Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

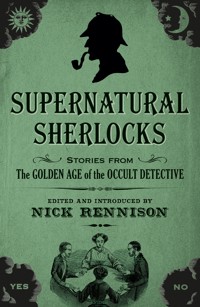

The ghost of a poor Afghan returns to haunt the doctor who once amputated his hand. A mysterious and malignant force inhabits a room in an ancestral home and attacks all who sleep in it. A man who desecrates an Indian temple is transformed into a ravening beast. A Tyrolean castle is the setting for an aristocratic murderer's apparent resurrection. In the stories in this collection compiled by Nick Rennison, horrors from beyond the grave and other dimensions visit the everyday world and demand to be investigated. The Sherlocks of the supernatural - from William Hope Hodgson's 'Thomas Carnacki, the Ghost Finder', to Alice and Claude Askew's 'Aylmer Vance' - are those courageous souls who risk their lives and their sanity to pursue the truth about ghosts, ghouls and things that go bump in the night. The period between 1890 and 1930 was a Golden Age for the occult detective. Famous authors like Kipling and Conan Doyle wrote stories about them, as did less familiar writers such as the occultist and magician Dion Fortune and Henry S. Whitehead, a friend of HP Lovecraft and fellow-contributor to the pulp magazines of the period. Nick Rennison, editor of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes and The Rivals of Dracula, has chosen fifteen tales from that era to raise the hair and chill the spines of modern readers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 517

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUPERNATURAL SHERLOCKS

The ghost of a poor Afghan returns to haunt the doctor who once amputated his hand. A mysterious and malignant force inhabits a room in an ancestral home and attacks all who sleep in it. A man who desecrates an Indian temple is transformed into a ravening beast. A castle in the Tyrol is the setting for an aristocratic murderer’s apparent resurrection.

In the stories in this collection, horrors from beyond the grave and from other dimensions visit the everyday world and demand to be investigated. The Sherlocks of the supernatural – from William Hope Hodgson’s ‘Thomas Carnacki, the Ghost Finder’, to Alice and Claude Askew’s ‘Aylmer Vance’ – are those courageous souls who risk their lives and their sanity to pursue the truth about ghosts, ghouls and things that go bump in the night.

The period between 1890 and 1930 was a Golden Age for the occult detective. Famous authors like Kipling and Conan Doyle wrote stories about them, as did less familiar writers such as the occultist and magician Dion Fortune and Henry S Whitehead, a friend of HP Lovecraft and fellow-contributor to the pulp magazines of the period. Nick Rennison, editor of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes and The Rivals of Dracula, has chosen fifteen tales from that era to raise the hair and chill the spines of modern readers.

About the author

Nick Rennison is a writer, editor and bookseller. He has published books on a wide variety of subjects from Sherlock Holmes to London’s blue plaques. He is a regular reviewer for the Sunday Times and for BBC History Magazine. His titles for Pocket Essentials include Sigmund Freud, Peter MarkRoget: The Man Who Became a Book, Robin Hood: Myth, History & Culture and A Short History of Polar Exploration. He has edited two previous collections of short stories for No Exit Press, The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes and The Rivals of Dracula. He lives near Manchester.

INTRODUCTION

What exactly is an occult detective? In the most basic definition, an occult detective is a fictional character who investigates mysteries of the supernatural rather than the natural world. Such psychic sleuths have been familiar figures in popular literature since the nineteenth century. The origins of what I have chosen to call ‘Supernatural Sherlocks’ lie outside the time parameters of this anthology. Before the 1880s there were characters who can retrospectively be described as occult detectives. As early as the 1830s, the Welsh lawyer, MP and novelist Samuel Warren published a series of tales in Blackwoods Magazine narrated by a doctor whose case files involve most of the standard themes of Gothic literature from lunacy and alcoholism to ghosts and grave robbing. The best of Warren’s stories mix the occult and the macabre into a satisfyingly lurid brew. They were very popular in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, both in Britain and in America, where Edgar Allan Poe read them, although he did dismiss them as ‘shamefully ill-written’. Fitz-James O’Brien, an Irish writer who emigrated from his native land to the United States in the 1850s and was killed in the American Civil War, wrote a large number of fantastical and weird stories in his short literary career. Two of them (‘The Pot of Tulips’ and ‘What Was It? A Mystery’) feature a character named Harry Escott who uses the skills of a detective to unravel supernatural mysteries. Dr Martin Hesselius, who appears in Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella ‘Green Tea’ and acts as a framing narrator for the other stories in the 1872 volume In a Glass Darkly, is another pioneering supernatural investigator.

However, it was at the end of the nineteenth century, that the occult detective really came into his (or her) own. These were the years in which Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes short stories were first published and became so astonishingly successful that they inspired innumerable imitators. They were also years which saw a flourishing interest in the supernatural. Mediums such as Daniel Douglas Home, renowned for his supposed ability to levitate and to communicate with the dead, were famous figures, celebrated in newspapers and magazines, and lionised by high society. The Society for Psychical Research, the first organisation of its kind in the world, was founded in London in 1882. It was not some grouping from the lunatic fringe, populated exclusively by eccentrics and the barely sane. Its founders included leading scientists and academics of the day. Its first president was the Cambridge philosopher and economist Henry Sidgwick and early members included the chemist William Crookes, the physicist Oliver Lodge and the American psychologist William James, older brother of the novelist Henry James.

The growth in interest in the scientific investigation of the supernatural and paranormal was matched by an increasing fascination for ghost stories. Tales of ghosts and hauntings have, of course, been around as long as men, women and children have gathered around a fireside to cheer their spirits and keep the darkness at bay. All cultures have examples of them. Spirits of the dead can be found in the Bible and in the works of Homer. They exist in Japanese literature, in the mediaeval Arabic stories of the One Thousand and One Nights and in the drama of Renaissance Europe. Ghouls and ghosts flourished in the Gothic fiction of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Edgar Allan Poe and Sheridan Le Fanu picked up themes from Gothic fiction and developed them in their stories. Dickens spotted the commercial potential in ghost stories and began to produce his own examples, most famously A Christmas Carol. However, the ‘Golden Age’ of the ghost story began in the last decades of the nineteenth century when writers began to fill the pages of the periodical press with tales of haunted houses and spectral visitors from another world.

In the 1890s a new sub-genre emerged from the mass of fiction that was produced for this magazine market. It mingled elements of the detective story, as newly popularised by Conan Doyle, and the ghost story. The occult detective – in the sense of someone who was a specialised investigator of supernatural mysteries – was born. Arabella Kenealy’s character Lord Syfret, who first appeared in stories published in Ludgate Magazine in 1896, had some of the characteristics of an occult detective but it is generally agreed that the first fully-fledged occult detective was Flaxman Low. Low was created by the mother-and-son writing team of Kate and Hesketh Prichard, working under the pseudonyms of E and H Heron, and made his bow in a series of stories published in Pearson’s Magazine in 1898. These were then collected the following year in a volume entitled Ghosts: Being the Experiences of Flaxman Low. The Prichards’ character, like so many others of the period, owed much to Sherlock Holmes but he had his own originality. Many more followed in his footsteps.

Over the next two decades, a regiment of occult detectives lined up to do battle with the forces of darkness. John Silence, ‘physician extraordinary’ as the subtitle of a 1908 collection of stories described him, was the creation of Algernon Blackwood, one of the twentieth century’s most gifted authors of supernatural fiction. (Blackwood had earlier created a character named Jim Shorthouse who appeared in four short stories and had some of the attributes of an occult detective.) LT Meade and Robert Eustace’s Diana Marburg was a clairvoyant who investigated crimes and mysteries. The prolific pulp fiction writer Victor Rousseau, using the pseudonym HM Egbert, published a dozen short stories in various American newspapers in 1910 (reprinted in the 1920s in the legendary pulp magazine Weird Tales) which featured an investigator of supernatural mysteries named Dr Ivan Brodsky.

Many of these occult detectives, like their counterparts in standard detective fiction, had particular gifts or qualities which contributed to their investigative successes. Harold Begbie’s Andrew Latter, who appeared in six short stories published in London Magazine in 1904, had the ability to enter a dream-world, moving through it to access information hidden from others. Alice and Claude Askew’s Aylmer Vance, with his Dr Watson-like sidekick Dexter, who appeared in stories published in a magazine called The Weekly Tale-Teller in 1914, was the most obviously Sherlockian of the occult detectives. Perhaps the most famous of these pre-First World War psychic sleuths was Carnacki the Ghost Finder, hero of stories by William Hope Hodgson which were published mostly in The Idler in 1910 and collected into book form three years later. More than any other occult detective of the period, Carnacki has become a recurring figure in popular culture. Contemporary writers have written new Carnacki stories and the ghost finder is a member of the ‘League of Extraordinary Gentlemen’ in Alan Moore’s graphic novel of that name.

Writers who have proved much more famous for other work also wrote occult detective stories. Under his pen-name of Sax Rohmer, Arthur Ward invented the oriental criminal mastermind Fu Manchu but he was also the creator in 1913 of Moris Klaw, a clairvoyant detective who dreamt the solutions to weird mysteries. During the First World War, Aleister Crowley, the occultist and practising magician who was later dubbed the ‘Wickedest Man in the World’, was forced by poverty to turn his hand to writing fiction. His stories of a philosopher-cum-mystic-cum-psychic detective named Simon Iff were first published in a magazine in 1917 and have recently been collected in book form.

The First World War, with its appalling toll of young lives, stimulated interest in ideas of life beyond the grave. So many men had died and those who had loved them sought reasons for their losses. Many looked for reassurance that the souls of the dead lived on. Traditional religions could not always provide the comfort required and spiritualism and other alternative belief systems flourished. In this context, stories of the supernatural in general – and of supernatural investigators in particular – continued to find a wide readership. Many of the new writers of occult detective stories in the 1920s were women. The actress and author Ella Scrymsour published a series of tales about Shiela Crerar, a young Scotswoman with psychic abilities. The impressively named Rose Champion de Crespigny created an occult detective called Norton Vyse and Jessie Douglas Kerruish published a still readable novel entitled The Undying Monster, made into a Hollywood horror movie in the 1940s, which featured Luna Bartendale, a woman of many psychic abilities, and her investigations into an outbreak of werewolfism. However, the best known of these female writers was Dion Fortune. Fortune is still a familiar name on the New Age shelves of British bookshops and her works of occult and magical philosophy, with titles like The Cosmic Doctrine and Moon Magic, still find a readership seventy years after her death. In the 1920s, she also published a series of enjoyable stories about a multi-talented psychic sleuth and healer called Dr John Taverner.

Fortune was able to find a place for her Taverner stories in the traditional periodical press (they appeared in Royal Magazine) but this market for writers of the supernatural, so flourishing in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, now began its slow decline. In contrast, the pulp magazine grew in popularity, particularly in America. From the 1920s onward, the occult detective was more likely to be found in the pages of Weird Tales than in, say, Pearson’s Magazine or The Strand Magazine. An ideal example is Henry S Whitehead’s Gerald Canevin, one of whose adventures I have included in this anthology. In many ways, Whitehead was quite a sophisticated writer and his prose would not have seemed out of place in the more upmarket magazines. Perhaps, had he been publishing twenty years earlier, that is where it would have been found. As it was, his Canevin stories all appeared in the pulps, mostly in Weird Tales.

In the decades since 1930, the year which I have chosen as the cut-off point for this anthology of stories from the ‘Golden Age’ of the occult detective, the psychic sleuth has continued to thrive. The American pulp writer Seabury Quinn created Jules de Grandin, an expert on the supernatural and former member of the French Sûreté, in 1925. Over the next quarter of a century, de Grandin appeared in more than ninety stories, mostly published in Weird Tales, in which he confronted a wide variety of ghosts, ghouls and things that go bump in the night. Weird Tales was also the first home of Manly Wade Wellman’s creation John Thunstone, a wealthy scholar and occultist who battles assorted supernatural creatures.

Thunstone appeared in stories throughout the 1940s and, late in his career, Wade Wellman published two novels featuring the character. In the sixties, Joseph Payne Brennan introduced readers of the Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine to his occult detective Lucius Leffing who went on to appear in more than forty stories, many of them collected into hardback volumes.

Throughout the twentieth century, the occult detective has appeared not only in the traditional print media but in other media as well. In the 1930s and 1940s, radio had ‘The Shadow’ (briefly voiced by Orson Welles) and ‘The Mysterious Traveller’, both enigmatic narrators of often supernatural tales. TV has had its share of psychic investigators from ‘Kolchak the Night Stalker’ to Sam and Dean Winchester in Supernatural. What else are Mulder and Scully in The X-Files but occult detectives? Films such as Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (based on a novel by William Hjörstberg) owe something to the tradition. And Ghostbusters, both in its 1980s and its 2016 incarnations, basically follows the activities of a gang of occult investigators, although ones with more sophisticated technology to call upon than Carnacki the Ghost Finder ever had. The occult detective has become a familiar figure in comics and graphic novels from The Occult Files of Dr. Spektor to Hellblazer. In the twenty-first century, although practitioners in print like Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden continue to flourish, it may well be in films, TV shows and games that the occult detective’s future mostly lies.

It should always be remembered, however, that the figure has a long history. In this volume, I have covered fifty years of that history. I have tried to bring together all kinds of stories from the ‘Golden Age’ of the occult detective. The anthology begins with tales (including ones by Rudyard Kipling and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) which feature amateur investigators drawn by curiosity to look into paranormal phenomena. It moves on to include examples of the adventures of those like Flaxman Low, Thomas Carnacki and Aylmer Vance who were created as professional or semi-professional investigators of the supernatural. I have also chosen stories about intrepid souls who undertake one-off inquiries into haunted houses. They too deserve to be called ‘Supernatural Sherlocks’. The result, I hope, is a collection of classic tales which can still raise the hair and chill the spines of modern readers.

THE MARK OF THE BEAST (1890)

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

When, in 1907, Kipling became the first English-language writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Swedish Academy which awarded the prize called him ‘the greatest genius in the realm of narrative that his country has produced in our times’. This genius showed itself as much, if not more, in short stories as in longer works of fiction like Kim. In common with other writers of the late Victorian era, Kipling was fascinated by the weird and the supernatural, and a number of his stories demonstrate that. In two of these, this one and ‘The Return of Imray’, his character Strickland (who also appears in other non-supernatural tales) investigates occult mysteries. ‘The Mark of the Beast’ first appeared in The Pioneer, the English language newspaper in India for which Kipling had worked until leaving for London in 1889. It was later included in his collection of short stories entitled Life’s Handicap. Its power lies as much in what is left unsaid as in what is bluntly stated. Kipling deliberately withholds information about exactly what happens. Partly this is because of the sensitivities of the age (‘Several other things happened also, but they cannot be put down here’) but mostly it is a deliberate strategy designed to leave a space in which the reader’s imagination can go to work. When it was first published, ‘The Mark of the Beast’ was severely criticised. A reviewer in The Spectator called it ‘curious but… loathsome’. Today we might be more concerned about its depiction of the Indian leper and his treatment than anything else but it remains a striking story.

Your Gods and my Gods – do you or I know which are the stronger?

Native Proverb

EAST of Suez, some hold, the direct control of Providence ceases; Man being there handed over to the power of the Gods and Devils of Asia, and the Church of England Providence only exercising an occasional and modified supervision in the case of Englishmen.

This theory accounts for some of the more unnecessary horrors of life in India: it may be stretched to explain my story.

My friend Strickland of the Police, who knows as much of natives of India as is good for any man, can bear witness to the facts of the case. Dumoise, our doctor, also saw what Strickland and I saw. The inference which he drew from the evidence was entirely incorrect. He is dead now; he died, in a rather curious manner, which has been elsewhere described.

When Fleete came to India he owned a little money and some land in the Himalayas, near a place called Dharmsala. Both properties had been left him by an uncle, and he came out to finance them. He was a big, heavy, genial, and inoffensive man. His knowledge of natives was, of course, limited, and he complained of the difficulties of the language.

He rode in from his place in the hills to spend New Year in the station, and he stayed with Strickland. On New Year’s Eve there was a big dinner at the club, and the night was excusably wet. When men foregather from the uttermost ends of the Empire, they have a right to be riotous. The Frontier had sent down a contingent o’ Catch-’em-Alive-O’s who had not seen twenty white faces for a year, and were used to ride fifteen miles to dinner at the next Fort at the risk of a Khyberee bullet where their drinks should lie. They profited by their new security, for they tried to play pool with a curled-up hedgehog found in the garden, and one of them carried the marker round the room in his teeth. Half a dozen planters had come in from the south and were talking ‘horse’ to the Biggest Liar in Asia, who was trying to cap all their stories at once. Everybody was there, and there was a general closing up of ranks and taking stock of our losses in dead or disabled that had fallen during the past year. It was a very wet night, and I remember that we sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’ with our feet in the Polo Championship Cup, and our heads among the stars, and swore that we were all dear friends. Then some of us went away and annexed Burma, and some tried to open up the Soudan and were opened up by Fuzzies in that cruel scrub outside Suakim, and some found stars and medals, and some were married, which was bad, and some did other things which were worse, and the others of us stayed in our chains and strove to make money on insufficient experiences.

Fleete began the night with sherry and bitters, drank champagne steadily up to dessert, then raw, rasping Capri with all the strength of whisky, took Benedictine with his coffee, four or five whiskies and sodas to improve his pool strokes, beer and bones at half-past two, winding up with old brandy. Consequently, when he came out, at half-past three in the morning, into fourteen degrees of frost, he was very angry with his horse for coughing, and tried to leapfrog into the saddle. The horse broke away and went to his stables; so Strickland and I formed a Guard of Dishonour to take Fleete home.

Our road lay through the bazaar, close to a little temple of Hanuman, the Monkey-god, who is a leading divinity worthy of respect. All gods have good points, just as have all priests. Personally, I attach much importance to Hanuman, and am kind to his people – the great grey apes of the hills. One never knows when one may want a friend.

There was a light in the temple, and as we passed, we could hear voices of men chanting hymns. In a native temple, the priests rise at all hours of the night to do honour to their god. Before we could stop him, Fleete dashed up the steps, patted two priests on the back, and was gravely grinding the ashes of his cigar-butt into the forehead of the red stone image of Hanuman. Strickland tried to drag him out, but he sat down and said solemnly:

‘Shee that? Mark of the B-beasht!Imade it. Ishn’t it fine?’

In half a minute the temple was alive and noisy, and Strickland, who knew what came of polluting gods, said that things might occur. He, by virtue of his official position, long residence in the country, and weakness for going among the natives, was known to the priests and he felt unhappy. Fleete sat on the ground and refused to move. He said that ‘good old Hanuman’ made a very soft pillow.

Then, without any warning, a Silver Man came out of a recess behind the image of the god. He was perfectly naked in that bitter, bitter cold, and his body shone like frosted silver, for he was what the Bible calls ‘a leper as white as snow.’ Also he had no face, because he was a leper of some years’ standing and his disease was heavy upon him. We two stooped to haul Fleete up, and the temple was filling and filling with folk who seemed to spring from the earth, when the Silver Man ran in under our arms, making a noise exactly like the mewing of an otter, caught Fleete round the body and dropped his head on Fleete’s breast before we could wrench him away. Then he retired to a corner and sat mewing while the crowd blocked all the doors.

The priests were very angry until the Silver Man touched Fleete. That nuzzling seemed to sober them.

At the end of a few minutes’ silence one of the priests came to Strickland and said, in perfect English, ‘Take your friend away. He has done with Hanuman, but Hanuman has not done with him.’ The crowd gave room and we carried Fleete into the road.

Strickland was very angry. He said that we might all three have been knifed, and that Fleete should thank his stars that he had escaped without injury.

Fleete thanked no one. He said that he wanted to go to bed. He was gorgeously drunk.

We moved on, Strickland silent and wrathful, until Fleete was taken with violent shivering fits and sweating. He said that the smells of the bazaar were overpowering, and he wondered why slaughter-houses were permitted so near English residences. ‘Can’t you smell the blood?’ said Fleete.

We put him to bed at last, just as the dawn was breaking, and Strickland invited me to have another whisky and soda. While we were drinking he talked of the trouble in the temple, and admitted that it baffled him completely. Strickland hates being mystified by natives, because his business in life is to overmatch them with their own weapons. He has not yet succeeded in doing this, but in fifteen or twenty years he will have made some small progress.

‘They should have mauled us,’ he said, ‘instead of mewing at us. I wonder what they meant. I don’t like it one little bit.’

I said that the Managing Committee of the temple would in all probability bring a criminal action against us for insulting their religion. There was a section of the Indian Penal Code which exactly met Fleete’s offence. Strickland said he only hoped and prayed that they would do this. Before I left I looked into Fleete’s room, and saw him lying on his right side, scratching his left breast. Then I went to bed cold, depressed, and unhappy, at seven o’clock in the morning.

At one o’clock I rode over to Strickland’s house to inquire after Fleete’s head. I imagined that it would be a sore one. Fleete was breakfasting and seemed unwell. His temper was gone, for he was abusing the cook for not supplying him with an underdone chop. A man who can eat raw meat after a wet night is a curiosity. I told Fleete this and he laughed.

‘You breed queer mosquitoes in these parts,’ he said. ‘I’ve been bitten to pieces, but only in one place.’

‘Let’s have a look at the bite,’ said Strickland. ‘It may have gone down since this morning.’

While the chops were being cooked, Fleete opened his shirt and showed us, just over his left breast, a mark, the perfect double of the black rosettes – the five or six irregular blotches arranged in a circle – on a leopard’s hide. Strickland looked and said, ‘It was only pink this morning. It’s grown black now.’

Fleete ran to a glass.

‘By Jove!’ he said, ‘this is nasty. What is it?’

We could not answer. Here the chops came in, all red and juicy, and Fleete bolted three in a most offensive manner. He ate on his right grinders only, and threw his head over his right shoulder as he snapped the meat. When he had finished, it struck him that he had been behaving strangely, for he said apologetically, ‘I don’t think I ever felt so hungry in my life. I’ve bolted like an ostrich.’

After breakfast Strickland said to me, ‘Don’t go. Stay here, and stay for the night.’

Seeing that my house was not three miles from Strickland’s, this request was absurd. But Strickland insisted, and was going to say something when Fleete interrupted by declaring in a shamefaced way that he felt hungry again. Strickland sent a man to my house to fetch over my bedding and a horse, and we three went down to Strickland’s stables to pass the hours until it was time to go out for a ride. The man who has a weakness for horses never wearies of inspecting them; and when two men are killing time in this way they gather knowledge and lies the one from the other.

There were five horses in the stables, and I shall never forget the scene as we tried to look them over. They seemed to have gone mad. They reared and screamed and nearly tore up their pickets; they sweated and shivered and lathered and were distraught with fear. Strickland’s horses used to know him as well as his dogs; which made the matter more curious. We left the stable for fear of the brutes throwing themselves in their panic. Then Strickland turned back and called me. The horses were still frightened, but they let us ‘gentle’ and make much of them, and put their heads in our bosoms.

‘They aren’t afraid of us,’ said Strickland. ‘D’you know, I’d give three months’ pay if Outrage here could talk.’

But Outrage was dumb, and could only cuddle up to his master and blow out his nostrils, as is the custom of horses when they wish to explain things but can’t. Fleete came up when we were in the stalls, and as soon as the horses saw him, their fright broke out afresh. It was all that we could do to escape from the place unkicked. Strickland said, ‘They don’t seem to love you, Fleete.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Fleete; ‘my mare will follow me like a dog.’ He went to her; she was in a loose-box; but as he slipped the bars she plunged, knocked him down, and broke away into the garden. I laughed, but Strickland was not amused. He took his moustache in both fists and pulled at it till it nearly came out. Fleete, instead of going off to chase his property, yawned, saying that he felt sleepy. He went to the house to lie down, which was a foolish way of spending New Year’s Day.

Strickland sat with me in the stables and asked if I had noticed anything peculiar in Fleete’s manner. I said that he ate his food like a beast; but that this might have been the result of living alone in the hills out of the reach of society as refined and elevating as ours for instance. Strickland was not amused. I do not think that he listened to me, for his next sentence referred to the mark on Fleete’s breast, and I said that it might have been caused by blister-flies, or that it was possibly a birth-mark newly born and now visible for the first time. We both agreed that it was unpleasant to look at, and Strickland found occasion to say that I was a fool.

‘I can’t tell you what I think now,’ said he, ‘because you would call me a madman; but you must stay with me for the next few days, if you can. I want you to watch Fleete, but don’t tell me what you think till I have made up my mind.’

‘But I am dining out to-night,’ I said.

‘So am I,’ said Strickland, ‘and so is Fleete. At least if he doesn’t change his mind.’

We walked about the garden smoking, but saying nothing – because we were friends, and talking spoils good tobacco – till our pipes were out. Then we went to wake up Fleete. He was wide awake and fidgeting about his room.

‘I say, I want some more chops,’ he said. ‘Can I get them?’

We laughed and said, ‘Go and change. The ponies will be round in a minute.’

‘All right,’ said Fleete. ‘I’ll go when I get the chops – underdone ones, mind.’

He seemed to be quite in earnest. It was four o’clock, and we had had breakfast at one; still, for a long time, he demanded those underdone chops. Then he changed into riding clothes and went out into the verandah. His pony – the mare had not been caught – would not let him come near. All three horses were unmanageable – mad with fear – and finally Fleete said that he would stay at home and get something to eat. Strickland and I rode out wondering. As we passed the temple of Hanuman, the Silver Man came out and mewed at us.

‘He is not one of the regular priests of the temple,’ said Strickland. ‘I think I should peculiarly like to lay my hands on him.’

There was no spring in our gallop on the racecourse that evening. The horses were stale, and moved as though they had been ridden out.

‘The fright after breakfast has been too much for them,’ said Strickland.

That was the only remark he made through the remainder of the ride. Once or twice I think he swore to himself; but that did not count.

We came back in the dark at seven o’clock, and saw that there were no lights in the bungalow. ‘Careless ruffians my servants are!’ said Strickland.

My horse reared at something on the carriage drive, and Fleete stood up under its nose.

‘What are you doing, grovelling about the garden?’ said Strickland.

But both horses bolted and nearly threw us. We dismounted by the stables and returned to Fleete, who was on his hands and knees under the orange-bushes.

‘What the devil’s wrong with you?’ said Strickland.

‘Nothing, nothing in the world,’ said Fleete, speaking very quickly and thickly. ‘I’ve been gardening – botanising you know. The smell of the earth is delightful. I think I’m going for a walk – a long walk – all night.’

Then I saw that there was something excessively out of order somewhere, and I said to Strickland, ‘I am not dining out.’

‘Bless you!’ said Strickland. ‘Here, Fleete, get up. You’ll catch fever there. Come in to dinner and let’s have the lamps lit. We’ll all dine at home.’

Fleete stood up unwillingly, and said, ‘No lamps – no lamps. It’s much nicer here. Let’s dine outside and have some more chops – lots of ’em and underdone – bloody ones with gristle.’

Now a December evening in Northern India is bitterly cold, and Fleete’s suggestion was that of a maniac.

‘Come in,’ said Strickland sternly. ‘Come in at once.’

Fleete came, and when the lamps were brought, we saw that he was literally plastered with dirt from head to foot. He must have been rolling in the garden. He shrank from the light and went to his room. His eyes were horrible to look at. There was a green light behind them, not in them, if you understand, and the man’s lower lip hung down.

Strickland said, ‘There is going to be trouble – big trouble – to-night. Don’t you change your riding-things.’

We waited and waited for Fleete’s reappearance, and ordered dinner in the meantime. We could hear him moving about his own room, but there was no light there. Presently from the room came the long-drawn howl of a wolf.

People write and talk lightly of blood running cold and hair standing up and things of that kind. Both sensations are too horrible to be trifled with. My heart stopped as though a knife had been driven through it, and Strickland turned as white as the tablecloth.

The howl was repeated, and was answered by another howl far across the fields.

That set the gilded roof on the horror. Strickland dashed into Fleete’s room. I followed, and we saw Fleete getting out of the window. He made beast-noises in the back of his throat. He could not answer us when we shouted at him. He spat.

I don’t quite remember what followed, but I think that Strickland must have stunned him with the long boot-jack or else I should never have been able to sit on his chest. Fleete could not speak, he could only snarl, and his snarls were those of a wolf, not of a man. The human spirit must have been giving way all day and have died out with the twilight. We were dealing with a beast that had once been Fleete.

The affair was beyond any human and rational experience. I tried to say ‘Hydrophobia’, but the word wouldn’t come, because I knew that I was lying.

We bound this beast with leather thongs of the punkah-rope, and tied its thumbs and big toes together, and gagged it with a shoe-horn, which makes a very efficient gag if you know how to arrange it. Then we carried it into the dining-room, and sent a man to Dumoise, the doctor, telling him to come over at once. After we had despatched the messenger and were drawing breath, Strickland said, ‘It’s no good. This isn’t any doctor’s work.’ I, also, knew that he spoke the truth.

The beast’s head was free, and it threw it about from side to side. Anyone entering the room would have believed that we were curing a wolf’s pelt. That was the most loathsome accessory of all.

Strickland sat with his chin in the heel of his fist, watching the beast as it wriggled on the ground, but saying nothing. The shirt had been torn open in the scuffle and showed the black rosette mark on the left breast. It stood out like a blister.

In the silence of the watching we heard something without mewing like a she-otter. We both rose to our feet, and, I answer for myself, not Strickland, felt sick – actually and physically sick. We told each other, as did the men in Pinafore, that it was the cat.

Dumoise arrived, and I never saw a little man so unprofessionally shocked. He said that it was a heart-rending case of hydrophobia, and that nothing could be done. At least any palliative measures would only prolong the agony. The beast was foaming at the mouth. Fleete, as we told Dumoise, had been bitten by dogs once or twice. Any man who keeps half a dozen terriers must expect a nip now and again. Dumoise could offer no help. He could only certify that Fleete was dying of hydrophobia. The beast was then howling, for it had managed to spit out the shoe-horn. Dumoise said that he would be ready to certify to the cause of death, and that the end was certain. He was a good little man, and he offered to remain with us; but Strickland refused the kindness. He did not wish to poison Dumoise’s New Year. He would only ask him not to give the real cause of Fleete’s death to the public.

So Dumoise left, deeply agitated; and as soon as the noise of the cart-wheels had died away, Strickland told me, in a whisper, his suspicions. They were so wildly improbable that he dared not say them out aloud; and I, who entertained all Strickland’s beliefs, was so ashamed of owning to them that I pretended to disbelieve.

‘Even if the Silver Man had bewitched Fleete for polluting the image of Hanuman, the punishment could not have fallen so quickly.’

As I was whispering this the cry outside the house rose again, and the beast fell into a fresh paroxysm of struggling till we were afraid that the thongs that held it would give way.

‘Watch!’ said Strickland. ‘If this happens six times I shall take the law into my own hands. I order you to help me.’

He went into his room and came out in a few minutes with the barrels of an old shot-gun, a piece of fishing-line, some thick cord, and his heavy wooden bedstead. I reported that the convulsions had followed the cry by two seconds in each case, and the beast seemed perceptibly weaker.

Strickland muttered, ‘But he can’t take away the life! He can’t take away the life!’

I said, though I knew that I was arguing against myself, ‘It may be a cat. It must be a cat. If the Silver Man is responsible, why does he dare to come here?’

Strickland arranged the wood on the hearth, put the gun-barrels into the glow of the fire, spread the twine on the table and broke a walking stick in two. There was one yard of fishing line, gut, lapped with wire, such as is used for mahseer-fishing, and he tied the two ends together in a loop.

Then he said, ‘How can we catch him? He must be taken alive and unhurt.’

I said that we must trust in Providence, and go out softly with polo-sticks into the shrubbery at the front of the house. The man or animal that made the cry was evidently moving round the house as regularly as a night-watchman. We could wait in the bushes till he came by and knock him over.

Strickland accepted this suggestion, and we slipped out from a bath-room window into the front verandah and then across the carriage drive into the bushes.

In the moonlight we could see the leper coming round the corner of the house. He was perfectly naked, and from time to time he mewed and stopped to dance with his shadow. It was an unattractive sight, and thinking of poor Fleete, brought to such degradation by so foul a creature, I put away all my doubts and resolved to help Strickland from the heated gun-barrels to the loop of twine – from the loins to the head and back again – with all tortures that might be needful.

The leper halted in the front porch for a moment and we jumped out on him with the sticks. He was wonderfully strong, and we were afraid that he might escape or be fatally injured before we caught him. We had an idea that lepers were frail creatures, but this proved to be incorrect. Strickland knocked his legs from under him and I put my foot on his neck. He mewed hideously, and even through my riding-boots I could feel that his flesh was not the flesh of a clean man.

He struck at us with his hand and feet-stumps. We looped the lash of a dog-whip round him, under the armpits, and dragged him backwards into the hall and so into the dining-room where the beast lay. There we tied him with trunk-straps. He made no attempt to escape, but mewed.

When we confronted him with the beast the scene was beyond description. The beast doubled backwards into a bow as though he had been poisoned with strychnine, and moaned in the most pitiable fashion. Several other things happened also, but they cannot be put down here.

‘I think I was right,’ said Strickland. ‘Now we will ask him to cure this case.’

But the leper only mewed. Strickland wrapped a towel round his hand and took the gun-barrels out of the fire. I put the half of the broken walking stick through the loop of fishing-line and buckled the leper comfortably to Strickland’s bedstead. I understood then how men and women and little children can endure to see a witch burnt alive; for the beast was moaning on the floor, and though the Silver Man had no face, you could see horrible feelings passing through the slab that took its place, exactly as waves of heat play across red-hot iron – gun-barrels for instance.

Strickland shaded his eyes with his hands for a moment and we got to work. This part is not to be printed.

* * * * *

The dawn was beginning to break when the leper spoke. His mewings had not been satisfactory up to that point. The beast had fainted from exhaustion and the house was very still. We unstrapped the leper and told him to take away the evil spirit. He crawled to the beast and laid his hand upon the left breast. That was all. Then he fell face down and whined, drawing in his breath as he did so.

We watched the face of the beast, and saw the soul of Fleete coming back into the eyes. Then a sweat broke out on the forehead and the eyes – they were human eyes – closed. We waited for an hour but Fleete still slept. We carried him to his room and bade the leper go, giving him the bedstead, and the sheet on the bedstead to cover his nakedness, the gloves and the towels with which we had touched him, and the whip that had been hooked round his body. He put the sheet about him and went out into the early morning without speaking or mewing.

Strickland wiped his face and sat down. A night-gong, far away in the city, made seven o’clock.

‘Exactly four-and-twenty hours!’ said Strickland. ‘And I’ve done enough to ensure my dismissal from the service, besides permanent quarters in a lunatic asylum. Do you believe that we are awake?’

The red-hot gun-barrel had fallen on the floor and was singeing the carpet. The smell was entirely real.

That morning at eleven we two together went to wake up Fleete. We looked and saw that the black leopard-rosette on his chest had disappeared. He was very drowsy and tired, but as soon as he saw us, he said, ‘Oh! Confound you fellows. Happy New Year to you. Never mix your liquors. I’m nearly dead.’

‘Thanks for your kindness, but you’re over time,’ said Strickland. ‘To-day is the morning of the second. You’ve slept the clock round with a vengeance.’

The door opened, and little Dumoise put his head in. He had come on foot, and fancied that we were laying out Fleete.

‘I’ve brought a nurse,’ said Dumoise. ‘I suppose that she can come in for… what is necessary.’

‘By all means,’ said Fleete cheerily, sitting up in bed. ‘Bring on your nurses.’

Dumoise was dumb. Strickland led him out and explained that there must have been a mistake in the diagnosis. Dumoise remained dumb and left the house hastily. He considered that his professional reputation had been injured, and was inclined to make a personal matter of the recovery. Strickland went out too. When he came back, he said that he had been to call on the Temple of Hanuman to offer redress for the pollution of the god, and had been solemnly assured that no white man had ever touched the idol and that he was an incarnation of all the virtues labouring under a delusion.

‘What do you think?’ said Strickland.

I said, ‘There are more things…’

But Strickland hates that quotation. He says that I have worn it threadbare.

One other curious thing happened which frightened me as much as anything in all the night’s work. When Fleete was dressed he came into the dining-room and sniffed. He had a quaint trick of moving his nose when he sniffed. ‘Horrid doggy smell, here,’ said he. ‘You should really keep those terriers of yours in better order. Try sulphur, Strick.’

But Strickland did not answer. He caught hold of the back of a chair, and, without warning, went into an amazing fit of hysterics. It is terrible to see a strong man overtaken with hysteria. Then it struck me that we had fought for Fleete’s soul with the Silver Man in that room, and had disgraced ourselves as Englishmen for ever, and I laughed and gasped and gurgled just as shamefully as Strickland, while Fleete thought that we had both gone mad. We never told him what we had done.

Some years later, when Strickland had married and was a church-going member of society for his wife’s sake, we reviewed the incident dispassionately, and Strickland suggested that I should put it before the public.

I cannot myself see that this step is likely to clear up the mystery; because, in the first place, no one will believe a rather unpleasant story, and, in the second, it is well known to every right-minded man that the gods of the heathen are stone and brass, and any attempt to deal with them otherwise is justly condemned.

IN KROPFSBERG KEEP (1895)

Ralph Adams Cram (1863–1942)

Ralph Adams Cram’s main claim to fame is as an architect. Born in New Hampshire, he became one of America’s leading designers of buildings in the Gothic Revival style. His churches can be found all over the USA from New York and Boston to Denver and Houston. Most of his published writings were on the subject of architecture but, as a young man, he wrote some fiction. Black Spirits and White, first published in 1895, was a collection of ghost stories, many of which drew on his memories of travelling in Europe to study architecture. ‘The Dead Valley’, one of the stories in this volume, is about two twelve-year-old boys in rural Sweden who journey to the next village from theirs and blunder into the terrifying landscape which provides the tale with its title. It is a minor classic of supernatural fiction and was described by H. P. Lovecraft as achieving ‘a memorably potent degree of vague regional horror’. Most of the other stories describe the experiences of the narrator and his friend Tom Rendel (clearly based on Cram himself and his friend Thomas Randall) as they traipse around Europe in search of the Gothic. ‘In Kropfsberg Keep’ purports to be a story they heard in the Tyrol and features two other young men who, with fatal consequences, take it upon themselves to investigate the ghosts reputed to haunt a ruined castle.

To the traveller from Innsbrück to Munich, up the lovely valley of the silver Inn, many castles appear, one after another, each on its beetling cliff or gentle hill – appear and disappear, melting into the dark fir trees that grow so thickly on every side – Laneck, Lichtwer, Ratholtz, Tratzberg, Matzen, Kropfsberg, gathering close around the entrance to the dark and wonderful Zillerthal.

But to us – Tom Rendel and myself – there are two castles only: not the gorgeous and princely Ambras, nor the noble old Tratzberg, with its crowded treasures of solemn and splendid mediævalism; but little Matzen, where eager hospitality forms the new life of a never-dead chivalry, and Kropfsberg, ruined, tottering, blasted by fire and smitten with grievous years – a dead thing, and haunted – full of strange legends, and eloquent of mystery and tragedy.

We were visiting the von C—s at Matzen, and gaining our first wondering knowledge of the courtly, cordial castle life in the Tyrol – of the gentle and delicate hospitality of noble Austrians. Brixleg had ceased to be but a mark on a map, and had become a place of rest and delight, a home for homeless wanderers on the face of Europe, while Schloss Matzen was a synonym for all that was gracious and kindly and beautiful in life. The days moved on in a golden round of riding and driving and shooting: down to Landl and Thiersee for chamois, across the river to the magic Achensee, up the Zillerthal, across the Schmerner Joch, even to the railway station at Steinach. And in the evenings after the late dinners in the upper hall where the sleepy hounds leaned against our chairs looking at us with suppliant eyes, in the evenings when the fire was dying away in the hooded fireplace in the library, stories. Stories, and legends, and fairy tales, while the stiff old portraits changed countenance constantly under the flickering firelight, and the sound of the drifting Inn came softly across the meadows far below.

If ever I tell the story of Schloss Matzen, then will be the time to paint the too inadequate picture of this fair oasis in the desert of travel and tourists and hotels; but just now it is Kropfsberg the Silent that is of greater importance, for it was only in Matzen that the story was told by Fräulein E— the gold-haired niece of Frau von C— one hot evening in July, when we were sitting in the great west window of the drawing-room after a long ride up the Stallenthal. All the windows were open to catch the faint wind, and we had sat for a long time watching the Otzethaler Alps turn rose-colour over distant Innsbrück, then deepen to violet as the sun went down and the white mists rose slowly until Lichtwer and Laneck and Kropfsberg rose like craggy islands in a silver sea.

And this is the story as Fräulein E— told it to us – the Story of Kropfsberg Keep.

* * * * *

A great many years ago, soon after my grandfather died, and Matzen came to us, when I was a little girl, and so young that I remember nothing of the affair except as something dreadful that frightened me very much, two young men who had studied painting with my grandfather came down to Brixleg from Munich, partly to paint, and partly to amuse themselves – ‘ghost-hunting’ as they said, for they were very sensible young men and prided themselves on it, laughing at all kinds of ‘superstition’, and particularly at that form which believed in ghosts and feared them. They had never seen a real ghost, you know, and they belonged to a certain set of people who believed nothing they had not seen themselves – which always seemed to me very conceited. Well, they knew that we had lots of beautiful castles here in the ‘lower valley’, and they assumed, and rightly, that every castle has at least one ghost story connected with it, so they chose this as their hunting ground, only the game they sought was ghosts, not chamois. Their plan was to visit every place that was supposed to be haunted, and to meet every reputed ghost, and prove that it really was no ghost at all.

There was a little inn down in the village then, kept by an old man named Peter Rosskopf, and the two young men made this their headquarters. The very first night they began to draw from the old innkeeper all that he knew of legends and ghost stories connected with Brixleg and its castles, and as he was a most garrulous old gentleman he filled them with the wildest delight by his stories of the ghosts of the castles about the mouth of the Zillerthal. Of course the old man believed every word he said, and you can imagine his horror and amazement when, after telling his guests the particularly blood-curdling story of Kropfsberg and its haunted keep, the elder of the two boys, whose surname I have forgotten, but whose Christian name was Rupert, calmly said, ‘Your story is most satisfactory: we will sleep in Kropfsberg Keep to-morrow night, and you must provide us with all that we may need to make ourselves comfortable.’

The old man nearly fell into the fire. ‘What for a blockhead are you?’ he cried, with big eyes. ‘The keep is haunted by Count Albert’s ghost, I tell you!’

‘That is why we are going there to-morrow night; we wish to make the acquaintance of Count Albert.’

‘But there was a man stayed there once, and in the morning he was dead.’

‘Very silly of him; there are two of us, and we carry revolvers.’

‘But it’s a ghost, I tell you,’ almost screamed the innkeeper; ‘are ghosts afraid of firearms?’

‘Whether they are or not, we are not afraid of them.’

Here the younger boy broke in – he was named Otto von Kleist. I remember the name, for I had a music teacher once by that name. He abused the poor old man shamefully; told him that they were going to spend the night in Kropfsberg in spite of Count Albert and Peter Rosskopf, and that he might as well make the most of it and earn his money with cheerfulness.

In a word, they finally bullied the old fellow into submission, and when the morning came he set about preparing for the suicide, as he considered it, with sighs and mutterings and ominous shakings of the head.

You know the condition of the castle now – nothing but scorched walls and crumbling piles of fallen masonry. Well, at the time I tell you of, the keep was still partially preserved. It was finally burned out only a few years ago by some wicked boys who came over from Jenbach to have a good time. But when the ghost hunters came, though the two lower floors had fallen into the crypt, the third floor remained. The peasants said it could not fall, but that it would stay until the Day of Judgment, because it was in the room above that the wicked Count Albert sat watching the flames destroy the great castle and his imprisoned guests, and where he finally hung himself in a suit of armour that had belonged to his mediæval ancestor, the first Count Kropfsberg.

No one dared touch him, and so he hung there for twelve years, and all the time venturesome boys and daring men used to creep up the turret steps and stare awfully through the chinks in the door at that ghostly mass of steel that held within itself the body of a murderer and suicide, slowly returning to the dust from which it was made. Finally it disappeared, none knew whither, and for another dozen years the room stood empty but for the old furniture and the rotting hangings.

So, when the two men climbed the stairway to the haunted room, they found a very different state of things from what exists now. The room was absolutely as it was left the night Count Albert burned the castle, except that all trace of the suspended suit of armour and its ghastly contents had vanished.

No one had dared to cross the threshold, and I suppose that for forty years no living thing had entered that dreadful room.

On one side stood a vast canopied bed of black wood, the damask hangings of which were covered with mould and mildew. All the clothing of the bed was in perfect order, and on it lay a book, open, and face downward. The only other furniture in the room consisted of several old chairs, a carved oak chest, and a big inlaid table covered with books and papers, and on one corner two or three bottles with dark solid sediment at the bottom, and a glass, also dark with the dregs of wine that had been poured out almost half a century before. The tapestry on the walls was green with mould, but hardly torn or otherwise defaced, for although the heavy dust of forty years lay on everything the room had been preserved from further harm. No spider web was to be seen, no trace of nibbling mice, not even a dead moth or fly on the sills of the diamond-paned windows; life seemed to have shunned the room utterly and finally.

The men looked at the room curiously, and, I am sure, not without some feelings of awe and unacknowledged fear; but, whatever they may have felt of instinctive shrinking, they said nothing, and quickly set to work to make the room passably inhabitable. They decided to touch nothing that had not absolutely to be changed, and therefore they made for themselves a bed in one corner with the mattress and linen from the inn. In the great fireplace they piled a lot of wood on the caked ashes of a fire dead for forty years, turned the old chest into a table, and laid out on it all their arrangements for the evening’s amusement: food, two or three bottles of wine, pipes and tobacco, and the chess-board that was their inseparable travelling companion.

All this they did themselves: the innkeeper would not even come within the walls of the outer court; he insisted that he had washed his hands of the whole affair, the silly dunderheads might go to their death their own way. He would not aid and abet them. One of the stable boys brought the basket of food and the wood and the bed up the winding stone stairs, to be sure, but neither money nor prayers nor threats would bring him within the walls of the accursed place, and he stared fearfully at the hare-brained boys as they worked around the dead old room preparing for the night that was coming so fast.

At length everything was in readiness, and after a final visit to the inn for dinner Rupert and Otto started at sunset for the Keep. Half the village went with them, for Peter Rosskopf had babbled the whole story to an open-mouthed crowd of wondering men and women, and as to an execution the awe-struck crowd followed the two boys dumbly, curious to see if they surely would put their plan into execution. But none went farther than the outer doorway of the stairs, for it was already growing twilight. In absolute silence they watched the two foolhardy youths with their lives in their hands enter the terrible Keep, standing like a tower in the midst of the piles of stones that had once formed walls joining it with the mass of the castle beyond. When a moment later a light showed itself in the high windows above, they sighed resignedly and went their ways, to wait stolidly until morning should come and prove the truth of their fears and warnings.