Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

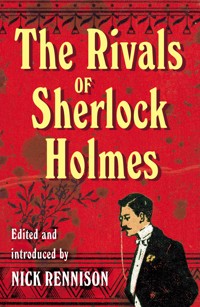

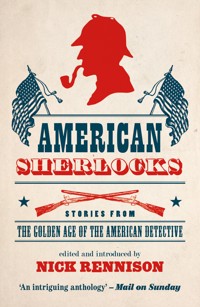

Sherlock Holmes is the most famous of all fictional detectives but, across the Atlantic, he had plenty of rivals. Between 1890 and 1920, American writers created dozens and dozens of crime-solvers. In this thrilling, unusual anthology, editor Nick Rennison gathers together 15 often neglected tales to highlight American crime fiction's early years. The detectives that feature include Professor Augustus SFX Van Dusen, 'The Thinking Machine', even more cerebral than Holmes; Craig Kennedy, the so-called 'scientific detective'; Uncle Abner, a shrewd backwoodsman in pre-Civil War Virginia; Violet Strange, New York debutante turned criminologist; and Nick Carter, the original pulp private eye.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 600

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR NICK RENNISON’S ANTHOLOGIES

‘An intriguing anthology’ – Mail on Sunday

‘These 15 sanguinary spine-tinglers… deliver delicious chills’ – Christopher Hirst, Independent

‘A book which will delight fans of crime fiction’ – Verbal Magazine

‘It’s good to see that Mr Rennison has also selected some rarer pieces – and rarer detectives, such as November Joe, Sebastian Zambra, Cecil Thorold and Lois Cayley’ – Roger Johnson,The District Messenger (Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London)

‘A gloriously Gothic collection of heroes fighting against maidens with bone-white skin, glittering eyes and bloodthirsty intentions’ – Lizzie Hayes, Promoting Crime Fiction

‘Nick Rennison’s The Rivals of Dracula shows that many Victorian and Edwardian novelists tried their hand at this staple of Gothic horror’ – Andrew Taylor, Spectator

‘The Rivals of Dracula is a fantastic collection of classic tales to chill the blood and tingle the spine. Grab a copy and curl up somewhere cosy for a night in’ – Citizen Homme Magazine

INTRODUCTION

We all have a picture in our minds of the archetypal detective of American fiction. The hardboiled, wisecracking private eye, walking a city’s mean streets. Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade, Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or one of the hundreds, probably thousands, of other gumshoes who have trodden in their footsteps. But that style of detective only came into being in the late 1920s and early 1930s, most influentially in Hammett’s novels and in the pages of the legendary magazine Black Mask. American crime fiction has a much longer history.

It really begins with Edgar Allan Poe. (The history of most genre fiction in the USA really begins with Edgar Allan Poe.) Claims for precedence have been made on behalf of earlier works such as Charles Brockden Brown’s 1799 novel Edgar Huntly and some of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s shorter fiction. However, it was Poe who established many of the tropes of crime fiction which are still being used by writers today. In three short stories published in the 1840s – ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’, ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’ and ‘The Purloined Letter’ – he created the templates for much of what was to come. The locked-room mystery; the story based on a true crime; the clues, sometimes hidden in plain sight, which point towards a satisfying explanation of what initially seems inexplicable; the bumbling police outshone by the brilliant amateur. All of these derive ultimately from what Poe himself called his ‘tales of ratiocination’. His character C Auguste Dupin is the archetype of the detective hero with superior powers of deduction and his influence on later creations, most notably Sherlock Holmes, is clear.

Yet Poe’s impact was not markedly felt in his own country in the decades immediately following his death in 1849. There are stories and novels from the 1850s and 1860s which can be classed retrospectively as crime fiction. The Dead Letter of 1866 by Seeley Regester (the pseudonym of the woman writer Metta Victoria Fuller Victor), for instance, is the story of the narrator’s quest to track down a murderer. Another female author, Harriet Spofford, created what was arguably one of the first ‘series’ detectives in history in Mr Furbush who appeared in several stories published in Harper’s New MonthlyMagazine. However, the genre Poe had pioneered did not gain much more than a toehold in the traditional publishing houses and magazines of the American literary world.

It was in the more downmarket arena of the so-called ‘dime novel’ that the figure of the detective finally emerged from the wings and, often enough, took centre stage. The equivalent of the British ‘penny dreadful’, the dime novel began to flourish in the 1860s. The first example of the genre is usually said to be Malaeska, the Indian Wife of the Great Hunter, written by a prolific author and editor, Ann S Stephens, and published by the firm of Beadle & Adams in 1860. Thousands of titles followed in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the opening ones of the twentieth. Several factors fuelled this explosion in cheap genre fiction. Literacy levels began to increase around the time of the American Civil War and continued to do so in the years between 1870 and 1900. At the same time, new printing technologies meant that publishers could issue more books at cheaper prices.

As the title of Ann Stephens’s original dime novel indicates, tales of Native Americans and what was increasingly becoming known as the ‘Wild West’ were popular. The army scout and bison hunter William Cody was transformed into the national hero ‘Buffalo Bill’ by the adventures attributed to him in stories by writers such as Ned Buntline and Prentiss Ingraham. Other genres thrived as well. One of these was the detective novel. Characters like ‘Old Sleuth’, ‘Lady Kate, the Dashing Female Detective’, ‘Sam Strong the Cowboy Detective’ and ‘Old King Brady’ battled bad guys in stories that made up in lively action for what they lacked in literary sophistication. However, the major detective to emerge from the dime novel was Nick Carter.

After his first appearance in the New York Weekly in 1886, Carter soon graduated to his own series, the Nick Carter Weekly. A square-jawed, two-fisted, all-American hero, Carter proved to be a character of astonishing longevity. Transformed into a kind of sub-James Bond figure, he appeared in dozens of cheap paperbacks in the 1960s and new stories about him were still appearing in the early 1990s. In his earliest incarnations, he was kept busy righting wrongs across America and around the world in a series of breath-taking and occasionally fantastical adventures. He gathered about him a small platoon of willing assistants and faced a rogues’ gallery of memorable opponents, including the supervillain Doctor Quartz, Dazaar the Arch Fiend, and Zanoni the Woman Wizard. Authors such as Frederick van Rensselaer Day, George C Jenks and Thomas C Harbaugh churned out scores of stories which were published anonymously or attributed to the fictional ‘Chick Carter’, Nick’s adopted son. After the success of Sherlock Holmes in America, Carter evolved into a more traditional gentleman detective, mainly operating in New York, and I have included a typical tale from this period in this anthology.

During the heyday of the dime novel, crime fiction gradually gained popularity in more upmarket fiction. Many of these new crime novels, appearing under the imprint of publishers who would have turned their noses up at the likes of Nick Carter and ‘Old Sleuth’, were by women writers. The Leavenworth Case, for example,was the work ofAnna Katharine Green, a Brooklyn-born author who turned to fiction after failing to make much of a mark as a poet. First published in 1878, this introduced a detective from the New York Metropolitan Police Force named Ebenezer Gryce who went on to feature in a number of Green’s later novels. Although The Leavenworth Case is very much a novel of its time, it continued to have an influence well into the twentieth century. Agatha Christie later cited the book as an inspiration for her when she was just setting out on her career. (Green herself was still writing in the 1920s and created other recurring characters, including nosy spinster Amelia Butterworth, a prototype Miss Marple, and Violet Strange, a wealthy young New Yorker moonlighting as a detective, who features in one of the stories in this anthology.)

The Leavenworth Case was a bestseller and other crime novels of the 1870s and 1880s made their mark. By the early 1890s the figure of the fictional detective was firmly established with readers of both ‘downmarket’ and ‘upmarket’ literature. However, one character was about to change the ways in which they all imagined that figure. His name, of course, was Sherlock Holmes. His impact was to be felt almost as profoundly in the USA as it was in Britain. Although the first Holmes tale, the novel A Study in Scarlet, had to wait more than two years for an American edition, the stories after that appeared almost simultaneously in the UK and across the Atlantic. Indeed, in some instances, Americans could enjoy Holmes’s latest adventure before his home readership. Some of the stories later collected in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, for example, were published in the US Collier’s magazinea week or two prior to their appearances in the UK Strand Magazine.

The Sherlock Holmes effect was soon evident. Just as in Britain, scores upon scores of rivals made their bow in books and magazines in the years between 1880 and 1920. Of the characters who feature in the stories in this anthology, it is difficult to believe that Bromley Barnes, LeDroit Conners, Craig Kennedy and others would have been created in quite the same way without the influence of Doyle’s great detective. They all carry echoes of the man from Baker Street’s genius and personality. And Ellis Parker Butler’s Philo Gubb, the inept ‘hero’ of a series of comic crime stories, may be the polar opposite of Doyle’s hero in terms of intellectual prowess but even he was an avowed admirer of Holmes.

A host of other American fictional detectives, not included in this anthology, largely for reasons of space, also operate in the shadow of Sherlock. ‘Average’ Jones, the creation of the muckraking journalist Samuel Hopkins Adams, may seem something of an original in that he comes across all his cases through the classified ads of the daily newspapers but even that idiosyncrasy is an echo of Holmes’s abiding interest in the agony column of The Times. Luther Trant, the so-called ‘psychological detective’ who was the invention of William MacHarg and Edwin Balmer, was hailed in the magazine that published their first story in 1909 as propounding a ‘new detective theory… as important as Poe’s deductive theory of ratiocination’. Yet readers of Conan Doyle could have pointed to the pages of The Strand Magazine and justifiably disputed its novelty.

All these detectives, whether included in this anthology or not, had distinctly American attributes but equally they all owed something to the man from Baker Street. Only a handful of characters escaped the influence of Conan Doyle almost entirely. Perhaps the most original of all the American detectives of this period was Uncle Abner, the creation of the lawyer and author Melville Davisson Post. Post turned to the past as the setting for the 22 stories which feature his God-fearing hero, dispensing wisdom and justice as he rides through the backwoods of West Virginia in the years before the American Civil War, under the admiring gaze of the narrator, his young nephew Martin. Although largely forgotten today, the Uncle Abner stories have had many admirers over the years since their first publication. In 1941, Howard Haycraft, one of the first literary critics to take crime fiction seriously, called Post’s character ‘the greatest American contribution’ to the cast list of detective fiction since Poe’s C Auguste Dupin. The opening story in American Sherlocks, I hope, will introduce Uncle Abner to new readers.

Even readers with a wide-ranging knowledge of the genre have a tendency to assume that little American crime fiction of any interest appeared in the eighty or so years between Poe’s stories and 1920s novels by such writers as SS Van Dine, creator of Philo Vance, and Dashiell Hammett, whose first book, Red Harvest, was published as that decade came to an end. One aim of my anthology is to show how wrong that assumption is. There are many crime stories from the period between 1880 and 1920 which are well worth discovering. Stories of women detectives like Hugh Cosgro Weir’s Madelyn Mack and Anna Katharine Green’s Violet Strange. Stories of hyper-cerebral geniuses like Jacques Futrelle’s ‘Thinking Machine’, Professor Augustus SFX Van Dusen. Stories of pioneering scientific criminologists like Arthur Reeve’s Craig Kennedy. From the blind detective Thornley Colton to the retired Secret Service agent Bromley Barnes, the pages of American magazines were filled with intriguing characters whose exploits remain very enjoyable. Here are fifteen of them.

UNCLE ABNER

Created by Melville Davisson Post (1869-1930)

Melville Davisson Post was born in West Virginia, the son of a wealthy landowner. He practised law for some years and during this time he published his first stories – about the unscrupulous lawyer Randolph Mason. After giving up the law because of ill-health, Post became one of the most popular American mystery writers of the first decades of the twentieth century. For some years after his death, following a fall from his horse, he was regularly cited in studies and histories of the genre. Yet today he is hardly known. Post created a number of detectives (Sir Henry Marquis of Scotland Yard, a French policeman named Jonquelle) but his most admired and original character was Uncle Abner, a shrewd, God-fearing West Virginian backwoodsman solving mysteries in pre-Civil War America, who appeared in 22 stories published between 1911 and 1928. Eighteen of them were collected in Uncle Abner, Master of Mysteries, published in 1918. These tales, most of them narrated by Abner’s admiring young nephew Martin, are very much of their time (some of the language used about black Americans can be off-putting for modern readers) but they are also very skilfully constructed and remain compelling reading. ‘The Doomdorf Mystery’, a clever variant on the locked-room tale, is one of the best of them.

THE DOOMDORF MYSTERY

The pioneer was not the only man in the great mountains behind Virginia. Strange aliens drifted in after the Colonial wars. All foreign armies are sprinkled with a cockle of adventurers that take root and remain. They were with Braddock and La Salle, and they rode north out of Mexico after her many empires went to pieces.

I think Doomdorf crossed the seas with Iturbide when that ill-starred adventurer returned to be shot against a wall; but there was no Southern blood in him. He came from some European race remote and barbaric. The evidences were all about him. He was a huge figure of a man, with a black spade beard, broad, thick hands, and square, flat fingers.

He had found a wedge of land between the Crown’s grant to Daniel Davisson and a Washington survey. It was an uncovered triangle not worth the running of the lines; and so, no doubt, was left out, a sheer rock standing up out of the river for a base, and a peak of the mountain rising northward behind it for an apex.

Doomdorf squatted on the rock. He must have brought a belt of gold pieces when he took to his horse, for he hired old Robert Steuart’s slaves and built a stone house on the rock, and he brought the furnishings overland from a frigate in the Chesapeake; and then in the handfuls of earth, wherever a root would hold, he planted the mountain behind his house with peach trees. The gold gave out; but the devil is fertile in resources. Doomdorf built a log still and turned the first fruits of the garden into a hell-brew. The idle and the vicious came with their stone jugs, and violence and riot flowed out.

The government of Virginia was remote and its arm short and feeble; but the men who held the lands west of the mountains against the savages under grants from George, and after that held them against George himself, were efficient and expeditious. They had long patience, but when that failed they went up from their fields and drove the thing before them out of the land, like a scourge of God.

There came a day, then, when my Uncle Abner and Squire Randolph rode through the gap of the mountains to have the thing out with Doomdorf. The work of this brew, which had the odors of Eden and the impulses of the devil in it, could be borne no longer. The drunken negros had shot old Duncan’s cattle and burned his haystacks, and the land was on its feet.

They rode alone, but they were worth an army of little men. Randolph was vain and pompous and given over to extravagance of words, but he was a gentleman beneath it, and fear was an alien and a stranger to him. And Abner was the right hand of the land.

It was a day in early summer and the sun lay hot. They crossed through the broken spine of the mountains and trailed along the river in the shade of the great chestnut trees. The road was only a path and the horses went one before the other. It left the river when the rock began to rise and, making a detour through the grove of peach trees, reached the house on the mountain side. Randolph and Abner got down, unsaddled their horses and turned them out to graze, for their business with Doomdorf would not be over in an hour. Then they took a steep path that brought them out on the mountain side of the house.

A man sat on a big red-roan horse in the paved court before the door. He was a gaunt old man. He sat bare-headed, the palms of his hands resting on the pommel of his saddle, his chin sunk in his black stock, his face in retrospection, the wind moving gently his great shock of voluminous white hair. Under him the huge red horse stood with his legs spread out like a horse of stone.

There was no sound. The door to the house was closed; insects moved in the sun; a shadow crept out from the motionless figure, and swarms of yellow butterflies manoeuvred like an army.

Abner and Randolph stopped. They knew the tragic figure – a circuit rider of the hills who preached the invective of Isaiah as though he were the mouthpiece of a militant and avenging overlord; as though the government of Virginia were the awful theocracy of the Book of Kings. The horse was dripping with sweat and the man bore the dust and the evidences of a journey on him.

‘Bronson,’ said Abner, ‘where is Doomdorf?’

The old man lifted his head and looked down at Abner over the pommel of the saddle.

‘“Surely,”’ he said, ‘“he covereth his feet in his summer chamber.”’

Abner went over and knocked on the closed door, and presently the white, frightened face of a woman looked out at him. She was a little, faded woman, with fair hair, a broad foreign face, but with the delicate evidences of gentle blood.

Abner repeated his question.

‘Where is Doomdorf?’

‘Oh, sir,’ she answered with a queer lisping accent, ‘he went to lie down in his south room after his midday meal, as his custom is; and I went to the orchard to gather any fruit that might be ripened.’ She hesitated and her voice lisped into a whisper: ‘He is not come out and I cannot wake him.’

The two men followed her through the hall and up the stairway to the door.

‘It is always bolted,’ she said, ‘when he goes to lie down.’ And she knocked feebly with the tips of her fingers.

There was no answer and Randolph rattled the doorknob.

‘Come out, Doomdorf!’ he called in his big, bellowing voice.

There was only silence and the echoes of the words among the rafters. Then Randolph set his shoulder to the door and burst it open.

They went in. The room was flooded with sun from the tall south windows. Doomdorf lay on a couch in a little offset of the room, a great scarlet patch on his bosom and a pool of scarlet on the floor.

The woman stood for a moment staring; then she cried out:

‘At last I have killed him!’ And she ran like a frightened hare.

The two men closed the door and went over to the couch. Doomdorf had been shot to death. There was a great ragged hole in his waistcoat. They began to look about for the weapon with which the deed had been accomplished, and in a moment found it – a fowling piece lying in two dogwood forks against the wall. The gun had just been fired; there was a freshly exploded paper cap under the hammer.

There was little else in the room – a loom-woven rag carpet on the floor; wooden shutters flung back from the windows; a great oak table, and on it a big, round, glass water bottle, filled to its glass stopper with raw liquor from the still. The stuff was limpid and clear as spring water; and, but for its pungent odor, one would have taken it for God’s brew instead of Doomdorf’s. The sun lay on it and against the wall where hung the weapon that had ejected the dead man out of life.

‘Abner,’ said Randolph, ‘this is murder! The woman took that gun down from the wall and shot Doomdorf while he slept.’

Abner was standing by the table, his fingers round his chin.

‘Randolph,’ he replied, ‘what brought Bronson here?’

‘The same outrages that brought us,’ said Randolph. ‘The mad old circuit rider has been preaching a crusade against Doomdorf far and wide in the hills.’

Abner answered, without taking his fingers from about his chin:

‘You think this woman killed Doomdorf? Well, let us go and ask Bronson who killed him.’

They closed the door, leaving the dead man on his couch, and went down into the court.

The old circuit rider had put away his horse and got an ax. He had taken off his coat and pushed his shirtsleeves up over his long elbows. He was on his way to the still to destroy the barrels of liquor. He stopped when the two men came out, and Abner called to him.

‘Bronson,’ he said, ‘who killed Doomdorf?’

‘I killed him,’ replied the old man, and went on toward the still.

Randolph swore under his breath. ‘By the Almighty,’ he said, ‘everybody couldn’t kill him!’

‘Who can tell how many had a hand in it?’ replied Abner.

‘Two have confessed!’ cried Randolph. ‘Was there perhaps a third? Did you kill him, Abner? And I too? Man, the thing is impossible!’

‘The impossible,’ replied Abner, ‘looks here like the truth. Come with me, Randolph, and I will show you a thing more impossible than this.’

They returned through the house and up the stairs to the room. Abner closed the door behind them.

‘Look at this bolt,’ he said; ‘it is on the inside and not connected with the lock. How did the one who killed Doomdorf get into this room, since the door was bolted?’

‘Through the windows,’ replied Randolph.

There were but two windows, facing the south, through which the sun entered. Abner led Randolph to them.

‘Look!’ he said. ‘The wall of the house is plumb with the sheer face of the rock. It is a hundred feet to the river and the rock is as smooth as a sheet of glass. But that is not all. Look at these window frames; they are cemented into their casement with dust and they are bound along their edges with cobwebs. These windows have not been opened. How did the assassin enter?’

‘The answer is evident,’ said Randolph: ‘The one who killed Doomdorf hid in the room until he was asleep; then he shot him and went out.’

‘The explanation is excellent but for one thing,’ replied Abner: ‘How did the assassin bolt the door behind him on the inside of this room after he had gone out?’

Randolph flung out his arms with a hopeless gesture.

‘Who knows?’ he cried. ‘Maybe Doomdorf killed himself.’

Abner laughed.

‘And after firing a handful of shot into his heart he got up and put the gun back carefully into the forks against the wall!’

‘Well,’ cried Randolph, ‘there is one open road out of this mystery. Bronson and this woman say they killed Doomdorf, and if they killed him they surely know how they did it. Let us go down and ask them.’

‘In the law court,’ replied Abner, ‘that procedure would be considered sound sense; but we are in God’s court and things are managed there in a somewhat stranger way. Before we go let us find out, if we can, at what hour it was that Doomdorf died.’

He went over and took a big silver watch out of the dead man’s pocket. It was broken by a shot and the hands lay at one hour after noon. He stood for a moment fingering his chin.

‘At one o’clock,’ he said. ‘Bronson, I think, was on the road to this place, and the woman was on the mountain among the peach trees.’

Randolph threw back his shoulders.

‘Why waste time in a speculation about it, Abner?’ he said. ‘We know who did this thing. Let us go and get the story of it out of their own mouths. Doomdorf died by the hands of either Bronson or this woman.’

‘I could better believe it,’ replied Abner, ‘but for the running of a certain awful law.’

‘What law?’ said Randolph. ‘Is it a statute of Virginia?’

‘It is a statute,’ replied Abner, ‘of an authority somewhat higher. Mark the language of it: “He that killeth with the sword must be killed with the sword.”’

He came over and took Randolph by the arm.

‘Must! Randolph, did you mark particularly the word “must”? It is a mandatory law. There is no room in it for the vicissitudes of chance or fortune. There is no way round that word. Thus, we reap what we sow and nothing else; thus, we receive what we give and nothing else. It is the weapon in our own hands that finally destroys us. You are looking at it now.’ And he turned him about so that the table and the weapon and the dead man were before him. ‘“He that killeth with the sword must be killed with the sword.” And now,’ he said, ‘let us go and try the method of the law courts. Your faith is in the wisdom of their ways.’

They found the old circuit rider at work in the still, staving in Doomdorf’s liquor casks, splitting the oak heads with his ax.

‘Bronson,’ said Randolph, ‘how did you kill Doomdorf?’

The old man stopped and stood leaning on his ax.

‘I killed him,’ replied the old man, ‘as Elijah killed the captains of Ahaziah and their fifties. But not by the hand of any man did I pray the Lord God to destroy Doomdorf, but with fire from heaven to destroy him.’

He stood up and extended his arms.

‘His hands were full of blood,’ he said. ‘With his abomination from these groves of Baal he stirred up the people to contention, to strife and murder. The widow and the orphan cried to heaven against him. “I will surely hear their cry,” is the promise written in the Book. The land was weary of him; and I prayed the Lord God to destroy him with fire from heaven, as he destroyed the Princes of Gomorrah in their palaces!’

Randolph made a gesture as of one who dismisses the impossible, but Abner’s face took on a deep, strange look.

‘With fire from heaven!’ he repeated slowly to himself. Then he asked a question. ‘A little while ago,’ he said, ‘when we came, I asked you where Doomdorf was, and you answered me in the language of the third chapter of the Book of Judges. Why did you answer me like that, Bronson? – “Surely he covereth his feet in his summer chamber.”’

‘The woman told me that he had not come down from the room where he had gone up to sleep,’ replied the old man, ‘and that the door was locked. And then I knew that he was dead in his summer chamber like Eglon, King of Moab.’

He extended his arm toward the south.

‘I came here from the Great Valley,’ he said, ‘to cut down these groves of Baal and to empty out this abomination; but I did not know that the Lord had heard my prayer and visited His wrath on Doomdorf until I was come up into these mountains to his door. When the woman spoke I knew it.’ And he went away to his horse, leaving the ax among the ruined barrels.

Randolph interrupted.

‘Come, Abner,’ he said; ‘this is wasted time. Bronson did not kill Doomdorf.’

Abner answered slowly in his deep, level voice:

‘Do you realize, Randolph, how Doomdorf died?’

‘Not by fire from heaven, at any rate,’ said Randolph.

‘Randolph,’ replied Abner, ‘are you sure?’

‘Abner,’ cried Randolph, ‘you are pleased to jest, but I am in deadly earnest. A crime has been done here against the state. I am an officer of justice and I propose to discover the assassin if I can.’

He walked away toward the house and Abner followed, his hands behind him and his great shoulders thrown loosely forward, with a grim smile about his mouth.

‘It is no use to talk with the mad old preacher,’ Randolph went on. ‘Let him empty out the liquor and ride away. I won’t issue a warrant against him. Prayer may be a handy implement to do a murder with, Abner, but it is not a deadly weapon under the statutes of Virginia. Doomdorf was dead when old Bronson got here with his Scriptural jargon. This woman killed Doomdorf. I shall put her to an inquisition.’

‘As you like,’ replied Abner. ‘Your faith remains in the methods of the law courts.’

‘Do you know of any better methods?’ said Randolph.

‘Perhaps,’ replied Abner, ‘when you have finished.’

Night had entered the valley. The two men went into the house and set about preparing the corpse for burial. They got candles, and made a coffin, and put Doomdorf in it, and straightened out his limbs, and folded his arms across his shot-out heart. Then they set the coffin on benches in the hall.

They kindled a fire in the dining room and sat down before it, with the door open and the red firelight shining through on the dead man’s narrow, everlasting house. The woman had put some cold meat, a golden cheese and a loaf on the table. They did not see her, but they heard her moving about the house; and finally, on the gravel court outside, her step and the whinny of a horse. Then she came in, dressed as for a journey. Randolph sprang up.

‘Where are you going?’ he said.

‘To the sea and a ship,’ replied the woman. Then she indicated the hall with a gesture. ‘He is dead and I am free.’

There was a sudden illumination in her face. Randolph took a step toward her. His voice was big and harsh.

‘Who killed Doomdorf?’ he cried.

‘I killed him,’ replied the woman. ‘It was fair!’

‘Fair!’ echoed the justice. ‘What do you mean by that?’

The woman shrugged her shoulders and put out her hands with a foreign gesture.

‘I remember an old, old man sitting against a sunny wall, and a little girl, and one who came and talked a long time with the old man, while the little girl plucked yellow flowers out of the grass and put them into her hair. Then finally the stranger gave the old man a gold chain and took the little girl away.’ She flung out her hands. ‘Oh, it was fair to kill him!’ She looked up with a queer, pathetic smile.

‘The old man will be gone by now,’ she said; ‘but I shall perhaps find the wall there, with the sun on it, and the yellow flowers in the grass. And now, may I go?’

It is a law of the story-teller’s art that he does not tell a story. It is the listener who tells it. The story-teller does but provide him with the stimuli.

Randolph got up and walked about the floor. He was a justice of the peace in a day when that office was filled only by the landed gentry, after the English fashion; and the obligations of the law were strong on him. If he should take liberties with the letter of it, how could the weak and the evil be made to hold it in respect? Here was this woman before him a confessed assassin. Could he let her go?

Abner sat unmoving by the hearth, his elbow on the arm of his chair, his palm propping up his jaw, his face clouded in deep lines. Randolph was consumed with vanity and the weakness of ostentation, but he shouldered his duties for himself. Presently he stopped and looked at the woman, wan, faded like some prisoner of legend escaped out of fabled dungeons into the sun.

The firelight flickered past her to the box on the benches in the hall, and the vast, inscrutable justice of heaven entered and overcame him.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Go! There is no jury in Virginia that would hold a woman for shooting a beast like that.’ And he thrust out his arm, with the fingers extended toward the dead man.

The woman made a little awkward curtsy.

‘I thank you, sir.’ Then she hesitated and lisped, ‘But I have not shoot him.’

‘Not shoot him!’ cried Randolph. ‘Why, the man’s heart is riddled!’

‘Yes, sir,’ she said simply, like a child. ‘I kill him, but have not shoot him.’

Randolph took two long strides toward the woman.

‘Not shoot him!’ he repeated. ‘How then, in the name of heaven, did you kill Doomdorf?’ And his big voice filled the empty places of the room.

‘I will show you, sir,’ she said.

She turned and went away into the house. Presently she returned with something folded up in a linen towel. She put it on the table between the loaf of bread and the yellow cheese.

Randolph stood over the table, and the woman’s deft fingers undid the towel from round its deadly contents; and presently the thing lay there uncovered.

It was a little crude model of a human figure done in wax with a needle thrust through the bosom.

Randolph stood up with a great intake of the breath.

‘Magic! By the eternal!’

‘Yes, sir,’ the woman explained, in her voice and manner of a child. ‘I have try to kill him many times – oh, very many times! – with witch words which I have remember; but always they fail. Then, at last, I make him in wax, and I put a needle through his heart; and I kill him very quickly.’

It was as clear as daylight, even to Randolph, that the woman was innocent. Her little harmless magic was the pathetic effort of a child to kill a dragon. He hesitated a moment before he spoke, and then he decided like the gentleman he was. If it helped the child to believe that her enchanted straw had slain the monster – well, he would let her believe it.

‘And now, sir, may I go?’

Randolph looked at the woman in a sort of wonder.

‘Are you not afraid,’ he said, ‘of the night and the mountains, and the long road?’

‘Oh no, sir,’ she replied simply. ‘The good God will be everywhere now.’

It was an awful commentary on the dead man – that this strange half-child believed that all the evil in the world had gone out with him; that now that he was dead, the sunlight of heaven would fill every nook and corner.

It was not a faith that either of the two men wished to shatter, and they let her go. It would be daylight presently and the road through the mountains to the Chesapeake was open.

Randolph came back to the fireside after he had helped her into the saddle, and sat down. He tapped on the hearth for some time idly with the iron poker; and then finally he spoke.

‘This is the strangest thing that ever happened,’ he said. ‘Here’s a mad old preacher who thinks that he killed Doomdorf with fire from Heaven, like Elijah the Tishbite; and here is a simple child of a woman who thinks she killed him with a piece of magic of the Middle Ages – each as innocent of his death as I am. And yet, by the eternal, the beast is dead!’

He drummed on the hearth with the poker, lifting it up and letting it drop through the hollow of his fingers.

‘Somebody shot Doomdorf. But who? And how did he get into and out of that shut-up room? The assassin that killed Doomdorf must have gotten into the room to kill him. Now, how did he get in?’ He spoke as to himself; but my uncle sitting across the hearth replied:

‘Through the window.’

‘Through the window!’ echoed Randolph. ‘Why, man, you yourself showed me that the window had not been opened, and the precipice below it a fly could hardly climb. Do you tell me now that the window was opened?’

‘No,’ said Abner, ‘it was never opened.’

Randolph got on his feet.

‘Abner,’ he cried, ‘are you saying that the one who killed Doomdorf climbed the sheer wall and got in through a closed window, without disturbing the dust or the cobwebs on the window frame?’

My uncle looked Randolph in the face.

‘The murderer of Doomdorf did even more,’ he said. ‘That assassin not only climbed the face of that precipice and got in through the closed window, but he shot Doomdorf to death and got out again through the closed window without leaving a single track or trace behind, and without disturbing a grain of dust or a thread of a cobweb.’

Randolph swore a great oath.

‘The thing is impossible!’ he cried. ‘Men are not killed today in Virginia by black art or a curse of God.’

‘By black art, no,’ replied Abner; ‘but by the curse of God, yes. I think they are.’

Randolph drove his clenched right hand into the palm of his left.

‘By the eternal!’ he cried. ‘I would like to see the assassin who could do a murder like this, whether he be an imp from the pit or an angel out of Heaven.’

‘Very well,’ replied Abner, undisturbed. ‘When he comes back tomorrow I will show you the assassin who killed Doomdorf.’

When day broke they dug a grave and buried the dead man against the mountain among his peach trees. It was noon when that work was ended. Abner threw down his spade and looked up at the sun.

‘Randolph,’ he said, ‘let us go and lay an ambush for this assassin. He is on the way here.’

And it was a strange ambush that he laid. When they were come again into the chamber where Doomdorf died he bolted the door; then he loaded the fowling piece and put it carefully back on its rack against the wall. After that he did another curious thing: He took the blood-stained coat, which they had stripped off the dead man when they had prepared his body for the earth, put a pillow in it and laid it on the couch precisely where Doomdorf had slept. And while he did these things Randolph stood in wonder and Abner talked:

‘Look you, Randolph… We will trick the murderer… We will catch him in the act.’

Then he went over and took the puzzled justice by the arm.

‘Watch!’ he said. ‘The assassin is coming along the wall!’

But Randolph heard nothing, saw nothing. Only the sun entered. Abner’s hand tightened on his arm.

‘It is here! Look!’ And he pointed to the wall.

Randolph, following the extended finger, saw a tiny brilliant disk of light moving slowly up the wall toward the lock of the fowling piece. Abner’s hand became a vise and his voice rang as over metal.

‘“He that killeth with the sword must be killed with the sword.” It is the water bottle, full of Doomdorf’s liquor, focusing the sun… And look, Randolph, how Bronson’s prayer was answered!’

The tiny disk of light traveled on the plate of the lock.

‘It is fire from heaven!’

The words rang above the roar of the fowling piece, and Randolph saw the dead man’s coat leap up on the couch, riddled by the shot. The gun, in its natural position on the rack, pointed to the couch standing at the end of the chamber, beyond the offset of the wall, and the focused sun had exploded the percussion cap.

Randolph made a great gesture, with his arm extended.

‘It is a world,’ he said, ‘filled with the mysterious joinder of accident!’

‘It is a world,’ replied Abner, ‘filled with the mysterious justice of God!’

BROMLEY BARNES

Created by George Barton (1866-1940)

A former Secret Service agent with thirty years’ experience, Bromley Barnes is supposedly retired from US government work but government seems incapable of functioning well without him. In the stories by George Barton, the sophisticated Mr Barnes, a collector of first editions and connoisseur of fine living, is regularly called back to deal with sensitive investigations in both Washington and New York. He looks into the mysterious death of an inventor, identifies the source of a series of White House leaks and thwarts a bomb attack on the National Arsenal. Many of the tales in the 1918 volume The Strange Adventures of Bromley Barnesare closer to spy fiction than crime fiction but ‘Adventure of the Cleopatra Necklace’, in which Bromley Barnes tracks down the man who stole a priceless Ancient Egyptian artefact from the renowned ‘Cosmopolitan Museum’, is a fairly traditional detective story. Barnes, who also appeared in a 1920 novel entitled The Pembroke Mason Affair, was the creation of George Barton, a regular contributor to story magazines throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century. In addition, Barton compiled a number of non-fiction works with titles such as Adventures of the World’s Greatest Detectives, Celebrated Crimes and Their Solutions, and The World’s Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service Agents.

ADVENTURE OF THE CLEOPATRA NECKLACE

It doesn’t pay to advertise – always. At least that was the conclusion of the trustees of the great Cosmopolitan Museum after the antiquarians of the country were thrown into a state of hysteria over the strange disappearance of the Cleopatra necklace. The sensational business started with a newspaper paragraph in the Clarion, reading something like this:

‘The trustees of the Cosmopolitan Museum have added to the collection of curios in Egyptian Hall a rare old necklace which they say belonged, beyond the shadow of a doubt, to the famous sorceress of the Nile. As a relic of the civilization which existed three thousand years before Christ, the collar is naturally priceless. Its intrinsic value is placed at $30,000.’

The announcement brought a crush of visitors to Egyptian Hall. The curator, Dr Randall-Brown, had provided a strong plate glass case for the precious relic, and had given it the place of honor in the very center of the marble-tiled hall. The collar of the late – very late – Queen of Egypt reposed on a velvet-covered stand which displayed its rare qualities to excellent advantage. The setting was of some curious metal that was neither gold nor silver, but the necklace itself was a collection of amethysts, pearls and diamonds.

Egyptian Hall was one of a number of large rooms in the Cosmopolitan Museum, which was part of the educational system of the famous University where some eighteen hundred young men, from all parts of the world, were preparing themselves for their attack on the world. The Cosmopolitan Museum, it might be added, was regarded as burglar-proof, as well as fire-proof. One watchman was employed during the day and another by night. George Young, the day watchman, also acted as a sort of guide, and when the trouble came he admitted that he had not remained in Egyptian Hall continuously; that, at one time, he had been out of the room for fifteen minutes.

It was Dr Randall-Brown, the curator, who first made the astonishing discovery. He had brought a connoisseur from Harvard to look at the treasure.

‘You will notice,’ said the curator, gloating over the prize as only an antiquarian can, ‘that there are three pearls, three amethysts and three diamonds in succession, and after that they come in twos and then in ones.’

But even as he spoke, he realized that this orderly arrangement no longer existed. One of the amethysts had been misplaced. Filled with the gloomiest forebodings, he examined the outside of the case. Casually, all seemed well, but the use of a magnifying glass proved that the twelve screws which fastened the case to the flat table, on which it reposed, had been disturbed.

‘Close the doors,’ cried the curator, nervously, ‘and we’ll look into this business.’

The case was opened and the astounding discovery was made that someone had taken the stones from the priceless Cleopatra necklace and had substituted paste diamonds and imitation gems in their place.

The news, which leaked out in spite of the caution of the trustees, made a tremendous sensation. The telegraph and the cable were called into requisition to beseech the police everywhere, and the learned men of the world, to join in the search for the missing treasure. Dealers in precious stones and pawnbrokers were given the description of the gems taken from the necklace, with instructions to arrest the first person who offered such stones for sale. Their curious size and shape, it was added, would make their identification comparatively easy.

The local police made a determined effort to locate the stolen property and to unravel the mystery of the robbery. Everyone connected with the museum, in any capacity whatever, was subjected to a rigid inquiry but without result. The curator and the trustees wrung their hands in despair. They were estimable gentlemen, but their brows were so high and their intellects so keen that they were absolutely helpless in solving everyday problems of life. The University was becoming the laughing stock of the world. It was inconceivable, said outsiders, that such a crime could be committed without the police speedily detecting the criminal.

It was at this stage of the game that Barnes, going into the Clarion office, met his friend Curley, of that paper, and was given this command: ‘Solve the museum mystery.’ He had been given many difficult orders in the past, but this seemed the most impossible of all. Perhaps they were trying to have some fun with him at the office. ‘If so,’ he said to himself, ‘I’ll put the laugh on the other side.’

That afternoon he called up Dr Randall-Brown and told him that he had been commissioned to solve the mystery. The learned curator smiled through his perplexity and said fervently:

‘Do so, and you’ll win my everlasting gratitude.’

‘But,’ insisted Barnes, ‘I must have your authority to cross-examine the employees and to conduct the investigation in any way I see fit.’

‘You have all that,’ replied the doctor. ‘I’ll see that no obstacles are placed in your way.’

The first thing that Barnes considered was the substitution of the fake necklace for the real one in the day time. He interrogated George Young, the day watchman, at some length, and that officer persisted in his statement that his longest length of absence from Egyptian Hall was for fifteen minutes.

‘Didn’t you go out for luncheon?’

‘No, sir; I carried it with me as usual and ate it at that little desk over in the corner of the room, where I had a full view of the case containing the relic.’

‘Have you had many visitors?’

‘Yes, sir; especially since the necklace came.’

‘How many at one time?’

‘The number varied. Sometimes the room was crowded, and again there would be only two or three.’

The detective reflected that it might have been possible for a trained gang of thieves to do the job in fifteen minutes. One man might have stood guard at the door while a half-dozen confederates unscrewed the case and made the substitution. But, of course, they would be subjected to interruption. Altogether, Barnes felt rather skeptical about his theory.

His next move was to put Adam Markley, the night watchman, through the third degree. The results were far from satisfactory, Adam Markley had been with the museum for fifteen years, and his reputation for integrity was very high. Indeed, he almost took a childish interest in the rare objects that were in his charge. He was an illiterate man, but what he lacked in education he supplied with enthusiasm and devotion to duty.

Dr Randall-Brown shook his head smilingly when Barnes spoke of the night watchman.

‘It’s all right to put him on the griddle,’ he said, ‘but you might as well suspect me as old Adam Markley.’

‘I do suspect you,’ began the detective.

The venerable Egyptologist gave a start of surprise. He spoke sharply:

‘Well of all the cheeky –’

Barnes lifted an interrupting hand.

‘I suspect you and everyone connected with this place,’ he finished. ‘You know,’ he added, ‘I am working on the French principle that you’re all guilty until you prove your innocence.’

‘Ah,’ was the relieved reply, ‘that’s different, but I’m sure you’re wasting your time on the night watchman.’

Adam Markley told his story in a straightforward way, and although he was called upon to repeat it, he never once deviated from any of the essential details. He was cherubic in appearance, and in spite of his years, his cheeks were round and rosy, and his blue eyes looked out at his inquisitor with child-like innocence and freshness. He constantly ran his hand through his brown hair, and his manner seemed to say, ‘Why don’t you look for the thief instead of bothering with me?’

Barnes, not content with examining the employees, made an exhaustive investigation into their antecedents. He paid particular attention to the two watchmen. Young, he found, was a married man with a large family living in a modest house in the suburbs. Markley resided in bachelor apartments in the city, living comfortably but inexpensively. Those who knew him were loud in his praise. Some of his older friends recalled him as a child. He had a brother, and the two of them, with long brown curls and rosy cheeks, went about hand in hand like two babes in the wood. The brother, who, unfortunately, had left the straight and narrow path, was now living in the West.

Adam Markley, in the course of his examination, let fall one remark which Barnes thought might develop into a clue. He said that Professor von Hermann had paid five or six visits to the museum and had stood before the case containing the necklace like a man fascinated. Professor von Hermann was one of the world’s greatest archaeologists, and there is no doubt that he keenly felt the disappointment which comes to such a man when a rival – even though that rival be an institution – secures the prize he covets. Barnes, in the course of his investigation, learned that the professor, on one occasion, had told a friend that the only thing he needed to complete his own collection was just such a necklace as the trustees of the Cosmopolitan Museum had fondly believed to be safe in Egyptian Hall. Barnes called at the professor’s home with the idea of gaining some impressions of the venerable connoisseur, but that gentleman bluntly informed him through a servant that he ‘had no time to give to gossiping detectives.’

Barnes relished this greatly, and made a mental resolution to remember the eccentricity – or worse – of the savant at the proper time and place. In the meantime he called upon the curator of the museum for the purpose of asking some further questions.

‘Well, my man,’ cried Dr Randall-Brown, with wet-blanket cordiality, ‘I suppose you’ve come to tell me you’re stumped.’

‘Nothing of the kind,’ protested the detective.

‘You haven’t found the thief?’

‘No,’ admitted Barnes, ‘not yet, but I’ve got a bully good theory.’

‘What is it?’

‘I’m not ready to give it out. What I want to know from you is whether you haven’t forgotten to tell me something.’

‘Sir!’ exclaimed the doctor, with a rising and highly indignant inflection, ‘I’ve told you all I know.’

‘You were in your office in this building the day before the theft was discovered? ‘

‘I was.’

‘Did anything unusual occur?’

‘No, sir.’

‘You stepped out of your office for a few minutes?’

‘Yes, I was in and out several times.’

‘And once, when you returned, you found a young man fumbling in the drawer of your desk?’

The curator’s face lengthened.

‘You’re right, Barnes, I forgot all about that. It seemed such a trifling matter.’

‘It’s the trifles that count, doctor. Who was the young man?’

‘I never learned. He ran out as I came in. I imagine it was one of the students from the University.’

‘Wasn’t he dark-complexioned?’

‘Now that you mention it, I believe that he was.’

‘Haven’t they some Egyptian students in the University?’

‘By Jove, they have five or six. My boy, I believe you’re on the right track!’

Barnes sighed. ‘I doubt it, but I’ve got to clean all of these things up, you know.’

‘Shall I send for the Egyptian students?’

‘No – at least not at present. By the way, do you know Professor von Hermann?’

‘Yes.’

‘Has he ever said anything about the necklace?’

‘Yes, he told me that his collection was incomplete without it and that our collection was incomplete without his Egyptian antiquities. He wondered if the trustees would consider a suggestion to sell him the necklace. I told him the proposition was preposterous.’

‘He thought the collection should be merged?’

‘Exactly, only his plan would be to have the tail wag the dog.’

Six days had now gone and Barnes apparently was no nearer the truth than he had been in the beginning. Every day regularly he reported at the Clarion office and found against his name on the assignment book in the Clarion office the command, ‘Solve the museum mystery.’ The city editor, in his dry mirthless way, did his best to tease the emergency man.

‘If you want to give up the assignment, Barnes,’ he said, ‘I’ll let you report the meetings of the Universal Peace Union.’

‘No,’ said the baited one, clicking his teeth with determination, ‘I’ll finish this job first if you don’t mind.’

That night he enlisted the aid of his friend and fellow worker, Clancy.

‘You needn’t tell me what you want,’ said the loyal Con, ‘I’ll go with you anywhere without asking questions.’

At midnight the two of them were prowling about the dark stone walls of the Cosmopolitan Museum. The place was on the outskirts of the city, and at that hour was lonely and deserted. A dim light shone from one of the small windows near the entrance. It was too high for either of them to look inside.

‘I’d give a dollar for a soap box or something to stand on,’ grunted Barnes.

Clancy never hesitated for an instant.

‘Let’s play horsey,’ he said.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Why, I’ll get down on my hands and knees,’ quoth the faithful one, ‘and you can stand on my back and peep inside.’

It was no sooner said than done. The improvised stand proved to be just the right height.

By clutching the window sill with his fingertips Barnes was able to draw himself up and peer into the little room that led to the museum.

There sat old Markley tilted back in a chair with his feet on the window ledge reading a book. A half smile wreathed his cherubic face, and he had the appearance of a man who, as one of our Presidents once remarked, was ‘at peace with the world and the rest of mankind.’

There was certainly nothing to excite suspicion in appearance or the action of the venerable person, and yet the mere sight of him seemed to throw Barnes into a state of intense excitement

‘I’ve got it! I’ve got it!’ he whispered hoarsely to his friend, as he jumped from Clancy’s willing back.

‘Got what?’

‘Never mind,’ was the impatient retort as he grabbed his associate by the coat sleeve, ‘come with me.’

‘What are you going to do now?’ ventured Clancy.

‘Commit burglary, I hope,’ ejaculated Barnes fervently.

Clancy looked at Barnes with real concern. He wondered whether he could, by any possibility, be taking leave of his senses. In spite of this momentary doubt he followed his friend with the blind devotion which was his most becoming trait. Soon after leaving the museum they were able to get a cab and in a little while the vehicle, pursuant to Barnes’s directions, drew up in front of Adam Markley’s lodgings.

‘This is the part of the job that I dislike, but desperate cases require desperate methods.’

‘How in the world can you get in?’

‘This is one feature of the case where credit belongs to the police department. They secured skeleton keys in order to search old Markley’s rooms.’

‘Then what’s the use of your doing it over again?’

‘Oh, they might have forgotten something,’ was the laughing rejoinder.

The two men entered the house noiselessly, crept silently up the stairs and soon found themselves in the modest habitation of the old watchman. It consisted of a bedroom and a sitting room. Barnes paid no attention to the sleeping chamber, but proceeded at once to the living apartment. This was plainly but comfortably furnished. A roll-top desk stood in one comer and a big Morris chair in the other. The left wall contained some family photographs, and Barnes gazed long and earnestly at one of these representing two young men. The other wall held a large engraving of General Grant on horseback. Presently Barnes went to the desk. It was locked. Without any evidence of compunction he pulled out a sharp instrument and began to twist the lock.

‘You’re going pretty far,’ said Clancy gravely.

‘Yes,’ retorted the irrepressible one, ‘and the farther I go the more I learn.’

The lock yielded and the top rolled up. Barnes grabbed a handful of papers and went through them like a conjurer doing a trick. Finally he reached a little yellow slip. He read what was written on the sheet and gave a gurgle of delight. He hastily slipped all the papers back in place and pulled the desk down in a way that automatically locked it, and cried out cheerfully:

‘We’re through, Clancy, old boy; nothing to do until tomorrow.’

After breakfast next day Barnes called Dayton, Ohio, on the long-distance telephone. It took him some time to get the person he wanted, but by noon his face was wreathed in smiles.

‘It’s all right,’ he exclaimed gaily to Clancy, ‘I want you to meet me at Markley’s room the day after tomorrow at eight o’clock in the morning.’

‘Why?’

‘Oh, we’re going to have a little surprise party.’

At the hour appointed Barnes and Clancy were at the modest quarters of the old watchman. So was Dr Randall-Brown. The curator was annoyed.

‘I don’t like this,’ he exclaimed testily. ‘I don’t relish the idea of breaking into a man’s rooms without absolute proof.’

Barnes smiled.

‘If we had absolute proof, we wouldn’t have to do it.’

‘Well, what do you expect to prove by coming here?’

‘That depends entirely on the result of my experiment. We’ll know all about it in a few minutes.’

As he spoke, heavy footsteps were heard on the stairway, and in a few minutes Markley entered the room. He seemed dazed at the unexpected sight of strangers in his apartments.

‘What’s – what’s the meaning of this?’ he stammered.

‘You know,’ said Barnes, sharply.

‘I don’t,’ he retorted with a trace of defiance.

Barnes advanced until he stood directly in front of the old man. He pointed an accusing finger at him. He spoke sternly.

‘I charge you with the theft of the Cleopatra necklace from the Cosmopolitan Museum!’

The color slowly receded from the cheeks of the man’s cherubic face. He sank weakly into the easy chair. It was some moments before he spoke, and then it was in a hushed and trembling voice.