aware of might easily have conduced to. In every other aspect she was charming, and she had an extraordinary fascination of appearance and manner that made me readily understand the force of a remark made by Davenant during our journey.

‘I want to live for Jessica’s sake. Get her away from Blackwick, Vance, and I feel that all will be well. I’d go through hell to have her restored to me – as she was.’

And now that I had seen Mrs Davenant I realised what he meant by those last words. Her fascination was stronger than ever, but it was not a natural fascination – not that of a normal woman, such as she had been. It was the fascination of a Circe, of a witch, of an enchantress – and as such was irresistible.

We had a strong proof of the evil within her soon after our arrival. It was a test that Vance had quietly prepared. Davenant had mentioned that no flowers grew at Blackwick, and Vance declared that we must take some with us as a present for the lady of the house. He purchased a bouquet of pure white roses at the little town where we left the train, for the motorcar had been sent to meet us. Soon after our arrival he presented these to Mrs Davenant. She took them it seemed to me nervously, and hardly had her hand touched them before they fell to pieces, in a shower of crumpled petals, to the floor.

‘We must act at once,’ said Vance to me when we were descending to dinner that night. ‘There must be no delay.’

‘What are you afraid of?’ I whispered.

‘Davenant has been absent a week,’ he replied grimly. ‘He is stronger than when he went away, but not strong enough to survive the loss of more blood. He must be protected. There is danger tonight.’

‘You mean from his wife?’ I shuddered at the ghastliness of the suggestion.

‘That is what time will show.’ Vance turned to me and added a few words with intense earnestness. ‘Mrs Davenant, Dexter, is at present hovering between two conditions. The evil thing has not yet completely mastered her – you remember what Davenant said, how she would beg him to go away and the next moment entreat him to stay? She has made a struggle, but she is gradually succumbing, and this last week, spent here alone, has strengthened the evil. And that is what I have got to fight, Dexter – it is to be a contest of will, a contest that will go on silently till one or the other obtains the mastery. If you watch, you may see. Should a change show itself in Mrs Davenant you will know that I have won.’

Thus I knew the direction in which my friend proposed to act. It was to be a war of his will against the mysterious power that had laid its curse upon the house of MacThane. Mrs Davenant must be released from the fatal charm that held her.